Unit 2 Beneficial Entitlement and Charity

Capital–Income Chart

Beneficiaries’ Entitlements

A beneficiary’s interest under a trust can be unconditional or conditional.

Understanding the nature of a beneficiary’s interest clarifies when they can call for trust property and what exactly they receive.

Capital vs. Income

Capital: The underlying value of the asset (e.g., market value).

Income: A regular monetary return (rent, dividends, interest).

Property | Capital | Income |

|---|---|---|

House | Market value of the house | Rent (if let) |

Shares | Market value of the shares | Dividends |

Bonds | Market value of the bond | Coupon payments (interest) |

Bank account | The account balance | Interest (if any) |

Antique desk | Market value of the antique desk | N/A (no ongoing income stream) |

A beneficiary entitled to capital typically has an absolute interest.

A beneficiary entitled only to income (e.g., rent or dividends) is said to have a limited interest.

Practical Implications

Trusts can provide for one beneficiary to receive only income and another to receive capital (e.g., life interest trusts).

Whether a beneficiary can demand early transfer of the trust property depends on the trust terms and the type of interest (capital or income).

1. Fixed Interest Trusts: General Overview

Definition: In a fixed interest trust, the settlor specifies in advance who will receive the trust property and when.

The settlor can decide, for example:

Whether a beneficiary must meet a condition (e.g., reaching a certain age) before becoming entitled.

Whether a beneficiary is entitled to capital, income, or both.

Thus, the interests of beneficiaries under a fixed interest trust are predetermined, leaving no discretion to the trustees regarding who gets what or how much.

2. Vested Interests

2.1 Definition

A vested interest is one where:

The beneficiary already exists, and

There are no conditions the beneficiary needs to fulfill before being entitled to the trust property.

In other words, the beneficiary’s interest is unconditional—they have an immediate right to the capital or income (or both), even if they have not yet taken possession.

2.2 Effect of Death Before Distribution

If a beneficiary with a vested interest dies before the trust property is actually transferred to them, that property passes to the beneficiary’s estate (under the beneficiary’s will or intestacy).

The interest does not revert to the settlor (unless the trust instrument says otherwise).

2.3 Example: Vested “Absolute” Interest

“I give my shares in Aviva plc to my Trustees to hold on trust for my son, Warren.”

Analysis:

Warren does not need to fulfill any condition (e.g., turning 25).

He has a vested interest in both capital (the shares themselves) and income (any dividends).

If Warren dies before receiving the shares, they go to his estate.

2.4 Minor Beneficiary

If the beneficiary is under 18, legal title cannot generally be transferred to them yet. The trustees must hold the property until the beneficiary reaches 18 (when they can give “good receipt”).

The interest, however, is still vested; the beneficiary just can’t take legal ownership until majority.

If the minor beneficiary dies before 18, the property goes to their estate.

2.5 Bare Trust on or After 18

Even after the beneficiary reaches 18, the trust doesn’t automatically end.

The beneficiary can request the property at any time after turning 18.

Until the beneficiary demands it, the trustees hold it on a bare trust, giving the beneficiary an absolute right to call for the assets.

3. Contingent Interests

3.1 Definition

A contingent interest is conditional on some future event that may or may not happen.

Examples of conditions include:

Attaining a certain age (e.g., 21, 25),

Surviving someone else,

Or even the future existence of a certain category of beneficiaries (e.g., grandchildren not yet born).

3.2 Vesting Upon Satisfying the Condition

Once the beneficiary meets the condition (e.g., turns 25), the interest becomes vested.

If the beneficiary dies before the condition is satisfied, the interest fails—unless the settlor has made alternative provisions.

3.3 Example: Age Condition with Gift Over

“I give my shares in Aviva plc to my Trustees to hold on trust for my son, Warren, if he attains the age of 25 years, but if not to Cancer Research UK.”

Analysis:

Warren’s interest is contingent because he must reach age 25.

If Warren achieves 25 and then dies before actual transfer, his interest is vested at that point, so it passes to his estate.

If Warren dies before 25, the interest fails, and the property goes to Cancer Research UK.

3.4 Fixed Interest but Conditional

Even though the interest is contingent, this trust is still “fixed” because the settlor predetermines who gets the property (Warren, or else Cancer Research UK). The trustees have no discretion in deciding who should benefit.

4. Successive Interests (Life Interest Trusts)

4.1 Definition

Successive interests allow the trust property to be enjoyed by different beneficiaries in turn, often across generations.

A common arrangement is a life interest to one person, with remainder to another.

4.2 Example: Life Tenant and Remainderman

“I give my shares in Aviva plc to my Trustees to hold on trust for my wife, Yara, for life, remainder to my son, Adam.”

Analysis:

Yara (the life tenant) has a vested, limited interest in income from the shares during her lifetime.

Adam (the remainderman) has a vested interest in the capital (the shares themselves), but it is postponed until Yara’s death.

Life Tenant’s Rights

Entitled to all income generated by the trust property during their lifetime.

If real property is in the trust, the life tenant may live in it rent-free (the “use and enjoyment”).

Remainderman’s Rights

Adam’s interest is vested now, but he cannot take possession until Yara’s death.

Yara’s death is a certainty, so Adam’s interest is not contingent on an event that might never happen (unlike an age condition).

If Adam dies before Yara, his vested interest passes to his estate.

4.3 Conditional Remainders

The settlor can make the remainder interest contingent (e.g., “to my wife, Yara, for life, then to my son, Adam, if he reaches 25”).

If Adam dies at 24, his interest fails, and the property returns to the settlor (or passes to whoever the trust instrument specifies).

4.4 “Life Interest Trust” Nomenclature

When the trustee has to split income to one person and hold capital for another, we often call it a life interest trust.

It remains a fixed trust because the settlor has explicitly stated who gets the income and who gets the remainder.

5. Practical Takeaways

Vested Interest:

Unconditional, immediate entitlement (though actual possession might be deferred if the beneficiary is a minor).

Passes to the beneficiary’s estate if they die before receiving the property.

Contingent Interest:

Dependent on an event (e.g., reaching a certain age).

Fails if the event doesn’t happen; the property goes elsewhere (back to the settlor or another named beneficiary).

Successive Interests:

The settlor can create life interests (income for life) and remainders (capital after the life tenant’s death).

A remainderman’s interest can be either vested or contingent, depending on whether any further condition is imposed.

Discretionary Trusts

Definition and Key Feature

In a discretionary trust, the settlor defines a class of potential beneficiaries (the “objects”).

Trustees then decide who among that class receives how much (and when).

Until the trustees make a distribution, no individual object has a proprietary interest in the trust property; they only have a hope or expectation.

Objects vs. Beneficiaries

Objects: Individuals who could benefit, but who do not yet have a fixed entitlement.

Beneficiaries: Once the trustees exercise discretion in favor of a particular person, that individual becomes a beneficiary with a vested right to the portion allocated.

Example

“I give the money in my Barclays Bank plc current account to my Trustees to hold on trust for such of my children and in such shares as they in their discretion see fit.”

Children: Charles, Danielle, Eduard.

Until trustees decide, each child is an object—no one has a guaranteed share.

If trustees award all the money to Danielle, she obtains a vested right in that sum (assuming she’s over 18). Charles and Eduard get nothing.

Combining Fixed and Discretionary Elements

A trust can blend both approaches.

Example: “I give my shares in Kingfisher plc to my Trustees to hold on trust for my wife, Francesca, for life, remainder to such of my children as survive my wife and in such shares as my Trustees in their discretion see fit.”

Francesca: Vested life interest in the income (dividends).

Children: No current entitlement (not fixed or contingent) because they must be selected by the trustees after Francesca’s death. Thus, they are objects of the discretionary remainder trust.

Key Takeaways

In a pure discretionary trust, no object has an enforceable right to a portion until the trustees make a decision.

Hybrid Trusts can give one beneficiary a fixed entitlement (e.g., a life tenant), with a discretionary trust remainder for others.

Saunders v Vautier

1. Overview of the Rule

The rule in Saunders v Vautier states that if all beneficiaries who are absolutely entitled (i.e., they collectively own the entire beneficial interest in the trust) are adults (over 18) and mentally capable, they can demand that the trustees:

Transfer the trust property to them (or as they direct), and

Bring the trust to an end, even if the trust deed says it should continue longer.

2. The Basic Principle for a Sole Beneficiary

Bare Trust

A bare trust arises where there is a sole adult beneficiary with mental capacity and a vested interest in all the trust property.

The beneficiary can terminate the trust at any time and instruct the trustees to hand over the property.

Example:

Warren is the sole beneficiary of a trust once he has satisfied any condition (e.g., turning 25) and is over 18. The trust then becomes a bare trust, allowing him to call for the property immediately.

Rationale

This approach reflects the idea that the beneficiary owns the equitable interest; the trust property ultimately belongs to them. Restricting them from taking legal title would be illogical.

3. Extension to Multiple Beneficiaries

The rule in Saunders v Vautier applies even when there is more than one beneficiary, provided all beneficiaries who could possibly benefit:

Exist and are ascertained,

Are each 18 or over and mentally capable, and

Unanimously agree to end the trust.

If they meet these criteria and collectively hold absolute entitlement to the trust fund, the trustees must comply with their instructions—even if doing so overrides the settlor’s original plan.

3.1 “Absolutely Entitled” Explained

“Absolutely entitled” means there is no other person who could potentially gain a share in the trust fund.

If someone else might still become a beneficiary (e.g., unborn descendants, or reversionary interests not yet determined), that person’s interest must also be accounted for.

4. Illustrative Examples

4.1 Example (a) – Children with a Condition

“I give my estate to my Trustees to hold on trust for such of my children now living as reach the age of 21 years and, if more than one, in equal shares.”

Children: Gregory (24), Harriet (22), Iain (20).

Gregory and Harriet’s interests are vested (they both reached 21).

Iain’s interest is contingent (he’s 20, hasn’t yet reached 21).

But if Iain died tomorrow, his share would vest in Gregory and Harriet.

Conclusion:

Between them, Gregory, Harriet, and Iain own the whole beneficial interest; no one else can claim the estate.

All three are over 18, in existence, and presumably have mental capacity.

If they agree, they can end the trust immediately and compel a distribution.

4.2 Example (b) – Life Tenant and Remainderman

“I give my estate to my Trustees to hold on trust for my husband, Jack, for life, remainder to my daughter, Katherine.”

Jack (life tenant) and Katherine (remainderman) both have vested interests.

No other potential beneficiary.

If both are over 18 and mentally capable:

They can jointly direct the trustees to end the trust and split the property however they choose.

4.3 Example (c) – Contingent Interest + Potential Resulting Trust

“Nicola gave £300,000 to trustees for her cousin, Matt, if he reaches 30. Nicola died intestate; her next-of-kin is Oliver.”

Matt is currently 25, so his interest is contingent (condition: reaching 30).

If Matt dies before 30, his interest fails; the money reverts to Nicola’s estate—i.e., goes to Oliver (the intestate heir).

Therefore, both Matt and Oliver (the potential reversionary beneficiary) collectively hold the entire beneficial interest.

If they both agree, they can end the trust.

Oliver might demand a portion in exchange for his consent (e.g., a 50-50 split now).

Key Point

Beneficiaries can effectively override the settlor’s intentions through their agreement. If all persons entitled (in various scenarios) unite, the trustees must honor that agreement.

5. When the Rule Does Not Apply

If the class of beneficiaries is still open (e.g., includes future children or unborn persons), or if there’s another potential interest that hasn’t been ascertained, the rule can’t be invoked unless that potential interest-holder also joins in.

Example:

“I give my estate to my Trustees to hold on trust for such of my children who reach the age of 25.”

If all children are 18+ but none are yet 25, they might not be absolutely entitled because if they all died under 25, the property would revert to the settlor’s estate. The settlor (or their estate) is also a “potential interest-holder.”

6. Practical Implications

Terminating a Trust Early

The rule allows beneficiaries to collapse the trust if they meet the Saunders v Vautier criteria.

Planning and Drafting

Sometimes settlors try to structure trusts to prevent an early wind-up by, for example, creating discretionary powers or multiple contingent interests.

Consent and Negotiations

Parties with potential interests may negotiate partial distributions before the trust’s intended termination date.

A Trust Terminates under Saunders v Vautier if ALL Beneficiaries...

Are in Existence and Ascertained

No potential or unborn beneficiaries remain.

Are Over 18 and Mentally Capable

All are legally competent (of full age and sound mind).

Unanimously Agree

They collectively decide to bring the trust to an end (or to direct the trustees to distribute in a particular way).

Charitable and Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts

Purpose Trusts vs. Trusts for Individuals

1. Overview of Purpose Trusts

A purpose trust is an express trust intended to carry out a specific purpose or objective (e.g., promoting good citizenship), rather than directly distributing property to named or identifiable individuals.

This type of trust faces special validity rules not typically encountered with trusts created for individuals:

The Beneficiary Principle: Generally, there must be identifiable beneficiaries who can enforce the trust.

Rule Against Perpetuities / Inalienability of Capital: Trust property should not be tied up forever without the possibility of eventual distribution.

2. Contrasting Trusts for Individuals

In fixed interest or discretionary trusts, trustees are ultimately obligated to distribute the trust property to specified people (whether fixed shares or at the trustees’ discretion).

Such trusts ordinarily do not raise the same problems as purpose trusts because:

Identifiable beneficiaries exist from the outset (even if they are a class of people).

The trust property is eventually alienable to those beneficiaries.

3. Identifying Purpose vs. Individuals Trust

Trust for Individuals:

The trust instrument instructs distribution directly to certain persons or a class of persons (e.g., “to such residents of Bath and in such shares as the trustees see fit”).

The ultimate duty is to hand over trust property to those individuals.

Purpose Trust:

The trust instrument primarily instructs the trustees to advance a goal or carry out a purpose, rather than pay out the property to specified beneficiaries (e.g., “to promote good citizenship”).

Persons mentioned in the trust deed may be targets or beneficiaries of the purpose, but they do not simply receive direct financial entitlements in the same way as beneficiaries under a traditional trust.

Examples

Trust for Individuals

“I give £400,000 on trust to my Trustees for such residents of Bath and in such shares as my Trustees think fit.”

While a letter of wishes suggests awarding funds to certain well-recognized citizens, the legal structure still provides that individuals ultimately receive the property.

Purpose Trust

“I give £400,000 on trust to my Trustees to promote good citizenship.”

The trustees’ role is to advance the cause of “good citizenship,” rather than distribute money directly to identifiable individuals.

Purpose Trust (with named people as the audience)

“I give £400,000 on trust to my Trustees to promote good citizenship amongst my relatives.”

Even though “relatives” are referenced, the trust’s purpose remains the promotion of good citizenship, not granting them a share of the fund outright.

4. Key Takeaways

Trusts for Individuals:

Ultimately pay money or property to the beneficiaries.

Usually avoid issues with the beneficiary principle and the rule against perpetuities.

Purpose Trusts:

Direct property toward an objective or aim.

Must navigate extra legal hurdles, notably:

Beneficiary principle: Who enforces the trust if no direct beneficiaries exist?

Rule against inalienability: Ensuring the trust property won’t be locked up indefinitely.

Can be charitable, which grants exemptions from these rules if they qualify.

By understanding these core distinctions, one can determine whether a given trust is valid and under what conditions it might fail or be enforced.

. Validity Rules for a Declaration of Trust (Recap)

When creating a purpose trust, the settlor must satisfy the general criteria for a valid express trust:

Certainty of Intention

Must be clear the settlor intended to create a trust and impose enforceable duties on the trustees.

Certainty of Subject-Matter

The trust assets (property subject to the trust) must be clearly identified.

Certainty of Objects

In a purpose trust, the “object” is actually the purpose to be carried out. Generally, that purpose must be sufficiently clear or specific so the trustees know how to apply the trust property.

(Charitable trusts are an exception; a vague statement of a charitable purpose can be refined or supervised by the Charity Commission.)

Beneficiary Principle

Normally, a valid trust must benefit identifiable beneficiaries who can enforce the trustees’ duties in court.

Purpose trusts potentially conflict with this principle because they do not specify individual beneficiaries.

Perpetuities

The law restricts tying up property in trust “too long” (the rule against perpetuities). For non-charitable purpose trusts, this translates into the rule against inalienability of capital (generally a 21-year limit).

Formalities

If the trust includes land, any declaration of trust must comply with s.53(1)(b), Law of Property Act 1925, meaning it should be evidenced in writing and signed by the person making the declaration.

2. The Beneficiary Principle and Purpose Trusts

2.1 General Rule: Trusts Must Have Enforceable Rights

Definition: The beneficiary principle provides that a trust is only valid if there are identifiable beneficiaries (persons) with a proprietary interest who can go to court to enforce the trust.

Reasoning:

Trust law relies on the concept that trustees owe fiduciary duties to beneficiaries.

If there is no beneficiary, there is nobody to ensure the trustees do their job properly.

The courts will typically not supervise or enforce a trust if no individual stands to benefit (except in specific exceptions, especially charitable trusts).

2.2 Impact on Purpose Trusts

Problem: A purpose trust directs trustees to carry out a purpose or objective rather than conferring direct entitlements on individuals.

Consequently, no private beneficiary can bring an action in court.

Hence, pure purpose trusts usually fail under the beneficiary principle—void for lack of an enforceable interest.

2.3 Example: Re Shaw 195719571957 1 WLR 51

Facts: George Bernard Shaw wanted a trust for researching a new 40-letter alphabet to see if it would save time.

Held: Trust was invalid. It benefited no individuals and thus offended the beneficiary principle. The court stressed, “A trust must be for the benefit of individuals... the court cannot control [or enforce] a trust for a mere purpose.”

3. The Rule Against Perpetuities (Rule Against Inalienability of Capital)

3.1 General Perpetuity Considerations

Trusts for Individuals:

Under modern perpetuity legislation, property can generally be held in trust for up to 125 years (the “perpetuity period”).

Purpose Trusts:

If the trust is non-charitable, the law is more restrictive.

A non-charitable purpose trust must not tie up (make inalienable) the capital for longer than 21 years, unless trustees have the power to spend it outright (thereby ending the trust).

This narrower limit is referred to as the “rule against inalienability of capital.”

3.2 Consequence for Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts

A non-charitable purpose trust violates the rule against inalienability if it:

Locks away the trust capital beyond 21 years, and

Offers no mechanism for the trustees to spend the capital so as to end the trust.

Exceptions: The trust can avoid perpetuity issues if:

The trust deed says it will last a maximum of 21 years (or “as long as the law allows”), or

Trustees can spend the entire capital immediately if they see fit, ending the trust at any time.

3.3 Examples of Inalienability Violations

Example (a)

“I give £40,000 to my Trustees so they may use the income to maintain the changing rooms at Beeston tennis club.”

The settlor wants to keep the capital intact so it continues generating income indefinitely (maintenance funded by dividends/interest).

The trust does not specify any end date within 21 years, implying the trustees keep capital locked in perpetuity.

Result: This fails the rule against inalienability. The trust is void.

Example (b)

“I give £40,000 to my Trustees so they may build changing rooms at Beeston tennis club.”

Trustees can spend the entire sum on constructing the facilities, which ends the trust once the capital is used up.

No perpetual lock-up of capital.

Result: This trust does not offend the inalienability rule and can be valid if it meets other requirements (e.g., the beneficiary principle, or qualifies as a valid purpose in another way).

4. Combining the Issues

4.1 Why Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts Usually Fail

Beneficiary Principle:

No direct human beneficiary = no one to enforce the trust.

Rule Against Inalienability:

If the trust tries to last beyond 21 years without an absolute spend-out power, it becomes void.

4.2 Charitable Purpose Trusts

Charitable Trusts are exempt from these problems if they meet the legal definition of “charitable.”

They do not fail the beneficiary principle because the Attorney General (or Charity Commission in England and Wales) can enforce the trust on behalf of the public interest.

They do not fail the inalienability rule because charity is deemed sufficiently beneficial to the public, and legislation allows charities to exist in perpetuity.

5. Key Takeaways

Purpose Trusts

Generally void if non-charitable, because they lack an enforceable beneficiary (beneficiary principle) and risk tying up capital indefinitely (rule against inalienability).

Exceptions

Charitable Trusts (meeting strict legal criteria) avoid these pitfalls.

Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts can be valid only if they fit recognized exceptions (e.g., certain “trusts of imperfect obligation”) or if the deed ensures compliance with the 21-year limit/spending power.

Practical Guidance

Drafters often ensure a purpose trust either:

Qualifies as charitable,

Includes a time limit (≤ 21 years),

Permits full expenditure of the capital, or

Satisfies another recognized exemption.

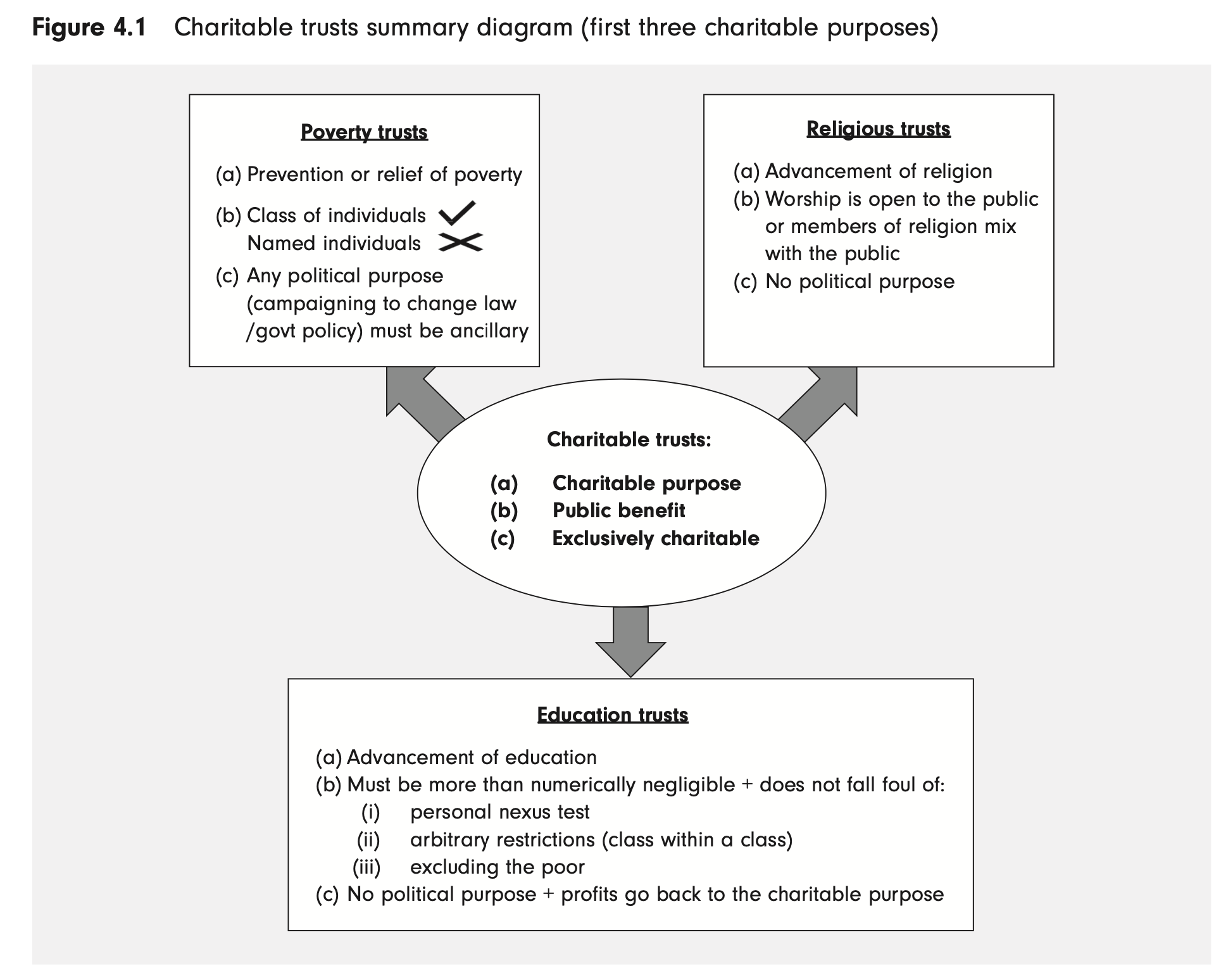

1. Overview of Charitable Trusts

Charitable trusts are a special type of purpose trust that do not fail for lack of human beneficiaries (beneficiary principle) and can last indefinitely without breaching the rule against perpetuities (rule against inalienability of capital). They are subject to distinct legal and regulatory requirements, primarily found in the Charities Act 2011 (CA 2011).

Key Benefits:

Exemption from the Beneficiary Principle: No private beneficiary is required; enforcement is via the Attorney General (on behalf of the public) or the Charity Commission.

Exemption from the Rule Against Inalienability: Charitable trusts can hold capital indefinitely in furtherance of their charitable objectives.

2. Legal Framework and Regulation

Attorney General and Charity Commission

Most charities are regulated by the Charity Commission for England and Wales.

The Attorney General can bring actions to enforce charitable trusts in court if necessary.

Registration and Status

To be recognized as a charity, a trust must meet three conditions under s.1–3 CA 2011:

The purpose must be charitable.

There must be sufficient public benefit.

The trust must be exclusively charitable (no non-charitable element).

3. Charitable Purposes

Section 3(1) CA 2011 lists 13 specific “heads” of charity. A trust must fall under at least one. Charitable trusts frequently combine more than one. Some key examples include:

Prevention or Relief of Poverty

“Poverty” does not mean absolute destitution but includes those who “go short” (Re Coulthurst 195119511951).

Trusts to aid unemployed, refugees, or victims of disasters can qualify.

Advancement of Education

Includes scholarships, constructing schools or universities, paying teachers or researchers, maintaining museums or libraries, and any useful research (provided results are published and disseminated).

Advancement of Religion

Must involve promoting or sustaining religious belief or worship (“a belief that there is more to be understood about mankind’s nature and relationship to the universe than can be gained from the senses or from science” – Hodkin v Registrar General 201320132013).

Supporting places of worship, religious publications, or services qualify.

(Additional heads exist, such as the advancement of health, the arts, amateur sports, environmental protection, etc. See CA 2011 for the full list.)

4. Public Benefit Requirement

All charitable trusts must show sufficient public benefit, which has two aspects:

Identifiable Benefit

The trust’s aim must be clearly beneficial rather than detrimental (a “school for pickpockets” would fail).

Benefit to the Public (or a “Sufficient Section” of It)

The potential beneficiaries cannot be a negligible or arbitrarily restricted group. What counts as sufficient depends on which charitable head applies.

Public Benefit: Basic Idea

For a trust to be charitable, it must benefit the public or at least a sufficiently large section of the public.

Sometimes, a trust says it will help only certain people (a “restricted group”). Then we must decide if that group is still big or broad enough to be considered “public” for charitable purposes, or if the group is too narrow.

Different Rules for Different Charitable Purposes

Prevention or Relief of Poverty

If a trust is specifically about reducing poverty, the law is very generous:

A trust cannot be set up to help only particular named individuals (e.g., “I give £10,000 to help John Smith and Jane Brown” is not charitable—that’s just two named individuals).

However, a trust to relieve poverty among “my family” is considered charitable, even if that might only help a few people in practice.

Why? Because society sees the prevention of poverty as extremely important, and helping any subset of people at risk of poverty is allowed.

Advancement of Religion

It’s enough that the place of worship is open to the public—even if only a few people actually attend.

Alternatively, if the place of worship isn’t open to all, the members must still “live in the world and mix with other citizens.”

If they are cloistered or completely separated from the outside world, they don’t fulfill public benefit (case: Gilmour v Coats).

Example: A small chapel that anyone can visit is okay (even if only ten people show up regularly). If the chapel were locked away and only accessible to a group who never interacts with society, the public benefit is missing.

Advancement of Education (and Other Purposes)

This is where the rules get more detailed. The trust must not be so restrictive that it benefits only a few specific people with no broader “public” dimension.

Key Tests When the Group is “Restricted”

The “Personal Nexus” Test

If the people who benefit are linked by a “personal nexus” (family relationship or employment to a single employer), the trust fails as not sufficiently “public.”

Example: “I give £250,000 for the education of the children of employees of Red Anchor Ltd.”

All the kids share a common link to one employer. This is too much like private benefit, so it’s not charitable (Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust 195119511951).

Even if Red Anchor Ltd has a thousand employees, it’s still not enough—everyone is connected by that private link (the company).

The “Class Within a Class” Test

A “class within a class” problem arises if you have two or more layers of restriction (for instance, you must (a) live in a certain place, and (b) belong to a certain religion).

If these restrictions are legitimate and rational—like geography for a local benefit—it might still be okay. But if the extra restriction is arbitrary, you could fail the public benefit.

Example: IRC v Baddeley 195519551955—the trust was for promoting sports among people in West Ham who were or might become Methodists.

“West Ham” alone could be acceptable (a geographic restriction).

But adding “Methodists only” was deemed arbitrary, because promoting sport is presumably helpful for everyone.

The group “Methodists in West Ham” is a “class within a class” that the court found unjustified.

Important: Having more than one restriction doesn’t automatically fail. You just need to ensure each restriction has a genuine reason connected to the trust’s purpose.

Must Not Exclude the Poor

A charitable institution can charge fees (like a private school or hospital), but it still has to show it serves more than just the wealthy.

Example: Independent Schools Council v Charity Commission 201220122012.

Fee-charging schools with charitable status must do enough to include or assist people who can’t afford high fees.

This might be scholarships, bursaries, or letting local state school kids use their facilities.

Simply saying, “We allow wealthy families to pay tuition,” is not enough for public benefit if you exclude all but the rich.

Examples Illustrating Public Benefit Restrictions

Trust for Education of Employees’ Children

“I give £250,000 to educate children of employees of Red Anchor Ltd.”

Fails the public benefit requirement due to the personal nexus (all connected by the same employer).

Promoting Sport for Methodists in West Ham

“I give £100,000 to promote sports among West Ham residents who are or become Methodists.”

Fails under IRC v Baddeley because it imposes an additional and arbitrary restriction (“Methodists only”). That’s a “class within a class.”

Fee-Charging School

If a private school charges high fees but provides scholarships or open access to some local pupils, it may retain charitable status because it isn’t excluding the poor.

If, however, no help is given to those who can’t pay, it would risk losing charitable status.

Trust to Relieve Poverty Among ‘My Family’

This passes the public benefit test (for the “relief of poverty” head). Even though it’s a small group, the courts allow it because preventing poverty is considered crucial.

5. Why Does Public Benefit Matter?

The law wants to make sure that a “charitable” trust is actually serving some segment of society at large—not just a disguised way of benefiting a private group (like an extended family or employees).

Where the trust is truly about helping or improving the welfare of a broad or important sector (like all local residents, or a recognized religious congregation), it’s charitable.

If it’s about giving special perks to a small, closed-off group with no broader purpose, it’s not charitable.

1. Exclusively Charitable: What Does It Mean?

A trust will qualify as a charity only if all of its purposes are charitable. If any part of its object or main purpose is non-charitable, the trust fails to qualify as charitable.

The Charities Act 2011 sets three conditions for charitable status:

Charitable Purpose (must fall under one of the heads in the Act, e.g., relief of poverty, advancement of education, etc.),

Public Benefit, and

Exclusively Charitable (i.e., no non-charitable elements).

2. Political Purposes: Not Permitted as a Main Aim

2.1 Definition of Political Purposes

A political purpose includes:

Supporting a political party, or

Campaigning for a change in the law, government policy, or decisions—whether in the UK or abroad.

Bodies that have a mixture of charitable and political purposes will not be given charitable status.

2.2 Example: McGovern v Attorney General 198219821982

Facts: Amnesty International sought charitable status for a trust that (among other things) aimed to:

Secure the release of prisoners of conscience,

Abolish torture or degrading treatment.

Held: Trust not charitable. Although some aims (like “relief of needy persons”) were charitable, the main push to change laws and policies (i.e., ban torture, release prisoners) was political.

2.3 Incidental Political Activities

A charity can do some political activities so long as it remains secondary or incidental to a truly charitable main purpose.

Example: Oxfam may lobby governments to address infrastructure needs that help eradicate poverty—but that lobbying remains incidental to Oxfam’s primary charitable purpose (relieving poverty). If the political campaigning took over as the core mission, it would jeopardize charitable status.

3. Profits Must Be Reinvested (No Private Distribution)

A charitable organization can charge fees for services (e.g., a private school or hospital) and even make a profit—but:

It must not exclude the poor (see the public benefit test).

All profits must be ploughed back into the charitable work rather than paid out to private owners or shareholders.

If the trust (or institution) is run as a commercial venture mainly to generate profits for individuals, it cannot be charitable.

4. Putting It All Together: Examples

4.1 Trust for Relieving Poverty Among “My Relatives”

“I give £50,000 to my Trustees to use the income to relieve poverty among my relatives.”

Purpose: Relief of poverty (a recognized charitable purpose under s.3(1), Charities Act 2011).

Public Benefit: Preventing or relieving poverty is considered so important that the law allows it even for a small group like “my relatives.” (If the trust listed specific named individuals, that would be different—mere gifts to specific people are not charitable.)

Exclusively Charitable: No political element, no private profit distribution beyond relieving poverty.

Outcome: This trust is charitable and can last forever without violating perpetuity rules.

4.2 Trust to Provide Educational Scholarships for “My Children”

“I give £400,000 to my Trustees to use the income to provide educational scholarships for my children.”

Purpose: Advancement of education (a charitable head).

Public Benefit: Fails the “public” part because the beneficiaries are only “my children,” a personal nexus. For education, a small family group is not regarded as “the public.”

Exclusively Charitable: Although the purpose (education) is charitable in principle, the lack of sufficient public benefit makes it fail overall as a charity.

4.3 Trust to Campaign for Welsh Independence

“I give £250,000 to my Trustees to campaign for Wales to become an independent sovereign state.”

Purpose: Changing the law or government policy.

Political: This is entirely a political aim (seeks constitutional/legal change).

Outcome: Not charitable because political aims are incompatible with exclusive charitable status.

1. Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts: Basic Issue

General Rule: Purpose trusts (trusts created to carry out a purpose rather than benefit specific individuals) typically fail because:

They breach the beneficiary principle (no identifiable humans can enforce them), and

They risk violating the rule against inalienability of capital (must not lock up capital indefinitely).

Exceptions:

Re Denley Trusts – If a purpose trust nonetheless confers a tangible, enforceable benefit on identifiable individuals, they can enforce the trust.

Trusts of Imperfect Obligation – Permitted for certain “sentimental” purposes (pets, graves, etc.), though they remain unenforceable in court.

2. Re Denley Trusts

2.1 Key Features

A trust is valid under Re Denley’s Trust Deed 196919691969 if it:

Identifies the People Who Benefit

Even though it’s expressed as a “purpose,” there are real individuals (a class or group) who will enjoy a tangible advantage from that purpose.

These beneficiaries can go to court to enforce the trust.

Purpose Must Be Clear and Tangible

The trust’s aim (e.g., building a gym, maintaining a recreation ground) should be specific enough so that it’s actually carried out.

Ascertainable Beneficiaries

The group of people who stand to benefit must be conceptually certain (capable of passing the “given postulant” test).

Must Not Offend the Rule Against Inalienability

The trust is limited to 21 years (or less), or trustees can spend all the capital on the purpose (so the trust isn’t locked forever).

2.2 Examples

Valid Re Denley Trust

“I give £500,000 on trust to build a gymnasium for employees of King International Ltd.”

Purpose: Building a gym (a one-off spend).

Beneficiaries: Employees are ascertainable.

Capital Not Locked: Trustees can spend all funds on construction at once → no perpetual lock-up.

Outcome: Valid.

Invalid Re Denley Trust

“I give £500,000 on trust to build and maintain a gym for employees of King International Ltd.”

The maintenance element forces the trustees to keep capital locked to generate ongoing funding.

If not limited to 21 years or without a full spend-out option, it violates the rule against inalienability of capital.

Outcome: Void.

3. Trusts of Imperfect Obligation

3.1 Definition

These are purpose trusts where nobody has standing to enforce them if trustees do nothing. Despite that, the law allows a narrow set of these “sentimental” trusts:

Care of specific animals (e.g., a favorite pet),

Maintenance of graves or tombs (e.g., paying for upkeep of a family plot).

3.2 Validity Rules

Still Must Comply with Rule Against Inalienability

Typically, wording like “for as long as the law allows” (i.e., 21 years) ensures the trust ends before perpetuity is breached.

Unenforceable in Court

If trustees ignore the purpose, no direct beneficiary can sue.

The trust is “valid but unenforceable”.

Practically, if trustees fail to use the money for the stated purpose, the property might revert (e.g., via resulting trust) to the settlor’s residuary estate.

3.3 Example

“I give £20,000 to my Trustees to hold on trust to maintain my horse, Max, for as long as the law allows.”

Purpose: Maintaining a specific animal.

Perpetuity Compliance: “For as long as the law allows” → effectively limited to 21 years.

Outcome: Valid (though nobody can force trustees to spend the funds on Max).

4. Key Takeaways

Re Denley Trusts

Enforceable because real people benefit.

Must have clear, tangible purpose + identifiable beneficiaries + conform to perpetuity limits.

Trusts of Imperfect Obligation

Valid but not enforceable by any beneficiary—purely a legal concession for certain personal or sentimental aims (pets, graves).

Also limited by 21 years or a full spend-out provision.

Avoiding Void Purpose Trusts

Either ensure your purpose qualifies under Re Denley (there are identifiable, enforceable beneficiaries),

Or keep it within strict categories of imperfect obligation, with a clear 21-year (max) or “spend-all” rule.

By meeting these strict guidelines, a non-charitable purpose trust can legally exist without failing the beneficiary principle or perpetuity rules.

Knowt

Knowt