Bio 301 - Ch. 2 Book Notes

Chapter 2 - Observing the Microbial Cell

fluorescence microscopy captures single molecules within a living cell

the fluorophores can label specific kinds of DNA or proteins

electron microscopy explores the cell’s interior

cryo-electron microscopy reveals the cells the 3D & models the shape of viruses

Example of how the technology has advanced since Leeuwenhoek’s first invention

spiral-shaped methane oxidizing bacterium were isolated in a peat bog in northern Russia

these bacteria are significant for curbing the release of methane from the archaea that produce it

these bacteria were visualized as a whole by phase-contrast microscopy

phase contrast utilizes the wave property of light to bend “out of sync” at the edge between a microbe and its surrounding medium to generate high contrast

electron transmission microscopy

the sample is sliced into very thin sections, stained with electron-dense metal atoms and bombarded with a beam of electrons

upon viewing the specimen, the electron beam reveals layers of membranes stacked like pancakes

these intracellular membranes are packed with proteins that transfer electrons from methane into oxygen

much of the methane is trapped in the cell’s biomass which prevents an escape of a greenhouse gas into the atmosphere

resolution of objects by our eyes

animals’ eyes observe an object by focusing its image on a retina packed with light-absorbing photoreceptor cells

the image appears sharp if the eye’s lens and cornea bend all the light rays from each point of the object to converge at one point on the retina

in the human eye, the finest resolution of two separate points is perceived by the fovea, the portion of the retina where the photoreceptors are packed at the highest density

the foveal photoreceptors are cone cells which detect primary colors and finely resolved detail

the distance between two foveal cones limits our resolution to 100-200 um

our eyes can detect a large population of microbes

examples include: a spot of mold or a cloudy tube of bacteria

observing these examples means the eye can detect the presence of mold or bacteria but it cannot resolve distinct cells

magnification is needed to resolve microbial cells individually to their natural shapes

as the distance increases between points of detail, our eyes can now resolve the object’s shape as a magnified image

microbial size & shape

eukaryotic microbes have a range of cell sizes to which a light microscope can resolve intracellular compartments such as the nucleus and vacuoles

protists show complex shapes and appendages

example includes an ameba from a freshwater ecosystem that has a large nucleus and pseudopods to engulf prey

another example includes Trypanosoma brucei which is an insect-borne blood parasite that causes African sleeping sickness; a nucleus and flagellum can be observed under a light microscope

certain shapes of bacteria are common to many taxonomic groups

both bacteria & archaea form similarly shaped rods, bacilli and cocci

it can be noted rods and spherical shapes evolved independently within different taxa

another shape distinction is a spirochete in which species of this shape cause diseases such as Lyme borreliosis and syphilis; the spiral form is maintained by internal axial filaments, flagella, and an outer sheath

an unrelated spiral form is known as spirillum which is a wide, rigid spiral cell that is similar to a rod-shaped bacillus

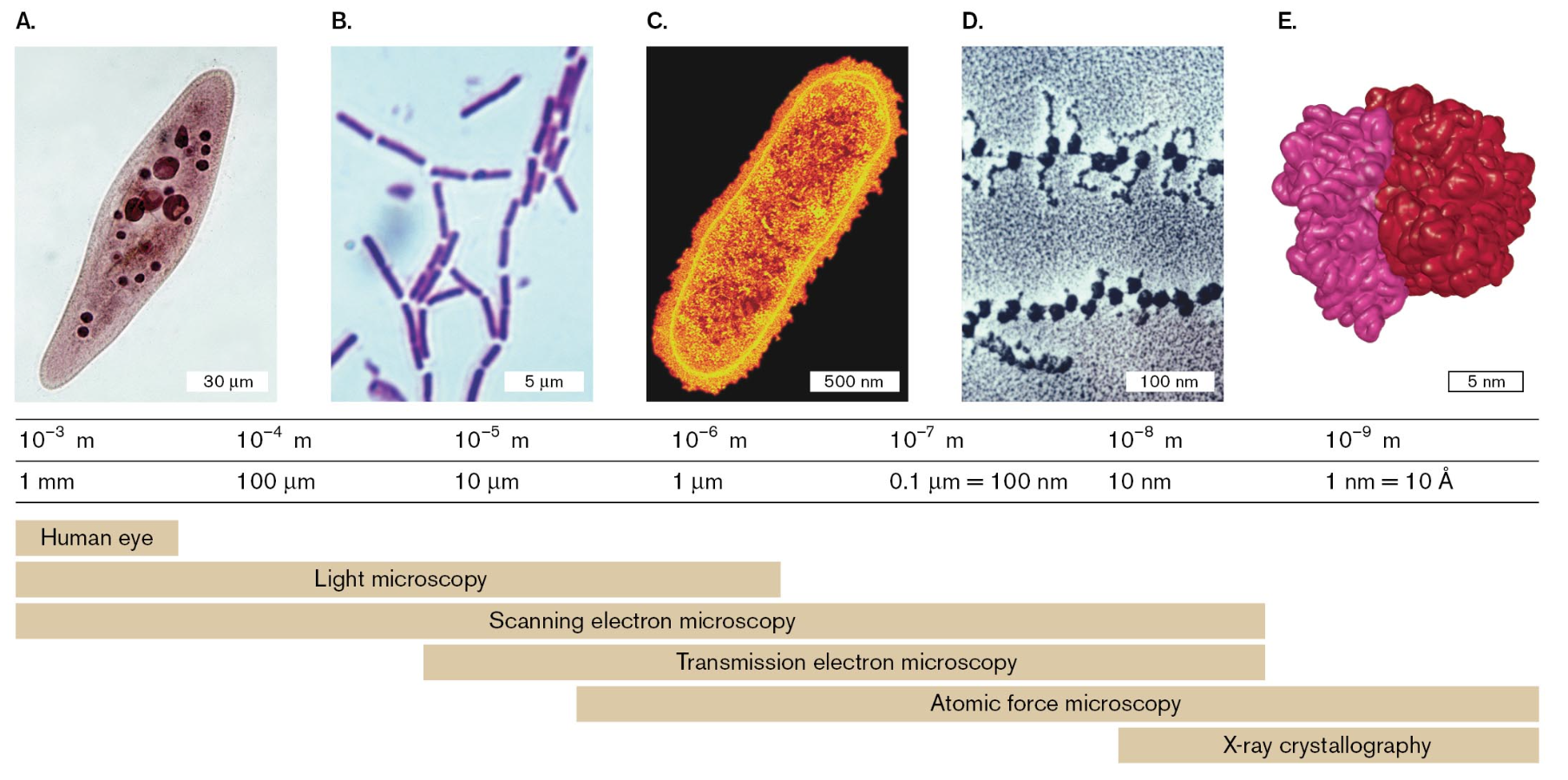

microscopy at different size scales

light microscopy (LM) - resolves images of individual bacteria by their absorption of light

bright-field microscopy - the specimen is commonly viewed as a dark object against a light-filled field

advanced techniques based on special properties of light include phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy

electron microscopy (EM) - uses beams of electrons to resolve details several orders of magnitude smaller than those seen under LM

scanning electron microscopy (SEM) - uses a beam of electrons that is scattered from a metal-coated surface of an object which can generate an appearance of 3D depth

transmission electron microscopy (TEM) - a type of EM microscope where the electron beam travels through the object and the electrons are absorbed by an electron-dense metal stain

chemical imaging microscopy - uses spectrometry to map the chemical contents of a specimen like distribution of nitrogen and carbon compounds

X-ray crystallography - detects the interference pattern of X-rays entering the crystal lattice of a molecule; from this pattern a computational model of the structure can be built of the individual molecule

optics and properties of light

regions of the electromagnetic spectrum are defined by wavelength

visible spectrum ranges from 400-750 nm

radiation of longer wavelengths includes infrared and radio waves

radiation of shorter wavelengths includes ultraviolet rays and x-rays

information carried by radiation can be used to detect objects

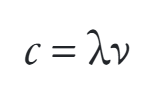

all electromagnetic radiation travels through a vacuum at 3 × 10^8 m/s (speed of light)

c is constant; the longer the wavelength, the lower the frequency of v (Hz)

wavelength limits the size of objects that can be resolved as separate from neighboring objects

requirements for resolution

contrast between the object and its surroundings

if an object and its surroundings absorb or reflect radiation equally, then the object will be undetectable

wavelength smaller than the object

the radiation must be equal to or smaller than the size of the object

if the wavelength of the radiation is larger than the object, then most of the wave’s energy will simply pass through the object

magnification

the smallest distance our retina can resolve is 150 um which means we are virtually unable to access all the information contained in the light than enters our eyes

we must adapt and spread the light rays far enough apart for our retina to perceive the resolved image

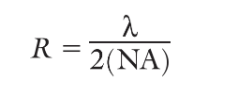

light interacts with an object

the physical behavior of light resembles a beam of particles, photons, and a waveform

each photon has an associated wavelength that determines how the photon will interact with a given object

the combined properties of particle and wave enable light to interact with an object in several different ways

absorption: the absorbing object gains the photon’s energy which is converted to a different form of energy; usually heat

when a microbial specimen absorbs light, it can be observed as a dark spot against a bright field (bright-field microscopy)

some molecules exhibit fluorescence which is when the absorbed light of a specific wavelength reemits energy as light with a longer wavelength

reflection: the wavefront redirects from the surface of an object at an angle equal to its incident angle

refraction: the light bends as it enters a substance / medium that slows its speed

a substance that exhibits this type of property is said to be refractive and has a higher refractive index than air

scattering: a portion of the wavefront is converted to a spherical wave originating from the object

if a large # of particles simultaneously scatter light, we observe a haze

magnification by a lens

refraction magnifies an image when light passes through a refractive material shaped so as to spread its rays

a parabolic curve is a type of shape that would spread light rays

when light rays enter a lens of refractive material with a parabolic surface, parallel rays each bend at an angle so that all the rays meet at a focal point

from this focal point, the light rays continue to spread out with an expanding wavefront

this expansion magnifies the image carried by the wave

focal distance is determined by the degree of curvature of the lens and by the refractive index of its material

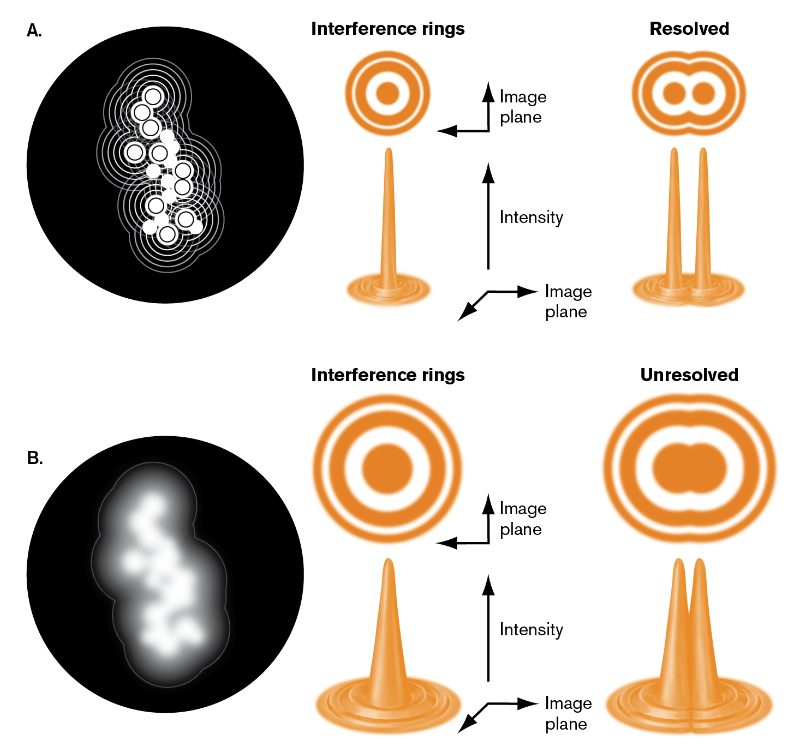

resolution of detail

empty magnification occurs when there is magnification without increasing detail

the resolution of detail in microscopy in limited by the wave nature of light

interference occurs because the width of the lens is infinite but light rays form wavefront of infinite extent so only part of the wavefront enters

the converging edges of the waves interfere with each other to form alternation regions of light and dark

when viewing a specimen with LM, each point source generates a central peak of intensity to which the width of this central peak will define the resolution between any two points of the object

this resolution determines the degree of detail that can be observed

factors that limit the resolution of an image

the wavelength of light limits the sharpness of the peak of intensity of a point of detail

the finite width of the wavefront captured by the lens leads to interference and widens the peak intensity

bright-field microscopy resolves only details that are greater than half the wavelength of light (about 200 nm)

super-resolution imaging can allow for the tracking of cellular molecules at a precision of 20-40 nm

magnification

wavelength & resolution

the greatest magnification that can improve our perception of what is usually 100-200 um is about 1,000x

any greater magnification expands the image size but the peaks expand without resolution between them (empty magnification)

light and contrast

balanced amount of light yields the highest contrast between the dark specimen and the light background

high contrast is needed to perceive the full resolution at a given magnification

lens quality

all lens possess aberrations that detract from perfect curvature

optical properties limit the perfection of a single lens but manufactures can construct microscopes with a series of lens to multiply each other’s magnification as a correction

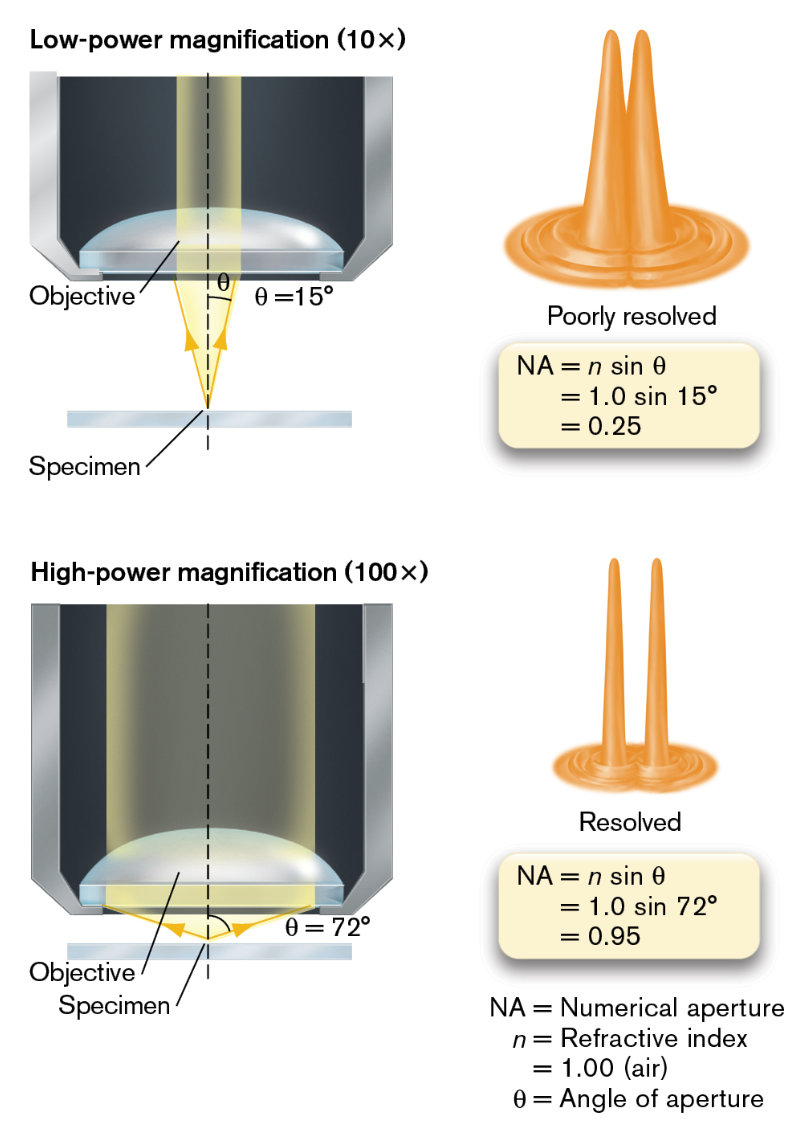

an object at the focal point of a lens sits at the tip of a cone of light formed by rays from the lens converging at the object

the angle of the light cone is determined by the curvature and refractive index of the lens

as theta increases, the horizontal width of the light cone increase giving way to a wider cone of light to pass through the specimen

the wider the cone of light rays, the less the interference between the wavefronts and the narrower the peak intensities in the image

a wider light cone enables us to resolve smaller details

the greater the angle of aperture of the lens will give better resolution

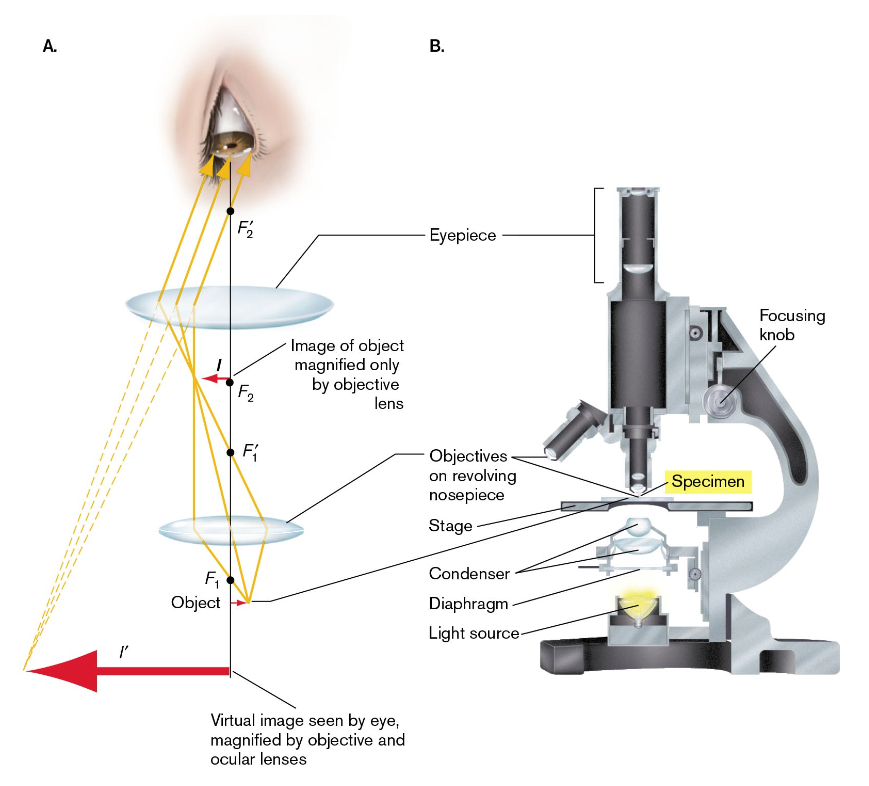

the compound microscope

a series of lower-power lens is used to multiply their magnification with minimal aberration (condenser & ocular lens)

lower-power lens require lower light levels because the excess light makes it impossible to observe the darkening effect of specimen absorbance

for higher-power lenses, they spread the light rays further and require an open diaphragm to collect sufficient light for contrast between the dark specimen and the bright field

condenser lenses increase light available for contrast but do not participate in magnification

in a parfocal system, when a specimen is viewed from one lens and the lens are rotated, it remains in focus

steps for observing a specimen under a compound microscope

position the specimen centrally in the optical column

optimize the amount of light to produce the optimal amount of contrast

focus the objective lens - typically start with a low-power objective which generates a greater depth of field

preparing a specimen for microscopy

wet mount; to observe microbes by placing a drop of water on a slide with a coverslip

advantages of wet mounting include: the organism being viewed is in it’s most natural state without artifacts resulting from chemical treatment

disadvantages of wet mounting includes: there is little contrast with the external medium and the specimen of interest (detection and resolution are minimal) & the sample can get easily dried out

the microbe observed must adhere to a specially coated slide within the temperature-controlled flow cell to avoid overheating

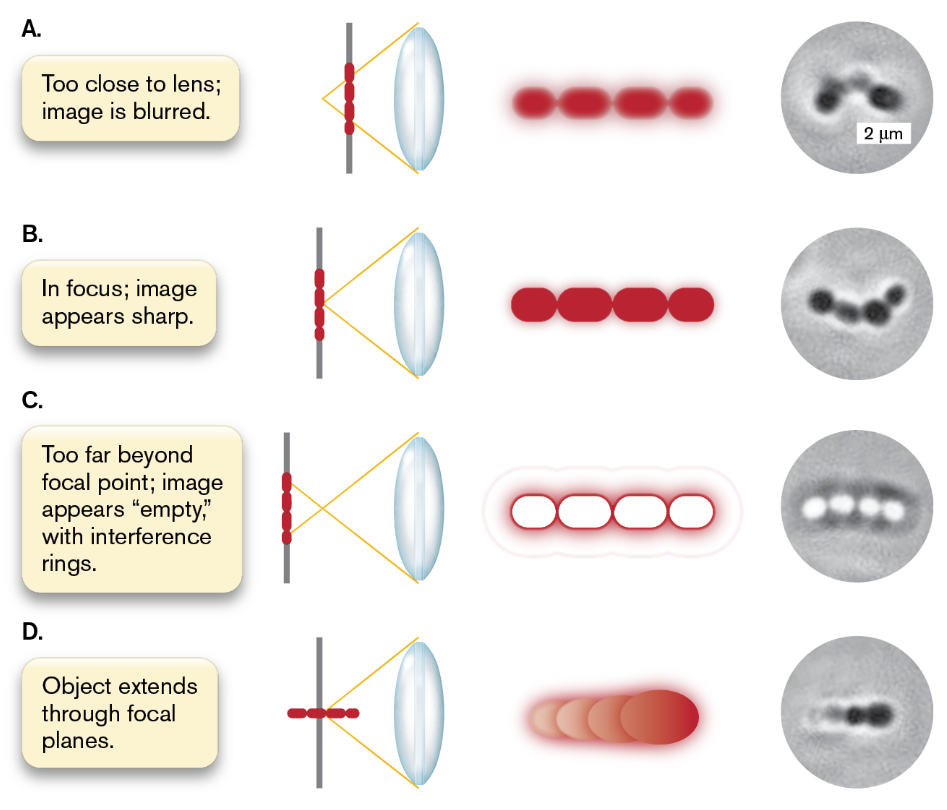

focusing the objects

the shape of the dark object is defined by points of light surrounding its edge when in focus

at higher power, these points of light are only partially resolved (limit of resolution reached)

partially resolution generates interference effects like extra rings of light

to observe motile bacteria, you must adjust the settings to have a higher magnification but a narrower depth of field

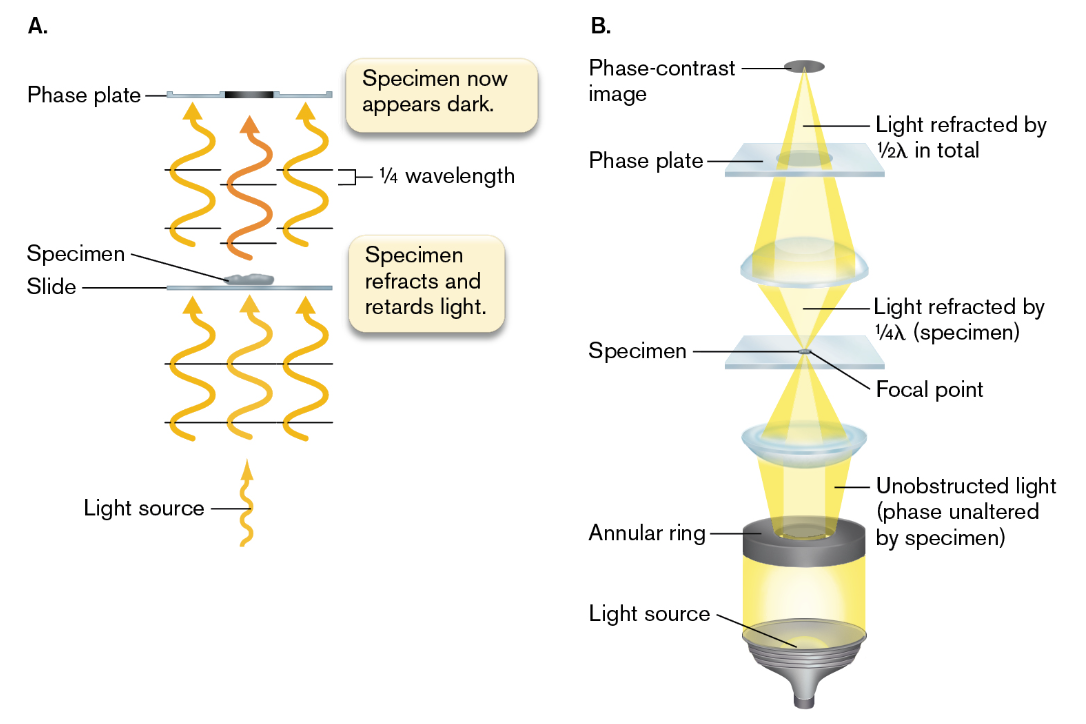

phase contrast microscopy

exploits differences in refractive index between the cytoplasm and the surrounding medium or between different organelles

depends on the principle of interference where two wavefronts interact with each other by addition or subtraction which results in alternating zones of constructive and destructive interference

addition - amplitudes in phase | subtraction - amplitudes out of phase

due to the fact that living cells have relatively high contrast because of their concentration of solutes, after light passes through the cell, about one-quarter of a wavelength behind the phase of light is transmitted directly through the medium

optical system is designed so that by the light refracted through the cell is slowed by a total of half a wavelength and when out of phase, it produces destructive interference (a region of darkness in the image of the specimen)

the light transmitted through the medium needs to be separated from the light interacting with the object

the transmitted light is separated by a ring-shaped slit (annular ring) which generates a hollow cone of light

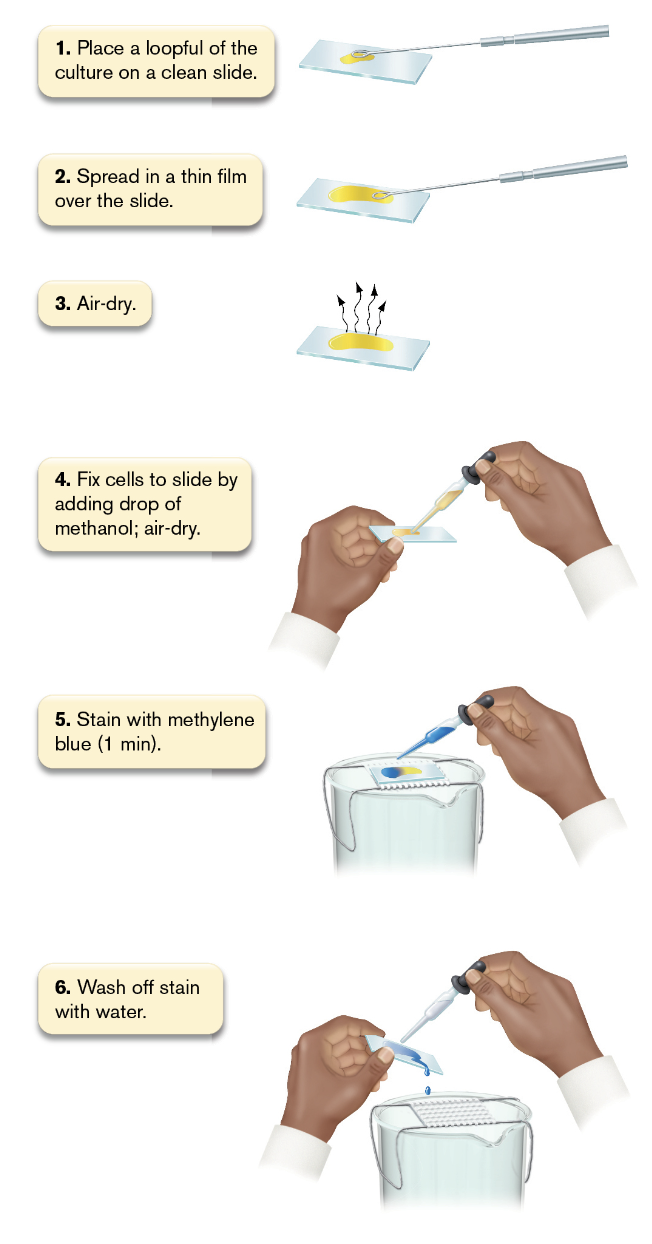

fixation & staining for bright-field microscopy

fixation - a process which cells are adhered to a slide in a fixed position

cells can be fixed by methanol or heat treatments in order to denature the cell’s proteins so the side chains are exposed and bind to the glass

staining - the use of molecule that absorbs the incident light, usually over a wavelength that results in a distinctive color

how stains work:

stain molecules contain conjugated double bonds or aromatic rings that absorb visible light & have positively charged groups that bind cell-surface components with negative charge

different stains will depend on the strength of their binding and the degree of binding to different parts of a cell

simple stains

adds a dark color to the specimen but not to the external medium or immediate surrounding tissue

most common simple stain used is methylene blue

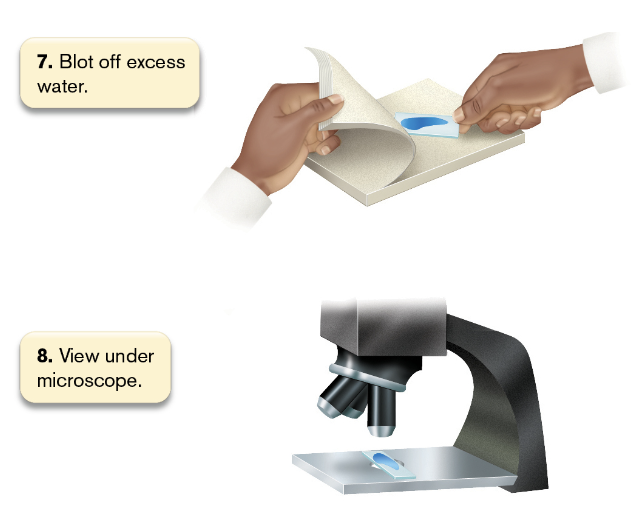

differential stains

this is a type of stain that differentiates among objects by staining only particular types of cells or specific subcellular structures

Gram stain - distinguishes cells that have a thick cell wall & retain a positively charged stain from cells that have a thin cell wall and outer membrane & fail to retain the stain

gram-negative cells usually stain red | gram-positive cells usually stain purple

Procedure for gram-staining

stain process: crystal violet dye, mordant (binding agent), decolorizer like ethanol, and counterstain (safranin)

during the stage of using a decolorizer, gram-positive cells appear dark purple and gram-negative cells appear colorless

the timing is important for each step because it can release the retained stain

in the decolorizer stage if over time then the gram-positive cells will release their crystal violet stain

in the counterstain stage if over time then both the gram-positive and gram-negative cells appear pink because of the safranin

acid-fast stain

a stain for mycobacteria that retain the dye fuchsin because of the presence of mycolic acids in the cell wall

giemsa stain for blood film

a mixture of methylene blue, eosin, and Azure B is used to stain blood cells & associated parasites

negative stain

a stain that colors the background and leaves the specimen unstained

a suspension of opaque particles such as India ink that is added to darken the surrounding medium and reveal transparent components of pathogens & microbes

antibody stains

stains linked to antibodies which can help identify precise strains of bacteria or molecular components of cells

the antibody may be conjugated to a reactive enzyme for detection

fluorescence microscopy

helpful to identify specific kinds of microbes and reveals specific cell parts function

for this type of microscopy, the specimen absorbs light of a defined wavelength and then emits light of lower energy

some microorganisms can fluoresce on their own due to the presence of chlorophyll

specific parts of the cell are labeled with a fluorophore

two different colors of fluorescence distinguish between the cyanobacterial cells performing photosynthesis and the heterocysts performing nitrogen fixation

excitation and emission

fluorescence occurs when a molecule absorbs light of a specific wavelength to raise an electron to a higher-energy orbital (excitation wavelength)

because this higher-energy electron state is unstable the electron will decay to an orbital of slightly lower energy, some E lost as heat

it will then fall back it’s original level by emitting a photon of less energy and longer wavelength (emission wavelength)

INSERT IMAGE HERE

the optical system for fluorescence microscopy uses filters to limit the source light to the wavelength range of excitation and the specimen’s emitted light to the wavelength range of emission

the wavelengths of excitation and emission are determined by the choice of fluorophore

fluorophores for labeling

a fluorophore’s properties is determined by the molecular structure of each fluorophore determines its peak wavelength of excitation and emission & its binding properties

the specificity of a fluorophore can be determined by:

chemical affinity - especially for biological molecules

labeled antibodies - antibodies that specifically bind to a cell component are covalently attached to a fluorophore which forms a “conjugated antibody” (immunofluorescence)

DNA hybridization - a short sequence of DNA attached to a fluorophore will hybridize to a specific sequence in the genome

gene fusion reporter - cells can engineered with a gene fusion which expresses a bacterial protein combined with either GFP or one of many GFP variants

super-resolution imaging

enables scientists to pinpoint the location of a DNA-binding protein with a precision tenfold greater than the resolution of an ordinary optical microscope

when tasked with tracking a single molecule, we must consider the shape of the magnified image of a point source of light

the uncertainty of the central peak position is about a tenth wide on the intensity profile and computation based on this profile can reveal the peak positions with high precision

confocal laser scanning microscopy

a microscopic laser light source scans across the specimen in such a way that the excitation light from at laser and the emitted light from the specimen are focused together to produce a high-resolution image

this type of imaging can be used for 3D imaging of pathogens embedded within host cell or tissue

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH can map specific taxa of microbes within an environment & can show the spatial location of microbial taxa

the FISH technique makes use of a fluorophore-labeled oligonucleotide probe that hybridizes to a microbe’s DNA or rRNA

doing so increases sensitivity because rRNA is present in approx 100-fold to 10,000-fold excess over DNA

chemical imaging microscopy

the use of mass spectrometry to visualize the distribution of chemicals within living cells

a high res method for chemical imaging is referred to as nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS)

has an ionizing probe which provides a source of energy that breaks up the large organic molecules of a sample

this instrument measures the fragment masses of the secondary ions that fly off the source which generates a mass spectrum