IER Notes 1 , 13-16

IER Notes

Chapter 1 : trade in the global economy

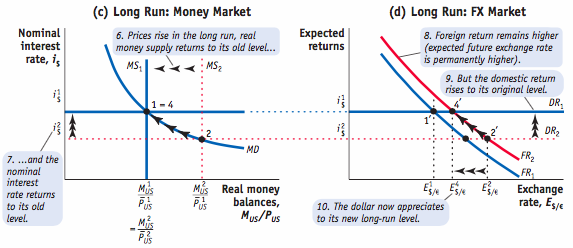

- international trade

Baiscs of world trade

Export : selling products from one country to another

Import : buying products from another country

- Trade Balance:the difference between the total value of its exports and imports. If a country exports more than it imports, it has a trade surplus, and if it imports more than it exports, it has a trade deficit.

- Bilateral Trade Balance: This refers to the trade balance between two specific countries. For example, the trade balance between the United States and China.

- Assumption of Balanced Trade: In economic models, it's assumed that each country has balanced trade, with exports equaling imports. This assumption simplifies analysis.

- Macroeconomic Factors: Trade deficits or surpluses are influenced by factors like overall spending and savings within an economy.

- Complexity of Trade: The value of products can involve components from multiple countries. For instance, even though an iPhone may be assembled in China, many of its parts are imported from other countries. This complexity challenges the accuracy of bilateral trade balances.

- Offshoring: Modern trade involves manufacturing processes spread across multiple countries, known as offshoring. This trend has increased due to reduced transportation and communication costs.

- World Trade Map: The map in Figure 1-2 illustrates the flow of exports and imports around the world in 2014, with trade in goods totaling about $19.8 trillion. Services are not included in the map due to measurement complexities.

- Trade in Goods vs. Services:

- Goods: These are physical products traded between countries. The map visualizes the flow of goods based on the width of the lines, with thicker lines representing larger trade volumes.

- Services: While not depicted in the map, services like tourism, financial services, and entertainment also contribute to international trade, though they are more challenging to measure.

- Regional Trade Highlights:

- Europe: Trade within Europe is substantial, accounting for almost one-quarter of world trade in 2014. The European Union (EU) fosters trade among its 28 member countries by imposing zero tariffs on imports from one another.

- Americas: Trade within the Americas, including North, Central, and South America, and the Caribbean, is significant, totaling about 9% of world trade.

- Asia: Asia accounts for about one-third of world trade, with China being a major exporter to the United States and other regions.

- Middle East and Russia: These regions, known for their oil reserves, also contribute significantly to global trade.

- Trade Barriers and Changes Over Time:

- Tariffs: Historical data show fluctuations in tariffs, with a notable increase during the interwar period due to policies like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. High tariffs can reduce trade and impose costs on economies.

- Global Financial Crisis: The financial crisis of 2008-2009 led to a slowdown in international trade, affecting many countries.

- Future of Trade:

- Free Trade Areas: Negotiations for free trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership aim to reduce tariffs and promote trade.

- Climate Change: Global warming may impact trade patterns, with the melting Arctic ice opening new shipping routes and opportunities for trade

1.2. Migration & foreging direct investement

Migration: the movement of people across borders,

foreign direct investment: the movement of capital across borders.

This part is on global migration patterns & the movement of people from low-wage to high-wage countries and the policies surrounding immigration in the European Union (EU) and the United States.

- Global Migration Trends:

- More than half (60%) of the 232 million foreign-born people worldwide come from countries outside the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- Asia has the highest number of migrants (68 million), followed by Africa (19 million) and Latin America (9 million).

- Restrictions on Immigration:

- Policy makers in OECD countries often implement restrictions on immigration, fearing that immigrants from low-wage countries will lower wages for local workers.

- Immigration policies are a hotly debated political issue in many countries, including Europe and the United States.

- Role of International Trade:

- International trade can act as a substitute for labor movement, raising living standards for workers in exporting industries.

- Increased openness to trade since World War II has provided opportunities for workers to benefit through trade, even when migration restrictions prevent them from directly earning higher incomes abroad.

- European Union Immigration Policies:

- Labor mobility was very open within the EU prior to 2004.

- Expansion of the EU to include central European countries led to concerns about labor migration from low-wage to high-wage countries.

- The Schengen Area allows for open borders between EU countries, except for the UK and Ireland.

- United States Immigration Policies:

- The United States has a significant population of Latin American immigrants, particularly from Mexico.

- Immigration policy is a frequent topic of debate, especially during presidential elections.

- Various attempts at immigration reform have been made, but comprehensive reform has not been achieved.

- 2016 US Presidential Election:

- During the 2016 election campaign, immigration was a prominent issue.

- Donald Trump proposed expelling all illegal Mexican immigrants and building a wall between the US and Mexico.

- Other Republican candidates also took strong stands against illegal immigration.

foreign direct investment (FDI) occurs when a firm in one country owns (in part or in whole) a company or property in another country.

- FDI can be described in one of two ways: as horizontal FDI or vertical FDI.

Horizental FDI

Horizontal FDI refers to the investment made by a company from one industrialized country into a company located in another industrialized country. This type of investment typically involves the acquisition of a company rather than the establishment of new facilities. The passage provides examples of horizontal FDI, such as the purchase of Tim Hortons by Burger King in 2014.

There are several reasons why companies engage in horizontal FDI:

- Tax Avoidance: One major reason is to minimize taxes. By moving headquarters to a country with lower corporate income tax rates or by strategically locating subsidiaries in countries with favorable tax policies, companies can reduce their tax burden.

- Market Access: Establishing a presence in another country provides improved access to that market. Local subsidiaries have better knowledge of the market and can facilitate marketing and distribution of products more effectively.

- Competitive Advantage: Horizontal FDI allows companies to leverage the strengths of both the acquiring and acquired firms. For example, combining expertise in different product lines or market segments can strengthen the competitiveness of the combined entity against competitors.

- Resource Sharing: Collaboration between production divisions of different firms allows for the sharing of technical expertise and resources, reducing duplication of efforts and costs. This can lead to greater efficiency and innovation.

Overall, horizontal FDI enables firms to expand their business operations across borders by acquiring existing companies in other industrialized countries.

Top of Form

Vertical FDI

Vertical FDI occurs when a company from an industrialized country owns a plant or facility in a developing country. Unlike horizontal FDI, which involves investment between industrialized countries, vertical FDI typically involves outsourcing production to take advantage of lower labor costs in developing countries.

The primary motivation behind vertical FDI is the pursuit of cost savings, particularly in labor expenses. Companies from industrialized economies seek to leverage their technological expertise and combine it with the cheaper labor available in developing countries. This allows them to produce goods more cost-effectively for the global market.

- China serves as a prominent example of vertical FDI, where many companies have established manufacturing facilities to capitalize on the country's abundant labor force and lower production costs. These firms often partner with local entities to navigate regulatory hurdles and gain access to the Chinese market.

In addition to cost savings, companies may also use vertical FDI to avoid tariffs and gain easier access to local markets. For instance, foreign automobile manufacturers have set up production plants in China, often in partnership with local companies, to circumvent high import tariffs and better serve the domestic market.

Despite China's reduction in tariffs following its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, foreign firms continue to maintain their manufacturing presence in the country. In fact, some are now exploring opportunities to export products manufactured in China to other markets.

Vertical FDI represents a strategy employed by multinational corporations to optimize their production processes, lower costs, and enhance their competitiveness in the global marketplace.

Largest stocks of FDI are in Europe ,

CCL

Globalization encompasses many aspects, like the flow of goods, services, people, and firms across borders, as well as the spread of culture and ideas globally. While it may seem like a modern phenomenon, globalization has historical roots, with strong international trade and financial integration existing before World War I. However, global linkages were disrupted by the war and the Great Depression. Since World War II, there has been a rapid resurgence of global trade, outpacing the growth in world GDP, facilitated by international institutions like the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and others established to promote freer trade and economic development.

Migration across countries, unlike international trade, faces restrictions due to concerns about its impact on wages. However, these fears may not always be justified, as immigrants can often be assimilated into host countries without adversely affecting wages. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), on the other hand, is relatively unrestricted in industrialized countries but may face limitations in developing countries. Firms invest in different countries to capitalize on factors like lower wages and to spread their business operations and production knowledge across borders. Migration and FDI are integral components of contemporary globalization.

Key points to consider:

- The trade balance of a country depends on macroeconomic conditions and is determined by the difference between its exports and imports.

- The nature of traded goods has evolved from raw materials and basic processed goods to highly processed consumer and capital goods, with goods often crossing borders multiple times during manufacturing.

- A significant portion of international trade occurs between industrialized countries, with Europe and the United States accounting for a substantial share.

- Trade models often emphasize differences between countries, but trade between similar countries also occurs, involving the exchange of different varieties of goods.

- Larger countries tend to have smaller trade-to-GDP ratios due to significant internal trade. However, smaller economies like Hong Kong and Singapore have high trade-to-GDP ratios.

- Most world migration originates from developing countries, with migrants often seeking entry into wealthier, industrialized countries.

- International trade serves as a substitute for migration, allowing workers to improve their standard of living by working in export industries, even if they cannot migrate.

- The majority of world FDI occurs between industrialized countries, with Europe and the United States being significant participants. The OECD countries account for a substantial share of global FDI flows.

The debate over whether the European Central Bank (ECB) should raise interest rates to counter inflation is a complex one, with arguments on both sides.

Arguments for Raising Interest Rates:

- Taming Inflation: Higher interest rates can be used as a tool to curb inflation by reducing the amount of money circulating in the economy. When interest rates rise, borrowing becomes more expensive, leading to reduced spending and investment, which can help slow down inflationary pressures.

- Maintaining Price Stability: Central banks like the ECB have a mandate to maintain price stability, which often means keeping inflation within a target range. Raising interest rates can be seen as a proactive measure to ensure that inflation doesn't spiral out of control, which could have detrimental effects on consumers' purchasing power and overall economic stability.

- Preserving Credibility: Central banks' credibility is closely tied to their ability to control inflation. If inflation persists above target levels for too long without a response from the central bank, it could undermine public confidence in the bank's ability to fulfill its mandate, potentially leading to higher inflation expectations and further exacerbating the problem.

Arguments against Raising Interest Rates:

- Risk to Economic Recovery: Raising interest rates could potentially slow down economic growth, particularly if it's done too quickly or aggressively. Higher borrowing costs can discourage investment and consumption, which are crucial drivers of economic activity. In an environment where many European countries are still recovering from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, overly restrictive monetary policy could derail progress.

- Debt Servicing Costs: Higher interest rates would increase the cost of servicing government and private sector debt. European countries, particularly those with high levels of public debt, could face significant challenges in managing their debt burdens if interest rates rise, potentially leading to fiscal strains and even sovereign debt crises in extreme cases.

- Exchange Rate Implications: Raising interest rates could lead to an appreciation of the euro against other currencies, which could negatively impact European exporters by making their goods more expensive in foreign markets. This could further dampen economic activity and exacerbate any slowdown resulting from higher interest rates.

In conclusion, the decision to raise interest rates to counter inflation involves weighing the immediate need to control price pressures against the potential risks to economic growth, debt sustainability, and exchange rate dynamics. The ECB must carefully assess the current economic conditions and inflation outlook to determine the appropriate course of action that balances these competing concerns.

COVID-19 Pandemic:

During the COVID-19 pandemic, central banks around the world, including the ECB, implemented aggressive monetary policy measures to support economies reeling from lockdowns and disruptions. Interest rates were slashed to historically low levels to stimulate borrowing and spending and to prevent a deeper economic downturn.

Impact on Popular Companies:

- Airline Industry: Companies like Lufthansa, British Airways, and Air France-KLM faced significant challenges due to travel restrictions and reduced demand for air travel. Low interest rates helped these companies access cheaper financing to weather the crisis, but the sector's recovery was heavily dependent on factors like vaccine distribution and easing travel restrictions.

- Hospitality and Tourism: Hotel chains like Marriott International and Hilton Worldwide experienced a sharp decline in bookings as travel ground to a halt. Low interest rates provided some relief by reducing borrowing costs for expansion or renovation projects, but the industry's recovery was slow and uneven as consumer confidence remained subdued.

- Retail Sector: Retail giants like H&M, Inditex (owner of Zara), and Macy's faced store closures and reduced foot traffic during lockdowns. Low interest rates supported consumer spending by reducing the cost of credit card debt and mortgages, but brick-and-mortar retailers struggled to adapt to changing consumer preferences and the rise of e-commerce.

Great Recession:

During the Great Recession of 2008-2009, central banks responded to the financial crisis by lowering interest rates and implementing unconventional monetary policy measures like quantitative easing to stabilize financial markets and stimulate economic growth.

Impact on Popular Companies:

- Automotive Industry: Companies like General Motors and Ford faced a sharp decline in demand for cars and trucks as consumer spending contracted and credit markets froze. Low interest rates helped support auto sales by reducing the cost of financing for car loans, but the industry faced restructuring and consolidation as weaker players struggled to survive.

- Financial Institutions: Banks like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns collapsed during the financial crisis due to exposure to toxic assets and liquidity problems. Low interest rates and government interventions like bailouts and liquidity injections helped stabilize the financial system and restore confidence, but regulatory reforms were implemented to prevent future crises.

- Technology Sector: Companies like Apple and Google weathered the Great Recession better than many traditional industries due to their strong balance sheets and innovative products. Low interest rates and government stimulus measures indirectly supported tech spending by boosting consumer and business confidence, but the sector still faced challenges like reduced corporate IT budgets and weaker demand for high-end gadgets.

In both the COVID-19 pandemic and the Great Recession, low interest rates played a critical role in supporting economic recovery and mitigating the impact of the crises on popular companies. However, the debate around raising interest rates to counter inflation remains relevant as economies gradually recover and central banks seek to prevent overheating and financial imbalances.

Bottom of FormChapter 12 : the global macroeconomy

1. Why do exchange rates matter and what explains their behavior?

2. Why do countries borrow from and lend to eachother and with what effects?

3. How do government policy choices affect macroeconomic outcomes?

12.1 Foreign exchange : currencies & crises

Exchange rates : the value of one currency in terms of another currency. They determine the price at which one currency can be exchanged for another in the foreign exchange market.

- Exchange rates are crucial for international trade and investment because they influence the cost of goods and services between countries, as well as the profitability of cross-border transactions.

The main purpose of exchange rates is to facilitate international trade and investment by providing a way to convert one currency into another. They help businesses and individuals assess the relative value of different currencies and make decisions about imports, exports, and investments. Exchange rates also influence a country's economic stability, impacting its balance of trade, inflation rate, and overall competitiveness. Governments and central banks often intervene in currency markets to manage exchange rates and achieve economic goals, such as controlling inflation or promoting exports.

How Exchange rates behave

Exchange rates behave differently depending on the monetary policies of the countries involved.

Either they’re Fixed/ pegged or Stable Exchange Rates, like the Chinese yuan in relation to the US dollar, have relatively stable exchange rates, which are often fixed or pegged to another currency.

- This means their value remains consistent over time, with minor fluctuations controlled by the government. In a fixed exchange rate system, the government or central bank sets the value of the currency relative to another currency, maintaining stability but limiting flexibility

Currencies can also be Floating or Flexible Exchange Rates like the euro in relation to the US dollar have floating exchange rates, which fluctuate more widely based on market forces like supply and demand.

In contrast, a floating exchange rate system allows the currency's value to be determined by market forces, resulting in more frequent and larger fluctuations in the exchange rate.

Several market factors contribute to the flexibility of exchange rates:

- Supply and Demand for Currencies: Like any other market, the foreign exchange market operates based on the forces of supply and demand. If there's high demand for a particular currency, its value relative to other currencies will increase, and vice versa. Factors affecting demand include trade balances, investment flows, and geopolitical events.

- Interest Rates: Central banks' monetary policy decisions, particularly regarding interest rates, play a crucial role in exchange rate movements. Higher interest rates attract foreign investment, leading to increased demand for a currency and thus appreciation. Conversely, lower interest rates may lead to depreciation as investors seek higher returns elsewhere.

- Inflation Rates: Countries with lower inflation rates generally see an appreciation of their currency because their purchasing power increases. Conversely, higher inflation rates can lead to currency depreciation as the cost of goods and services rises relative to other currencies.

- Economic Performance: Exchange rates are influenced by a country's economic performance indicators such as GDP growth, unemployment rates, and industrial production. Strong economic performance attracts foreign investment, driving up demand for the currency and its value.

- Political Stability and Economic Policies: Countries with stable political environments and sound economic policies tend to have more stable currencies. Political instability, corruption, or unpredictable economic policies can lead to currency depreciation as investors lose confidence in the currency's value.

- Speculation: Traders and investors in the foreign exchange market engage in speculative activities based on their expectations of future exchange rate movements. Speculation can lead to short-term fluctuations in exchange rates, especially in response to news events or market sentiment.

Why exchange rates matter

Exchange rates matter for several reasons:

- Impact on International Trade: Changes in exchange rates affect the relative prices of goods and services between countries. When a currency appreciates (increases in value), exports become more expensive for foreign buyers, potentially reducing demand for those goods and leading to a decline in exports. Conversely, a depreciating currency makes exports cheaper and can stimulate foreign demand. This can have significant implications for businesses that rely on international trade, as illustrated by the Swiss cheesemaker's dilemma in the example.

- Effect on Asset Prices: Exchange rate fluctuations also influence the relative value of assets held in different currencies. For example, when the value of a currency falls, the value of assets denominated in that currency decreases when converted into another currency. This can lead to capital gains or losses for investors holding foreign assets, impacting their wealth and investment decisionS.

- International Investment: Exchange rate movements affect the attractiveness of investing in foreign markets. A stronger domestic currency makes foreign investments cheaper for domestic investors, while a weaker currency makes domestic assets more attractive to foreign investors. This can influence capital flows across borders and impact investment decisions made by firms, governments, and individuals.

- Economic Stability: Exchange rate stability is crucial for maintaining economic stability and confidence in the financial system. Sharp fluctuations in exchange rates can disrupt trade, investment, and financial markets, leading to uncertainty and volatility. Central banks often intervene in currency markets to stabilize exchange rates and support economic stability.

- International Trade: They determine the prices of goods sold between countries. When a currency goes up, exports become more expensive, and when it goes down, exports become cheaper.

- Asset Prices: Changes in exchange rates can affect the value of investments held in different currencies. This can lead to gains or losses for investors.

- International Investment: Exchange rates influence the attractiveness of investing in foreign markets. A strong domestic currency makes foreign investments cheaper, while a weak currency makes domestic assets more appealing.

- Economic Stability: Stable exchange rates are important for keeping the economy steady. Big changes can cause uncertainty and disrupt trade and investments. Central banks sometimes step in to keep exchange rates stable.

When exchanges misbehave

Exchange rate crises occur when a currency suddenly loses value against another currency after a period of stability. These crises can lead to severe economic and social consequences, as seen in Argentina's crisis in 2001-2002. During this time, the Argentine peso, which had been fixed to the U.S. dollar, lost value rapidly, leading to financial chaos, debt default, high inflation, unemployment, and widespread poverty.

Argentina's experience is not unique, as exchange rate crises have occurred in many countries. From 1997 to 2015, there were 32 such crises, often resulting in significant economic downturns and political instability. Countries affected include those in East Asia, as well as Liberia, Russia, Brazil, Iceland, and Ukraine.

During exchange rate crises, output decreases, banking and debt problems emerge, and political turmoil often follows. Governments may seek external help from organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the World Bank to address the crisis. These events highlight the importance of understanding and addressing exchange rate dynamics, especially during times of crisis.

Top of Form

12.2 Globalization of finance : debts & deficits

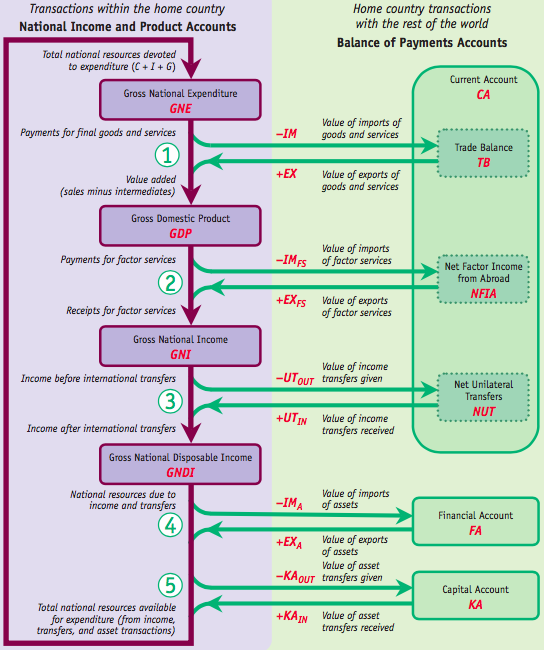

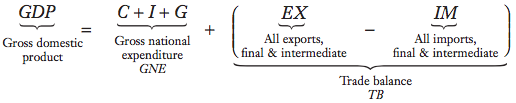

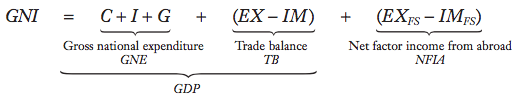

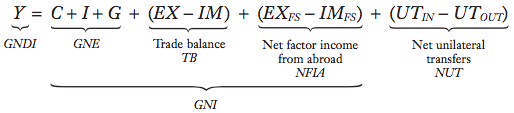

Deficits & surplus : the balance of payments

The balance of payments : to the tracking of a country's economic transactions with the rest of the world.

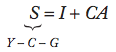

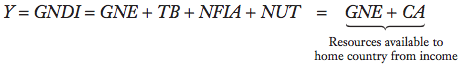

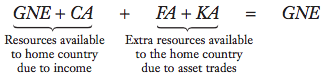

The balance of payments, much like personal finances, involves tracking income and expenditure. If income exceeds expenditure, there's a surplus, but if expenditure surpasses income, there's a deficit. This difference between income & expenditure is known as the current account, indicates whether a country is living within its means.

- If a country's income exceeds its expenditure, it has a current account surplus, indicating that it is exporting more than it imports and is a net lender to the rest of the world. Conversely, if expenditure exceeds income, the country has a current account deficit, suggesting that it is borrowing from the rest of the world to finance its excess spending.

For instance, in the United States, expenditure has often exceeded income since 1990, resulting in a current account deficit, except for a small surplus in 1991. To cover this deficit, the U.S. borrows from the rest of the world through financial transactions, similar to how households might manage deficits by borrowing money.

Since the world economy operates as a closed system, with no external borrowing sources, if one country like the U.S. runs a deficit, others must run surpluses. Thus, while individual countries may have deficits or surpluses, globally, the finances balance out.

Understanding the balance of payments is crucial for assessing a country's economic health and its position in the global economy. It reflects whether a country is living within its means or relying on external borrowing to sustain its economic activities.

Debtors & creditors : External wealthBottom of Form

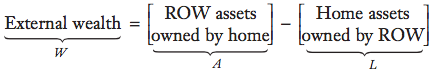

Wealth/net worth : Assets ( what others owe you) – liabilities (what u owe).

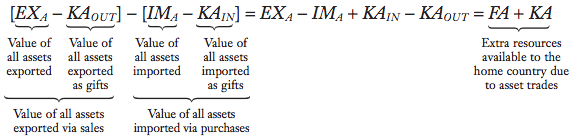

External wealth is a country's net worth and it’s the difference between its foreign assets (what it is owed by the rest of the world) and its foreign liabilities (what it owes to the rest of the world).

- Creditor Nation: When a country's external wealth is positive, it means that other nations owe it money. In other words, it's a creditor nation.

- Debtor Nation: Conversely, if a country's external wealth is negative, it indicates that it owes money to other nations, making it a debtor nation.

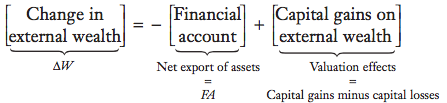

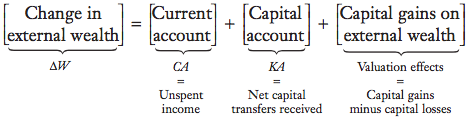

Changes in a nation's external wealth are influenced by its current account balance. A surplus leads to an increase in external wealth, while a deficit causes it to decline.

Ex: persistent current account deficits in the United States since the 1980s have contributed to a significant decrease in its external wealth, making it the world's largest debtor by the second quarter of 2015. Similarly, Argentina's external wealth declined due to its recurring current account deficits in the 1990s.

However, external wealth isn't solely determined by income and expenditure. Factors like capital gains or losses on investments, as well as deliberate actions such as debt defaults, also play a role. For example, Argentina's external wealth increased in 2002 despite defaulting on its government debt, as it simultaneously reduced its liabilities. Therefore, fluctuations in external wealth can occur not only due to economic imbalances but also due to market dynamics and policy decisions.

Darling & deadbeats : defaults and other risks

Defaults on government debt are not uncommon in international finance. Since 1980, several countries have defaulted on private creditors multiple times, including Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Greece, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and others. Additionally, countries that fail to make payments on loans from international financial institutions, like the World Bank, could also be considered in default, although such cases may be managed to avoid formal default.

Sovereign governments typically have the power to default on their debt without facing legal consequences. They can also impact creditors through various means, such as seizing assets or changing laws and regulations after investments have been made.

To mitigate these risks, international investors carefully assess and monitor debtors. Nations and firms are assigned credit ratings based on their financial behavior. A high credit rating indicates low risk and provides access to low-interest loans, while a low rating means higher interest rates and limited credit.

Countries issuing bonds to raise funds are also rated by agencies like Standard & Poor's (S&P). Bonds rated BBB- or higher are considered investment-grade, while those rated BB+ and lower are classified as junk bonds. Poorer ratings are associated with higher interest rates, with the difference between rates on safe U.S. Treasury bonds and bonds from riskier countries termed as country risk. For instance, on January 8, 2016, Poland and Mexico had relatively low country risk, while Brazil and Turkey faced higher penalties due to their lower credit ratings.

12.3. Gov & institutions : Policies & performance

Integration & Capital Controls : The regulation of International Finance

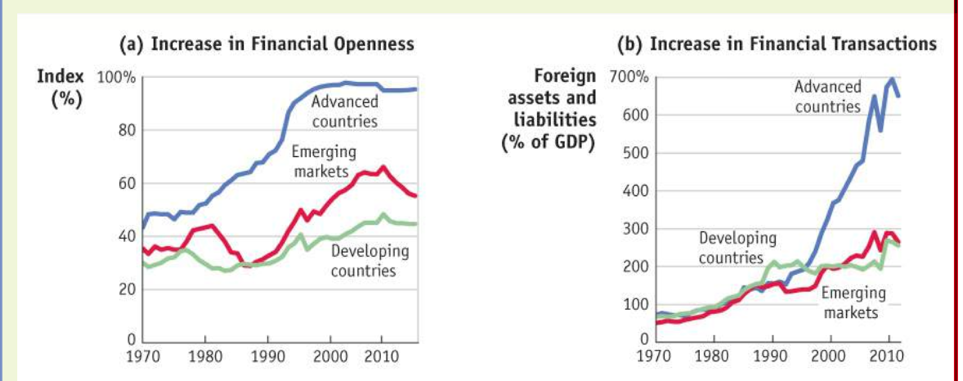

The trend towards financial globalization since 1970 is evident in Figure 12-5. Panel (a) displays an index of financial openness, which means it shows how open countries are to financial transactions. It's like a scale: 0% means countries have tight controls, while 100% means they're fully open. The graph divides countries into three groups: advanced, emerging, and developing.

The trend towards financial globalization since 1970 is evident in Figure 12-5. Panel (a) displays an index of financial openness, which means it shows how open countries are to financial transactions. It's like a scale: 0% means countries have tight controls, while 100% means they're fully open. The graph divides countries into three groups: advanced, emerging, and developing.

Advanced countries, characterized by high levels of income per person and strong integration into the global economy, led the shift towards financial openness. In the 1980s, many of these countries abolished capital controls that had been in place since World War II. Emerging markets, middle-income countries experiencing growth and greater integration, also began opening up financially in the 1990s, albeit to a lesser extent. Developing countries, with lower income levels and less integration, followed suit, albeit slowly.

Panel (b) illustrates the consequence of these policy changes: a significant increase in cross-border financial transactions. Total foreign assets and liabilities, expressed as a fraction of output, surged by a factor of 10 or more as the world became more financially open. This trend was most pronounced in advanced countries but also evident in emerging markets and developing countries.

As an example of evading control, Zimbabwe implemented capital controls, requiring U.S. dollars to be traded for Zimbabwe dollars only through official channels at an official rate. However, unofficial street markets emerged, reflecting a different reality.

- Financial Openness: This refers to the degree to which a country's financial system allows for cross-border financial transactions, such as investment flows and capital movements. A fully financially open economy would have no restrictions on such transactions, while a closed economy would tightly control them.

- Capital Controls: These are rules set by governments to manage the flow of money entering and leaving their economies. Capital controls can take different forms, like limits on currency exchange, restrictions on foreign investments, or taxes on money moving across borders.

- Credit Ratings: These are evaluations of how likely a borrower, like a government or a company, is to repay its debts. Credit rating agencies provide these assessments to help investors gauge the risk of investing in the borrower's debt. Higher ratings mean lower risk, while lower ratings indicate higher risk.

- Country Risk: This is the extra risk investors face when investing in assets or securities from a specific country, compared to investing in something considered risk-free, like U.S. Treasury bonds. Country risk factors in things like political stability, economic performance, and the likelihood of a government defaulting on its debts. Higher country risk usually leads to higher interest rates for bonds issued by that country.

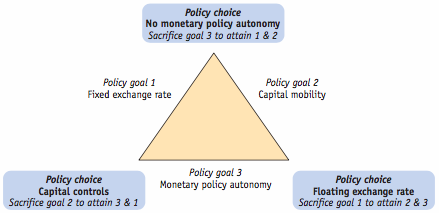

Independence & monetary policy : the choice of exchange rates regimes

Exchange rate regimes basically refer to how a country manages its currency in relation to other currencies. There are two main types: fixed and floating.

- Fixed regimes : involve setting a specific value for the exchange rate,

- floating regimes : allow the rate to be determined by market forces. Both types are common globally.

- Fixed Regimes: Under this system, a country sets a specific value for its currency against another currency or a basket of currencies. This value is usually maintained by the country's central bank through buying or selling its currency in the foreign exchange market. Many countries use fixed regimes to provide stability to their currency's value.

- Floating Regimes: In contrast, floating regimes allow a country's currency value to be determined by market forces like supply and demand. The exchange rate fluctuates freely based on factors like interest rates, economic indicators, and investor sentiment. This system gives countries more flexibility but can lead to volatile currency movements.

The choice of which regime to adopt is a big decision for policymakers and can have significant impacts on the economy. Some argue that fixed regimes offer stability but limit a country's ability to respond to economic changes, while floating regimes provide flexibility but can result in unpredictable currency values.

Despite the existence of many currencies globally, some regions have moved towards currency integration, like the Eurozone, where multiple countries share a common currency (the euro) and monetary policy responsibilities. Others have opted for using foreign currencies, relinquishing control over their monetary policy.

Governance

Institutions, often referred to as governance, encompass a range of factors such as legal, political, social, and cultural structures within a society. These elements play a crucial role in shaping a nation's economic prosperity and stability.

- Institutional Quality: It's measured using indicators like voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. Better-quality institutions are associated with higher levels of income per capita and lower income volatility.

- Exchange Rate Regimes: These are frameworks that dictate how a country manages its currency in relation to others. The two main types are fixed regimes, where the value is set against another currency, and floating regimes, where the value is determined by market forces.

- The Spence Report: This landmark report led by Michael Spence focuses on strategies for sustained growth and inclusive development. It highlights a shift away from universal policy prescriptions towards pragmatic, context-specific approaches. It emphasizes the importance of diagnosing specific economic bottlenecks and experimenting with targeted policy initiatives.

- Factors Influencing Institutional Variation: These include historical legacies like colonization, legal systems, and resource endowments. For example, regions settled by Europeans often developed better institutions compared to those without European influence.

Chapter 13 : Introduction to exchange rates & the foreign exchange market

13.1 exchange rate essentials

Exchange Rate: the price of one currency in terms of another currency. It tells you how much of one currency you need to buy a unit of another currency.

- Quoting Exchange Rates: Exchange rates can be quoted in two ways:

- Home Currency Units per Foreign Currency: This tells you how many units of your home currency you need to buy one unit of foreign currency.

- Foreign Currency Units per Home Currency: This tells you how many units of foreign currency you can buy with one unit of your home currency.

Example: If the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the euro is $1.15 per euro, it means you need $1.15 to buy one euro. Alternatively, you can express it as €0.87 per U.S. dollar, indicating you can buy €0.87 with one U.S. dollar.

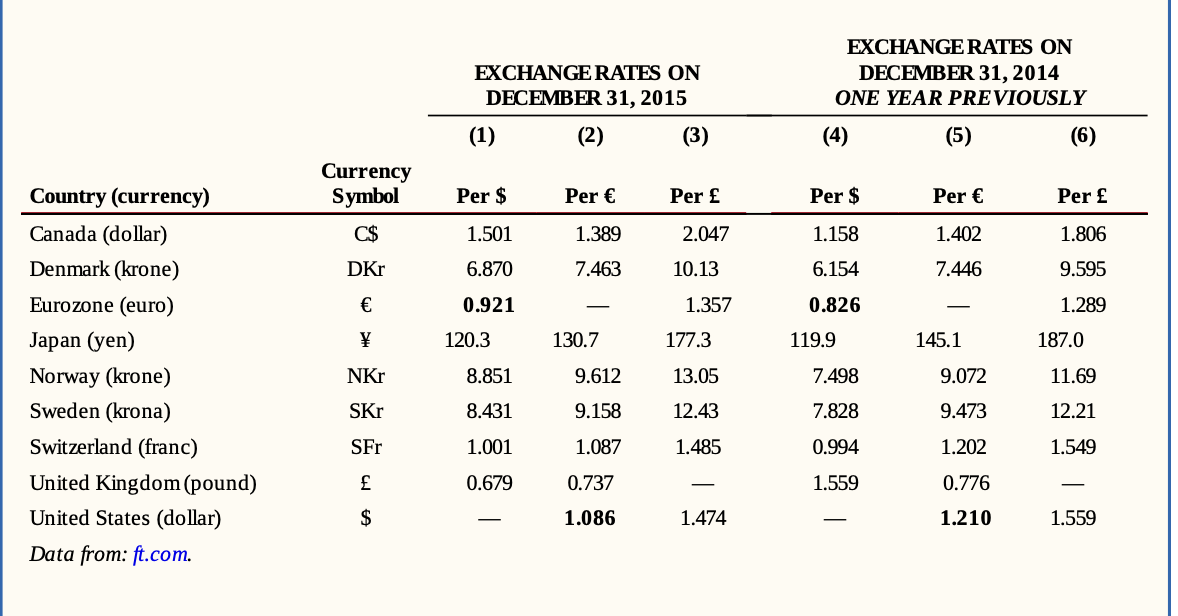

Defining the exchange rates

When we talk about exchange rates, we're discussing the value of one currency compared to another. Typically, we express/ quote this as units of our home currency per unit of the foreign currency.

EX: if you're in the U.S., you might see the price of euros quoted as $1.15 per euro. But if you're in the Eurozone, you'd see it as €0.87 per U.S. dollar.

To keep things clear, we'll stick to one way of quoting exchange rates throughout this book: units of the home currency per unit of the foreign currency.

EX: if we're talking about the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the euro, we'll write it as E$/€ = 1.086, meaning $1.086 per euro from the U.S. perspective. Conversely, from the Eurozone perspective, it would be E€/$ = 0.921, indicating €0.921 per U.S. dollar.

Remember, the value of one currency in terms of another always equals the reciprocal of the value of the second currency in terms of the first. So, E$/€ = 1/E€/$. In our example, 1.086 = 1/0.921.

Remember, the value of one currency in terms of another always equals the reciprocal of the value of the second currency in terms of the first. So, E$/€ = 1/E€/$. In our example, 1.086 = 1/0.921.

Appreciations & Deprecoations

When we talk about exchange rates changing over time, we often use terms like appreciation and depreciation.

Appreciation : means that a currency has gained value compared to another currency

Depreciation : means it has lost value.

- Let's say the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the euro changes. If the exchange rate rises, it means more dollars are needed to buy one euro. This is called depreciation of the dollar because it's getting weaker compared to the euro. Conversely, if the exchange rate falls, fewer dollars are needed to buy one euro, indicating appreciation of the dollar against the euro.

The same applies from the Eurozone perspective. If the Eurozone exchange rate rises, it means more euros are needed to buy one dollar, indicating depreciation of the euro. If it falls, fewer euros are needed to buy one dollar, indicating appreciation of the euro against the dollar.

Interestingly, changes in exchange rates are always opposite for the two currencies involved. For example, if the dollar appreciates against the euro, it means the euro must depreciate against the dollar. This is because the two exchange rates are reciprocal of each other.

To measure how much a currency has appreciated or depreciated, we calculate the percentage change in its value relative to the other currency.

To calculate the percentage change:

- Find the difference between the new and old exchange rates.

- Divide the difference by the old exchange rate.

- Multiply by 100 to get the percentage change.

Example:

- Suppose the exchange rate for the U.S. dollar against the euro was $1.210 last year and $1.086 this year.

- The change is $1.086 - $1.210 = -$0.124.

- To find the percentage change: (-$0.124 / $1.210) * 100 = -10.25%.

- So, the euro depreciated against the dollar by 10.25%.

- Similarly, if the euro value of the dollar was €0.826 last year and €0.921 this year:

- The change is €0.921 - €0.826 = +€0.095.

- The percentage change is (+€0.095 / €0.826) * 100 = +11.50%.

- Therefore, the dollar appreciated against the euro by 11.50%.

- Note that the size of one country’s appreciation (here 11.50%) does not exactly equal the size of the other country’s depreciation (here 10.25%). For small changes, however, the opposing movements are approximately equal.

Multilatéral exchange rates

Multilateral exchange : Measure changes in a currency's value against many currencies.

- Accounts for trade weights to calculate an average of bilateral changes.

Calculation: To calculate the change in the effective exchange rate, economists use trade weights to aggregate bilateral exchange rate changes.

- Multiply each exchange rate change by its corresponding trade share.

- Add up the weighted changes to find the effective exchange rate change.

EX: If a country's currency appreciates 10% against 1 and depreciates 30% against 2, suppose 40% of Home trade is with country 1 and 60% is with country 2

- Multiply each change by the trade share and then add them up

- (−10% · 40%) + (30% · 60%) = (−0.1 · 0.4) + (0.3 · 0.6) = −0.04 + 0.18 = 0.14 = +14%.

Significance: Multilateral exchange rates provide a broader view of a currency's performance in the global market, considering its value relative to multiple currencies rather than just one.

Figure 13-1: The figure shows the change in the value of the U.S. dollar measured against two different baskets of foreign currencies. It illustrates how the dollar's value can vary depending on the currencies included in the basket and their respective trade relationships with the U.S.

Example: Using Exchange Rates to Compare Prices in a Common Currency

Top of Form

In this example, James Bond needs to compare tuxedo prices in different cities, each priced in its local currency: £2,000 in London, HK$30,000 in Hong Kong, and $4,000 in New York. To make a fair comparison, he converts all prices to a common currency using exchange rates.

- In Scenario 1, the Hong Kong tuxedo costs HK$30,000, divided by the exchange rate of HK$15 per £, equals £2,000. Similarly, the New York tuxedo priced at $4,000, divided by the exchange rate of $2 per £, also equals £2,000. Thus, both tuxedos are priced equally in British currency.

- In Scenario 2, with changes in exchange rates, the Hong Kong tuxedo becomes cheaper at £1,875 (£30,000 divided by 16), while the New York tuxedo becomes more expensive at £2,105 ($4,000 divided by 1.9)

- In Scenario 3, with further changes, the Hong Kong tuxedo becomes more expensive at £2,143 (£30,000 divided by 14), while the New York tuxedo becomes cheaper at £1,905 ($4,000 divided by 2.1).

- In Scenario 4, the pound depreciates against both currencies, resulting in a lower price of £2,000 for the London tuxedo, while the tuxedos in other cities become more expensive.

This example illustrates how changes in exchange rates affect the prices of goods when expressed in a common currency.

Bottom of Form

In summary:

- Changes in exchange rates affect prices of foreign goods in the home currency.

- Exchange rate fluctuations impact the relative prices of goods between home and foreign countries.

- A depreciation of the home country's exchange rate makes its exports cheaper for foreigners and imports more expensive for residents.

- Conversely, an appreciation of the home country's exchange rate makes its exports more expensive for foreigners and imports cheaper for residents.

13.2 exchange rates in practice

Exchange rate regimes : fixed vs floating

Economists group different patterns of exchange rate behavior into categories known as exchange rate regimes.

- Fixed (or pegged) exchange rate regimes:

- Exchange rate remains stable or fluctuates within a narrow range against a base currency.

- Government intervention often required to maintain the fixed rate.

- Examples include countries pegged to the US dollar or the euro.

- Floating (or flexible) exchange rate regimes:

- Exchange rate fluctuates freely in a wider range without government intervention.

- Appreciations and depreciations occur regularly.

- Examples include many major currencies like the US dollar, euro, and Japanese yen.

Exchange Rate Behavior:

- Advanced Countries (Figure 13-2):

- Illustrates exchange rates against the U.S. dollar and the euro from 1996 to 2015.

- Currencies like the yen, pound, and Canadian dollar float against the U.S. dollar.

- Pound and yen also float against the euro.

- The Danish krone maintains a fixed exchange rate against the euro, with minimal variation.

- Developing Countries (Figure 13-3):

- Depicts exchange rate behavior in emerging markets and developing nations.

- Examples include India, Thailand, South Korea, and Latin American countries.

- Varied experiences, including managed float, exchange rate crises, fixed rates with bands, and dollarization in Ecuador.

Currency Unions and Dollarization:

- Currency union: Formed by multiple economies adopting a common currency, with a central monetary authority.

- Dollarization: Occurs when a country adopts the currency of another nation.

- Reasons for dollarization range from economic size to monetary management and policy considerations.

Exchange Rate Regimes of the World (Figure 13-4):

- Provides a classification of exchange rate regimes globally, from fixed to floating.

- Includes categories such as currency unions, ultra-hard pegs, crawling bands, and freely floating regimes.

- Data covers 182 economies and highlights the prevalence of different regime types.

Looking Ahead:

- The book's analysis focuses on understanding the mechanisms of fixed and floating rate regimes.

- Examines patterns of regime choices across countries and explores the underlying reasons for these choices.

13.3 The Market for Foreign Exchange

The foreign exchange market, or forex market : is where currencies are bought and sold. It's like a big marketplace where people, companies, and institutions trade currencies with each other. Unlike a physical market, forex trading happens electronically and globally.

Key points about the forex market:

- Market Size: The forex market is vast and has grown significantly in recent years. In April 2013, it traded $5.3 trillion per day in currency, with substantial increases compared to previous years.

- Major Centers: The four major foreign exchange centers are the United Kingdom, the United States, Singapore, and Japan. These centers account for over 70% of the global forex trade, with London being the largest hub.

- Global Coverage: Due to time-zone differences, forex trading occurs continuously across the globe. Smaller trading centers like Hong Kong, Sydney, Paris, and Zurich also contribute to market activity.

The spot contract

A spot contract in the forex market is an agreement between two parties to exchange currencies immediately. It's called "spot" because the transaction happens right away. The exchange rate for this transaction is called the spot exchange rate. With advancements in technology, spot trades are almost risk-free because settlements occur in real-time, minimizing the risk of default. While retail transactions are typically small, most forex trading involves commercial banks in major financial centers, and spot contracts make up the majority of these transactions, accounting for over 80%.

Transaction costs

Transaction costs in the forex market refer to the fees and commissions paid by individuals or firms when buying or selling foreign currency. When individuals buy currency through retail channels, they often pay higher prices and receive lower prices when selling, resulting in a spread between the buying and selling prices. This spread can range from 2% to 5% for retail transactions but is much smaller for large transactions by big firms or banks, typically less than 0.10% (10 basis points). Market frictions like spreads create a gap between the buying and selling prices, known as transaction costs. While these costs are significant for retail investors, they are often negligible for large investors due to low-cost trading, especially for actively traded major currencies. As a result, macroeconomic analysis typically disregards transaction costs for key investors in the forex market.

Derivatives

Derivatives are contracts in the forex market that are related to the spot contract, which is an immediate exchange of currencies. These contracts include forwards, swaps, futures, and options. They derive their value and pricing from the spot rate. While the spot contract is the most common, derivatives also play a significant role. Forwards are agreements to exchange currencies at a future date at a set rate, while swaps combine spot and forward contracts. Derivatives represent a smaller portion of trades compared to spot contracts. Spot and forward rates usually move together closely, as shown in Figure 13-5, which illustrates trends in the dollar-euro market. However, delving into the complexities of derivatives involves understanding associated risks, which is beyond the scope of this chapter.

In the forex market, there are several derivative contracts commonly used for trading currencies at different times or under different conditions:

- Forwards: These contracts involve agreeing today to exchange currencies at a future date, with the price fixed in advance. They help manage risk because the exchange rate is predetermined.

- Swaps: Swaps combine a spot sale of one currency with a forward repurchase of the same currency. They are useful for parties frequently dealing in the same currency pair, reducing transaction costs.

- Futures: Futures contracts also involve agreeing to exchange currencies in the future, but they are standardized, trade on organized exchanges, and mature at regular dates.

- Options: Options give the buyer the right (but not the obligation) to buy or sell a currency at a predetermined exchange rate in the future. This provides flexibility and can be used for hedging or speculation.

These derivative products serve different purposes:

- Hedging: For example, a firm receiving payment in a foreign currency may use options to protect against unfavorable exchange rate movements, ensuring a minimum acceptable rate.

- Speculation: Traders may use futures contracts or options to bet on future exchange rate movements, aiming to profit from anticipated changes in currency values.

For instance:

- Hedging Example: A U.S. firm expecting €1 million in 90 days may buy call options on dollars to protect against a weakening euro, ensuring a minimum acceptable exchange rate.

- Speculation Example: If a trader believes the euro will strengthen in the next year, they might buy euro futures contracts, aiming to profit if the actual exchange rate exceeds the contract rate. However, if the euro weakens, they may incur a loss.

These examples demonstrate how derivatives can be used for both risk management and profit-seeking purposes in the forex market.

Private actors

In the forex market, the primary actors are traders, with many of them employed by commercial banks. These banks engage in trading activities to generate profit and also facilitate currency exchange for clients involved in international trade or investment.

EX: if Apple sells products to a German distributor and wants payment in U.S. dollars, the distributor's bank, like Deutsche Bank, handles the currency exchange. Deutsche Bank sells the euros received from the distributor in exchange for dollars, then credits Apple's U.S. bank account with the equivalent dollar amount.

Interbank trading, where banks trade currencies among themselves, is a significant part of the forex market. Approximately 75% of all forex transactions globally involve just 10 major banks, such as Citi, Deutsche Bank, and JPMorgan.

However, other actors are increasingly participating directly in the forex market. Some large corporations may trade currencies themselves to manage the costs associated with international transactions, bypassing bank fees. Additionally, nonbank financial institutions like mutual funds or asset managers may conduct forex trading operations due to their extensive overseas investments.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

GOV actions

Government authorities can influence the forex market in two primary ways.

- Complete control over the market through capital controls, where governments restrict or regulate foreign exchange transactions. This can include setting official exchange rates or even banning forex trading altogether. Although capital controls may be enforced, illicit trading often persists in black markets.

- Governments may intervene in the forex market without imposing capital controls. Central banks, for example, may fix or control forex prices through intervention, typically by buying or selling their own currency to maintain a desired exchange rate. This intervention requires maintaining foreign currency reserves, which can be costly and finite.

The effectiveness of government intervention varies, and even with strict controls, private actors continue to influence the market. Understanding how private economic motives interact with government actions is crucial for comprehending forex market dynamics.

13.4. Arbitrage and Spot Exchange Rates

Arbritage w/ 2 currencies

Arbitrage opportunities arise when there is a discrepancy in exchange rates between two locations. It’s when traders can buy a currency at a lower price in one market and sell it at a higher price in another, making a risk-free profit. However, arbitrage opportunities quickly diminish as traders exploit them, driving prices back to equilibrium.

EX : if the exchange rate for dollars to pounds is lower in New York than in London, traders would buy dollars in New York and sell them in London, increasing the demand for dollars in New York and driving up its price while simultaneously increasing the supply of dollars in London and driving down its price. Let's say you can buy a dollar for £0.50 in New York but sell it for £0.55 in London. You'd make a profit by doing this. But, as more people catch on and do the same, it evens out the prices across locations until there's no more profit to be made. Essentially, arbitrage helps keep exchange rates in check, ensuring they're similar across different markets.

Arbitage w/ 3 currencies

Triangular arbitrage involves trading between three currencies to make a profit.

EX: you start with dollars in New York, where the exchange rate is 0.8 euros per dollar. Then, you trade those dollars for euros. Next, you trade those euros for pounds in London, where the exchange rate is 0.7 pounds per euro. If you follow this path, you can calculate the resulting exchange rate between dollars and pounds.

First, you exchange $1 for euros. With the 0.8 euros per dollar, you get 0.8 euros.

Next, you exchange the euros for pounds. With the rate 0.7 pounds per euro, you get 0.7 × 0.8 = 0.56 pounds.

So, by trading through euros, you end up with 0.56 pounds for $1.

If the direct exchange rate from dollars to pounds is less favorable, say 0.5, you can use triangular arbitrage to make a riskless profit. You would trade $1 60.56 pounds via euros and then trade the 0.56 pounds for $1.12 directly. This results in a profit of $0.12.

The no-arbitrage condition for triangular arbitrage states that the direct exchange rate between two currencies must equal the product of the exchange rates involving a third currency. This ensures that there are no profit opportunities in the market.

Using the cross-rate formula E£/$NY=E£/€London×E$/€NY or

simplifies the calculation of exchange rates between two currencies without needing to know the direct exchange rates for every currency pair. It's a convenient way to determine exchange rates in practice.

Let's use an example with hypothetical exchange rates to illustrate each scenario:

Suppose we have the following exchange rates:

- USD to EUR: 1.2 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 0.8 pounds per euro

- USD to GBP (direct rate): 0.9 pounds per dollar

Now, let's consider trading $1 for pounds directly (USD to GBP) and compare it with trading through euros (USD to EUR to GBP):

- Favorable Arbitrage:

- Direct exchange rate (USD to GBP): 0.9 pounds per dollar

- Indirect exchange rate via euros (USD to EUR to GBP):

- USD to EUR: 1.2 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 0.8 pounds per euro

- Effective exchange rate (USD to GBP): 1.2×0.8=0.961.2×0.8=0.96 pounds per dollar

- Since the effective exchange rate through euros (0.96 pounds per dollar) is higher than the direct exchange rate (0.9 pounds per dollar), this is a favorable arbitrage opportunity.

- Unfavorable Arbitrage:

- Let's reverse the scenario and assume the following exchange rates:

- USD to EUR: 1.2 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 1.5 pounds per euro

- USD to GBP (direct rate): 0.8 pounds per dollar

- Direct exchange rate (USD to GBP): 0.8 pounds per dollar

- Indirect exchange rate via euros (USD to EUR to GBP):

- USD to EUR: 1.2 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 1.5 pounds per euro

- Effective exchange rate (USD to GBP): 1.2×1.5=1.81.2×1.5=1.8 pounds per dollar

- Since the effective exchange rate through euros (1.8 pounds per dollar) is lower than the direct exchange rate (0.8 pounds per dollar), this is an unfavorable arbitrage opportunity.

- Let's reverse the scenario and assume the following exchange rates:

- No-Arbitrage:

- Let's adjust the rates again:

- USD to EUR: 1.25 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 0.75 pounds per euro

- USD to GBP (direct rate): 0.9375 pounds per dollar

- Direct exchange rate (USD to GBP): 0.9375 pounds per dollar

- Indirect exchange rate via euros (USD to EUR to GBP):

- USD to EUR: 1.25 euros per dollar

- EUR to GBP: 0.75 pounds per euro

- Effective exchange rate (USD to GBP): 1.25×0.75=0.93751.25×0.75=0.9375 pounds per dollar

- Since the effective exchange rate through euros (0.9375 pounds per dollar) is equal to the direct exchange rate (0.9375 pounds per dollar), this satisfies the no-arbitrage condition. There's no opportunity for risk-free profit

- Let's adjust the rates again:

Cross rates & Vehicle currencies

Cross rates simplify currency trading by allowing currencies to be exchanged indirectly through a third currency. For instance, if someone wants to convert Kenyan shillings to Paraguayan guaranís, they might first convert shillings to U.S. dollars, then dollars to guaranís. This method is more practical than finding a direct counterparty for the exchange of shillings to guaranís.

The third currency used in such transactions, like the U.S. dollar, is known as a vehicle currency. It's not the home currency of either party involved in the trade but acts as an intermediary. Vehicle currencies are essential in international trade, with the U.S. dollar being the most commonly used, appearing in 87% of all global trades according to data from the Bank for International Settlements.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

13.5 Arbitrage & interest rates Top of Form

Arbitrage with Interest Rates

In the forex market, traders face the decision of where to invest their liquid cash balances. This choice often revolves around the interest rates offered by different currencies. For instance, a trader in New York might have to choose between placing funds in a euro deposit earning 2% interest or a U.S. dollar deposit earning 4% interest for one year. But how can she determine which option is more profitable?

The concept of arbitrage comes into play here as well. The decision to sell euro deposits and buy dollar deposits, or vice versa, drives the demand for these currencies and affects their exchange rates. However, the key concern for the trader is the exchange rate risk. While the dollar deposit offers a known return in dollars, the return from the euro deposit is in euros, which might fluctuate against the dollar over time.

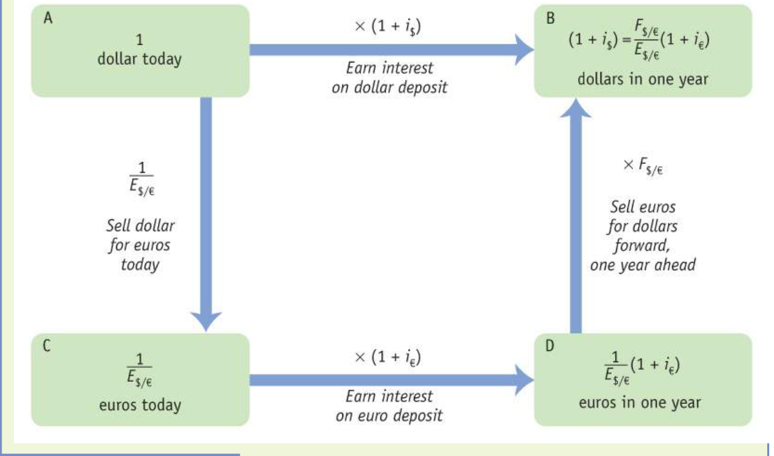

To address this risk, traders may use forward contracts to hedge their exposure to exchange rate fluctuations. This leads to two important implications known as parity conditions: covered interest parity and uncovered interest parity.

Covered Interest Parity (CIP) applies when traders use forward contracts to cover their exchange rate risk. The condition states that the dollar return from dollar deposits must be equal to the dollar return from euro deposits, adjusted for the forward exchange rate. In other words, any potential profit from arbitrage is eliminated when covered interest parity holds. This condition ensures that all exchange rate risk on the euro side is "covered" by the forward contract.

For example, if the dollar return from dollar deposits exceeds that from euro deposits, traders would advise selling euro deposits and buying dollar deposits to exploit the profit opportunity. Conversely, if the euro deposits offer a higher dollar return, traders would advise selling dollar deposits and buying euro deposits. Only when both deposits offer the same dollar return is there no expected profit from arbitrage, satisfying the covered interest parity condition.

Bottom of Form

Determining the Forward Rate

Covered interest parity (CIP) gives us insight into what determines the forward exchange rate. It's essentially a no-arbitrage condition that establishes an equilibrium where investors are indifferent between returns on interest-bearing bank deposits in two currencies, and exchange rate risk is eliminated through the use of a forward contract.

We can rearrange the CIP equation to solve for the forward rate: F$/€=E$/€1+i$1+i€

This equation allows us to calculate the forward rate if we know the spot rate (E$/€), the dollar interest rate (i$), and the euro interest rate (i€). For instance, if the euro interest rate is 3%, the dollar interest rate is 5%, and the spot rate is $1.30 per euro, then the forward rate would be calculated as $1.30 × (1.05)/(1.03) = $1.3252 per euro.

In practice, traders worldwide use this approach to set the price of forward contracts. By observing interest rates on bank deposits in each currency and the spot exchange rate, traders can calculate the forward rate. This process highlights why forward contracts are considered "derivative" contracts—their pricing is derived from the underlying spot contract, incorporating additional information on interest rates.

This leads us to a crucial question: How are interest rates and the spot rate determined? We'll explore this question shortly after examining evidence to confirm that covered interest parity indeed holds.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP) »

The alternative approach to engaging in arbitrage involves using spot contracts and accepting the risk associated with future exchange rates. By exploring this method, we can gain insight into how exchange rates are determined in the spot market.

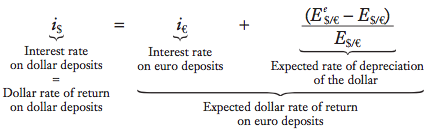

Imagine you're trading for a bank in New York and must decide whether to invest $1 in a dollar or euro bank deposit for one year. This time, you're using spot contracts only and not hedging against the risk of future exchange rates.

If you invest in a dollar deposit, your $1 will be worth (1 + i$) in one year, representing the dollar return, as before.

On the other hand, if you invest in a euro deposit, your $1 will be converted to euros at the spot rate today, resulting in 1/E$/€ euros. With interest, these euros will be worth (1 + i€)/E$/€ euros in one year. However, you'll need to convert these euros back into dollars using a spot contract at the prevailing exchange rate, which is forecasted as E$/€e, the expected exchange rate.

Based on this forecast, you expect that the (1 + i€)/E euros you'll have in one year will be worth (1 + i€)E$/€e/E dollars. This represents the expected dollar return on euro deposits.

In essence, traders like you face exchange rate risk and must make forecasts of future spot rates to assess their expected returns accurately. This method, known as Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP), considers the expected returns of bank deposits in different currencies without hedging against exchange rate risk.

Uncovered interest parity (UIP) provides a theory of what determines the spot exchange rate, as it establishes an equilibrium where investors are indifferent between the returns on unhedged interest-bearing bank deposits in two currencies, without the use of forward contracts.

We can rearrange the UIP equation and solve for the spot rate: E$/€=E$/€e1+i€1+i$

- This equation tells us that if uncovered interest parity holds, today's spot rate can be calculated if we know the expected future exchange rate (E$/€e), the dollar interest rate (i$), and the euro interest rate (i€).

EX: if the euro interest rate is 2%, the dollar interest rate is 4%, and the expected future spot rate is $1.40 per euro, then today's spot rate would be 1.40×1.021.04=$1.37311.40×1.041.02=$1.3731 per euro.

However, this leads to more questions: How can the expected future exchange rate (E$/€e) be forecasted? And how are the two interest rates (i$ and i€) determined?

In the following chapters, we'll delve into these questions to further develop our understanding of exchange rate determination. We'll explore the determinants of the expected future exchange rate (�$/€�E$/€e) and develop a model of exchange rates in the long run. Additionally, we'll examine the determinants of the interest rates (i$ and i€). Understanding these concepts is crucial for comprehending exchange rates both in the long run and the short run.

Evidence on Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP)

Uncovered interest parity (UIP) and covered interest parity (CIP) are two similar yet distinct concepts that describe equilibrium conditions in the forex market. While CIP uses the forward rate, UIP relies on the expected future spot rate. However, under certain assumptions, both CIP and UIP imply that the forward rate and the expected future spot rate should be equal.

Mathematically, this can be expressed as: F$/€ = E$/€e

Where:

- F$/€ is the forward rate.

- E$/€e is the expected future spot rate.

This equivalence suggests that in equilibrium, investors should be indifferent between using the forward rate or waiting for the future spot rate, assuming they do not consider risk.

Testing UIP involves comparing the forward premium (the difference between the forward and spot rates) with the expected rate of depreciation (the change in the spot rate over time). If UIP holds, the forward premium should equal the expected rate of depreciation.

Forward premium=E$/€F$/€−1

Expected rate of depreciation= E$/€E$/€e−1

If the forward rate equals the expected future spot rate, then the forward premium should equal the expected rate of depreciation.

Empirical tests of UIP involve surveys where forex traders report their expectations. Despite some deviations from the ideal relationship, the overall evidence suggests a strong correlation between the forward premium and the expected rate of depreciation, supporting the concept of UIP. However, deviations may occur due to factors such as sampling errors, market frictions, and risk aversion among traders. Overall, the evidence provides some support for UIP, although it is not without limitations and challenges in real-world applications.

Top of Form

Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP)

provides a fundamental principle in international macroeconomics, offering insight into how the spot exchange rate is determined. However, for practical purposes, a simplified approximation can often suffice.

The concept behind this approximation is straightforward: Holding dollar deposits earns dollar interest, while holding euro deposits provides euro interest and potential gains or losses due to changes in the euro's value relative to the dollar. To maintain investor indifference between dollar and euro deposits, any shortfall in euro interest must be compensated by an expected gain from euro appreciation or dollar depreciation.

Formally, the UIP approximation equation is expressed as follows:

∆E$/€e/E$/€ = (E$/€e − E$/€)/E$/€

Where:

- i$ is the interest rate on dollar deposits.

- i€ is the interest rate on euro deposits.

- Δ$/€$/€E$/€ΔE$/€e represents the expected rate of change in the euro's value relative to the dollar, which approximates the expected rate of dollar depreciation.

This equation states that the home interest rate equals the foreign interest rate plus the expected rate of depreciation of the home currency.

EX: Suppose the dollar interest rate is 4% per year and the euro interest rate is 3% per year. To uphold UIP, the expected rate of dollar depreciation over a year should be 1%. In this scenario, a dollar investment converted into euros would grow by 3% due to euro interest, plus an additional 1% due to euro appreciation. Thus, the total dollar return on the euro deposit approximates the 4% offered by dollar deposits.

In summary, whether in its exact form or its simplified approximation, uncovered interest parity dictates that expected returns, when expressed in a common currency, should be equal across different markets.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Bottom of Form

Chapter 14 : Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run

14.1. Exchange rates + prices in the LR

Arbitrage not only occurs in international markets for financial assets but also international markets for goods .

The law of one price

The Law of One Price (LOOP) basically says that identical goods sold in different places should have the same price when you compare those prices in a common currency, assuming there are no barriers like transportation costs or tariffs.

EX: Suppose diamonds of the same quality are priced at €5,000 in Amsterdam, and the exchange rate is $1.20 per euro. According to LOOP, if we convert the euro price to dollars, it should be the same as the price of diamonds in New York.

Here's why prices should be the same:

- If diamonds were cheaper in New York, people would buy them there and sell them in Amsterdam for a profit.

- If diamonds were cheaper in Amsterdam, people would buy them there and sell them in New York for a profit.

LOOP ensures that there are no such profitable opportunities because arbitrage (buying low and selling high) keeps prices aligned across markets.

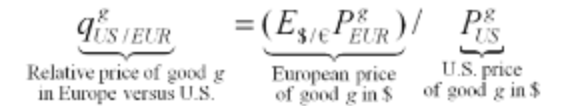

Mathematically, we can express LOOP as the ratio of the price of a good in one location to its price in another location, both in the same currency. If this ratio equals 1, it means prices are the same in both places.

Mathematically, we can express LOOP as the ratio of the price of a good in one location to its price in another location, both in the same currency. If this ratio equals 1, it means prices are the same in both places.

P![]() : good’s price in the U.S. P

: good’s price in the U.S. P![]() : good’s price in Europe.

: good’s price in Europe.

q![]() : the rate at which goods can be exchanged.

: the rate at which goods can be exchanged.

E![]() : the rate at which the currencies of the two countries can be exchanged.

: the rate at which the currencies of the two countries can be exchanged.

The law of one price is essential in understanding exchange rates. If it holds true, it means that the exchange rate should be equal to the ratio of prices of goods in two countries when expressed in their respective currencies.

Purchasing power parity

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) is like the big sibling of the Law of One Price. While the Law of One Price focuses on comparing the prices of single goods across different locations, PPP looks at the prices of entire baskets of goods.

Here's a breakdown of PPP:

- Price Level:

- We define a price level (P) in each location as an average of prices for all goods in a basket, using the same goods and weights in both places.

- Let's call the basket's price in the United States PUS and in Europe PEUR. If the Law of One Price holds for each good in the basket, it will also hold for the basket's overall price.

- Relative Price (qUS/EUR):

- We calculate the relative price of the two baskets of goods in each location, denoted qUS/EUR.

- This relative price tells us how the basket's price in Europe compares to its price in the United States when expressed in a common currency (like dollars).

- Possible Outcomes:

- Similar to the Law of One Price, there are three outcomes for PPP:

- The basket is cheaper in the United States.

- The basket is cheaper in Europe.

- The basket costs the same in both locations (qUS/EUR = 1).

- Only when the basket costs the same in both places is there no opportunity for profitable arbitrage. This is when PPP holds true.

- Similar to the Law of One Price, there are three outcomes for PPP:

EX: the European basket costs €100, and the exchange rate is $1.20 per euro.

- For PPP to hold, the U.S. basket would have to cost $120 (1.20 × €100).

In summary, PPP states that price levels in different countries should be equal when expressed in a common currency. This concept is crucial in understanding how exchange rates and price levels interact on a broader scale.

Top of Form

The real exchange rate Bottom of Form

The Real Exchange Rate (q) is like the big sibling of the relative price of individual goods (qg). It tells us how many baskets of goods from one country are needed to purchase one basket from another country.

Here's a breakdown of the Real Exchange Rate:

- Definition:

- The real exchange rate qUS/EUR = E$/€PEUR = PUS tells us how many U.S. baskets are needed to buy one European basket.

- It's a macroeconomic concept that focuses on comparing the overall prices of baskets of goods between countries.

- Understanding the Numerator and Denominator:

- In our example, qUS/EUR = E$/€PEUR = PUS is called the home country or U.S. real exchange rate. It represents the price of the European basket in terms of the U.S. basket.

- It's important to distinguish between nominal exchange rates (like how many dollars for one euro) and real exchange rates (like how many U.S. baskets for one European basket).

- Terminology:

- Similar to nominal exchange rates, we have terminology for changes in real exchange rates:

- If the real exchange rate rises (more U.S. baskets are needed for one European basket), it's called a real depreciation for the home country.

- If the real exchange rate falls (fewer U.S. baskets are needed for one European basket), it's called a real appreciation for the home country.

- Similar to nominal exchange rates, we have terminology for changes in real exchange rates:

In simple terms, the Real Exchange Rate helps us understand how the prices of baskets of goods in different countries relate to each other. If more U.S. goods are needed to buy one European basket, it's a sign of real depreciation for the U.S. Conversely, if fewer U.S. goods are needed, it's a sign of real appreciation.

Absolute ppp and the real exchange rate

Absolute Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) states that the real exchange rate equals 1. This means that all baskets of goods should have the same price when expressed in a common currency, making their relative price 1.

When the real exchange rate is below 1, it means that foreign goods are relatively cheap compared to home goods. In this case:

- The home currency (like the dollar) is considered strong.

- The foreign currency (like the euro) is considered weak.

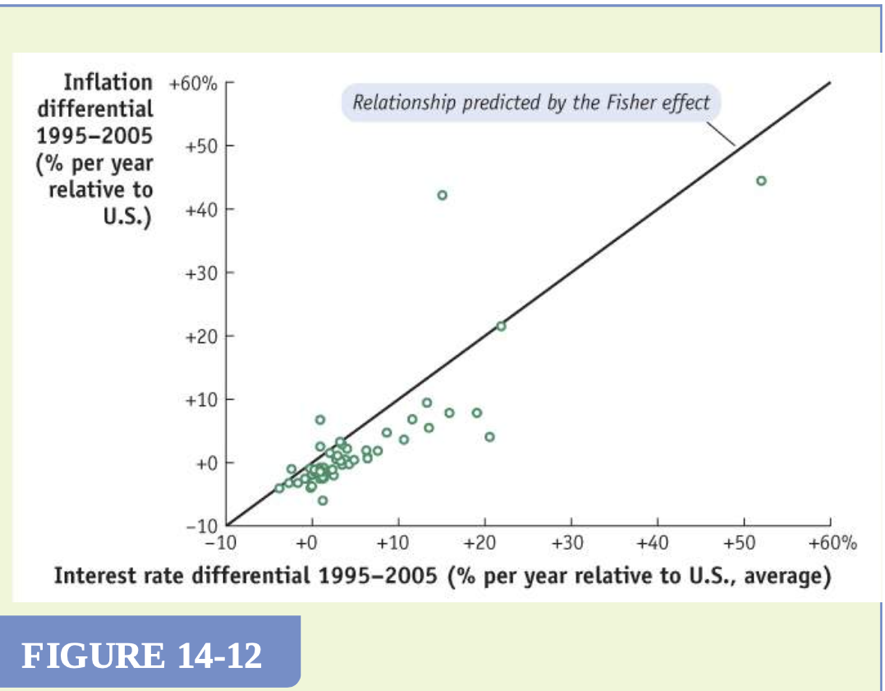

- We say that the foreign currency is undervalued by a certain percentage (x%).