Economic Way of Thinking - 9. Price searching

How do price searchers find what they're looking for, and what happens when they find it?

The popular theory of price setting

The everyday explanation is a simple cost-plus-markup theory: Business firms calculate their unit costs and add on a percentage markup.

Most people just do it without being able to explain how it's done.

This theory can be doubted because it tells un nothing about the size of the markup.

The concept of marginal revenue

Marginal revenue is the additional revenue expected from an action under consideration.

The extra revenue from selling one more item.

To maximize net revenue, set a price that will enable you to sell all those units, but only those units, for which marginal revenue is expected to be greater than marginal cost.

The rest of the units adds more to costs than to revenue, because the price has to be lowered to sell more units.

Example: Ed Sike and the cinema tickets.

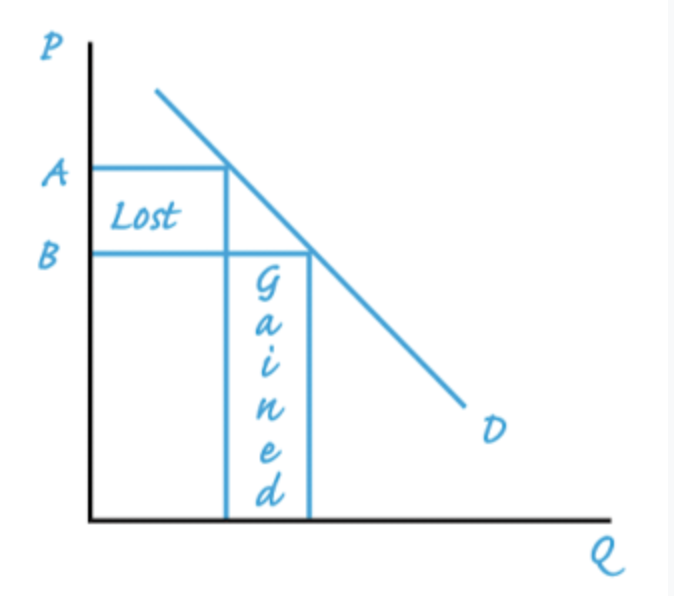

Lowering the price from A to B gains some revenue from additional sales, but also loses some revenue because all buyers now pay the lower price.

The price discriminator's dilemma

But by setting that price, there will be some customers lost who are willing to buy.

Example: Ed will be left with empty seats and people who want to go see the movie.

Profit can be made if the owner can reduce the price only to those new customers, without reducing it to those who are willing to pay more.

Example: Ivy Leagues reduce costs only to some by offering "scholarships".

The goal is to find low-cost techniques for distinguishing high-price from low-price buyers, and then to offer reduced prices exclusively to those who otherwise won't purchase the product.

Attract some additional business from groups that are more sensitive to prices, but without lowering the price to everyone.

Resentment and rationale

This can arouse indignation on the part of those who aren't offered the discount prices.

Three conditions for successful price discrimination: The seller must be able to

distinguish buyers with different elasticities of demand

prevent lowprice buyers from reselling to high-price buyers

control resentment

Example: higher prices for dinner than for lunch.

You can legitimately view price discrimination as a form of cooperation between sellers and buyers, which occurs when transaction costs are sufficiently low.

Cost-plus-markeup reconsidered

So how do price searchers find what they’re looking for?

estimating the marginal cost and marginal revenue

determining the level of output that will enable them to sell all those units of output, and only those units for which marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost

setting their price or prices so that they can just manage to sell the output produced.

equating marginal cost and marginal revenue is the outcome of the competitive market process

The complexity and uncertainty of the price searcher’s task help explain the popularity of the cost-plus-markup theory.

Summary

Price searchers are looking for pricing structures that will enable them to sell all units for which marginal revenue exceeds marginal cost.

The popularity of the cost-plus-markup theory of pricing rests on its usefulness as a search technique, and the fact that people often cannot correctly explain processes in which they regularly and successfully engage.

A crucial factor for the price searcher is the ability or inability to discriminate: to charge high prices for units that are in high demand and low prices for units that would not otherwise be purchased, without allowing the sales at lower prices to “spoil the market” for high-price sales.

A rule for successful price searching often quoted by economists is this: Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost. This means: Continue selling as long as the additional revenue from a sale exceeds the additional cost. Skillful price searchers are people who know this rule (even when they don’t fully realize they’re using it) and who also have a knack for distinguishing the relevant marginal possibilities. The possibilities are endless, which helps to make price theory a fascinating exploration for people with a penchant for puzzle solving.

Sellers in the real world don’t have precisely defined demand curves from which they can derive marginal-revenue curves to compare with marginal-cost curves. Working with such curves is nonetheless a good exercise for a student who wants to begin thinking systematically about the ways in which competition affects the choices people make and the choices they confront.