Chapter 15: Early Renaissance in Italy: Fifteenth Century

Key Notes

- Time Period: 1400–1500

- Takes place in the courts of Italian city-states: Ferrara, Florence, Mantua, Naples, Rome, Venice, and so on.

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

- Renaissance art is influenced by the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

- Cultural interactions

- There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

- Materials and Processes

- The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism

- Audience, functions, and patron

- There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

- Theories and Interpretations

- Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

- There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

Historical Background

- Italian city-states were controlled by ruling families who dominated politics

- These princes were lavish spenders on the arts, and great connoisseurs of cutting-edge movements in painting and sculpture.

- They embellished their palaces with the latest innovative paintings by artists such as Lippi and Botticelli.

- They commissioned architectural works from the most pioneering architects of the day.

- Princely courts eventually shifted from religious to secular concerns in a humanistic spirit.

- Humanism: an intellectual movement in the Renaissance that emphasized the secular alongside the religious.

- Humanists were greatly attracted to the achievements of the classical past, and stressed the study of classical literature, history, philosophy, and art

Patronage and Artistic Life

- The patrons of this time dictated the quantity of gold used on altarpieces and which family members were to be shown in paintings.

- Great families often had their own chapel in the local church.

- These churches' mysticism was enhanced by muralists.

- Quattrocento: the 1400s, or fifteenth century, in Italian art

Early Renaissance Architecture

- Renaissance architecture requires order, clarity, and light.

- Gothic churches' gloom, mystery, and sacredness were barbarous.

- Wide windows, minimal stained glass, and vibrant wall murals replaced it.

- Renaissance architecture emphasizes geometric designs, yet all buildings require mathematics to support their technical principles.

- Vitruvius' ideal proportions created harmony.

- Humanistic values were reflected in Florentine Renaissance church interior ratios and proportions.

- Unvaulted naves with coffered ceilings reminded Early Christianity.

- Thus, the crossing is twice the nave bays, the nave twice the side aisles, and the side aisles twice the side chapels.

- The nave is two-thirds arches and columns.

- As in Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel, the nave's white and gray marble floor patterns emphasize this logic.

- Alberti's Palazzo Rucellai and other Florentine buildings feature austere, three-story façades.

- The first level is usually for public use and business.

- A sturdy string course marks the ceiling and floor of the second storey, which rises light.

- Roman temple-style cornices top the third story.

- Mullion: a central post or column that is a support element in a window or a door

- Orthogonal: lines that appear to recede toward a vanishing point in a painting with linear perspective

➼ Pazzi Chapel

Details

- Designed by Filippo Brunelleschi

- Basilica di Santa Croce

- Designed 1423; Built 1429–1461,

- A masonry,

- Found in Florence, Italy

Form

- Two barrel vaults on the interior; small dome over crossing; pendentives support dome; oculus in the center.

- Interior has a quiet sense of color with muted tones that is punctuated by glazed terra cotta tiles.

- Use of pietra serena (a grayish stone) in contrast to whitewashed walls accentuates basic design structure.

- Pietra serena: a dark-gray stone used for columns, arches, and trim details in Renaissance buildings

- Inspired by Roman triumphal arches.

- Ideal geometry in the plan of the building.

Function

- Chapter house: a meeting place for Franciscan monks; bench that wraps around the interior provides seating for meetings.

- Rectangular chapel with an apse and an altar attached to the church of Santa Croce, Florence.

Attribution

- Attribution of portico by Brunelleschi has been recently questioned;

- The building may have been designed by Bernardo Rossellino or his workshop.

Patronage

- Patrons were the wealthy Pazzi family, who were rivals of the Medici.

- The family coat-of-arms, two outward facing dolphins, is placed at the base of each pendentive on the interior.

Image

➼ Palazzo Rucellai

Details

- Designed by Leon Battista Alberti

- c. 1450, stone,

- A masonry

- Found in Florence, Italy

Form

- Three horizontal floors separated by a strongly articulated stringcourse; each floor is shorter than the one below.

- Pilasters rise vertically and divide the spaces into squarish shapes.

- An emphasized cornice caps the building.

- Square windows on the first floor; windows with mullions on the second and third floors.

- Rejects rustication of earlier Renaissance palaces; used beveled masonry joints instead.

- Benches on lower level connect the palazzo with the city.

Function

- City residence of the Rucellai family.

- The building format expresses classical humanist ideals for a residence:

- the bottom floor was used for business;

- the family received guests on the second floor;

- the family’s private quarters were on the third floor;

- the hidden fourth floor was for servants.

Context

- The articulation of the three stories links the building to the Colosseum levels, which have arches framed by columns:

- the first floor pilasters are Tuscan (derived from Doric);

- the second are Alberti’s own invention (derived from Ionic);

- the third are Corinthian.

- Original building:

- Five bays on the left, with a central door.

- Second doorway bay and right bay added later.

- Eighth bay fragmentary: owners of house next door refused to sell, and the Palazzo Rucellai never expanded.

Patronage

- Patron was Giovanni Rucellai, a wealthy merchant.

- Rucellai coat-of-arms, a rampant lion, is placed over two second-floor windows.

- Friezes contain Rucellai family symbols: billowing sails.

Image

Fifteenth Century Italian Painting and Sculpture

- Linear perspective, which some experts believe the Romans used, is the most distinctive feature of Italian Renaissance art.

- In the early fifteenth century, Filippo Brunelleschi created perspective while sketching the Florence Cathedral Baptistery.

- Some painters were obsessed with perspective, presenting things and people in proportion, unlike medieval painting, which emphasized humans.

- Linear perspective was quickly adopted by pre-Traditional artists.

- The artists used trompe l'oeil to purposely deceive the viewer.

- Trompe l’oeil: (French, meaning “fools the eye”) a form of painting that attempts to represent an object as existing in three dimensions, and therefore resembles the real thing.

- By the end of the fifteenth century, portraits and mythical subjects had replaced religious paintings, expressing humanist ideas.

- Humanism and Greco-Roman classics revive interest in genuine Greek and Roman sculptures.

- Medieval painters saw old naked glory as heathen.

- Donatello's David begins the century-long renaissance of nudity in life-size sculpture in Florence.

- Increased anatomy study leads to nudity.

- Nude sketches of heroes are cast in stone and metal.

- Some painters display tremendous physical interplay of shapes in their twisting motions and straining muscles.

- Bottega: the studio of an Italian artist

- Perspective: depth and recession in a painting or a relief sculpture.

- Objects shown in linear perspective achieve a three-dimensionality in the two-dimensional world of the picture plane.

- Lines, called orthogonals, draw the viewer back in space to a common point, called the vanishing point.

- Paintings, however, may have more than one vanishing point, with the orthogonals leading the eye to several parts of the work.

- Landscapes that give the illusion of distance are in an atmospheric or aerial perspective.

➼ Madonna and Child with Two Angels

Details

- Painted by Fra Filippo Lippi

- c. 1465

- Tempera on wood

- Found in Uffizi, Florence

- Madonna: the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ

Content and Symbolism

- Symbolic landscape

- Rock formations symbolize the Christian Church.

- City near Madonna's head is the Heavenly Jerusalem.

- Pearl motif: seen in headdress and pillow as products of the sea.

- Pearls used as symbols in scenes of the Incarnation of Christ.

Context

- Mary is seen as a young mother.

- Model may have been the artist’s lover.

- Landscape inspired by Flemish painting.

- Scene depicted as if in a window in a Florentine home.

- Humanization of a sacred theme; there is a sense of domestic intimacy.

- Lippi was a monk, as indicated by the word “Fra” that precedes his name; he was working in a Carmelite monastery under the patronage of the Medici.

Image

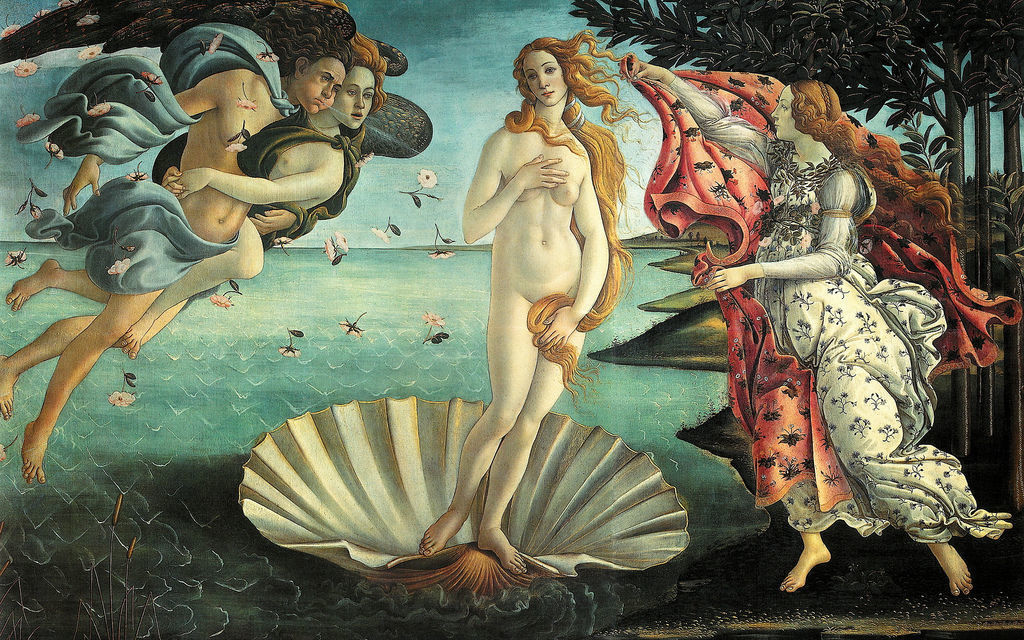

➼ Birth of Venus

Details

- Painted by Sandro Botticelli

- c. 1484–1486

- Tempera on canvas

- Found in Uffizi, Florence

Form

- Crisply drawn figures.

- Landscape flat and unrealistic; simple V-shaped waves.

- Figures float, not anchored to the ground.

Content

- Venus emerges fully grown from the foam of the sea with a faraway look in her eyes.

- Roses scattered before her; roses created at the same time as Venus, symbolizing that love can be painful.

- On the left: Zephyr (west wind) and Chloris (nymph).

- On the right: handmaiden rushes to clothe Venus.

Context

- Medici commission; may have been commissioned for a wedding celebration.

- Painting based on a popular court poem by the writer Poliziano, which itself is based on Homeric hymns and Hesiod’s Theogony.

- A revival of interest in Greek and Roman themes can be seen in this work.

- Earliest full-scale nude of Venus in the Renaissance.

- Reflects emerging Neoplatonic thought.

- Neoplatonism: a school of ancient Greek philosophy that was revived by Italian humanists of the Renaissance

Image

➼ David

Details

- Sculpted by Donatello

- c. 1440–1460

- Made of bronze

- Found in National Museum, Bargello, Florence

Form

- First large bronze nude since antiquity.

- Exaggerated contrapposto of the body.

- Sleekness of the black bronze adds to the femininity of the work.

- Androgynous figure; homoerotic overtones.

Function

- Life-size work, probably meant to be housed in the Medici palace courtyard; not for public viewing.

Content

- The work depicts the moment after David slays the Philistine Goliath with a rock from a slingshot; David then decapitates Goliath with his own sword.

- David contemplates his victory over Goliath, whose head is at his feet; David’s head is lowered to suggest humility.

- Laurel on David’s hat indicates he was a poet; the hat is a foppish Renaissance design.

Context

- David symbolizes Florence taking on larger forces with ease; perhaps Goliath would have been equated with the Duke of Milan.

- Nothing is known of its commission or patron, but it was placed in the courtyard of the Medici palace in Florence.

- Modern theory alleges that this is a figure of Mercury, and that the decapitated head is of Argo;

- Mercury is the patron of the arts and merchants, and therefore an appropriate symbol for the Medici.

Image