Chemistry 12HL Reactivity 1-3

Reactivity 1

1.1: Measuring enthalpy changes

Heat transfers

energy is a measure of the ability to do work

to move an object against an opposing force

can be transferred through heat, light, sound, electricity, etc.

heat - form of energy transfer that occurs as a result of a temperature difference

when heat is transferred to a system, the average KE of molecules and the temperature are increased → KE is more dispersed among the particles

System and Surroundings

system → area of interest

open system → energy/matter can be exchanged with surroundings

closed system → energy can be exchanged but matter cannot

isolated system → energy and matter cannot be exchanged with surroundings

surroundings → everything else in the universe

Enthalpy of a system

enthalpy → chemical potential energy of a system

system acts as a reservoir of chemical potential energy/enthalpy

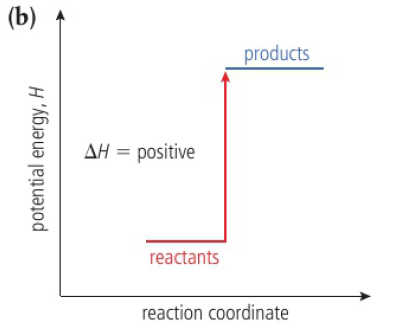

when heat is added to a system from its surroundings, its enthalpy increases (+ΔH)

when heat is given out by a system, its enthalpy decreases (-ΔH)

ΔH = change in enthalpy

endothermic:

exothermic:

Direction of a reaction

there is a natural direction for change

to lower stored/potential energy (exothermic)

chemicals change in a way that reduces their chemical potential energy

products of an exothermic reaction are more stable than the reactants

stability is a relative term

most combustion reactions are exothermic

the energy needed to break the bonds is less than the energy produced as bonds form

activation energy → minimum KE to react

some bonds must be broken before new bonds are formed

Measuring enthalpy changes

standard enthalpy change (ΔHꝊ)

pressure → 100kPA

concentration of 1mol/dm³ for all solutions

all substances in their standard states

usually 298K as temperature

thermochemical equations

ex: CH4(aq) + 2O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2H2O(l) ΔHreaction = -890kJ/mol

1 mole of CH4 reacts with 2 moles of O2 to produce 1 mole of CO2 and 2 moles of H2O and releases 890kJ of heat energy

Calculating enthalpy changes

absolute temperature (K) is a measure of the average KE of the particles

more/less particles with same heat energy added will result in a different temperature

q=mcΔT

q: heat added (J), m: mass (g), c: specific heat capacity (J/gK), ΔT: temperature change (K)

specific heat capacity → heat needed to increase the temperature of a unit mass of a substance by 1K

depends on the number of particles present

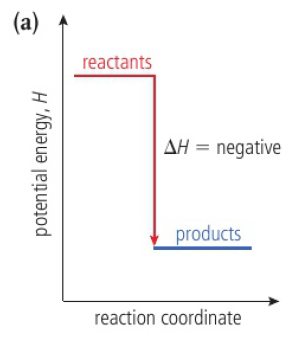

Combustion: enthalpy changes

enthalpy change of combustion (ΔHc) can be determined using this apparatus:

heat absorbed by the water can be calculated from the temperature change and mass

heat absorbed by calorimeter can also be calculated using c

temperature of the water increases due to heat released from the combustion reaction

heat released as ethanol and oxygen turn into carbon dioxide and water

there is a decrease in enthalpy in this reaction

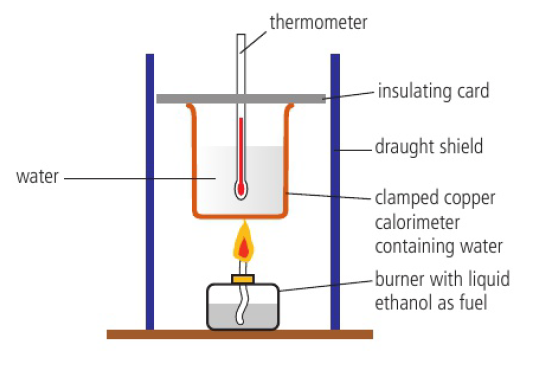

Reaction in the solution: enthalpy changes

calculated by carrying out the reaction in an isolated system

heat released/absorbed by reaction can be measured from the temperature change in the water (solvent)

calorimeter made from an insulator to maximize heat transferred to water by reaction

error → all heat produced in the reaction is absorbed by the water

heat is lost from the system as soon as its temperature rises above the temperature of its surroundings

by extrapolating the cooling section to the time when the reaction started, it now creates some allowance for heat loss, so now we can assume:

no heat loss from system

all heat goes from reaction to water

solution is dilute

water has density of 1g/cm³

1.2: Energy Cycles in Reactions

energy changes occur when bonds are broken or new bonds are formed

energy is required to separate particles and energy is released when particles come together

net enthalpy change is the difference between these two energy contributions

law of conservation of energy → energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transferred

Bond enthalpy

bond enthalpy → energy needed to break one mole of bonds in gaseous molecules in standard conditions

ex: Cl2(g) → 2Cl(g) ΔH=+242kJ/mol

breaking bonds is an endothermic process (positive enthalpy change)

bond enthalpies differ, it may be harder to break depending on environment

to compare bond enthalpies which occur in different environments, average bond enthalpies will be used

all bond enthalpies refer to reactions in the gaseous state

any enthalpy changes resulting from the formation/breaking of intermolecular forces are not included

multiple bonds (involves more bonding electrons) generally have higher bond enthalpies and shorter bond lengths

the more polar the bond, the stronger it will be

making bonds is an exothermic process (negative enthalpy change)

the same amount of energy is absorbed when a bond is broken as is released when a bond is formed

Energy changes in reactions

ex: complete combustion of methane

CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O

energy is taken in to break the C-H and O=O bonds in the reactants

energy is given out when the C=O and O-H bonds are formed in the products

reaction is exothermic overall as the bonds formed are stronger than those broken

opposite would be true for endothermic reactions

ΔH = ΣEbonds broken - ΣEbonds formed

some reactants need to be given an initial energy (activation energy) before they will react

some bonds in the reactants must break before new bonds can form

rate of some reactions can be explained by the relative bond enthalpy of the bonds broken

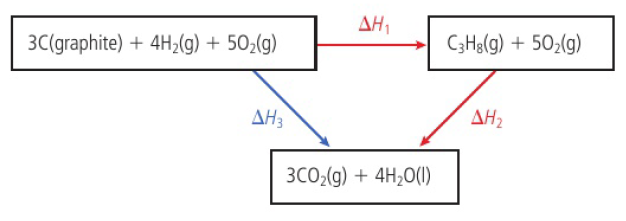

Hess’s Law

the enthalpy change for any chemical reaction is independent of the route, provided the same starting conditions and final conditions, and reactants and the products, are the same

ΔH3=ΔH1+ΔH2

due to the conservation of energy

can be used to find enthalpy change of reactions that cannot be measured directly

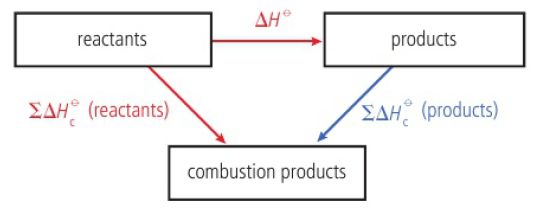

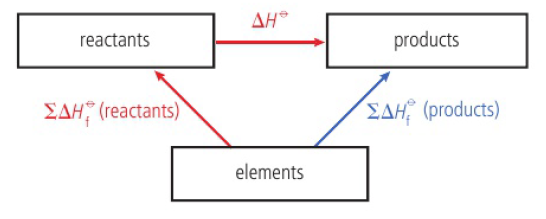

Calculating enthalpy changes

standard enthalpy change of combustion (ΔHcꝊ)

enthalpy change that occurs when one mole of the substance burns completely under standard conditions

can be measured by calculating temperature change of water heated by the combustion

reactants - products

standard enthalpy of formation (ΔHfꝊ)

enthalpy change that occurs when one mole of the substance is formed from its elements in their standard states

standard measurements taken at a specific temperature (usually 298K) and pressure of 1×105 Pa

standard state of an element is its most stable form under these conditions

products - reactants

Lattice enthalpies

first ionization energy (ΔHiꝊ) → energy needed to form the positive ion of a gaseous atom

endothermic process (pulling electron away from electrostatic force)

first electron affinity (ΔHeꝊ) → enthalpy change when one mole of gaseous atoms attracts one mole of electrons

exothermic process (electron is attracted to positively charged nucleus)

lattice enthalpy (ΔHlatꝊ) → formation of gaseous ions from one mole of a solid crystal breaking into gaseous ions

ex: NaCl(s) → Na+(g) + Cl-(g) ΔHlatꝊ=+790kJ/mol

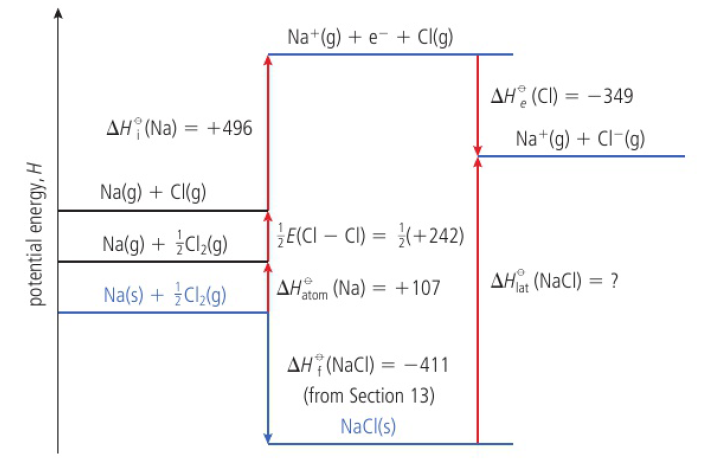

Born-Haber cycles

formation of an ionic compound from its elements is supposed to take place in a number of steps, including the formation of the solid lattice from its constituent gaseous ions

from Hess’s Law, the enthalpy change for the overall formation of the solid must equal the sum of the enthalpy changes accompanying the individual steps

ex: Na(s)+1/2 Cl2(g) → NaCl(s) ΔHf(NaCl)=-411kJ/mol

Na(s)→Na(g) sodium is atomized ΔHatom(Na)=+107kJ/mol

½ Cl2(g)→Cl(g) 1/2E(Cl-Cl)=1/2(+242KJ/mol) E=bond enthalpy

Na(g)→Na+(g)+e- ΔHi(Na)=+496kJ/mol

Cl(g)+e-→Cl-(g) ΔHe(Cl)=-349kJ/mol

Na+(g)+Cl-(g)→NaCl(s) -ΔHlat=+786kJ/mol → sum

1.3: Energy from fuels

Combustion reactions

many substances undergo combustion reactions when heated in oxygen

s-block metals form ionic oxides (basic)

p-block non-metals generally form covalent oxides (acidic)

many hydrocarbons/alcohols are used as fuels as their combustion reactions release energy at a reasonable rate to be useful

high activation energy → do not spontaneously combust, safe transport and storage

kinetically stable

complete combustion of organic compounds break the carbon chain → results in CO2 + H2O and a release in (a lot of) heat energy

complete combustion → products are fully oxidized

when oxygen supply is limited, incomplete combustion occurs

incomplete combustion of organic compounds

if the air supply is limited/compound has high carbon content, incomplete combustion occurs

results in carbon monoxide / carbon (soot)

releases less heat than complete combustion

Fossil fuels

an ideal fuel releases significant amounts of energy at a reasonable rate and produces minimal pollution

fossil fuels are non-renewable → used at a rate faster than they are replaced

liquid fuels have significantly greater energy densities than gases (per unit volume)

fossil fuels were formed by the reduction of biological compounds

oxygen is lost from biological molecules which generally result in hydrocarbons

coal → most abundant, 80-90% carbon (by mass)

crude oil → mixture of straight-chain and branched-chain saturated alkanes, cycloalkanes, and aromatic compounds, used as fuel for transportation and electricity

natural gas → primarily methane, cleanest fossil fuel → low carbon content

coal

advantages

cheap, abundant

longest lifespan (compared to other fossil fuels)

can be converted into synthetic liquid fuels and gases

safer than nuclear power

ash produced can be used to make roads

disadvantages

contributes to global warming (CO2 emissions)

contributes to acid rain (SO2)

produces particulats (electrostatic preceptors can remove most of these)

difficult to transport

waste can lead to visual + chemical pollution

mining is dangerous

petroleum

advantages

easily transported in pipelines/tankers

convenient fuel for use in cars → volatile, burns easily

high enthalpy density

sulfur impurities can be easily removed

disadvantages

limited lifespan and uneven world distribution

contributes to acid rain and global warming

transport can lead to pollution

carbon monoxide is produced through incomplete combustion (pollutant)

photochemical smog is produced

natural gas

advantages

higher specific energy

clean and easily transported

does not contribute to acid rain

disadvantages

limited supplies

contributes to global warming

risk of explosion (leaks)

Combustion of alkanes

increase in %carbon content down the homologous series suggests that incomplete combustion increases with length of the carbon chain

mass of CO2 produced per unit mass of fuel increases with %carbon content

the higher %carbon content (and lower %hydrogen), the lower the specific energy

The greenhouse effect

it is estimated that CO2 contributes to about 50% of global warming

greenhouse gases allow shortwave radiation from the Sun to pass through the atmosphere but absorb the longer wave infrared radiation that was re-radiated from Earth’s surface

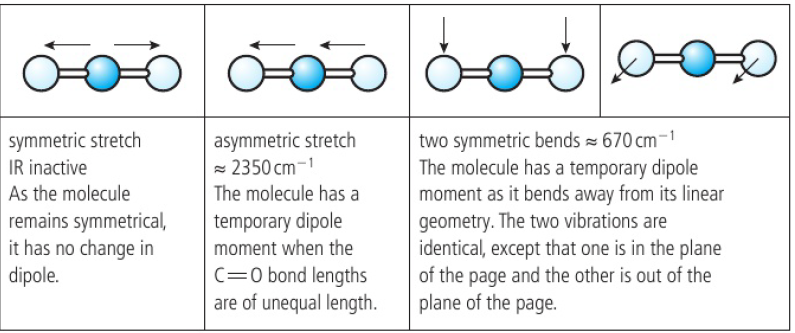

CO2 is a GHG as its molecules increase their vibrational energy by absorbing IR radiation

3 of the vibrational modes of CO2 are IR active → dipole changes as it vibrates

molecules then re-radiate the absorbed energy back to Earth’s surface → global warming

greenhouse effect increased as CO2 levels increased, causing (due to change in temperature):

changes in agriculture (crop yields)

changes in biodistribution due to desertification and loss of cold-water fish habitats

rising sea levels caused by thermal expansion and melting of polar ice caps/glaciers

Biofuels

photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy

chlorophyll (green pigment) absorbs solar energy which is used in this reaction:

6CO2(g) + 6H2O(l) → C6H12O6(s) + 6O2(g)

carbon dioxide + water → (using solar energy) glucose + oxygen

biofuels → produced from the biological fixation of carbon over a short period of time

ethanol is a liquid biofuel → used in internal combustion engines

made from biomass by fermenting plants high in starches and sugars

C6H12O6 → 2C2H3OH + 2CO2

process done at around 37C in absence of oxygen by yeast (provides enzyme)

advantages (when used in gasohol: 10% ethanol, 90% unleaded gasoline)

renewable, lower emissions of CO and nitrogen oxides, decreases dependance on oil)

disadvantages

ethanol absorbs water (it can form hydrogen bonds) so it seperates from the hydrocarbons

can cause corrosion

methane → made form bacterial breakdown of plant mateiral in absence of oxygen

C6H12O6 → 3CO2 + 3CH4

advantages of biofuels

cheap + readily available

renewable (if crops/trees are replanted)

less polluting than fossil fuels

disadvantages of biofuels

uses land → can be used for other purposes (ex: growing food)

high cost of harvesting and transportation

takes nutrients from soil / uses large amounts of fertilizers

lower specific energy than fossil fuels

Fuel cells

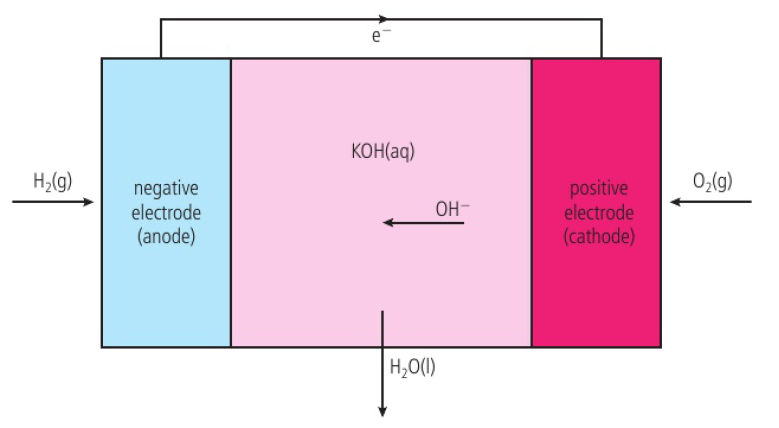

hydrogen fuel cell

H2(g) + ½ O2(g) → H2O(l)

this is a redox reaction (transfer of electrons from hydrogen to oxygen)

can produce an electric current if reactants are physically seperated

hydrogen fuel cell operates with either an acidic or alkaline electrolyte

in fuel cells, reactants are continuously supplied to different electrodes

hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell → alkaline electrolyte (most commonly used)

fuel cell will function as long as H2 and O2 are supplied

electrodes are often made of porous carbon with added transition metals (ex: nickel)

KOH (potassium hydroxide) provides the OH- ions that are transferred across the cell

problem: hydrogen gas must be extracted from other sources so might not be renewable

methanol fuel cell; DMFC → Direct Methanol Fuel Cell

methanol → stable liquid at normal environmental conditions, high energy density, easy to transport

DMFC → fuel is oxidized under acidic conditions on a catalytic surface to form CO2

H+ ions formed are transported across a proton exchange membrane from anode to cathode where they react with oxygen to form water

electrons are transported through an external circuit from anode to cathode

water is consumed at the anode and produced at the cathode

difference between fuel cells and primary voltaic cells:

fuel cells do not run out

fuel is supplied continuously to the cell as it is oxidized

1.4: Entropy and spontaneity

second law of thermodynamics: matter and energy tend to disperse and become more dispersed

entropy (S) → degree of dispersal of matter and energy of a system

spontaneous change → dispersion occurs naturally without work

Entropy

the natural tendency to change can be reversed if work is done

entropy → measure of dispersal/distribution of matter/energy in a system

ordered states with small energy distribution → low entropy

ex: gas particles concentrated in a small volume

disordered states with high energy distribution → high entropy

ex: gas particles dispersed throughout

as time moves forward, matter and energy become more dispersed → increases total entropy of universe

Predicting entropy changes

doubling number of particles also increases opportunity for matter/energy to be dispersed

doubling amount of a substance → entropy doubles

solid state → most ordered state with least dispersal → low entropy

increasing entropy: solid→liquid, solid→gas, liquid→gas

decreasing entropy: liquid→solid, gas→solid, gas→liquid

change due to number of particles (in gaseous state) is usually greater than any possible factor

Absolute entropy

entropy of a substance under standard conditions → section 13

all entropy values are positive

a perfectly ordered solid at absolute zero has an entropy of zero

Calculating entropy changes

calculated using differences between total entropy of the products and total entropy of the reactants

ΔS = ΔSproducts - ΔSreactants

calculations similar to enthalpy changes

entropy values are absolute values → always positive

Entropy changes of surroundings

to consider the total entropy change of a reaction, the entropy change in surroundings must also be considered

in an exothermic reaction, heat is transferred to the surroundings → general dispersal of energy

entropy of the surroundings increases as heat given out by reaction increases diispersal of surroundings

change in entropy of surroundings = enthalp ychange in the system x -absolute temperature

ΔSsurroundings = -ΔHsystem/T

exothermic reaction (-ΔH) increases entropy of surroundings

Calculating total entropy changes

second law of thermodynamics says that for a spontanous change:

ΔStotal = ΔSsystem + ΔSsurroundings > 0

ΔStotal = ΔSsystem - ΔHsystem/T > 0

endothermic reactions occur if change in entropy of system can compensate for negative entropy change of surroundings produced as the heat is transferred from surroundings to the system

strongly endothermic reactions are possible because there is a very large increase in dispersal of matter and entropy of the system

order may increase in local areas but only at the expense of greater disorder elsewhere

for chemical reactions, neither ΔHsystem or ΔSsystem can reliably be used to predict the feasability of a reaction

Gibbs energy

criterion or feasability of a reaction is given by:

ΔStotal = ΔSsystem - ΔHsystem/T > 0

ΔGsystem = ΔHsystem - TΔSsystem = -TΔStotal < 0

ΔGsystem → Gibbs energy

must be negative for a spontaenous process

for spontaneity, reaction must have ΔGsystem < 0

measure of quality of energy available

measure of energy free to do work rather than leave as heat

spontaneous reactions have negative Gibbs energy because they can do useful work

it is not essential for all heat to be transferred to surroundings to produce the necessary increase in the total entropy

enough energy must be transferred to surroundings to compensate for entropy decrease in the system, but the remaining energy is available to do work

this is the amount of energy that can be converted to electrical energy in a fuel cell

necessary energy transferred to surroundings = -TΔSsystem

energy available to do work = -ΔHsystem + TΔSsystem = -ΔGsystem

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

ΔG is related to total energy change and this is just a reformulation of the 2nd law of thermodynamics

ΔG takes into account direct entropy change from transformation of chemicals in the system and indirect entropy change of surroundings resulting from the transfer of heat energy

ΔHsystem < TΔSsystem (T is always positive)

at low temperatures (TΔSsystem=0), this condition is met (exothermic) as ΔHsystem<0

endothermic reactions (positive ΔSsystem) can be spontaneous at higher temperatures

TΔSsystem > ΔHsystem

temperature Tspontaneous at which an endothermic reaction becomes spontaneous can be determined from:

Tspontaneous * ΔSsystem = ΔHsystem

Tspontaneous = ΔHsystem/ΔSsystem

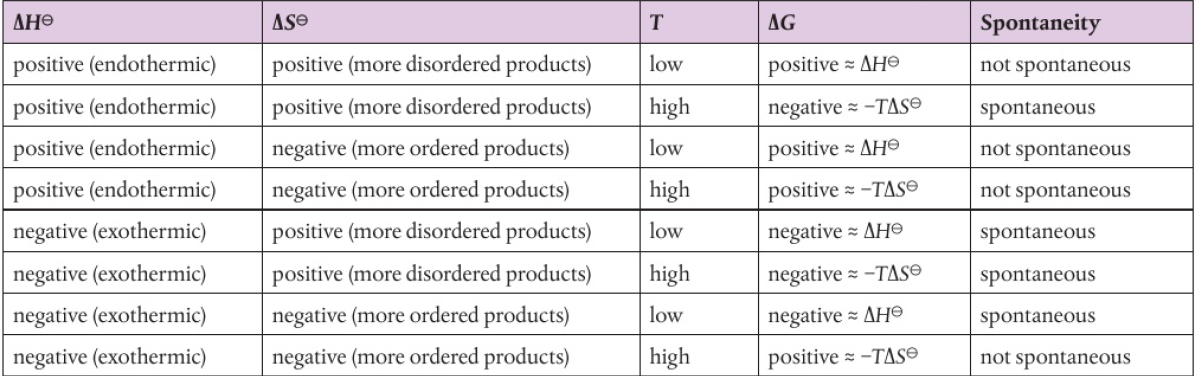

The effect of ΔH, ΔS, and T on spontaneity of the reaction

ΔGsystem = ΔHsystem - TΔSsystem

if ΔG<0, reaction is spontaneous so:

if ΔHsystem > TΔSsystem, reaction is spontaneous

so if T is high, most likely not spontaneous makes ΔHsystem is high

GIbbs energy and equilibrium

only reactions where all reactants are formed into products have been considered

equilibrium mixture when ΔG=0

spontaneous reactions only occur when ΔG<0, so when ΔG=0

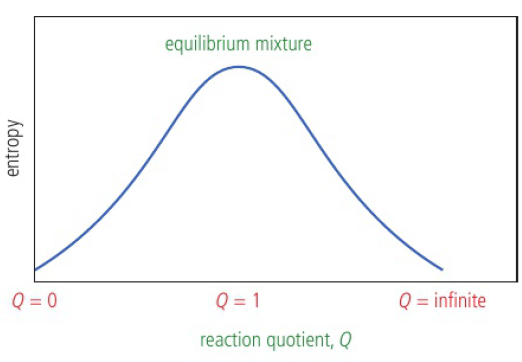

a mixture of reactant and product has higher entropy than pure samples

total entropy reaches a maximum when reactant = product

reaction quotient (Q) → ratio of products to reactants

ex: Q=[products]/[reactants] so at beginning, Q=0 and at the end, Q=infinity

equilibrium mixture when ΔG<0 (negative)

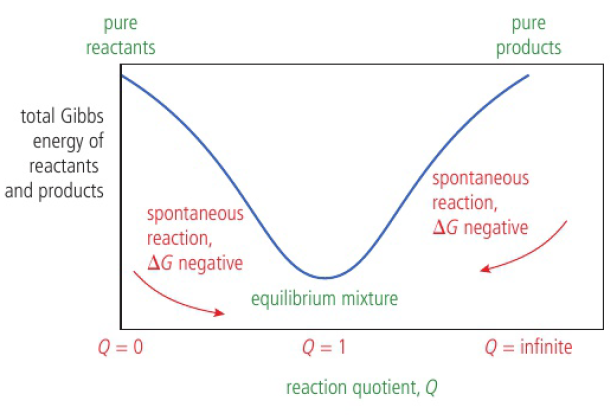

at beginning of reaction, total Gibbs energy of reactants > products so reaction proceeds in forward direction and Q increases (products increase, reactants decrease)

as reaction proceeds, Gibbs energy (system) decreases until equilibrium is reached (Q=K)

once equilibrium is reached, all possible changes are not likely to happen (ΔG increases)

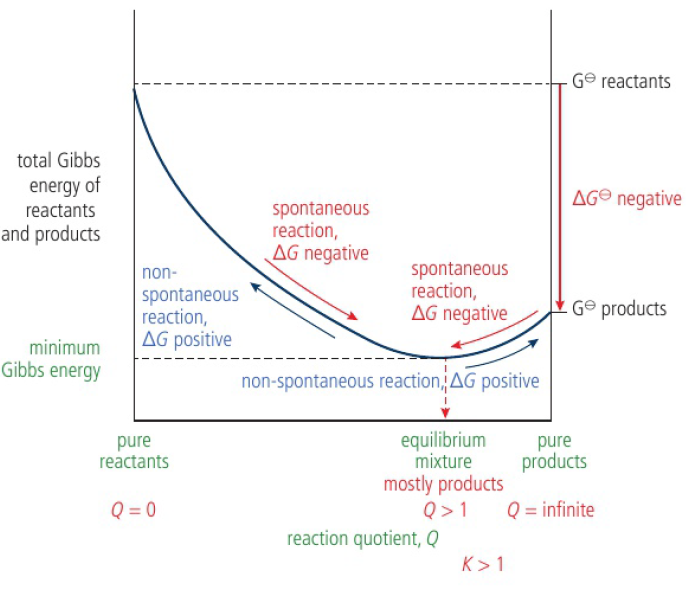

position of equilibrium corresponds to a mixture with more products than reactants

minimum Gibbs energy → equilibrium state, net reaction stops

relative amounts of reactants and products are at equilibrium

composition of equilibrium mixture is determined by the difference in Gibbs energy between reactants and products

K=[productseqm]/[reactantseqm] > 1 when ΔG<0

The equilibrium constant K

relationship between K (equilibrium constant) and ΔG (change in Gibbs energy)

so ΔG=-RT * lnK

useful when K is difficult to measure directly

ex: reaction is too slow to reach equilibrium/amounts of components are too small to measure

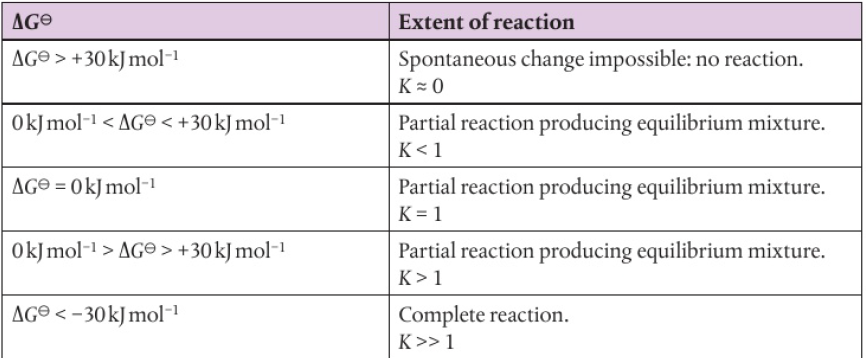

relationship between ΔG and extent of reaction:

2.1: How much? The amount of chemical change

Using chemical equations to find volumes of gaseous reactants and products

Avogadro’s Law → equal amounts of all gases measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules

equal number of particles of all gases occupy equal volumes

V has a direct relationship with n

volume occupied by one mole of any gas (molar volume, Vm) must be the same for all gases when measured under the same temperature and pressure

at STP, one mole of gas has a volume of 22.7dm³/mol

STP → OC (273K) and 100kPa

increase in temperature = increase in molar volume

increase in pressure = decrease in molar volume

number of moles of gas (n) = volume/molar volume

Titration

uses volumetric analysis to find unknown volumes or concentrations

pipette used to measure known volume into a conical flask

other solution put into a burette

point at which the two solutions have reacted completely → equivalence point

known when indicator changes color at the end point

titre → volume needed to reach equivalence point

Back titration

done in reverse by returning to the end point after it has passed

used when end point is hard to identify or when one of the reactants is impure

known excess of one reactant is added to reaction mixture, and unreacted excess is then determined by titration against a standard solution

reacting amount is determined by subtracting the amount of unreacted reactant from its original amount used

Limiting reactant and theoretical yield

limiting reactant → reactant that determines the quantity of product

always the one fully used up, other reactants are added in excess

theoretical yield → maximum amount of product obtainable (assuming 100% of limiting reactants is used)

usually expressed in grams or moles

Percentage yield

theoretical yield assumes that chemical reactions have no loss, waste, or impurities

experimental yield → actual yield with factors taken into account

factors that may cause experimental yield to be lower than the theoretical yield:

side reactions occuring

decomposition of reactants and/or products

loss of product during purification

reversible chemical reactions preventing process completion

factors that may cause experimental yield to be higher than the theoretical yield:

impurities in a product

when a product has not been fully dried

factors that impact experimental yield in both directions (depending on type of reaction):

an incomplete reaction

percentage yield = experimental yield/theoretical yield * 100

Atom economy

Green Chemistry → sustainable design of chemical products and chemical processes

aims to minimize use of chemical substances that are hazardous to human health / the environment

percentage yield does not give a quantity of waste produced

atom economy is maximized by turning as much reactant atoms into products

% atom economy = molar mass of desired product / molar mass of all reactants * 100

efficient processes have high atom economies → uses fewer resources and generates less waste

2.2: How fast? The rate of chemical change

Rate of reaction

rate of reaction → rate of change in concentration

as the reaction proceeds, reactants are converted into products

concentration of reactants decrease and concentration of products increase

rate of reaction (moldm³/s)= increase in product concentration / time taken = decrease in reactant concentration / time taken

if the line is a curve, use the gradient of the tangent

rate of reaction is not constant, but is greatest at the start and decreases over time

Measuring rate of reaction

change in volume of gas produced

used if one of the products is a gas

collecting the gas and measuring change in volume at regular time intervals

using a gas syringe or displacement of water in an inverted burette

displacement method can only be used if gas collected has low solubility in water

change in mass

if one of the products is a gas, this can be done by setting the reaction on a scale

does not work if the gas is hydrogen → too light

change in transmission of light: colorimetry/spectrophotometry

used if one of the reactants/products is colored (so gives characteristic absorption in the visible region)

sometimes indicator is added to make it a colored compound

colorimeter/spectrophotometer measures the intensity of light transmitted by reaction components

rate of product formation → change in absorbance

change in concentration → titration

quenching → a substance is introduced that effectively stops the reaction, obtaining a “freeze frame” shot

done to avoid chemically changing the reaction mixture

samples are taken from the reaction mixture at regular time intervals and analyzed by titration

titration takes time, during which the reaction would proceed → quench

change in concentration using conductivity

total electrical conductivity of a solution depends on the total concentration of its ions and charges

measured using a conductivity meter

non-continuous methods of detecting change during a reaction: ‘clock reactions’

measure time it takes for the reaction to reach a certain chose point

uses time as the dependent variable

limitation: only gives average rate of reaction

Collision theory

particles in a substance move randomly as a result of their kinetic energy

not all particles will have the same kinetic energy, but instead a range

therefore the measurement is an average

increasing temperature = increasing average kinetic energy of particles

kinetic theory of matter (S1.1)

Maxwell-Boltzman energy distribution curve

DIAGRAM HERE

the number of particles having a specific value of kinetic energy (or probability of that value occuring) against values of kinetic energy

area under the curve → total number of particles in sample

nature of collisions between particles

when reactants are placed together, their kinetic energy cause them to collide

energy from collisions may cause bonds to break and new bonds to form

as a result, products ‘form’ and the reaction stops

rate of reaction depends on the number of successful collisions which form products

successful collisions depend on:

energy of collision

geometry of collision

energy of a collision

particles must have the required activation energy (Ea) necessary for overcoming repulsion between molecules, and often breaking bonds in reactants

when Ea is supplied, reactants achieve the transition state from which products can form

activation energy is thus an energy barrier for the reaction → different for all reactions

Ea → threshold value

if you pass, you may react

DIAGRAM HERE → activation energy

particles with Ek>=Ea will collide successfully

particles with Ek<Ea may still collide, but unsuccessfully

therefore, rate of reaction depends on proportion of particles that has Ek>Ea

DIAGRAM HERE → Maxwell curve activation energy

generally, reactions with high activation energy will proceed more slowly as fewer particles will have the required energy for a successful collision

geometry of a collision

DIAGRAM HERE → different collisions

because collisions between particles are random, there are many likely orientations → only some are successful

therefore, rate of reaction is determined by:

values of kinetic energy greater than activation energy

appropriate collision geometry

Factors that influence the rate of reaction

temperature

increasing temperature increases average kinetic energy of particles

DIAGRAM HERE → Maxwell curve

area under both curves is the same → same number of particles

at higher temperature, more particles have higher kinetic energies so the peak of the curve shifts rightwards

as temperature increases, collision frequency increases due to higher kinetic energy → more collisions involving particles with necessary activation energy

therefore, more successful collisions (every +10K, reaction rate doubles)

concentration

increasing concentration increases frequency of collisions between reactants → more successful collisions

as reactants are used up, the concentration decreases and the rate of reaction decreases

pressure

increasing pressure “compresses” the gas, effectively increasing concentration

surface area

increasing surface area allows for more contact and a higher probability of collisions

instead of one big chunk, divide it into smaller sections to increase total surface area

stirring can increase total surface area by ensuring individual particles are spread

catalyst → a substance that increases rate of reaction without itself undergoing chemical change

most catalysts work by providing an alternative route for the reaction that has lower activation energy

DIAGRAM HERE → uncatalyzed reaction, catalyzed reaction

without increasing temperature, more particles will have Ek>Ea, so will be able to undergo successful collisions

catalysts equally reduce Ea for both forward and reverse reactions, so does not shift equilibrium or yield

DIAGRAM HERE → Maxwell curve

catalysts increase efficiency, and there are “best” catalysts for certain reactions → otherwise reactions move too slowly or are conducted at too high temperatures

Catalysts

every biological reaction is controlled by a catalyst → enzyme

there is a specific enzyme for every particular biochemical reaction

biotechnology → field that searches for possible applications of certain enzymes

catalysts can replace stoichometric reagants → greatly enhances selectivity of processes

therefore, important aspect of Green Chemistry

catalysts are effective in small quantities and can frequently be reused

therefore do not contribute to chemical waste → increases atom economy

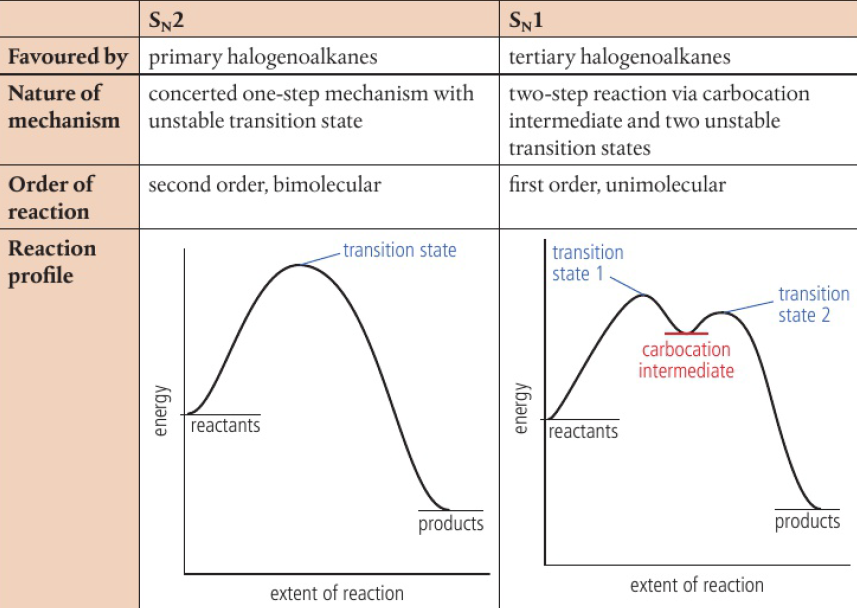

Reaction mechanisms

most reactions that occur at a measurable rate occur as a series of simple steps, each involving a small number of particles

this sequence of steps is known as the reaction mechanism

the individual steps (elementary steps) usually cannot be observed directly

therefore this is only a theory → cannot be proved (but there are clues)

often the products of a single step in the mechanism are used in a subsequent step

exists only as reaction intermediates, not as final products

ex: NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g)

mechanism follows these elementary steps:

NO2(g) + NO2(g) → NO(g) + NO3(g)

NO3(g) + CO(g) → NO2(g) + CO2(g)

overall reaction: NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g)

reactants and products cancel out → reaction intermediates

NO2 in reactants in step 1 and products in step 2 cancel out

NO3 in products in step 1 and reactants in step 2 cancel out

molecularity → used in reference to an elementary step to indicate number of reactant species involved

unimolecular → elementary step that involves a single reactant particle

bimolecular → elementary step with two reactant particles

trimolecular reactions are rare → extremely low probability of >2 particles colliding at same time with sufficient energy and correct orientation

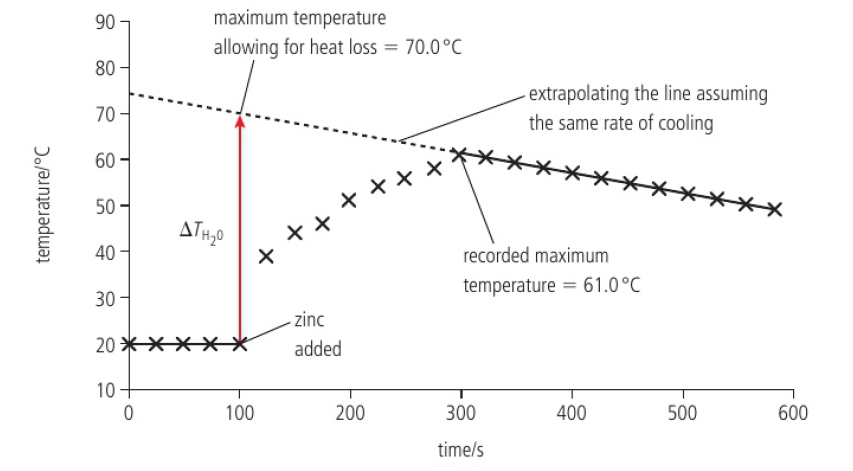

Rate-determining step

the rate-determining step is the slowest step in the reaction mechanism

products of the reaction can only appear as fast as the products of this slowest elementary step

rate-determining step therefore determines overall rate of reaction

DIAGRAM HERE → reaction coordinate, potential energy

two maxima represent the transition states

minimum represents the intermediate species

in this example, first maxima (first step) is higher, so more activation energy required → thus slowest step, so rate-determining

catalysts usually find an alternative for the slowest step to speed up the reaction (rate-determining step made faster or changes)

Rate equations

rate equations are determined experimentally and depend on the mechanism of a reaction

consider the reaction: C60O3 → C60O + O2

we can follow the reaction by recording the change in absorbance of light of a certain wavelength

absorbance is directly proportional to concentration of C60O3

rate of reaction is equal to the rate of change in concentration of C60O3

rate=- [C60O3]/t (negative because concentration is decreasing)

rate can be calculated by finding gradient of line’s tangent at a specific point

rate slows down as concentration of C60O3 decreases

similarities in concentration VS time and rate VS time graphs suggests that the rate must be related ot concentration at each time

straight-line graph between absorbance and rate confirms that the rate of reaction is directly proportional to concentration of C60O3

reaction rate is directly proportional, so reaction rate = k[C60O3]

k is the rate constant

this equation is a rate equation → first order rate equation because the concentration of the only reactant is raised to the first power

rate of all reactions can similarly be shown to depend on concentration of one or more of the reactants, and the particular relationship depends on the reaction

generally, rate is proportional to products of concentrations of reactants, each raised to a power

A+B → products so rate=k[A]m[B]n

m and n are known as the orders of the reaction with respect to A and B

overall reaction order is sum of individual orders (m+n)

orders can only be determined by experiment (empirically)

no connection between reaction equation (coefficients, moles) and rate equation

Rate equation and reaction mechanism

as the rate of reaction depends on the rate-determining step, the rate equation for the overall reaction must depend on the rate equation for the rate-determining step

because the rate-determining step is an elementary step, its rate equation comes directly from its molecularity:

A → products: unimolecular, so rate=k[A]

2A → products: bimolecular, so rate=k[A]²

A+B → products: bimolecular, so rate=k[A][B]

rate equation for rate-determining step, predictable from its reaction equation, leads to the rate equation for the overall reaction

when rate-determining step is not the first step, the intermediate cannot be used in the rate equation → instead, substitute

order of reaction with respect to each reactant is not linked to coefficients in overall equation, but is instead determined by their coefficients in the equation for the rate-determining step

Order of a reaction

reaction that is zero-order with respect to a particular reactant → the reactant is required for reaction but does not affect rate as it is not present in the rate-determining step

if a reactant is present in the rate-equation, it partakes in the rate-determining step

reaction order can be fractional or negative in more complex reactions

concentration-time graphs do not give a clear distinction between first and second order

rate-concentration graphs clearly reveal the difference

zero-order: rate=k[A]0=k

DIAGRAM HERE

concentration-time → straight line, constant rate

gradient of line = k

rate-concentration → horizontal line

first-order: rate=k[A]

DIAGRAM HERE

concentration-time → rate decreases with concentration

rate-concentration → straight line passing through origin with gradient k

second-order: rate=k[A]²

DIAGRAM HERE

concentration-time → curve, steeper at start than first-order graph but leveling off more quickly

rate-concentration → parabola (square function), gradient proportional to concentration and initially zero

order of reaction can only be determined experimentally, thus these graphs are required to distinguish them

Determination of the overall order of a reaction

methods for determining order of reaction depends on the reactants

two methods, but only initial rate method is covered

initial rates method

carrying out a number of separate experiments with different starting concentrations of reactant A, and measuring the initial rate of each reaction

concentration of other reactants are held constant to see effect of A on reaction rate

changing concentration of A but no effect on rate → zero order with respect to A

changing concentration of A produces directly proportional changes in rate of reaction → first order with respect to A (doubling concentration of A doubles reaction rate)

changing concentration of A leads to the square of that change in the rate → second order with respect to A (doubling concentration of A leads to a four-fold increase in reaction rate)

use of the integrated form of the rate equation

calculus is used to analyze the integral of rate equation

direct graphical analysis of functions of concentration against time

The rate constant, k

units of k vary with order of reaction

zero order: rate=k, k=moldm³/s

first order: rate=k[A], k=rate/concentration=s-1

second order: rate=k[A]², k=dm³/mols

third order: rate=k[A]³, k=dm6/mol²s

k is temperature dependent → general measure of rate of a reaction at a particular temperature

temperature dependence of k depends on value of activation energy

high Ea → temperature rise causes significant increase in particles that can react

low Ea → same temperature rise will have proportionally smaller effect on reaction rate

temperature dependence of k is expressed in the Arrhenius equation

The Arrhenius equation

Suante Arrhenius showed that the function of molecules with energy greater than the activation energy at temperature T is proportional to e-Ea/RT (R is gas constant)

reaction rate and therefore rate constant are also proportional to this value

k=Ae-Ea/RT

A → Arrhenius factor (frequency factor, pre-exponential factor)

A takes into account the frequency of successful collisions based on collision geometry

A is a constant for a reaction and has same units as k (so varies with order)

Arrhenius plot → lnk=-Ea/RT + lnA

rule of thumb → 10K increase doubles reaction rate

2.3: How far? The extent of chemical change

Dynamic equilibrium

reaction takes place at same rate as its reverse reaction, so no net change is observed

physical systems (ex: bromine in a sealed container at room temperature)

bromine is a volatile liquid (boiling point close to room temperature)

significant amount of Br2 molecules will have enough energy to leave the liquid state (evaporate)

container is sealed so bromine vapour cannot escape → concentration increases

some vapour molecules will collide with surface of liquid, lose energy, and become liquid

Br2(l) ⇌ Br2(g)

rate of condensation increases with concentration of vapour (more vapour particles)

eventually, rate of condensation will equal rate of evaporation

no net change → equilibrium (only occurs in a closed system)

DIAGRAM HERE → rate of condensation = rate of evaporation

chemical systems (ex: dissociation between hydrogen iodide (HI) and its elements (H2, I2)

2HI(g) ⇌ H2(g) + I2(g)

colourless gas ⇌ colourless gas + purple gas

there will be an increase in purple hue when the reaction starts (production of I2)

at some point, the increase in colour will stop

rate of dissociation of HI is fastest at the start as the concentration of HI is the greatest, then falls as the reaction proceeds

reverse reaction had initially zero rate (no H2 or I2 present) then starts slowly and increases in rate as concentrations of H2 and I2 increase

eventually, the rate of the forward and reverse reactions will equal, so concentrations remain constant

equilibrium → dynamic because both reactions are still occuring

if the contents of the flask were analyzed at this point, HI, I2, and H2 would all be present with constant concentrations → equilibrium mixture

DIAGRAM HERE → equilibrium

if the experiment were reversed (starts with H2 and I2), eventually an equilibrium mixture will again be reached

reactants ⇌ products

→ forward, ← backward

constant concentrations of products and reactants does not mean equal amounts

equilibrium position → proportion of reactant and product in equilibrium

predominantly products → lie to the right

predominantly reactants → lie to the left

Equilibrium Law

consider the reaction: H2(g) + I2(g) ⇌ 2HI(g)

if we were to carry out a series of experiments on this reaction with different starting concentrations of H2, I2, and HI, we could wait until each reaction reached equilibrium and then measure the composition of each equilibrium mixture

there is a predictable relationship among the different compositions of these equilibrium mixtures

[HI]²/[H2][I2] → concentration at equilibrium ([HI] is squared because that is its coefficient in the equation)

K → constant value, equilibrium constant (fixed value at specified temperature)

every reaction has its particular value of K

equilibrium constant expression for reaction: aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

K = [C]eqmc[D]eqmd / [A]eqma[B]eqmb

[A] → concentration, a → coefficient in reaction equation, products → numerator, reactants → denominator

high value of K → at equilibrium, proportionally more products than reactants

lies to the right, reaction almost to completion

K values tells differing extents of reactions

higher value = reaction has taken place more fully

K » 1: reaction almost goes to completion (right)

K « 1: reaction hardly proceeds (left)

Le Chatelier’s principle

a system at equilibrium when subjected to a change will respond in such a way as to minimize the effect of the change

whatever done to a system at equilibrium, it will respond in the opposite way

after a while, a new equilibrium will be established with different composition

changes in concentration

equilibrium mixture disrupted by increase in concentration of a reactant:

rate of forward reaction increases: forward =/ backward anymore

equilibrium will have shifted in favour of products (rightward)

value of K remains unchanged

same happens with decrease in concentration of product

rate of backward reaction decreases → new equilibrium position will be achieved (rightward)

often in industrial processes, product will be removed as it forms

ensures equilibrium is continuously pulled rightward → increasing yield of product

changes in pressure

equilibria involving gases will be affected if there is a change in the number of molecules

there is a direct relationship between pressure exerted by gas and the number of gas particles

increase in pressure → system response: decrease pressure by favouring the side with less molecules

new equilibrium position, K remains unchanged (if temperature does not change)

ex: CO(g) + 2H2(g) ⇌ CH3OH(g)

increase in pressure shifts equilibrium rightward → in favour of smaller number of molecules

increase in pressure → increases yield of CH3OH

if number of molecules are the same for both sides, pressure will not change equilibrium

changes in temperature

K is temperature dependent → changing temperature affects K

ex: 2NO2(g) ⇌ N2O4(g) ΔH=-57kJ/mol (forward reaction exothermic)

decrease in temperature → system produces heat → favours forward exothermic reaction

new equilibrium mixture (rightward) → K increases (higher yield at lower temperature)

increasing yield takes too long→ decreasing temperature lowers rates of reactions

addition of a catalyst

catalyst speeds up rate of reaction by providing alternative reaction pathway with a transition state with a lower activation energy

increases number of particles that have sufficient energy to react (without increasing temperature)

because both forward and backward reactions pass through the same transition state, both rates will increase → no change in equilibrium position and K

will not increase equilibrium yield of a product

speeds up attainment of equilibrium state → products form more quickly

has no effect in equilibrium concentrations → not chemically changed

The reaction quotient, Q

K is calculated using concentrations at equilibrium

Q → calculated using concentrations when not at equilibrium

as time passes and reaction proceeds, concentrations will change and eventually reach equilibrium

Q changes in direction of K → used to predict direction of reaction

if Q=K, reaction at equilibrium, no net reaction occurs

if Q<K, reaction proceeds rightward in favour of products

if Q>K, reaction proceeds leftward in favour of reactants

Quantifying the composition at equilibrium

done by calculating equilibrium constant (K) or concentration of reactants/products

only homogeneous equilibria → all reactants/products in the same phase (gas or solution)

equilibrium law can be used to solve for K and initial/final concentrations

Measuring the position of equilibrium

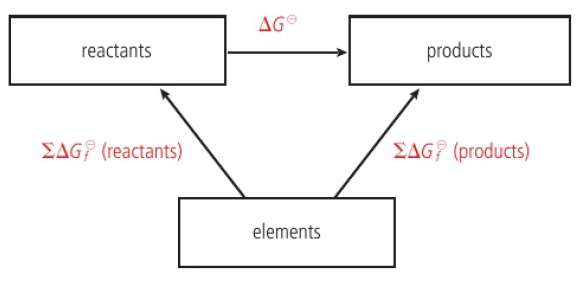

Gibbs energy change can be used to measure the position of equilibrium

ΔG → measure of work available from a system calculated for a particular composition of reactants and products (ΔG=Gproducts-Greactants)

ΔG=negative → reaction proceeds in forward direction

ΔG=positive → reaction proceeds in backward direction

ΔG=0 → reaction is at equilibrium (Gproducts=Greactants)

at the start of a reaction, total Gibbs energy of reactants is greater than products (lot of work is available) → ΔG=negative, reaction proceeds in forward direction

as reaction proceeds, total GIbbs energy of reactants decreases but of products increase

ΔG less negative, less work is available

system reaches equilibrium when total Gibbs energy of reactants and products are equal

no work can be extracted from system (ex: dead battery)

total Gibbs energy decreases as reaction progresses as work is done by the system

occurs both when reaction starts with reactants and products

equilibrium state → net reaction stops → minimum value of Gibbs energy

DIAGRAM HERE → equilibrium

DIAGRAM HERE → equilibrium

decrease in total Gibbs energy appears as work done or increase in entropy

system has highest possible value of entropy when Gibbs energy at minimum (at equilibrium)

reaction with large and negative ΔG value → spontaneous, equilibrium with high products

reaction with large and positive ΔG value → non-spontaneous, predominantly reactants

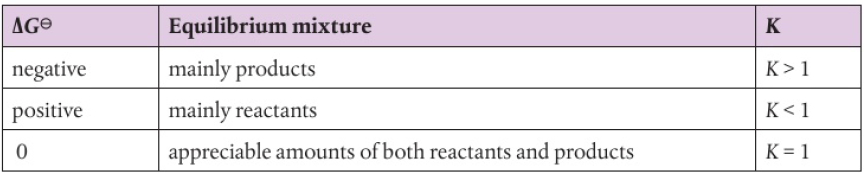

ΔG=-RT*lnk

ΔG negative, lnK positive, K>1: equilibrium mainly products

ΔG positive, lnK negative, K<1: equilibrium mainly reactants

ΔG=0, lnK=0, K=1: appreciable amounts of both reactants and products

Rate of reaction and equilibrium

ex: reaction that occurs in a single step

A + B ⇌ C + D

rate of forward reaction: k[A][B]

rate of backward reaction: k’[C][D]

K=[C][D]/[A][B] (equilibrium constant)

at equilibrium, rate of forward reaction = rate of backward reaction

k[A][B]=k’[C][D]

rearranging gives: K=k/k’

if k»k’, K is large → reaction proceeds to completion

if k«k’. K is small → reaction barely takes place

increasing concentration of reactants speeds up forward reaction (vice versa)

shifts equilibrium rightward

equilibrium constant stays the same regardless

adding a catalyst increases k and k’ by same factor → K stays the same

k=Ae-Ea/RT → activation energies of forward and backward reactions are different

differently affected by temperature

for endothermic reactions (Ea(forward) > Ea(backward)), increasing temperature will have greater effect increasing k than k’, so K increases

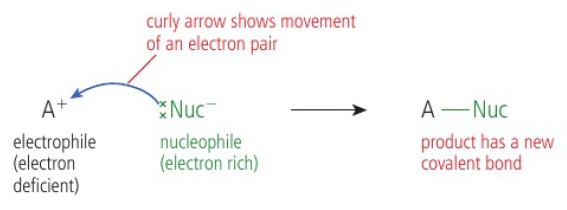

3.1: Proton transfer reactions

H+ is equivalent to a proton

proton is transferred when:

reactant loses H+ so loses positive charge

product gains H+ so gains positive charge

this type of reaction can only occur between certain species: reactants that can release H+ and products with a lone pair that can accomodate an additional H+

Bronsted-Lowry acid-base behavior

Bronsted-Lowry acids and bases

acids donate H+, bases accept H+

Bronsted-Lowry acid is a proton (H+) donor

Bronsted-Lowry base is a proton (H+) acceptor

act of donating cannot act in isolation, must always have an acceptor

an acid can only be a proton donor if a base is present to accept it

ex: HA + B ⇌ A- + BH+

HA acts as an acid, donating a proton to B → B acts like a base, accepting it

in reverse reaction, BH+ is the acid while A- acts as a base

acid HA has reacted to form base A- and base B reacted to form acid BH+

HA and A-, B and BH+ → conjugate acid-base pairs

conjugate acid-base pairs differ by one proton

acid always has one more proton than its conjugate base (H+)

ex: H3O+ → H2O, NH3 → NH2-

most polyatomic ions can form Bronsted-Lowry acids by accepting H+ (ex: OH-, NO3-)

ammonium (NH4+) cannot accept H+ to form an acid, instead loses H+

acts as a Bronsted-Lowry acid and forms its conjugate base

Bronsted-Lowry bases are defined as any species which can accept a proton

a small group of Bronsted-Lowry bases (alkalis) are soluble bases which dissolve in water to release the hydroxide ion (OH-)

Amphiprotic species

some species can act as both Bronsted-Lowry acids and bases (ex: water)

these species are amphiprotic

depends on what the species is reacting with

amphiprotic substances must possess both a lone pair of electrons (to accept H+) and hydrogen that can be released as H+ (to dissociate)

moving left to right across a period: basic metal oxides through amphiprotic oxides to acidic oxides

ex: period 3

Na2O, MgO → basic

Al2O3 → amphoteric

SiO2, P4O10, SO2, Cl2O → acidic

The pH scale

measure of acid strength based off its H+ concentration

pH = log10[H+] or [H+] = 10-pH

ex: a solution with [H+] = 0.1mol/dm³ → 10-1mol/dm³ → -(-1)pH=1pH

most common acids and bases will have a positive pH in the range 0-14

pH has no units and is inversely related to [H+]

DIAGRAM HERE

for each increase of 10 times in [H+]. pH will decrease by 1 unit

pH is measured by estimating using universal indicator paper or solution

substance tested will give a characteristic colour → compared to indicator’s colour chart

pH is measured using a pH meter that directly reads the H+ concentration using a special electrode

must be calibrated before use (pH is temperature-dependent)

Ionization of water

majority of acid-base reactions involve ionization in aqueous solution

water does ionize, only very slightly at normal temperatures and pressures

H2O(l) ⇌ H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

K=[H+][OH-]/[H2O] → concentration of water is considered constant as so little of it ionizes

Kw=[H+][OH-] → ionic product constant of water

at 298K, Kw=1×10-14

H+ in aqueous solution always exists in H3O+(aq)

in pure water, [H+]=[OH-], so [H+]=√Kw

[H+]=1×10-7, pH=7 → neutral

[H+] x [OH-] is constant, so they have an inverse relationship

when one increases, the other decreases

acidic: [H+]>[OH-], pH<7

neutral: [H+]=[OH-], pH=7

alkaline: [H+]<[OH-], pH>7

Kw is an equilibrium constant → temperature dependent

increasing temperature shifts equilibrium rightward → increases Kw

[H+] and [OH-] increase → pH decreases

decreasing temperature shifts equilibrium leftward → decreases Kw

[H+] and [OH-] decrease → pH increases

pH of water is 7.00 only at 298K

still neutral regardless of temperature because [H+]=[OH-]

Strong and weak acids and bases

Bronsted-Lowry acids and bases dissociate in solution

acids produce H+ ions and bases produce OH- ions

aqueous solutions exist as equilibrium mixtures containing both undissociated form and its ions

ex: HA(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ A-(aq) + H3O+(aq)

if this acid dissociates fully, its equilibrium is positioned at the right → exists virtually entirely of ions

this is said to be a strong acid

if the acid dissociates only partially, equilibrium lies to the left → undissociated form dominates

this is said to be a weak acid

ex: HCl(aq) + H2O(l) → H3O+(aq) + Cl-(aq)

strong acid + base → conjugate acid + conjugate base

strong acids are good proton donors

because their dissociation reaction goes almost to completion, their conjugate bases do not readily accept protons

in this example, the strong acid HCl reacts to form conjugate base Cl- which shows no basic properties

weak acids are poor proton donors

conjugate bases readily accept protons

acid dissociation reactions favour the production of the weaker conjugate

ex: NaOH(aq) → Na+(aq) + OH-(aq)

NaOH is a strong base because it ionizes fully

strong bases are good proton acceptors → react to form conjugates that show no acidic properties

base ionization reactions favour the production of the weaker conjugate

strength of an acid or base is a measure of how readily it dissociates in aqueous solution

TABLE HERE → common strong and weak acids and bases

since strength of an acid depends on the ease with which it dissociates to release H+ ions, it thus depends on the strength of the bond that has to be broken to release H+

longer bond = weaker bond = stronger acid

thus acid strength of hydrogen halides increase down the group (HF<HCl<HBr<HI)

distinguishing strong/weak acids/bases → strong acids/bases will contain a higher concentration of ions

comparisons only work when solutions of the same concenration are compared at the same temperature

electrical conductivity

depends on concentration of mobile ions (solution)

strong acids/bases will show higher conductivity

tested using a conductivity meter, probe, or pH meter with conductivity setting

rate of reaction

stronger acids would have an increased rate

pH

the stroner the acid, the lower the pH value

measured using universal indicator or pH meter

Neutralization reactions

reaction between an acid and base (H+ + OH- → H2O) is a neutralization reaction

during the reaction, an ionic compound (salt) forms → hydrogen in acid is replaced by a metal/positive ion

parent acid, parent base → relationship between an acid, a base, and their salt

when acids react with reactive metals, a salt is also formed (metal ion replaces hydrogen)

no H+ transfer, hydrogen reduced as gas (H2)

hydrogen ions are becoming electrically neutral by accepting electrons

metal is being ionized by electron loss

ex: Mg(s) + 2HCl(aq) → MgCl2(aq) + H2(g)

Mg(s) → Mg2+(aq) + 2e- (electron loss → oxidation)

2H+(aq) + 2e- → H2(g) (electron gain → reduction)

redox reactions, cannot be described by Bronsted-Lowry acid-base theory

acid + base → salt + water

metal oxides/hydroxides are bases which react with acids to produce a salt and water

ex: HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l)

ammonia solution is also a soluble base which reacts with acids to form a salt and water

ex: HNO3(aq) + NH4OH(aq) → NH4NO3(aq) + H2O(l)

when choosing a base in solution to make a specific salt, use solubility rules:

only soluble carbonates/hydrogencarbonates are: NH4CO3, Na2CO3, K2CO3, KHCO3, Ca(HCO3)2

only soluble hydroxides are: NH4OH, LiOH, NaOH, KOH

acid + carbonate → salt + water + carbon dioxide

metal carbonates/hydrogencarbonates react with acids to produce a salt, water, and carbon dioxide

ex: 2HCl(aq) + CaCO3(aq) → CaCl2(aq) + H2O(l) + CO2(g)

2H+(aq) + CO32-(aq) → H2O(l) + CO2(g)

H+(aq) + HCO3-(aq) → H2O(l) + CO2(g)

gas is given off, visibly produces bubbles → effervescence

neutralization reactions are exothermic

net reaction is formation of H2O from its ions (H+(aq) + OH-(aq) → H2O(l))

other ions (spectator ions) do not change during reaction → can be cancelled out

for reactions between strong acids/bases, enthalpy of neutralization → H=-57kJ/mol

expressed per mole of H2O formed → overall reaction is formation of water

pH curves

following examples all use (for better comparison):

0.10 mol/dm³ solutions for all acids and bases

initial volume of 50cm³ of acid in conical flask, base added with burette

monoprotic acids and bases → reacts in 1:1 ratio, equivalence is achieved at equal volumes for these equimolar solutions (i.e. when 50cm³ of base has been added to 50cm³ of acid)

acid-base titration → controlled volumes of one reactant are added gradually from a burette to a fixed volume of the other reactant that has been measured using a pipette and placed in a conical flask

reaction between acid and base takes place in flask until the equivalence/stoichometric point is reached

until they exactly neutralize each other

pH meter or indicator is used to detect the exact point equivalence is reached

when a base is added to an acid in a neutralization reaction, there is a change in pH

change is not linear (mostly due to logarithmic nature of pH) → shown on pH curve

in most titrations, a big jump in pH occurs at equivalence (point of inflection)

at equivalence, acid and base exactly neutralized each other → solution is only salt and water

ex: HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) (strong acid + strong base)

full dissocation is assumed → both acid and base are strong

when base is added, volume also increases → changing concentration, changing pH

DIAGRAM HERE

initial pH=1 → pH of strong acid

pH changes only gradually until equivalence

very sharp jump in pH at equivalence (3→11)

after equivalence, flattens out at a high value → pH of strong base

pH at equivalence (pH=7)

measured by continuously using a pH probe

weak acid + strong base

DIAGRAM HERE

initial pH fairly high (pH of weak acid)

pH stays relatively constant until equivalence → buffer region

jump in pH at equivalence (not as much of a jump as strong acid)

after equivalence, curve flattens out at high pH (pH of strong base)

pH at equivalence > 7

anion hydrolysis releases OH-

point where 25/50cm³ of base is added → half-equivalence point (half of the acid has been neutralized)

mixture has equal quantities of a weak acid and its salt → buffer solution

buffer region → pH is relatively resistant to change

at this point, pH=pKa because [acid]eqm=[HA]initial so [salt]eqm=[A-]eqm

strong acid + weak base

DIAGRAM HERE

initial pH=1 → strong acid’s pH

pH remains relatively constant through buffer region until equivalence

jump in pH at equivalence (pH 3-7)

curve flattens out after equivalence at fairly low pH (pH of weak base)

pH at equivalence < 7

weak acid + weak base

pH at equivalence is difficult to define

DIAGRAM HERE

initial pH is fairly high (weak acid)

addition of base causes pH to rise steadily

change in pH at equivalence is much less sharp than other titrations

after equivalence, curve flattens out at fairly low pH (weak base)

there is no defined pH at equivalence because there are several equilibria involved

The pOH scale

pH scale simplifies [H+], pOH simplifies [OH-]

OH- ions are often found in low concentrations in solutions

pOH = -log10[OH-], pH = -log10[H+]

since [H+][OH-] = Kw = 1×10-14 at 298K:

pH + pOH = 14.00 at 298K

pKw = -log10(Kw)

Kw = 10-pKw

pH + pOH = pKw

Dissociation constants

weak acids and bases do not fully dissociate → concentrations of ions in solutions cannot be deduced from initial concentrations, depends on extent of dissociation

dissociation of weak acids and bases are represented as equilibrium expressions

ex: HA(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + A-(aq) (weak acid HA dissociating in water)

K=[H3O+][A-] / [HA][H2O] → concentration of water is constant

Ka=[H3O+][A-] / [HA] → acid dissociation constant

fixed value for a particular acid at a specified temperature

the higher the value of Ka at a particular temperature, the greater the dissocation, so the stronger the acid

because Ka is an equilibrium constant, it is not dependent on the acid’s concentration or other ions

ex: B(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ BH+(aq) + OH-(aq) (weak base B dissociating in water)

Kb=[BH+][OH-] / [B] → base dissociation constant

the higher the value of Kb at a particular temperature, the greater the ionization, so the stronger the base

calculation rules involving Ka and Kb:

given concentration of an acid/base is its initial concentration → before dissociation

pH/pOH values refers to concentration of H+/OH- ions at equilibrium

concentration values for Ka/Kb must be the equilibrium values for reactants and products

when extent of dissociation / Ka and Kb value is very small, [acid]initial=[acid]equilibrium (same for base)

pKa and pKb

pKa = -log10Ka, pKb = -log10Kb → similar to pH/pOH scale

pKa and pKb numbers are usually positive and have no units

relationship between Ka/pKa and Kb/pKb is inverse

stronger acid → Ka increases, pKa decreases; stronger base → Kb increases, pKb decreases

pKa/pKb must be quoted at a specified temperature

Ka x Kb = Kw so pKa + pKb = 14.00 at 298K

the stronger the acid, the weaker its conjugate base will be

the higher the Ka, the lower the Kb for its conjugate

pH of salt solutions

salt formed in neutralization reaction is an ionic compound → cation is conjugate acid of parent base, anion is conjugate base from parent acid (MOH + HA → M+A- + H2O)

pH of a salt solution depends on whether/to what extent their ions react with water and hydrolyze it

strong acid + strong base

neither ion hydrolyses

neutral, pH=7

weak acid + strong base

anion hydrolyses

basic, pH>7

strong acid + weak base

cation hydrolyses

acidic, pH<7

weak acid + weak base

both ions hydrolyse

depends on relative strengths, pH cannot generalize

Acid-base indicators

indicators are weak acids/bases in which their undissociated and dissociated forms have different colours

only weak acids will be considered → HInd (generic acidic indicator)

HInd(aq) ⇌ H+(aq) + Ind-(aq) (different colours as HInd and Ind-)

increasing [H+] → equilibrium shifts leftward in favour of HInd

Ka=[H+][Ind-] / [HInd]

at the point where the equilibrium is balanced ([Ind-]=[HInd]), the indicator is exactly in th emiddle of its colour change: Ka=[H+][Ind-] / [HInd] = [H+] so pKa=pH

addition of a very small volume of acid/base will shift equilibrium → change colour

this point is the end point (pH=pKa(indicator))

different indicators have different pKa values so will have different end points

an indicator will be effective in signalling the equivalence point when its end point coincides with the pH at equivalence

different indicators must be used for different titrations, depending on the pH at equivalence

choosing an appropriate indicator:

determine what combination of strong/weak acids/bases are reacting together

deduce pH of salt solution at equivalence

consult data tables to choose an indicator with end point in range of equivalence point

Buffer solutions

buffer → something that acts to reduce the impact of one thing on another (shock absorber)

buffer acts to reduce the pH impact of added acid/base on a chemical system

buffer solution is resistant to changes in pH on the addition of small amounts of acid/alkali

acidic buffers (maintain pH<7)

made by mixing an aqueous solution of a weak acid with a solution of its salt of a strong alkali

ex: NaCH3COO(aq) → Na+(aq) + CH3COO-(aq) (soluble salt → fully dissociates)

mixture contains relatively high concentrations of CH3COOH and CH3COO- (acid and its conjugate base)

resovoirs, ready to react with added OH- and H+ in neutralization reactions

addition of H+ (acid): CH3COO-(aq) + H+(aq) ⇌ CH3COOH(aq)

addition of OH- (base): CH3COOH(aq) + OH-(aq) ⇌ CH3COO-(aq) + H2O(l)

basic buffers (maintain pH>7)

made by mixing an aqueous solution of a weak base with its salt of a strong base

ex: NH3(aq) and NH4Cl(aq) (weak base and salt of weak base with strong acid)

NH3(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ NH4+(aq) + OH-(aq) (equilibrium lies to the left (weak base))

NH4Cl(aq) → NH4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) (soluble salt → fully dissociates)

resovoirs → NH4+ and NH3 to be used in neutralization reactions

addition of acid (H+): NH3(aq) + H+(aq) ⇌ NH4+(aq)

addition of base (OH-): NH4+(aq) + OH-(aq) ⇌ NH3(aq) + H2O(l)

buffer solutions are a mixture containing both an acid and base of a weak conjugate pair

buffer’s acid neutralizes added alkali, buffer’s base neutralizes added acid → pH change is resisted

has to be weak because strong acids/bases dissociate fully → do not exist in equilibrium, so cannot carry out reversible reactions to respond to both added H+ and OH- ions

Buffer composition and pH

pH of a buffer solution depends on the interactions among its components

ex: generic weak acid HA and its salt MA

HA(aq) ⇌ H+(aq) + A-(aq), MA(aq) → M+(aq) + A-(aq)

the dissociation of the weak acid is so small it is considered negligible

[HA]initial = [HA]equilibrium

salt is considered to be fully dissociated into its ions

[MA]initial = [A-]equilibrium

Ka=[H+][A-] / [HA] so [H+] = Ka[HA] / [A-]

[H+] = Ka[HA]initial / [MA]initial

[H+] = Ka[acid] / [salt]

pH = pKa + log10[salt]/[acid]

pOH = pKb + log10[salt]/[base]

pH of a buffer solution can be determined from:

pKa/pKb values of its component acid/base

ratio of initial concentrations of acid/base and salt used to prepare the buffer

when [acid] = [salt], pH=pKa / pOH=pKb

Factors that can influence buffers

dilution

dilution does not change Ka/Kb or ratio of acid/base to salt concentration → does not change pH

buffering capacity → amount of acid/base absorbed without significant changes in pH

decreases when concentrations are decreased with dilution

temperature

affects Ka and Kb so affects pH of the buffer

3.2: Electron transfer reactions

Redox reactions

oxidation is the loss of electrons

reduction is the gain of electrons

oxidation is hydrogen loss and reduction is hydrogen gain

oxidation is an increase in oxidation state and reduction is a decrease in oxidation state

oxidation state for molecules with more than one atom is an average value → can be a non-integer

oxidizing agent → reactant that accepts electrons (brings about the oxidation of the other reactant)

reducing agent → reactant that supplies electrons (brings about reduction and is oxidized)

Redox titrations

similar to acid-base titrations → redox reaction between two reactants to find equivalence point and thus titre

ex: Iodine-thiosulfate solution

several different reactions use an oxidizing agent to convert excess iodine ions into idoine:

2I-(aq) + oxidizing agent → I2(aq) + other products

liberated I2 then reacts with sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3)

oxidation: 2S2O32-(aq) → S4O62-(aq) + 2e-

reduction: I2(aq) + 2e- → 2I-(aq)

2S2O32-(aq) + I2(aq) → 2I-(aq) + S4O62-(aq)

starch can be used as an indicator → deep blue in presence of I2

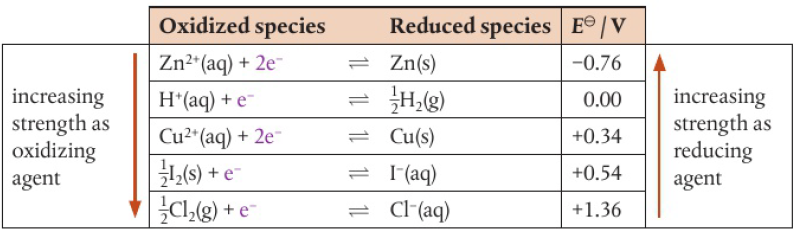

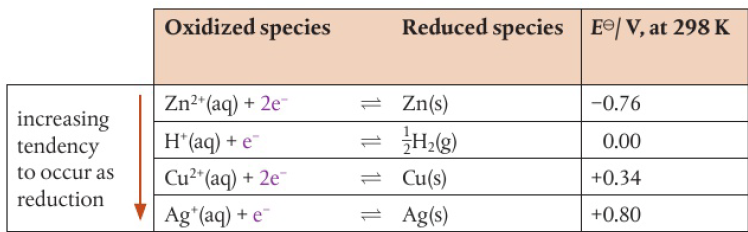

Strength of oxidizing/reducing agents

strength depends on relative tendencies to lose/gain electrons

halogens react by gaining electrons and becoming negative ions → act as oxidizing agents

tendency to gain electrons decreases down the group (F2>I2 in reactivity)

the more reactive it is, the stronger it is as an oxidizing agent

ex: Cl2(aq) + 2KI(aq) → 2KCl(aq) + I2(aq)

K+ does not change, it is a spectator ion → can be disregarded

Cl is more reactive so “wins” over K because it is a stronger oxidizing agent (displaces K)

metals have a tendency to lose electrons and form positive ions → act as reducing agents

more reactive metals are stronger reducing agents

reactivity of group 1 metals increase down the group (K>Na as a reducing agent)

can be confirmed through displacement reactions

if the metal is displaced by another, it is a weaker reducing agent

Oxidation of metals by acids

acids react with metals to form salts and release hydrogen

ex: 2HCl(aq) + Zn(s) → ZnCl2(aq) + H2(g)

removing spectator ions: 2H+(aq) + Zn(s) → Zn2+(aq) + H2(g)

zinc is oxidized (0→+2) → acts as a reducing agent

zinc has the strength to “force” the hydrogen to accept the electrons as it is a strong reducing agent

no reaction occurs when copper is added to a dilute acid

copper lacks the strength to displace hydrogen

hydrogen is less reactive than zinc but more reactive than copper

this is why acids are so corrosive (except to low reactivity metals like Ag and Au)

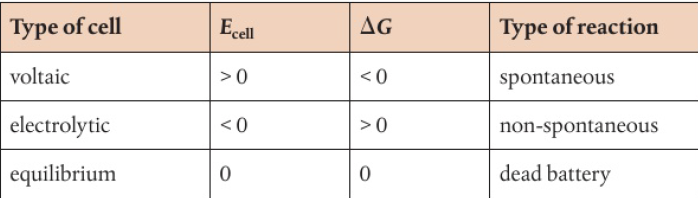

Comparing voltaic and electrolytic cells

voltaic and electrolytic cells are known as electrochemical cells

voltaic cells convert chemical energy to electrical energy

a spontaneous chemical reaction drives electrons around a circuit

electrolytic cells convert electrical energy to chemical energy

an electric current reverses the normal directions of chemical change → non-spontaneous reactions occur

oxidation occurs at the anode and reduction at the cathode for both cells

anode is the negative terminal in a voltaic cell but the positive terminal is an electrolytic cell

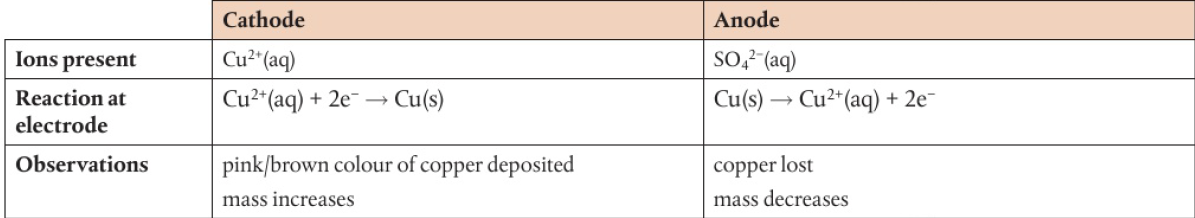

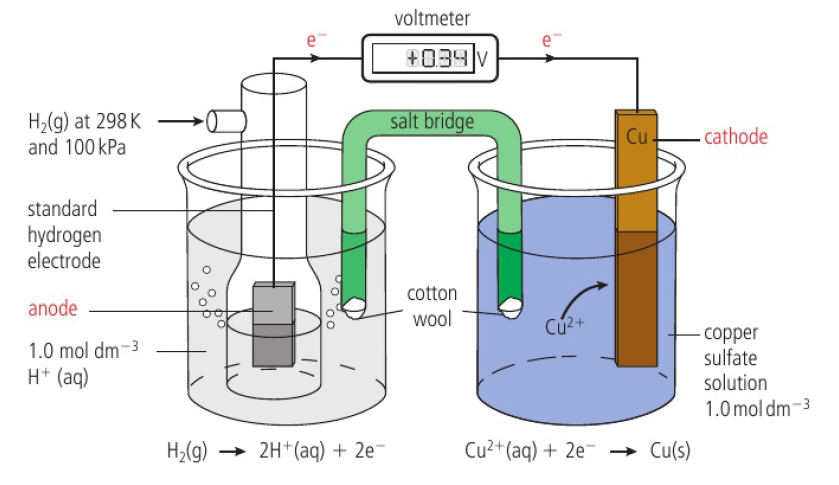

Primary voltaic cells

if the half-reactions in a redox reaction occur at spatially seperated electrodes, the electrons must pass through an external circuit

electric current is produced → voltaic/galvanic cell

chemicals are not renewed during the process → primary cell

battery normally consists of several cells connected together

ex: Zn(s) → Zn2+(aq) + 2e-, Cu2+(aq) + 2e- → Cu(s)

half-cell made by putting a strip of metal into a solution of its ions

in the zinc half-cell, zinc atoms form ions by releasing electrons

makes surface of the metal negatively charged with respect to the solution

negative charge on electrode attracts zinc ions which can gain electrons in the reverse process (Zn(s) ← Zn2+(aq) + 2e-)

at a particular charge seperation, the rates of both processes will equal and equilibrium will be reached

Zn(s) ⇌ Zn2+(aq) + 2e-

position of equilibrium depends on reactivity of metal (the more reactive, the more formation of ions → greater negative charge, more electrons)

when the two half-cells are connected, electrons will have a tendency to flow spontaneously to the less negative half-cell

tendency of electrons to flow is quantified by measuring the potential difference between 2 electrodes

anode → where oxidation occurs (zinc), cathode → where reduction occurs (copper)

cell diagram convention

phase boundary → single vertical line between a solid electrode and an aqueous solution in a half-cell

salt bridge → double vertical line

aqueous solutions of each electrode are placed next to the salt bridge

anode on left, cathode on right (electrons flow from left to right)

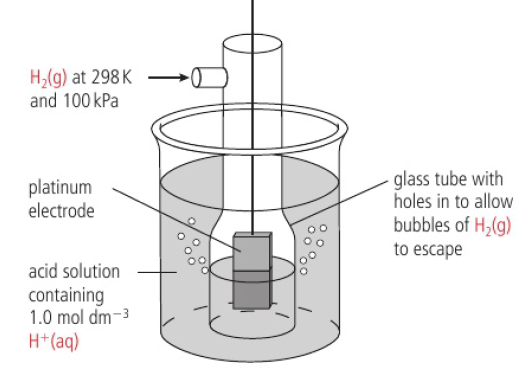

Half-cells and voltage

any two half-cells can be connected to make a voltaic cell

direction of electron flow and voltage produced will be determined by the difference in reducing strength

most cases can be judged by the relative position of the metals in the activity series

larger voltage will be produced when there is a greater difference in electrode potentials

electrons flow from more to less reactive metal (ex: Zn→Cu, Zn→Ag)

anode (where electrons are produced) to cathode (where electrons are accepted)

Secondary (rechargeable) cells

involves reversible redox reactions using electrical energy

lithium-ion battery → benefits from lithium’s low density and high reactivity

can store a lot of electrical energy per unit mass

as lithium is reactive, steps must be taken to prevent it from forming an oxide layer (decreases contact with electrolyte)

lithium cathode placed in lattice of a metal oxide (MnO2), lithium anode mixed with graphite

non-aqueous polymer-based electrolyte is used

discharging:

lithium is oxidized at the negative electrode: Li(polymer) → Li+(polymer) + e-

Li+ ion and MnO2 are reduced at the positive electrode: Li+(polymer) + MnO2(s) + e- → LiMnO2(s)

the two half reactions are reversed when the battery is recharged

fuel cells → combustion reactions are redox reactions, can be used to produce an electric current if reactants are physically seperated

hydrogen fuel cell: H2(g) + ½O2(g) → H2O(l) ΔHf = -285.8kJ/mol

Gibbs energy gives maximum energy available for electrical output

H2(g) + ½O2(g) → H2O(l) ΔG = -228.6kJ/mol

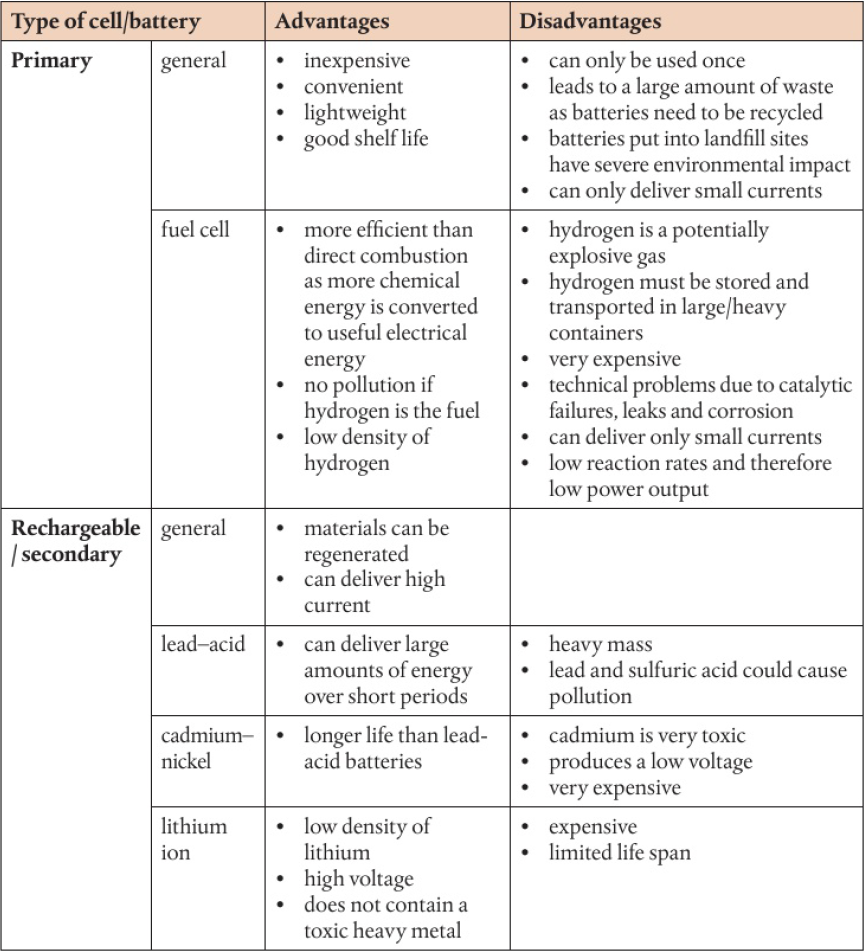

Advantages and disadvantages of fuel cells, primary cells, and secondary cells

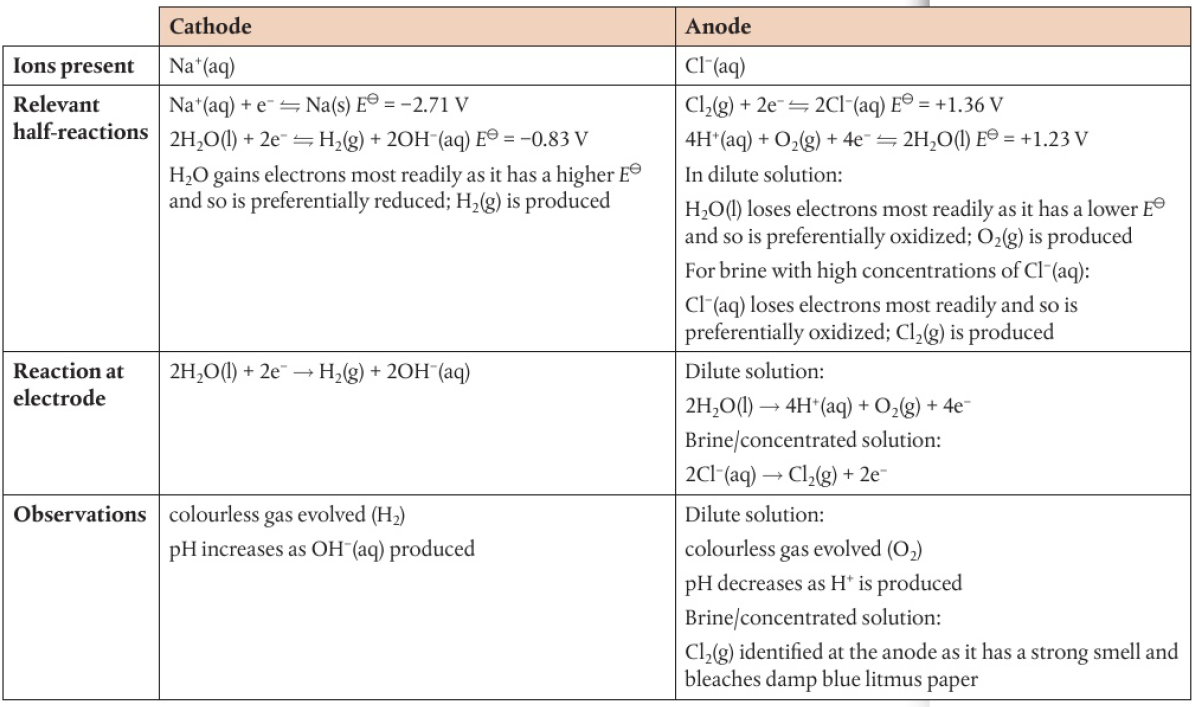

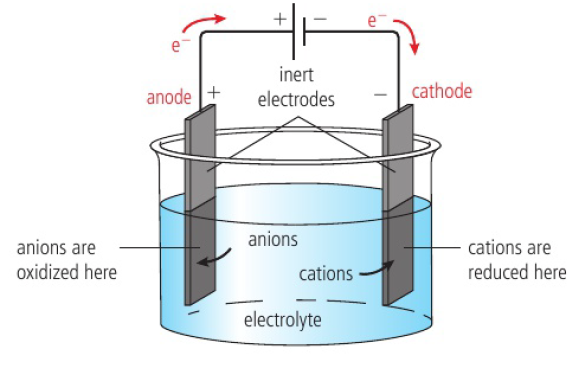

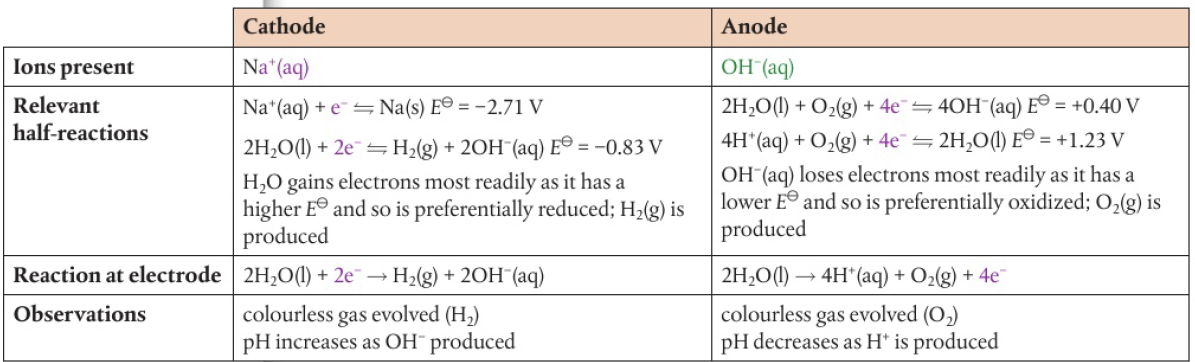

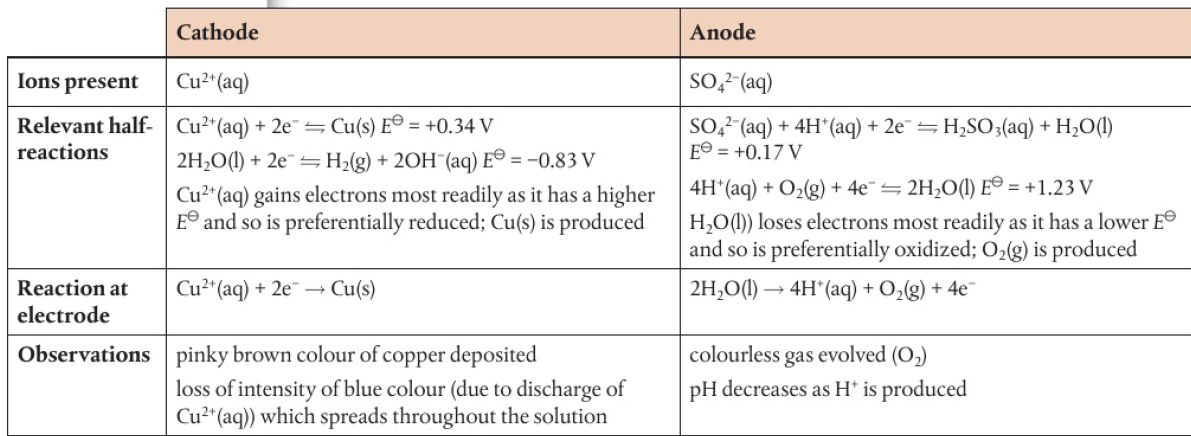

Electrolytic cells

voltaic cell takes the energy of a spontaneous redox reaction and harnesses it to generate electrical energy

electrolytic cell reverses this process using an external source of electrical energy to bring about a non-spontaneous redox reaction that would otherwise not take place

electrolysis → process where electricity is used to bring about chemical reactions which break down substances

reactant must contain mobile ions which allow the currrent to pass through the electrodes

electrolyte → liquid, usually a molten ionic compound or an aqueous solution of an ionic compound

as an electric current passes through the electrolyte, redox reactions occur at the electrodes, removing the charges on the ions and forming products that are electrically neutral

ions are discharged during this process

source of electric energy is a battery/DC power source

electrodes are placed in the electrolyte and connected to the power supply

electrodes are made from a conducting substance (metal/graphite)

electrodes are inert → do not take part in the redox reactions

electrodes must not touch each other → “shorts” the circuit, current would bypass the electrolytic cell

electric wires connect electrodes to power supply

ex: spontaneous reaction Na(s) + ½Cl2(g) → NaCl(s)

electrons are transferred from sodium to chlorine

process can be reversed if solid sodium chloride is first converted into the molten state: NaCl(s) → Na+(l) + Cl-(l)

ions are now mobile, ions can act as an electrolyte in an electrochemical cell

battery pushes electrons towards the negative electrode (cathode) → accepted by Na+ ions as they are reduced in the electrolyte

Na+(l) + e- → Na(l)

electrons are released at the positive terminal (anode) → chloride ions are oxidized

2Cl-(l) → Cl2(g) + 2e-

chemical reactions occuring at each electrode remove ions from electrolyte

compound has been split into its constituent ions → electrolysis has occured

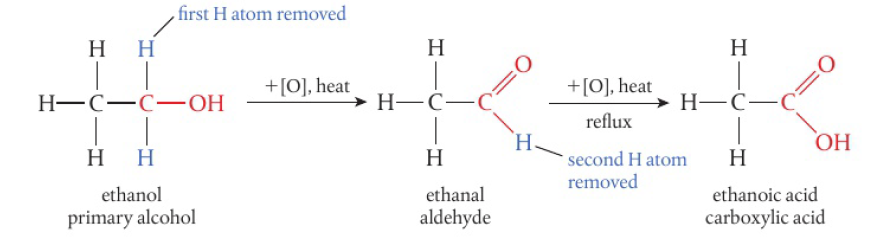

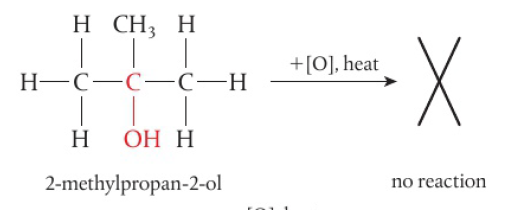

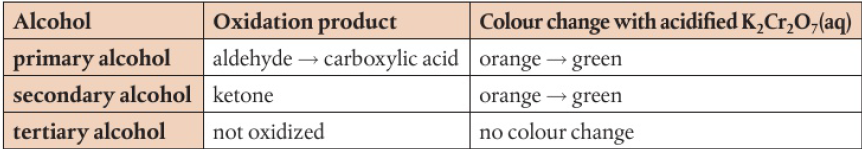

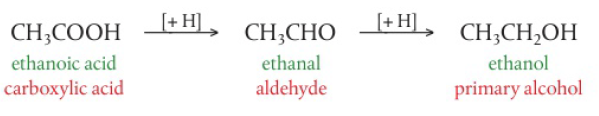

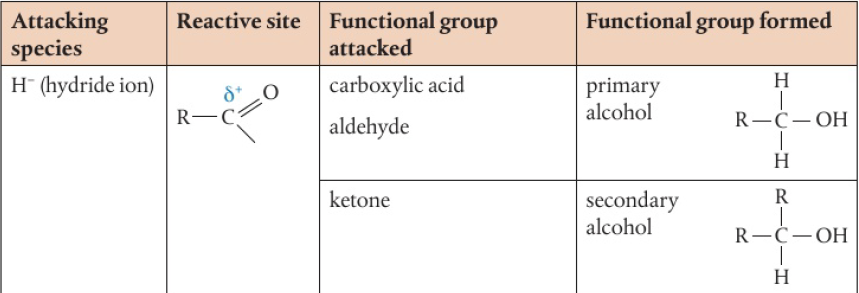

Oxidation of functional groups in organic compounds

oxidation of alcohols

commonly the laboratory process uses acidified potassium dichromate (VI) → bright orange solution, reduced to green Cr3+(aq) as alcohol is oxidized on heating

when writing equations for these reactions, it is convenient to show the oxidizing agent simply as “+[O]”

primary alcohols → 2 H atoms attached to the carbon with the hydroxyl group, can be oxidized in a two-step reaction

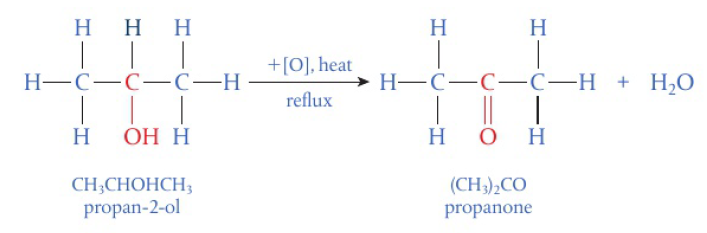

removal of the first H atom leads to the formation of the aldehyde