L3- Parental Care

African jacana→ male provides most of the care, protective brooding

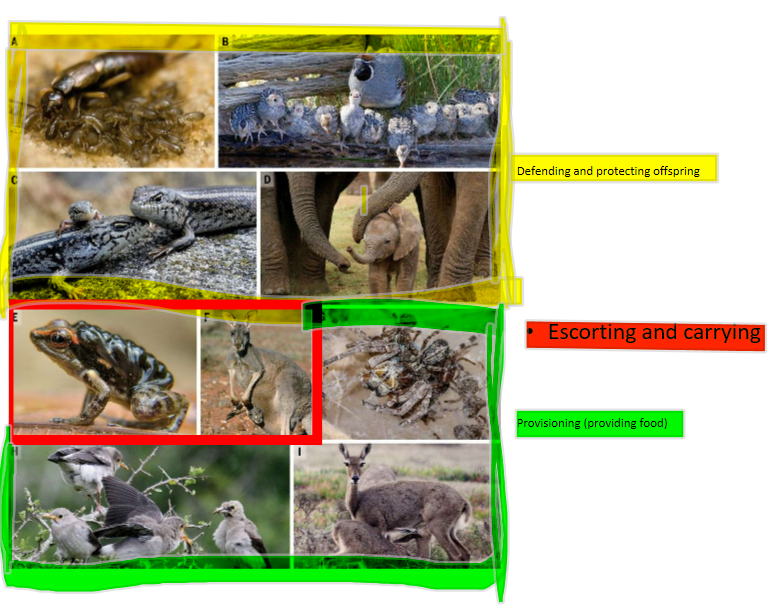

Parental care:

is a diverse trait

varies within species in:

the form it takes

level and duration

extent provided by each/both parents

encompasses a huge range of behaviours e.g.

Example of parental care→ mouth brooding:

seen in many fish species

e.g. female cichlids- mouth brood for 3-6 weeks, wont feed themselves→ cost of care but benefit to offspring

Parental care varies massively across species:

provisioning of care occurs in 1% of insect species

parents protect from predators→ cleaning, carrying, warming offspring

some form of parental care occurs in 30% of fish families, amphibians (6-15% in anurans, 20% of salamanders) and reptiles (all crocodiles, 1% of lizards, 3% of snakes)

less common in ectotherms→ most parental care occurs before they are born (e.g. egg guarding) but postnatal care can occur (e.g. mouth brooding)

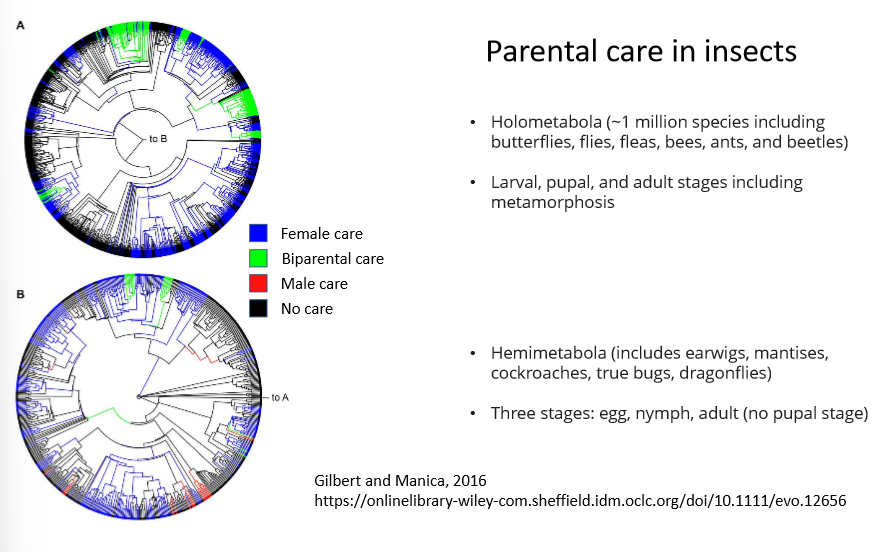

Parental care in Insects-

estimated ancestral states of parental care across different groups of insects:

phylogeny at the top of Holometabola→

have a mixture of female, biparental and no care

have no male only care

the fact that they have larval, pupal and adult stages may influence types of care

phylogeny of Hemimetabola→

have wider ranges of parental care including male only care

may be because there is no pupil stage

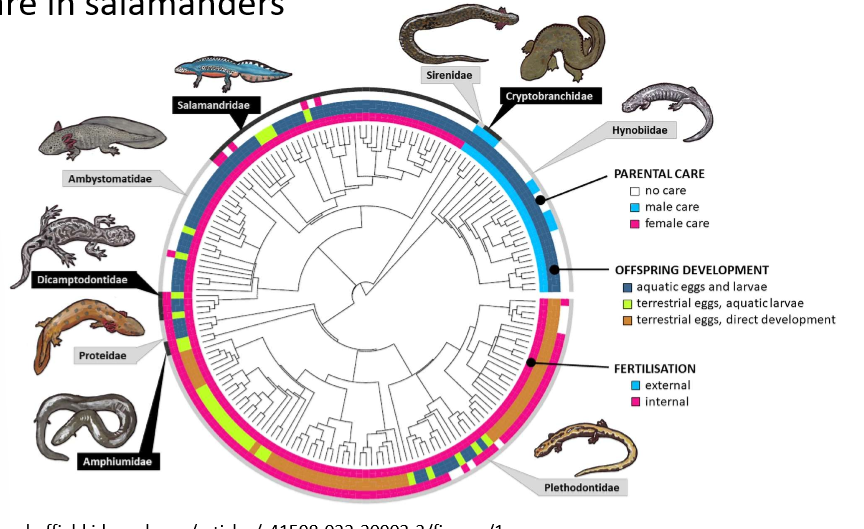

Parental care in Salamanders-

there are only limited cases of male only care and is constrained to species with external fertilisation (light blue)

→ suggests male care can only evolve in species with external fertilisation

females are less tied to offspring reproduction→ easier to desert or look for other mating opportunities

there are examples of female only care→ some groups is almost ubiquitous

→ shows importance in modes of fertilisation and offspring development

offspring development has many different forms in salamanders:

aquatic eggs- aquatic larvae

terrestrial eggs- aquatic larvae

terrestrial eggs- direct development

→ could be important in determining outcomes of paternal care

Parental care is not fixed at the level of species:

there can be more than one mode of parental care in a population, within species→ e.g. 3 closely related species of plover:

White-fronted, Madagascar, Kittliz’s Plovers→ all same genus, co-occur on salt flats in Madagascar, share same environment

White-fronted and Madagascar have biparental care during incubation and brooding whilst Kittlitz’s has uniparental and biparental care

Q→ why are these closely related species that share the same habitats responding differently in terms of parental care strategies?

→ answer is in papers to be discussed

some species show more than one mode in a population e.g. burying beetles, acorn woodpeckers, Galilee St. Peter’s fish and gray wolf

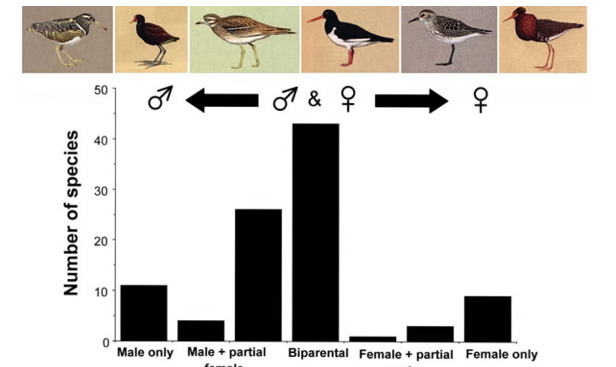

Why we see these differences in parental care form can be summarised into these series of questions:

What are the principal benefits of parental care?

Why does the extent of parental care vary so widely between species?

Why do only females care for eggs or young in some animals, only males others, and both parents in a few?

To what extent is parental care adjusted to variation in its benefits to offspring and its costs to parents?

How do parents divide their expenditure between their sons and daughters?

Extent of parenting-

broad idea that the extent of parenting is defined in terms of growth and survival of offspring, depends on the offspring themselves, has trade-offs

demands of the offspring are very important e.g. skimmer provisioning its young with fish caught, nest is just a scraping of sand

links to the precocial-altricial spectrum:

mostly seen in birds, quite a bit in mammals, looking at wider taxa now

is based on appearance and behaviour

idea was first proposed by Margret Morse Nice→ developed a classification scheme based on observations of different developmental behavioural characteristics of different species (Rick Clefs uses a similar scheme)

precocial→ born with downy feathers, hatch with eyes open, are mobile, able to feed themselves within a few hours of hatching, mostly ground nesting e.g. Wood Duck

semi-precocial→ more development, seabird species- cant immediately go out and catch fish e.g. Brown Nuddy

altricial→ born with no/few downy feathers (naked), hatch with eyes closed, nest bound, entirely reliant on parents food, parents regularly attend nest/are near offspring e.g. American Robin

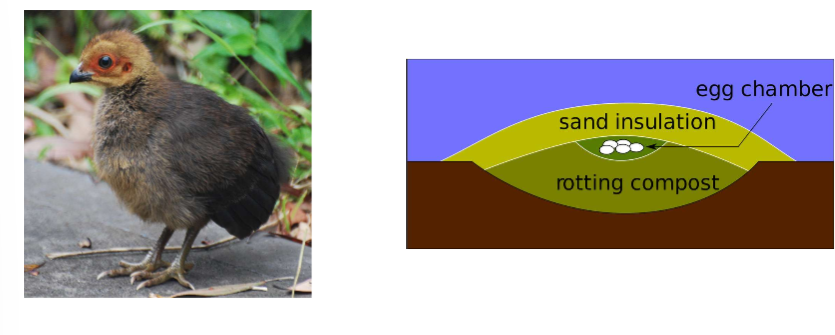

super precocial→ abandoned by parents as soon as eggs are laid e.g. Australian brush-turkey:

nest is a mound of rotting compost that generates heat, lay 20 eggs, cover with sand for insulation, creates a steady environment for eggs to develop in, parents leave them

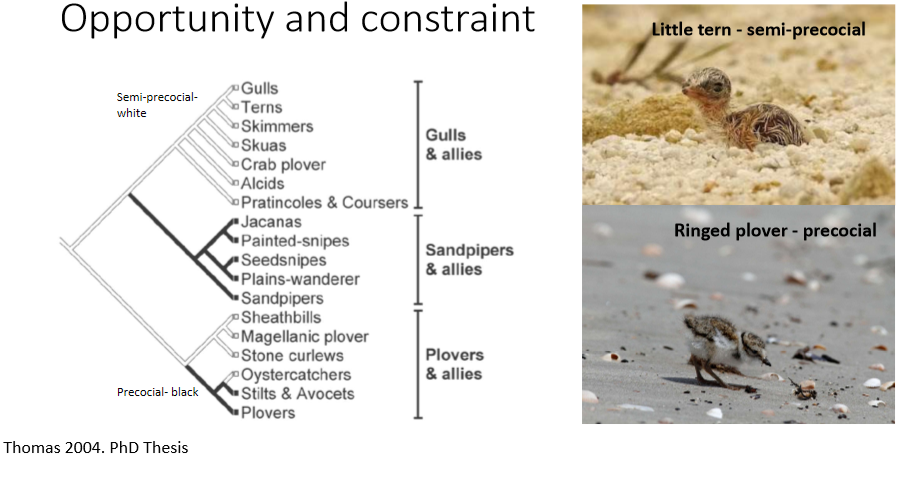

see varieties of developmental modes within closely related species e.g. phylogeny of shorebirds

precocial-altricial spectrum is important for evolution of parental care in these species:

morphology is similar across species in terms of thermal regulatory abilities but there are differences in if they can feed

whether they can forage constrain potential opportunities of mating for parents

evolutionary transitions from biparental care to uniparental care→

contingent on the prior evolution of precociality→ only see uniparental care if that lineage has already evolved towards precociality

no species in this had biparental care

→ suggests uniparental care is much more likely to evolve when demands of offspring are reduced

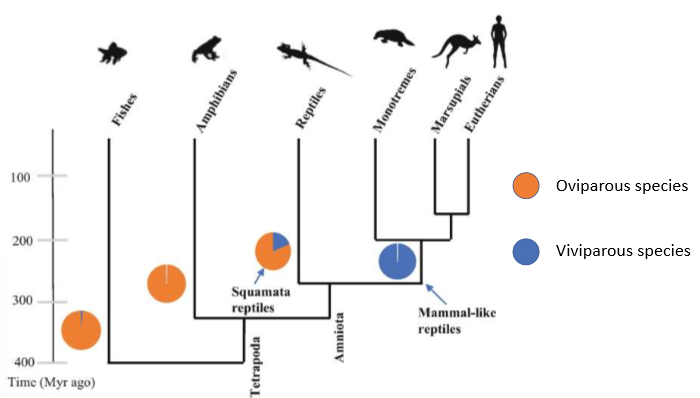

Forms of reproductive modes-

oviparity- parent lays eggs

viviparity- parent gives birth to live young

varies but is more conserved in terms of major groups:

most mammals are viviparous

most fish and amphibians are oviparous

reptiles have a mixture

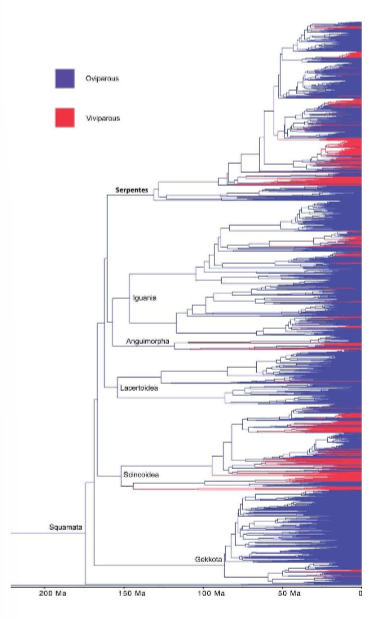

squamates have had >100 transitions across species of switches between o and v

controversy of direction of change but is harder to switch back to a development of an egg

discussions will look at transitions between these states and the constraints there are

if only evolution from oviparous to viviparous is possible, why do we still see oviparous at all?

something is happening at the macroevolutionary level

may oviparous have higher speciation rates on reproductive mode, which maintains oviparous species

oviparity and viviparity are constrained evolutionarily→ don’t change across tree of life generally

there are examples within reptiles of variation within species e.g. 3 species that vary in reproductive mode:

oviparous, viviparous, viviparous with transitional form of pregnancy

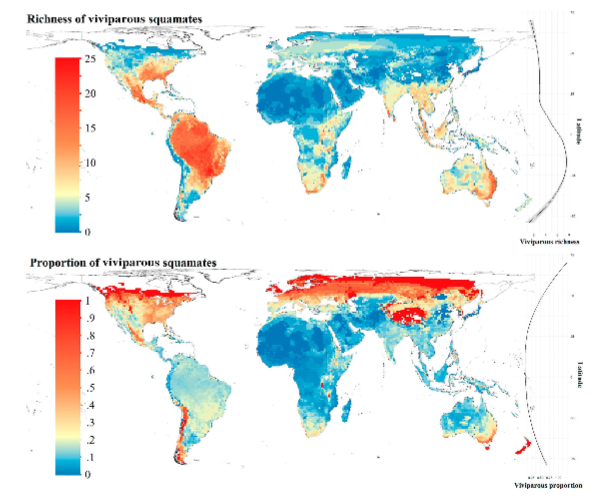

reproductive mode varies spatially:

mapped where there are high proportions of viviparous squamates→ SA, central/north america, east coast of Australia east coast

mapped where there are high proportions viviparous squamates out of the whole species→ SA is now low, more northern, temperate, boreal, edge of tundras

→ potentially environmental/climactic drivers for the evolution of this

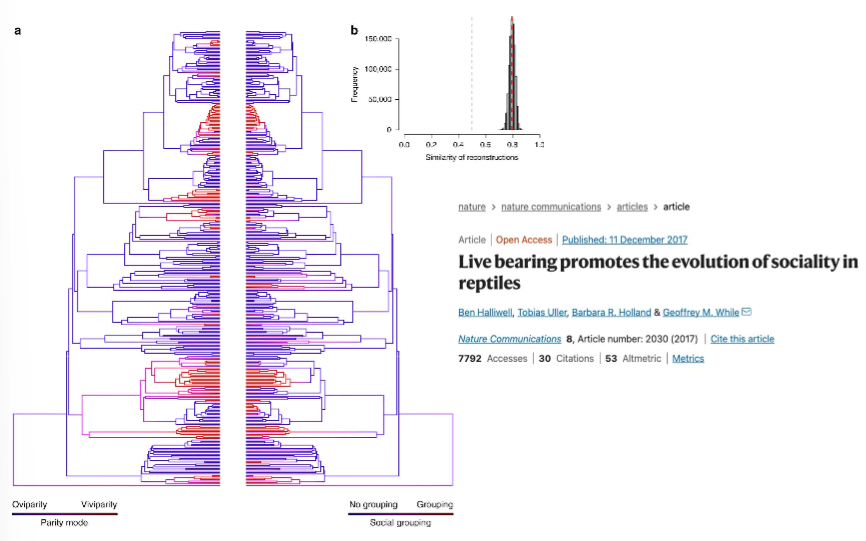

reproductive mode links closely to sociality e.g. viviparous reptiles are more likely to display sociality (live in groups)

Constraint and opportunity:

demands of the offspring can constrain the form, duration and length of care→ lower offspring demands provide opportunity for a wide range of modes of care

if both parents are not required to ensure survival one (or both) can abandon the brood→ doesn’t mean they will though

adults avoid cost of care through desertion→ could be beneficial for adult survival (reduced energy costs) or for seeking further mating opportunities

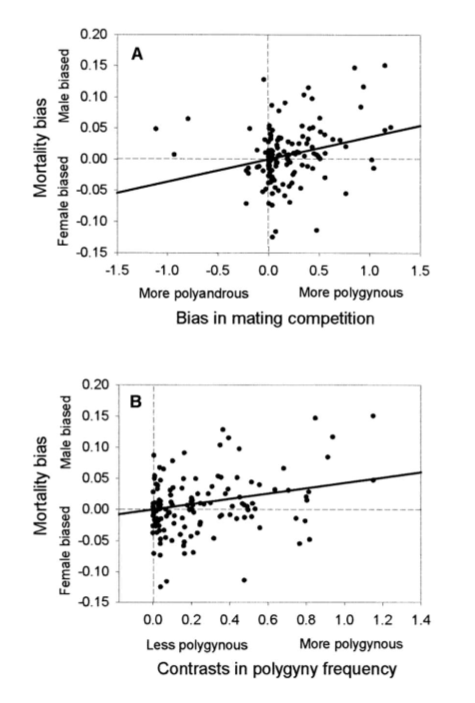

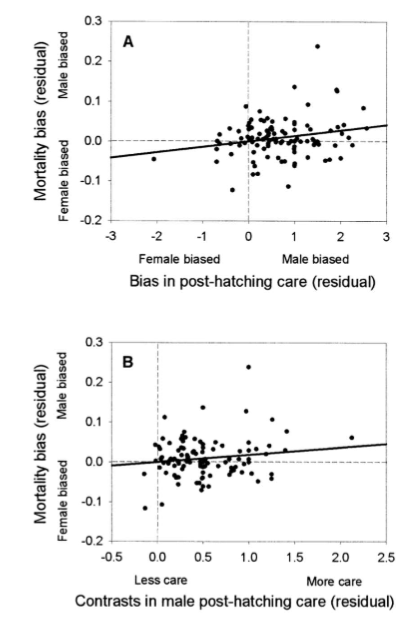

Sex biased survival-

suggests where costs and benefits are when providing care

sexual selection theory predicts higher cost of reproduction for the sex with more intense intrasexual competition

parental care theory predicts higher mortality for the care-giving sex

study looking at 194 cases where females have significantly higher annual mortality than males

method→ assessed the degree of mating competition- polyandrous (females desert and compete) vs polygamous (males desert and compete)

results→

High mortality in males when male-male competition is stronger (supports sexual selection hypothesis)

mortality is more male biased in more polygamous species

→ supports the sexual selection hypothesis

method→ looked at post-hatching parental care

results→

male mortality cost increases as they provide parental care

don’t see the same in females

→ females already have a high cost of reproduction in producing and laying/carrying the egg (higher mortality than males), and so the effects of care on mortality are only detectable in males

→ is seen overall on average, regardless of mode of care

Oher than direct costs of parental care, how could sex-biased mortality influence the decisions of females and males of whether to provide care?

direct costs of parental care

mating opportunities/social environment e.g. snowy plovers:

6 year study in California of breeding demography

observed that females deserted 6 days after hatching and males attended for 29-47 days post-hatching

after desertion, 22 /60 females renested with new mates and 10/18 males that deserted early remated

why are females more likelt to desert?

Males outnumber females ~1.4 : 1→ imbalance in population, more likely to find unmated male

→ social environment need to be studied over multiple field seasons but are important in determining whether individuals will desert

has a follow up study: Does demographic bias in sex ratios generate different opportunities for mating for males and females and therefore shift the balance between the costs of care and benefits of desertion?

4 discussions→

Parental care and the social environment→ how social environment can be an important determinant of parental care

Consequences of parental care→ how parental care can determine variation in other traits, macro evolutionary consequences, broader scale

Avian chick development and the altricial-precocial spectrum

The macroevolution and macroecology of reproductive mode→ how and why do reproductive mode vary across the tree of life and drivers of this?