Unit 1

Jan 8 - Types of Molecular Interactions

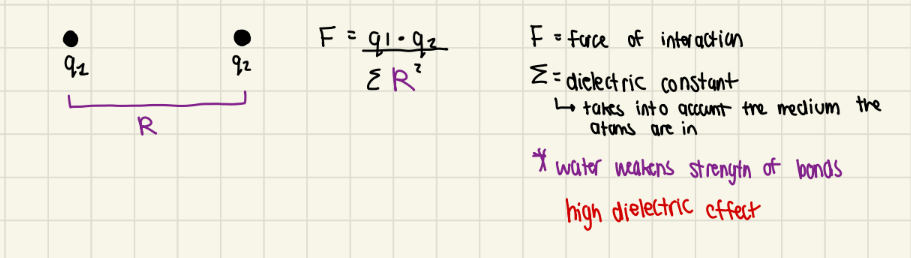

ionic - interaction of 2 charged atoms based on coulombs law

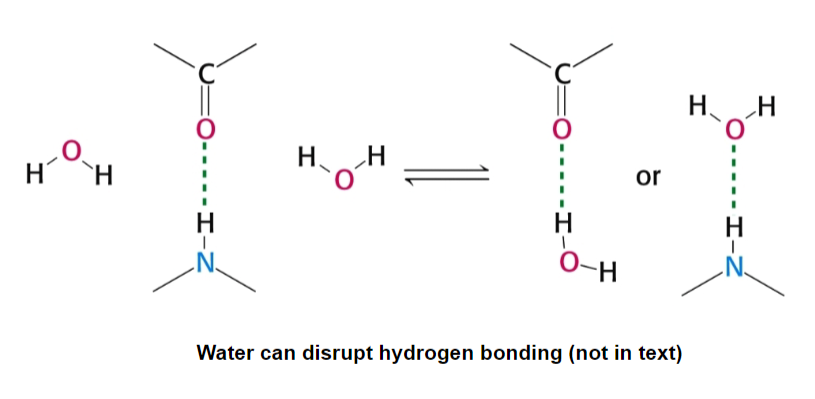

hydrogen bonds - unequal sharing of a hydrogen atom; a hydrogen atom that is partly shared by 2 electronegative atoms

the hydrogen donor is electronegative and tends to pull electrons away from the hydrogen, the result is:

hydrogen donor: delta -

H is covalently bonded to

H: delta +

hydrogen acceptor: delta -

both are usually O2 or N2, sometimes Suflur

is also electronegative and develops a delta -

needs a lone pair of electrons

how a hydrogen bond is formed: the delta + charged H is attracted to the delta negative acceptor and hydrogen bond is formed

H-bonds are weak 4-13 kJ/mole and longer 1.5-2.6 A than covalent bonds

Van Der Waals Interactions - temporary dipoles; attraction of any 2 molecules

at any given time, the charge distribution around an atom is not symmetric

result: this asymmetry causes complimentary asymmetric on other atoms, causing them to be attracted to each other

has smallest energies of 2-4 kJ/mole

attraction inc until the electron clouds start to overlap and repel

contact distance is the distance maximal attraction of 2 atoms

Hydrophobic Interaction - almost all biochemical reactions occur in water

water has a big impact on these reactions and interactions

structure: has a bent shape, making the molecule polar and capable of forming multiple H-bonds

result: water is very cohesive (can form hydrogen bonds with each other); a hydrogen-bonding machine

water is an excellent solvent for polar or charged molecules

hydrophilic: soluble in water

hydrophobic: insoluble in water

amphipathic: hydrophilic + hydrophobic groups

water can weaken electrostatic interactions by competing for their charge (or partial charge)

water reduces electrostatic interactions by 80x (high dielectric constant)

result: serious consequences for biological systems, water often needs to be excluded/manipulated to allow various electrostatic reactions to occur

water is a double-edged sword: we need it to dissolve, but it interferes with electrostatic interactions

Jan 10 - Laws of Thermodynamics

All biological events are governed by a series of physical laws of thermodynamics

I. The total energy of a system (matter in a defines space) and its surroundings is constant; cannot be created or destroyed, can only change form

ex. burning wood or dropping a ball off a roof

Enthalpy (H): the heat content of our system

II. The total energy of a system and its surroundings always increases for a spontaneous process

entropy (S) = randomness

system or universe increase in entropy for a reaction to go forward

ex. goes from ordered system to a more disordered one

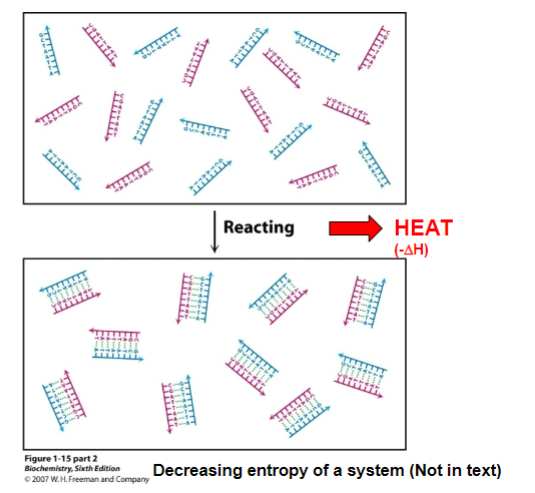

Things can become more ordered

entropy can be decreased locally in the formation of ordered structures ONLY if the entropy of the universe is increased by an equal or greater amount

entropy decreases in system (2 molecules going to 1 molecule) but heat is released causing the entropy around the system (ex. the universe) to increase

TLDR: reaction releases heat, causing entropy of the universe to increase, which is greater than the decrease of entropy in the system

we can exist only if we make the universe more disordered

How to Measure Spontaneity

ΔG = ΔHsys - TΔSsys

T = temp in K

ΔG is gibbs free energy measured in KJ/mole

Spontaneity = how likely a reaction or process will occur

doesn’t define how fast a reaction is, only if the reaction will occur

ΔG < 0 = the reaction is spontaneous

ΔG > 0 + the reaction is non-spontaneous

Enthalpy/Entropy

Affect on ΔG

ΔH < 0 (ex. releasing heat)

ΔG becomes more negative and the reaction becomes more spontaneous

ΔS > 0 (ex. reaction becomes more disordered)

ΔG becomes more negative and the reaction becomes more spontaneous

Why you want to know ΔG → reactions needs to be spontaneous to occur in the cell (ΔG = no reaction)

Jan 10 - Entropy & The Hydrophobic Effect

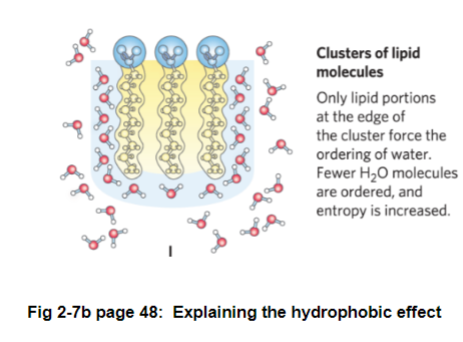

Hydrophobic molecules cluster together since the entropy is more favorable

hydrophobic molecule entropy decreases

water entropy increases - more hydrogen bonds with water, more ordered

Fig 2-7b page 48: when a non-polar molecule is added to water, the water molecules are forced into a cage around the hydrophobic molecule

result: lowers entropy since water is becoming ordered

when 2 non-polar molecules come together, fewer water molecules are needed to form the cage around the non-polar molecules

result: entropy increases; favors non-polar molecules to cluster together (not a direct force pulling the 2 molecules together)

Jan 10 - Ph and Buffers

The concentration of hydrogen ions within biological systems is critical

Why? Most biomolecules (not all) act as weak acids or bases (ex. their functional groups can be ionized)

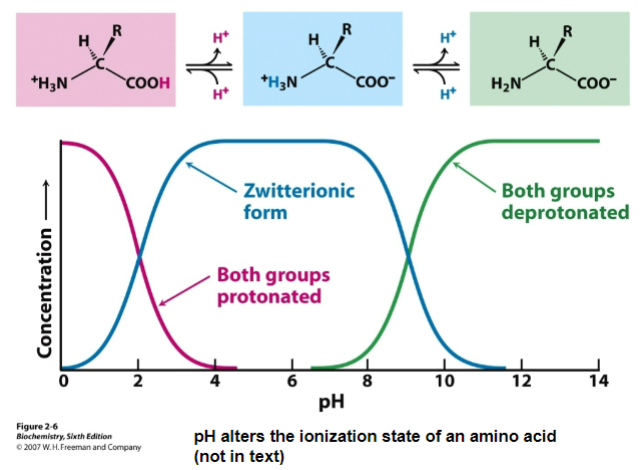

Figure 2-6: amino acid and nucleotide charge changes with plot

changing pH may change the way a molecule behaves since it can affect its ionization state

molecule behavior depends on ionization state

[H] is measured as pH

pH = -log[H]

scale of 0-14

0 = strongly acidic

14 = strongly basic

How do we maintain a pH of a cell (7.2-7.4)? Weak acids can act as buffer

weak acid = an acid that is not completely ionized in solution

acid - gives up protons

base - proton acceptor

HA ←→ A^- + H^+

pKA = -logKa

we can calculate the pH of any solution of a weak acid if we know the molar ratio of a conjugate base to acid and pKa → Henderson Hasselbalch Equation

pH = pKa + log[A]/[HA]

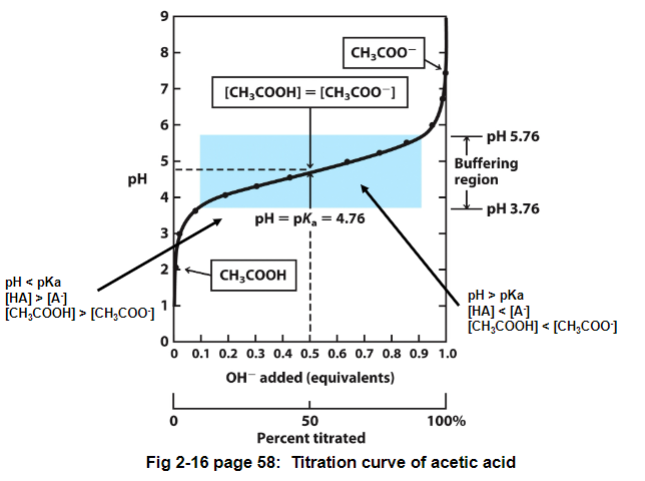

if we titrate a weak acid (ex. acetic acid) with a strong base (NaOH) we can see the following:

pH = pKA → [HA] = [A]

pH < pKa → [HA] > [A] → more acid than conjugate base

pH > pKa → [HA] < [A] → conjugate base is more dominant form

Fig 2-16: there is a region where the pH doesn’t change very much even though a large amount of acid (or base) are being added

buffering region: a mixture of a weak acid and a conjugate base in a 1:1 ratio

function: resists changes in pH because both forms are present and can either soak up or release a proton

pH = pKa here

the buffering region is usually +/- pH unit from pKa unit

ex. if pKa is 4.76, pH is 3.76

buffers fail when there is only the acid or conjugate base present

you want the buffer to have a pKa = 7

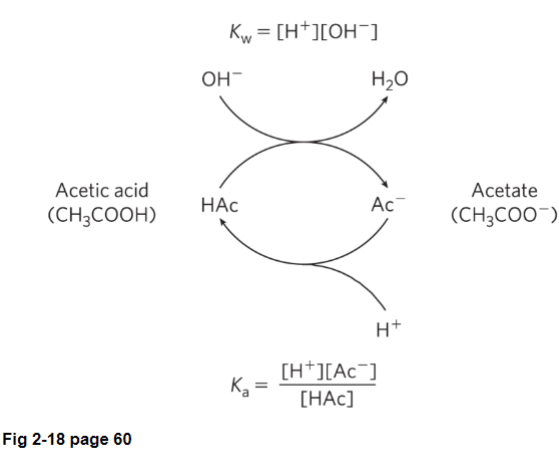

Fig 2-18: buffer gives away proton, turning into the conjugate base (acetate)

if HCI is added, the pH will drop (increasing [H])

pH will go down slowly if you add both acetic acid and acetate since acetate will soak up the proton, turning it into acetic acid

Types of Buffers

Bicarbonate (more complicated)

CO2 (dissolved) + H2O ←→ H2CO3 (carbonic acid) ←→ H + HCO3 (bicarbonate)

approximate pKa of 6.1, would buffer from 5-7

Phosphate

H2PO4^- ←→ H + HPO4^-2

pKa of 7.1, buffering rage 6.2 - 8.2

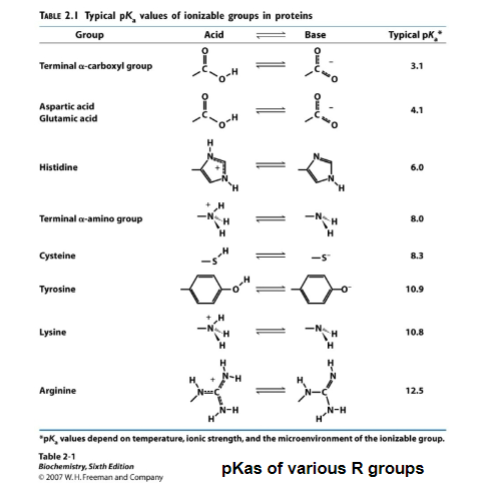

Histidine and Cysteine

amino acids

Histidine pKa = 6; Cysteine pKa = 8

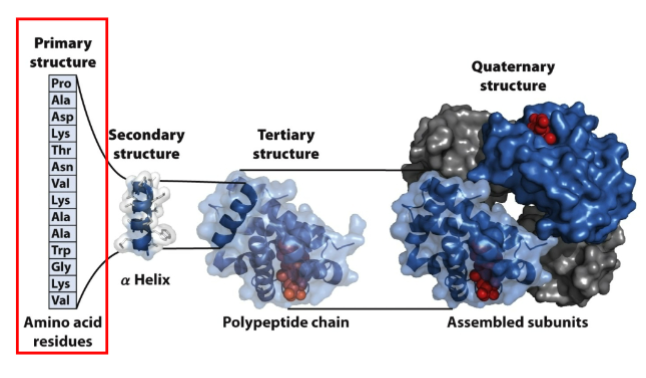

Jan 13 - Protein and Amino Acid Structure

protein: linear polymer built of amino acids

structure: final shape depends on its sequence of a.a

a.a contain a variety of functional groups, allowing for massive diversity

proteins can interact with each other or molecules to form complexes

proteins can be flexible or rigid

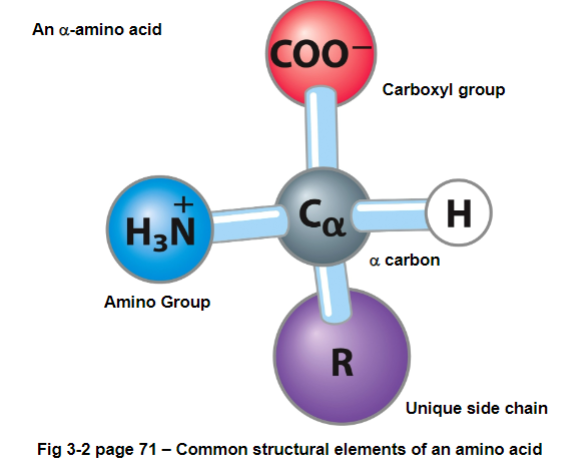

amino acid: the “ultimate lego set”

Structure:

alpha carbon

carboxylic acid/ carboxyl group (COOH/COO-)

the form that exists depends on pH

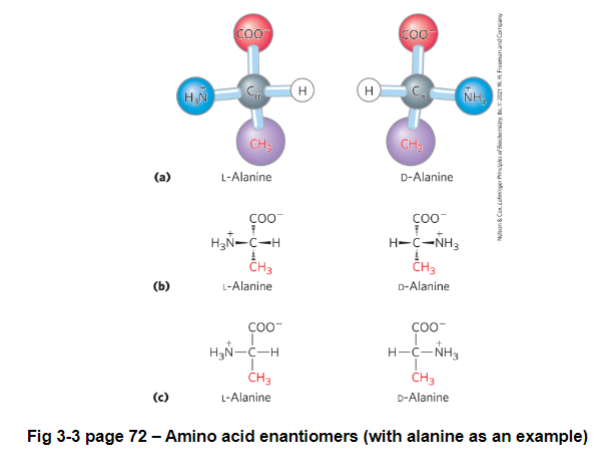

the carbon is chiral: an atom that has 4 different functional groups; not superimposable on its mirror image

thus there are 2 enantiomers of each amino acid, except for glycine (R group is hydrogen)

enantiomer: a pair of molecules each with one or more chiral center that are mirror images of each other

hydrogen

unique R side-chain

FIG 3-2: amino refers to NH3 group, acid refers to carboxyl group - all attached to an alpha carbon

Determining L or D

carboxyl group is above central carbon, and R group is below

L amino acid = if amino group (NH3) is on left to alpha carbon

D amino acid = if amino group (NH3) is on right to alpha carbon

In biological systems only the L-amino acids exist (with very few exceptions) in proteins and living systems

furthermore almost all L-amino acids are in the S-configuration

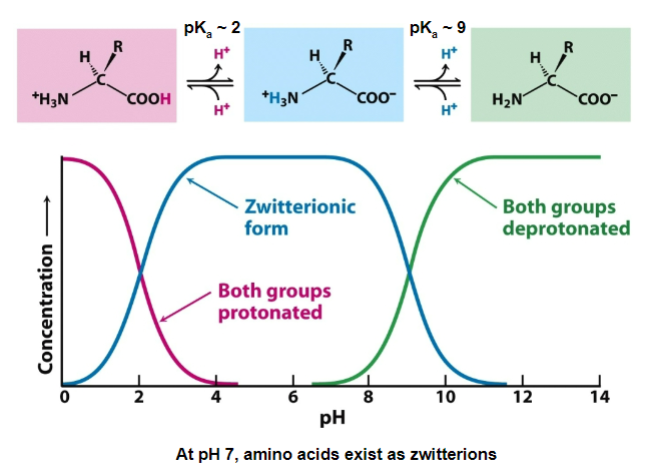

Ionization of amino acids

all amino acids have 2 ionizing group (carboxyl and amino group), often 3 (R-group)

carboxyl pKa = 2

pH 0-2 - COOH dominates

pH 2 - 14 - COO- dominates

amino group pKa = 9

0 - 9 - NH3+ dominates

Hence, at pH 7 amino acids exist as zwitterions: ions with both positive and negative charges

Types of Amino Acids

basic and acidic amino acids are often found on the surface of proteins (interact with water and away from the hydrophobic amino acids)

you can vary the amino acid by changing the side-chain (R-side chain)

there are 20 key amino acids and these (or slight modifications are used in all living things

you have to know all 20 amino acids (draw them), their structures, names, and abbreviations

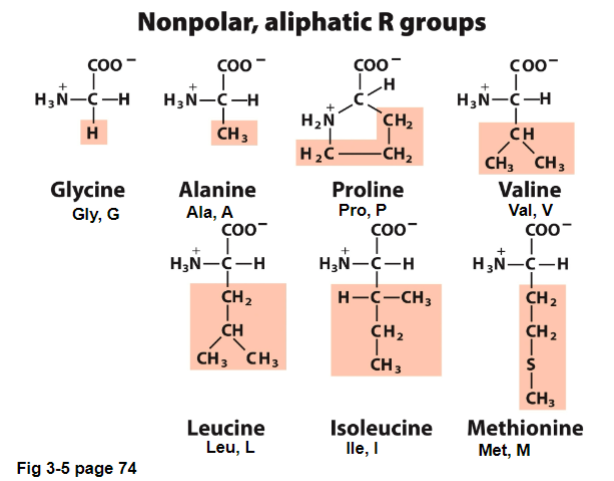

Jan 15 - I. Nonpolar, Aliphatic R groups

Non-polar, aliphatic: all are hydrophobic and will tend to cluster together

different sized and shaped R-groups allow for close packing

usually found in the center of a protein, away from the water

usually not reactive

aliphatic: compounds with an open chain structure (alkane)

Types of Polar, uncharged R groups | Characteristics | How to remember |

Glycine (Gly,G) |

| |

Alanine (Ala, A) |

|

|

Valine (Val, V) |

|

|

Leucine (Leu, L) |

|

|

Isoleucine (Ile, I) |

|

|

Methionine (Met, M) |

|

|

Proline (Pro, P) |

|

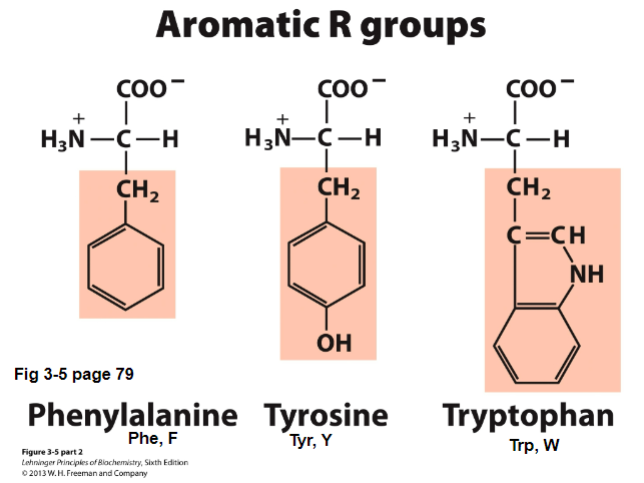

II. Aromatic R-groups

Aromatic Amino Acids: contain aromatic rings (ex. phenyl rings)

participate in hydrophobic interactions

usually found in the core of proteins

Types of Aromatic R-groups | Characteristics | How to remember |

Phenylalanine (Phe, F) |

|

|

Tyrosine (Tyr, Y) |

|

|

Tryptophan (Trp, W) |

|

|

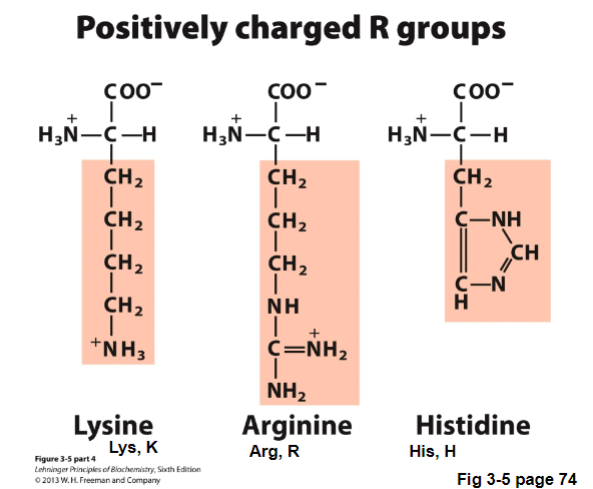

III. Basic Amino Acids - Positively Charged R Groups

Basic Amino Acids (positively charged, high pKas)

lysine and arginine are both positively charged at pH 7 (pKas > 10)

Mea culpa: my grievous fault; the imidazole of His is aromatic, but we don’t classify it as aromatic

Types of Basic Amino Acids - Positively Charged R Groups | Characteristics | How to remember |

Lysine (Lys, K) |

| |

Arginine (Arg, R) |

|

|

Histidine (His, H) |

|

|

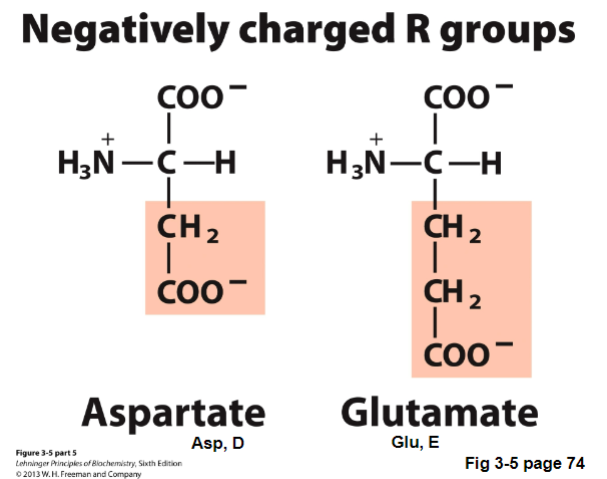

Jan 17 - IV. Acidic Amino Acids - Negatively Charged

Acidic Amino Acids - negatively charged

contain carboxyl groups as R groups

negatively charged at pH 7 (pKas < 4)

Types of Acidic Amino Acids - Negatively Charged | Characteristics | How to remember |

aspartate (Asp, D) |

|

|

glutamate (Glu, E) |

|

|

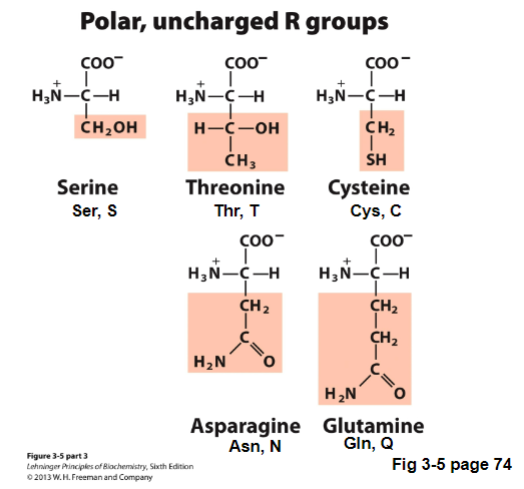

V. Polar, Uncharged R groups

not charged at pH 7

can H-bond, more hydrophilic

Types of Polar, uncharged R groups | Characteristics | How to remember |

serine (Ser, S) |

| |

threonin (Thr, T) |

| |

cysteine (Cys, C) |

| |

Asparagine (Asn, N) |

|

|

Glutamine (Gln, Q) |

|

|

note: the pKa for an R group of an amino acid can change depending on the environment (see page 2 of problem set 2)

dont have to remember pKa, just now the conjugate base and acid form

Protein Structure

Jan 20 - I. Primary Structure

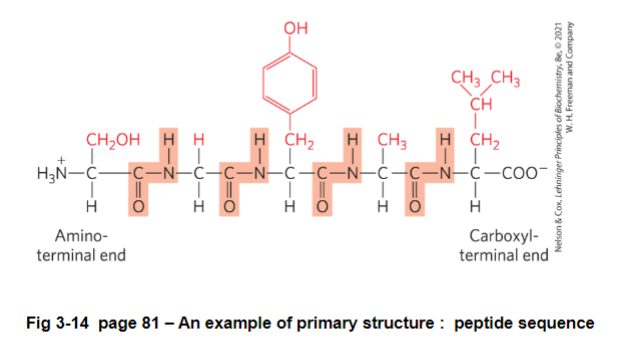

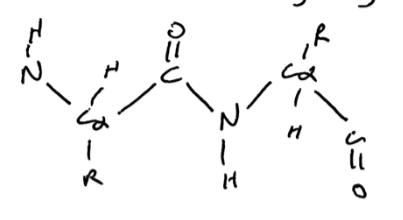

I. Primary Structure (1 degree) - linear sequence of amino acids linked by peptide bonds to form a polypeptide

peptide bond - linkage of alpha-carboxyl linked to the other alpha-amino group of another amino acid with the loss of water

not energetically favorable, but once formed stable

delta G to break the peptide bond is more favorable (rather be single amino acids) - the activation energy to break a peptide bond is very high

polypeptide - a series of amino acid residues linked by peptide bond

structure

have polarity

not referring to charge, the ends are different (the end that has a free amino - NH3 group)

free amino group should always be on left, free carboxyl group is on right

residue - an amino acid unit in a polypeptide

contain a backbone which repeats (NCC)(NCC) with variable side chains

the backbone is hydrophilic

carbonyl and amino group can H-bond, except proline which has limited H-bonding ability

molecular weights of proteins are expressed in Daltons or more commonly Kilodaltons (kDa)

1 Da = mass of hydrogen atom = 1g/mole

each protein has a unique primary amino acid sequence

primary sequence is encoded in the DNA

knowing the primary amino acid sequence allows us to determine the

determine shape - 3D shape of a protein depends on primary sequence

determine function

understand disease

understand evolutionary history

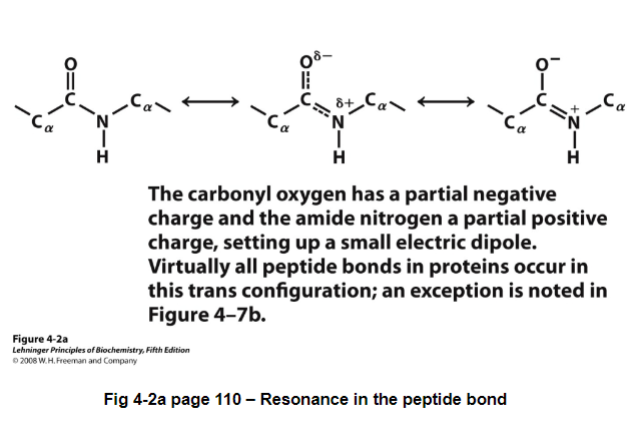

polypeptides are flexible but conformationally restrained

what does this mean? the peptide bond has double bond characteristics due to resonance between the peptide bond and the carbonyl

result:

the peptide bond is planar. This in turn locks a series of atoms into a plane

no rotation about the peptide bond

since peptide bond acts like a double bond, the peptide bond could be in cis or trans orientation

cis = same direction

trans = pointing in diff directions

due to steric hindrance, all peptide bonds are in trans (except for x-pro peptide bond where both cis and trans occur)

fig 4-2: are all in one plane; can’t rotate around the peptide bond

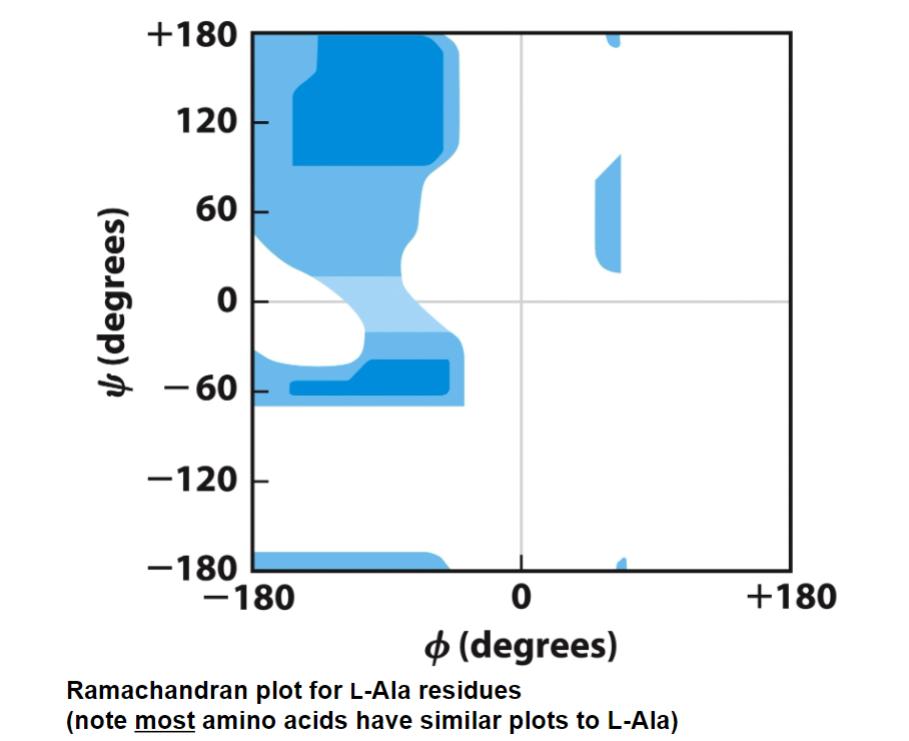

this partly explains the conformationally restrained part, but what about flexibility?

the bond between N-Calpha and C=O-C-alpha are free to rotate

result: provides flexibility, allowing the backbone to fold in many ways

we measure the amount of rotation about the bond as the dihedral angle (torsion angle)

ranges from - 180 to + 180

N - Calpha dihedral angle = phi = φ

C=O-C-alpha dihedral angle = psi = Ψ

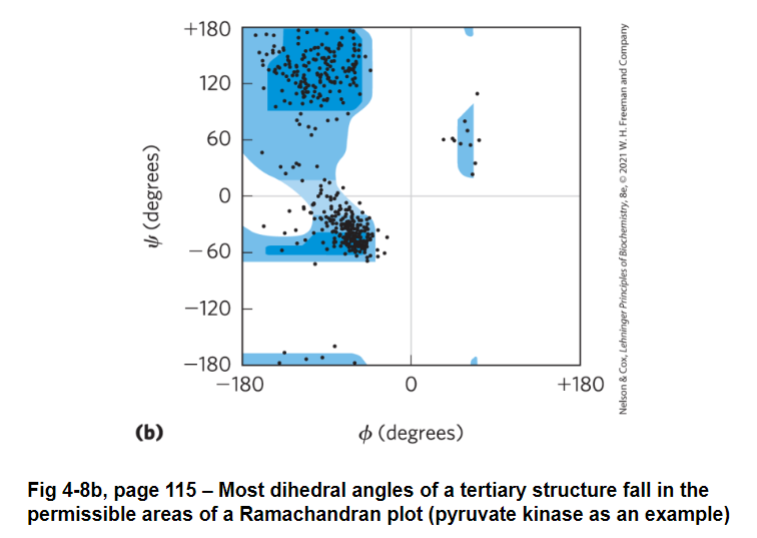

not all combinations of phi and si are allowed due to steric hinderance, limiting the number of structures a protein can adopt

the combination of phi and si that are possible are shown in a Ramachandran plot

ex. lysine, has H as an R-group, less clashing so more blue

ex. proline, has an R-group ring and covalently bonded to nitrogen - phi are the ones restrained since ring will block it from doing so

Ramachandran plot

darker shade = very favorable

lighter shade = less favorable, but possible

white shade = not permitted

most amino acids have similar plots to L-Ala

note: ¾ of all dihedral angles are not permitted

bringing this all together

large molecules that can freely rotate among many bonds will assume random coils (no defined final structure; a mix of different structures)

because proteins have a series of limitations on what orientation they adopt

1st limitation: double bond characteristic, planar peptide bonds

2cnd limitation: the dihedral angles, phi and si

thus, they can often spontaneously fold into a single structure

FIG 3-14: should be written as H3N - S - G - Y - A - L - Coo^-

Point Mutations

K 614 P

K = original amino acid

614 = location in primary sequence from the N terminal end

P = new amino acid

ex. describe E6V mutation in the beta-glonin protein

E = glutamine - acid/negatively charged charge

V = valine - r-group is non-polar aliphatic

went from negatively charged to a hydrophobic group

each hemoglobin protein consists of 2 alpha-globin and 2 beta-globin subunits

creates a new hydrophobic patch on the surface of T-state hemoglobin and allows to self-polymerize

rods are inflexible, causing sickle cell anemia

sickle cells go through capillary beds, doesn’t twist and flex and hurts our capillaries (don’t need to know, just know the effect of a singe point mutation)

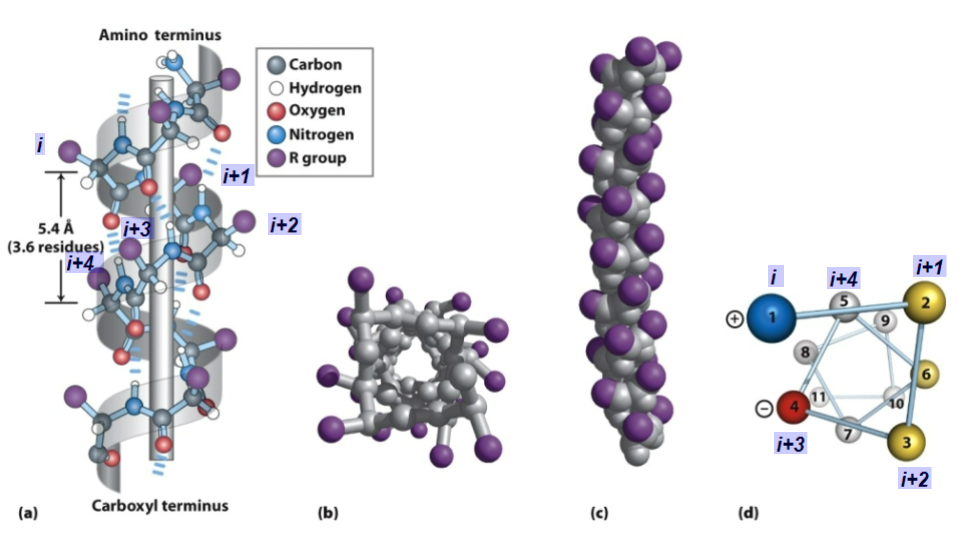

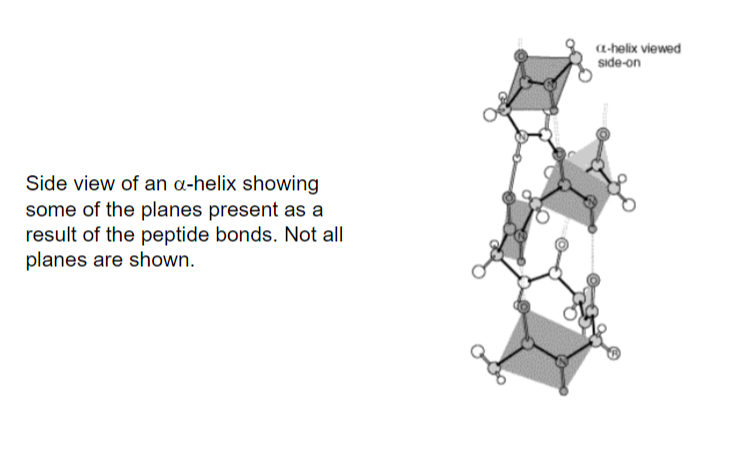

Jan 22 - II. Secondary Structure - Alpha Helix

II. Secondary Structure - spatial arrangement for amino acid residues in a polypeptide that are relatively close to each other in linear sequence

alpha helices and beta strands/sheets - the common types of secondary structures

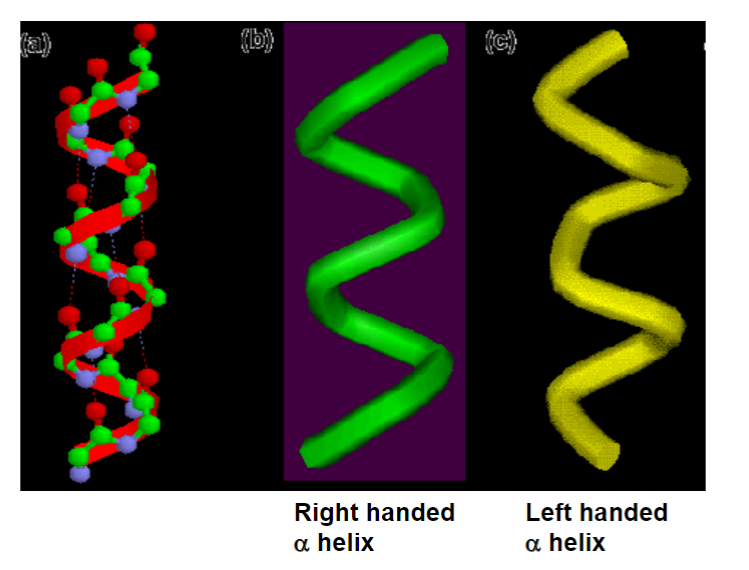

alpha helix - a polypeptide backbone forms the inner part of a right handed helix, with the side chains sticking outwards

structure

the helix is stabilized by intrachain hydrogen bonds between the NH and C=O groups of the backbone

intrachain = hydrogen bonds are within the backbone

R-groups are almost perpendicular to the axis of the helix

has ideal dihedral angles of phi - 60 and psi -45

the C=O of residue i forms an H-bond with the N-H or residue i + 4 (ex. 4 residues further towards C-terminus) - see diagram below

the helix is almost always right handed

left handed and right handed alpha helix are not the same (not superimposable)

all the NH and C=O in the backbone are H-bonded, except the ends

each amino acid residue in the helix increases the helix length by 1.5 angstroms

helix rises by 1.5/# of amino acids

r-groups of i, i +1 and i+2 point in different directions

r-groups of i, i +3 and i + 4 point in similar directions

important because it aids in an ampithatic molecule

left handed helices are permitted but rare (not as stable)

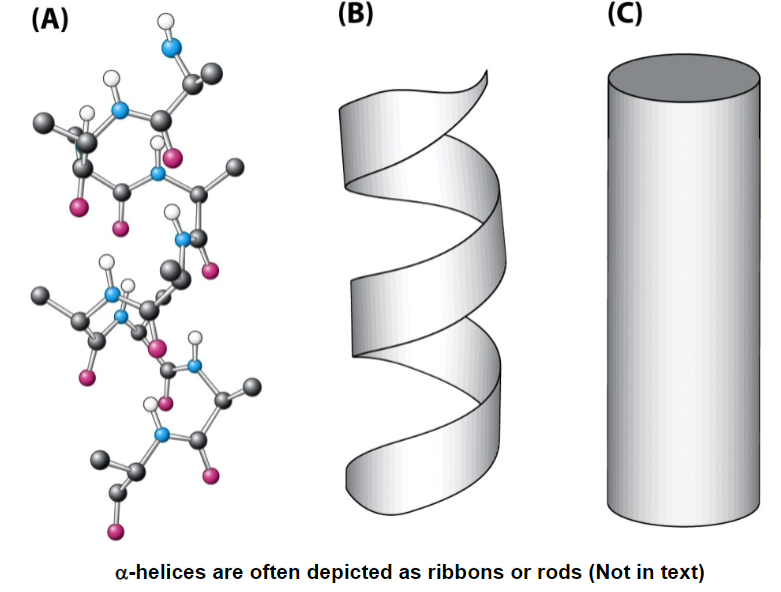

alpha helices are show as twisted ribbons or rods

alpha helical content of a protein can vary

some proteins have no alpha helices

some proteins are just alpha helices

usually alpha helices are less than 45 angstroms

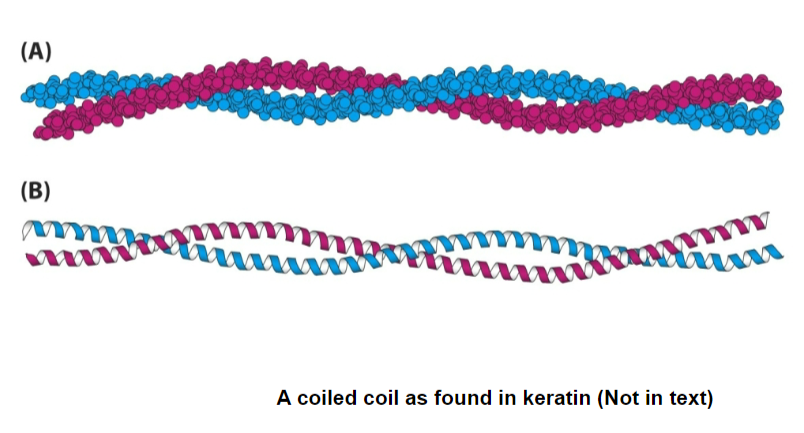

2 alpha helices can intertwine into coiled coils (ex. our hair)

alpha helices are a series of planes that are coiling due to double bond characteristics of peptide bonds

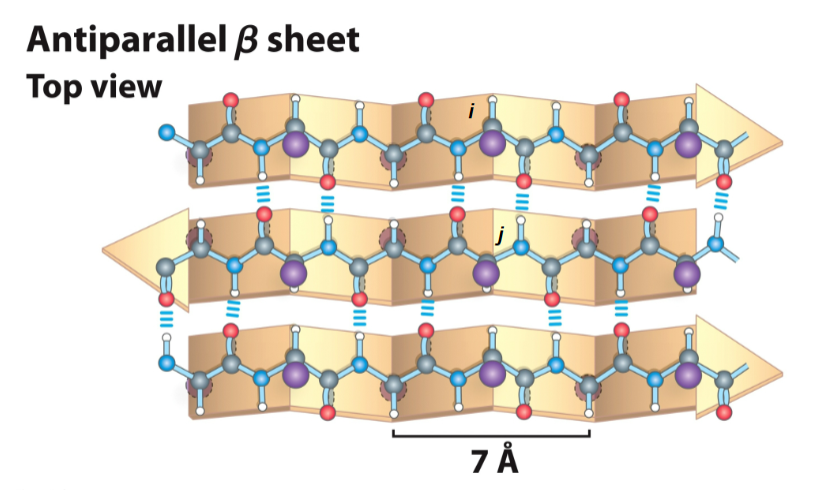

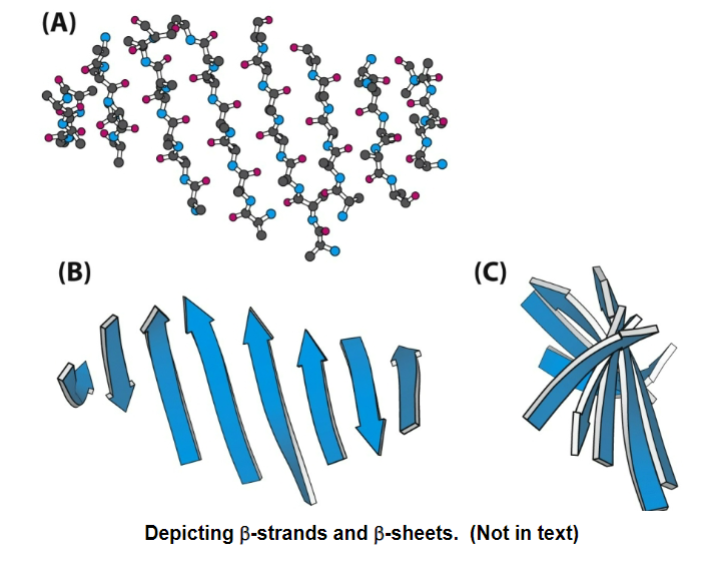

beta-pleated sheets - two or more beta-strands (usually a polypeptide strands from the same molecule) associated as stacks on chains in an extended zigzag form

stabilized by interstrand hydrogen bonds

beta strands are the components that make up a beta sheet

has little zigzags or pleats (each pleat is the plane of a peptide bond)

for an antiparallel beta-sheet

each amino acid extends the beta strand by 3.5 A (more spread out than an alpha-helix)

r-groups are adjacent of adjacent residues point in opposite directions perpendicular to the plane of the strand or sheet

the strands are organized into beta-sheets

strands run in opposite directions, the N-H and C=O of a single residue i on one beta-strand h-bonds to the single residue j on the other beta-stran opposite to it

has ideal dihedral angles of phi - 139 and psi + 135

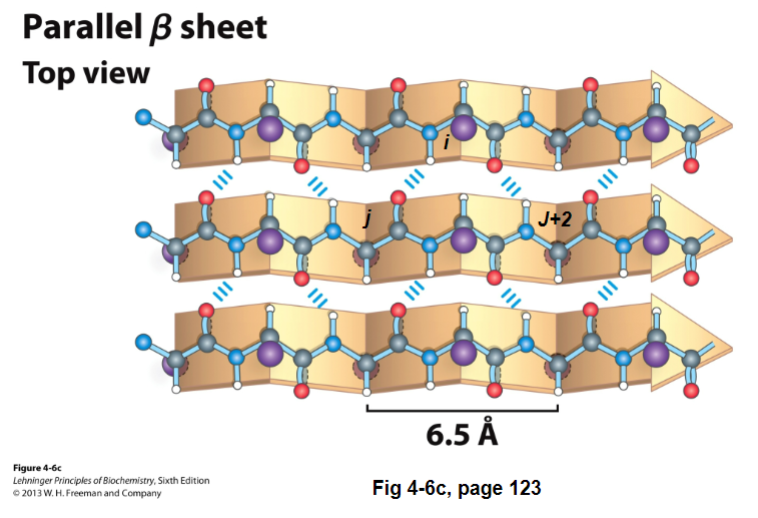

B-sheets can also be parallel. It’s like an antiparallel B-sheet, except:

instead of doing straight down H-bond, it does 2 reaches (shortens length of beta strand + causes dihedral angle to be twisted)

each residue in the beta strand only extends the B-strand by 3.25 A

has ideal dihedral angles of -119 phi and +113 psi

the N-H of residue i on one B-strand H-bonds to residues j C=O in the other strand

C=O of residue in i in the first strand H-bonds to j + 2 N-H in the second strand

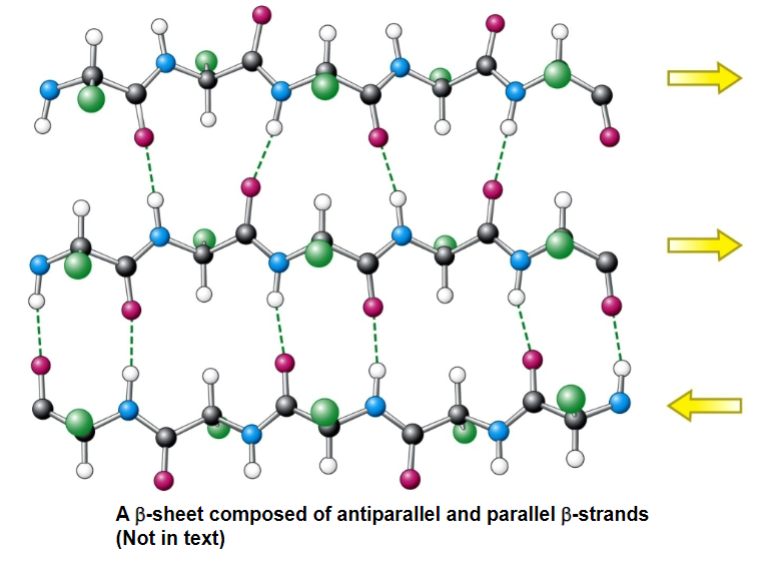

Mixed B-sheets (both parallel and antiparallel)

B-strands are depicted as broad arrows pointing towards the C-terminal end

the distance between B-strands in primary amino acid sequence can be small or large

beta-strands can be short or long

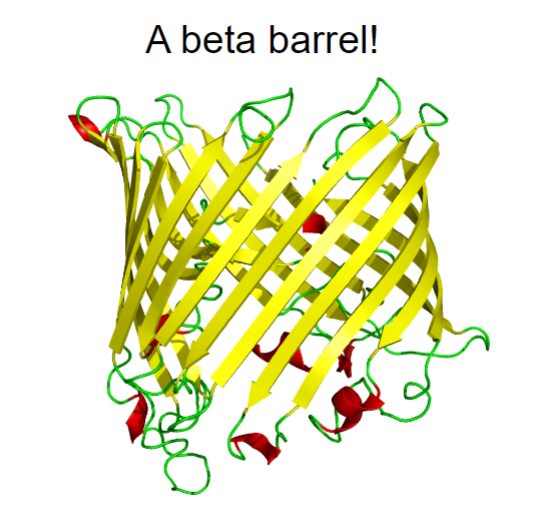

beta-sheets can be flat or twisted

it can even twist back on itself to form a beta-barrel

when drawing out a polypeptide backbone, draw the backbone as a zigzag

forces us to draw it as trans

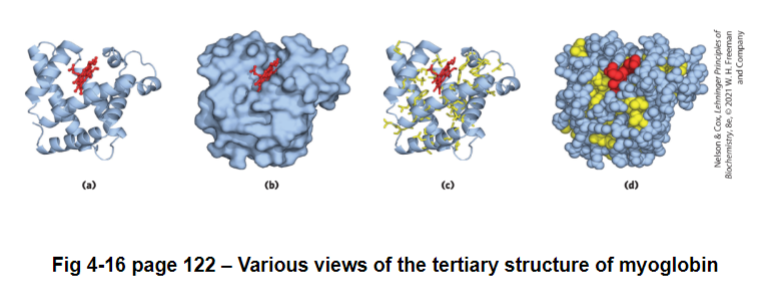

III. Tertiary Structure

Tertiary Structure - the spatial arrangement of amino acid residues that are far apart from each other in linear sequence as well as the pattern of disulfide bonds

BIG MONEY = the 3D structure

each protein tertiary structure is different

tertiary structure is limited to a single polypeptide that folded into a structure

ex. myoglobin

O2 storage protein in mammalian muscles

single polypeptide chain of 153 amino acids

contains a heme group (iron in a protophyrin ring) where the O2 binds to

70% of the chain is in alpha helices (8 helices)

most of the rest are in loops and turns

the core of the protein is almost exclusively composed of hydrophobic residues (except for a his which is needed by the heme)

the surface is composed of more polar/charged residues (and some non-polar)

quick note about myoglobin: binds O2 with high affinity and only releases if when [O2] is really low

why would you wanna know the structure of myoglobin? structure helps us understand function

helps us identify possible places for drug binding

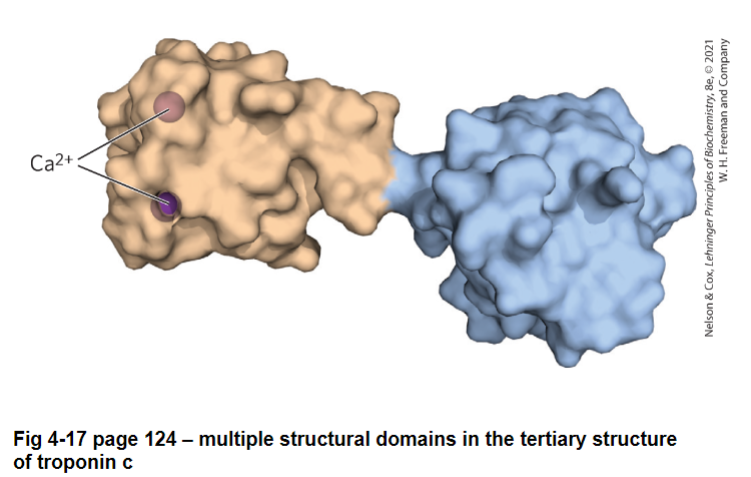

some proteins have multiple compact structures called structural domains linked by flexible sections of the polypeptide (often with no defined structure)

no defined structure = structure is moving around

in most tertiary structures, the dihedral angles for each residues fall into permissible areas of a Ramachandran plot

jan 27 lecture

IV. Quaternary Structure

Quaternary structure: the spatial arrangement of multiple folded subunits (folded polypeptides) and the nature of their interactions along with the disulfide bonds between subunits

some proteins are composed of more than one folded polypeptide chains (subunits)

homomers - the subunits can be identical

heteromers - when the subunits are different

some proteins must be multimers in order to function

protomer - the base unit in a quaternary structure

usually repetitive

usually (not always) monomeric in nature but the structure is not the same as the monomer

protomer is what it looks like in the final structure

fig 2-22 pg 128

ex. hemoglobin

the O2 transporter in mammals

composed of 4 subunits

2 alpha subunits (alpha-globins)

2 beta subunits (beta-globins)

will cover in much more detail later, but it is the interactions between the subunits that are critical for function

hemoglobin cannot function unless it is a tetramer

the protomer for hemoglobin is an alpha-beta dimer

ex. minute virus of mice

9 UPI 2 subunits of 51 UP2 subunits to form an isohedral capsid with just enough room to fit the viral DNA

Protein Folding

even with limitations on the backbone, there are trillions of possible structures a polypeptide could adopt and it would take forever for a protein to try every single structure

however, most proteins spontaneously fold into just one structure in seconds

up until a few years ago, we couldn’t predict a protein’s tertiary structure based off of primary sequence, but now AI programs such as Alphafold2 or rosettafold can!

we do know that folding is driven by thermodynamics

ex. finding the most stable complex (most negative delta G)

note: the difference in free energy between folded and unfolded is small (20-60 kJ per mole)

this is mostly (but not all) driven by entropy (ex. the hydrophobic residues are excluded from water in the core, while hydrophillic residues are on the surface)

backbone of a polypeptide is polar, when it folds, some parts of the backbone is in the core (not favorable).

in order to bury the polar backbone of a polypeptide in the core, it needs to H-bond

many alpha-helices and beta-sheets are amphipathic (one side is hydrophobic, the other is hydrophilic)

unpaired charged or polar group in the hydrophobic core tend to destabilize the structure

Q: can a portion of a primary sequence define a secondary structure?

A: yes and no

certain amino acid residues are more likely or less likely to be found in a stabilized (or destabilized) alpha-helices and beta-strands/sheets

table 4-2 - proline and glycine are alpha-helix wreckers, and to a lesser extend beta strand wreckers

proline has the ring, dihedral angle is limited and can’t twist into the optimal angle for an alpha helix

proline has limited h-bond capabilities since it doesn’t have N-H in its backbone (has N-R instead)

glycine has a hydrogen in its r-group

however, experiments have shown that the exact same portion of sequence in 2 different proteins can adopt 2 different secondary structures

thus we cant always determine the secondary structure by looking at a portion of primary sequence

the overall teritiary structure influences secondary structure

what else do we know?

folding tends to be an all or non process

usually you’re folded or you’re not

it is cooperative

ie. as one portion of the protein folds (ex. beta sheet) it will influence how another portion folds

thus, we don’t have to sample every structure FIG 4-26 pg 131

however, there is usually many possible pathways, so we often depict folding as a free-energy funnel FIG 2-27 pg 132

in a proteins unfolded state, there are many possible structures with high free energy, but as those species fold the free energy decreases until you reach the folded state

the farther you go into folding, there are more limitations to the types of structures you can get\

there are multiple folding routes to get you to the final structure

jan 29

not all proteins have a single 3D structure

some proteins only fold into a single structure when they bind something

some proteins are in equilibrium between 2 structures

determining structure of intact proteins (big deal)

x-ray crystallography

use x-ray to measure e- density

how the structure of myoglobin; hemoglobin were determined

nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

measures the location of nuclei

cryo-electron microscopy

uses a beam of e- to visualize a frozen protein

post-translational modifications (after protein synthesis)

phosphorylation - attachment of phosphate group, usually to the OH of an R-group

commonly phosphorylated residues: Ser, Thr, Tyr

activates or inactivates a protein by adding a negative charge

glycosylation - attachment of a sugar or carbohydrate to an amino acid residue (usually, Asn, Thr, Ser)

surface labelling

most proteins on the cell surface are glycosylated

hydroxylation - adds an OH (usually proline)

result: becomes more polar

fibre stabilization

carboxylation - adds a carboxyl group (usually to glu)

important in clotting

acetylation - addition of an acetyl group to an NH3 (amino) - (ex. lysine)

(insert pic of the acetyl group)

most proteins are cleaved or trimmed after synthesis

this could activate or inactivate them

ex. fibrinogen → cut → fibrin (forms clot)

multiple proteins can be formed from a single long polypeptide

result: multiple mature protein

ex. viruses like to do this

Enzyme Thermodynamics & Kinetics

enzyme - biological macromolecule (usually protein) that acts as a catalyst for biochemical reactions

“work horses of the cell”

catalyst - chemical that increases the rate of a reaction without being consumed

Thus, enzymes speed up reactions

enzymes are very specific, they will only catalyze on specific set of reactions

papein: enzymes that cleaves peptide bonds in a polypeptide

trypsin: only cleaves peptide bonds on the carboxyl side of lys and arg

thrombin: only cleaves peptide bonds only between and arginine and glycine

specificity is based on a series of weak interactions between the substrate and the enzyme, specifically in the active site

dont want too many interactions

the shape of the enzyme determines specificity and function

active site: region of the enzyme that binds the substrate

it contains the residues that directly participate in the reaction

characteristics of active site:

they are clefts (aka dimples) in the enzyme made up of residues from all over the primary sequence

take up a small volume of the enzyme

water is usually excluded or manipulated from the active site

the substrate is bound to the active site by a series of weak interactions

thus, the substrate and the enzyme must be partly complimentary, otherwise the substrate can’t bind and catalysis cannot occur

can occur by

lock and key

active site is a complimentary match to the substrate (rare)

induced fit

binding of the substrate causes the active site to assume a matching shape

jan 31

the hyperbolic curve = equilibrium

enzymes do not alter the final equilibrium of products to reactants (see slide)

enzymes do not alter delta G of reaction, they obey the laws of thermodynamic

ex. they can’t change the spontaneity of a reaction if delta g reaction is positive, it is non-spontaneous and adding enzymes will not change that (fig 1-29 pg 26)

enzymes do speed up the rate of a reaction

how do enzymes do this?

enzymes accelerate reactions by decreasing the activation energy (delta g double dagger) by facilitating the formation of the transition state (X double dagger)

imagine a substrate being converted to product (S → P)

in order to form products, the substrate goes through a transition state (x double dagger), the transition state has the highest G in the reaction and the lowest concentration

the energy needed to get x double dagger is known as the activation energy (delta g double dagger)

usually the activation energy (g double dagger S → P =) (insert picture of formula

activation energy from S → P

activation energy P → S

the activation energy controls the reaction rate

only a fraction of S will have enough energy to form the transition state (x double dagger)

note: the activation energy is not part of the overall delta g of reaction calculations because the energy put in is returned when the transition state is converted to products

fig 6-3 page 181

for S+ E ←→ES ←→ EP←→ E + P

enzymes interact with the transition state such that the activation energy is lowered

therefore, the reaction speeds up as as greater fraction of S has the energy to reach the transition state (X double dagger)

where does the energy come from to lower the activation energy?

comes from the enzyme binding and stabilizing the transition state (x double dagger)

the active site of an enzyme is perfectly complimentary to the transition state (x double dagger)

we call the energy stabilizing the transition state in an enzyme the binding energy (delta Gb)

delta Gb = delta delta G (change in activation energy) = delta g ++ - delta g ++ catalyzed

the energy is derived from the non-covalent interactions between the enzyme and the transition state

END OF MATERIAL FOR MIDTERM

Knowt

Knowt