Sac 2 Notes - Chapter 4

Chapter 4A - Enzymes That Manipulate DNA

Endonucleases

Overview

Scientists use a range of ‘molecular scissors’ known as endonucleases to cut DNA.

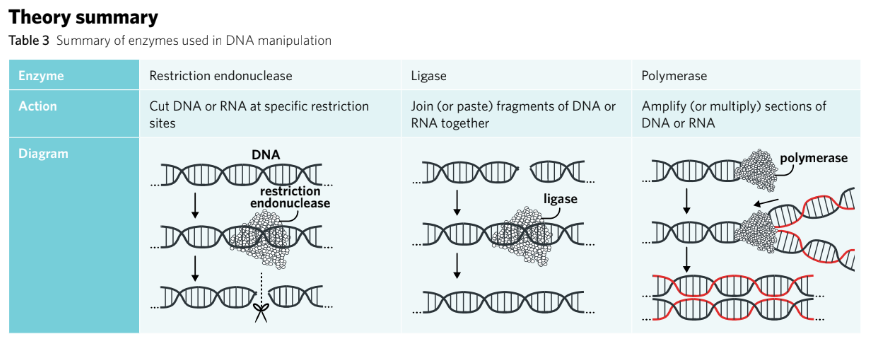

Theory details

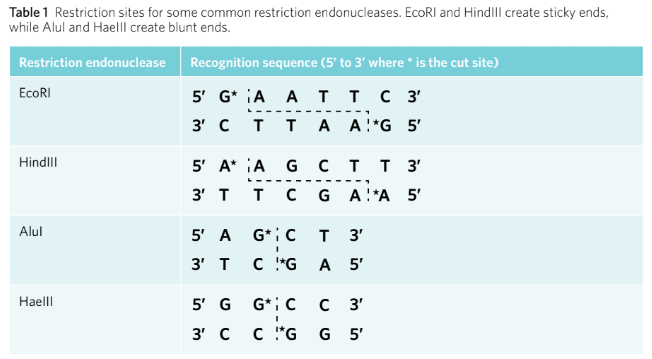

Endonucleases are enzymes responsible for cutting strands of DNA.

When targeting specific recognition sites, they are known as restriction endonucleases.

They cleave the phosphodiester bond of the sugar-phosphate backbone that holds DNA nucleotides together.

The process of cutting is referred to as ‘restriction endonuclease digestion’.

Often sourced from bacteria, produced as a defence against viral DNA.

Names are based on the bacteria from which they were discovered (e.g. EcoRI from E. coli).

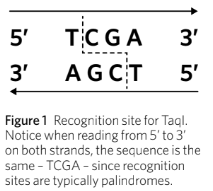

Recognition sites are usually four to six nucleotides long and are specific to each enzyme.

Recognition site sequences are generally palindromes.

Ends created by endonucleases:

Blunt end endonucleases (e.g. AluI) cut DNA in the middle of the recognition site, resulting in a straight cut.

Sticky end endonucleases (e.g. EcoRI) cut staggeredly, resulting in overhanging nucleotides.

Sticky ends are advantageous for ensuring correct orientation when inserting genes.

Endonucleases either create sticky ends or blunt ends. Blunt end endonucleases, such as AluI, cut DNA in the middle of the recognition site, which results in a straight cut and no overhanging nucleotides. Sticky end endonucleases, such as EcoRI, do not cut in the middle of the recognition site, resulting in a staggered cut with overhanging, unpaired nucleotides (Figure 2). They are called ‘sticky’ because the unpaired nucleotides will be attracted to, or want to stick to, a complementary set of unpaired nucleotides. Sticky end endonucleases have the advantage of ensuring an inserted gene is orientated correctly when manipulating DNA.

Definitions

Endonuclease: an enzyme that breaks the phosphodiester bond

between two nucleotides in a polynucleotide chain

Recognition site: a specific target sequence of DNA upon which

Restriction endonuclease: act restriction endonuclease: any enzyme that acts like molecular scissors to cut nucleic acid strands at specific recognition sites. Also known as a restriction enzyme

Ligases

Overview

Ligases are enzymes that join two fragments of DNA or RNA together.

Theory details

Ligases are enzymes that join two fragments of DNA or RNA, acting like molecular glue. To do this, the enzyme will catalyse the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the two fragments to merge them together. There are two main types of ligase enzymes: DNA ligase, which joins two DNA fragments, and RNA ligase, which joins two RNA fragments.

Essentially, ligase enzymes function as the reverse of endonucleases. However, they lack the specificity of restriction endonucleases – meaning they can join together any blunt or sticky ends. This is because the substrates for this enzyme are the sugar and phosphate groups of the DNA or RNA, rather than specific nitrogenous bases which is the case for restriction endonucleases.

Summa

rised Version

Ligases catalyse the formation of phosphodiester bonds to merge two fragments.

Two main types: DNA ligase (joins DNA) and RNA ligase (joins RNA).

Function as the reverse of endonucleases, lacking specificity of restriction endonucleases.

Can join any blunt or sticky ends since substrates are the sugar and phosphate groups instead of specific nitrogenous bases.

Definitions

Ligase: an enzyme that joins molecules, including DNA or RNA, together by catalysing the formation of phosphodiester bonds

Polymerases

Overview

Polymerases add nucleotides to DNA or RNA, which can lead to copying entire genes.

Theory details

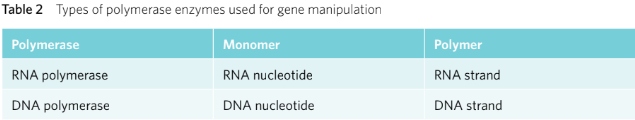

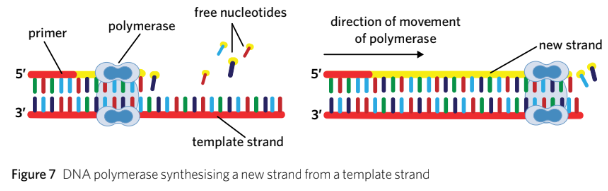

Polymerases synthesise polymer chains from monomer building blocks. There are two particular polymerases used for gene manipulation, RNA polymerase and DNA polymerase (Table 2).

While RNA polymerase is primarily used in the transcription of genes, DNA polymerase is used in the replication or amplification of DNA. For example, in forensic medicine, when scientists are testing a sample they often have a very small amount of DNA available. DNA polymerase can be used to synthesise more strands of DNA, thereby amplifying the DNA.

Polymerases require a primer to attach to the start of a template strand of DNA. Primers are short single-stranded chains of nucleotides that are complementary to the template strand. Once attached to the primer, the polymerase enzyme can read and synthesise a complementary strand to the template strand in a 5’ to 3’ direction.

Summarised Version

Synthesises polymer chains from monomer building blocks.

Two types: RNA polymerase (used for transcription) and DNA polymerase (used for replication/amplification).

DNA polymerase amplifies small DNA samples in forensic medicine.

Polymerases require a primer to attach to the start of a template strand.

Primers are short, single-stranded chains of nucleotides complementary to the template.

Once attached, polymerases synthesise complementary strands in a 5’ to 3’ direction.

Definitions

Polymerase: polymerase an enzyme that synthesises a polymer from monomers, such as forming a DNA strand from nucleic acids

Primer: a short, single strand of nucleic acids that acts as a starting point for polymerase enzymes to attach

Theory summary

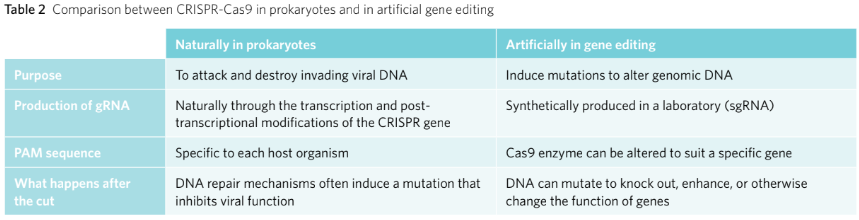

Chapter 4B - CRISPR-Cas9

CRISPR-Cas9 in bacteria

Overview: CRISPR is a naturally occurring sequence of DNA found in bacteria that plays an important role in their defence against viral attacks.

Theory details

What is CRISPR?

Bacteria are susceptible to viral attacks from bacteriophages, similar to how humans can catch a cold from a virus.

When a virus infects a bacterium, it does not cause temporary illness; instead, it leads to more severe consequences.

The virus inserts its DNA or RNA into the bacterium.

Once inside, the virus hijacks the bacterium's cellular machinery to produce its own proteins and nucleic acids.

As the virus replicates, it eventually causes the bacterium to lyse (burst) and die.

This process releases viral particles that can infect other bacterial cells.

In response to these threats, bacteria have evolved the CRISPR-Cas9 system over generations to protect themselves from bacteriophage attacks.

When a bacterium encounters a virus, it takes a ‘mugshot’ by storing viral genetic material in its genome.

During subsequent invasions, the bacterium transcribes the ‘mugshot’ DNA and attaches it to an endonuclease called Cas9.

The transcribed mugshot is complementary to the viral DNA, ensuring Cas9 only destroys the invading virus and not bacterial nucleic acids.

CRISPR-Cas9 acts as a primitive adaptive immune system in bacteria, defending against viral invasion.

Scientists discovered this system in 1987, but its potential applications weren't recognized until later.

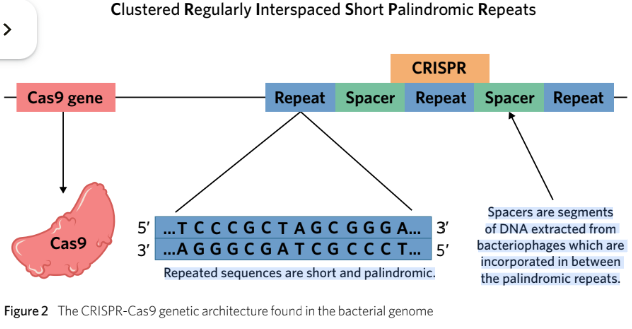

CRISPR is identifiable in the bacterial genome as a section of DNA containing short repeated sequences of nucleotides that read the same forwards and backwards.

The clustered repeats are interrupted by spacer DNA, which represents the viral ‘mugshot’ from bacteriophages for recognition during future invasions.

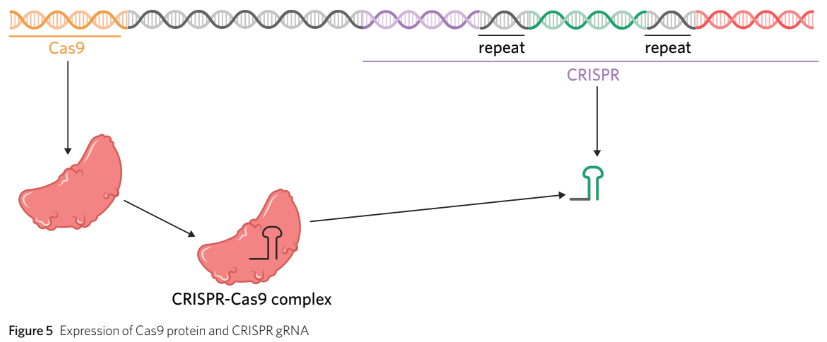

CRISPR sequences are always located downstream of the gene for Cas9.

How the CRISPR-Cas9 defence system works

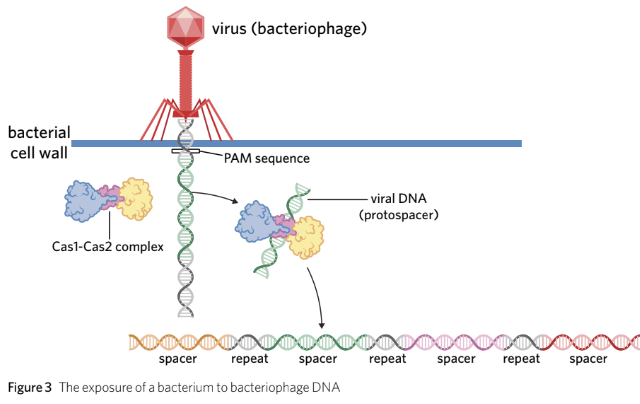

- When a bacterium is infected by a bacteriophage, there are three steps to fighting the virus with the CRISPR-Cas9 system: exposure, expression, and extermination. - **Exposure**: - The bacteriophage injects its DNA into the bacterium. - The bacterium identifies the viral DNA as a foreign substance. - Cas1 and Cas2, CRISPR-associated enzymes, cut out a short section of the viral DNA, known as a protospacer (typically ~30 nucleotides long). - The protospacer is introduced into the bacterium’s CRISPR gene to become a spacer.

Expression involves transcription of CRISPR spacers along with half a palindrome from the repeats on either side.

The transcribed spacers are converted into an RNA molecule known as guide RNA (gRNA).

gRNA binds to Cas9 to form a CRISPR-Cas9 complex.

The CRISPR-Cas9 complex is directed to any viral DNA inside the cell that is complementary to the gRNA.

gRNA can form a hairpin loop-like structure from the transcribed palindromic repeats on either side of the spacer

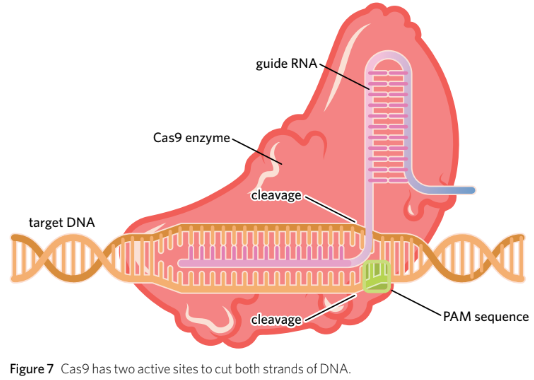

- **Extermination**: - The CRISPR-Cas9 complex scans the cell for invading bacteriophage DNA that is complementary to the ‘mugshot’ on the gRNA. - Upon finding complementary DNA, Cas9 cleaves the phosphate-sugar backbone to inactivate the virus. - Cas9 has two active sites to cut both strands of DNA, creating blunt ends (Figure 7).

What happens when the viral DNA is cut?

When the viral DNA is cut, enzymes in the bacterium will naturally attempt to repair it.

Repair mechanisms in the cell are prone to errors, leading to:

Nucleotide additions

Nucleotide deletions

Insertions within the viral gene.

Such errors can render viral genes non-functional, which is advantageous when dealing with bacteriophage infiltration.

If a mutation does not occur after the initial cut, the gRNA will:

Identify the gene again.

Repeat the process until the DNA repair mechanisms induce a mutation that inactivates the virus.

Definitions

Endonuclease: an enzyme that breaks the phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides in a polynucleotide chain

Cas9: an endonuclease that creates a blunt end cut at a site specified by guide RNA (gRNA)

CRISPR: short, clustered repeatsof DNA found in prokaryotes which protect them againstviral invasion

Spacer: short sequences of DNA obtained from invading bacteriophages that are added into the CRISPR sequence

Protospace: a short sequence of DNA extracted from a bacteriophage by Cas1 and Cas2, which has yet to be incorporated into the CRISPR gene

Protospacer Adjecent Motif (PAM): a sequence of two-six nucleotides that is found immediately next to the DNA targeted by Cas9

Guide RNA (gRNA): RNA which has a specific sequence determined by CRISPR to guide Cas9 to a specific site

Blunt End: the result of a straight cut across the double-stranded DNA by an endonuclease resulting in no overhanging nucleotides

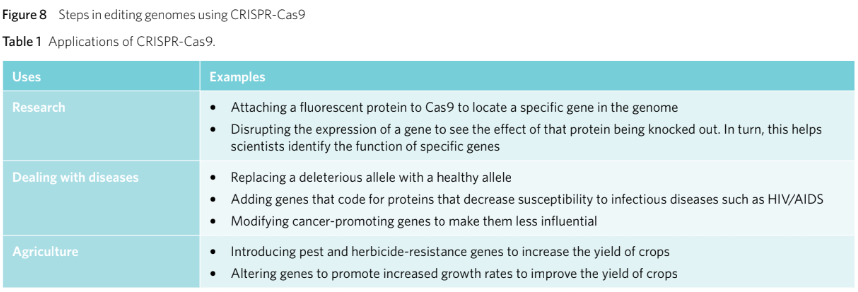

CRISPR-Cas9 in gene editing

Overview: Scientists have been able to adapt the CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit genomes with great precision.

Theory details

The power of CRISPR-Cas9:

Genetic modifications can:

Amend deleterious mutations.

Introduce biologically advantageous alleles to an individual’s genome.

However, many gene therapy techniques:

Lack precision.

May inadvertently insert DNA into the wrong part of the genome, interrupting healthy and functioning genes.

While gene therapy has enormous potential to solve health problems:

It has rarely been used on humans outside of research and clinical trials.

CRISPR-Cas9 has been labelled as the future of genetic engineering:

Potential to increase crop productivity.

Potential to eliminate genetic diseases.

Helps better understand the purpose of specific genes.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system induces genetic changes by:

Cutting DNA at a location specifically chosen by scientists.

Utilizing synthetic sgRNA (single guide RNA) to guide Cas9.

sgRNA characteristics:

Made from a single strand of RNA, unlike gRNA in bacteria.

Functions the same as gRNA when used by scientists as a gene-editing tool.

Cutting DNA with CRISPR-Cas9 creates opportunities for:

Adding, removing, or substituting nucleotides in the selected sequence.

Knocking out, enhancing, or changing the function of a gene.

How to use CRISPR-Cas9 for gene editing

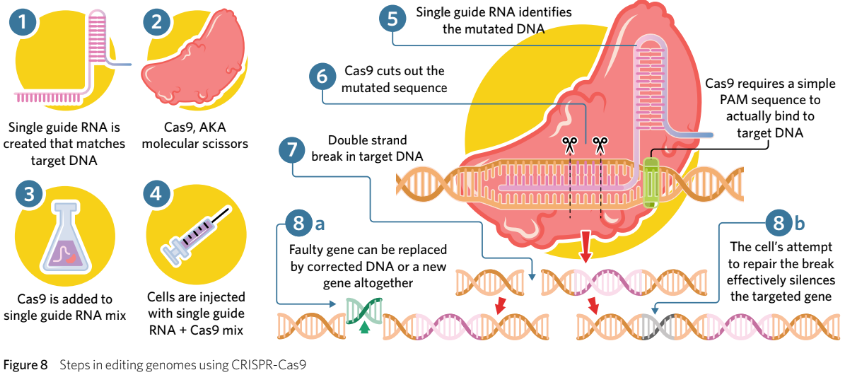

CRISPR-Cas9 is not the only mechanism available for genetic engineering, however, it is currently the most precise and affordable option. To use CRISPR-Cas9 for gene editing, the following steps must be taken (Figure 8):

Synthetic sgRNA is created in a lab that has a complementary spacer to the target DNA that scientists wish to cut.

A Cas9 enzyme is obtained with an appropriate target PAM sequence.

Cas9 and sgRNA are added together in a mixture and bind together to create the CRISPR-Cas9 complex.

The sgRNA-Cas9 mixture is then injected into a specific cell, such as a zygote.

the Cas9 finds the target PAM sequence and checks whether the sgRNA aligns withthe DNA.

Cas9 cuts the selected sequence of DNA.

the DNA has a blunt end cut that the cell will attempt to repair.

When repairing the DNA, the cell may introduce new nucleotides into the DNA at this site. Scientists may inject particular nucleotide sequences into the cell with the hope

that it will ligate into the gap.

Definitions

Virus: a non-cellular, infectious agent composed of genetic material enclosed in a protein coat that requires a host cell to multiple

Bacteriophage: a virus that infects prokaryotic organisms

CRISPR-Cas9: a complex formed between gRNA and Cas9 which can cut a target sequence of DNA. Bacteria use this complex for protection from viruses and scientists have modified it to edit genomes

Genetic Modifications: the manipulation of an organism’s genetic material using biotechnology

Deleterious Mutation: a change in DNA that negatively affects an individual

Gene Therapy: repairing genetic mutations by replacing a defective gene with a healthy one

Single guide RNA (sgRNA): guide RNA utilised by scientists to instruct Cas9 to cut a specific site when using CRISPR-Cas9 in gene editing

Gene Knockout: a technique in gene editing where scientists prevent the expression of a target gene to understand its function in an organism

Limitations of CRISPR-Cas9

CRISPR-Cas9 has great potential for use in medicine and research.

There are many limitations to the technology:

Animal studies show success in eliminating genetic diseases (e.g., muscular dystrophy in mice).

Success in humans has not yet been observed.

Reliable elimination of genetic diseases still requires further research.

CRISPR-Cas9 simply cuts DNA at a chosen site:

Induction of substitution mutations or knocking in new segments requires introduction of nucleotide sequences into the cell.

Successfully taking up sequences by DNA repair machinery can be difficult and inconsistent.

Progress has been slow due to ethical implications:

Genome alteration using CRISPR-Cas9 requires treating embryos before cell differentiation to ensure all cells are altered.

Ethical concerns about respect for the sanctity of human life with embryo research.

It is illegal to implant genetically modified embryos into human females, preventing any allowed development to birth, to mitigate potential harm to mothers and unborn children.

The bioethical concept of non-maleficence discourages causing harm wherever possible.

Non-maleficence may lead individuals to oppose laws against the gestation of genetically modified embryos due to concerns about unforeseen negative consequences on pregnancy.

Conversely, if a couple discovers their foetus has a genetic condition that could be fixed by CRISPR-Cas9, non-maleficence may support the use of this technology to reduce pain for the child or parents.

Other Ethical Concerns:

Safety:

Possibility of off-target cleavages (edits in the wrong place) and mosaics (some cells with edited genomes, others not) make scientists hesitant to use CRISPR outside of research.

Informed Consent:

Scientists cannot obtain consent from embryos for gene editing. If an embryo is born and later has children, these offspring also lack consent for genetic interference.

Inequality:

Concerns exist that only wealthy individuals will afford CRISPR for treating genetic conditions or altering genes.

Discrimination:

CRISPR may pose a threat to those perceived as biologically inferior, while such individuals may not feel the need for 'fixing'.

CRISPR-Cas9 technologies present immense potential and are often viewed as easier and more cost-effective than other gene editing methods.

Despite limitations, CRISPR-Cas9 research has yielded promising results, especially in agriculture.

Theory summary

• CRISPR refers to a series of short, palindromic, clustered repeats of DNA that are separated by spacer DNA. CRISPR is naturally found in prokaryotes, where it plays an important role in defending against bacteriophage invasions.

• CRISPR is transcribed into gRNA, which delivers Cas9 to a specific recognition site.

In bacteria, this recognition site is typically the genetic material of a virus that has invaded

− In genetic engineering, sgRNA is synthetic and complementary to a recognition site that researchers wish to genetically modify

• Cas9 is an enzyme with two active sites which cuts both strands of DNA to create a blunt end cut.

• CRISPR-Cas9 technologies are now being extensively studied, as they offer a precise and potentially affordable pathway to scientific breakthroughs, dealing with diseases, and improving agriculture.

Chapter 4E - Recombination & Transformation

Why Transform Bacteria?

Genetically modifying bacteria to produce human proteins has revolutionised modern medicine and agriculture.

Theory Details

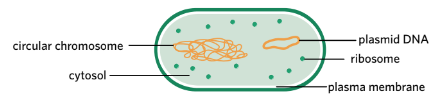

Bacteria are simple prokaryotic organisms that replicate their plasmid DNA independently from their circular chromosome. The number of plasmids in each bacterium varies – one bacterium may have many plasmids whereas another may have none. Bacterial plasmids vary in length and can be anywhere up to 200 kbp.

Bacteria possess independently replicating plasmids.

Humans can genetically modify bacteria to synthesize large amounts of protein.

This process involves editing a plasmid to incorporate a target gene of interest.

Edited plasmids that integrate a target gene are called recombinant plasmids.

Bacteria take up these recombinant plasmids from the environment.

The process of bacteria taking up recombinant plasmids is called bacterial transformation.

Bacterial transformation is a crucial step in the genetic modification process.

Once this has occurred, bacteria can synthesise specific proteins. In this lesson, you will learn about each of these steps involved in genetic modification. Bacterial transformation has had many uses in the medical and food industries, usually enabling cheaper and more efficient methods of production. These include the large-scale production of the following proteins:

• insulin to manages diabetes

• erythropoietin to treat anaemia

• chymosin for cheese production

• interferon to treat some cancers

• growth hormone to manage growth disorders

• hepatitis B surface antigen for use in the hepatitis B vaccine

• alpha-amylase for ethanol and high fructose corn syrup production.

• insulin to regulate blood sugar levels in diabetes patients.

Definitions

Recombinant Plasmid: a circular DNA vector that is ligated to incorporate a gene of interest

Bacterial Transformation: the process by which bacteria take up foreign DNA from their environment. Scientists use this process to introduce recombinant

plasmids into bacteria

Genetic Modification: the manipulation of an organism’s genetic material using biotechnology

Insulin: a hormone secreted by the pancreas to control blood glucose levels

Diabetes: a disease where the body cannot properly produce or respond to insulin

Making a Recombinant Plasmid

Overview

Genetic engineers are often interested in introducing DNA into an organism where it doesn’t naturally occur. A simple way of doing this is to insert foreign DNA into a plasmid that can then be taken up by bacteria. The bacteria will then express the protein encoded by that foreign DNA.

Theory details

Plasmids are excellent cloning vectors because they can self-replicate, are small, can be taken up by bacteria, and it is easy to include antibiotic resistance genes, recognition sites, and expression signals. In order for scientists to create recombinant plasmids, they require a gene of interest, a plasmid vector, a restriction endonuclease, and DNA ligase.

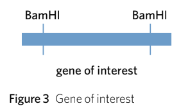

Gene of interest

The gene of interest is a sequence of DNA encoding the protein we wish to produce.

Several ways exist to generate a specific sequence of DNA, but these methods are not covered in depth by VCAA.

The DNA sequence of a human protein is isolated and amplified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) before insertion into a vector.

Bacteria can synthesize an identical protein from the gene of interest, even if it comes from another organism, due to the universality of the genetic code (e.g., CUU codon encodes leucine in all organisms).

The gene of interest must not contain introns prior to insertion because prokaryotic gene expression does not involve RNA processing, unlike eukaryotes.

Bacteria would not be able to process intron segments effectively.

The introns are typically excluded from the gene of interest via two major methods:

• use synthetic DNA - genes are made synthetically in a laboratory using what is called a DNA synthesiser. Introns are not included in the gene when it is made this way.

• use copy DNA (cDNA) - cDNA is made from an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase (RT), which functions to transcribe mRNA backwards into the cDNA. Consequently, cDNA does not contain introns due to the absence of introns in the mRNA being reverse transcribed.

Plasmid vector

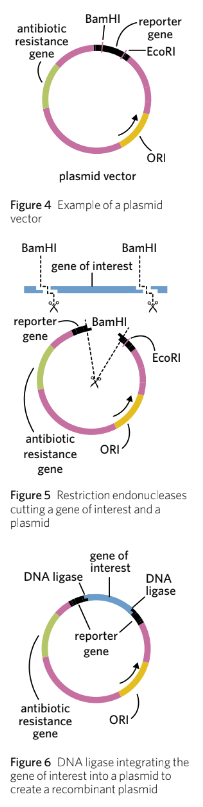

A plasmid vector is selected into which the gene of interest will be inserted. Many different plasmid vectors have been designed by scientists, but most contain the following four important DNA sequences (Figure 4):

• Restriction endonuclease sites – a site on the plasmid that can be recognised and cut by a restriction endonuclease, allowing the gene of interest to be inserted.

• Antibiotic resistance genes – e.g. ampR which confers ampicillin resistance or tetR which confers tetracycline resistance.

• Origin of replication (ORI) – a sequence that signals the start site for DNA replication in bacteria.

• Reporter gene – genes with an easily identifiable phenotype that can be used to identify whether a plasmid has taken up the gene of interest.

Importantly, for a plasmid to be selected it must contain two genes that encode for observable traits, such as antibiotic resistance genes or reporter genes such as gfp, which encodes for a recognisable fluorescent protein. These observable traits are needed to be able to recognise successful plasmid vectors in later steps. In addition, one of these two genes must contain the restriction site of the restriction endonuclease that is to be used.

Restriction endonuclease

The gene of interest and the plasmid are cut with the same restriction endonuclease.

This generates identical sticky ends on either end of the DNA sequence.

Example: BamHI restriction enzyme is used to isolate the gene of interest and create an opening in the plasmid vector.

The BamHI restriction site in the plasmid is located within the reporter gene.

The plasmid contains two genes that encode observable traits.

The overhanging nucleotides of the gene of interest are complementary to the overhanging nucleotides on the plasmid vector, facilitating hydrogen bond formation.

Blunt end restriction enzymes can also be used, but they are less targeted compared to sticky end restriction enzymes, as blunt ends can bond with any other blunt end.

DNA ligase

DNA ligase is added to join the gene of interest to the plasmid vector.

This process forms phosphodiester bonds in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

The result is a circular piece of DNA called a recombinant plasmid.

Not every plasmid will take up the gene of interest; many will ligate back with themselves, termed non-recombinant plasmids.

The procedure creates a mixture of both recombinant and non-recombinant plasmids.

The reporter gene plays a role in distinguishing between recombinant and non-recombinant plasmids.

Bacteria must first undergo transformation for plasmid uptake.

Definitions

Gene of interest: a gene scientists want to be expressed in recombinant bacteria. This gene often encodes a protein we wish to produce in commercial quantities. Also known as the desired gene

Restriction endonuclease: any enzyme that acts like molecular scissors to cut nucleic acid strands at specific recognition sites. Also known as a restriction enzyme

Ligase: an enzyme that joins molecules, including DNA or RNA, together by catalysing the formation of phosphodiester bonds

Vector: a means of introducing foreign DNA into an organism. Plasmids are a popular vector in bacterial transformationgene of interest

Plasmid Vector: a piece of circular DNA that is modified to be an ideal vector for bacterial transformation experiments

Antibiotic Resistance gene: gene which confers antibiotic resistance

Origin of Replication (ORI): a sequence found in prokaryotes that signals the start site of DNA replication

Reporter Gene: gene with an easily identifiable phenotype that can be used to identify whether a plasmid has taken up the gene of interest

Transforming Bacteria

Overview

Many bacteria will naturally take up free-floating DNA from their environment into their cytosol via transformation. Biologists are able to take advantage of this process to make bacteria take up recombinant plasmid

Uptake of recombinant plasmids

The uptake of a recombinant plasmid involves the plasmid being inserted into the cytoplasm of bacteria via bacterial transformation.

Two primary methods for promoting recombinant plasmid uptake are:

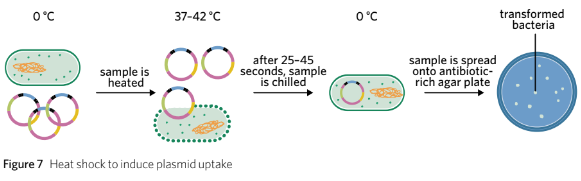

Heat Shock Method:

Bacteria and plasmids are placed in a calcium ion solution on ice.

Positive calcium ions enhance the permeability of the plasma membrane to negatively charged plasmid DNA.

The solution is heated to approximately 37–42 °C for 25–45 seconds, then returned to ice.

This temperature change increases plasma membrane permeability, allowing plasmid vectors to cross the phospholipid bilayer and enter the bacteria’s cytoplasm.

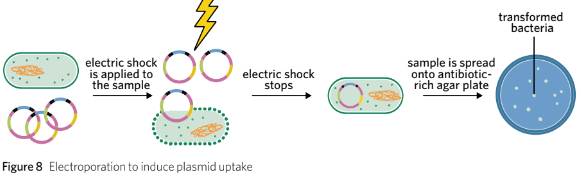

Electroporation:

An electrical current is passed through a solution containing bacteria and plasmids to increase membrane permeability.

Electroporation is a similar process to the heat shock method but instead of heat, an electrical current is passed through a solution containing bacteria and plasmid vectors. The electrical current causes the plasma membrane to become more permeable, allowing plasmid vectors to cross the phospholipid bilayer and enter the bacteria’s cytoplasm (Figure 8).

Antibiotic Selection

To distinguish between transformed and untransformed bacteria, the mixture is cultured onto an antibiotic-rich plate.

Only transformed bacteria contain the gene necessary for antibiotic resistance; untransformed bacteria are killed off.

Each visible colony on the plate indicates a transformation event, where a single bacterium has taken up a plasmid, allowing it to survive and multiply.

Transformed bacteria may take up both recombinant and non-recombinant plasmids, which must be distinguished.

Distinction between recombinant and non-recombinant plasmids is based on the presence of a gene that encodes an observable trait within the plasmid vector.

An example of a reporter gene is gfp, which encodes the green fluorescent protein that fluoresces green under UV light when fully expressed.

In non-recombinant plasmids, the reporter gene is continuous and fully expressed, allowing these bacteria to glow under UV light.

In recombinant plasmids, the reporter gene is interrupted by the gene of interest, leading to non-continuous expression, preventing these bacteria from glowing under UV light.

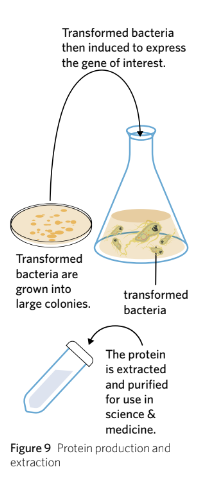

Protein Production & Extraction

The transformed bacteria are cultured and induced to produce the target protein. As the bacteria make lots of different proteins, the protein of interest is extracted and purified (Figure 9).

Definitions

Heat shock: a method that involves rapidly increasing and decreasing the temperature to increase membrane permeability in order to enhance the likelihood of bacterial transformation

Electroporation: a method that involves delivering an electric shock to bacterial membranes to increase their membrane permeability and increase the likelihood of bacterial transformation

Insulin

Overview

Insulin is an important hormone that is responsible for regulating our blood glucose levels. People living with diabetes do not naturally produce or respond to insulin and require it to be administered artificially into their body. Luckily, insulin can be produced by transformed bacteria.

Theory details

Prior to gene cloning techniques:

Porcine (pig) or bovine (cow) insulin was extracted for diabetics.

Extracting insulin required killing many animals.

Animal-derived insulin was less effective for blood glucose regulation compared to human insulin.

Late 1970s:

Human insulin was first produced using bacteria containing recombinant plasmids.

This method is cheaper and more effective than animal extraction.

Insulin's structure:

Has a quaternary structure consisting of two polypeptide chains (alpha and beta subunits).

Requires two different recombinant plasmids to produce insulin: one for each subunit.

Functionality:

Alpha and beta chains must fold individually and be joined by disulphide bridges for proper functionality.

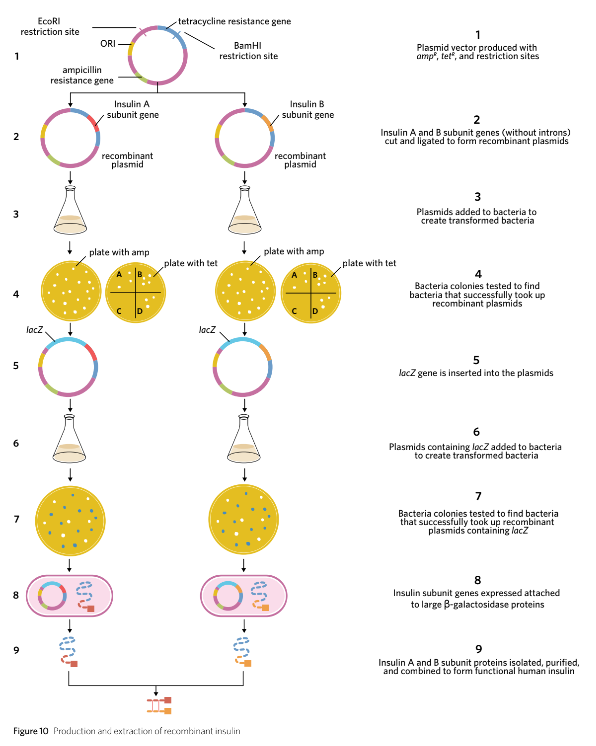

Creating the recombinant plasmid

Prepare plasmid vectors:

Two plasmid vectors are required: one for insulin subunit A and another for insulin subunit B.

Each plasmid includes the ampR gene for ampicillin resistance and the tetR gene for tetracycline resistance.

The tetR gene acts as a reporter gene and contains a specific recognition site for a restriction endonuclease used in the next step.

Cut DNA with restriction endonucleases:

Use EcoRI and BamHI restriction endonucleases to cut both plasmid samples as well as the insulin A and B subunit genes.

The cuts create complementary sticky ends on each piece of DNA, facilitating binding during ligation.

Ensure that the insulin subunit genes do not contain introns, as they were produced in a laboratory setting.

Add an extra codon coding for methionine at the beginning of each insulin gene to facilitate proper protein translation.

Ligate the DNA fragments:

Introduce DNA ligase to join the cut plasmid vectors and insulin subunit genes.

Ligase facilitates the formation of phosphodiester bonds, establishing a continuous sugar-phosphate backbone.

This process results in the creation of two distinct recombinant plasmids, one for each insulin subunit.

Two plasmid vectors were used - one for insulin subunit A and one for insulin subunit B. Using the two restriction endonucleases EcoRI and BamHI, both plasmid samples, the insulin A subunit gene, and the insulin B subunit gene, were all cut to form complementary sticky ends. It is once again important to note that the inserted insulin subunit genes were without introns as they were produced in a laboratory. In addition, the insulin subunit genes were also created with an extra codon coding for methionine at the beginning of the insulin gene. DNA ligase was then used to reestablish the sugar-phosphate backbone and create two different recombinant plasmids.

Creating transformed bacteria

Preparation of E. coli Solution: Plasmids containing the insulin subunit genes and control elements are mixed with E. coli bacteria in a solution.

Incubation: The mixture is incubated to allow some bacteria to take up the recombinant plasmids.

Selection on Ampicillin Plates: - Spread the transformed bacteria onto agar plates containing the antibiotic ampicillin.

Only bacteria that have taken up a plasmid (whether recombinant or non-recombinant that has the resistance gene) will survive and form colonies.

Subsequent Selection with Tetracycline: - Take samples from the colonies grown on ampicillin plates and spread them onto new agar plates containing tetracycline.

Bacteria that are susceptible to tetracycline have taken up recombinant plasmids where the tetR gene has been interrupted.

Identification of Recombinant Bacteria: - Non-recombinant bacteria remain resistant to tetracycline while recombinant bacteria will be susceptible; thus, non-resistant bacteria are identified as containing recombinant plasmids.

Isolation of Recombinant Plasmids: Collect the colonies that show susceptibility to tetracycline.

Insertion of lacZ Gene: - Cut the collected recombinant plasmids open using EcoRI again.

Insert the lacZ gene (minus its stop codon) into these plasmids.

Re-introduction to E. coli: - Add the modified recombinant plasmids containing the lacZ gene to a new solution of E. coli bacteria.

Testing for lacZ Activity: - Spread this new mixture onto agar plates containing ampicillin and X-gal.

ß-galactosidase produced from the lacZ gene converts X-gal from colorless to blue.

Identification of Successful Transformants: - Colonies that turn blue indicate successful incorporation of the recombinant plasmid containing both insulin and lacZ genes, as indicated by the presence of ß-galactosidase.

Purification of Insulin: - The bacteria capable of producing insulin subunit proteins are identified, cultured, and processed for protein extraction.

Protein production and extraction

Incubation of Transformed Bacteria:

Transformed bacteria containing recombinant plasmids are placed in a nutrient-rich growth medium under suitable conditions (e.g., temperature, pH).

These conditions facilitate the exponential reproduction of the bacteria, allowing them to multiply rapidly.

Cell Harvesting:

After sufficient growth, the bacterial cells are collected by centrifugation or filtration to separate them from the growth medium.

Cell Lysis:

The membranes of the harvested bacterial cells are broken down using physical, chemical, or enzymatic methods (e.g., using lysozyme or detergent).

This process releases cellular contents, including proteins such as the insulin subunit and ß-galactosidase fusion proteins, into the solution.

Protein Separation:

The lysate containing the proteins is subjected to purification techniques such as chromatography or precipitation to separate proteins from other cellular debris and components.

Addition of Cyanogen Bromide:

Cyanogen bromide is added to the solution. This compound reacts with the methionine residue attached at the start of the insulin gene.

The reaction cleaves the bond between the methionine and the insulin subunit, effectively separating the insulin subunit from the ß-galactosidase fusion protein.

Isolation of the Insulin Subunit:

After cleavage, techniques such as centrifugation or additional chromatography are used to isolate the freed insulin subunit from any remaining fusion proteins or other impurities.

Formation of Functional Insulin:

The now-separated insulin subunits (alpha and beta chains) are mixed together under conditions that promote the formation of disulfide bonds.

This mixing allows the subunits to fold correctly and bond together, resulting in the formation of functional human insulin.

The two insulin chains were then mixed together, which allowed the connecting disulphide bonds to form and create functional human insulin.

Definitions

Fusion protein: a protein made when separate genes have been joined and are transcribed and translated together

Theory Summary

Bacterial transformation involves the following steps:

Extraction of target genes

Formation of recombinant plasmids

Plasmid uptake by bacteria

To distinguish transformed from non-transformed bacteria:

An antibiotic resistance gene is included in the plasmid vector

This gene is expressed only by successfully transformed bacteria

Transformed bacteria can be isolated

The proteins they produce, such as human insulin, can be purified.