W9: Neonatal and Infant Abdomen Radiography - Comprehensive Notes

Malrotation of the bowel: A congenital condition where the bowel doesn't rotate correctly during development, leading to potential twisting (volvulus) or obstruction.

Volvulus: Twisting of the bowel, which can cut off blood supply. In neonates, this often refers to midgut volvulus due to malrotation.

Meconium ileus: A bowel obstruction in newborns caused by thick, sticky meconium blocking the ileum. It's strongly associated with cystic fibrosis.

Meconium plug syndrome: A milder obstruction in newborns where a plug of meconium blocks the colon. It's often associated with infants of diabetic mothers.

Meconium peritonitis: Inflammation of the peritoneum (abdominal lining) caused by meconium leaking into the abdominal cavity, usually due to a bowel perforation before birth.

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC): A serious intestinal disease primarily affecting premature infants. It involves inflammation and damage to the intestinal wall, potentially leading to perforation.

Imperforate anus: A birth defect where the anus is missing or malformed.

Esophageal atresia or fistula: Esophageal atresia is when the esophagus doesn't form a continuous passage to the stomach. A fistula is an abnormal connection; a tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) is when there is an abnormal connection between the esophagus and the trachea.

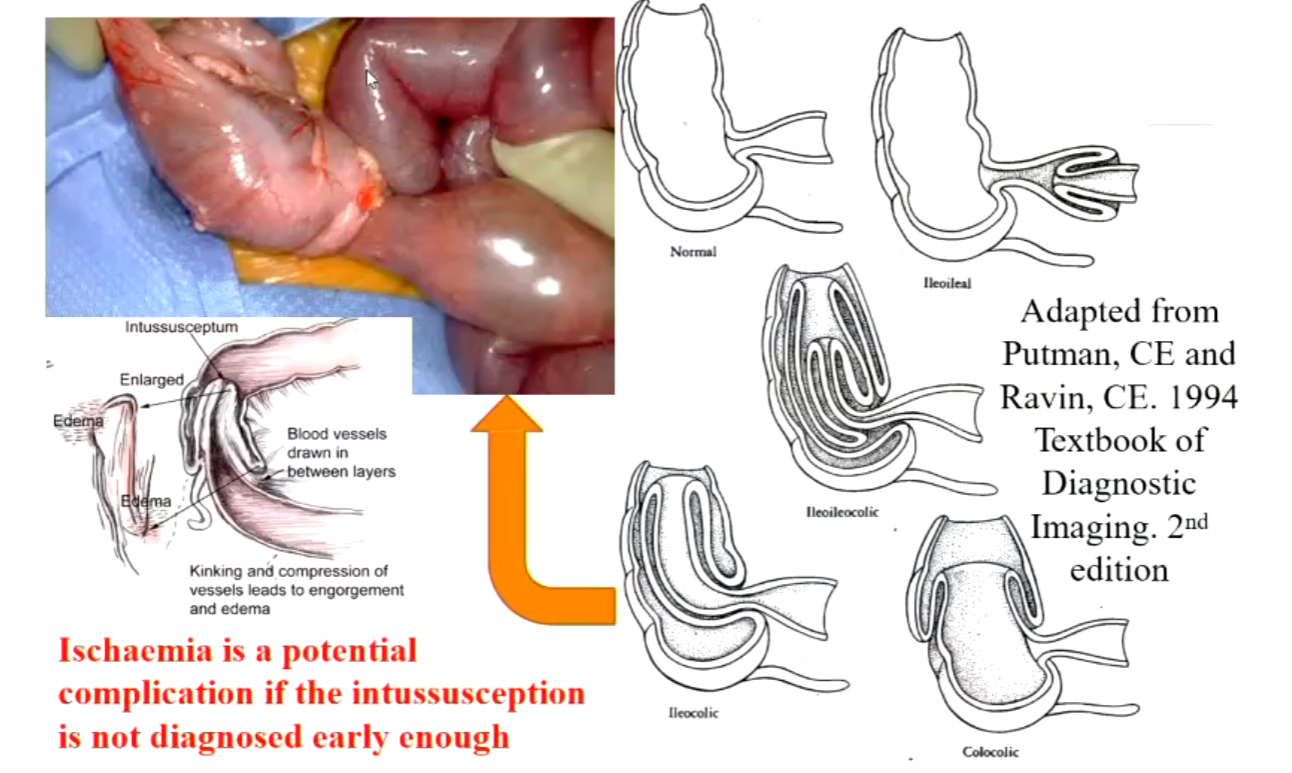

Intussusception: An INTUSSUSCEPTION is formed by the proximal bowel (Intussusceptum) which is hyperactive forcing itself into the distal bowel (Intussuscipiens) which is not hyperactive.

Perforation: A hole in the wall of a body organ.

Projections for Neonate Pathologies

Volvulus (midgut volvulus due to malrotation of the gut):

Supine

Left lateral decubitus

Ileus:

Supine

Left lateral decubitus

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC):

Initial: Supine (may include left lateral decubitus)

Progress: Supine (may include left lateral decubitus or dorsal decubitus)

Imperforate anus:

Supine

Prone lateral rectum

Perforation:

Supine

Left lateral decubitus or dorsal decubitus

Oesophageal atresia:

Supine abdomen and chest

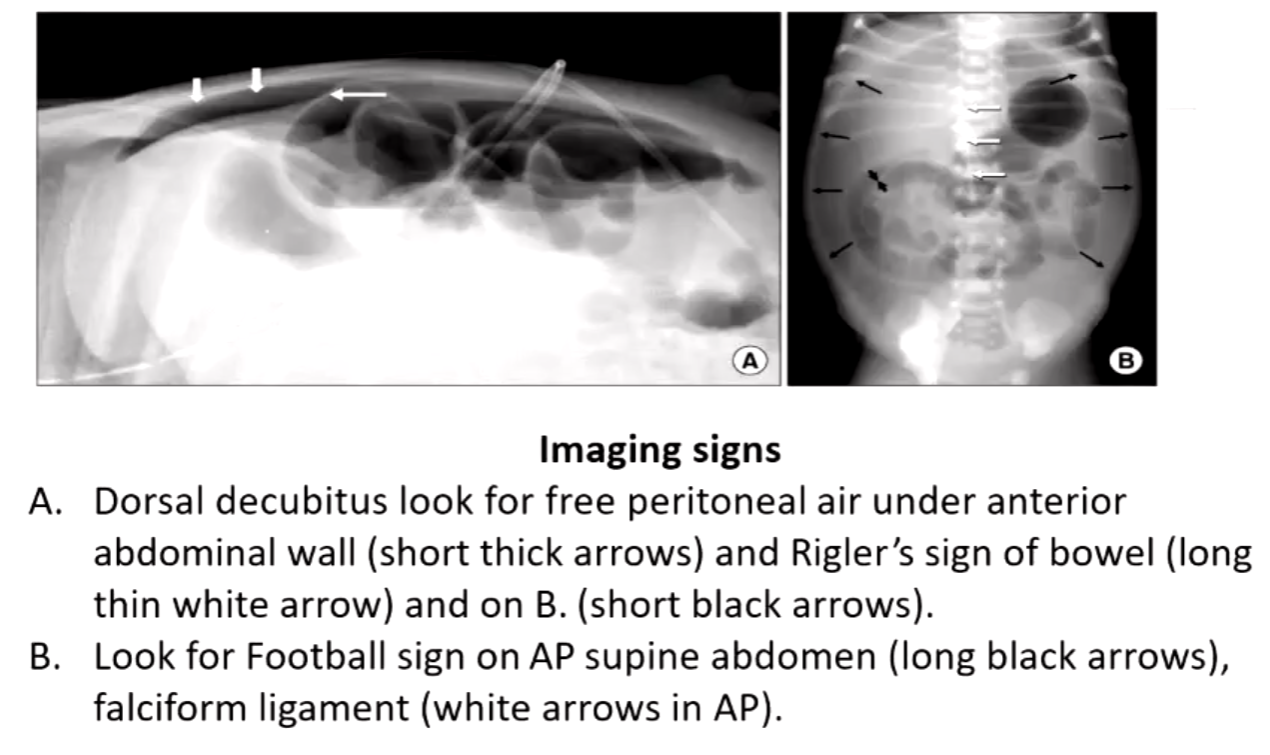

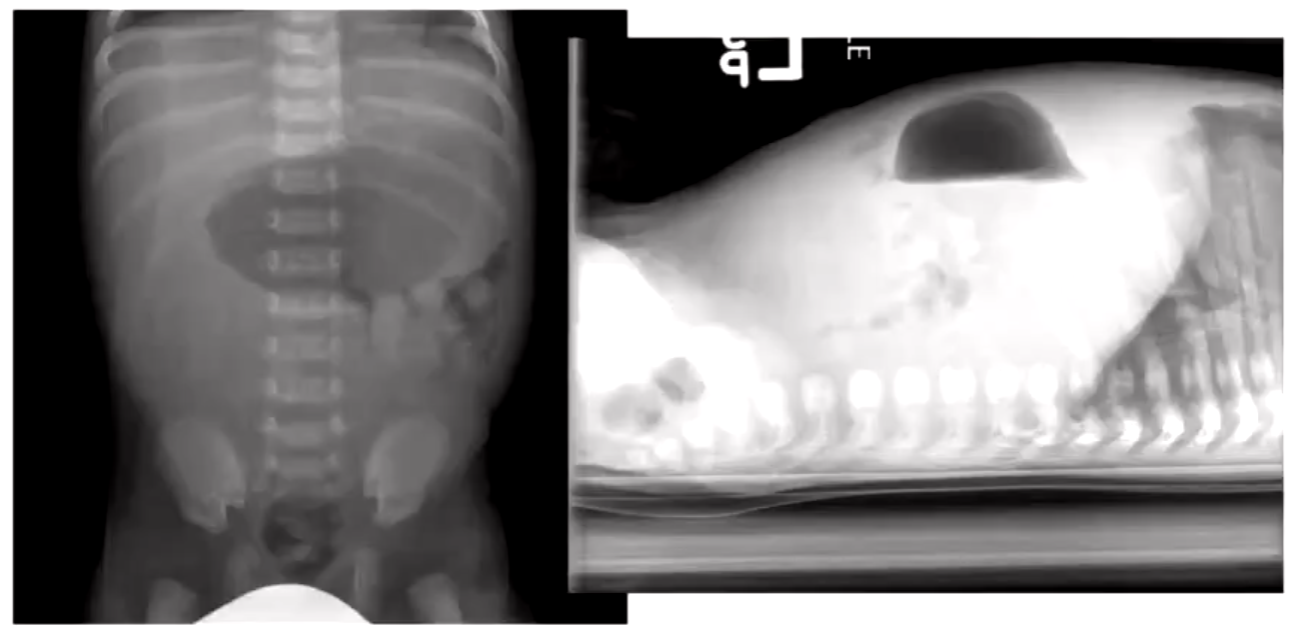

Perforation - Pneumoperitoneum Imaging Signs

Dorsal decubitus: Look for free peritoneal air under the anterior abdominal wall and Rigler’s sign of the bowel.

AP supine abdomen: Look for the Football sign and falciform ligament.

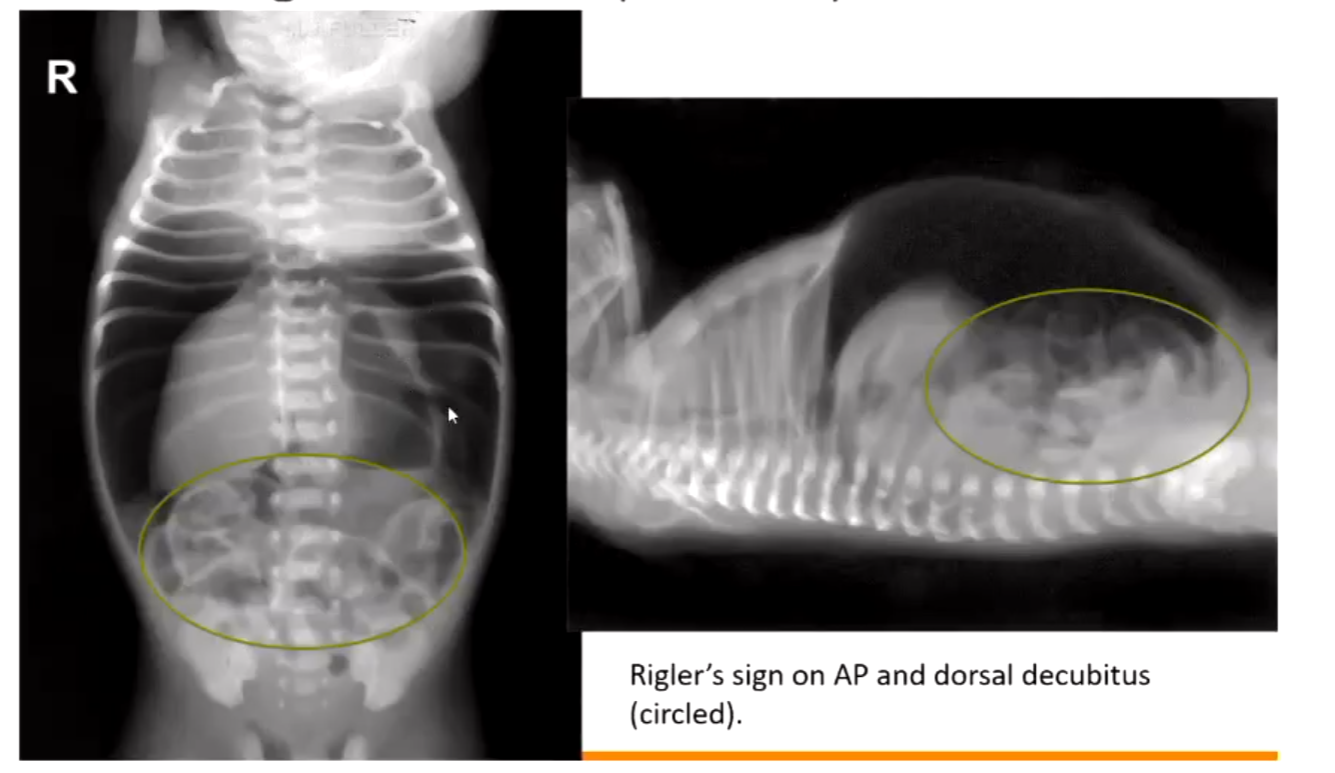

Perforation - Sign of Tension Pneumoperitoneum

Rigler's sign on AP and dorsal decubitus.

Meconium Ileus

Meconium ileus is a low small bowel obstruction due to inspissated meconium (i.e., desiccated meconium) impacted in the distal ileum.

Virtually all infants with a meconium ileus will have cystic fibrosis.

Approximately 10-15% of infants with cystic fibrosis present with a meconium ileus, due to a deficiency of pancreatic secretions resulting in the meconium becoming thick and sticky.

The radiographic appearances of a meconium ileus can be:

Dilated small bowel loops with a limited number of small bowel air-fluid levels.

Bubbly or frothy appearance of the intestinal contents, more commonly in the RLQ (Right Lower Quadrant).

The distal ileum and colon containing multiple round filling defects.

A microcolon – unused colon.

Image Examples:

Dilated terminal ileum with no significant air in the ascending colon.

Water-soluble contrast media enema demonstrating microcolon and rounded collections of inspissated meconium in the distal terminal ileum.

Inspissated (desiccated) meconium in dilated terminal ileum in pellet form.

Normal caliber caecum and ascending colon distal to the obstruction.

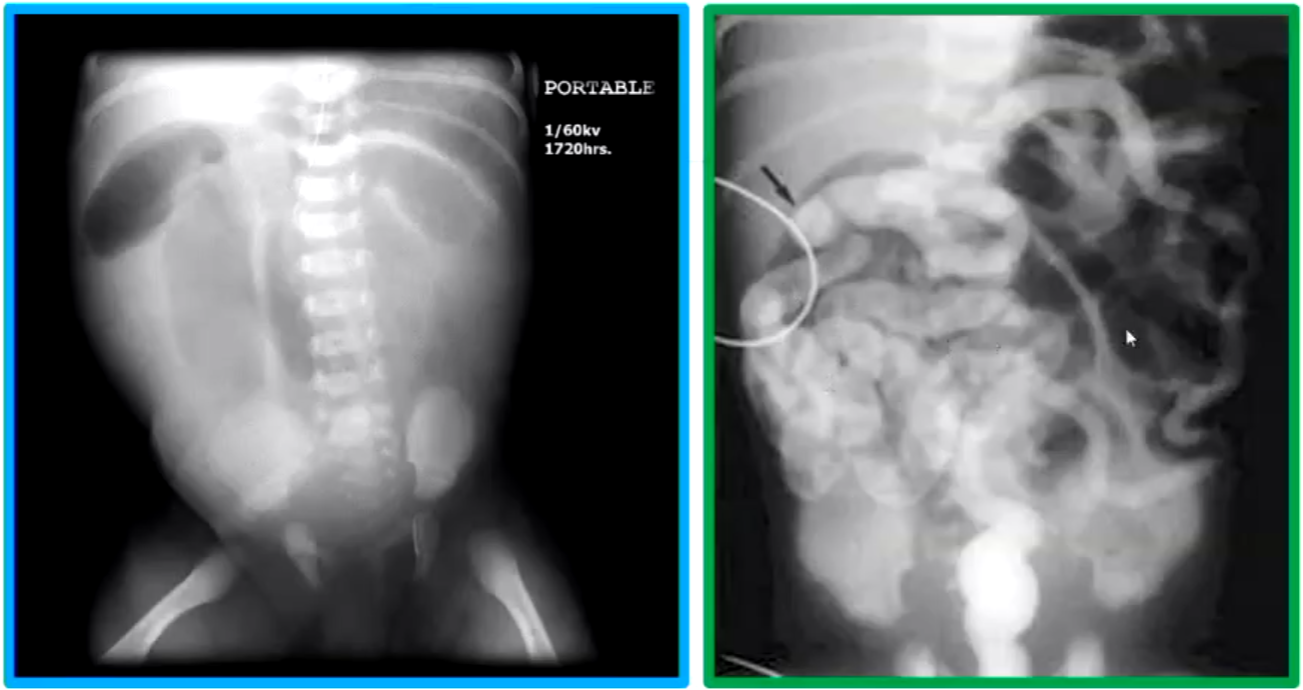

Meconium Plug Syndrome

Meconium plug syndrome is inspissated meconium creating a low-grade large bowel obstruction due to lack of colonic inertia, NOT thickened meconium as in a meconium ileus.

Associated with newborn infants and often with a diabetic mother.

The radiographic appearances are:

Distended ascending, transverse colon along with the terminal ileum.

A bubbly to largish clumping appearance in the large bowel.

No gas present in the rectum.

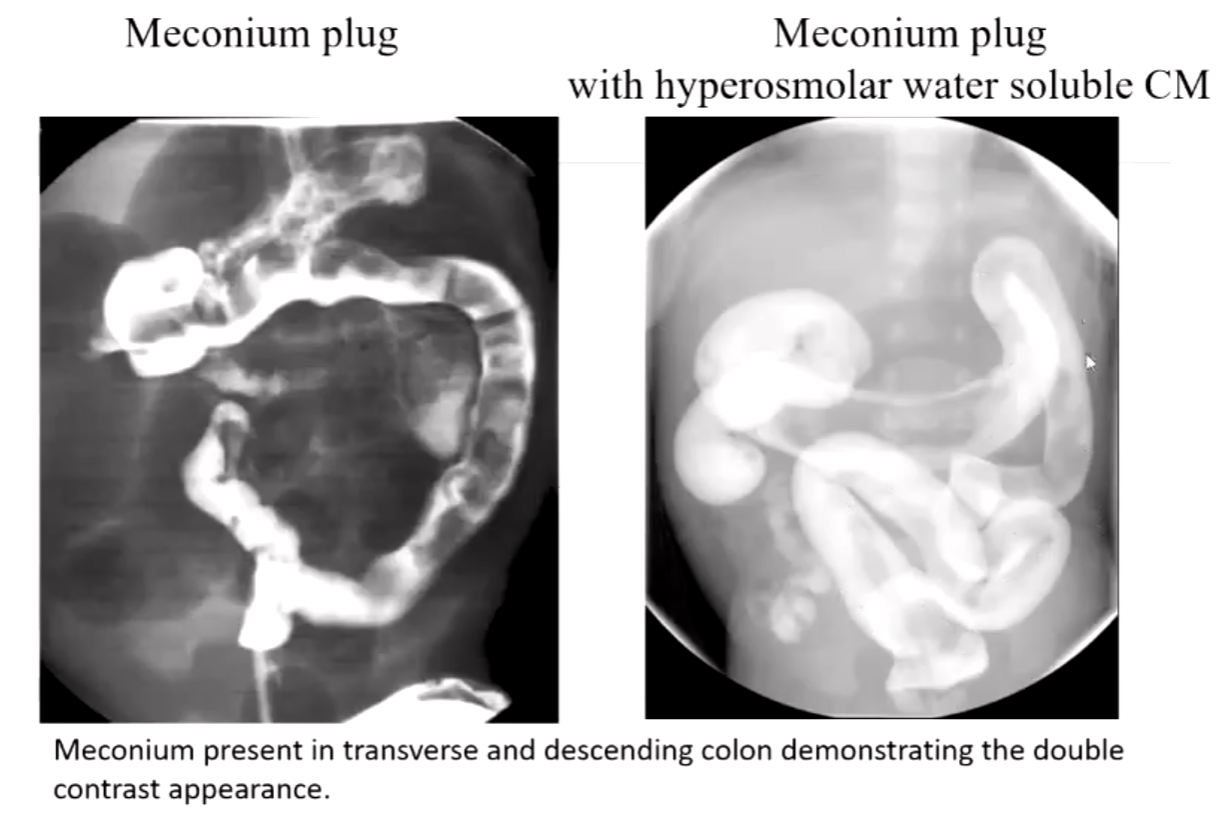

With a contrast enema, there can be a double contrast appearance – CM lying between the meconium plug and bowel wall.

Image Examples:

Meconium plug with hyperosmolar water-soluble CM.

Meconium present in transverse and descending colon demonstrating the double contrast appearance.

Malrotation of the Bowel

MALROTATION is congenital and is an abnormal rotation of the bowel.

Usually involves both the small and large bowel.

There can be abnormal fixation by mesenteric bands, or there can be an absence of mesenteric fixation of parts of the bowel.

Either way, there is an increased risk of an acute or chronic volvulus or obstruction.

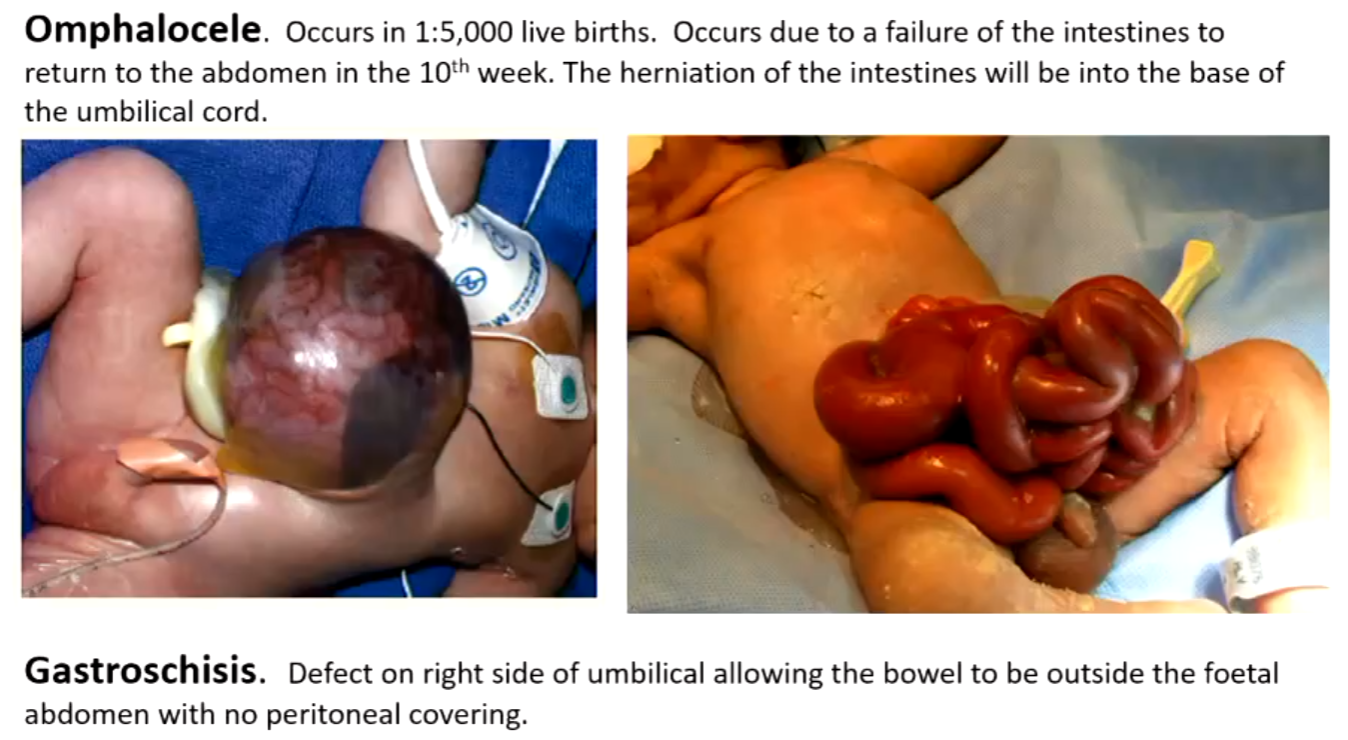

INTESTINAL MALROTATION covers a range of intestinal abnormalities from the omphalocele in the newborn to the asymptomatic “non-rotation” of small or large bowel in the adult.

A neonate with gastroschisis has a developmental perforation of the anterior abdominal wall near the umbilicus.

Gastroschisis: A congenital defect characterized by the extrusion of abdominal contents through a defect in the abdominal wall, leading to exposure of the intestines and other organs.

Omphalocele occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 live births, due to a failure of the intestines to return to the abdomen in the 10th week. The herniation of the intestines will be into the base of the umbilical cord.

Gastroschisis is a defect on the right side of the umbilical cord, allowing the bowel to be outside the fetal abdomen with no peritoneal covering.

MALROTATION is not a common condition; estimates are 3.9 per 10,000 live births.

Diagnosis is usually made in newborns or within the first year of life.

Associated congenital abnormalities are most common, including Meckel’s diverticulum, which also predisposes the child to intussusception, and Hirschsprung’s disease, an agangiolonic segment in the lower rectal section that causes periods of very long duration constipation.

CLINICAL PREDICTORS of MALROTATION and VOLVULUS in a neonate or young infant is vomiting. In older children, the presentation is varied and non-specific, leading to long delays in making a diagnosis.

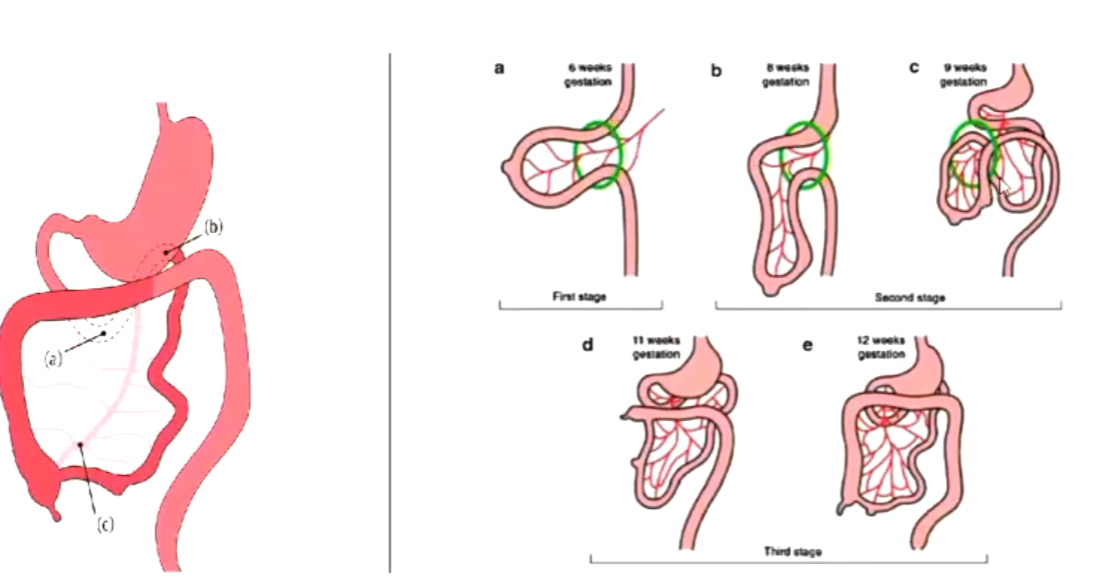

Stages of GIT development:

Diagram of normal intestinal rotation.

a. 6 weeks: bowel moves from intra-abdominal to extra-abdominal undergoing a 90-degree counterclockwise rotation.

b and c. re-entry to abdomen undergoing a 90-degree counterclockwise rotation.

d and e. conclusion of re-entry to abdomen undergoing the final 90-degree counterclockwise rotation with e being the normal positioning of small and large bowel.

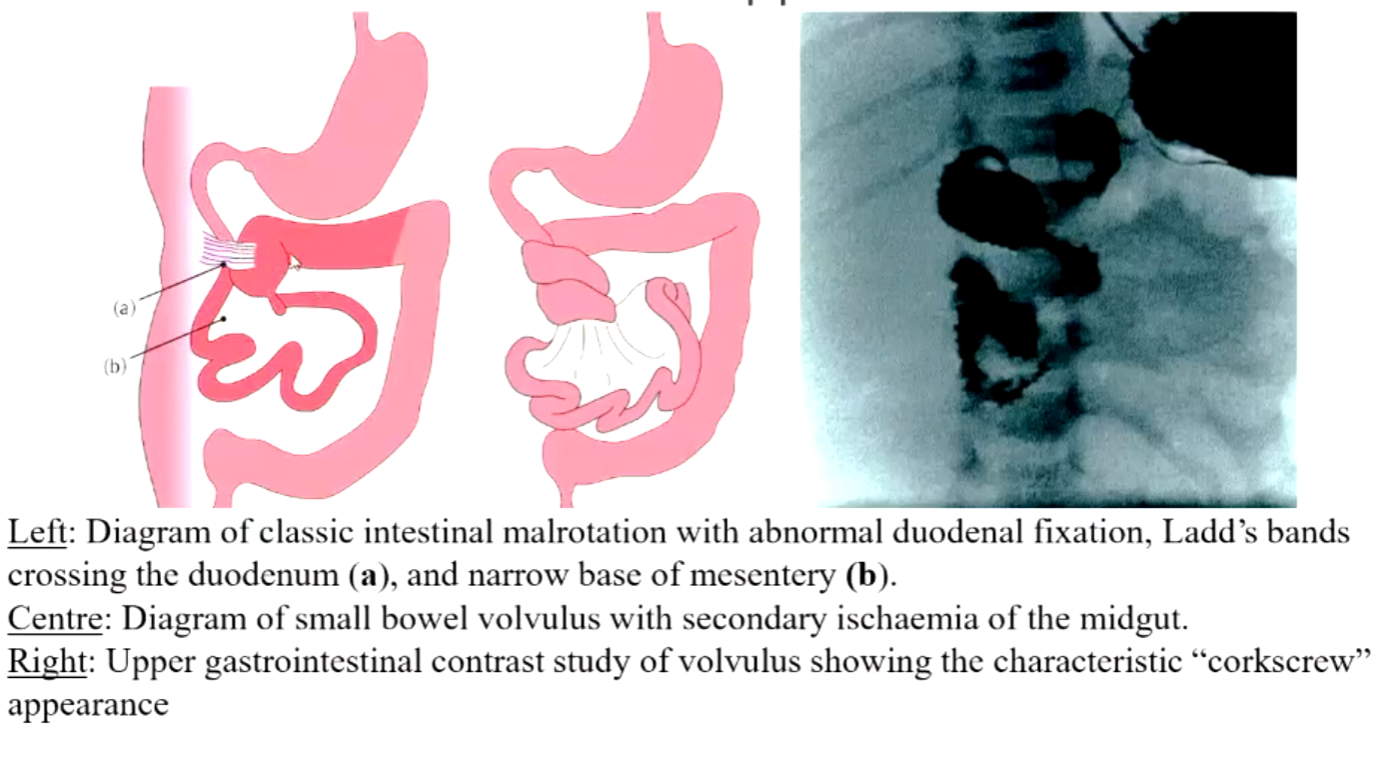

Malrotation with midgut volvulus:

Diagram of classic intestinal malrotation with abnormal duodenal fixation.

Ladd’s bands crossing the duodenum (a), and narrow base of the mesentery (b).

Diagram of small bowel volvulus with secondary ischemia of the midgut.

Upper gastrointestinal contrast study of volvulus showing the characteristic “corkscrew” appearance.

Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC)

Is an ischemic bowel disease secondary to hypoxia, perinatal distress, or infection.

Is the most common acquired and life-threatening gastrointestinal emergency in preterm, very low birth weight infants (1-13%) and 1-8% of infants admitted to NNIC.

Occurs in week 1-2 of life.

Risk factors:

PRETERM INFANT: GIT immaturity, immune host defense mechanisms, aggressive enteral feedings, mucosal insults (hypoxic/ischemic insults), polycythemia, PDA (patent ductus arteriosus), presence of bacteria in small lumen, NICU overcrowding, perinatal stress.

FULL-TERM INFANT: Congenital heart disease, coexisting conditions, aggressive enteral feedings, conditions compromising GI blood flow and/or oxygenation.

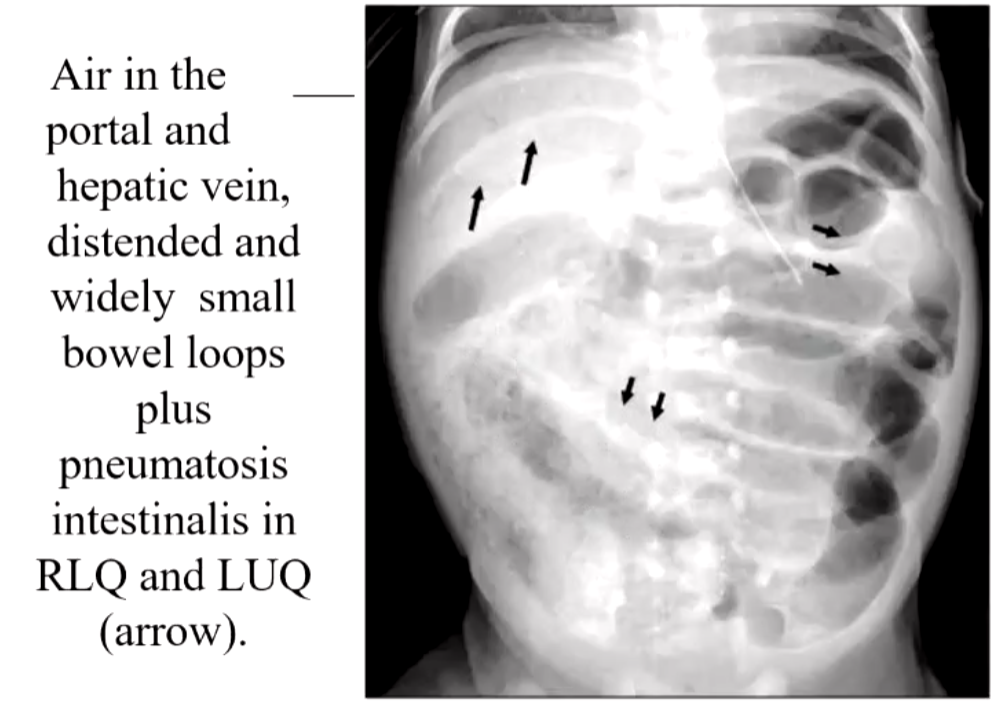

Some of the radiological abdominal signs:

Disorganization of bowel pattern.

Distension of the small bowel and colon +/- fluid levels initially in RLQ.

Fixed loops of bowel.

Pneumatosis intestinalis – definitely bowel necrosis – surgery may be required.

Bubbly appearance of the bowel – could be feces but almost certainly air in the wall.

Gas in the portal vein – as above.

Pneumoperitoneum – surgery required.

Barium enema is contraindicated, but a limited BE may be used on patients with clinical and radiological doubt; however, more commonly, a laparotomy is performed to settle questions of doubt.

Patients may undergo surgery to resect necrotic bowel but there are commonly post-op strictures, and BE is used in follow-up after surgery.

Bowel perforation occurs in approximately 1/3 of cases.

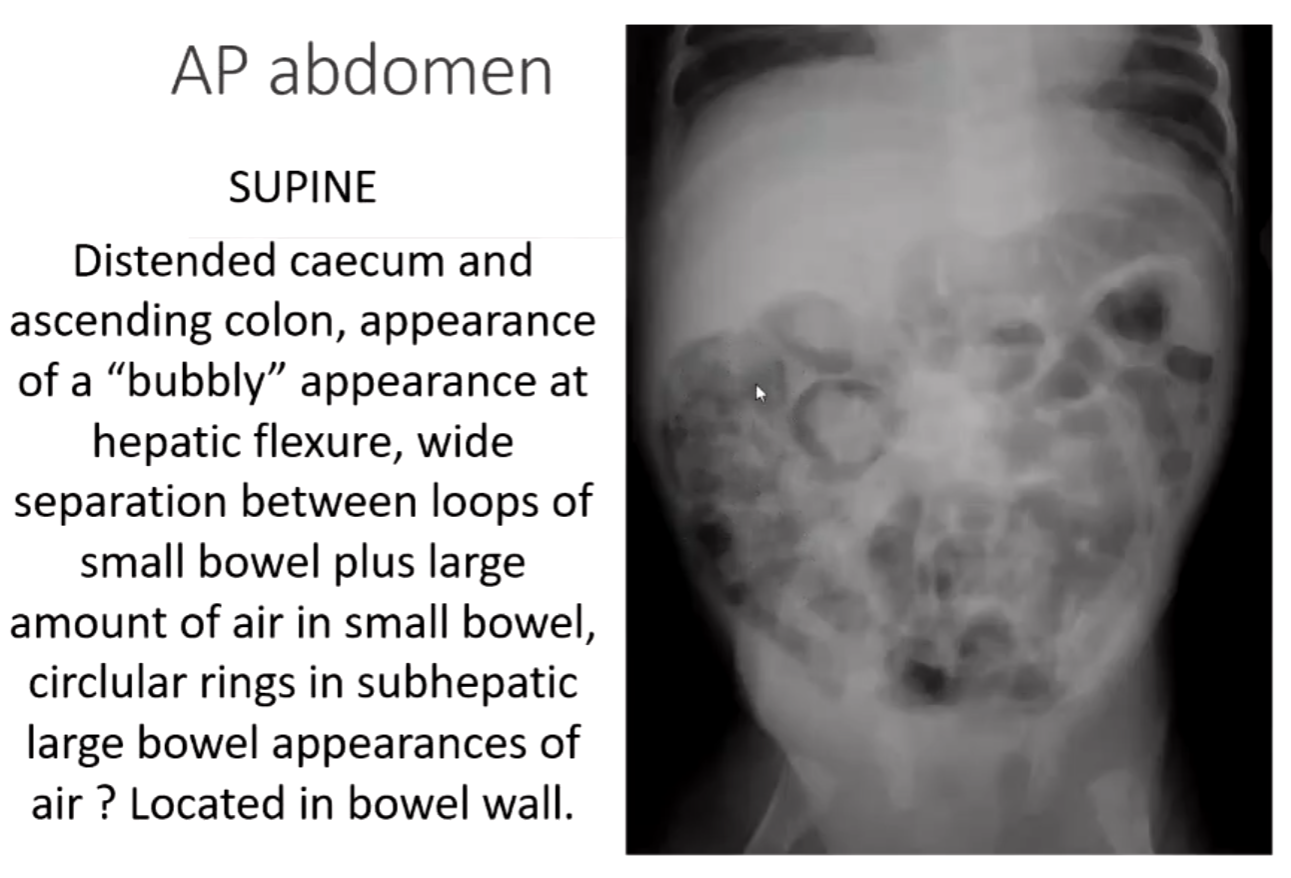

SUPINE: Distended caecum and ascending colon, appearance of a “bubbly” appearance at the hepatic flexure, wide separation between loops of small bowel plus a large amount of air in the small bowel, circular rings in subhepatic large bowel appearances of air located in the bowel wall.

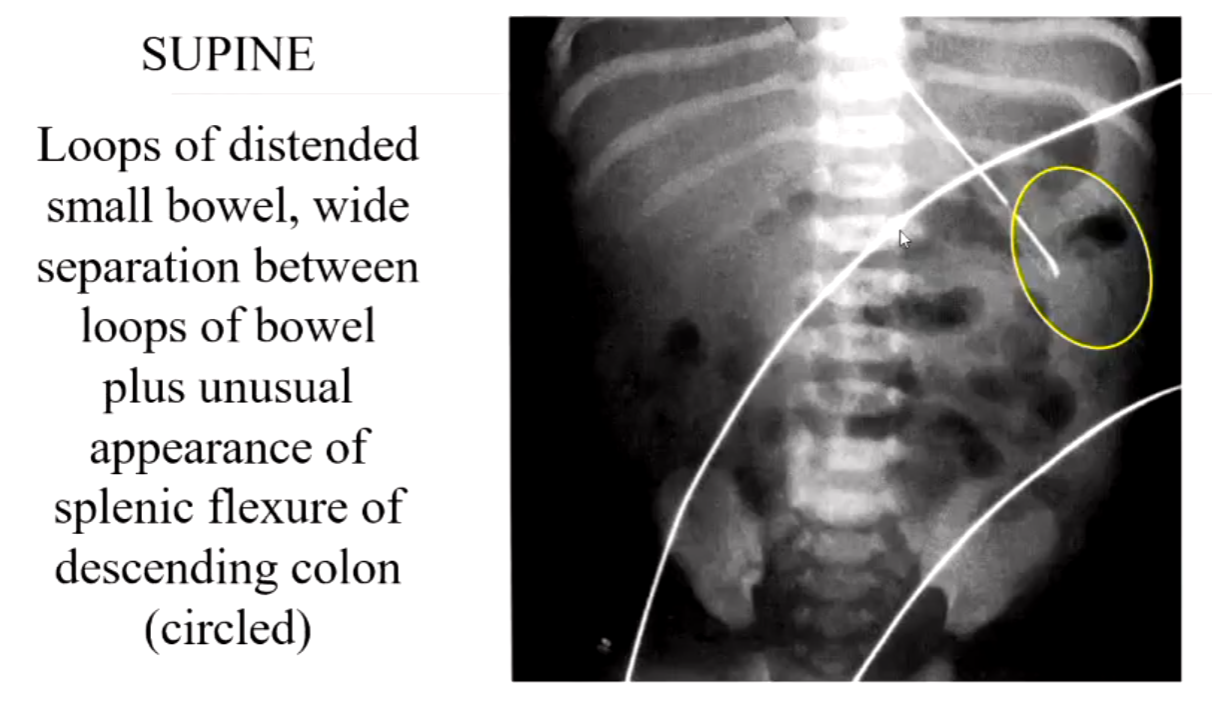

SUPINE: Loops of distended small bowel, wide separation between loops of bowel plus an unusual appearance of the splenic flexure of the descending colon.

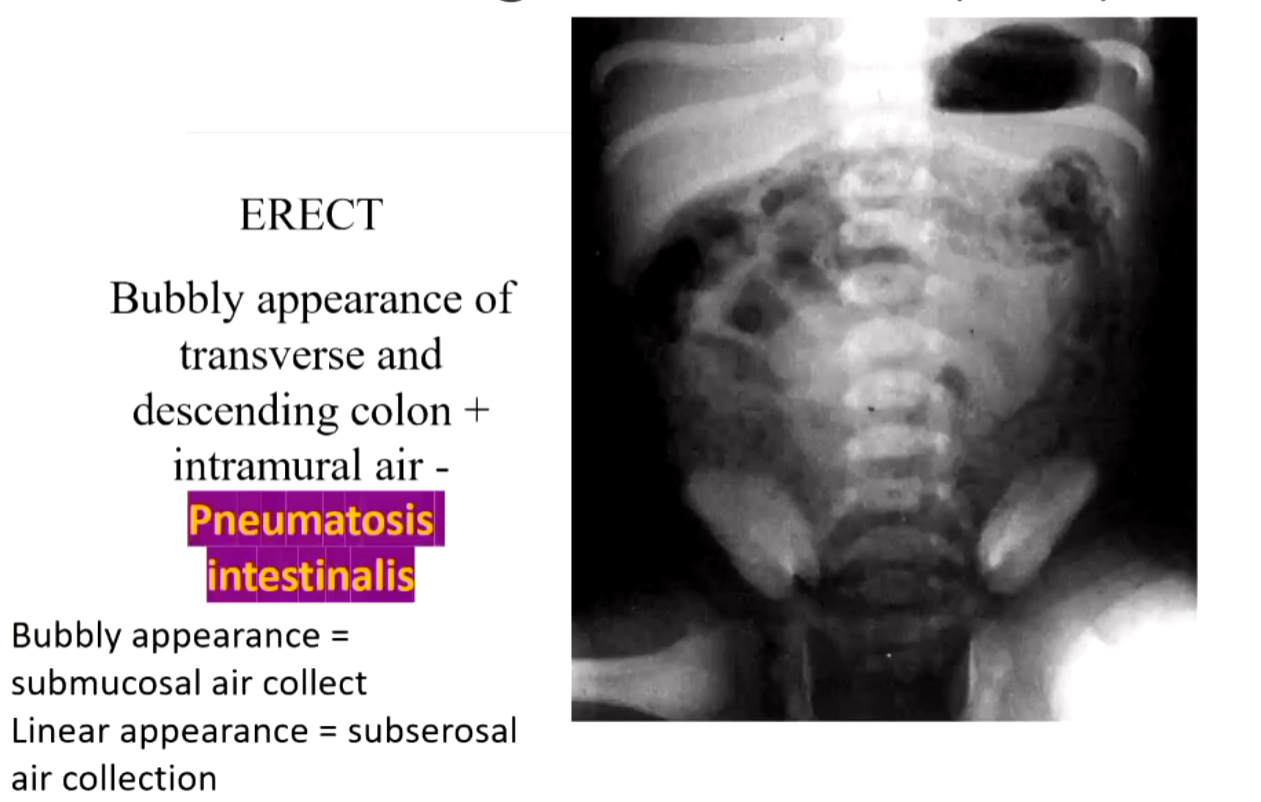

ERECT: Bubbly appearance of the transverse and descending colon + intramural air - Pneumatosis intestinalis. Bubbly appearance = submucosal air collect. Linear appearance = subserosal air collection.

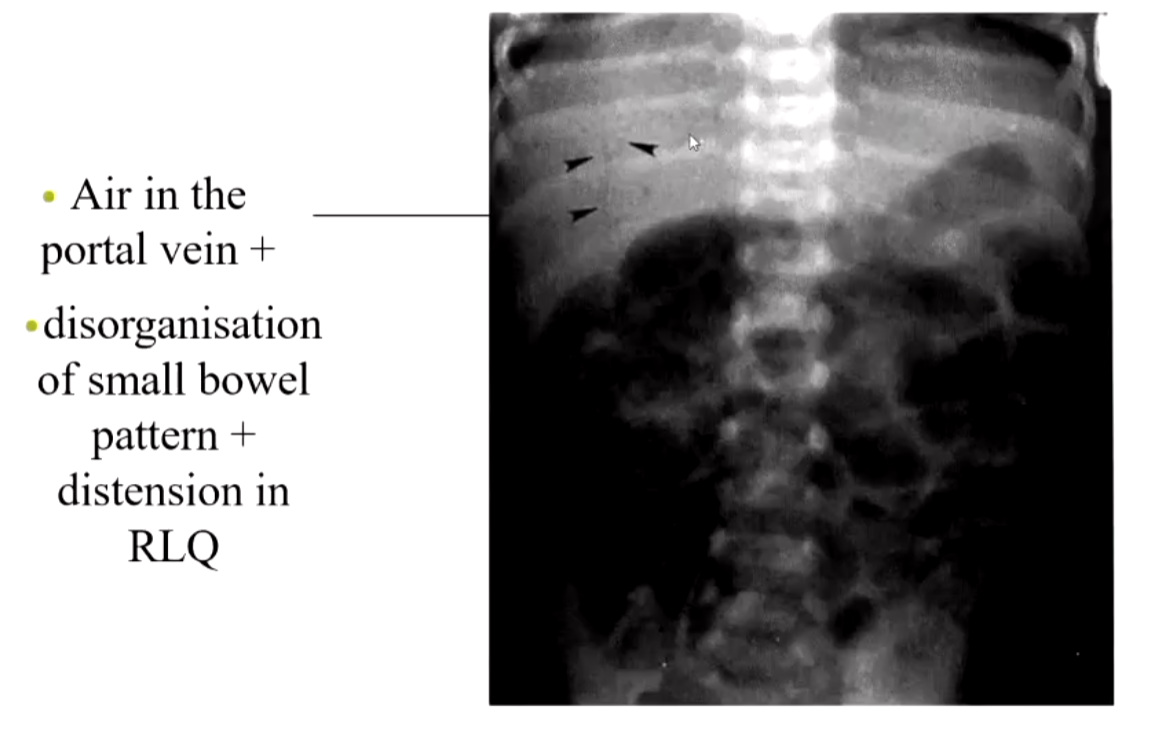

Air in the portal vein + disorganization of small bowel pattern + distension in RLQ.

Air in the portal and hepatic vein, distended and widely separated small bowel loops plus pneumatosis intestinalis in RLQ and LUQ.

Imperforate Anus

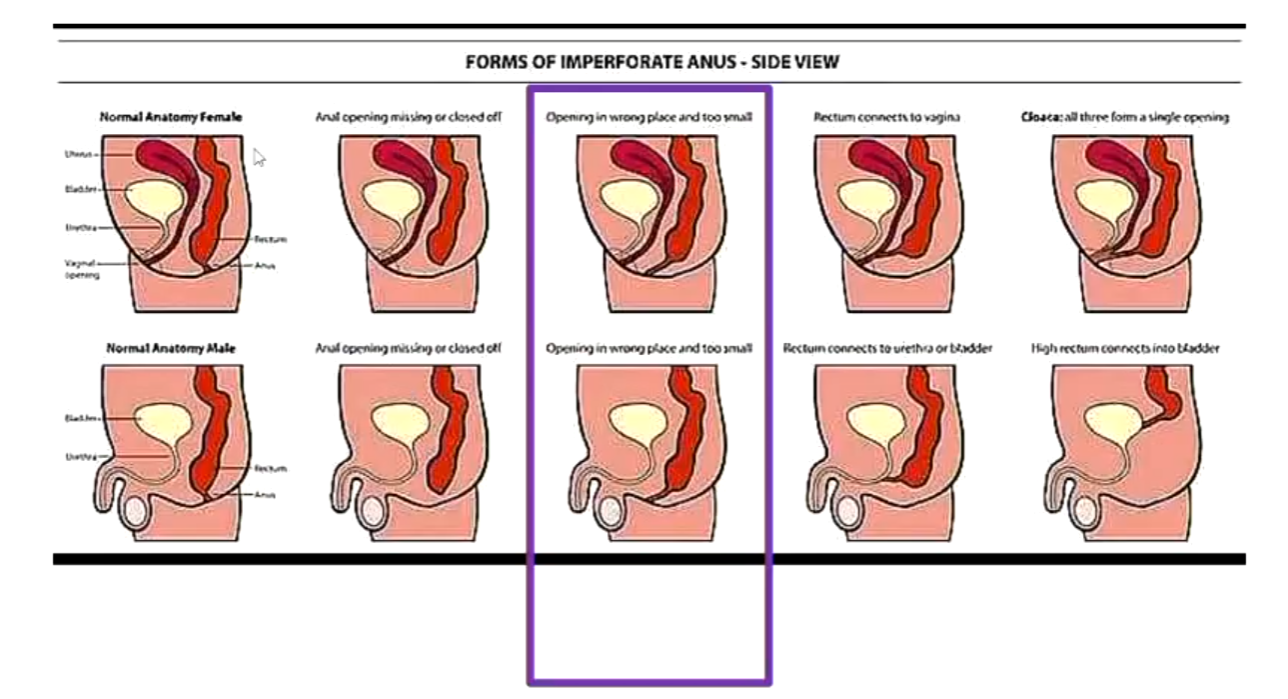

Includes agenesis and atresia of the rectum and anus.

Etiology: unknown.

Incidence: 1 in 4,500.

SEX: 60% male.

Forms of imperforate anus-side view:

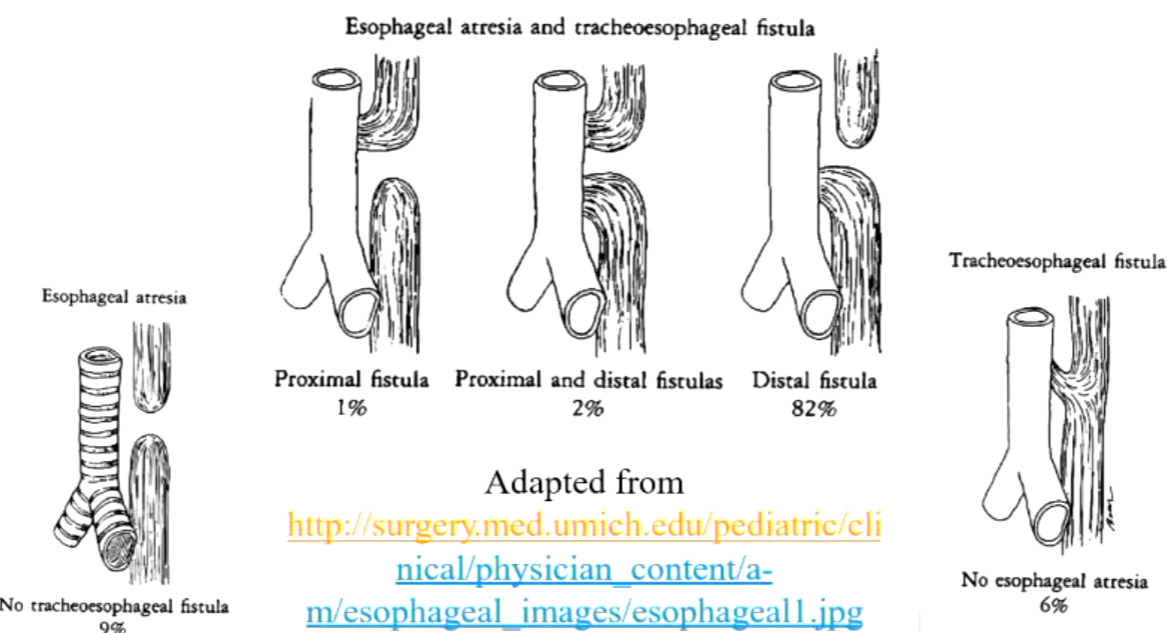

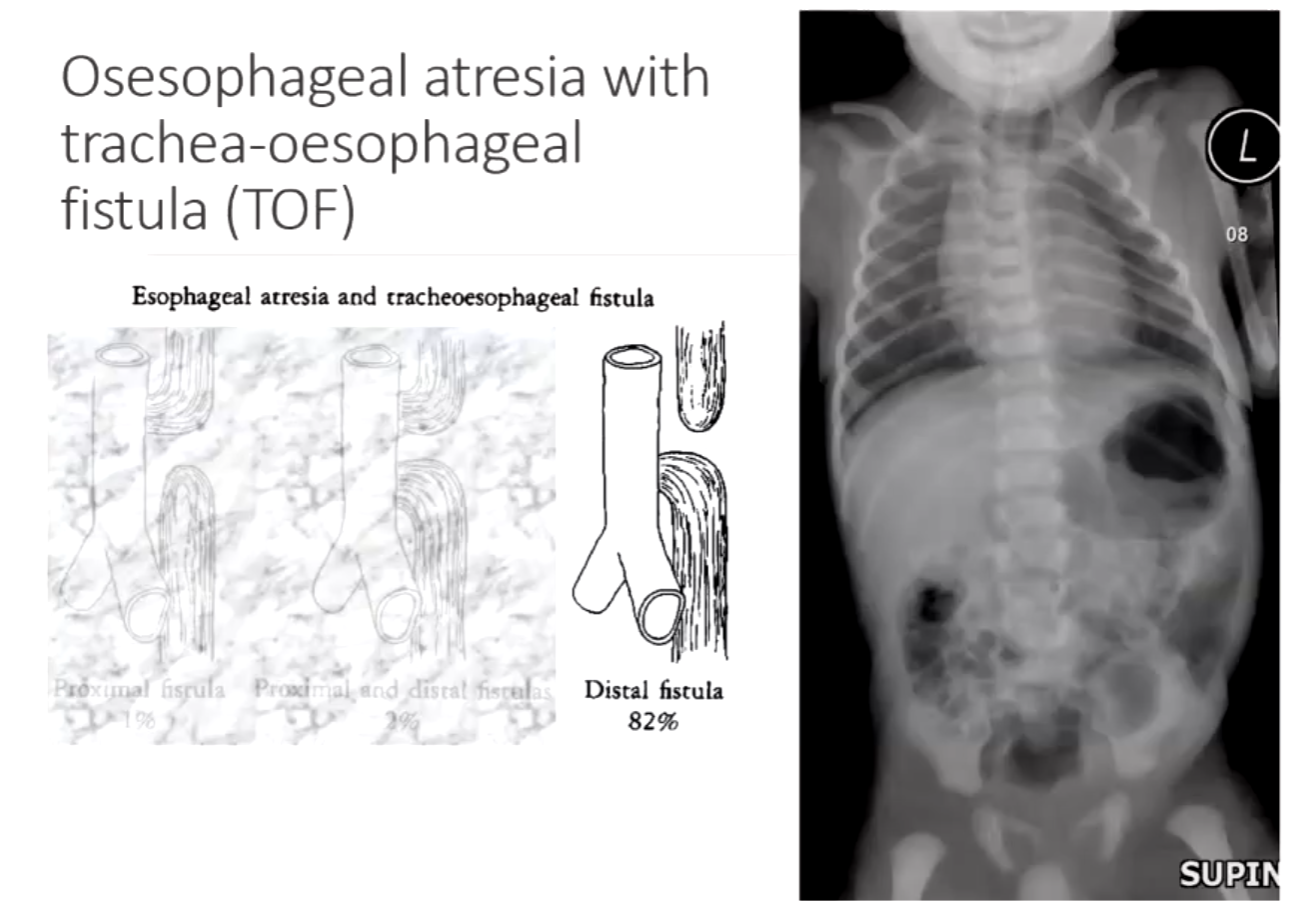

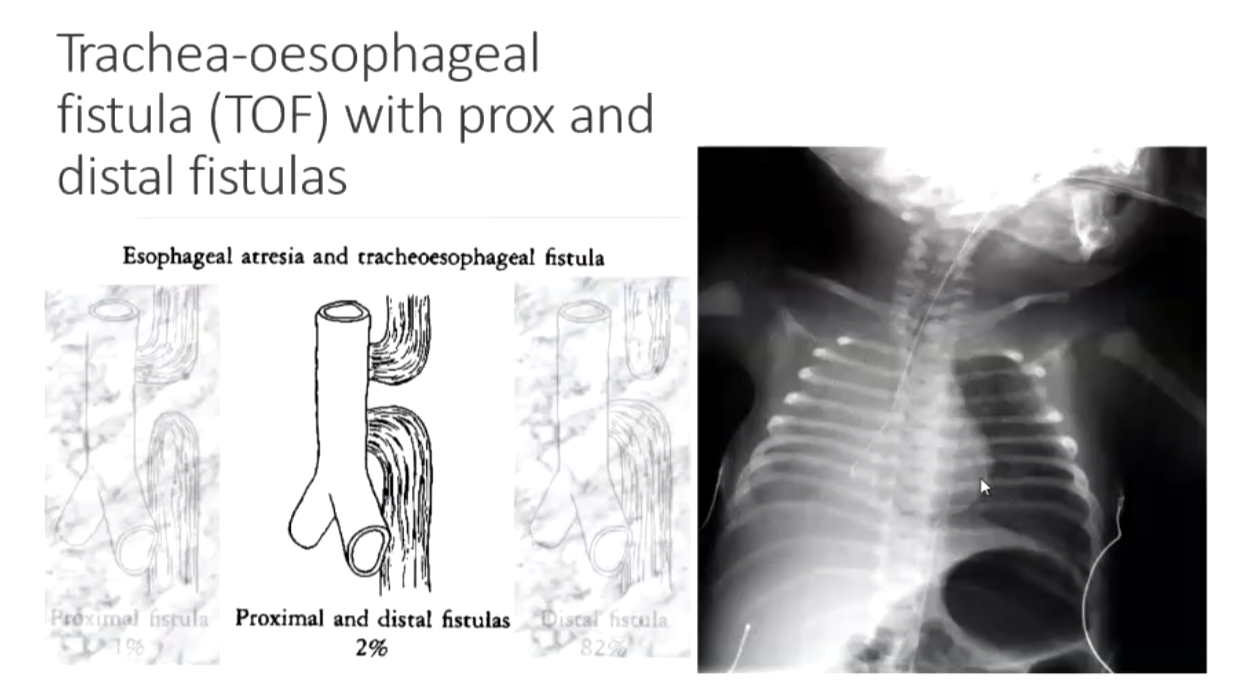

Oesophageal Atresia or Tracheo-Oesophageal Fistula (TOF or TEF)

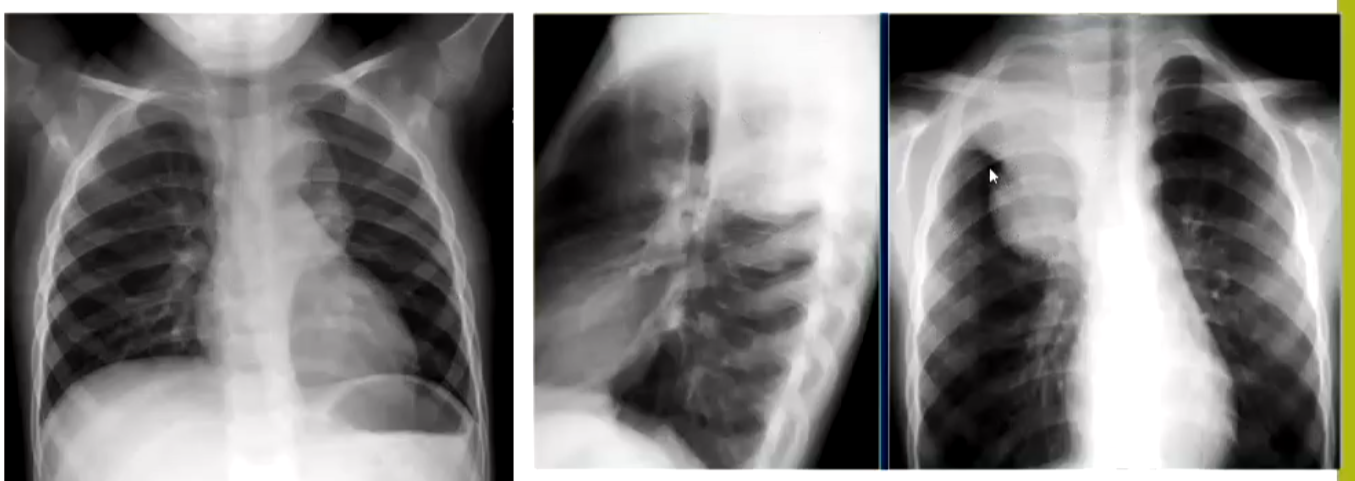

Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula:

Distal fistula (82%)

Proximal fistula (1%)

Proximal and distal fistulas (2%)

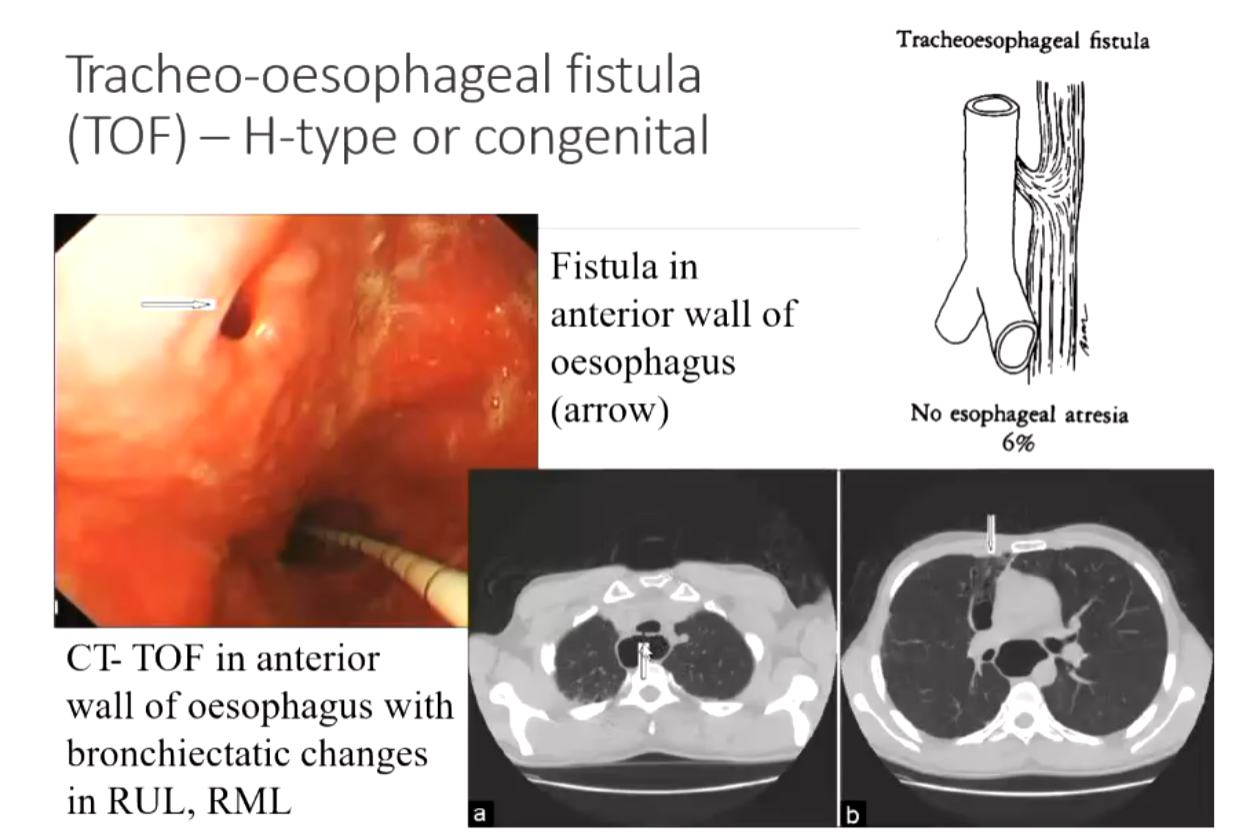

Tracheoesophageal fistula

No esophageal atresia (6%)

Esophageal atresia

No tracheoesophageal fistula (9%)

SIGNS and SYMPTOMS:

Frothy, white bubbles in the mouth.

Coughing or choking when feeding.

Vomiting.

Blue color of the skin, especially when the baby is feeding.

Difficulty breathing.

Very round, full abdomen.

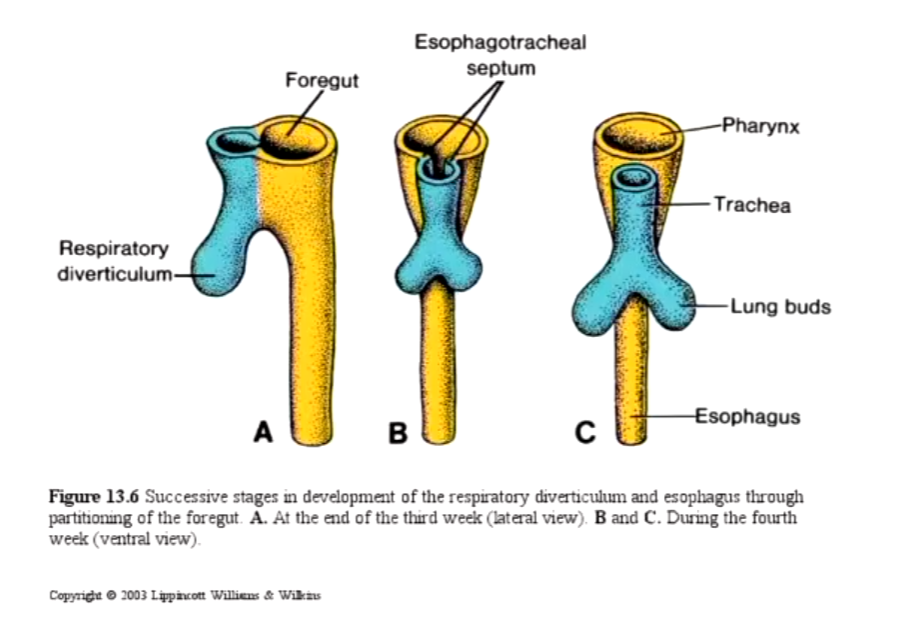

Development of respiratory and esophagus:

Successive stages in the development of the respiratory diverticulum and esophagus through partitioning of the foregut.

Possible co-morbidities of pts:

Trisomy 13, 18, or 21

Other digestive tract problems (such as diaphragmatic hernia, duodenal atresia, or imperforate anus)

Heart problems (such as ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, or Patent Ductus Arteriosis)

Kidney and urinary tract problems (such as horseshoe or polycystic kidney, absent kidney, or hypospadias)

Muscular or skeletal problems

VACTERL syndrome (which involves Vertebral, Anal, Cardiac, TE fistula, Renal, and Limb abnormalities)

Tracheo-oesophageal fistula (TOF) – H-type or congenital:

Fistula in the anterior wall of the esophagus.

CT-TOF in the anterior wall of the esophagus with bronchiectatic changes in RUL, RML.

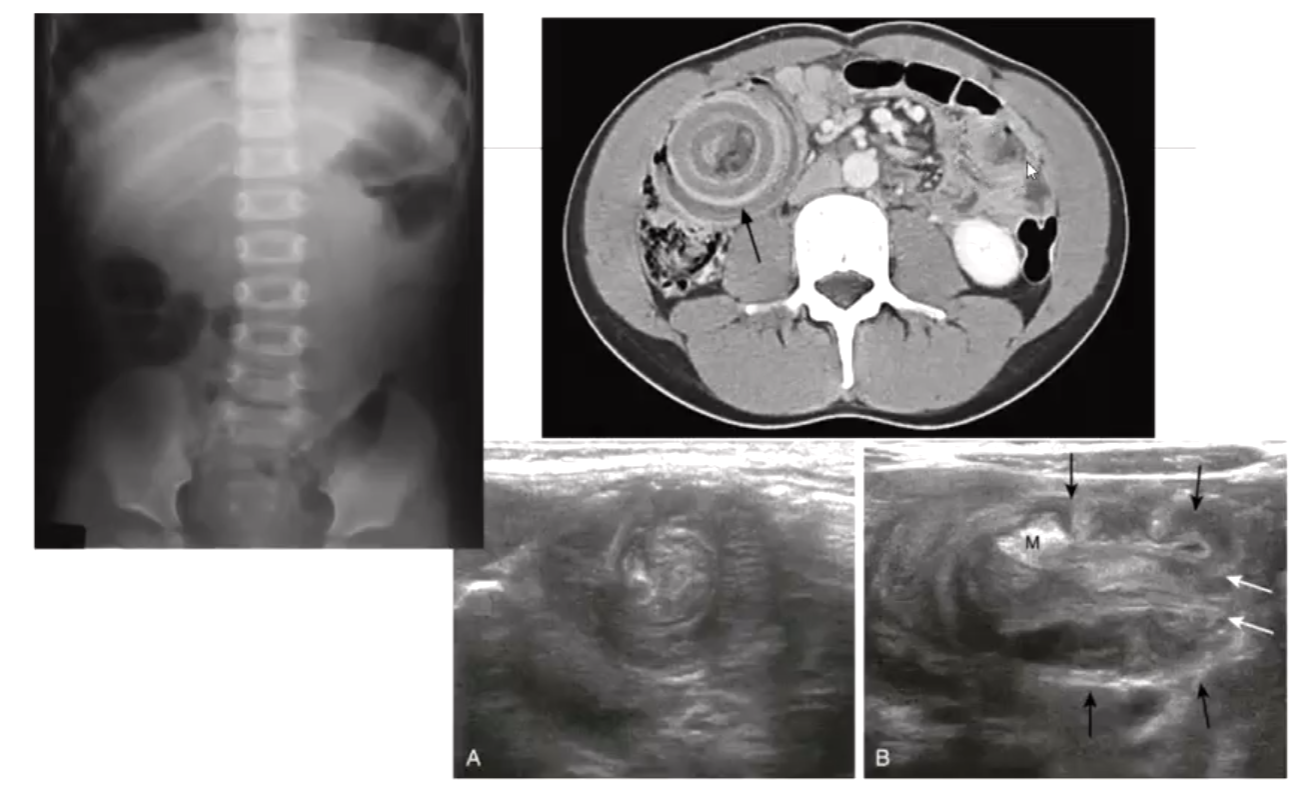

Intussusception

An INTUSSUSCEPTION is formed by the proximal bowel (Intussusceptum) which is hyperactive forcing itself into the distal bowel (Intussuscipiens) which is not hyperactive.

Ischemia is a potential complication if the intussusception is not diagnosed early enough.

Clinical signs intussusceptions:

History:

Early: Patients with intussusception typically develop the sudden onset of intermittent, severe, crampy, progressive abdominal pain, accompanied by inconsolable crying and drawing up of the legs toward the abdomen. Between symptoms child will be playing and doing normal activity. Vomiting

Later: Continuous abdominal pain. The stool may contain gross or occult blood or be a mixture of blood and mucous and sloughing mucosa, giving it the appearance of currant jelly. Lethargy

Physical:

A sausage-shaped abdominal mass.

Abdominal distension.

Redcurrant jelly stool.

Dehydration.

Epidemiology:

Epidemiology varies from country to country.

Patient age: 2 months – 2 years but is most common in the first year.

Male:female - this varies from different surveys but overall males are slightly more prevalent.

A lead point for the intussusception is a disease present in approximately 10% of the patients. A lead point for an intussusception is a bowel pathology which is either small bowel polyps, Meckel’s diverticula, duplication cysts, small bowel lymphomas, or submucosal bleeds. However, the remaining 90% of cases are idiopathic.

Imaging and reduction of intussusceptions:

Plain abdomen lacks the sensitivity to detect the presence of an intussusception – sensitivity approximately 0.45

DIAGNOSIS US is the first modality for diagnosis, then CT and MRI for more complicated cases.

REDUCTION Once an intussusception has been diagnosed, the patient needs to be medically stabilized, and a method of non-operative reduction needs to be conducted. If this is successful, then a surgical reduction will not be required; however, if it is not a complete reduction, then it is either repeated or a surgical reduction is performed.

The initial reduction is via an enema which is either 0.9N saline (Hartmann’s solution) or air-based. It must be performed by a specialized radiologist and should have members of the surgical team present. The progress of the reduction is via US or fluoroscopy, depending upon the contrast medium used. The surgical team needs to be present to manage any possible complication, with the most severe complication being a tension pneumoperitoneum.

Reduction of intussusception:

The infant should be given analgesia before the reduction. An inflatable balloon catheter is inserted into the rectum, and the buttocks are either held together by hands or taped together, so there is as good as possible water seal around the catheter.

The rule of THREEs is then applied:

1. a pressure monitoring device needs to be used with a max pressure of 120mm Hg set

2. three attempts made to reduce the intussusception with pressures increasing from 80-100mm Hg.

3. each attempt to be maintained for 3 minutes.

For the reduction to be complete, there needs to be a free flow of air or saline into the terminal ileum. If the reduction does not occur, then the infant will either need to have another reduction attempted in 4-6 hours provided they are clinically well, otherwise a surgical reduction will be performed via laparotomy. An air reduction is successful in 75-90% of cases, and a hydrostatic reduction is successful in approximately 90% of cases.

Complication of intussusception reduction:

The major complication of a reduction is bowel perforation. If a perforation occurs, then due to the pressure used, a high-pressure pneumoperitoneum can result and cause a reduction in the venous return for the lower body leading to cardiovascular collapse. The perforation could be from a small necrotic patch or can be a long, linear tear. The risk of a tear is greater in late-presenting intussusceptions.

The recurrence rate for an intussusception is < 5%, and parents will recognize the next episode more promptly, avoiding an intussusception becoming advanced.

Early Childhood Tumours

Neuroblastoma

Nephroblastoma - Wilms' tumour

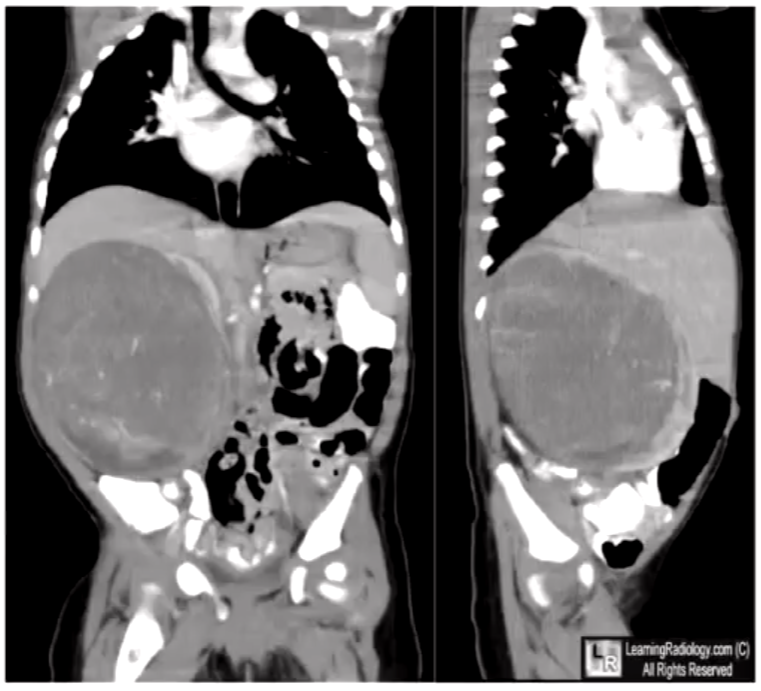

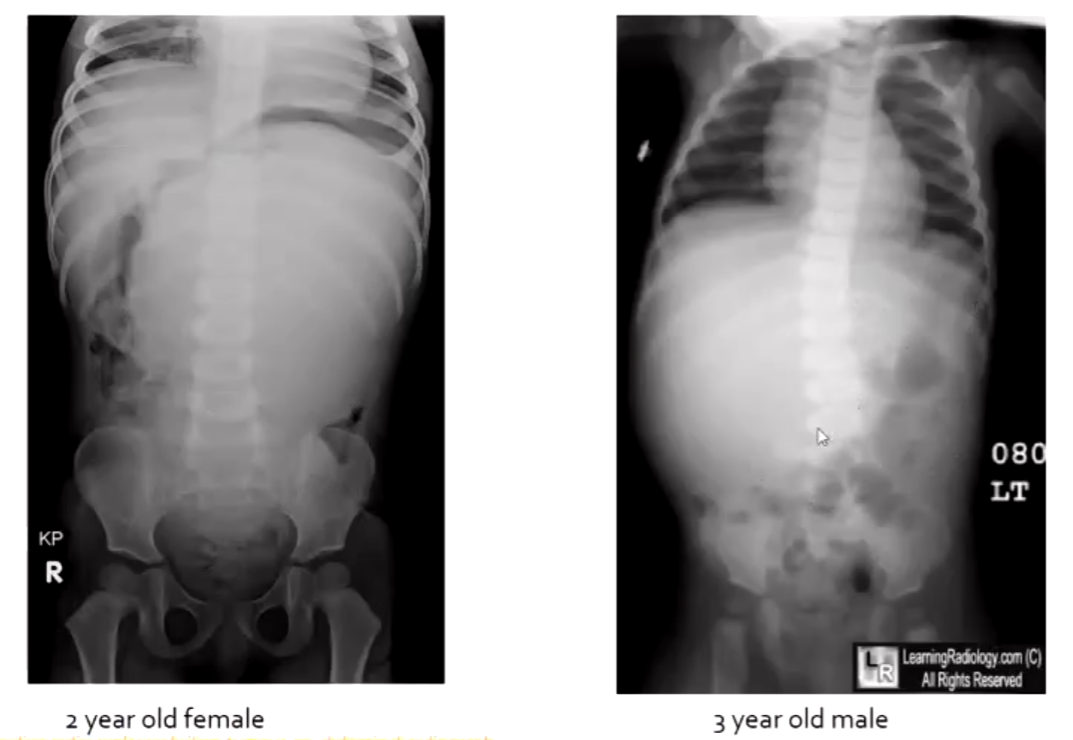

WILMS TUMOUR (NEPHROBLASTOMA)

Most common malignant abdominal tumor in children aged 1-8 years.

Is the 3rd most common malignancy in children after leukemia and brain tumor.

Comes 3rd most common kidney mass in children after hydronephrosis and multicystic dysplastic kidney.

NEUROBLASTOMA – involves adrenal gland

< 2yrs 50%

< 4yrs 75%

< 8yrs 80%

Peak presentation is 3 years

Neuroblastoma are derived from cells that give rise to the sympathetic nervous system.

Histologically, neuroblastoma has a classic appearance – biopsy, urine, and blood analysis are critical for diagnosis.

Most common sites for a neuroblastoma are:

adrenal medulla (30%)

extra-adrenal paraspinal ganglia (30-35%)

posterior mediastinum (20%)

Slightly more common in males

Prevalence is one case in 7,000 live births

Median age at diagnosis is 19 months

The incidence rapidly declines after 1 year old

Patients < 1 year old tend to have a better prognosis, even with mets, than patients > 1 year old

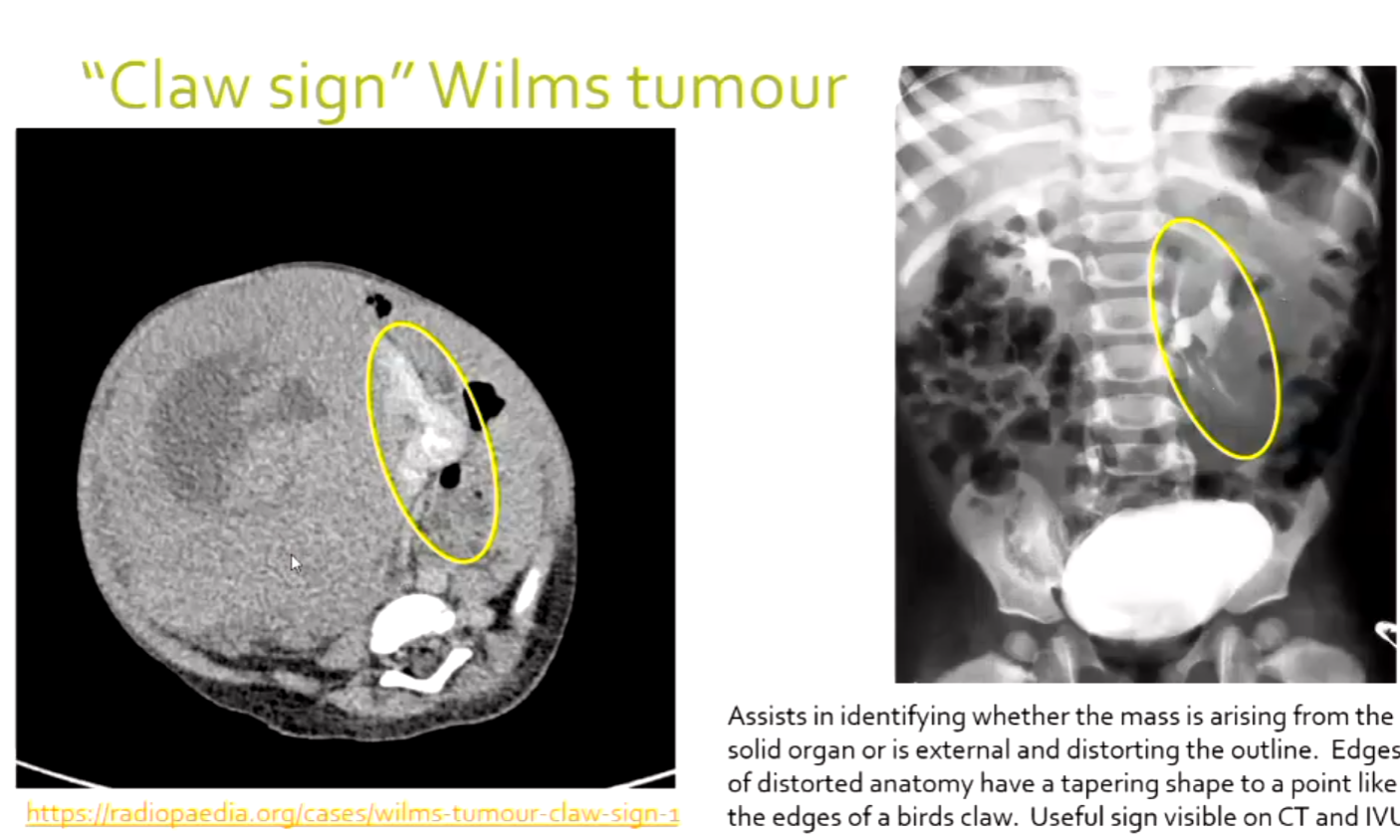

"Claw sign" Wilms tumour

Assists in identifying whether the mass is arising from the solid organ or is external and distorting the outline.

Edges of distorted anatomy have a tapering shape to a point like the edges of a bird's claw.

Useful sign visible on CT and IVU.

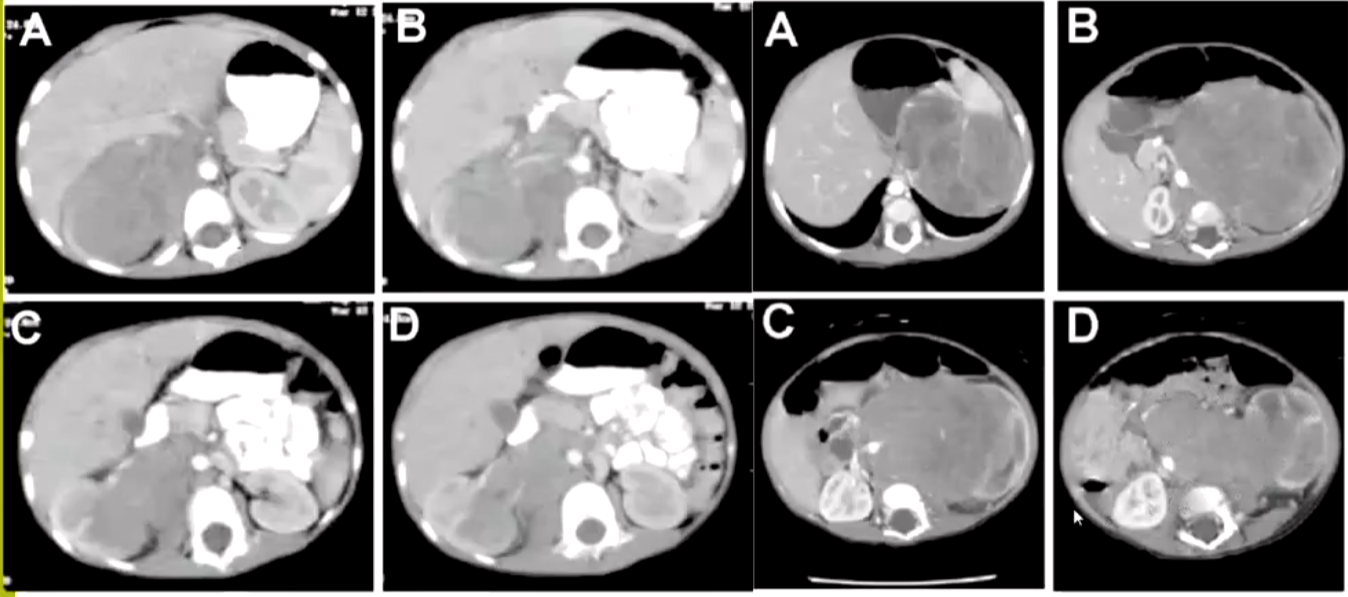

Summary of features of neuroblastoma & nephroblastoma

Feature | Neuroblastoma | Nephroblastoma (Wilms tumour) |

|---|---|---|

Age | < 2 years | Peak 3 – 4 years |

Frequency | MOST COMMON SOLID EXTRACRANIAL TUMOUR IN CHILDREN, bilateral very rare | MOST COMMON RENAL TUMOUR IN CHILDREN (often cystic components). 3% bilateral |

Calcification | Common (80-90%), with a stippled pattern | Uncommon 10-15%, curvilinear pattern |

Growth pattern | Surrounds and engulfs vessels – commonly crosses the midline in the abdomen behind the aorta. Poorly marginated tumour border. | Displaces vessels – may / may not cross the midline in the abdomen. Clearly marginated tumour. |

Effect on kidneys | Mainly involves the adrenal gland. Results in inferior displacement and rotation | Arises from the kidney – has a ‘claw-like appearance’ |

Mets. | Bone, bone marrow/ liver common with lung rare | Lung (20% cases), 50-69% have bone, liver or lymph mets at presentation |

Vascular invasion | Usually encases and displaces the aorta anteriorly | Yes - renal vein, IVC, right atrium |

Presentation | Painful abdominal mass | Painless abdominal mass |