1.2.6 Government intervention

Government intervention to deal with externalities

Negative exteranlities of production are when third parties are negatively impacted by the production of a good/service. E.g. Pollution resulting from a factory.

Negative externaliites of consumption are the third party spillover effects due to the consumption of a good/service (demerit goods). E.g. sugar, alcohol.

Taxation

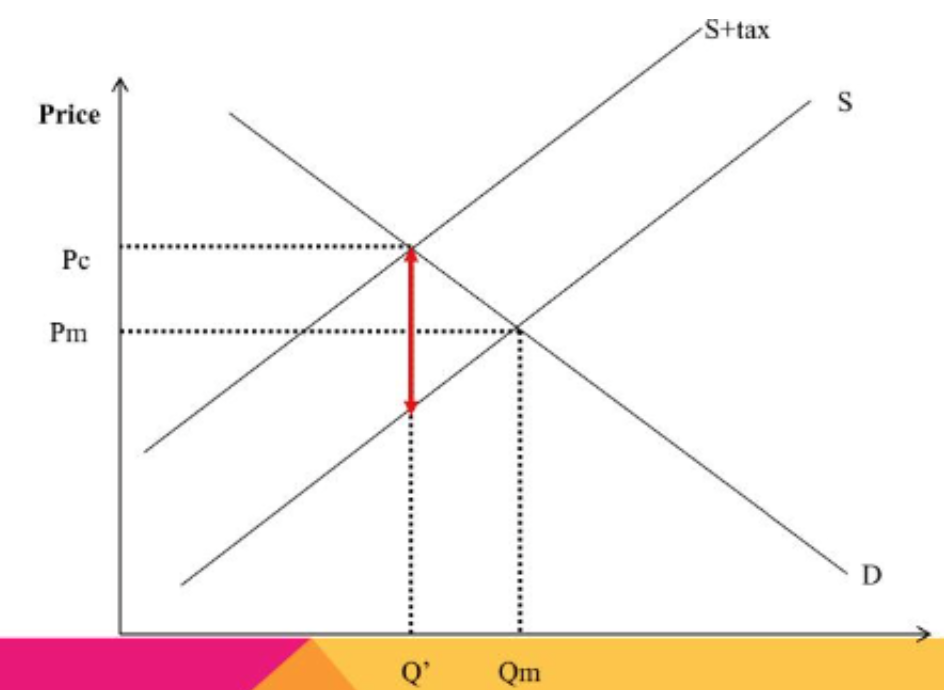

Indirect tax: The classic textbook solution to the problem of negative externalities is to use taxation. Imposing an indirect tax on a good or service causes its supply curve to shift to the left, because it causes the costs of the producer to rise. Although the producer may pass on some, or all, of the tax on to the consumer through higher prices (depending on the elasticity of the demand curve), it is the producer who actually pays the tax bill. A tax reduces supply. This means less is produced. This will reduce the negative externalities due to less production.

An indirect tax will also result in less demand (movement along demand curve) due to higher price.

Advantages of taxation:

Reduces negative externalities

Provides revenue for the government

Disadvantages of taxation:

Difficult for the government to use the correct level of tax.

If demand is inelastic, the tax will not decrease demand much

Taxes can cause inequality

Cost of administration – the cost of collecting taxes. E.g. employing people to contact firms to ensure they are paying the correct level of tax.

Possibility of evasion – firms may avoid of evade paying tax

Subsidies

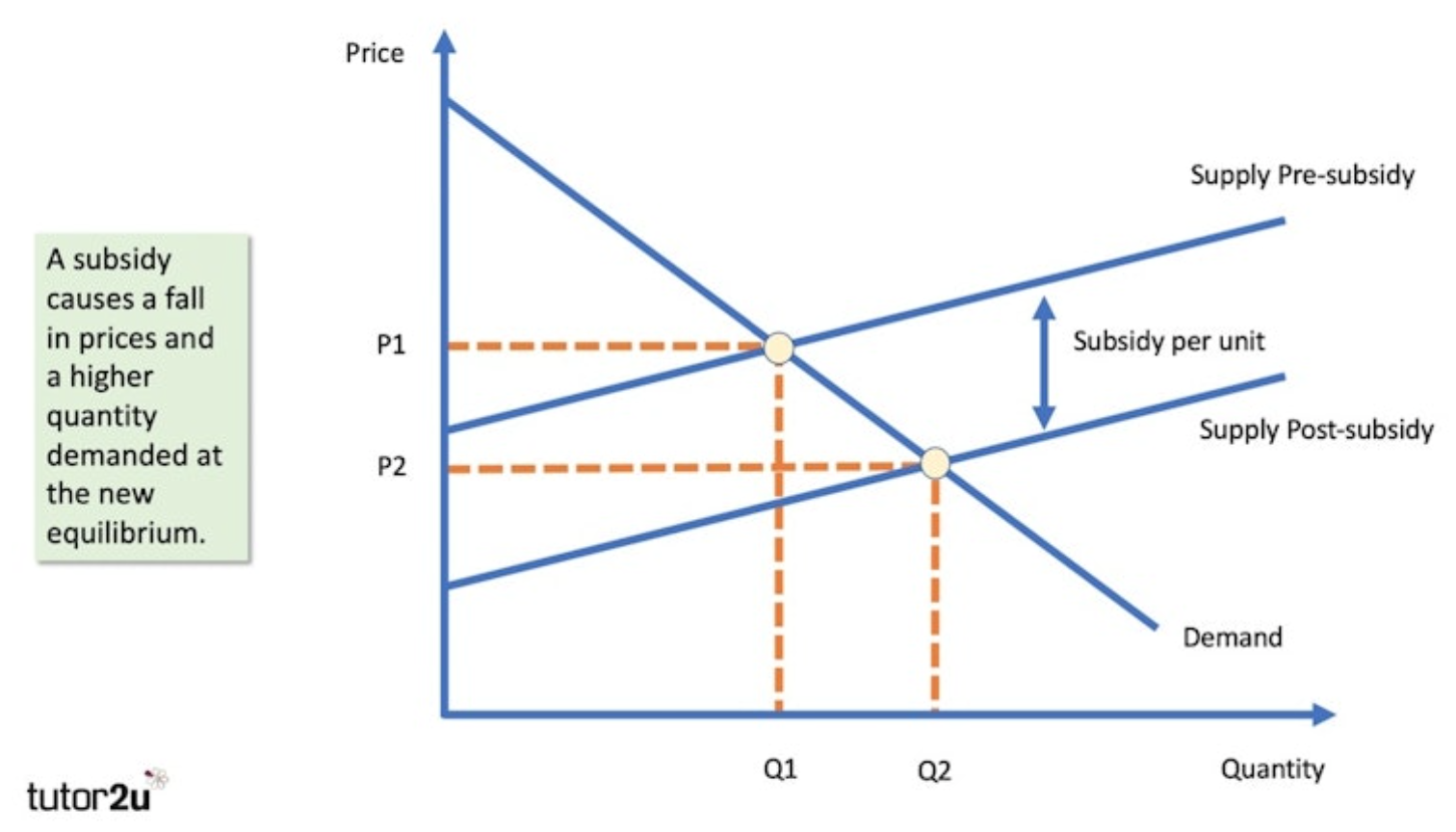

Subsidies are government payments to firms to increase production and/or reduce cost of production for firms. They can also increase consumption of a good or service.

Taxes shift a firm’s supply curve to the left, forcing them, via the market mechanism, to reduce output and increase the price to reflect the external cost. But what if the good in question has external benefits?

If you remember from above, education is an example of a good that has huge external benefits for society, so if it were left to the free market, output (which in this case means the number of people educated) would be lower than the socially optimal level.

In an effort to increase the output of these types of goods, the government can pay subsidies to the producers. This will cause the supply curve to shift to the right resulting in a higher output and lower prices. In fact, education in this country is free in the UK all children up to the age of 18. The subsidy is so big that the price is zero at the point of use.

Subsidies can also be used to reduce negative externalities of both consumption and production. E.g. if a ‘better’ alternative is subsidised (clean energy, healthy food etc.)

Advantages of subsidies

Can result in increased production/consumption of goods with positive externalities, benefiting society.

If you subsidise public transport, it will encourage people to drive less, and reduce their negative externalities. In the long term, subsidies for a good will help change preferences. It will encourage firms to develop more products with positive externalities.

Disadvantages of subsidies

The cost will have to be met through taxation. Some taxation, e.g. income tax, may reduce incentives to work. Though the most efficient way to raise revenue for subsidising positive externalities would be to tax goods with negative externalities, e.g. tax cars driving in city centres (congestion charge) and use the money to pay for public transport.

Difficult to estimate the extent of the positive externality. Therefore the government may have poor information about the service and how much to subsidise.

There is a danger that government subsidies may encourage firms to be inefficient and they come to rely on subsidy rather than improve efficiency.

The effect depends on the elasticity of demand. If demand is price elastic, a subsidy leads to large increase in demand. If demand is price inelastic, a subsidy is relatively ineffective in increasing demand.

Fines

Firms can be fined if they pollute too much or if they do not act in the consumer interest. E.g. if they form a cartel or collude. This is when firms will need to make a payment to the government. The amount of the fine will be decided by the government.

Advantages of fines

Can reduce negative externalities

Can increase government revenue

Disadvantages of fines

Depends on the level of the fine. Some firms may continue the behaviour and pay the fine if the fine is not big enough. If the fine is too much some firms may have to leave the market. Governments may not have enough information to set the fine at the correct level

If demand is inelastic, firms will simply pass the fine onto consumers in the form of higher prices.

Government regulation

Although in an ideal world the solution of ‘internalising the externalities’, which uses the market mechanism (taxing, subsidising or fining) would be perfect, in the real world, as we have discussed, it is difficult to get the tax/subsidy/fine level right. In some situations the government feels that their intervention needs to be a little more direct.

Instead of taxing pollution, why not just ban it? Or at least legislate to control pollution levels. For example, cars now have to do an emissions test before they are allowed to be sold.

Another example of regulation is planning permission. In some countries, firms have to get permission from the government before they build on land, or they cannot build above the tree level etc.

Advantages of regulation

Can help reduce negative externalities

Can have a direct impact on firm behaviour

Disadvantages of regulation

Depends on how severe the regulation is

It may be difficult to control firm behaviour. E.g. if firms do not comply with regulation, the government may have to fine the firms. A similar problem arises with the other types of government intervention (what is the right level of the fine)?

Pollution permits

Another more recent solution to the international problem of pollution is to issue permits which only allow each country world-wide a certain amount of emissions of, say, greenhouse gases. The sum of all the permits issued allows for a significant fall in world-wide emissions. Some countries will be better at reducing emissions than others. If the countries that are good at reducing emissions manage to keep their emissions below the level allowed by their permits, then they can sell their spare permits to countries that struggle to keep their emissions down.

Advantages of pollution permits

The key point is that the total level of emissions allowed world-wide is fixed by the sum of the permits, so emissions should fall. But this system is better than simply having ‘targets’ for lower pollution because the ‘cleaner’ countries have an incentive to reduce their emissions by more than they need to so that they can sell their spare permits and make some money.

In addition, the countries that have to buy the spare permits because they struggle to keep their emissions down will probably also have lower costs. The cost of purchasing the expensive equipment required to reduce emissions is probably higher than the cost of simply buying the extra permits.

Disadvantages of pollution permits

It is difficult to know how many permits to give out. The government may be too generous or too tight.

If firms buy more permits, they can just pass this extra cost onto consumers in the form of higher prices.

It can be difficult to measure pollution levels. There is potential for hiding pollution levels or shifting production to other countries, with looser environmental standards. In a globalised world, multinationals increasingly shift production around.

There are administration costs of implementing the scheme and measuring pollution levels.

For global pollution permits, countries who pollute more than their quotas can simply buy permits from other countries. Therefore rich developed countries can simply buy permits from less developed countries. This does not significantly reduce pollution but shifts it from the richer countries to poorer countries.

Environmentalists have argued a higher price of carbon is insufficient to reduce carbon dioxide to levels necessary to stop global warming. Demand for carbon permits is often price inelastic and too slow to act.

Government intervention to promote competition

Promoting competition

Encouraging the growth of small firms – Government can attempt to increase the number of small businesses in order to increase competition in the market. E.g. governments can give training and grants to potential new entrepreneurs. They can also give tax incentives or subsidise small firms.

Anti-competitive practices – These practices reduce competition in a market. E.g. firms can create a cartel (price fixing for contracts and allocate these contracts among themselves), firms may refuse to supply a customer unless the customer buys other products at a higher price, predatory pricing. These practices are illegal but difficult to prove. Additionally, if the fine for engaging in anti-competitive practices is less than the profit gained from such practices, there would be no incentive for the firm to stop.

Deregulation – can remove monopoly power and increase competition

Lowering barriers to entry – e.g. training and providing finance to firms

Privatisation – Privatisation with only increase competition when a nationalised monopoly is split up into competing firms or if barriers to entry are lowered to encourage new entrants.

Controlling monopolies

A monopoly can earn high profits at the expense of their customers. Therefore, it can be argued that governments should control monopolies. Methods include price controls, profit controls, performance targets, quality control, breaking up the monopolist, lowering entry barriers, windfall taxes, deregulation, subsidies and nationalization or privatisation.

Price controls – Monopolies can be forced to set a maximum price. Critics argue it is difficult for the government to know where the cost and revenue curves lie and therefore do not know where to set the maximum price. Price controls can also lead to dynamic inefficiency, e.g. investment in R&D may fall due to the fall in abnormal profits.

Profit controls – The government set a level of profit a monopoly can earn and excess profit is taxed 100%. However, it requires regulators to have a good understanding of costs and rates of return in the industry. The monopolist has incentive to inflate costs to show the regulators. Also, the monopolist has no incentive to minimise costs. If it is allowed to make a profit, it knows it has no incentive to minimise them. Monopolists may have an incentive to employ too much capital.

Quality standards – A profit maximising monopolist focuses on profit and not quality. Governments can set quality standards. E.g. in the UK, the Post Office has a legal obligation to deliver letters on a daily basis to rural areas despite the fact that deliveries to rural areas are loss making.

Performance targets – Price, quality and other targets can be put in place to regulate monopolies. Targets include degrees of customer choice, costs of production etc. Train companies are given a target based on the percentage of trains that arrive on time. Monopolies will try to play the system. E.g. Advertise train journeys as longer than they actually are. Monopolies may receive bad press or regulatory fines if they don’t meet performance targets. As with quality standards, it takes considerable political will and understanding of the industry. Performance targets will also have to be changed frequently.

Breaking-up the monopolist – The monopolist can be broken up into competing units by the government. This is designed to reduce monopoly power. In the case of natural monopolies, breaking up a monopolist would almost certainly lead to welfare losses.

Lowering entry barriers – E.g. deregulation. This is discussed below. Another example is providing finance. The government can subsidise small firms if the start-up costs are too high

Deregulation – the process of removing government controls from markets. E.g. allowing firms to enter state-run markets for example allowing private firms to deliver letters and parcels. Other regulations may be businesses having to apply for a licences etc. Deregulation increases efficiency in markets but it encourages ‘creaming’ of markets (firms only providing services in the most profitable areas – e.g. when bus companies were deregulated in the 1980s, bus firms only operated in urban areas where profit was high.)

Windfall taxes – These are taxes which are enforced after a monopolist has made large abnormal profits. These are imposed after the event has occurred. They tend to be arbitrary so are not a good long-term solution. Firms may end up artificially reducing their profits.

Privatisation and nationalisation – If the monopolist is state owned, it can be privatised. This means it is sold off to private sector owners. This can increase competition in the market, reduction monopoly power. Alternatively, monopolies can be nationalised. This is where the government takes ownership of private assets. A nationalised monopolist will work in the best interest of consumers and not shareholders. This may mean prices are reduced. The argument against nationalisation is that efficiency is lower due to less incentives to maximise profits and specialist management may not be a strong in the state sector.

Subsidies – One way of achieving allocative efficiency in a monopoly is my subsidising the firm. Subsidies would decrease MC, this will increase the profit maximising level of output. Firms can be subsidised until MC =P. The government can recoup the subsidy by taxing profits. It is difficult to know the correct level of subsidy to increase MC the right amount. It is also difficult to know where the allocative efficient level of output is.

Self-regulation – Firms establish their own standards or codes of practice. This can reduce the need of regulation by the government. Self-regulation tends to be weak in terms of influencing. E.g. Independent bodies set to investigate breaches of code will be staffed by workers employed by the firms that are being investigated.

Merger policy – Policy is in place to prevent the creation of mergers that will adversely affect a market.

Protect consumer interests

All legislation is aimed at protecting consumer interests. The government aim to control firms to lower prices and increase choice.

Controlling mergers

Mergers are investigated if they are too large. They can be prevented or fined. E.g. in the UK Firms involved in anti-competitive behaviour may find their agreements to be unenforceable and risk being fined up to 10% of group global turnover for particularly damaging behaviour. Furthermore, individuals could also find themselves facing director disqualification orders or even criminal sanctions for serious breaches of competition law.

Government intervention in the labour market

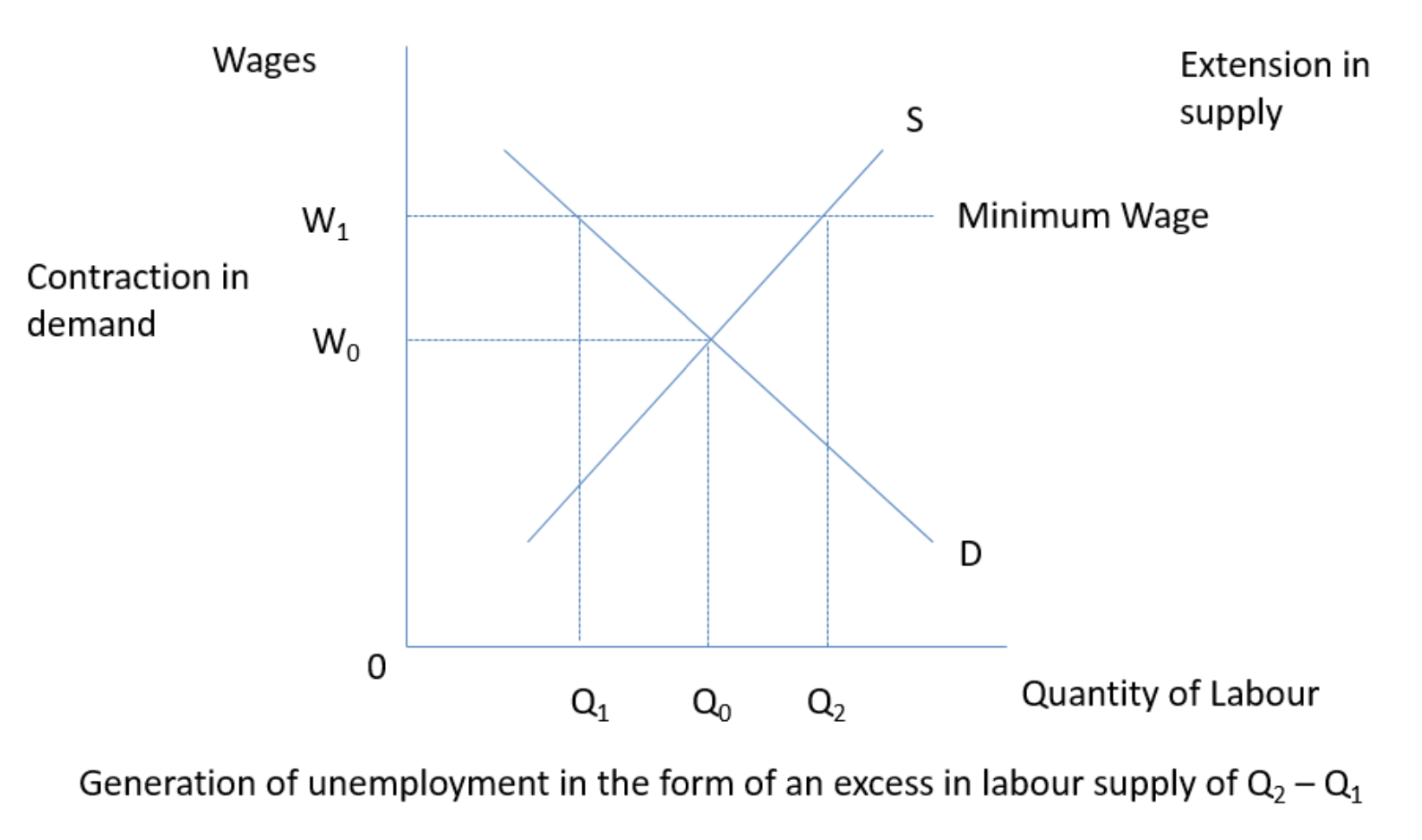

The minimum wage (National Minimum Wage NMW) is a legally enforced pay floor. Employers are not allowed to pay their employees a rate below the minimum wage. This only causes problems if the minimum wage set is above the equilibrium wage rate that would otherwise prevail in the labour market.

Note that if the minimum wage increases, the minimum wage line would shift up.

Employers cannot legally undercut the current minimum wage rate per hour (W1). This applies both to full-time and part-time workers.

The labour market equilibrium wage is Wo

If the minimum wage is set at W1, there will be an excess supply of labour equal to Q2 – Q1 because the supply of labour will expand (more workers will be willing and able to offer themselves for work at the higher wage than before) but there is a risk that the demand for workers from employers (businesses) will contract if the minimum wage is introduced.

This excess supply represents unemployment.

The minimum wage will only work if it is above the market equilibrium wage.

Advantages of the NMW

Reducing poverty. Unsurprisingly, households whose earners were paid less than the NMW also tended to be those who were officially defined as ‘in poverty’ (income of less than half median earnings). It was felt that the NMW would lift households out of poverty. Of course, this leads to another advantage of the NMW; it should, therefore, lead to a fairer distribution of income.

Tax and benefits. If earnings rise as a result of the NMW, government tax receipts from earners will rise and the benefits paid to those in work but on low incomes should reduce. Government finances will improve, which could be spent on reducing the national debt, reducing taxes or spending on important services like education or health.

The effect on productivity. Some economists believe that the increased wage might improve labour productivity. Workers may respond to their higher wage rate by working harder, possibly as a result of worrying about losing their job now that the increased wage rate has made it a more ‘sought after’ job. Employers may force through productivity improvements. They may feel that the increased wage rate needs to be earned through increased efforts!

Improved incentives. It may be difficult to believe, but there are a number of people who are voluntarily unemployed. They are not prepared to supply their labour services at the given equilibrium wage in the labour market that is appropriate to their skills. To put it in cruder terms, who would want to clean toilets for £2 an hour? Many would rather collect unemployment benefit and do nothing. A NMW puts a floor of these low wage rates and acts as an incentive to encourage some of these ‘voluntarily unemployed’ people back to work. This will save the government money on benefits, increase income tax revenues and improve the productive potential of the economy

Disadvantages of a Minimum Wage

Although all political parties are now committed to keeping the minimum wage, there are still plenty of economists who believe that setting a pay floor represents a distortion to the way the labour market works because it reduces the flexibility of the labour market.

Unemployment. A NMW can cause unemployment. A minimum wage may cost jobs because a rise in labour costs makes it more expensive to employ people.

The maintenance of pay differentials. There was a worry that a higher wage rate at the low end of the scale may cause those higher up the pay scale to insist on pay rises to maintain the pay differentials. In theory, this could happen all the way up the pay scale and be very inflationary.

It may not reduce poverty. One of the main advantages of the NMW was its success in reducing poverty by increasing the wage of low-income families. But many households in poverty are struggling precisely because no one in the household has a job. The NMW is useless to the unemployed.

High cost to employers. The bureaucracy involved in complying with the new law, plus the actual cost of the higher wage (assuming productivity improvements are not significant) may force firms to increase the price of their products, which is detrimental to consumers. They may also cut back on expensive training for employees.

Regional differences. The NMW is national. The wage floor is the same rate nationwide. Is that fair? It costs a lot more to live in London than anywhere else in the UK, and yet a struggling cleaner will be paid the same wherever he/she works in the country.