Memory

Memory is the cognitive process by which we retain and recall information about events that have happened in the past.

Memory Processes

Coding: The format in which information is stored in the various memory stores. (Baddeley et al 1966)

Capacity: How many items can be held in a particular memory store. (Miller 1956)

Duration: The length of time the memory store holds information. (Peterson and Peterson 1959)(Bahrick et al 1975)

Retrieval: To access information from a memory store in a structured format.

Baddeley et al 1966

Aim: to investigate encoding of STM and LTM.

Procedure: Participants were given acoustically similar words or dissimilar words to learn in order and asked to recall the words in the correct order. Participants were given semantically similar words or dissimilar words and asked to recall the words in the correct order after 20 minutes.

Results: In immediate recall, the recall of acoustically similar words was worse than the dissimilar list. This suggests that STM is encoded acoustically as it was easier to mix the encoding of these words up. In the delayed recall, the recall of semantically similar words was worse than the dissimilar list. This suggests that LTM is encoded semantically as it is easier to mix the encoding of these words up.

Strength: The study was standardised and can be replicated, presenting high reliability. It has beneficial implications for real-life scenarios; for instance, students can use these findings to strategize their revision techniques.

Weakness: Ethnocentric as it was carried out on British students, therefore the research does not consider cross-culture differences and limits the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, the sample included 72 participants which is not representative of the population. Low ecological validity as it lacks mundane realism and it was conducted in a lab setting.

Miller (1956)

Aim: to investigate the capacity of STM.

Results: Participants were able to recall, on average, 7+-2 if asked to immediately recall. This suggests that the capacity of STM is Miller’s magic number, 7+-2.

Strength: Reliable as his results were supported by Jacobs’ research which found that the mean letter span was 7.3 and the mean digit span was 9.3.

Weakness: More recent studies have found that Miller may have over-exaggerated the capacity of STM. Cowan (2001) concluded that the capacity was more similar to 4 chunks. Miller also had a lack of control over confounding variables which may have contributed to this inaccurate estimate.

Peterson and Peterson (1959)

Aim: to investigate the duration of STM.

Procedure: Participants were given a trigram (without vowels to avoid any easy words) to recall after intervals of 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 or 18 seconds. To prevent reversal, participants were asked to count backwards in threes or fours from a given number.

Results: After 3 seconds, 80% of the trigrams were recalled correctly, but after 18 seconds less than 10% of the trigrams were recalled correctly. This suggests that the duration of STM is around 18 seconds long without rehearsal.

Strength: Increased internal validity as extraneous variables were controlled. Participants had to count backwards requiring deeper level of processing, the trigrams had no vowels to avoid any common words.

Weakness: Lack of ecological/external validity since the information was not meaningful. Lacks mundane realism as the stimuli was artificial. The study was originally held in a laboratory therefore cannot be generalised, furthermore cannot be generalised as the sample was all white males.

Bahrick (1975)

Aim: to investigate the duration of LTM.

Procedure: Participants, aged between 17 and 74, were given a recognition test to identify photos from their High School Yearbook.

Results: Even the oldest participants were accurate most of the time in identifying the people from their photos, suggesting the duration of information in LTM is potentially forever.

Strength: High external validity since meaningful information was recalled (Shepard (1967) showed recall rates were far lower when meaningless stimuli were used). This also has high mundane realism.

Weakness: Confounding variables are not controlled in real-life studies. The sample was unrepresentative therefore cannot be generalised to many other populations.

Exam Question

“Evaluate studies into coding/capacity/duration.” [6 marks]

Baddeley et al (1966) investigated the coding of short term memory (STM) and long term memory (LTM) by giving participants a list of 10 words to learn and recall. One group were shown acoustically similar words to recall immediately and semantically similar words to recall after 20 minutes, another group were shown acoustically dissimilar words for immediate recall and semantically dissimilar words for delayed recall. A weakness of this is the lack of mundane realism due to the artificial stimuli. It is highly unlikely people are expected to memorise a list of words which may or may not be acoustically or semantically similar. The study found that immediate recall of the acoustically similar words was worse than the list of dissimilar words suggesting STM is encoded acoustically as it was easier to mistake those types of words. Similarly, as it was easier to mistake the semantically similar words in the delayed recall, it is suggested that LTM is encoded semantically. A strength of this study is the real-life applications it has, especially for students in terms revision techniques.

Miller (1956) conducted research into the capacity of STM by asking participants to immediately recall a sequence of letters or numbers which increased by one with each trial. He concluded that the capacity of STM is 7+-2 ‘bits’ of information which supported Jacobs’ findings of 7.3 to 9.3 - this strengthens the research. On the other hand, the study is weakened by more recent research by Cowan (2001) which found that Miller’s number may be an over-exaggeration. Cowan concluded that the capacity of STM is closer to 4 chunks of information. Furthermore, Miller also had a lack of control over confounding variables which may have contributed to the possible inaccuracy of the results.

Peterson and Peterson (1959) conducted research into the duration of the short term memory (STM) store by presenting participants with three consonant trigrams which they had to memorise and recall. These trigrams did not contain vowels in order to avoid normal words, rendering the trigram meaningless. The results found that 80% of the trigrams were accurately recalled after 3 seconds, but only 10% of trigrams were accurately recalled after 18 seconds, suggesting that the duration of STM is 18 seconds. One strength of the study is the meaningless trigrams not reflecting normal words as it reduces the effect of some extraneous variables - participants could not simply recall an easy word. However, it is weakened as the stimuli was artificial and lacked mundane realism, in reality people do not need to remember meaningless trigrams.

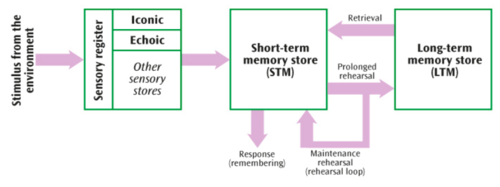

Multi Store Model

Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) explained memory as having three different unitary stores: Sensory store (sensory register), Short-term memory (STM), Long-term memory (LTM).

Information that arrives at our senses is briefly held in the sensory register but fades as quick as it was to arrive unless something is done. Information is then passed to the STM for encoding, if it isn’t rehearsed then it can be forgotten. If rehearsed the information can then be transferred into the LTM.

Rehearsal

Maintenance: repeating information to keep it in STM

Prolonged: rehearsal of information to move it from STM to the LTM

Elaborative: semantically process information into LTM

Sensory Register

Capacity: unlimited

Coding: sense-specific

Duration: >0.5 seconds

Short Term Memory

Capacity: 7+-2 items

Coding: acoustically

Duration: max 18-30 seconds

Long Term Memory

Capacity: unlimited

Coding: semantically

Duration: unlimited

Multi Store Model: Evaluation

Sperling (1960)

Aim: to investigate the capacity of sensory register

Procedure: A visual array of 12 letters was shown to participants for 50milliseconds. Participants were required to report the letters, typically they were able to report 4 out of 12 letters. Sterling suspected that more than 4 items could be stored in the sensory register but it faded rapidly before it could be reported aloud. He tested this by presenting the participants with a tone of high, medium, or low pitch after the presentation of the letter array. Participants were then required to report the letters they had seen from the top, middle or bottom row depending on the sound they heard.

Results: When asked to report the whole grid, participants recall was poorer (42%). When asked to only give one row, participants recall was better (75%.) This suggests that all the letters were stored in the memory and were available to be recalled but only for a very short while after display. Large amounts of information can be stored but it fades rapidly, ¼ second following presentation.

Strength: Lab experiment with high levels of control and is easily replicated.

Weakness: Lack of ecological validity as it is artificial.

Patient HM

Case study for MSM.

Patient HM suffered damage to the hippocampus as a result of a surgery for epilepsy. As a result, his episodic memory/STM was severely impaired - he could not remember past events. However, his semantic memory was relatively intact. For example, he knew the concept of a dog but could not remember petting a dog 30 minutes ago. His IQ was tested before and after surgery - he scored 112 points after his surgery compared to 104 points before his surgery suggesting his ability in arithmetic had apparently improved, the only behaviour that seemed to be affected was his memory.

Support: The case study of HM supports MSM as it is evidence for memory not being a unitary store. It suggests that the hippocampus is needed to transfer memory from the STM to the LTM.

Limitation: The case study of HM provides evidence that MSM is an incomplete model as his procedural memory was not impaired (he retained his memory of skills). He could also recall some events from before his surgery but could not form any new long-term memories. Milner (psychologist) observed his performance of tracing a star outline from only seeing a reflection over a period of a few days. Each time he performed the task he had no memory of ever having done it before, but his performance kept improving. His procedural long term memory had not been affected.

Patient Clive Wearing

Case study for MSM.

Clive Wearing suffered damage to his hippocampus after a viral infection (herpes encephalitis). CW had difficulty recalling events which happened to him in the past, however his procedural memory was relatively intact (he could still play the piano as a professional musician). He could not “make new memories” but could remember some details about events from before his infection.

Support: CW supports the MSM as it suggests that these types of memory are stored in different regions of the brain. It supports MSM as it is evidence for a clear difference between STM and LTM - damaged episodic memory/STM and unaffected procedural memory/LTM.

Limitation: CW provides evidence that limits MSM as he is evidence the model is incomplete. CW is evidence that the LTM is not a unitary store as his procedural memory was intact but his episodic memory was severely damaged.

Patient KF (Shallice and Warrington (1970))

Case study for MSM.

Patient KF had suffered a motorcycle accident when he was 17 years old which damaged his left parieto-occipital region. After his accident, his STM was reduced drastically with only being able to hold about 2 chunks/units of information compared to 4. He had trouble with his STM acoustically but not visually suggesting maybe only the phonological loop had been damaged. Studies on KF found that his LTM abilities were normal.

Support: KF supports the MSM as it is evidence for STM and LTM being separate stores.

Limitation: KF suggests that STM is not a unitary store as only his acoustic STM was impaired and his visual STM remained intact.

Case Study Evaluation

Strengths

Provides rich, in depth data

Suggests directions for further research

Allows investigation that might be difficult or unethical to do in other ways.

Biometric data and neuroimaging, eg brain scans, are objective.

Weaknesses

Correlation does not mean causation

Cannot be generalised to wider population - idiographic approaches (study of an individual) tried to be applied nomothetical (to wider population)

Cannot be replicated therefore cannot check reliability

Exam Question

“Choose one strand of evaluation of the MSM to discuss and develop” [6 marks]

The Multi-Store Model (MSM) suggests that memory is divided into 3 unitary stores; sensory register, Short-term memory (STM), and Long-term memory (LTM). The MSM is successful in identifying the different memory stores however it is an incomplete theory as it is too simplistic. The case of Clive Wearing (CW) supports the MSM as it provides evidence for a clear division between STM and LTM stores. CW’s LTM remained intact shown in his retained memory of how to play piano professionally yet his STM was damaged shown in how he could not remember his wife leaving the room for a minute. However, the case study of CW can also be used as a limitation of the MSM. CW demonstrates how LTM is not an unitary store because his episodic memory was damaged (for example he could not recall events that happened to him since the virus), yet his procedural and semantic memory was unimpaired (for example he retained the ability to walk, play piano, and remember who his wife was). This weakens the MSM as it is evidence of LTM not being an unitary store suggesting the model in too simplistic. A strength of using the case study is that is provides rich and in-depth qualitative data. On the other hand, the use of case studies is weakened by the fact they cannot be ethically replicated therefore the reliability of the qualitative data cannot be checked.

Long Term Memory

Semantic Memory: Memory for facts and knowledge/concepts. Semantic memories typically start as episodic memories but progressively lose their association with particular events and only the knowledge remains. They are not time-stamped but are more than facts. In some circumstances, it can be hard to distinguish a semantic memory from episodic memories. For example, the meaning of words, the capital of England is London.

Episodic Memory: Personal memories of events. These memories usually include details of an event, the context in which the event took place and emotions associated with the event. They are time-stamped and conscious effort is often needed to recall them. For example, your last birthday, wedding day, first day of school or work.

Procedural Memory: Memory of how to do things. These memories require a lot of repetition and practice, unlike semantic and episodic memory procedural memory is implicit. Implicit means that it is harder to explain them even if the action is easy to perform. Procedural memories are automatic and have unconscious effort. For example, riding a bike, swimming, writing.

Emotional Condition: Events that cause strong emotions can condition people to recognise stimuli quickly and react accordingly. For example, people who are afraid of thunder - lightning will trigger their conditioning, which could result in them immediately covering their ears and shutting their eyes.

Long Term Memory: Evaluation

Patient HM

Different types of LTM

As a result of damage to his hippocampus, HM’s episodic memory was severely impaired. However, his semantic memory was relatively intact. For example, he knew the concept of a dog but could not remember petting a dog 30 minutes ago.

Support:The case study of HM supports different forms LTM as it is evidence for memory not being a unitary store and suggests they are stored in different locations of the brain.

Limitation:Limitations of case studies. Generalisability, reliability, and correlation does not mean causation.

Clive Wearing

Different types of LTM

Clive Wearing suffered damage to his hippocampus after a viral infection (herpes encephalitis). CW had difficulty recalling events which happened to him in the past, however his procedural memory was relatively intact (he could still play the piano as a professional musician). He could not “make new memories” but could remember some details about events from before his infection.

Support: CW supports different forms of LTM as it is evidence for LTM not being a unitary store and suggests they are stored in different locations.

Limitation: Limitations of case studies. Generalisability, reliability, and correlation does not mean causation.

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging evidence objectively suggested that different types of memory are stored in different regions of the brain. Tulving et al (1994) asked participants to preform various memory tasks whilst their brains were scanned using a PET scanner. Their results showed that when episodic memories were recalled the left prefrontal cortex was activated and when semantic memories were recalled the right prefrontal cortex was activated.

Cohen and Squire (1980): suggested that LTM is simply split into declarative and non-declarative.

Real World Application (RWA): Psychologist can improve the quality of life for those individuals suffering from amnesia, Belleville et al. Education may improve with this knowledge and memory techniques can improve with understanding of memory.

Belleville et al: They noted that mild cognitive impairments most commonly affect episodic memories. With an increased understanding of episodic memory improved, increasingly targeted treatments for mild cognitive impairments.

“Choose two opposing areas of LTM evaluation and discuss their contrasts.” [6 marks]

Clive Wearing suffered herpesviral encephalitis that left parts of his brain damaged affecting his memory. His episodic memory (the memory of personal events) was serenely damaged yet his procedural memory (the memory of how to do things) was unimpaired. This was shown through how he could still remember how to play piano professionally yet could not recall his wife leaving the room for a minute. Clive Wearing is evidence for a clear division of LTM into episodic and procedural memory. This suggests that LTM is not an unitary store, this supports the different forms of LTM as if it was an unitary store both episodic and procedural memory would be affected. It also suggests that episodic and procedural memory are stored in different regions of the brain.

On the other hand, case studies of patients, like Clive Wearing, suffering from brain damaged are very limited. One limitation of case studies is generalisability. For example, Clive Wearing’s results cannot be generalised to the population as they have not suffered from brain damage due to herpes encephalitis. Even though case studies provide rich, in-depth qualitative data, the results are idiographic and cannot be applied through a nomothetical approach. Another limitation is that case studies cannot ethically be replicated. It would be unethical to infect another patient with the same virus as CW to test the reliability of his results regarding LTM. Furthermore, it cannot be proved that the correlation is the causation of the result, it cannot be proved the virus damaged Clive Wearing’s episodic memory. This is another limitation against the evidence of different forms of LTM.

Working Memory Model

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) suggest a more complex and dynamic STM than the multi-store model suggests. The active system has several connected parts and can do things simultaneously however two of the same type of task would result in poor performance. B&H suggested a multi-component WMM comprising of four components, to represent the form of processing the being carried out. In this model the LTM is simply a passive store.

Central Executive: Described as an “attention process,” the role of the CE is to allocate tasks to the 3 slave systems. It has a limited capacity and it involves reasoning and decision-making tasks. The coding of CE is modality free, it is not limited to a specific sense.

Phonological Loop: Processes auditory information and the loop allows for maintenance rehearsal as it is made up of the phonological store (holds words) and articulatory loop. The articulatory process which holds the words and silently repeats them. Its capacity is 2 seconds of information.

Visuo-spatial sketch Pad: The Visuo-spatial sketch pad combines the visual and spatial information. The VSS is divided into the inner scribe and visual cache. Logie (1995)’s subdivisions are the store (visuo-cache) and the inner scribe for spatial relations. The capacity is believed to be around 4-5 chunks of information.

Episodic Buffer: This integrates all types o data processed by the other stores and is describes as the storage component of the CE, it is also crucial for linking the STM to the LTM. This has no/low capacity, it holds the most recent activated memory and provides us with a sense of chronology. The coding of the EB is modality free, it is not limited to a specific sense.

Dual-task performance: Two tasks performed at the same time. If the tasks require only one store then performance is poor than when completed separately. If the tasks require two different stores then performance would be unaffected.

Esling and Demasio

Working Memory Model: Evaluation

Baddeley and Hitch (1976) Dual Tasks

Aim: to test the idea of more than one component in the working memory.

Procedure: Task 1 required participants to answer true or false to a statement, eg. B is followed by A - BA. This occupied the Central Executive. At the same time, participants had to complete task 2, which was one of three different “tasks.”

Repeat ‘THE’ over and over again, occupying the articulatory loop.

Say random digits out loud, occupying both the articulatory loop and the Central Executive.

Not required to complete a second task.

Results: When task 1 was combined with version 1 or 3 of task 2, performance was unaffected. When task 1 was combined with version 2 of task 2, performance speed dropped significantly. This shows that doing two tasks that required the same component of memory causes difficulty and when different components were required the performance of the task is not adversely affected.

Strength: This evidence suggests a clear division of STM into the phonological loop and visuo-spatial sketchpad. The experiment was highly controlled and has high internal validity.

Weakness: The tasks lack mundane realism.

4 tasks in dual tasks

Patient KF

Evidence for WMM

Patient KF had suffered a motorcycle accident which damaged his left parieto-occipital region. After his accident, his STM was reduced drastically with only being able to hold about 2 chunks/units of information compared to 4. He had trouble with his STM acoustically but not visually suggesting maybe only the phonological loop had been damaged. Studies on KF found that his LTM abilities were normal.

Support:KF supports the WMM as it is evidence for the phonological loop and visuo-spatial sketchpad being separate.

Limitation: Limitations of case studies.

Braver et al (1997)

Aim: to investigate whether the WMM is supported by neuroimaging.

Procedure: Participants were given tasks which engaged the CE whilst under a brain scan.

Results: Greater activity was found in the left prefrontal cortex which is likely to be the region associated with CE. As the tasks became harder, the activity in this area increased because the demands of the CE increased. Brain scanning techniques which engaged different subcomponents activated different areas of the brain, demonstrating physical representations of the component of the WMM.

Forgetting - Interference

Interference is when one memory disturbs the ability to recall another. This can explain forgetting or the distortion of memory. It can be either proactive or retroactive.

Proactive: Past information interfering with new memories hat are trying to be stored. For example remembering an ex’s name instead of your current partner’s name.

Retroactive: Recent/new information interfering with an old stored memories. For example, forgetting your old PIN when you get a new card.

The more similar the information the more likely there would be interference, drama and psychology vs biopsych and biology.

low ecological validity, not as bad in real life, baddeley and hitch counterpoint

Forgetting - Interference: Evaluation

Baddeley and Hitch (1977)

Aim: to investigate retroactive interference in everyday memory.

Procedure: Rugby union players were asked to recall the names of the teams they had played against earlier in the season. Some of the players had played every match in the season, the other group had missed some games due to an injury. The length of time from the start to the end of the season was the same for all players, it is not a contributing factor.

Results: Players who had played in all the matches could not recall all the teams they played against in the beginning. Injured players could recall more teams than the other players. This shows the result of retroactive interference, the new team names interfered with the memory of the old teams.

Strength: This supports the theory of retroactive interference as an explanation of forgetting. Baddeley and Hitch’s study used natural stimuli, demonstrating everyday interference.

Weakness: As it was a field experiment, the findings are harder to replicate meaning the reliability is difficult to test. However, lab studies have found similar results therefore this is not a major limitation of the study.

McGeoch and McDonald (1931)

Aim: To investigate interference when memories are similar

Procedure: Participants had to remember a list of 10 words until they could remember them with 100% accuracy. After, they learned a new list of words from one of 6 groups.

Group 1 - Synonyms

Group 2- Antonyms

Group 3 - Unrelated to the first list

Group 4 - Nonsense syllables

Group 5 - Three-digit numbers

Group 6 - No new list

Results: Group 1 had the worst recall whereas group 6 had the best recall. This suggests that interference is the strongest when memories are similar.

Strength: The study was a lab experiment which has high internal validity as it has high control over extraneous variables. The results can be replicated because of the same reason, allowing reliability to be tested. It also requires little time, meaning it is an efficient method to test the impact of similarity on interference.

Weakness: The short-time period between learning the list and its recall is a weakness as it does not reflect everyday life. Another weakness is that it lacks ecological validity - the results do not accurately depict what happens in reality. Furthermore, the stimuli is artificial meaning that the findings have low mundane realism.

Tulving and Psotka (1971)

Various studies including Tulving and Psotka argue that the loss of information may only be temporal. The theory only explains certain types of forgetting. This suggests that the theory is incomplete.

“Evaluation of Interference” [8 marks]

One strength of the theory of interference as an explanation of forgetting is that there are many lab studies which support the theory.

Forgetting - Retrieval Failure

Retrieval Failure is an explanation for forgetting due to an absence of correct retrieval cues.

“The greater the similarity between the encoding event and the retrieval event, the greater the likelihood of recalling the original memory.” Tulving

The Encoding Specificity Principle (ESP) can be explained by retrieval failure, which can be divided into context or state dependent forgetting.

Context-dependent forgetting: When external cues at the time of coding do not match those present at recall. This includes the environment.

State-dependent forgetting: When internal cues at the time of coding do not match those present at recall. This includes mood, physiological state ie drunk, high.

Category-dependent forgetting: Lack of organisation may inhibit memory.

Forgetting - Retrieval Failure: Evaluation

Godden and Baddeley (1975)

Aim: To investigate the effect of the environment on recall.

Procedure: 18 divers were asked to learn lists of 36 unrelated words of two or three syllables. There were 4 conditions:

Learnt on the beach, recalled on the beach

Learnt on the beach, recalled under water

Learnt under water, recalled on the beach

Learnt under water, recalled under water

Results: When the conditions were matched, recall was higher. This supports the ESP as it is evidence for greater recall when the coding and recall events are similar.

Strength: The results of the experiment support the theory of ESP and retrieval failure.

Weakness: Various situational variables were not controlled which could have affected the results. The sample only included divers from one club therefore the results lack generalisability. Demand characteristics may have affected the results due to the repeated measure design.

Carter and Cassaday (1998)

Aim: to investigate the effect of state on recall.

Procedure: Participants were given anti-histamine which has a mild sedative, drowsy effect. Participants then had to learn lists of words and passages of text and recall them. There were 4 conditions:

Learnt on the drug, recalled on the drug

Learnt on the drug, recalled in a normal state

Learnt in a normal state, recalled on the drug

Learnt in a normal state, recalled in a normal state.

Results: When the conditions were matched, recall was higher. This supports the ESP as it is evidence for greater recall when the coding state and recall state are similar.

Strength: The results of the experiment support the theory of ESP and retrieval failure.

Weakness: Lab studies use artificial stimuli meaning that the results lack ecological validity.

Research Support

Aggleton and Waskett (1999) recreated the smells of a museum in York which helped participants remember details about their visit accurately.

Goodwin et al (1969) investigated the effect of being drunk.

Baker et al (2004) investigated the effect of chewing gum.

Immediate recall was similar

After 24 hours was better

Darley et al (1973) investigated the effect of being stoned.

Baddeley (1997) argued against his own study, low ecological validity.

Real World Application

ESP and context/state dependent forgetting can be applied to cognitive interviews.

ESP Untestable

It cannot be tested whether the cue triggered recall first or recall was successful then the cue was seen. It is assumed that if recall is successful then the cue must have been encoded at the time of learning. If recall is unsuccessful then the cue was either not present when attempting to retrieve information or the cue was not encoded when the information was learnt. Nairn (2002) said this as a criticism, confirmation bias makes us believe they are linked.

“Discuss two opposing areas of evaluation for retrieval failure” [6 marks]

Misleading Information

Misleading Information is incorrect post-event information given to an eyewitness (EW). It may come in the form of leading questions, post-event discussion (PED), or even stereotyping.

Eyewitness Testimony

The use of eyewitnesses to give evidence in court concerning the identity of someone who has committed a crime. One study reported that there may be about 10,000 false convictions a year in the US due to the erroneous EWT.

As a result of psychological research, prosecutions are now unlikely to be brought on by EWT alone, and more use is made of DNA evidence and closed-circuit TV recordings. This is the Devlin Report.

Leading Questions

A question which, because of the way it is phrased, suggests a certain answer.

Loftus and Palmer (1974)

Aim: to investigate if leading questions affect the accuracy of recall.

Procedure: Participants were shown a film of a car accident and were asked about the speed of the car using different verbs. How fast was the car travelling when it hit, smashed, collided with the other car? After a week they were asked more questions including if they had seen any broken glass.

Results: The mean estimated speed for participants with the verb hit was 34mph. The mean estimated speed for participants with the verb smashed was 41 mph. 14% of participants with the verb hit reported seeing broken glass compared to 32% with the verb smashed. Out of the control group who did not have a leading question only 12% reported seeing broken glass.

The phrasing of a police officer’s question could affect how an EW recalls an event.

Response-bias Explanation: the phrasing of the question affects how the EW decides to answer but memory stays the same.

The wording of the question has no real effect on the participants’ memories, but it influences how they decide to answer.

EXAMPLE: the speed of the car. ‘Smashed’ encourages a higher speed estimate to be chosen, this can be unknowingly/subconsciously or knowingly/consciously (influencing the participant to lie).

Substitution Explanation: the wording of the questions changes the EW’s memory of the event, substituting it with a false one.

The wording of a leading question actually changes the participants memory of the clip,

EXAMPLE: seeing the broken glass.

Post-Event Discussion

This occurs when co-witnesses to a crime discuss the event with each other, leading to their EWT becoming contaminated. This is because they combine information from other witnesses into their own memories.

Gabbert et al (2003)

Procedure: Studied participants in pairs. Each participant watched a video of the same crime, but filmed from different points of view. This meant that each participant could see elements in the event that the other could not. For example, only one participant could see the title of a book being carried by a young woman. Both participants then discussed what they had seen before individually completing a test of recall.

Findings: The researchers found that 71% of the participants mistakenly recalled aspects of the event that they did not see in the video, but had picked up in the discussion. The corresponding figure in a control group, with no PED, was 0%.

Conclusion: They concluded that witnesses often go along with each other, either to win social approval, or because they believe the other witnesses are right and they are wrong. They called this phenomenon memory conformity.

Misleading Information: Evaluation

Real-World Application

Research into misleading information has important practical uses in the criminal justice system.

The consequences of inaccurate EWT can be very serious.

Loftus believes that leading questions can have such a distorting effect on memory that police officers need to verify careful about how they phrase their questions.

Psychologists are sometimes asked to act as expert witnesses in court trials and explain the limits of EWT to juries.

However, the practical application of EWT may be affected by issues with research.

In Loftus and Palmer’s study, participants were asked to watch film clips which is artificial.

This means that the experiment may lack generalisation beyond the research setting.

All the participants were American, a non-representative sample, reducing the population validity and generalisability.

Foster et al (1994) pointed out that what an EW remembers has important consequences in the real world, but in research it does not matter in the same way.

Participants may be less motivated to remember accurately.

This suggests that researchers are too pessimistic about the effects of misleading information. EWT may be more dependable than many studies suggest.

Research indicates that leading questions do distort EWT which has led to important policy changes.

The Devlin Report concluded that British juries should not convict someone where the only evidence is a single EW.

The report emphasised that a single EW account is not enough for a conviction, advocating for additional supporting evidence due to the potential inaccuracy of EWs.

As a result, police officers and lawyers are trained to avoid using leading questions, which undermine the reliability of EWT, aiming to ensure a fairer judicial system and reduce wrongful convictions.

Research Evidence

There is evidence against the substitution explanation.

A limitation of substitution explanation is that EWT is more accurate for some aspects for an event than for others.

Sutherland and Hayne (2001) showed participants a video clip.

When asked misleading questions, their recall was more accurate for central details of the event than for peripheral.

Presumably the participants’ attention was focused on central features of the events and these memories were relatively resistant to misleading information.

This suggests that the original memories for central details survived and were not distorted, an outcome that is not predicted by the substitution explanation.

There is evidence that PED actually alters EWT, this is a limitation of memory conformity.

Skagerberg and Wright (2008) found that participants blended information together.

After seeing clips of mugger, some participants saw a mugger with dark brown hair and the others saw light brown, participants discussed the clips in pairs.

They often did not report what they had seen in the clips, nor what they heard from the co-witness, but a blend of the two.

EXAMPLE: medium brown hair instead of light or dark.

This suggests that the memory itself is distorted through contamination by misleading PED, rather than the result of memory conformity.

Other Factors

There are other factors that affect eyewitnesses testimony.

For example, familiarity of faces affects accuracy of identifying suspects.

Bruce and Young (1998)

Procedure: Psychology lecturers were caught on security cameras at the entrance of a building. Participants were asked to identify the faces seen on the security camera tape from photographs.

Results: The lecturers’ students made more correct identifications than other students and experienced police officers.

Conclusion: Previous familiarity helps when identifying faces. This is most obvious with ethnicity.

Unfamiliarity of faces may result in misleading information.

Another factor is stereotyping.

Cohen (1981) investigated the impact of stereotypes on memory.

Procedure: Participants were shown a video of a man and a woman eating in a restaurant. Half of the participants were told that the woman was a waitress. The other half were told she was a librarian. Later, all the participants were asked to describe the woman’s behaviour and personality.

Results: The two groups gave entirely different descriptions, which matched the stereotypes of a waitress or a librarian.

Conclusion: Stereotypes affect the accuracy of accounts of people.

Stereotypes may result in misleading information.

Anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion that brings feelings of tension, worry, and nervousness, this creates a physiological arousal, such as raised blood pressure. Stressful events such as witnessing a crime can trigger anxiety. This arousal has an impact on recall, this can affect the accuracy of EWT.

There are two main theories of how anxiety impacts recall.

Theory 1

Anxiety has a negative effect on recall

The physiological arousal in the body prevents us from paying attention to important cues negatively impacting recall. This is due to the weapon focus effect.

Weapon Focus: Attention of EW is drawn to a weapon therefore recall is reduced.

Tunnel Theory: Attention narrows to one aspect of the situation.

The eyewitness may fixate on the weapon due to fear, or the fight-or-flight response.

Due to this intense focus on the weapon, the person wielding the weapon is not really notice.

The EW does not take in their physical attributes

The EW does not take in other details of the event.

Thus, recall of the details is virtually non-existent.

Therefore, EWT is inaccurate

Johnson and Scott (1976)

Aim: to investigate impact of anxiety on EWT.

Procedure: Participants were led to believe they were going to take part in a lab study, but, while in the waiting room, the real study took place. Participants heard an argument proceeded by someone walking through - they either carried a pen (low anxiety group) or a blood-covered knife (high anxiety group).

Results: 49% of the low anxiety group accurately identified the man from a set of 50 photos. 33% of the high anxiety group accurately identified the man.

Theory 2

Anxiety has a positive effect on recall

The flight-or-fight response triggered by anxiety increases alertness and enhances memory. Anxiety triggers adrenaline, which results in a state of high alertness.

Yuille and Cutshall (1986)

Aim: to investigate impact of anxiety on EWT

Procedure: EWs of a real-life shooting in a gun shop in Vancouver were interviewed 4-5 months after the incident. 13/21 agreed to take part. The interview was compared to the original police interview. They were then asked to rate how stressed they were on a scale of 1-7.

Results: Participants who reported higher levels of stress accurately recalled more details of the event than those with lower reported stress levels. Approx. 88% compared to 75%. This suggests that anxiety has a positive impact on recall.

Yerkes and Dodson

The Yerkes-Dodson Law (1980)

The Yerkes-Dodson law represents the relationship between performance and arousal. This supports both theories as it shows the relation to both have a positive effect and negative effect. However, it may not be strictly showing the relationship between anxiety and recall.

Anxiety: Evaluation

Research Evidence

THEORY 1

Valentine and Mesout (2009)

Aim: to investigate impact of anxiety on recall

Procedure: Visitors to a horror labyrinth wore a heart monitor while in the labyrinth and then asked to fill in a self-report questionnaire about what they saw. One group had low anxiety, the other was high. The questionnaire asked about details of a specific actor they had seen.

Results: The low anxiety group accurately recalled more features of the actor than the high anxiety group. (75% accuracy compared to 17%) This supports the theory that anxiety has a negative effect on recall.

Strength: There is fairly high ecological validity and the results included objective quantitive data from the heart monitors. This objectively showed that one group experienced high levels of anxiety because of the high heart rates recored.

Weakness: It was a quasi-experiment meaning there was no control over variables, there was no random allocation.

THEORY 2

Parker et al (2006)

Aim: to investigate the impact of anxiety on recall

Procedure: People affected by a hurricane were interviewed to see if there was a relationship between the damage to their home and memory. This was how Parker et al operationalised anxiety.

Results: There was a found link between recall and the amount of damaged/anxiety. Moderate levels of anxiety was found to be associated with high accuracy of EWT. This supports the Yerkes-Dodson Law.

Strength: It has high ecological validity as the participants had experienced real anxiety is real-life. Unlike other studies, this one measured high, low, and moderate levels of anxiety.

Weakness: Anxiety was operationalised which may not reflect true experience. Someone who experience lots of damage may not be emotionally attached to the building therefore experiencing no anxiety. However, someone who has high levels of emotional attachment may experience high anxiety but very little damage overall.

Methods

Theory 1

Johnson and Scott

Strength: There is high internal validity because of the control over extraneous variables. This study shows medium levels of ecological validity.

Weakness: On the other hand, there are many ethical issues including deception, psychological harm and fully informed consent. The results may show the impact of other emotions on recall rather than anxiety - some participants may have found the man walking through surprising, shocking or confusing rather than making them anxious. Furthermore, if participants did not believe the argument then demand characteristics may have had an effect on their recall.

Theory 2

Yuille and Cutshall (1986)

Strength: High ecological validity as it was a real-life setting measuring experienced anxiety. Real witnesses participated so comparisons of accuracy over months could be tested in a valid way.

Weakness: Not all witnesses agreed to be interviewed, those who did not may have found the situation too traumatising to think about again or may have experience no anxiety. Ethical issues regarding psychological harm (re-living the death of a man) also limit the results.

Anxiety research might be testing surprise

Anxiety or Surprise

It has been argued that Johnson and Scott did not test anxiety, but instead tested surprise.

Participants were reacting to someone walking out with a pen or a knife, this does not necessarily illicit a fight-or-flight response commonly found with anxiety.

Participants may instead have been fearful of hearing a heated argument, or surprised to see someone walk out with a knife.

The lack of causality reduces the internal validity of the study.

Furthermore, in similar studies, it has been found that weapon focus may be due to surprise rather than anxiety.

In the Pickel (1998) study items such as scissors, handgun, wallet, and a raw chicken were used.

It was found that the more unusual the items were the worse recall was, suggesting an element of surprise and shock rather than anxiety.

Research into the effects of anxiety on the accuracy of EWT is limited as causality is difficult to establish – it is difficult to establish whether the participants actually felt anxious or were shocked and surprised.

Cognitive Interview

A cognitive interview (CI) is a strategy to improve the effectiveness of police interviews with EWs. It is an improvement of traditional police interview based on psychological research.

Report Everything: the interviewee is encouraged to report every detail of the event even if it seem irrelevant because it triggers other memories.

Reinstatement of Context: This allows the EW to have state/context dependent cues to improve recall.

Mental reinstatement of context could either be reinstating the environment or the physiological/mood of the witness mentally without leaving the interview room.

Physical reinstatement of context could either be reinstating the environment or the physiological/mood of the witness physically by taking them back to the scene or physically reinstating the state.

Changing the Order: The witness may be told or asked about details of the event in a different non-chronological order or in reverse to allow them to think deeper about the incident and trigger more memories. This can also be used to catch out suspects and undo their cover story.

Changing the Perspective: The witness may be asked to think about the details and recount them from someone else’s perspective to allow them to think deeper about the incident and trigger more memories. This removes a person’s schema reducing bias/prejudice thought.

The Enhanced Cognitive Interview was developed by Fisher et al (1987) with additional elements.

Minimising distractions

Reducing eyewitness anxiety

Getting the witness to speak slowly

Asking open-ended questions

Active listening

Further training about eye contact to interviewer

can mention ECI under cognitive interview, cannot be directly asked, not in the spec

Geiselman et al (1985)

Aim: to see if reinstating the context of an event will affect the accuracy of EWT.

Procedure: Participants were shown a police training video of a violent crime. After 2 days, half were interviewed with the context reinstated and the other half were simply interviewed.

Results: The half with the context reinstated were more accurate about the facts than those who were simply interviewed. This shows that reinstating the context does increase the accuracy of recall, supporting the need of CI.

Cognitive Interview: Evaluation

Köknken et al conducted a meta-analysis of ECI which showed it to be more effective then CI. However Köknken also found that more false positives were recalled - accurate recall increased by 81%, recall of false positive/misleading information increased by 61%. does false positives out weigh the usefulness of CI

Milne and Bull (2002) suggested that the most important features of CI were reporting everything and reinstating the context as they worked the best, especially together.

RWA: Police may be reluctant to complete CI or ECI completely and exactly because it is time-consuming, and can require additional training. Kebbell and Wagstaff (1996) found that most forces were only using “report everything” and “reinstate context.” Furthermore, CI is not set enough to ensure complete comparability (ability to be compared) as there are too many variables. It also may not be applicable to all police forces across the globe.