Banking Procedures Chapter 29 admin practice

A deposit is money (cash or checks) put into an account, increasing the account balance. A withdrawal occurs when money is removed from the account (by check, electronic fund transfer, withdrawal slip, or passbook), thus decreasing the account balance.

29-1: Banking

Online banking, or electronic banking, is the practice of performing transactions using the Internet. Mobile banking allows account holders to perform banking transactions by a mobile device such as a smartphone or tablet. In both of these methods of banking, all information and records related to the account are tracked and can be viewed online, offering convenience and real-time insights into account activity.

The automated teller machine (ATM) is a banking machine operated by inserting a debit, credit, or bank card and entering a personal identification number (PIN) code. Deposits, transfers, withdrawals, and other banking functions like balance inquiries can be performed at ATM locations, providing 24/7 access to basic banking services.

29-1a: Types of Bank Accounts and Services

The most common types of bank accounts are the checking account and the savings account.

Checking Account: A bank account in which money may be deposited and from which debit transactions can be made or checks written against. Banks issue checks, debit cards, and online access for these accounts, enabling frequent transactions for day-to-day expenses.

Savings Account: A bank account from which the depositor can earn interest on the stored funds. Beyond the basic "regular" savings account, other types include:

Custodial Account: Often set up for a minor, managed by an adult (custodian) until the minor reaches a certain age.

Money Market Account: A type of savings account that typically offers higher interest rates than a regular savings account but may require a higher minimum balance and might have limited check-writing privileges.

Overdraft Protection: An overdraft occurs when a charge for a purchase or a check written is more than the amount of funds available in the bank account. Banks typically charge substantial fees for overdrafts. Overdraft protection is a service that links your checking account to another account (like savings or a credit line) to automatically transfer funds to cover transactions if your checking account balance falls below zero, helping to avoid overdraft fees.

29-2: Currency

Currency is the name given to the cash we use in our society. It is made up of common paper bills in $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 denominations issued by the Federal Reserve. Cash also comes in the form of coins in the common denominations of 1 cent (penny), 5 cents (nickel), 10 cents (dime), and 25 cents (quarter).

Handling Cash in the Office:

When accepting cash in a professional office setting, specific precautions must be observed to ensure security and proper record-keeping:

Give the patient a prenumbered receipt for all cash payments.

Keep cash drawers separate from petty cash funds.

Only one person should be designated to handle cash in the cash drawer to maintain accountability.

All cash should be placed out of sight as soon as it is received and kept secured at all times in the medical office.

29-2a: Debit and Credit Cards

When accepting credit/debit cards, it is best practice to be vague on the receipt, for instance, by simply putting "medical services" to protect patient confidentiality. In addition to the possible loss of funds, identity theft of patients and potential HIPAA violations are significant concerns when handling sensitive payment information.

Pros and Cons of Accepting Credit and Debit Cards:

PROS OF ACCEPTING CREDIT CARDS

Easy to use and makes paying bills or making store purchases hassle-free for customers.

Businesses gain another payment option, attracting a wider range of customers.

CONS OF ACCEPTING CREDIT CARDS

Businesses incur small processing fees for each credit card transaction.

Credit card transactions add another layer of detail to your business’s bookkeeping practices.

PROS OF ACCEPTING DEBIT CARDS

Compared to credit cards, debit card payments generally have a faster approval time, which means faster access to revenue for the business.

Accepting debit cards gives your business access to consumers who may not have credit cards.

Because the debit process is similar to a cash transaction, the fees that a business pays on debit transactions are smaller than credit card or check fees.

CONS OF ACCEPTING DEBIT CARDS

Choosing to accept debit cards requires the minor step of adding a PIN pad to a credit card terminal.

As with credit card transactions, debit card use adds another layer of detail to your business’s bookkeeping practices.

29-3: Checks

A check is an order for a bank to pay money to the person or company named on the check from the account holder. While checks became common after World War II, they were rare before 1700.

Types of Checks and Related Terms:

Cashier’s Check: The purchaser pays the bank the full amount of the check, plus a service fee. The bank then writes a check on its own account, making it guaranteed funds acceptable to any party.

Certified Check: A personal check for which the bank guarantees payment. The bank certifies that the funds are available and will be held for the payee. This is a guaranteed check and is always acceptable when a personal check is not (though rare in an office setting).

Electronic Check (Electronic Bill Pay): A check paid directly from a checking account through the internet, facilitating faster and often automated payments.

Cryptocurrency: A digital or virtual currency that uses cryptography for security, making it difficult to counterfeit. The first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, was created in 2009 as a software-based online payment system (rarely accepted for payment in an office setting).

Limited Check: A check marked with "VOID" if it's written over a certain amount of money, usually indicating a spending limit or specific control mechanism.

Money Orders: A negotiable instrument used by individuals who may not have a checking account or to meet specific requirements for purchasing an item or service where cash or personal checks are not accepted. Ensure a postal money order does not have more than one endorsement, unless issued to multiple payees using "and," as a single, additional endorsement makes it invalid.

Stale Check: A check that is too old to deposit, typically after 90 days or six months (depending on bank policy or pre-printed instructions). A preprinted date requirement such as "void after 60 days" also makes a check invalid after that specific period.

Postdated Check: A check with a future date. It is not valid before the specified date.

Traveler's Check and Voucher Check: These are other types of checks that are rarely used or accepted for payment in most office settings today.

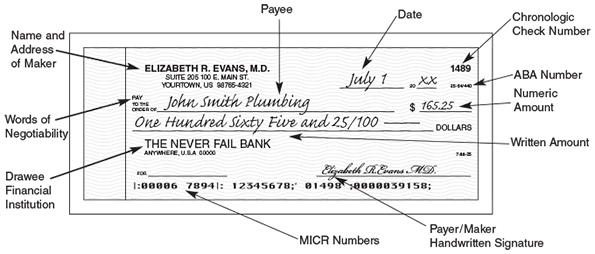

29-3a: Check Components

Seven components must be present on a check for it to be considered valid:

Date: This is the date the check is written. It’s crucial to watch for a postdated check (a future date), a stale date (usually six months or older), or a preprinted date requirement such as "void after 60 days." A check with these features is not valid before or after a specific period of time.

Words of Negotiability: On a check, the phrase "Pay to the order of" indicates that the check is negotiable, meaning it can be transferred from one party to another.

Payee: The check must clearly identify to whom the check is written (the person or entity receiving the funds).

Numeric Amount: This is the amount of the check written in numbers, typically placed in the dollar box.

Written Amount: This is the amount of the check written out in words. For example, a check for 25.89 is written as "Twenty-five and 89/100 dollars." A line should be filled in the remainder of the space to prevent fraudulent insertion of words to illegally increase the amount.

Drawee Financial Institution: This identifies the bank or financial institution where the check is payable.

Signature: The check must bear the signature of the person owning the account or other designated individuals authorized to issue funds. The payer is the person who signs the check, also known as the maker.

Additional Check Identifiers:

Check Routing Symbol or ABA Number: A code number found in the right upper corner of a printed check (sometimes above the check number on a business check or below on a personal check). It is typically in fractional form (44/119) on business checks or hyphenated (25-61) on personal checks. Originated by the American Bankers Association (ABA), its purpose is to identify the geographic area where the bank on which the check is written is located and to identify the specific bank within that area. This number is crucial for the check clearing process.

Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR) Numbers: These are numbers and symbols printed at the bottom of a check using magnetic ink, which aids in the efficient check clearing process. The MICR line contains the nine-digit routing number (also known as the ABA number) for the financial institution, as well as the specific checking/savings account number and the check number.

29-3b: Check Endorsement

An endorsement is the payee’s signature on the back of a check, which is necessary for the check to be cashed or deposited. All checks received in the office, whether in person or through the mail, should be protected by endorsement immediately upon receipt.

Restrictive Endorsement: This type of endorsement is used to ensure checks can only be deposited into a specific account. It is typically a stamp or written information that states, "PAY TO THE ORDER OF (name of bank where check is to be deposited)" followed by the name of the provider. If such a check is stolen, it could not be fraudulently used in any way.

Dealing with Incorrect Payee Name: If the name of the endorser or payee is spelled incorrectly on the face of the check, it should be endorsed exactly as it is misspelled on the check, followed by the correct signature directly below it.

29-3c: Accepting Checks from Patients

When accepting checks from patients, it is critical to examine them for validity to avoid returned checks and associated fees. Do not accept checks with the following issues:

The written amount does not match the numeric amount.

The check is not dated or has an incorrect date, especially an incorrect year.

The check is not signed by the payer.

The signature of the payer does not match the one on file (if possible to verify).

Modified or altered checks.

A check marked "paid in full" or "payment in full" on the memo line, unless it truly does pay the account in full, including charges incurred on the day the check is written. If there is still a balance, accepting and depositing such a check may prevent you from collecting the remaining amount. It is appropriate to ask the patient to change the memo to note the Date of Service (DOS) instead of a "paid in full" notation.

Additional Precautions:

Verify that the check has all seven components that make it valid and that no corrections or alterations have been made.

It is generally best practice NOT to accept a third-party check (a check made out to the patient by someone unknown to the office). Most banks no longer accept any form of third-party check.

Refuse checks written for more than the amount due, preventing patients from receiving cash back from the office.

When an NSF (Non-Sufficient Funds) check comes in, call the bank to verify funds before attempting to re-deposit.

When you receive a check, stamp it promptly with the deposit endorsement (restrictive endorsement) to protect against theft.

Patient financial obligations for services rendered often include copayments, coinsurance, charges for non-covered services, and unmet deductibles. These should be clearly communicated.

29-3d: Preparing Checks

When preparing checks for payment from an office account, ensure all fields are accurately completed to prevent errors and facilitate proper processing:

Date: The month can be written out or numerical (e.g., July 8, 20XX, or 07/08/20XX).

Payee: Clearly specify the person or entity to whom the check is addressed.

Numeric Amount: Write the exact dollar amount in numbers clearly in the dollar box.

Written Amount: Write the dollar amount in words, followed by the cents as a fraction (e.g., "Twenty-five and 89/100"). Fill in any remaining space with a line to prevent insertions that could alter the amount.

Payer Signature: The authorized person owning the account or a designated individual must sign the check. The payer is also known as the maker.

29-3e: Completing the Check Register

The check stub or register must be accurately completed as a comprehensive record of transactions. It shows the check number, the person to whom the check is paid, the amount of the check, the date, and the current balance. It is kept by the person writing the check as a continuous record of the transaction.

Steps to Complete the Stub or Register Properly:

Use black or blue ink for clarity and permanence.

Enter the check number if it is not preprinted.

Enter the date of the transaction.

Identify the payee (the person or entity receiving the payment).

Bring forward the balance from the previous stub or entry.

List any deposits made since the last entry.

Enter the amount of the check being written.

Calculate and enter the new balance.

An authorized office member completing banking tasks is considered an agent, meaning they are authorized to act on behalf of another person (their employer, the provider). Similarly, bank officials act as agents for the bank.

Handling Mistakes: If a mistake is made while writing a check, it is necessary to write "VOID" across both the check and its corresponding stub, and then write a new one. This voided check should be filed with your canceled checks as it must be available for auditing purposes.

29-4: Bank Deposits

A deposit slip is an itemized list of cash and checks placed into a checking account. It is important to keep a copy of all deposit slips to verify deposits and maintain accurate financial records.

Preparing for a Deposit:

To prepare for a deposit, you will complete a deposit slip. All checks should be endorsed by restrictive endorsement only before being prepared for deposit.

Sorting Currency:

Put all bills of the same denomination together.

Face all bills the same direction, portrait side up.

Stack bills in order from highest to lowest denomination (e.g., $50s, $20s, $10s, $5s, with $1s at the top of the stack).

Sorting Checks:

Ensure that every check has been properly endorsed.

Arrange checks facing up from the largest amount to the least amount.

If a money order (MO) is received, identify it as "MO" and note the payee’s name.

If there are more checks than can be listed on the front of the deposit slip, use the back, total the amount, and bring that total forward to the correct line on the front.

Finally, total the amount of all checks (and cash) and enter it on the slip.

After depositing, a deposit record is provided by the bank to the customer as proof of the transaction.

It is a good security practice to vary the deposit day and time if possible so that office routines do not become predictable to potential observers.

29-4a: Other Types of Deposits

An important form of deposit is an electronic fund transfer (EFT), which credits or debits accounts by computer without the direct involvement of physical checks or deposit slips. Direct deposit is very common in the United States, especially for payroll. Payments from insurance companies are almost exclusively made via EFT, streamlining financial transactions.

29-4b: Stop Payment on Checks

Stop payment is a method by which the maker of a check can instruct their bank to refuse to honor a specific check, preventing it from being cashed or deposited. Banks typically charge a sizable fee for this service.

29-5: Bank Statements

A bank statement is a comprehensive record of an account sent to the account holder, usually on a monthly basis. It details the beginning balance, all deposits made, all checks drawn, all bank service charges, any interest earned, and the closing balance for the statement period. In addition, banks often offer the ability to request a mini bank statement through an ATM, which usually contains a summary of the last 10 transactions made on an account.

29-5a: Reconciling a Bank Statement

When a bank statement is received, it is essential to verify that the amounts on the bank statement are consistent or compatible with the amounts recorded in the office’s check register. This crucial process of confirming and adjusting discrepancies between the bank's records and your own is referred to as reconciling the bank statement, bank statement reconciliation, or bank reconciliation.

Pros and Cons of Accepting Credit and Debit Cards

PROS OF ACCEPTING CREDIT CARDS | CONS OF ACCEPTING CREDIT CARDS |

|---|---|

Easy to use and makes paying bills or making store purchases hassle free for customers. | Businesses see small processing fees for each credit card transaction. |

A business that accepts credit cards gives customers another payment option. | Credit card transactions add another layer of detail to your business’s bookkeeping practices. |

PROS OF ACCEPTING DEBIT CARDS | CONS OF ACCEPTING DEBIT CARDS |

Compared to credit cards, debit card payments generally have a faster approval time, which means faster access to revenue. | Choosing to accept debit cards requires the minor step of adding a pin pad to a credit card terminal. |

Accepting debit cards gives your business access to consumers who do not have credit cards. | |

Because the debit process is similar to a cash transaction, the fees that a business pays on debit transactions are smaller than credit card or check fees. | As with credit card transactions, debit card use adds another layer of detail to your business’s bookkeeping practices. |

Importance of Inventory Control and Purchasing

Running out of supplies creates crises; may halt or compromise patient treatment.

Effective inventory control:

Prevents stock‐outs.

Reduces waste and expired products.

Controls overhead and increases profitability.

A well-managed purchasing system aligns with inventory control to optimize costs.

Policy responsibility:

Physician establishes written policies.

A designated business-office employee executes the policies (ordering & record keeping).

All other staff must cooperate by reporting when a supply reaches its reorder point.

Computerized vs. manual systems:

Computerized programs exist, mostly cost-effective for high-volume retail or warehouse settings.

For most medical offices, a structured manual (card-file) system is still the least expensive and most flexible solution.

Establishing an Inventory Control System

Key Terms & Formulas

Reorder Point (ROP):

Minimum on-hand quantity that serves as an adequate reserve.

When on-hand inventory falls to this level, a reorder is triggered.

Generic formula: \text{Reorder Point} = (\text{Rate of Use} \times \text{Lead Time}) + \text{Margin of Safety}

Order Quantity (OQ):

Optimal amount purchased per order.

Balances unit price discounts, storage limits, shelf life, and expected consumption.

Determining the Reorder Point

Three essential factors:

Rate of Use – average consumption per time unit.

Lead Time – elapsed time between placing and receiving an order.

Margin of Safety – buffer to absorb delivery delays or sudden usage spikes.

Example: Dr. Taylor’s Welcome Brochures

Rate of use calculation:

10 new patients/week + ~10 extra brochures for friends/visitors.

\text{Rate of Use} = 20\;\text{brochures/week} \approx 80\;\text{per month}

Lead time: custom printing requires 2 weeks → 40\;\text{brochures} consumed during lead time.

Margin of safety: practice is growing; choose 60 brochures total as ROP (covers lead time plus safety).

Interpretation: When supply hits 60, immediately reorder.

Determining the Order Quantity

Influencing factors (apply each systematically):

Rate of Use – avoids too-frequent small orders or large stagnant stock.

Storage Space – bulky items (e.g., paper towels) may limit quantity; brochures are compact.

Shelf Life – perishable drugs vs. non-perishable brochures.

Probability of Continued Use – updated products could make large stock obsolete.

Quantity Price Breaks – supplier discounts for larger lots.

Brochure Example (price-break analysis)

Supplier prices:

100 \rightarrow \$25 (2-month supply)

200 \rightarrow \$40 (4-month supply)

500 \rightarrow \$95 (10-month supply)

Dr. Taylor recently updated brochures, expects current design longevity ≈ 10 months.

Chooses 500 units for \$95 to leverage best unit cost while still within usable timeframe.

Final brochure parameters:

\text{Order Quantity} = 500

\text{Reorder Point} = 60

Card-File Inventory System (Manual Method)

Objective: Simple, low-cost, highly visible tracking.

Core Components

Inventory Control Card (4″×6″):

Fields recorded:

Product name (and cross-reference names/brands).

Order quantity.

Reorder point.

Order source: supplier name, address, phone, rep, catalog #.

File Box & Index:

Cards filed alphabetically behind A–Z dividers.

If card volume is large, create two boxes: Clinical Materials vs. Office Supplies.

Metal File Signals (colored tabs):

Placed upper-left → “Need to Order”.

Moved upper-right → “On Order”.

Removed → “Received & stocked”.

Red Flag Reorder Tags:

Paper tags marked with item name & reorder point.

Physically embedded at the ROP location (e.g., 100th chart from bottom, attached to remaining Band-Aid stack).

When tag appears, it’s handed to the ordering clerk.

Step-by-Step Usage Protocol

Create & file a card for each significant supply; set red flag markers on current stock.

When ROP is reached, staff pulls the red flag and gives it to purchaser.

Purchaser places metal file signal in “order” position, attaching red flag to card if desired.

Place order promptly, noting date/quantity; slide signal to “on-order” position.

Upon receipt, log date/quantity/price on card; remove both signals.

Stock new items behind older stock (“first-in, first-out”); re-insert red flag at new ROP position.

Guidelines for Ordering Supplies

Be Prepared:

Audit inventory; consult physician for new/changed preferences before meeting reps or phoning orders.

Be Specific:

Provide catalog #, detailed description (brand, style, size), desired quantity, and verify current pricing.

Purchase Orders (large practices):

Pre-numbered form authorizing purchase; supplier may ask for PO # during ordering.

Handling Back Orders:

Supplier notice indicates item unavailable + expected ship date.

Decide: wait or cancel & reorder elsewhere; communicate cancellation if needed.

Be Informed:

Track specials, seasonal deals, conference pricing; but avoid “bargains” on items you don’t need.

Storing Supplies

Organizing the Storage Area

Conditions: cool, dry, clean, well-lit.

Fire safety: keep an inspected fire extinguisher; eliminate trash/clutter.

Ergonomics: heavy/bulky high-turn items on lower shelves; small groups in labeled bins.

Follow manufacturer storage directives:

Refrigeration (certain antibiotics, vaccines).

Light/radiation shielding (x-ray film).

Locked cabinets (controlled substances).

Moisture control for paper goods.

Label all shelves/bins for rapid identification and restocking.

Stocking Fresh Supplies (Receiving Routine)

Unpack shipment; verify contents against packing slip (no prices) or invoice (includes prices).

On inventory card, record:

Date received.

Quantity.

Latest unit/lot price.

Remove metal signals.

Restock using FIFO:

Place new items behind older ones.

Reinsert red flag at ROP location.

Worked Example: Patient Towels (Figure Data)

Consumption: 20\;\text{per day} \Rightarrow 100\;\text{per week}.

Shelf life: unlimited.

Storage: bulky; must stay dry.

Lead time: 2 weeks.

Variability: usage fluctuates; monitor for increases; watch for supplier specials.

Supplier price schedule:

1\;\text{carton} (500ea) = \$23

4\;\text{cartons} = \$75

Reorder point: \tfrac12 carton (250 towels).

Order quantity: 4 cartons (2,000 towels) to exploit bulk discount.

Practical, Ethical & Real-World Implications

Patient Safety: Continuity of care relies on uninterrupted availability of clinical materials (e.g., sterile gauze, medications).

Cost Containment: Efficient purchasing curbs unnecessary expenditures and allows resources to be allocated to technology or staffing.

Environmental Stewardship: Avoid over-ordering perishables that become medical waste.

Regulatory Compliance: Controlled substances require locked storage and accurate logs; expired drugs must be disposed per federal/state law.

Staff Accountability: Clear systems make it easy to trace responsibility for shortages or overstock.

Connections to Foundational Principles

Lean Management: Inventory control mirrors lean’s focus on eliminating waste (over-production, waiting, excess stock).

Supply Chain Risk Management: Margin of safety & lead-time buffers parallel broader concepts of resilience against disruption.

Basic Statistics: Rate of use often averaged over sampled weeks; can extend to moving averages or seasonal adjustments.

Summary Equations & Quick Reference

Core Reorder Formula: \text{ROP} = (\text{Average Daily Use} \times \text{Lead Time in Days}) + \text{Safety Stock}

Average Daily Use (ADU): \text{ADU} = \dfrac{\text{Total Units Used in Sample Period}}{\text{# Days in Sample Period}}

Economic considerations: compare \$\text{Total Cost} = \text{Unit Price} \times \text{Quantity} across price breaks; factor carrying costs if applicable.