PY 131 Chapter 2: Inertia and Newton's First Law

Motion

Physicists are interested in motion – how things change their position in space as time evolves.

There are many types of motion (some of which are related)

- Linear motion – moving in a straight line

- Projectile motion – linear motion in two spatial dimensions

- Circular / Rotational motion

- Rolling motion – a combination of linear and circular motion

- Vibrational / Harmonic motion

Linear Motion

Galileo Galilei was the world's first scientist.

He invented the Scientific Method and made many contributions to our knowledge of nature. From experiment Galileo discovered that moving objects do not require a force to keep them moving (in the absence of friction).

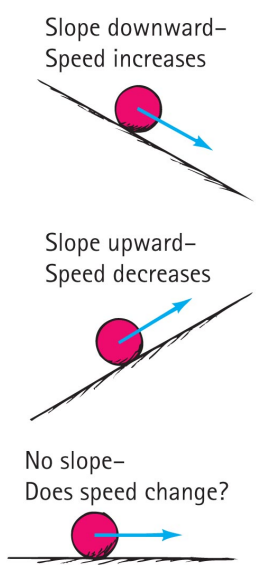

Balls rolling on downward-sloping planes pick up speed (accelerate) due to gravity.

Balls rolling on upward-sloping planes lose speed (decelerate) due to gravity.

So a ball on a horizontal plane neither accelerates nor decelerates - its speed remains unchanged indefinitely.

A ball on a horizontal plane eventually comes to rest due to friction/air resistance.

Newton’s First Law of Motion

- Galileo’s experimental discovery that objects resist changing their motion is now known as Newton’s First Law.

- Newton's First Law of Motion (Law of Inertia) states:

- An object at rest stays at rest unless acted on by an net external force. An object in motion continues to travel with constant speed in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force.

Force

The reason objects change how they are moving – if they are moving at all – is because a net force is applied.

- Just because something is not moving doesn’t mean there are no forces, only that there is no net force. Lots of different individual forces can act on something. Some well-known and less well-known forces:

- gravity (weight)

- tension

- friction

- normal force

- electrostatic attraction/repulsion, magnetism

The net force is the ‘sum’ of all the individual forces.

Force is an example of a vector: it has magnitude and direction.

Vector

- Many physical Quantities can be expressed as a single number.

- These quantities are known as scalars.

- Force (and some other Physical Quantities) cannot be expressed this way.

- Vectors have both size (magnitude) and direction.

- Vectors have units.

- Vectors can be represented by arrows.

- The length of the arrow is the size of the vector, the arrow points in the direction of the vector.

Adding vectors

Adding scalars is easy.

- The mass of object A is 4 kg and the mass of object B is 3 kg.

- The mass of the object you make when you glue A and B together is 4 kg + 3kg = 7 kg.

Adding vectors is different from adding scalars.

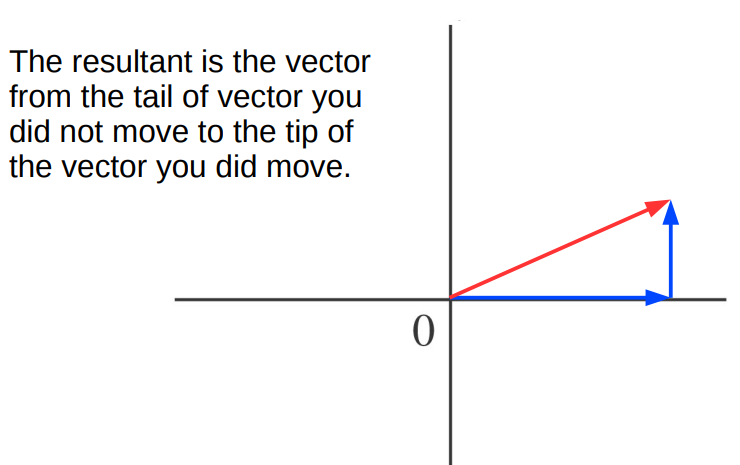

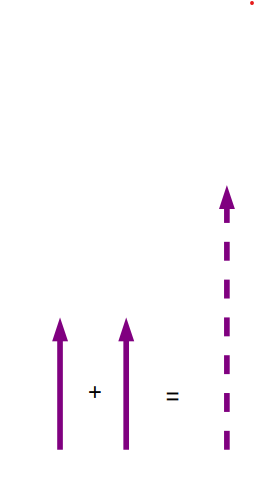

The sum of two (or more) vectors is called the resultant.

The resultant depends not only on the size of the vectors but also on their direction.

Vector Components

The sum of two (or more) vectors is also a vector.

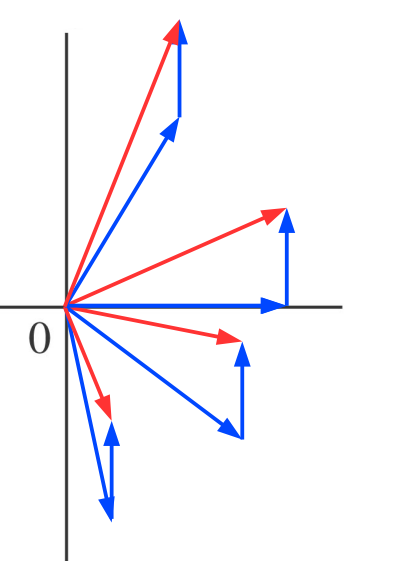

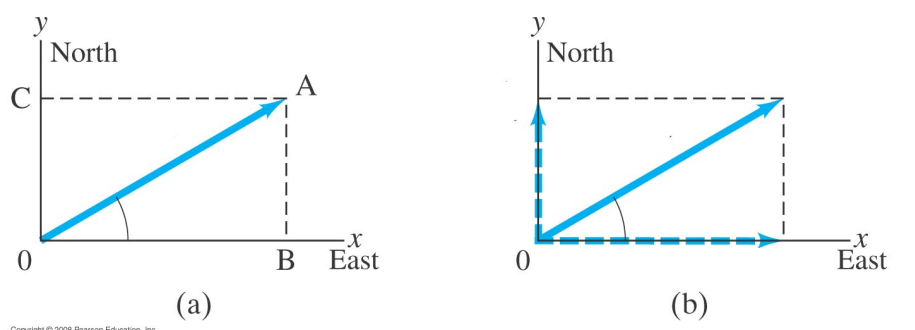

Given any vector, resolving a vector into its components means finding a set of vectors that sum to this vector.

- In essence, resolving a vector is the opposite of vector addition.

In general, the components of a vector are not unique.

The most common approach is to construct a set of axes and align each component of the vector with each axis.

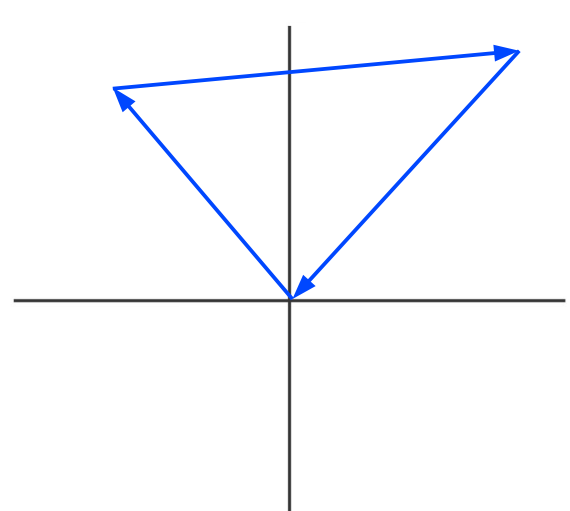

You can add 3 vectors of three different sizes to get zero.

Net Force

- The net force is what you get when you add all the force vectors acting on an object together.

- In math, the summation is often indicated by the Greek letter Σ so the net force can be written as

- ΣF

- Newton’s First Law is that when ΣF = 0, the object’s motion does not change.

- We say that the object is in mechanical equilibrium.

Weight (Normal/Gravitational Force)

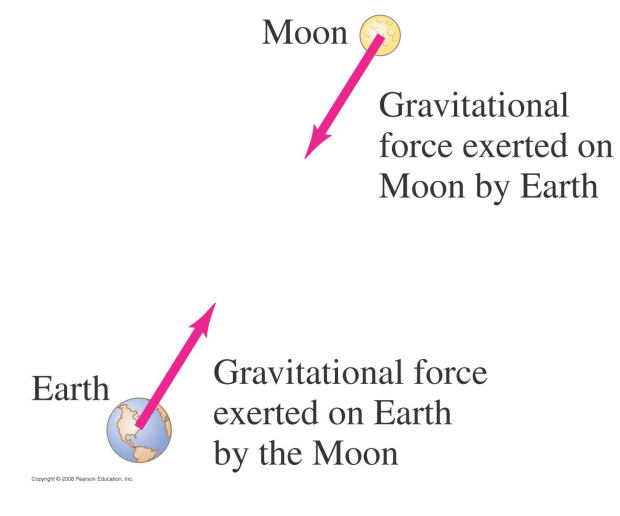

- Weight is the force due to gravity.

- Its origin is the mutual attraction of two objects with mass.

- It points along the line joining the Center of Mass of each object.

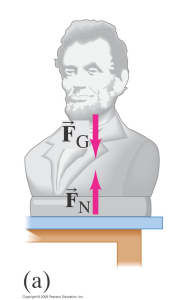

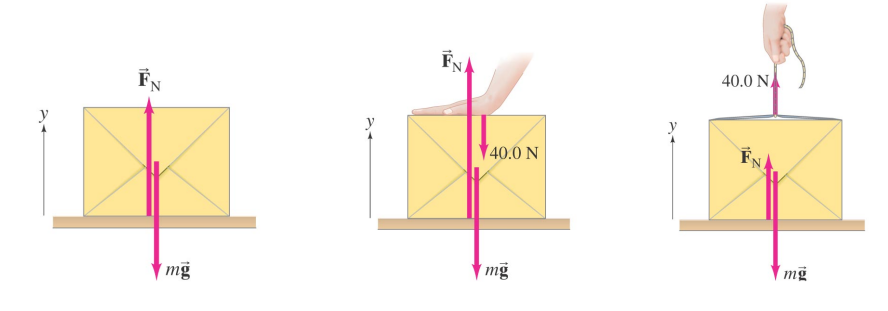

Normal (Support Force)

Consider an object at rest on a table. Since the object remains at rest, the net force must be zero. The force of gravity must be balanced by a second force. The force must be applied by the table.

When two objects are in contact there is a force between them.

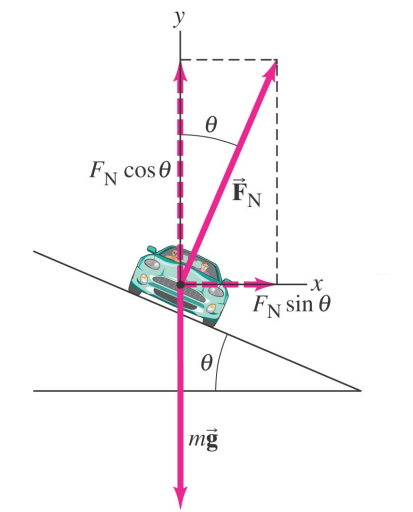

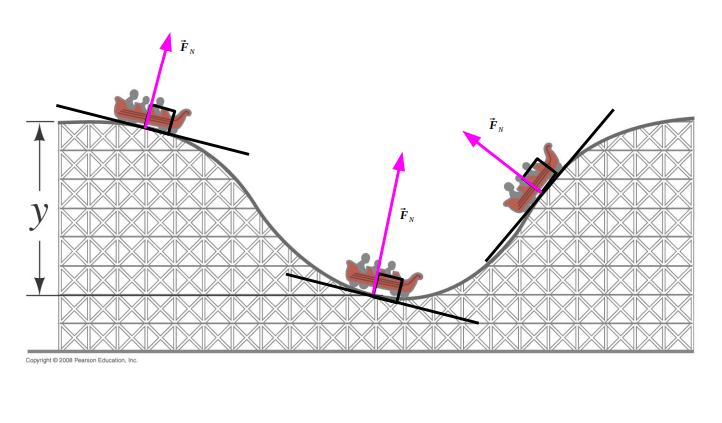

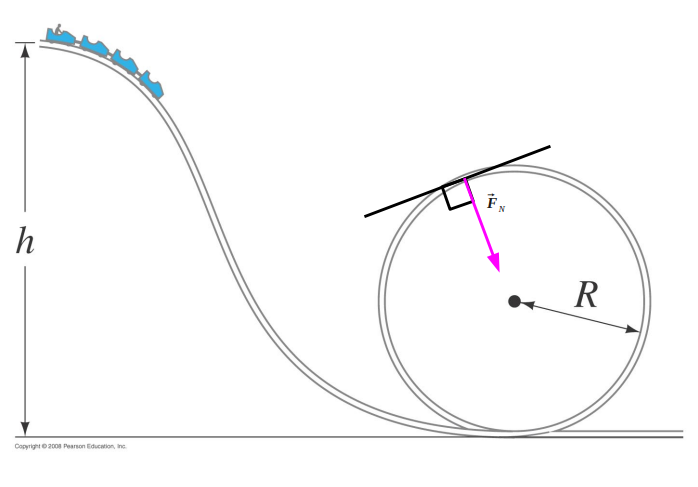

The normal force is so called because it points in the direction of the normal – the perpendicular – to a surface.

The normal force is not always equal to the weight nor vertical.

The normal force – not your weight - is what is measured by a scale.

- What do you see if you stand on two scales?

- If the scale measured your weight then each should show the same thing – your true weight.

- But what each shows is less than your true weight so the scale can’t be measuring your weight.

- The sum of the two readings will equal your weight. What the scales are showing are the two normal forces acting on you, one from each scale.

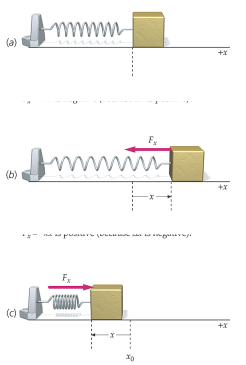

Spring Force

If a spring is compressed or stretched it exerts a spring force. The force opposes the stretch or compression. The greater the stretch or compression, the greater the spring force.

Tension

Strings/ropes/wires apply a pulling force.

- strings/ropes/wires cannot apply pushing forces.

The force from a string/rope/wire is often called tension. Tension is an example of a transmitted force.

- This means you apply a force to one part of the ‘force medium’ e.g. a rope, and the force is transmitted to another part of the medium (and eventually anything connected to the medium).

It is usually assumed the string/rope/wire does not stretch and is massless. In this case the transmitted force is the same as the applied force

- If neither is true then the transmitted force is less than the applied force.

- If you pluck two identical strings/ropes/wires which have different tensions, the one with the higher tension will vibrate at a higher frequency

EXAMPLE 1

A bowling ball is in equilibrium when it

- A. is at rest.

- B. moves steadily in a straight-line path.

- C. Both of the above.

- D. None of the above.

==c. Both of the above==

Equilibrium means no change in motion, so there are two options: If at rest, it continues at rest. If in motion, it continues at a steady rate in a straight line.

EXAMPLE 2

You push a crate at a steady speed in a straight line. If the friction force is 75 N, how much force must you apply?

- A. More than 75 N.

- B. Less than 75 N.

- C. Equal to 75 N.

- D. Not enough information.

==C. Equal to 75 N==

The crate is in dynamic equilibrium, so, ΣF=0. Your applied force balances the force of friction

EXAMPLE 3

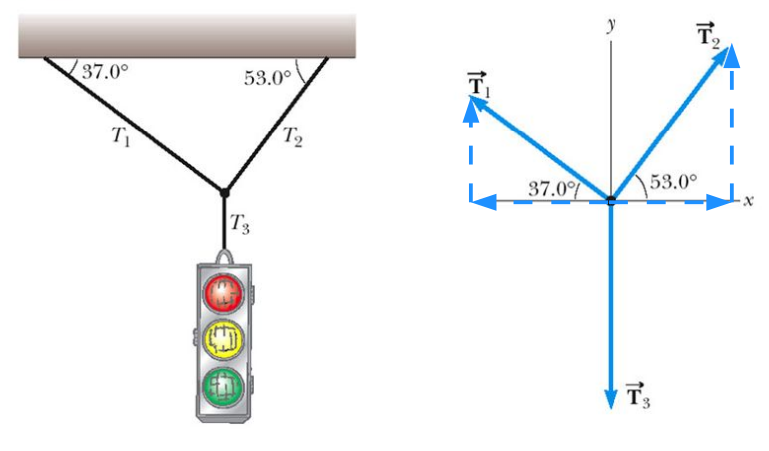

Two identical stationary masses are hung as shown. For which scenario are the tensions in the ropes the largest?

==The one on the right.==

EXAMPLE 4

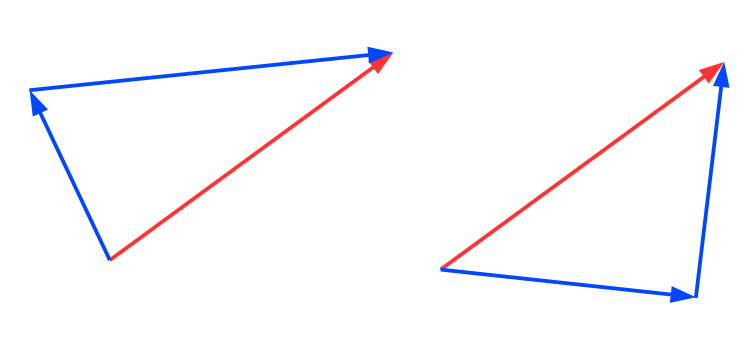

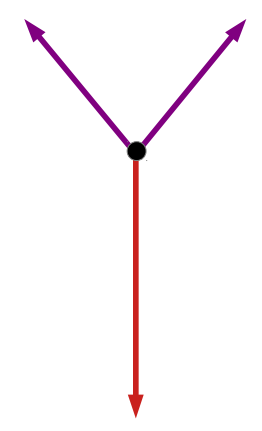

There are three forces acting on each mass: two tensions, one weight. These forces are in equilibrium: the resultant of the tensions must balance the weight. Consider the mass on the left hand side. The forces act on the mass like this:

The net tension is twice the length of each separately, therefore the weight of the block must be so that the net force on the mass is zero.

Now consider the mass on the right-hand side. Again it is in equilibrium and we now know the weight. The three forces act upon the block like this.

The resultant of the tensions still has to equal the weight.

Because the tensions are not aligned, the length of the arrows (the size of the tensions) must be greater than before (the ‘heights’ are the same).

The horizontal components of the tensions T1 and T2 cancel each other, and the vertical components of T1 and T2 cancel with T3.