PSYC203 Social Judgements 2024-25 Part 1

Page 1: Introduction

PSYC203

Course Title: Social Beliefs and Judgements

Week: 18

Instructor: Dr. Jared Piazza

Institution: Lancaster University

Page 2: Overview of Today's Topic

Part 1 – Perceiving the Social World

The Use of Schemas

What are Schemas?

Cognitive structures that organize knowledge about a stimulus domain.

Focus Areas:

Role Schemas (stereotypes)

Structure and usage.

Impact on emotions, attention, and memory.

Stability and changeability of stereotypes.

Other Features:

Stereotypes, entitativity, essentialism, prejudice.

External validity of schema-related research.

Part 2 (Thursday):

Forming Judgments:

Heuristics, Attributions, & Explaining the Social World.

Page 3: Understanding Schemas

Definition of Schemas

Schemas: “...an abstract knowledge structure, stored in memory, that specifies the defining features of some stimulus domain (…) social schemas may be representations of types of people, social roles or events.” (Crocker et al., 1984)

Examples:

Objects (e.g., chairs, cats)

Concepts (e.g., love)

Events (e.g., lectures)

Groups (e.g., liberals, vegans)

Categorisation: Identifying instances of categories based on shared features.

Page 4: Features of Schemas

Once activated they facilitate top-down processing – incoming information is interpreted in terms of that schema

Contrasted with “data-driven” or bottom-up processing (Fiske, 1993

Schemas organize our world and thereby shape our expectations about the world

Schemas have “circumscribed accuracy” (Swann, 1984), i.e., they tend to be “typically functional” and “accurate enough” for navigating the world. But they often lead us to make prediction errors, e.g.:

We can miscategorise people (e.g., inferring political orientation from hair style or accent)

Members of a category do not share all the same features, therefore, we underestimate category heterogeneity (e.g., assume Jared is loud, friendly, likes guns and hamburgers because he’s American)

Page 5: Types of Schemas

Person Schemas: Traits related to types of individuals (e.g., neurotic).

Event Schemas (Scripts): Expected sequences in distinct situations (e.g., classroom vs. social events).

Self-Schemas: Cognitive representations about oneself based on past experiences.

Role Schemas (Stereotypes): Expectations about social roles based on societal context.

Page 6: Structure of Stereotypes

Prototypes and Exemplars

Prototypes: Prototypes are cognitive representations of a category (‘fuzzy set’) – based on collections of instances that share a family resemblance or defining properties (E.g. Spanish women are loud and emotional. They have dark hair and eyes.)

Exemplars: Specific instances representing a category (e.g., a Spanish actress).

Page 7: Associative Networks

Schemas are organized as associative networks

(Wyer & Carlston, 1994)

They involve representational content connected by learned associative links (e.g., men → aggressive; women → emotional)

Cognitive activation can spread through these networks through exposure to relevant stimuli (“priming”)

Priming of a schema shapes both

What we attend to in a social situation

What we remember of that social situation

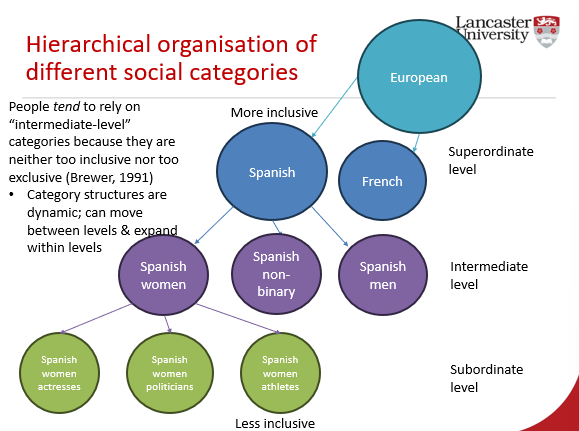

Page 8: Hierarchical Organization

Social Categories Hierarchy

Categories range from superordinate (broad) to subordinate (specific):

Example: Spanish Women → Specific group categories (e.g., actresses, politicians).

Individuals use intermediate-level categories for balance between inclusivity and exclusivity.

Page 9: Activation of Schemas

Conditions for Schema Use

In addition to intermediate-level categories, we tend to use schemas that are:

Cued by easily detected features

skin colour

Dress

Physical appearance

Features that are contextually distinctive

e.g., gender schemas (e.g., “men”) will be less accessible in an “all male” context than a single man in a group of women

Schemas that have a bearing on features that are important to oneself in that context

E.g., if ”race” or “nationality” are important categories, that are salient in memory and habitually used to process person information, then they are likely to be used

Schemas can be “primed” by relevant stimuli, often non-consciously

(Aarts & Dijksterhuis, 2003; Hassin et al., 2007)

If a schema has been used recently, it tends to be more accessible for reuse (Srull & Wyer, 1979, 1980; Todorov & Bargh, 2002)

Page 11: Schema Influence on Behaviour

Priming Effects

Primed schemas can influence judgments and behaviors, but enactment can vary.

Activation of a schema (“priming”), whether conscious or non-conscious, does not necessitate enactment of behavioural goals

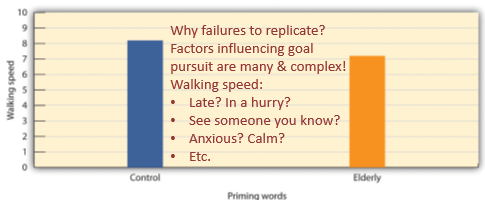

Page 12: Behavioural Priming Example

Study by Bargh et al.

Unscrambling Task: Participants primed with age-related words led to behaviours indicating aging (e.g., walking slower).

Other age-associated terms used to prime the schema for ‘elderly’, e.g., ‘old’, ‘wise’, ‘retired’, ‘grey’, ‘wrinkles’

Walking slower = schema-congruent behaviour (Bargh et al., 1996)

Replication issues

However: Doyen et al. (2012) failed to replicate the effect

There are replication issues in social priming studies, esp. w/ behavioural outcomes (see also Harris et al., 2013; Pashler et al., 2012, 2013)

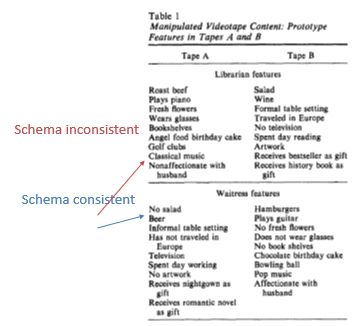

Page 14: Attention and Memory Influences

Study by Cohen (1981)

Two versions of the video, overall quite similar, but each had some “schema-congruent” and “schema-incongruent” features

Participants learn that the woman is either:

Participants were more likely to remember schema-consistent rather than schema-inconsistent information

E.g., when participants are told that the woman is a librarian they remember her drinking wine, eating salad and wearing glasses (regardless of whether it’s correct)

E.g., when they are told the women is a waitress they are more likely to remember her drinking beer, eating a hamburger and not wearing glasses (regardless of whether it’s correct)

Conclusion: selective processing and retrieval of the scene and details guided by schema (stereotype)

Meta-Analyses Findings

However, findings emerged from meta-analyses provide a more complex picture

Rojahn and Pettigrew (1992) and Stangor and McMillan (1992) found that schema-inconsistent information (e.g., a librarian without glasses!) is sometimes remembered better (because it is novel and distinctive)

Recall and recognition tests (corrected for guessing) suggests schema- inconsistent information is remembered better

Recognition tests (not corrected for guessing) suggests schema-consistent information is remembered better

Be wary of relying on a single method or individual studies! (CWA reminder)

Page 18: Evaluative Nature of Schemas

Affective Response

As a set of normative expectations, schemas are inherently evaluative (Fiske, 1982)

I.e., when you encounter someone (Jared), they are immediately compared against the relevant schemas (lecturer, American, man, White, etc.)

This evaluation often generates an affective response

E.g., the stereotype of “tattooed-man” may include associations of aggression and thereby elicit anxiety

E.g., the stereotype of a “senior lecturer at UK university” may include a stuffy, posh accent and thus Jared (lacking this trait) elicits surprise & confusion

Page 19: Acquisition and Development of Schemas

Learning Process

They are constructed and develop by direct and indirect experience w/ the social environment (including parents, peers, TV, media, etc.)

Initially, in early childhood, they comprise simple, independent and unintegrated units

e.g., boys wear blue; boys play with guns; boys don’t cry, etc.

With experience (i.e., more instances of a category encountered), schemas become more detailed, integrated and complex (Linville, 1982; Park 1986)

e.g., boys are good at maths, are competitive, play sports, don’t show vulnerability, like eating meat, drink excessively, etc.

They also begin to incorporate exceptions and contradictions

Huston (1983) found gender schemas become less rigid in middle to late childhood (e.g., some boys are not interested in sports, express their emotions, enjoy a good salad, etc.)

Page 20: Stability and Change of Schemas

Schema Rigidity and Adaptability

Schemas are highly stable and resistant to change; they persist in the face of contradictory evidence (Crocker, Fiske & Taylor, 1984)

Leading us to miscategorise people and underestimate category diversity

However, they can be changed! Rothbart (1981) and Weber and Crocker (1983) identified 3 models of schema change:

Book-keeping – constant updating of the schema over time; accumulating contradictory experience results in gradual change

e.g., encountering more and more boys practicing a vegetarian diet will ”quiet” the association between “boys” →”eat meat”

Conversion – encountering inconsistencies don’t result in change at first, but schemas can change suddenly once a critical mass of disconfirming evidence has accumulated

Subtyping – disconfirming instances are relegated to subtypes of the schema (hierarchically organised) – this tends to preserve the schema

E.g., “Introverted Spanish women”, or “Spanish women without dark hair” get subtyped (i.e., treated as a subordinate category), which results in the “Spanish women” prototype (i.e., central features: outgoing, dark hair) being preserved.

Page 22: Subtyping Example

Evidence of Subtyping - Hewstone, Hopkins and Routh (1992)

‘School police officer’ encountered as part of a police-school liaison scheme

Used a card-sorting task with school pupils to assess beliefs about 24 authority figures, including this target occupation

‘Foot patrol police officer’, ‘police officer in transit van’ , ‘woman police officer’ and ‘mounted police officer’ were grouped together as having similar characteristics

‘School police officer’ was categorised separately and as having characteristics more in common with ‘teachers’ and ‘social workers’

Arguably, this was evidence for subtyping, i.e., the schema ‘police officer’ was not updated to include a school-based police officer

Page 23: Conditions Where Schemas Are Unused

Situational Factors

Under certain conditions, individuals are less likely to use schemas and employ more careful “bottom-up” or data-driven processes

When there are costs of being wrong (Erber & Fiske, 1984; Neuberg & Fiske, 1987)

E.g., when accountable for one’s decision or need to justify one’s actions

When there are NO costs of being indecisive and can take ones time (Jamieson & Zanna, 1989)

E.g., when NOT under time pressure or distracted (Wilder & Shapiro, 1989)

Individual differences in awareness that “stereotyping” (schema use) is often inaccurate and may lead to prejudice

E.g., People more comfortable with uncertainty and cognitive complexity use schemas less (Crockett, 1965; Sorrentino & Roney, 1999)

Page 24: Conceptual Foundations of Entitativity and Essentialism

Understanding Essentialism

Entitativity

First introduced by Campbell (1958) refers to the extent to which a social category (e.g., ‘men’) is perceived to be a unified, coherent and meaningful entity

Connected to ‘Psychological Essentialism’ (Medin & Ortony, 1989)

a tendency to believe that social categories have essences, i.e., that they are an immutable ‘natural kind’, rather than being socially constructed (see also Yzerbyt & Rocher, 2002)

Haslam et al. (2000, 2002): Believing that a social category is entitative and essentialised might support prejudice

Page 25: Stereotypes and Their Features

Haslam, Rothschild and Ernst (2000)

40 social categories, e.g., age (young, old), gender (male, female), personality (extroverts, introverts) rated on nine elements related to essentialism and entitativity, e.g.:

–Discreteness – ‘Some categories have sharper boundaries than others’

–Uniformity – ‘Some categories contain members who are very similar to one another’

–Informativeness – ‘Some categories allow people to make many judgments about their members’

–Naturalness – ‘Some categories are more natural than others’

–Immutability – ‘Membership in some categories is relatively immutable; it is difficult for category members to become non-members’

–Stability – ‘Some categories are more stable over time than others’

–Inherence – ‘Some categories have an underlying reality; although their members have similarities and differences on the surface, underneath they are basically the same’

Findings

Essentialised categories:

i.e., were seen as discrete, natural, immutable, and stable categories with “necessary” features

Included: Gender (e.g., female, male), Ethnicity (e.g., Asian, Hispanic) and Race (e.g., Black, White) exemplified “natural kinds”

Highly entitative categories:

I.e., were seen as uniform, highly informative, and exclusive categories

Included: Politics (e.g., liberal, Republican), Religion (e.g., Catholic, Jew), Sexual orientation (e.g., heterosexual, homosexual)

Page 27:Stereotypes, essentialism & prejudice

Haslam, Rothschild and Ernst (2002)

Essentialism & entitativity in relation to sexism and racial prejudice

Essentialised categories:

‘Black people’ and ‘Women’ exemplified “natural kinds”

However, essentialism ratings were not related to measures of racism or sexism

Highly entitative categories:

‘Gay men’ were seen as an entitative group, i.e., as uniform, highly informative, and an exclusive category

Entitative ratings related to measures of anti-gay attitudes

Page 28: Gender Essentialism and Transgender Attitudes

Gender essentialism

Gender essentialism involves the view of gender as binary (discrete), natural, and immutable

Might gender essentialism relate to transphobic attitudes?

Research by Norton and Herek (2013)

Sample of 2,281 heterosexual men and women

Measured attitudes towards transgender people, using feeling thermometer, along with sexual-orientation groups (e.g., “bisexual men”), “men in general” and “women in general”

Also measured gender essentialism, political ideology, religiosity, etc.

E.g., “These days there is not enough respect for the natural divisions between the sexes.”

Page 29: Correlations Found

Negative attitudes (thermometer rating) towards transgender people were associated with:

•

•Endorsement of gender essentialism and higher political conservatism

•

•Conclusion: essentialising social categories (e.g., gender) can sometimes foster prejudice towards individuals that don’t conform to schema-based expectations

Page 30: Real-World Implications of Schemas

Correll et al. (2002) Study

Experimental manipulation of racial identity (Black vs. White target) in a ‘shoot/don’t shoot’ task

Time pressure: Participants given 850ms to decide “shoot” or “don’t shoot” (button press)

Four possible types of outcomes:

Hit – shooting an armed person

Miss – not shooting an armed person

False alarm – shooting an unarmed person

Correct rejection – not shooting an unarmed person

Racial bias and the ‘shoot/don’t shoot’ task. Findings:

Main effect of Object – i.e., more errors in the non-gun condition (false alarms – shooting an unarmed person) than in the gun condition (misses – not shooting an armed person)

Thus, already prone to shoot unarmed persons holding a non-gun object when under time pressure

Interaction between Ethnicity and Object – the tendency to make more false alarms (shoot an unarmed person) than misses (not shoot an armed target) was more pronounced for Black rather than White targets

Note: participants saw the person and the object at exactly the same time; thus, attending only to the object should result in no differences based on Ethnicity

Correll et al 2007 follow up study

Incorporated stereotype activation – participants read vignettes about Black or White violent criminals prior to the shoot/don’t shoot task

Exposure to stereotype-consistent information emphasising ‘aggressiveness’ of Black criminals (stereotype activation) increased racial bias – more lenient decision criterion for shooting Black targets

Exposure to ‘aggressiveness’ information about White criminals lowered decision criterion for shooting White targets

In this condition, participants were just as likely to shoot White targets as Black targets

Page 33: Limitations of Bias Studies

Ecological Validity Concerns

First person shooter task (FPST)

Static images (not moving)

Multiple trials in quick succession (more like a video game)

Keyboard button pushing (not pulling trigger)

No social context - no bystanders in images and lone participant

Isolated decision – not part of a dynamic interactional process

Lab-based – safe and consequence free

these studies have limited ecological validity and should be considered as preliminary

Other methods needed to establish convergent validity

Page 34: Recap of Part 1

Key Takeaways

Schemas provide for fast, efficient processing:

•Schemas are theory-driven structures – rely on prior knowledge to guide expectations

–May involve prototypes, exemplars, and associative networks; organised hierarchically

•Schemas influence attention/memory, are evaluative and affective, are learned/acquired over time, are BOTH stable and able to change

•Schemas are effort-saving devices – fast, automatic, and “typically functional”; but sometimes problematic, leading to prediction errors and reinforcing prejudices!

–They often involve essentialist notions of “natural kinds”; beliefs about categories being discrete, uniform, natural and immutable, which has been linked to prejudice (e.g., transphobia)

–Schema research has implications for real world issues but ecological limitations must be acknowledged

•