CHEM 131 Midterm 1 Notes

Lecture 1

/

Dalton’s Theory of the Atom (1803):

Elements are made up of tiny, indestructible particles called atoms.

Atoms of one element cannot change into other atoms of another element — they can only change the way they are bound with other atoms

All atoms of a given element have the same mass and have properties that distinguish them from atoms of other elements

Atoms combine in whole ratios to form compounds

Properties of Protons:

Mass: 1.67262 × 10^-27 kg

Mass: 1.00727 amu

Relative Charge: 1+

Properties of Electrons:

Mass: 0.00091 × 10^-27 kg

Mass: 0.00055 amu

Relative Charge (1-)

Properties of Neutrons:

Mass: 1.67493 × 10^-27 kg

Mass: 1.00866 amu

Relative Charge: 0

Isotopes:

Isotopes are elements that have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons (ex: Carbon12)

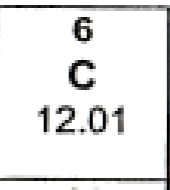

Parts of Periodic Table:

6 = atomic number (Z)

C = element symbol

12.01 = atomic weight

Electrons and Ions

Ions are charged atoms

The number of electrons in a neutral atom is equal to the number of protons in its nucleus

In chemical changes, however, atoms can lose or gain electrons and become charged particles called ions

Positively charged ions are called cations

Metal elements (Na+)

Negatively charged ions are called anions

Nonmetal elements (F-)

Lecture 2

Dalton’s Model of the Atom:

Elements are made up of tiny, indestructible particles called atoms.

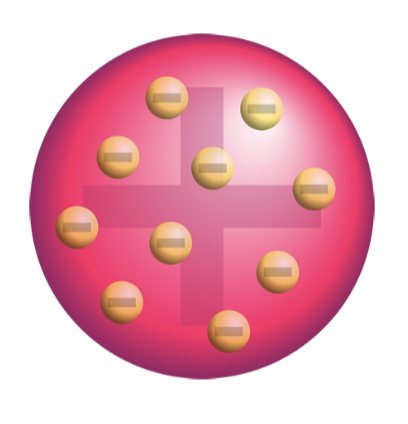

The Plum Pudding Model of the Atom:

Atoms contain negatively charged particles called electrons

Electrons exist in a positively charged space

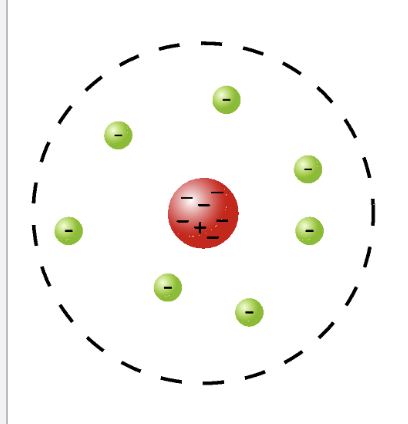

The Nuclear Model of the Atom:

Most of the atom’s mass and all of its positive charge are contained in a small core called the nucleus

Most of the volume of the atom is empty space, throughout which tiny negatively charged electrons are dispersed

There are as many negatively charged electrons outside the nucleus as there are positively charged particles (protons) inside the nucleus —> keeps the atom electrically neutral

Also neutral particles within the nucleus (neutrons)

The Bohr Model of the Atom

Nucleus remains the same (p+, n0)

The electrons (e-) travel in orbits that are at a fixed distance from the nucleus

These orbits correspond to discrete/quantized energy levels

Electrons release energy when they transition from an orbit with higher energy down to an orbit with lower energy (we see that energy as light)

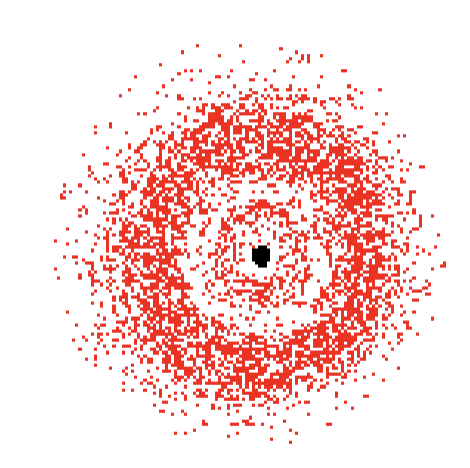

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

Nucleus remains the same (p+,n0)

The electrons do not travel in orbits

Electrons exist in probability domains that predicts their position ~95% of the time

Electrons are considered to be neither a particle nor a wave (have both characteristics)

Wave nature: interference pattern

Particle nature: position, which slit is it passing through

Schrodinger’s Equation:

allows us to calculate the probability of finding an electron with a particular amount of energy at a particular location in the atom

The resulting value describes a probability domain in which can electron can be found ~95% of the time

Lecture 3

Think of quantum numbers as a hotel:

“n” - floors

“l” - rooms

“ml” - numbers of rooms of a type

“n” - principal quantum number (energy level)

n = integer = 1,2,3,4,5,6,7…

example: n=2, means electron is in the second energy level

higher n value, higher energy level

increased size of probability domain (location of electron) with a larger n value

Energy Levels in a Hydrogen Atom

Lyman Series: produced when electrons in a hydrogen atom transition from higher energy levels to the lowest energy level (n=1); emits photons of specific wavelengths

Balmer Series: produced when electrons in a hydrogen atom transition from higher energy levels to the n=2; emits photons of specific wavelengths

Passion Series: produced when electrons in a hydrogen atom transition from higher energy levels to the n=3; emits photons of specific wavelengths

Higher energy level to lower energy level - releases energy

Lower energy level to higher energy level - absorbs energy

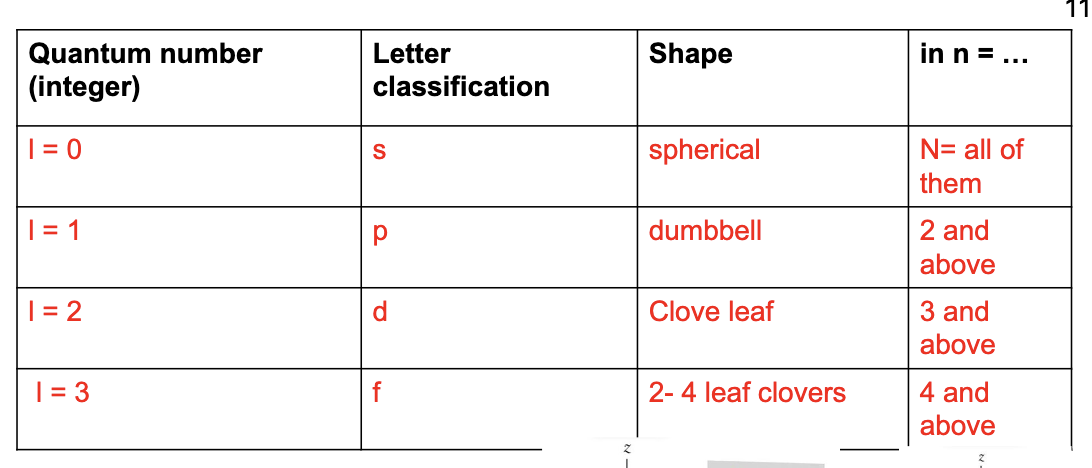

“l” - angular momentum quantum number (orbital type)

l=0 - s orbital (spherical)

l=1 - p orbital (dumbbell)

l=2 - d orbital (clover leaf)

l=3 - f orbital (2-4 leaf clovers)

ml - magnetic quantum number (which orbital/orientation/subshell)

Lecture 4

l=0 (s), ml=0

l=1 (p), ml=-1,0,1

l=2 (d), ml=-2,-1,0,1,2

l=3 (f), ml=-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3

s-orbital:

n=1 and up

l=0

ml=0

p-orbital:

n=2 and up

l= 1

ml=-1,0,1,

d-orbital:

n=3 and up

l=2

ml=-2,-1,0,1,2

f-orbital:

n=4 and up

l=3

ml=-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3

Pauli Exclusion Principle: no two electrons can have the same four quantum numbers (no more than two electrons can occupy the same orbital and the two electrons in the same orbital must have opposite spins)

An electron can be found in the lowest energy orbital available (ground state) 95% of the time.

The orbital lowest in energy is whichever orbital can get electrons the closest to the nucleus.

Coulomb’s Law

Particles of like charge repel (so that energy lowers when they separate)

Particles of unlike charges attract (so that energy lowers when they get closer together)

The larger the charges, the larger the energetic effects are

Z-effective: the total amount of attraction that an electron feels for the nucleus’s protons is called the effective nuclear charge (Zeff) of the electron

Shielding: inner electrons of an atom block the positive charge of the nucleus from reaching the outer charge —> inner electrons “shield” the outer electrons from the full nuclear charge (causes lower Zeff)

Penetration: the shape of orbitals allow electrons the possibility to get closer to the nucleus, which lowers its energy overall (if an outer electron had the possibility to get closer to the nucleus it would take it)

Lecture 5

Aufbau Principle: electrons enter (e.g. fill) atomic orbitals from lowest energy to highest

Hund’s Rule: Electrons will always enter empty orbitals before they pair up

Ex: find the valence and core electrons of the following electron configurations (try looking at n and l once you got to d)

Sodium: 1s2,2,s2,2p6,3s1

Valence: 1

Core: 10

Bromine: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s2,3d10,4p5

Valence: 7

Core: 28

Calcium: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s2

Valence: 2

Core: 18

Phosphorus: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p3

Valence: 5

Core: 10

Titanium: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s2,3d2

Valence: 4

Core: 18

When electrons become ions, they gain or lose electrons to achieve a full valence shell (2 or 8 electrons)

Electrons are gained from the valence shell to fill it

Electrons are lost from the valence shell to empty it and unveil the full shell underneath

Typically, metals will lose electrons and non-metals will gain electrons.

Lecture 6

Writing Elements as Ions:

Sodium: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s1

Na+ (lose one electron to get to a full outer shell)

Bromine: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s2,3d10,4p5

Br- (gain one electron to get to a full outer shell)

Phosphorus: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p3

P³-

Titanium: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s2,3d2

Ti4+ (an exception; it has multiple charges, with the preferred being 4+)

The Periodic Law: elements with similar properties recur in a regular patter (fall into columns)

The quantum-mechanical model explains this because the number of valence electrons and the types of orbitals they occupy are also periodic

Alkaline Earth Metals: Column 2A

Alkali Metals: Column 1A (except for hydrogen)

Halogen: Column 17

Noble Gases: Column 18

Transition Metals: Column 3-12

Other Nonmetals: Hydrogen + elements above staircase (B—> O —> Te —> B)

Other Metals: Below Staircase (Al —> Po —> Lv —> Nh—→ Al)

Noble Gases:

Full valence shells

particularly unreative and stable

Halogens:

One elctron short of full valence shell

Tend to gain one electron to form 1- ion (ex: F-)

Alkali Metals:

one electron beyond full valence shell

tend to lose one electron and form 1+ ion (ex: Na+)

Alkaline Earth Metals:

two electrons beyond full valence shell

tend to lose two electrons and form 2+ ion (ex: Ca2+)

s and p block, row number = n

d block, n= row number -1

f block, n= row number -2

Electron Configuration Exceptions:

Mo - [Kr] 5s1, 4d5

Cr - [Ar] 4s1, 3d5

Cu - [Ar] 4s1, 3d10

Ag - [Kr] 5s1, 4d10

Au - [Xe] 6s1,4f14,5d10

Electron configurations arise due to some elements having more stability with half-filled (like d5) and fully filled (like d10) orbitals. They reduce electron repulsion and create a more balanced, lower-energy arrangement of electrons.

Characteristics of atoms (and ions) which can be explained based on their position on the periodic table and either their Zeff (effective nuclear charge) or their n (principal quantum number)

Effective Nuclear Charge and Periodic Trends

Z is the nuclear charge, and S is the number of electrons in lower energy levels

Electrons in the same energy level contribute to screening, but since their contribution is so small, they are not part of the calculation.

Zeffective = Z (atomic number) - S (number of core/shielding electrons)

Examples:

Potassium: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6,4s1

Zeffective = 19 - 18 = +1

Chlorine: 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p5

Zeffective = 17 - 10 = +7

Lecture 7

Z-effective: effective nuclear charge, essentially how much of the nucleus’s positive charge an electron feels after considering the shielding effects of other electrons in an atom

Shorthand for Z-effective:

Only for neutral atoms, not ions

Atomic radius

distance between nucleus and valence electrons

as we move down the periodic table, we are adding another energy level, and therefore valence electrons are getting farther from the nucleus

ex: Na has smaller atomic radii than nucleus

atomic radii also increases as we go to the left of the periodic table

higher the Zeff, the more pull towards the nucleus, and the smaller the radii is going to be (higher Zeff on the right side of the periodic table)

Ionic Radii: Cations

Example: K+= 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6

Zeff= 19-10 = +9

Cations are smaller than their neutral counterparts

Ionic Radii: Anions

Example: Cl- = 1s2,2s2,2p6,3s2,3p6

Zeff= 17 - 10 = +7

Anions are larger than their neutral counterparts

Isoelectronic species: Ions or atoms that have the same number of electrons or a similar electronic structure

Ex: Neon (10 electrons) and Na+ (10 electrons)

Atoms with different atomic numbers (z) but same electron configuration

Can only compare Zeff among isoelectronic species

The species with the largest positive charge is the smallest (the highest Zeffective is going to have the smallest radii)

relationship between z-effective, radii, and ions flashcard

Ionization energy (IE)

the amount of energy required to remove an electron from an atom in its gaseous state

Energy is required → E+, formation of cation

Na(g) → Na+(g) + e-

IE1 = +496 KJ

Na+(g) → Na2+(g) + e-

IE2 = 4560 KJ

Ionization energy are successive

Ie1 (first electron), Ie2 (second electron), Ie3 (third electron)…

Ionization energy increases as we go to the right of the periodic table and up the periodic table

Electrons on the right hold on tighter to stay closer to the nucleus

Ionization energy increases with each successive removal of the outermost electron

Ionization energy and atomic radius are opposite in their trends.

Electron affinity (EA)

The energy change associated with the gaining of an electron by an atom in its gaseous state

measure of how easily an atom will accept an additional electron

electron affinity is usually (not always) negative because an atom or ion releases energy when it gains an electron (exothermic)

Noble gasses EA are always +

electron affinity gets more negative (excluding noble gasses) as you go from left to right

Lecture 7a

Why do atoms react to form molecules?

to achieve full valence shells

H, He → 1s2

Two ways that atoms will achieve a full valence shell:

Ionic: one atom will give an electron(s); another atom with take it/them

Covalent: two atoms will share electrons

Ionic Bonding

not quite a bond, but an attraction

ion-ion (electrostatic) interaction

between a metal and a nonmetal

electrons will be lost and gained

metal → cation (+)

nonmetal → anion (-)

Example: NaCl → sodium loses an election (Na+) and Cl gains an electron (Cl-)

oppositely charged ions are held together by ionic bonds, forming a crystalline lattice.

Covalent Bonds:

occur between two or more nonmetals. the atoms share electrons between them, composing a molecule.

covalently bonded compounds are also called molecular compounds

example - bond between nitrogen and oxygen (both nonmetals)

Naming Ionic Compounds

Ionic compounds can be categorized into two types, depending on the metal in the compound

with naming ionic compounds, no need to look at subscript

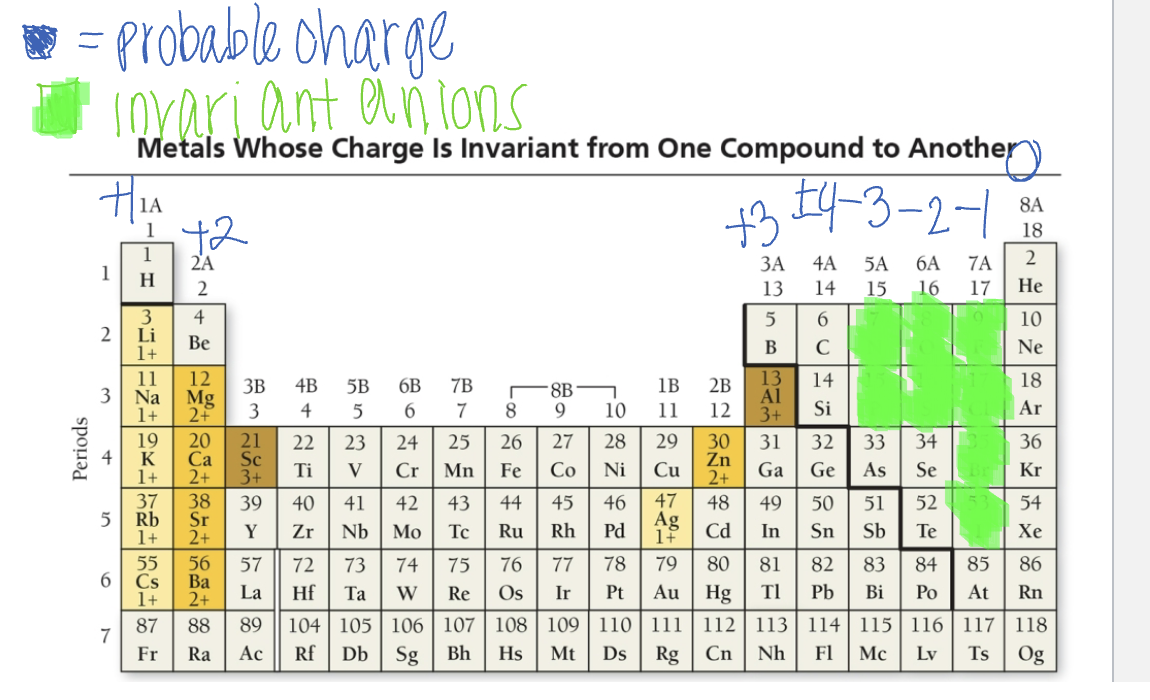

Invariant: metals whose charge remains the same when forming an ionic bond

alkali except for hydrogen and Fr (1+), alkaline earths except for Be and Ra (2+), zinc (2+), Al (3+) and Ag (1+)

Variant: metals that can vary in charge from one compound to another

transition metals, inner transition metals, and p-block metals

Binary compounds: contain only two different elements.

naming of binary ionic invariant compounds:

name of cation (metal) + base name of anion (nonmetal) + ide

naming of binary ionic variant compounds:

name of cation is followed by a roman numeral (in parentheses) that indicates the charge of the metal in that particular compound + base name of anion (nonmetal) + ide

example: Cu2O → copper (II) oxide

example: CuO → copper (I) oxide

Developing Formulas from Names of Invariant Charge:

1) write each species in name as a neutral atom

2) determine the charge that they would have once they fill their valence shell

3) cross # portion of charges

example: Calcium Chloride

Ca, Cl

Ca 2+, Cl- (cross)

CaCl2

example: Magnesium Oxide

Mg, O

Mg 2+, O2- (cross)

MgO (simplify the 2,2)

example: sodium nitride

Na, N

Na 1+, N 3-

Na3N

Developing Formulas from Names of Variant Charge:

Example: Cu2O

to name this, uncross the subscripts to get the charges

Cu 1+, O2-

Copper (I) Oxide

Example: CuO

Cu 2+, O 2-

Copper (II) Oxide

Example: Co2O3

Co 3+, O 2-

Cobalt (III) Oxide

Example: CoO2

Co 4+, O 2-

Cobalt (IV) Oxide

Example: PdCl2

Pd 2+, Cl-

Palladium (II) Chloride

Example: FeN

Fe 1+, N 1-

Fe 3+, N 3-

Iron (III) Nitride

Iron (III) Sulfide

Fe, S

Fe 3+, S 2-

Fe2S3

Titanium (IV) Carbide

Ti, C

Ti 4+, C 4-

TiC

Gold (III) Iodide

Au, I

Au 3+, I -

AuI3

Common Anions to Memorize:

F-

Cl-

Br-

I-

O2-

S2-

N3-

P3-

Metals with Variant Charge to Memorize:

Cr 2+ - Chromium (II)

Cr 3+ - Chromium (III)

Fe 2+ - Iron (II)

Fe 3+ - Iron (III)

Co 2+ - Cobalt (II)

Co 3+ - Cobalt (III)

Cu + - Copper (I)

Cu 2+ - Copper (II)

Sn 2+ - Tin (II)

Sn 4+ - Tin (IV)

Hg2 2+ - Mercury (I)

Hg 2+ - Mercury (II)

Pb 2+ - Lead (II)

Pb 4+ - Lead (IV)

Polyatomic Ions:

Ions that contain more than one atom

Polyatomic ion will replace the metal (in the case of ammonium, NH4+) or replace the nonmetal

Oxyanions: most polyatomic ions are oxyanions, anions containing oxygen and another element

the one with more oxygen atoms has the ending -ate

No3- is nitrate

the one with fewer oxygen atoms has the ending -ite

No2- is nitrite

If there are more than two ions in the series, then the prefixes hypo- (less than) and per- (more than) are used

Hypochlorite: ClO -

Chlorite: ClO2 -

Clorate: Clo3 -

Perchlorate: ClO4 -

Polyatomic Ions to Memorize:

Acetate: C2H3O2 -

Carbonate: CO3 2-

Hydrogen Carbonate (bicarbonate): HCO3 -

Hydroxide: OH -

Nitrite: NO2 -

Nitrate: NO3 -

Chromate: CrO4 2-

Dichromate: Cr2O7 2-

Phosphate: PO4 3-

Hydrogren Phosphate: HPO4 2-

Dihydrogen Phosphate: H2PO4 -

Ammonium: NH4 +

Perflourate: FO4 -

Flourate: FO3 -

Flourite: FO2 -

Hypoflourite: FO -

Permanganate: MnO4 -

Sulfite: SO3 2 -

Hydrogen sulfite (or bisulfite): HSO3 -

Sulfate: SO4 2-

Hydrogren sulfate (or bisulfate): HSO4 -

Cyanide: CN -

Peroxide: O2 2-

Oxyanions to Memorize:

Hypochlorite: ClO -

Chlorite: ClO2 -

Chlorate: ClO3 -

Perchlorate: ClO4 -

Perbromate: BrO4 -

Periodate: IO4 -

Bromate: BrO3 -

Iodate: IO3 -

Bromite: BrO2 -

Iodite: IO2 -

Hypobromite: BrO -

Hypoiodite: IO -

Naming Binary Ionic Compounds with Polyatomic Ions

uncross the subscripts to get the charges

Example: Na2(SO4)

Na 2+, (SO4) 2-

Na(SO4)

Sodium Sulfate

Example: Pb(NO3)2

Lead, (NO3) -2

Lead (II) Nitrate

Example: (NH4)2S

Ammonium, Sulfur

Ammonium +2, Sulfur -2

Ammonium Sulfide

Example: Mn(CO3)

Manganese, Carbonate (2-)

Manganese (II) Carbonate

Example: Copper (II) Hydroxide

Cu 2+, OH -

Cu(OH)2

Covalent Compounds: Formulas and Names

The formula for a covalent compound cannot readily be determined from its constituent elements because the same combination of elements may form many different molecular compounds, each with a different formula.

example of N and O: NO, NO2,N2O, N2O3, N2O4, N2O5

Covalent compounds are composed of two or more nonmetals

Naming Covalent Compounds:

Write the name of the element with the smallest group first

if the two elements lie in the same group, then write the element with the greatest row number first

The prefixes given to each element indicate the number of atoms present

prefix + name of first element + prefix + base name of 2nd element + ide

Prefixes for Covalent Compounds to Memorize:

Mono = 1

Di = 2

Tri = 3

Tetra = 4

Penta = 5

Hexa = 6

Hepta = 7

Octa = 8

Nona = 9

Deca = 10

Acids:

Acids are molecular compounds that release hydrogen ions (H+) when dissolved in water.

Acids are composed of hydrogen, usually written first in their formulas, and one or more nonmetals, written second.

Binary acids have H+ cation and nonmetal anion

Hydro + base name of nonmetal + -ic + acid

Example: HCl

Hydrogen, Chlorine

Hydrochloric Acid

Example: H2Se

Hydrogren, Selenium

Hydroselenic Acid

Oxyacids have H+ cation and polyatomic anion

base name of oxyanion + -ic + acid

Example: HNO3

Nitric Acid

Example: H2SO4

Sulfuric Acid

Acids - formula has H as first element

Binary acids contain only two elements

Oxyacids contain oxygen

Electronegativity: measure of how well an atom can attract an electron to itself