Chapter 3: Interdependence and the Gains from Trade

Interdependence

- We rely on other people to provide us with goods and services.

- Interdependence is only possible due to Trade.

^^Why do people Trade?^^

- Suppose an economy only has two goods: meat and potatoes. There are also only two producers: Ruby, a cattle rancher, and Frank, a potato farmer.

- Trading goods would allow Ruby and Frank a greater variety of goods.

- By trading, people would not need to be self-sufficient: Ruby would not have to eat meat all the time, and Frank would also not have to eat potatoes for every meal. They could both enjoy a meal of meat and potatoes.

- Trading also allows Ruby and Frank to specialize.

- Suppose the land on Ruby’s cattle is not well suited for potatoes, while Frank is not skilled at raising cattle.

- By trading, Frank and Ruby can each benefit by specializing in what their environment and skills are suited for, and then trading it with another person.

What if one producer is better at producing both goods? Is there still a reason to trade?

Suppose that Ruby is better at raising cattle and producing potatoes than Frank. Is there still a reason for her to trade with Frank?

%%Production Possibilities%%

- Suppose that Frank and Ruby work 8 hours a day each and they can spend this time growing potatoes, raising cattle, or a combination of the two.

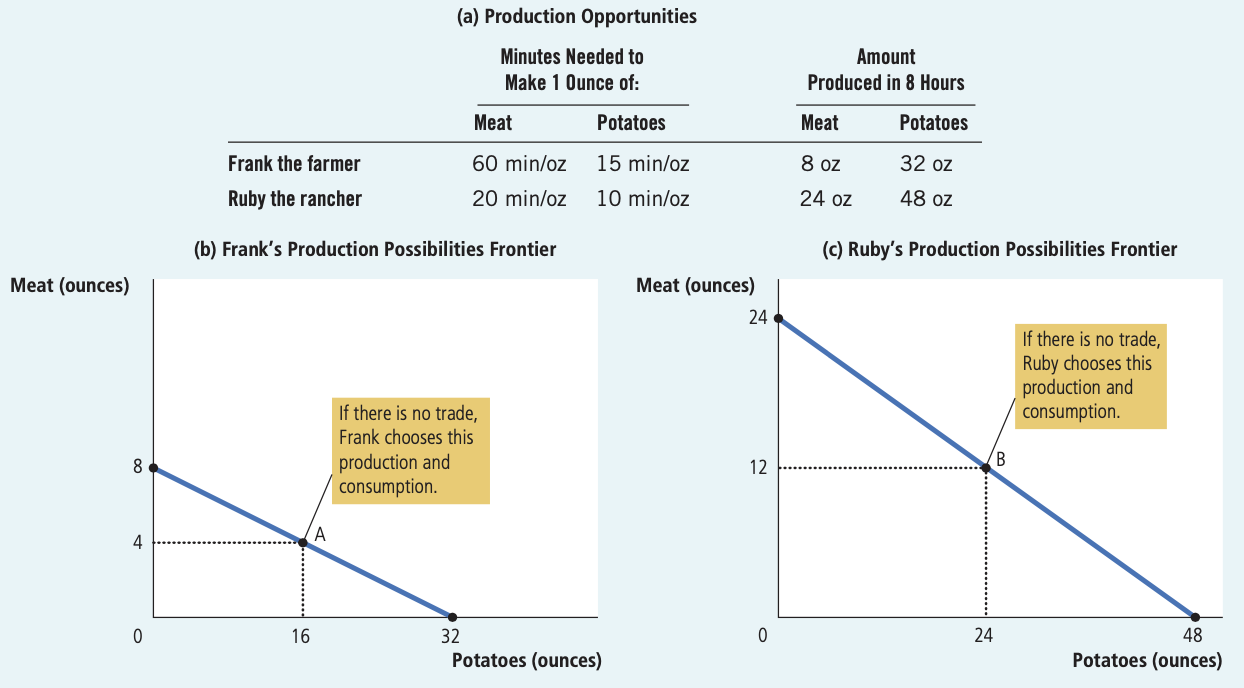

- Figure 1 shows the Production Possibilities Frontiers of producing each good.

- Frank:

- In 8 hours, he can produce either 8 ounces of meat or 32 ounces of potatoes. He can also divide his time equally between the two activities. If he spends 4 hours on each, he can produce 4 ounces of meat and 16 ounces of potatoes.

- This is seen in Panel (b) which represents Frank’s Production Possibilities Frontier.

- Ruby:

- In 8 hours, she can produce either 24 ounces of meat or 48 ounces of potatoes. She can also divide her time equally between the two activities. If she spends 4 hours on each, he can produce 12 ounces of meat and 24 ounces of potatoes.

- This is seen in Panel (c) which represents Ruby’s Production Possibilities Frontier.

- If Frank and Ruby choose to remain self-sufficient rather than trade with one another, then they can only consume what they produce.

- The Production Possibilities Frontiers show the trade-offs that Frank and Ruby face, but they do not tell us which they will actually choose to do.

- To determine their choices, we need to figure out the tastes of Frank and Ruby. We can assume that this will be the combination in Points A and B in Figure 1.

- Frank will produce and consume 4 ounces of meat and 16 ounces of potatoes.

- Ruby will produce and consume 12 ounces of meat and 24 ounces of potatoes.

%%Specialization and Trade%%

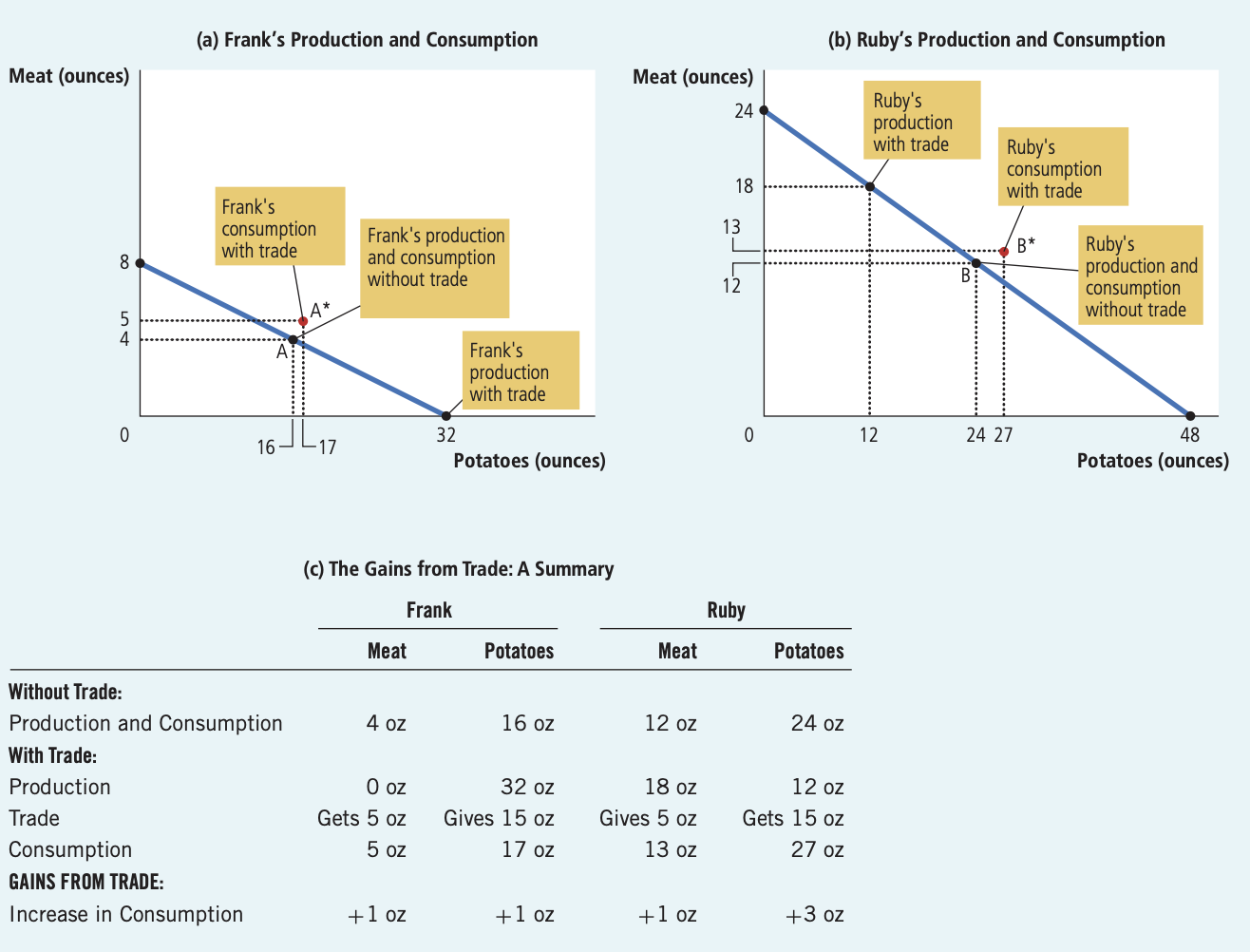

- If Frank specializes in producing potatoes,

- He can devote 8 hours a day to produce 32 ounces of potatoes.

- He can then trade 15 ounces of potato to Ruby, who gives him 5 ounces of meat in return.

- In the end, Frank will have more of both goods.

- Frank will be able to enjoy 17 ounces of potatoes. This is more than what he was producing before when he was self-sufficient, which was only 16 ounces of potatoes a day.

- Frank will now also have 5 ounces of meat, which is more than what he was making before, which was only 4 ounces of meat a day.

- If Ruby specializes producing meat,

- Ruby can now spend more time raising cattle. She can devote 6 hours to raising cattle and only 2 hours for growing potatoes. This will allow her to produce 18 ounces of meat and 12 ounces of potatoes.

- Ruby then trades Frank 5 ounces of meat in exchange for 15 ounces of potatoes.

- In the end, Ruby will have more of both goods.

- Ruby will end up with 13 ounces of meat, which is more than what she was making before, which was only 12 ounces of meat.

- She will also have 27 ounces of potatoes, instead of the 24 ounces she was making before.

- To summarize, trade allows Frank and Ruby to attain a combination of goods that would be impossible without trade. It allows them to consume more goods without working more hours a day.

- In Panel (a), Frank gets to consume more goods at Point A* than at Point A.

- Similarly, in Panel (b), Ruby gets to consume at a higher Point B* than at Point B.

^^Absolute Advantage^^

- Absolute Advantage → The ability to produce a good using fewer inputs than another person

- Economists use this term when comparing the productivity of one producer to that of another.

- In the example above, Ruby has an absolute advantage in both meat and potato production because she requires less time than Frank to produce a unit of either good.

^^Opportunity Cost^^

Opportunity Cost → Whatever must be given up in order to obtain an item.

In the example above, Frank and Ruby only spend a limited time working. Thus, the time spent producing one good takes away from the time that could be spent producing another good. This is the trade-off they face.

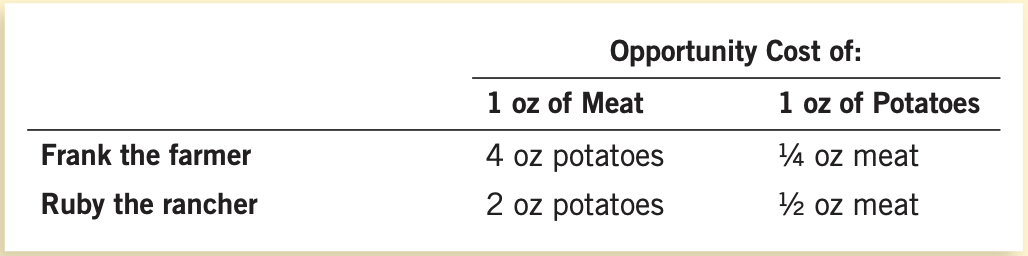

- Ruby’s Opportunity Cost.

- Ruby needs 10 minutes to produce an ounce of potatoes and 20 minutes to produce an ounce of meat.

- Thus, Ruby’s opportunity cost of producing 1 ounce of potatoes is 1/2 ounce of meat. Moreover, 1 ounce of meat costs Ruby 2 ounces of potatoes.

- Frank’s Opportunity Cost

- Frank needs 15 minutes to produce an ounce of potatoes and 60 minutes to produce an ounce of meat.

- Thus, Frank’s opportunity cost of producing 1 ounce of potatoes is 1/4 ounce of meat. Moreover, 1 ounce of meat costs Frank 4 potatoes.

^^Comparative Advantage^^

- Comparative Advantage → The ability to produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another producer

- The producer who gives up less of other goods to produce Good X has the smaller opportunity cost of Good X. Thus, this producer has the comparative advantage on Good X.

- In the example above,

- Frank has a lower opportunity cost of producing potatoes than Ruby. Thus, he has a comparative advantage is potato production.

- An ounce of potatoes only costs Frank 1/4 ounce of meat, while it costs Ruby 1/2 ounce of meat.

- Conversely, Ruby has a lower opportunity cost of producing mea than Frank. Thus, she has a comparative advantage in meat production.

- An ounce of meat only costs Ruby 2 ounces of potatoes, while it costs Frank 4 ounces of potatoes.

^^Comparative Advantage and Trade^^

- When each person specializes in producing the good they have a comparative advantage on, total production increases.

- In the example above, Frank now spends more time producing potatoes and Ruby spends more time producing meat.

- As a result, total potato production rose from 40 to 44 ounces, while total meat production rose from 16 to 18 ounces.

- Moreover, people can get bargains in trade.

- Each person can benefit from trade by obtaining a good at a price lower than their opportunity cost of that good.

- With trade, Frank receives 5 ounces of meat in exchange for 15 ounces of potatoes. In other words, Frank buys an ounce of meat for the 3 ounces of potatoes.

- This is lower than his opportunity cost for producing an ounce of meat, which is 4 potatoes.

- Similarly, with trade, Ruby buys 15 ounces of potatoes in exchange for 5 ounces of meat. Thus, Ruby buys an ounce of potatoes for 1/3 ounce of meat.

- This is lower than her opportunity cost of an ounce of potatoes, which is 1/2 ounce of meat.

- Frank and Ruby should therefore specialize in the goods in which they have a comparative advantage and trade with the other producer.

- Trade can benefit everyone in society because it allows people to specialize in activities in which they have a comparative advantage.

^^The Price of the Trade^^

- The general rule for the price at which trade takes place → For both parties to gain from trade, the price at which they trade at must lie between the two opportunity costs.

- In the example, Frank and Ruby agreed to trade at a rate of 3 ounces of potatoes for 1 ounce of meat.

- This price is between Ruby’s opportunity cost (2 ounces of potatoes per ounce of meat) and Frank’s opportunity cost (4 ounces of potatoes per ounce of meat).

- If the price of trade does not lie between the two opportunity costs, the two parties would have no incentive to specialize and trade.