Chapter 8: Analyzing Cells, Molecules, and Systems

Isolating cells and growing them in culture:

Tissue Dissociation:

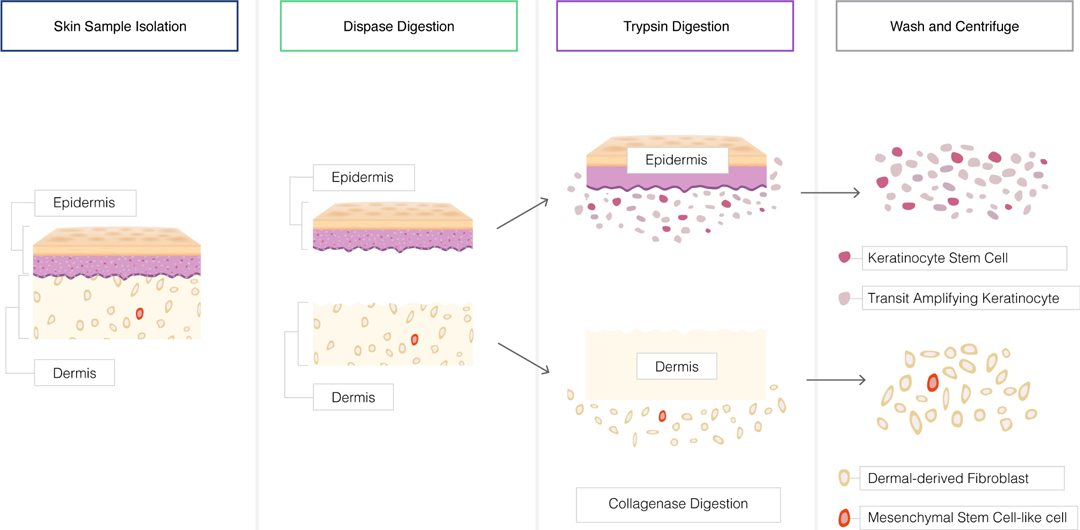

Tissues can be dissociated to obtain a single-cell suspension for cell culture.

Mechanical methods such as mincing, grinding, or shearing can be used to disrupt tissues.

Enzymatic digestion with proteolytic enzymes like trypsin or collagenase can help release cells from the extracellular matrix.

Cell Separation:

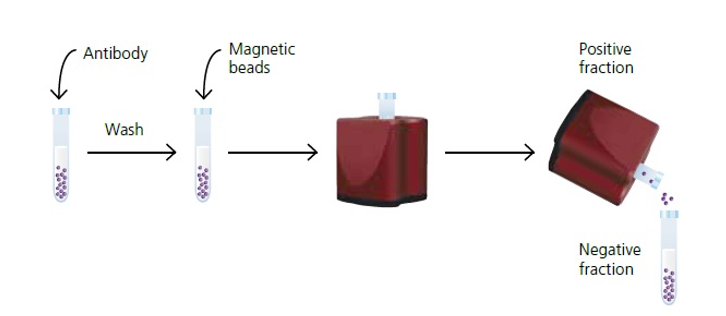

If a specific cell population is desired, cells can be separated based on their physical or molecular properties.

Techniques such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS), or density gradient centrifugation can be employed for cell separation.

Primary Cell Culture:

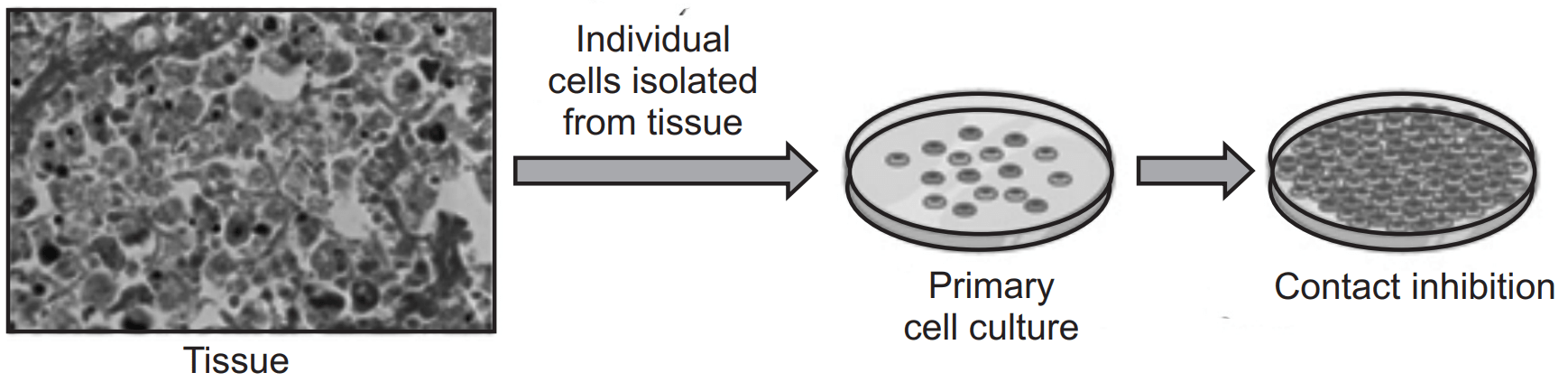

Primary cells are isolated directly from tissues and have a limited lifespan in culture.

Cells are seeded onto culture dishes or plates coated with extracellular matrix proteins to promote cell attachment.

Culture medium containing essential nutrients, growth factors, and supplements is provided to support cell growth and proliferation.

Primary cells can be used for short-term experiments or expanded through serial passaging.

Immortalized Cell Lines:

Immortalized cell lines are derived from primary cells but have undergone genetic modifications to overcome replicative senescence.

Immortalized cells can be cultured indefinitely and are widely used in research.

Common examples include HeLa cells (derived from cervical cancer) and HEK293 cells (derived from human embryonic kidney).

Immortalized cell lines can maintain specific characteristics or be genetically modified to mimic disease conditions.

Cell Culture Conditions:

- Cells require a controlled environment for optimal growth in culture.

- Culture conditions include temperature, humidity, and a specific gas composition (typically 5% CO2 and 95% air).

- Culture medium is supplemented with amino acids, vitamins, salts, and serum (or serum-free alternatives) to provide essential nutrients and growth factors.

- pH is maintained within a physiological range (usually around 7.4) using a buffering system.

Cell Adhesion and Substrates:

- Cells require a suitable substrate for attachment and growth.

- Culture vessels can be coated with extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, or gelatin to enhance cell adhesion.

- Synthetic substrates or hydrogels can also be used to mimic the extracellular matrix environment and provide specific cues for cell behavior.

Cell Proliferation and Passage:

- Cells in culture proliferate and expand over time, forming a monolayer or three-dimensional structures.

- As cells reach confluence, they can be detached using enzymatic (e.g., trypsin) or non-enzymatic methods.

- Passage refers to the process of transferring cells to new culture vessels to maintain cell viability and prevent overgrowth.

- Cells are typically subcultured at a defined ratio to maintain their characteristics and avoid replicative senescence.

Contamination Control:

- Maintaining sterility is crucial to avoid contamination in cell culture.

- Aseptic techniques, including working in a laminar flow hood and using sterile equipment and reagents, are employed.

- Antibiotics and antifungal agents can be added to the culture medium to prevent microbial contamination.

- Regular monitoring and periodic testing for contaminants are essential to ensure cell culture quality.

Quality Control and Characterization:

- Cell lines should be routinely authenticated and characterized to ensure their identity, purity, and functionality.

- Authentication techniques include DNA fingerprinting, short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, and karyotyping.

- Characterization involves assessing cell morphology, growth characteristics, surface markers, and functional assays.

Purifying proteins:

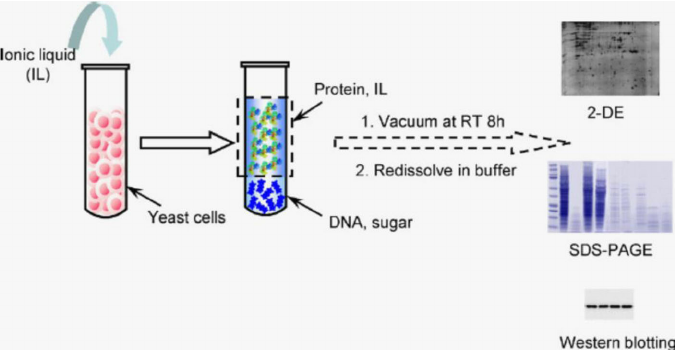

Cell Lysis and Homogenization:

- Cells are lysed to release their contents, including the target protein of interest.

- Various methods can be used, such as sonication, freeze-thaw cycles, or mechanical disruption.

- Lysis buffers containing detergents, salts, and protease inhibitors are used to maintain protein stability and prevent degradation.

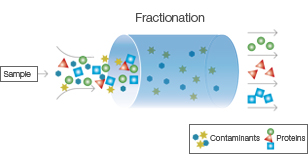

Fractionation:

Cell lysate is subjected to fractionation techniques to separate cellular components based on their size, charge, or solubility.

Common fractionation methods include differential centrifugation, ultracentrifugation, and filtration.

This step helps remove cell debris, organelles, and other macromolecules, allowing for the enrichment of the target protein.

Protein Extraction:

Proteins can be extracted from cellular fractions using various techniques, depending on their physicochemical properties.

Salting out: Precipitation of proteins by adding high concentrations of salts (e.g., ammonium sulfate).

Solvent extraction: Partitioning of proteins based on their solubility in organic solvents or detergents.

Chromatography: Separation of proteins based on their affinity for specific ligands or physical properties.

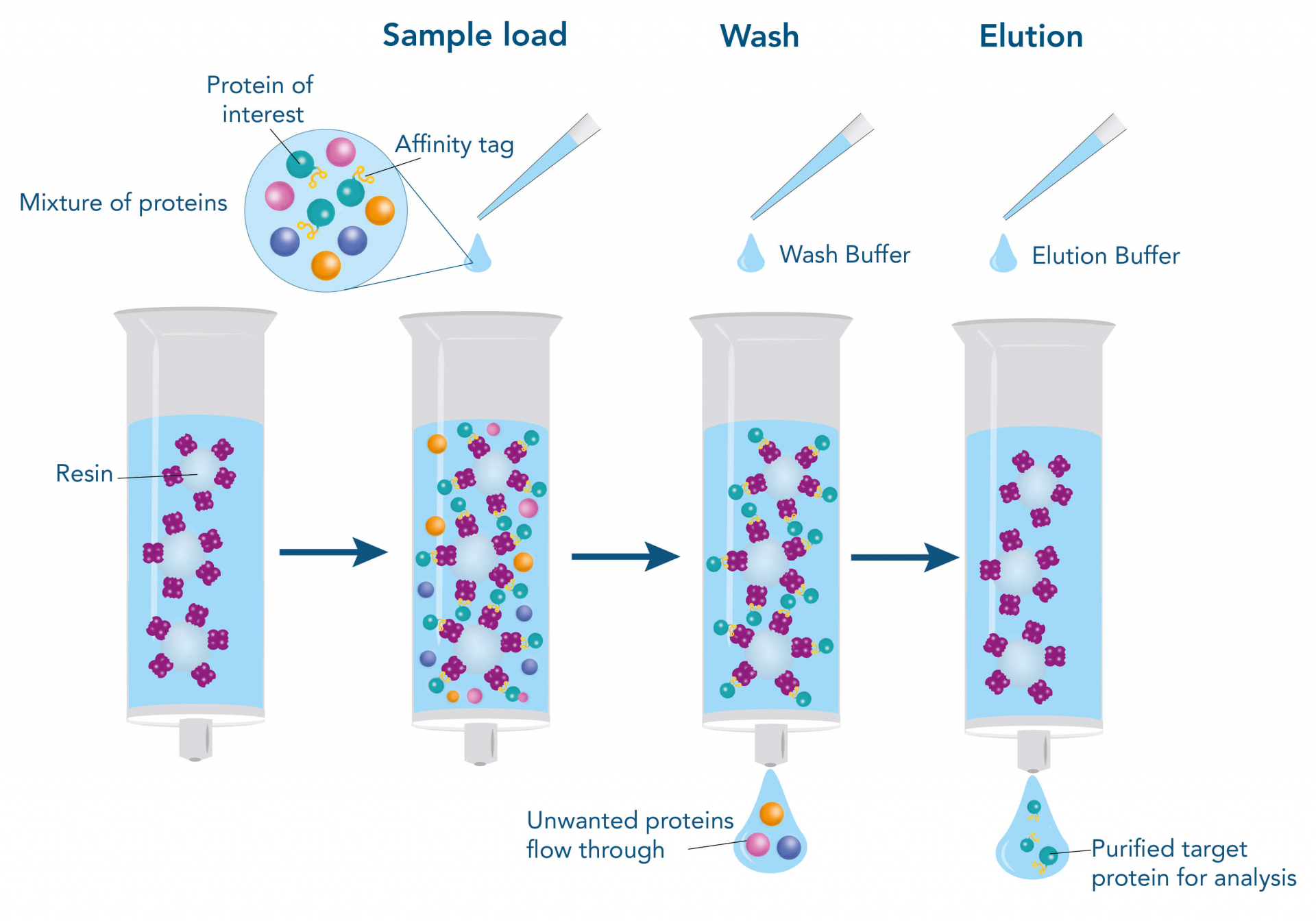

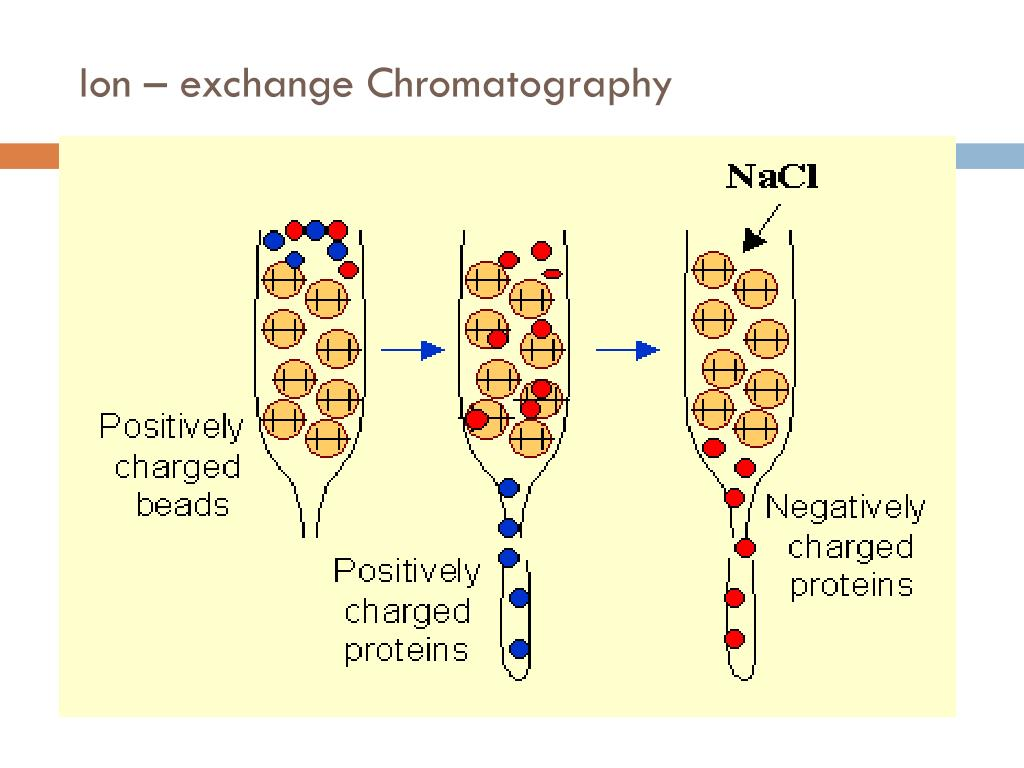

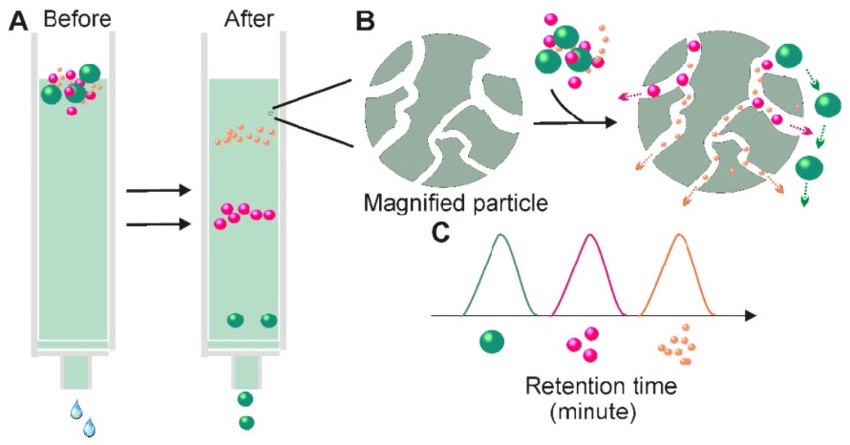

Chromatography Techniques:

Chromatography is the most commonly used method for protein purification, allowing for high resolution and specificity.

Different chromatographic methods can be employed at different stages of purification, including:

Affinity chromatography: Exploits specific interactions between the target protein and an immobilized ligand (e.g., antibody, metal ions, or receptor).

Ion-exchange chromatography: Separates proteins based on their net charge and affinity for charged resin.

Size-exclusion chromatography: Separates proteins based on their size and shape, allowing for the removal of contaminants.

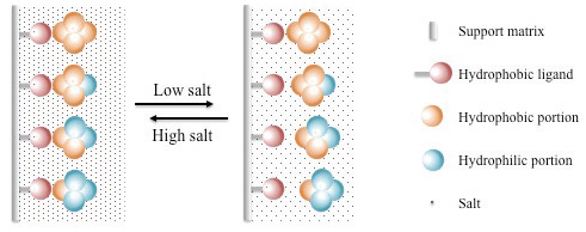

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography: Separates proteins based on their hydrophobicity, utilizing the interaction between the protein and a hydrophobic resin.

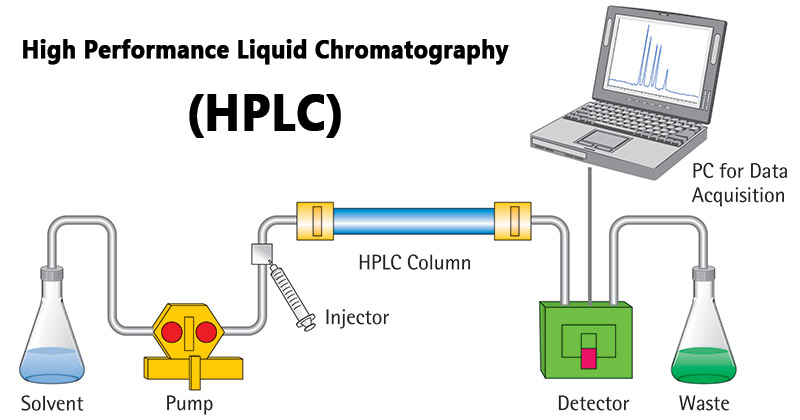

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC): Utilizes advanced liquid chromatography techniques for higher resolution and efficiency.

Protein Analysis:

- Throughout the purification process, protein fractions are analyzed to assess purity and quantity.

- Common methods include sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), western blotting, and enzyme activity assays.

- Spectrophotometry and fluorometry can be used to measure protein concentration and determine purity.

Protein Refolding:

- If a purified protein has lost its native conformation and activity during purification, refolding may be required.

- Refolding techniques involve carefully controlling the protein's environment, including buffer conditions, temperature, and the presence of additives or chaperones.

- Optimization of refolding conditions can restore the protein to its functional form.

Storage and Preservation:

- Purified proteins should be stored under appropriate conditions to maintain their stability and activity.

- Storage temperatures, buffer composition, and the addition of cryoprotectants (e.g., glycerol) or stabilizers can help prevent degradation and denaturation.

- Aliquots of purified protein can be stored at ultra-low temperatures (e.g., -80°C) or lyophilized for long-term preservation.

Analyzing Proteins:

Protein Quantification:

- Protein quantification methods determine the concentration of proteins in a sample.

- Common techniques include the Bradford assay, Lowry assay, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, and spectrophotometric absorbance at 280 nm.

- Quantification is important for ensuring accurate loading of proteins in downstream experiments and comparing protein levels between samples.

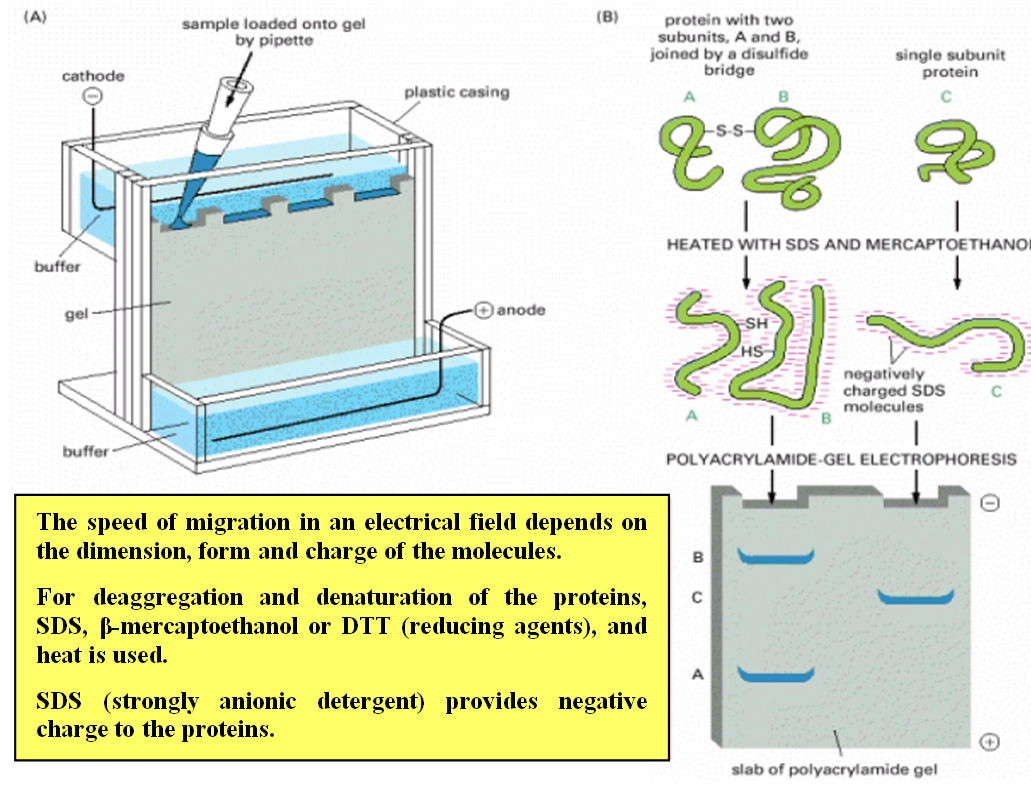

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE):

SDS-PAGE separates proteins based on their size.

Proteins are denatured and coated with SDS, a detergent that imparts a negative charge to the proteins.

The proteins are then loaded into a polyacrylamide gel, and an electric field is applied.

Smaller proteins migrate faster through the gel, while larger proteins migrate more slowly.

SDS-PAGE allows visualization of protein bands and estimation of molecular weight using protein size markers.

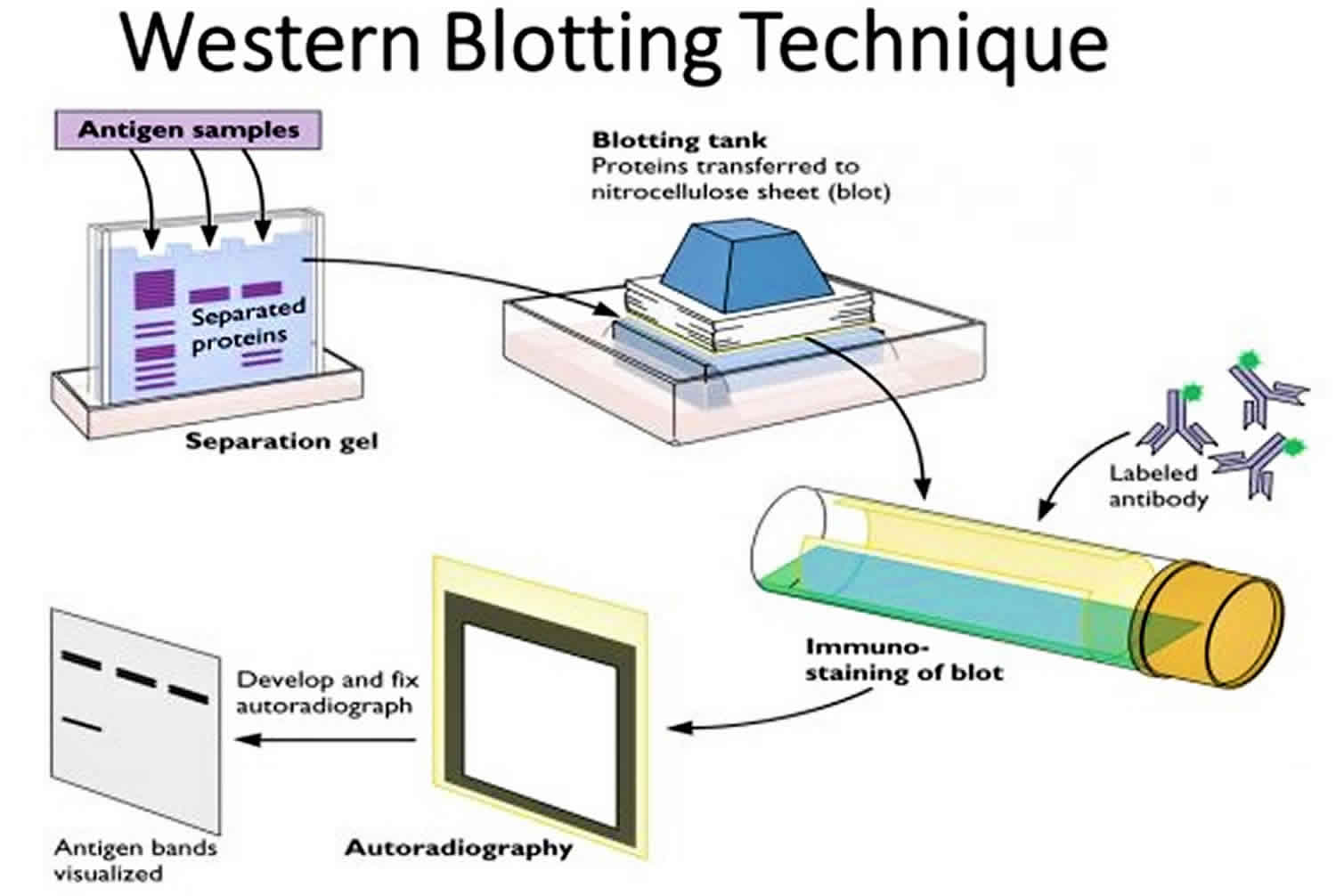

Western Blotting (Immunoblotting):

Western blotting detects and characterizes specific proteins within a complex mixture.

Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are transferred to a membrane (typically nitrocellulose or PVDF).

The membrane is incubated with primary antibodies that recognize the target protein.

Detection is achieved using secondary antibodies conjugated to enzymes or fluorophores, generating a signal that can be visualized.

Western blotting allows quantification of protein expression levels and identification of post-translational modifications.

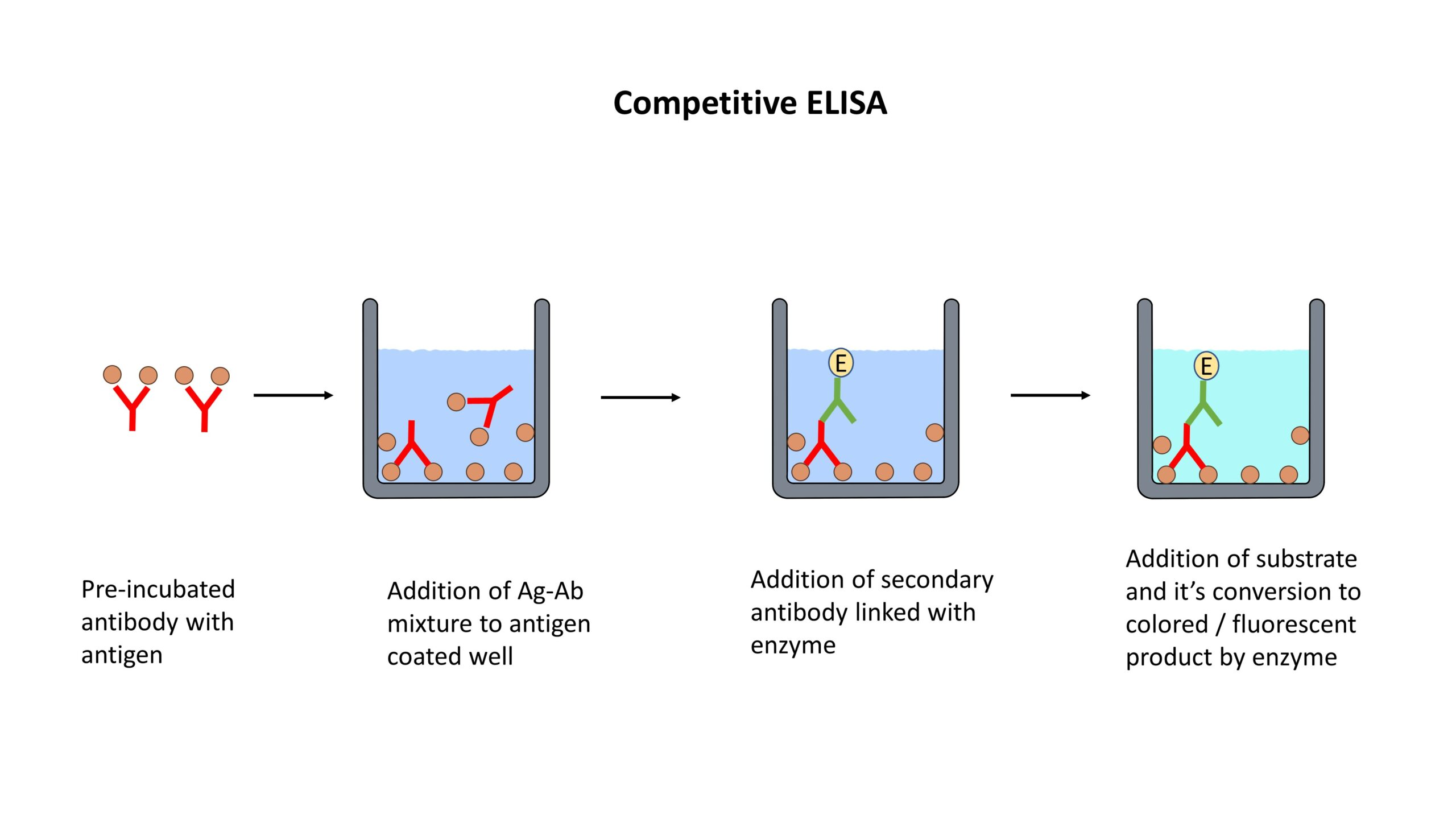

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA):

ELISA detects and quantifies specific proteins using antibodies.

The target protein is immobilized on a solid surface, such as a microplate.

The immobilized protein is then incubated with a primary antibody specific to the target protein.

Detection is achieved using a secondary antibody conjugated to an enzyme, which produces a colorimetric or fluorescent signal.

ELISA is widely used for protein quantification, biomarker analysis, and immunological research.

Mass Spectrometry (MS):

- Mass spectrometry analyzes proteins by measuring their mass-to-charge ratio.

- Proteins are digested into smaller peptides using proteolytic enzymes (e.g., trypsin).

- The resulting peptides are ionized and introduced into the mass spectrometer.

- Mass spectrometers detect and measure the masses of the ions, allowing identification and quantification of the peptides.

- Protein identification is achieved by comparing the obtained peptide masses to protein databases.

- MS can also be coupled with liquid chromatography (LC-MS) to improve peptide separation and identification.

Protein-Protein Interactions:

- Studying protein-protein interactions helps understand protein function and cellular processes.

- Techniques such as co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), pull-down assays, and yeast two-hybrid screening can identify interacting proteins.

- Co-IP involves immunoprecipitating a target protein along with its interacting partners using specific antibodies.

- Pull-down assays use affinity tags or bait proteins to capture interacting partners from a complex mixture.

- Yeast two-hybrid screening utilizes the yeast cell's transcriptional activity to identify protein-protein interactions.

Structural Analysis:

- Determining protein structure provides insights into function and interactions.

- X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy are commonly used methods.

- X-ray crystallography involves crystallizing the protein and analyzing the diffraction pattern produced by X-rays.

- NMR spectroscopy analyzes the interactions between atomic nuclei in the protein to determine its structure in solution.

- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a powerful technique for visualizing protein structures at near-atomic resolution without the need for crystallization.

Proteomics:

- Proteomics involves the large-scale analysis of proteins and their modifications.

- It includes techniques such as 2D gel electrophoresis, protein profiling, and shotgun proteomics.

- Proteomic approaches provide comprehensive insights into protein expression, post-translational modifications, and protein networks.

Analyzing and Manipulating DNA

DNA Extraction:

DNA extraction is the first step in analyzing and manipulating DNA.

Common methods include cell lysis to release DNA, followed by purification steps to remove contaminants such as proteins and RNA.

DNA extraction can be performed from various sources, including cells, tissues, blood, or environmental samples.

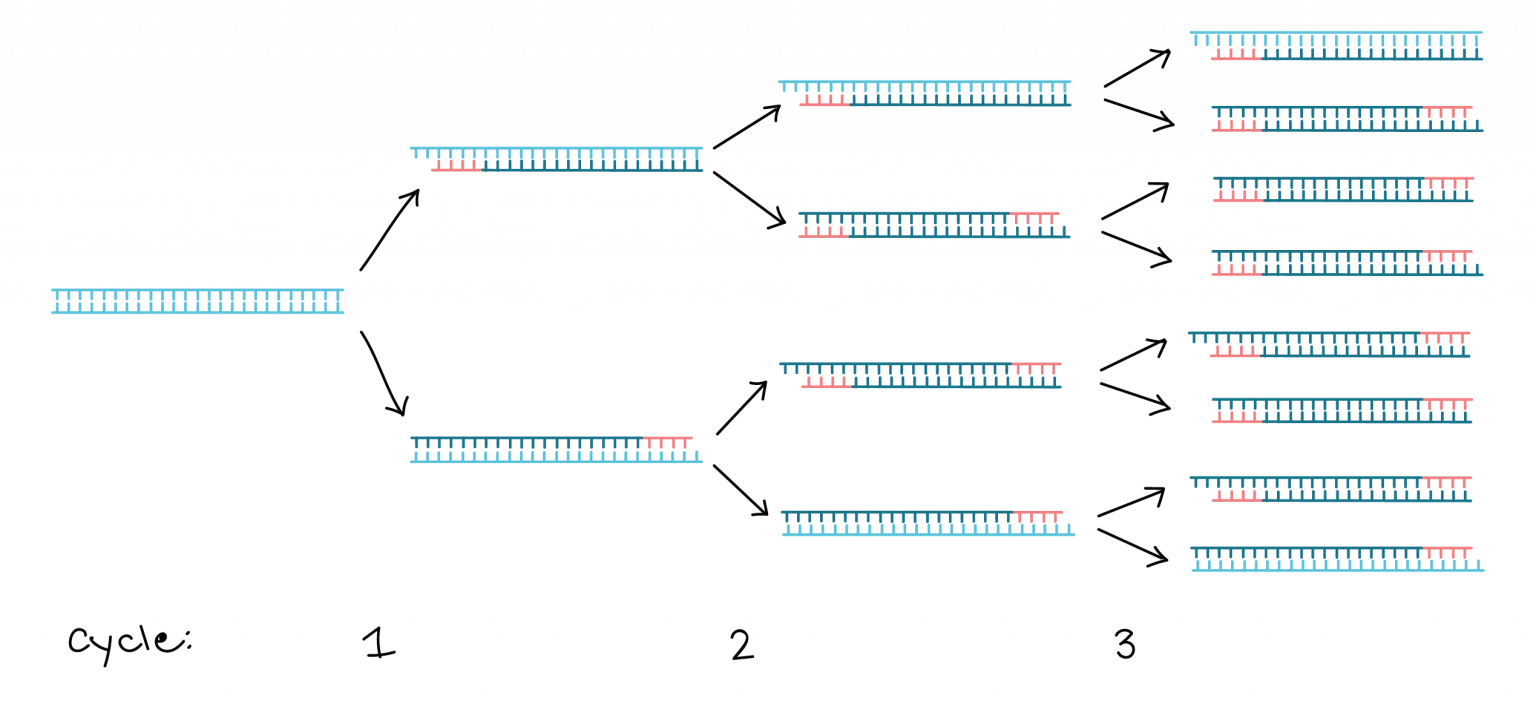

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR):

PCR amplifies specific DNA sequences in vitro.

It involves a series of temperature cycles that denature the DNA, anneal primers specific to the target sequence, and extend the DNA using a DNA polymerase enzyme.

PCR enables the amplification of a small amount of DNA into millions of copies, allowing for further analysis or manipulation.

Gel Electrophoresis:

Gel electrophoresis separates DNA fragments based on their size and charge.

DNA samples are loaded into wells of an agarose or polyacrylamide gel and subjected to an electric field.

Smaller DNA fragments migrate faster through the gel, while larger fragments migrate more slowly.

DNA bands can be visualized using fluorescent dyes, intercalating agents, or specific DNA stains.

DNA Sequencing:

- DNA sequencing determines the order of nucleotide bases in a DNA molecule.

- Sanger sequencing, also known as chain-termination sequencing, was the first widely used method.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques, such as Illumina sequencing, enable high-throughput sequencing of DNA.

- DNA sequencing is crucial for studying genetic variations, identifying mutations, and understanding genomic structures.

DNA Cloning:

- DNA cloning involves the replication of a specific DNA fragment and its insertion into a vector for replication in a host organism.

- The DNA fragment of interest is typically inserted into a plasmid or a viral vector.

- Cloning allows for the production of large quantities of DNA, studying gene function, and generating recombinant proteins.

Restriction Enzymes:

- Restriction enzymes, also known as restriction endonucleases, cleave DNA at specific recognition sites.

- They recognize short DNA sequences and cut the DNA, generating fragments with sticky ends or blunt ends.

- Restriction enzymes are widely used in DNA cloning, genetic engineering, and molecular biology techniques.

DNA Modification:

- DNA can be modified by various methods to introduce changes in its sequence or structure.

- Site-directed mutagenesis allows for the introduction of specific mutations in the DNA sequence.

- DNA modification techniques, such as methylation or acetylation, can alter gene expression patterns and epigenetic modifications.

DNA Hybridization:

- DNA hybridization involves the pairing of complementary DNA strands.

- It is widely used in techniques such as Southern blotting, Northern blotting, and DNA microarrays.

- DNA probes, labeled with fluorescent or radioactive markers, hybridize to specific DNA sequences of interest.

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing:

- CRISPR-Cas9 is a revolutionary genome editing tool.

- It utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) to target specific DNA sequences, and the Cas9 nuclease introduces precise cuts at the target site.

- CRISPR-Cas9 allows for gene knockout, gene insertion, or gene editing with high efficiency and specificity.

- It has transformed genetic research, disease modeling, and potential therapeutic applications.

Studying gene expression and function

Transcriptomics:

- Transcriptomics investigates gene expression patterns by analyzing the complete set of RNA molecules (transcriptome) in a cell or tissue.

- Techniques such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provide a comprehensive view of the transcriptome, allowing the identification of expressed genes, alternative splicing events, and noncoding RNAs.

- Differential gene expression analysis compares gene expression levels between different conditions or cell types, providing insights into gene function and regulatory mechanisms.

Gene Knockout and Knockdown:

- Gene knockout involves disrupting or inactivating a specific gene to study its function.

- Techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to create targeted mutations in the DNA sequence, leading to loss-of-function of the gene.

- Gene knockdown utilizes RNA interference (RNAi) or antisense oligonucleotides to reduce the expression of a specific gene, allowing the assessment of its role in cellular processes.

Functional Genomics:

- Functional genomics aims to understand the function of genes and their interactions within biological systems.

- Techniques such as gene expression profiling, protein-protein interaction analysis, and high-throughput screening are used to investigate gene function.

- Large-scale studies, such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and CRISPR-based genetic screens, provide insights into the relationships between genotype, gene expression, and phenotype.

Reporter Assays:

- Reporter assays allow the measurement of gene expression levels and promoter activity.

- A reporter gene, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) or luciferase, is fused to the promoter region of the gene of interest.

- The activity of the reporter gene reflects the transcriptional activity of the target gene.

- Reporter assays are used to study the regulation of gene expression, identify cis-regulatory elements, and assess the effects of mutations or regulatory factors.

Gene Expression Analysis:

- Techniques such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) enable the quantification of gene expression levels.

- RT-PCR converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified and detected.

- qPCR allows for the quantification of gene expression in real-time using fluorescent dyes or probes.

- Gene expression analysis is used to study gene regulation, validate transcriptomic data, and assess changes in gene expression under different conditions or treatments.

Functional Assays:

- Functional assays assess the biological activity of genes or gene products.

- They can include assays for enzyme activity, protein-protein interactions, protein localization, or protein function.

- Functional assays help elucidate the role of genes in specific cellular processes and pathways.

Mathematical Analysis of Cell Functions

Modeling Cellular Processes:

- Mathematical models are used to describe and simulate various cellular processes, including signaling pathways, gene regulation, metabolic networks, and cell population dynamics.

- Models capture the behavior of biological systems using mathematical equations that represent the interactions and dynamics of cellular components.

- They provide a quantitative framework to understand complex cellular phenomena and make predictions about cellular behavior.

Differential Equations:

- Differential equations are a fundamental tool in mathematical biology.

- They describe how variables change over time based on their rates of change.

- Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) model intracellular processes such as enzyme kinetics, gene expression, and signaling dynamics.

- Partial differential equations (PDEs) describe spatially distributed phenomena, such as cell movement, tissue growth, and reaction-diffusion processes.

Systems Biology:

- Systems biology aims to understand biological systems as a whole by integrating experimental data with mathematical modeling.

- It focuses on analyzing and modeling the interactions between various components, such as genes, proteins, and metabolites, to understand emergent properties and system-level behavior.

- Systems biology approaches include network analysis, dynamical modeling, and parameter estimation to study cellular processes comprehensively.

Network Analysis:

- Network analysis characterizes cellular processes as networks of interconnected components.

- Graph theory is used to model and analyze these networks.

- Network analysis can reveal important nodes (genes, proteins) and interactions, identify key regulatory elements, and predict cellular behaviors.

- It helps uncover the underlying organizational principles of biological systems and identify potential targets for intervention.

Parameter Estimation:

- Parameter estimation involves determining the values of unknown parameters in mathematical models using experimental data.

- It is crucial for model calibration and validation.

- Various optimization techniques, such as least squares fitting, maximum likelihood estimation, or Bayesian inference, are used to estimate parameter values that best fit experimental data.

Computational Simulations:

- Computational simulations involve running mathematical models to simulate cellular processes and predict their behavior.

- Simulations can reveal insights into complex dynamic behaviors, test hypotheses, and explore the effects of perturbations.

- They provide a platform for in silico experiments, allowing researchers to explore the behavior of a system under different conditions or parameter values.

Model Validation and Experimental Design:

- Mathematical models need to be validated against experimental data to ensure their accuracy and predictive power.

- Model validation involves comparing model predictions with experimental observations.

- Model-guided experimental design uses mathematical models to optimize experimental protocols, identify key measurements, and explore system behavior in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

Statistical Analysis:

- Statistical analysis is crucial for evaluating the significance of experimental results and validating mathematical models.

- It includes hypothesis testing, confidence interval estimation, regression analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

- Statistical methods help determine the reliability of experimental observations, assess model performance, and make robust conclusions.