Lecture 8_7Feb2025_before class

Lecture 08: Microbial Growth, part 2

BIOL 2221: Foundations of Microbiology

Date: February 7, 2025

Page 2: Today's Topics

Environmental Limits on Microbial Growth

Temperature

Salt

pH

Living with Oxygen: Aerobe vs. Anaerobe

Microbial Communities and Cell Differentiation

Syphilis

Due next 2

Page 4: Learning Objectives

Identify different microbial classes based on preferred environmental niches (pH, temperature, salt).

Describe biological properties allowing microbes to grow in extreme environments.

Page 5: Introduction to Microbial Growth Rates

Microbes display a wide range of growth rates.

Fastest growth: Hot-springs bacteria can double every 10 minutes.

Slowest growth: Deep-sea microbes may take 100 years to double.

Growth rates influenced by nutrition and environmental parameters (temperature, pH).

Page 6 & 10: Environmental Limits on Microbial Growth

Bacteria: The most metabolically diverse organisms.

Key growth considerations:

Temperature and pressure

Osmotic balance

pH level

Oxygen (O₂) levels

Normal conditions: sea-level pressure, temperatures 20–40ºC, neutral pH, 0.9% salt, ample nutrients.

Extreme niches: Conditions outside these limits, inhabited by extremophiles.

Page 7: Temperature Preferences

Organisms have optimal temperature ranges for cell membranes and proteins.

Page 8 & 9: Living at Extreme Temperatures

Thermophiles & extreme hyperthermophiles: Survive in thermal springs.

Psychrophiles: Adapted to icy environments.

Adaptation mechanisms:

Thermophiles: Saturated fatty acids in membranes for stability.

Psychrophiles: Unsaturated fatty acids provide membrane fluidity.

Page 11: Osmotic Pressure Adaptations

Halophiles (extreme) : Thrive in high salt concentrations (10–20% NaCl).

Maintain low internal Na+ levels; excrete excess with ion pumps.

High salt/sugar media can cause cell dehydration, halting growth.

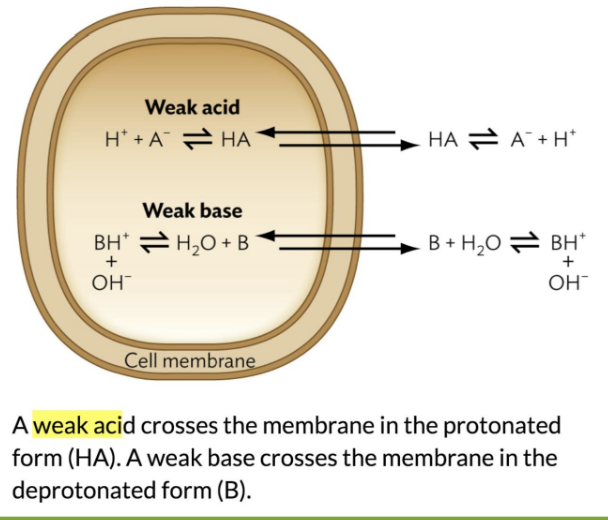

Page 12 & 13: pH and Microbial Growth

pH levels crucial for microbial survival.

Bacteria regulate internal pH, with weak acids disrupting homeostasis (used in food preservation).

All enzymatic activity depends on pH; protein structure affected by H+ concentration.

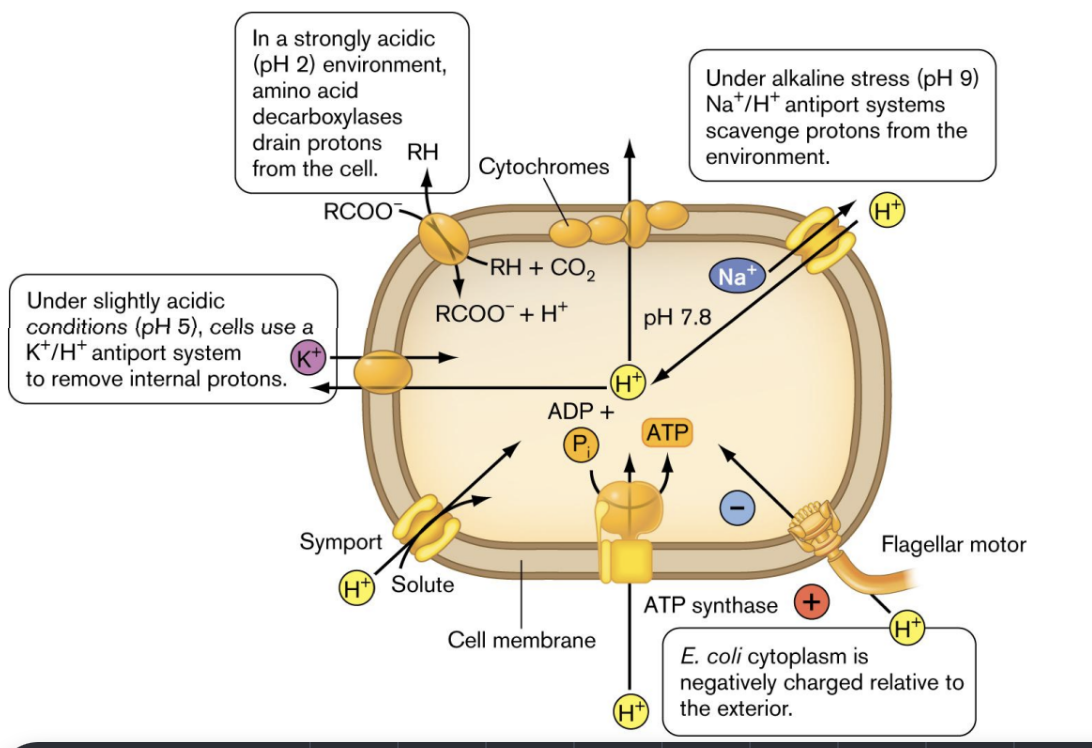

Page 14: Mechanisms for pH Homeostasis

Microbial strategies to maintain pH:

Acidic (pH 2): Amino acid decarboxylases pump out protons.

Alkaline (pH 9): Na+/H antiport systems scavenge protons.

Slightly acidic (pH 5): K+/H antiport systems expel internal protons.

Page 16: Learning Objectives on Oxygen

Differentiate between anaerobes and aerobes.

Describe groups based on oxygen requirements.

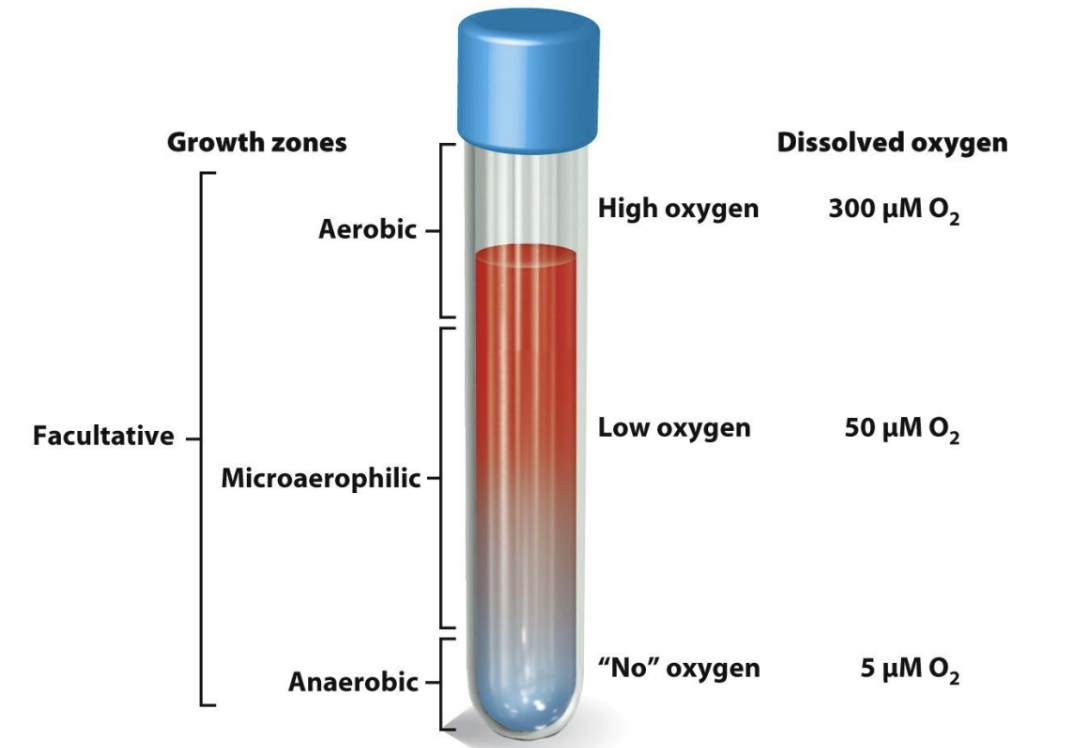

Page 17: Oxygen-Related Growth Zones

Growth varies with oxygen levels:

Aerobic: High O₂

Facultative: Can use O₂ or alternate pathways

Microaerophilic: Prefer low O₂

Anaerobic: No O₂ usage.

Page 19: Oxygen for Energy Metabolism

Many microbes utilize oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor (aerobic respiration).

Processes involved:

Removal of high energy electrons from glucose.

Electron transport chains extract energy and pump H+ ions.

Water is formed as byproduct from oxygen.

Page 21: Comparison of Fermentation and Aerobic Respiration

Aerobic respiration yields higher energy (ATP) compared to fermentation.

Page 26: Types of Aerobes and Anaerobes

Strict Aerobes: Require oxygen and can detoxify ROS.

Strict Anaerobes: Do not use oxygen; typically sensitive to ROS.

Microaerophiles: Prefer low oxygen but can neutralize some ROS.

Facultative Anaerobes: Function in both oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor environments, can neutralize ROS.

Aerotolerant Anaerobes: Do not mind oxygen but do not use it for metabolism.

Page 29: Learning Objectives on Biofilms and Endospores

Understand biofilm structure and significance in infections.

Understand properties of endospores.

Page 30: Case History - Death by Biofilm

Cystic fibrosis leads to microbial infections like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, linked to severe respiratory diseases.

Issues with treatments in biofilm-associated infections.

Page 31: Understanding Biofilms

Most bacterial growth occurs in biofilms, multi-species surface-attached communities (e.g., dental plaque).

Page 33: Properties of Biofilms

Communication via quorum sensing.

Increased resistance to antibiotics.

Major contributors to implant-associated infections.

Page 35: Endospores

Certain Gram-positive bacteria produce endospores for survival under adverse conditions.

Examples: Bacillus anthracis, Clostridium species.

Page 37: Properties of Endospores

High resistance to environmental stressors due to protective layers.

Dormancy lasts for decades, requires no nutrition.

Page 38: Summary of Microbial Survival Strategies

Microbes can thrive in extreme conditions and have developed unique adaptations.

Page 40-49: Syphilis Overview

Syphilis: Caused by Treponema pallidum, manifests in stages: primary (chancre), secondary (rash), tertiary (organ involvement).

Congenital syphilis involves serious complications in newborns, including neurosyphilis.

Prevention focuses on safe sex and regular screening, while treatment often involves penicillin.

Knowt

Knowt