Chapter 7: Control of Gene Expression

An Overview of Gene Control

Gene control refers to the regulatory mechanisms that determine when, where, and to what extent genes are expressed or "turned on" in an organism.

Gene control is essential for proper development, cellular differentiation, and response to environmental cues.

The regulation of gene expression can occur at multiple levels, including.

- DNA, transcription

- RNA processing

- translation

- post-translational modifications.

One of the primary mechanisms of gene control is the binding of transcription factors to specific DNA sequences known as regulatory elements.

Transcription factors are proteins that can activate or repress gene expression by binding to regulatory elements, such as promoters, enhancers, or silencers.

Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, play a crucial role in gene control by influencing the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors and the transcriptional machinery.

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the DNA molecule, often resulting in gene silencing.

Histone modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, can alter the structure of chromatin and either promote or inhibit gene expression.

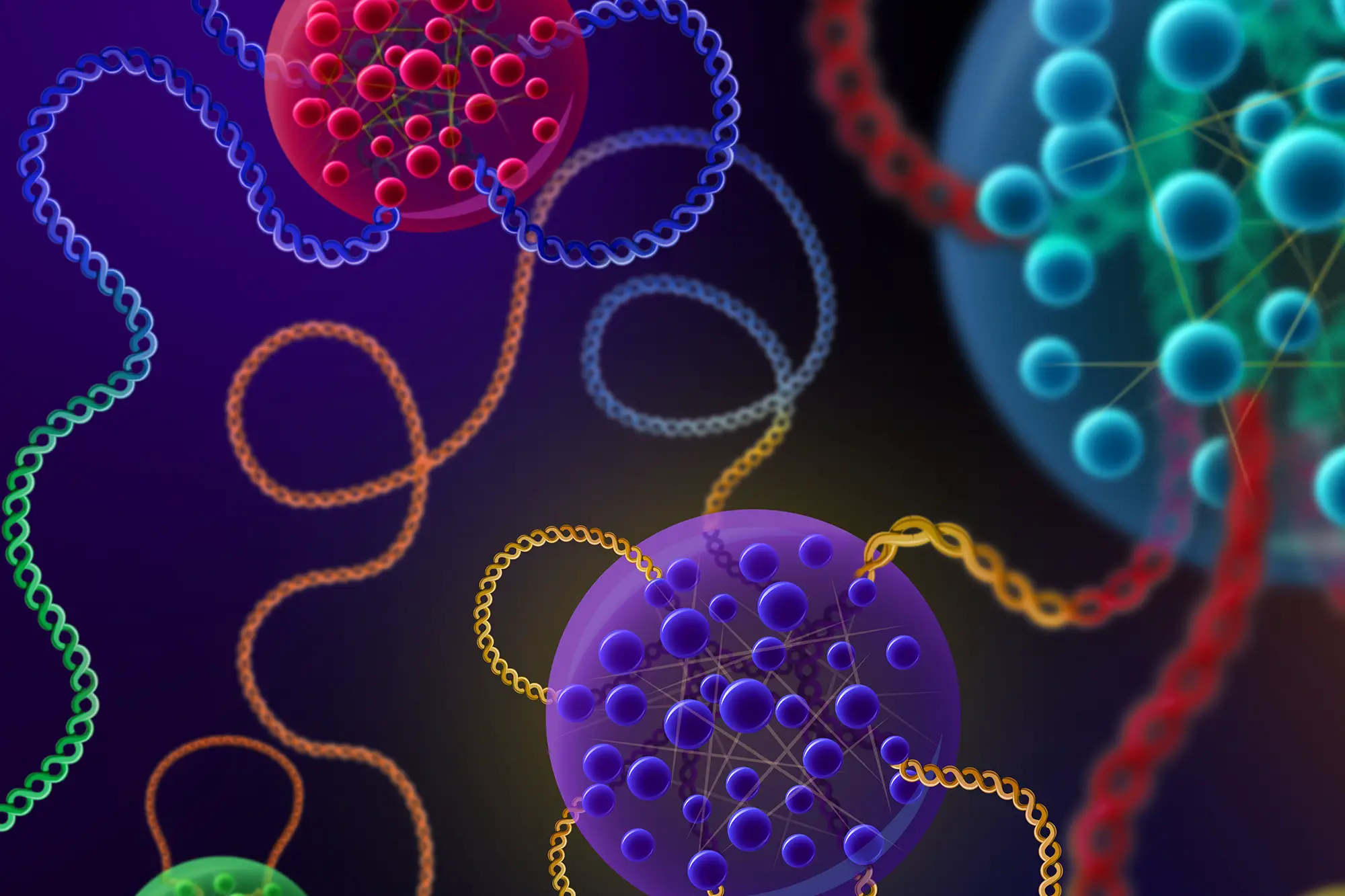

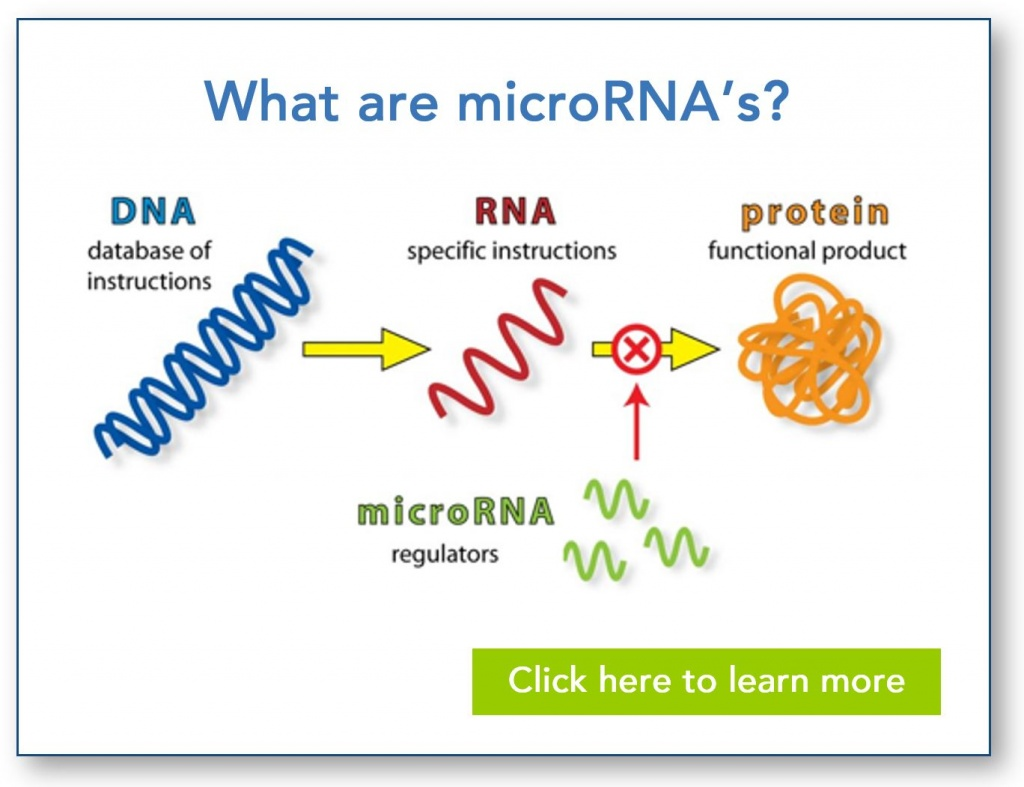

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), can also regulate gene expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level.

miRNAs are small RNA molecules that bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, preventing their translation into proteins or leading to their degradation.

lncRNAs are longer RNA molecules that can interact with DNA, RNA, or proteins, influencing gene expression through various mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling or mRNA stability.

Alternative splicing is a process that allows the production of multiple protein isoforms from a single gene by selectively including or excluding specific exons during mRNA processing.

Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, or ubiquitination, can regulate the activity, localization, and stability of proteins.

Gene control is a highly dynamic and complex process that involves the interplay of multiple regulatory elements, transcription factors, epigenetic modifications, and non-coding RNAs.

Control of Transcription by sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins

- Transcription is the process by which genetic information encoded in DNA is converted into RNA.

- The control of transcription is crucial for:

- regulating gene expression

- determining cell identity and function.

- Sequence-specific DNA binding proteins are also known as transcription factors.

- It plays a central role in controlling transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences in the regulatory regions of genes.

- Transcription factors can either activate or repress gene expression, depending on their mode of action and the context of the regulatory elements they bind to.

- The DNA sequences recognized by transcription factors are typically short and specific, consisting of a particular nucleotide sequence pattern.

- The binding of transcription factors to DNA regulatory elements is mediated by specific protein domains, such as:

- DNA-binding domains, that interact with the DNA molecule.

- Different families of DNA-binding domains are responsible for the recognition of specific DNA sequences, including:

- helix-turn-helix

- zinc finger

- leucine zipper

- basic helix-loop-helix domains.

- The binding specificity of transcription factors is determined by:

- the amino acid residues within their DNA-binding domains

- their interactions with the nucleotide bases in the DNA sequence.

- Regulatory regions of genes that are recognized by transcription factors include promoters, enhancers, silencers, and response elements.

- Promoters are DNA sequences located near the transcription start site that provide binding sites for transcription factors and RNA polymerase, initiating transcription.

- Enhancers are regulatory elements that can be located far away from the gene they control and interact with promoters through DNA looping, enhancing transcription.

- Silencers are regulatory elements that repress gene expression by interacting with transcription factors or blocking the binding of activators.

- Response elements are DNA sequences that are recognized by specific transcription factors in response to signaling pathways or environmental cues.

- Transcription factors can function as activators by recruiting the transcriptional machinery, including RNA polymerase and coactivator proteins, to the promoter region of genes.

- Activator transcription factors often have activation domains that interact with components of the transcriptional machinery, leading to the initiation of transcription.

- Transcription factors can also act as repressors by inhibiting the binding of activators or recruiting corepressor proteins that inhibit transcriptional activity.

- The expression and activity of transcription factors themselves can be regulated by various mechanisms, including post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and intracellular signaling pathways.

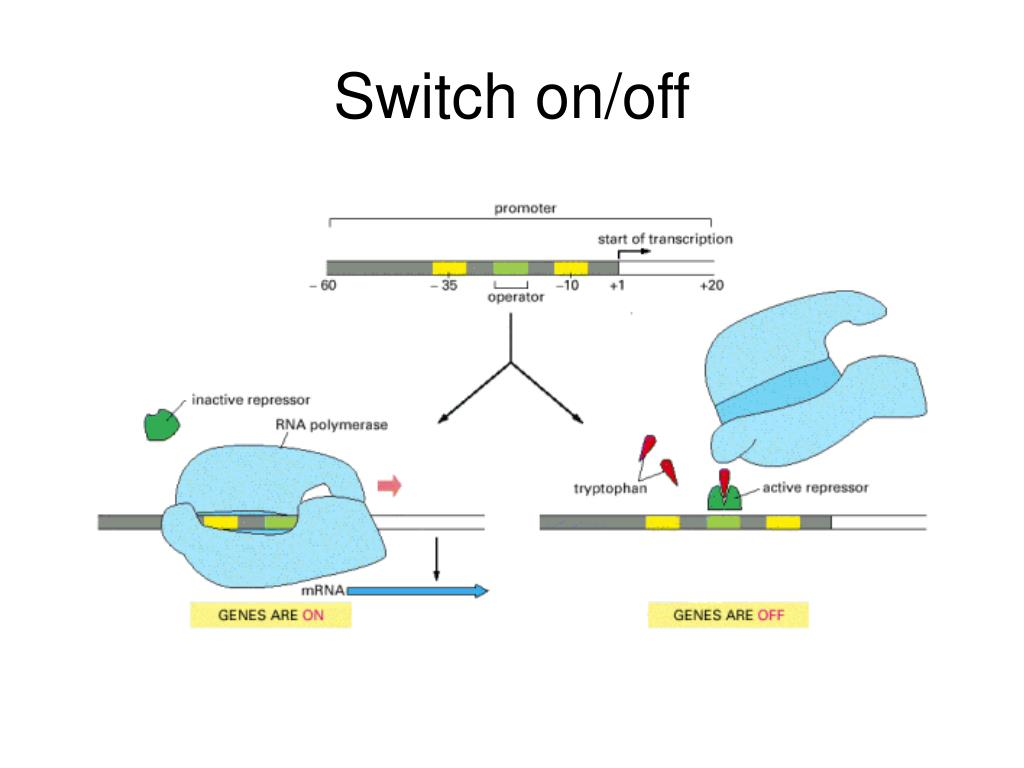

Transcription Regulators switch genes on and off

Transcription regulators, also known as transcription factors, are proteins that play a crucial role in controlling gene expression by switching genes on and off.

Transcription regulators bind to specific DNA sequences in the regulatory regions of genes, modulating the initiation and rate of transcription.

The binding of transcription regulators to DNA can either activate or repress gene expression, depending on the specific regulatory elements and the context of the gene being regulated.

Activator transcription regulators enhance gene expression by recruiting the transcriptional machinery, including RNA polymerase and coactivator proteins, to the gene promoter.

Activators often have activation domains that interact with components of the transcriptional machinery, initiating the assembly of the pre-initiation complex and promoting transcriptional initiation.

Repressor transcription regulators inhibit gene expression by competing with or blocking the binding of activators to the gene promoter or by recruiting corepressor proteins that inhibit transcription.

Repressors often have repressor domains that interact with the transcriptional machinery or chromatin-modifying enzymes, leading to the repression of transcriptional activity.

Transcription regulators can also modulate gene expression by influencing the chromatin structure and accessibility of gene regulatory regions.

Chromatin remodeling complexes, recruited by transcription regulators, can alter the positioning or accessibility of nucleosomes, allowing or restricting the binding of transcriptional machinery.

Transcription regulators can interact with coactivators or corepressors to modify the local chromatin environment through histone modifications or DNA methylation.

Coactivators can mediate the addition of acetyl groups to histones (histone acetylation), which leads to a more open chromatin structure and facilitates transcription.

Corepressors can recruit histone deacetylases or DNA methyltransferases, resulting in the removal of acetyl groups from histones (histone deacetylation) or the addition of methyl groups to DNA (DNA methylation), respectively. This leads to a more compacted chromatin structure and transcriptional repression.

Transcription regulators themselves can be subject to regulation, including post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and intracellular signaling pathways.

Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, or ubiquitination, can alter the activity, stability, or subcellular localization of transcription regulators.

Transcription regulators can interact with other proteins, including coactivators or corepressors, forming complexes that influence their function and specificity.

Intracellular signaling pathways, triggered by extracellular cues or environmental stimuli, can activate or inactivate specific transcription regulators, leading to changes in gene expression.

Transcription regulators can act in a combinatorial and context-dependent manner, where the presence or absence of specific regulators determines the gene expression outcome.

Molecular genetic mechanisms that create and maintain specialized cell types

Cell Differentiation:

- Cell differentiation is the process by which unspecialized cells become specialized and acquire distinct structures and functions.

- It is governed by molecular genetic mechanisms that control gene expression and orchestrate the development of different cell types.

- Key regulatory factors involved in cell differentiation include transcription factors, signaling molecules, epigenetic modifications, and non-coding RNAs.

Transcriptional Regulation:

- Transcription factors play a crucial role in creating and maintaining specialized cell types by controlling the expression of specific genes.

- Different cell types have unique transcription factor profiles, which drive the activation or repression of lineage-specific genes.

- Combinatorial interactions between transcription factors, along with their binding to specific DNA regulatory elements, result in precise control of gene expression.

- Transcription factors can act as activators or repressors, modulating the initiation and rate of transcription to establish cell-specific gene expression patterns.

Signaling Pathways:

- Signaling molecules, such as growth factors and cytokines, provide crucial cues during cell differentiation by activating intracellular signaling pathways.

- These pathways transmit signals from the cell membrane to the nucleus, modulating gene expression and directing cell fate decisions.

- Activation of specific signaling pathways can induce the expression of key transcription factors that drive cell differentiation along specific lineages.

- Notch, Wnt, TGF-beta, and Hedgehog are examples of signaling pathways involved in cell fate determination during development.

Epigenetic Modifications:

- Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling, contribute to the establishment and maintenance of cell identity.

- DNA methylation patterns can be heritable and are involved in gene silencing or activation during development.

- Histone modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, influence chromatin structure and accessibility, impacting gene expression.

- Chromatin remodeling complexes can modulate the positioning and accessibility of nucleosomes, affecting transcription factor binding and gene regulation.

Non-Coding RNAs:

- Non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), play regulatory roles in cell differentiation.

- MicroRNAs can post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), leading to their degradation or inhibition of translation.

- LncRNAs can interact with DNA, RNA, or proteins, modulating gene expression through various mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling or mRNA stability.

Cell-Cell Interactions:

- Cell-cell interactions and communication between neighboring cells also contribute to the creation and maintenance of specialized cell types.

- Signaling molecules, including cell adhesion molecules, growth factors, and morphogens, can be secreted by neighboring cells, influencing gene expression and cell fate decisions.

- Intercellular signaling is vital in establishing tissue architecture and ensuring coordinated differentiation within multicellular organisms.

Feedback Mechanisms:

- Feedback mechanisms help maintain cell identity and prevent the loss of specialized features.

- Transcription factors and signaling pathways involved in cell differentiation can regulate their own expression or repress alternative lineage-specific programs.

- These feedback loops ensure the stability and fidelity of cell types by reinforcing the expression of lineage-specific genes and suppressing alternative developmental programs.

Mechanisms that reinforce cell memory in plants and animals

Epigenetic Modifications:

- Epigenetic modifications play a crucial role in reinforcing cell memory by maintaining stable gene expression patterns across cell divisions.

- DNA methylation is a common epigenetic modification that can be heritable and help maintain cell identity by silencing specific genes.

- Histone modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation, contribute to the establishment and maintenance of specific gene expression patterns.

- Epigenetic marks act as molecular "tags" that can be propagated during DNA replication or cell division, preserving the transcriptional state of genes.

Chromatin Remodeling:

- Chromatin remodeling complexes help reinforce cell memory by maintaining the accessibility and organization of chromatin.

- These complexes can position nucleosomes to create open or closed chromatin configurations, influencing gene accessibility and transcriptional activity.

- ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers use energy from ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or exchange nucleosomes, modulating gene expression states and reinforcing specific transcriptional programs.

Transcriptional Feedback Loops:

- Transcriptional feedback loops involving transcription factors contribute to the reinforcement of cell memory.

- Positive feedback loops involve transcription factors that activate their own expression or the expression of other key regulators, amplifying and maintaining their presence in specific cell types.

- Negative feedback loops involve transcription factors that repress their own expression or the expression of alternative lineage-specific genes, stabilizing cell identity and preventing lineage switching.

Cell-Cell Communication:

- Cell-cell communication plays a role in reinforcing cell memory by providing signals and cues to neighboring cells.

- Signaling molecules, including growth factors and morphogens, can be secreted by cells and influence the gene expression patterns and cell fate decisions of adjacent cells.

- Cell adhesion molecules and cell signaling pathways contribute to maintaining the spatial organization and structural integrity of tissues, reinforcing cell identity.

Environmental Sensing and Response:

- Environmental cues can influence cell memory by modulating gene expression and cellular responses.

- Cells can sense and respond to changes in their microenvironment, adjusting gene expression programs accordingly.

- Environmental signals, such as temperature, light, hormones, and nutrient availability, can trigger signaling pathways and transcriptional changes, reinforcing cell memory in response to specific conditions.

Mitotic Stability:

- Mitotic stability ensures the faithful transmission of cell memory to daughter cells during cell division.

- Epigenetic marks, chromatin structures, and transcription factor profiles are preserved through mitosis, maintaining the transcriptional states and cell identity of progeny cells.

- Mechanisms such as DNA replication timing and mitotic bookmarking help ensure the accurate transmission and maintenance of cell memory during cell division.

Post-Transcriptional controls:

mRNA Processing:

- Alternative splicing: Different combinations of exons within a pre-mRNA can be spliced together, generating multiple mRNA isoforms from a single gene.

- RNA editing: The nucleotide sequence of mRNA can be modified by enzymatic processes, leading to changes in the coding sequence or regulatory regions.

- Polyadenylation: The addition of a poly(A) tail to the 3' end of mRNA stabilizes the molecule, affecting its stability and translation efficiency.

- mRNA capping: The addition of a 5' cap to mRNA protects it from degradation and facilitates translation initiation.

mRNA Stability and Decay:

- mRNA stability is controlled by specific RNA-binding proteins and regulatory sequences within the mRNA molecule.

- mRNA degradation can be initiated by deadenylation, decapping, or exonucleolytic digestion.

- Regulatory elements such as AU-rich elements (AREs) in the mRNA sequence can target it for rapid degradation.

- Conversely, stabilizing factors such as RNA-binding proteins or microRNAs can protect mRNA from degradation.

RNA Localization and Transport:

- Some mRNAs are localized to specific subcellular compartments, allowing for spatial control of protein synthesis.

- RNA-binding proteins and cis-acting elements within the mRNA sequence facilitate its transport to specific cellular locations.

- mRNA localization contributes to the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity and specialized functions.

Translational Control:

- Regulatory elements within the mRNA sequence, including upstream open reading frames (uORFs) and internal ribosome entry sites (IRES), can modulate translation initiation.

- RNA-binding proteins and microRNAs can interact with mRNA and affect translation efficiency by promoting or inhibiting ribosome recruitment.

- Initiation factors and ribosome-associated proteins play a role in translational control by regulating the assembly and activity of the translation machinery.

RNA Interference (RNAi):

- RNAi is a post-transcriptional mechanism that regulates gene expression by using small RNA molecules.

- Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) can bind to mRNA and induce its degradation or inhibit translation.

- The RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) guides the recognition and degradation of target mRNAs based on sequence complementarity.

RNA Modification and Editing:

- RNA molecules can undergo modifications, such as methylation or pseudouridylation, which can affect their stability, localization, or function.

- RNA editing involves the enzymatic alteration of nucleotide sequences within RNA molecules, leading to changes in the encoded protein or regulatory regions.

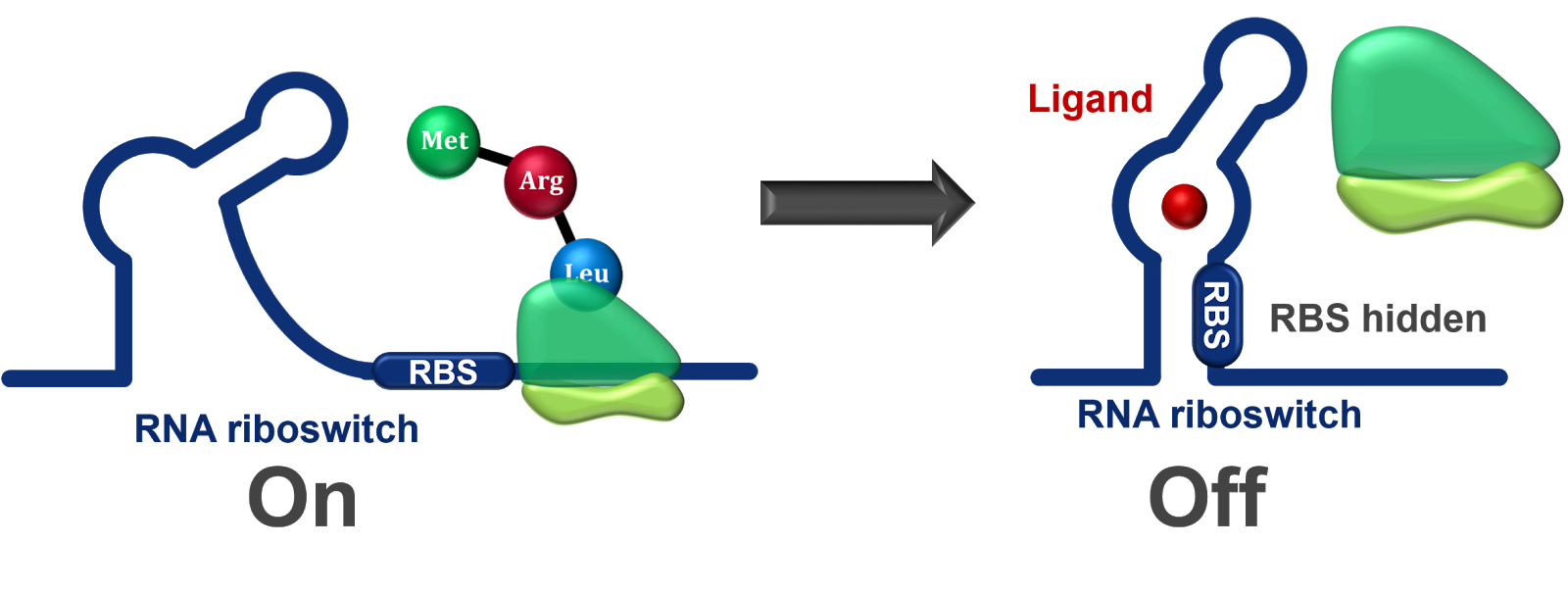

Riboswitches:

Riboswitches are structural elements present within mRNA molecules that can modulate gene expression in response to specific ligands.

Binding of a ligand to the riboswitch can cause structural changes that affect transcription, translation, or mRNA stability.

Protein Synthesis and Degradation:

- The efficiency of protein synthesis and the stability of newly synthesized proteins contribute to post-transcriptional control.

- Chaperones and protein folding machinery ensure the proper folding and stability of newly synthesized proteins.

- Ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy pathways play a role in protein degradation, regulating protein levels and turnover.

Regulation of gene expression by noncoding RNAs:

- Noncoding RNAs are key regulators of gene expression, contributing to diverse biological processes.

- They can modulate gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, influence chromatin structure, and participate in complex regulatory networks.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs):

miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs approximately 21-25 nucleotides in length.

They regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs).

Binding of miRNAs leads to mRNA degradation or translational repression, resulting in reduced protein expression.

miRNAs are involved in various cellular processes, including development, differentiation, and response to environmental stimuli.

Dysregulation of miRNA expression has been implicated in diseases such as cancer and neurological disorders.

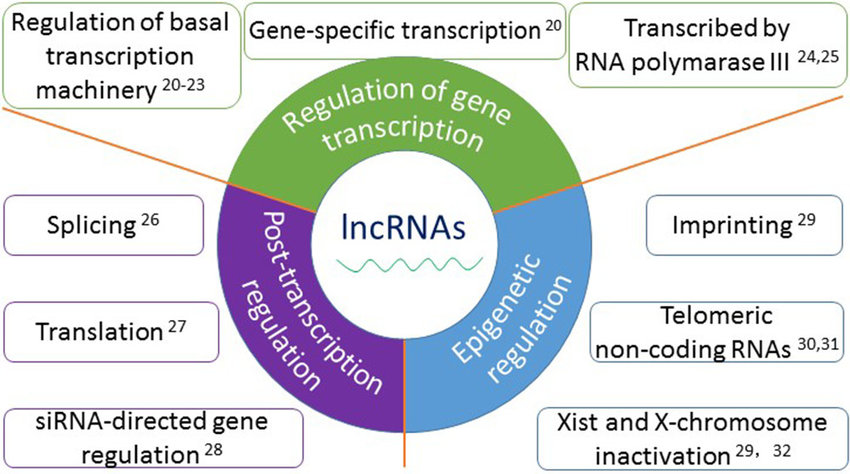

Long Noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs):

lncRNAs are RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding capacity.

They can be transcribed from intergenic regions, introns, or antisense strands of protein-coding genes.

lncRNAs exhibit diverse mechanisms of action, including regulation of transcription, chromatin remodeling, and modulation of RNA processing.

They can act as molecular scaffolds, interacting with DNA, RNA, and proteins to form ribonucleoprotein complexes.

lncRNAs play critical roles in cellular processes, such as X chromosome inactivation, imprinting, and development.

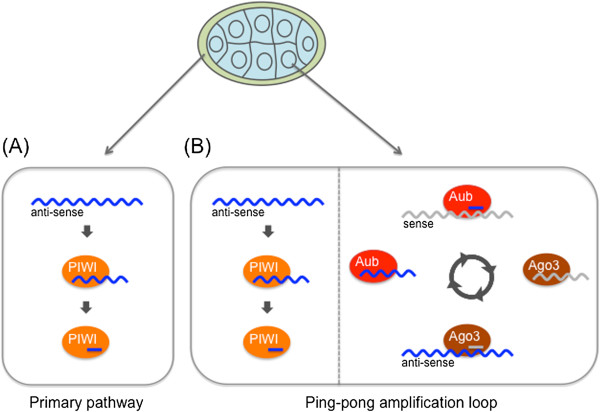

Piwi-Interacting RNAs (piRNAs):

piRNAs are a class of small noncoding RNAs typically 24-32 nucleotides in length.

They interact with Piwi proteins and are involved in silencing transposable elements (TEs) in germ cells.

piRNAs guide Piwi proteins to complementary sequences in TE transcripts, resulting in their degradation or transcriptional silencing.

This mechanism helps maintain genome integrity and prevent transposon activation in germ cells.

Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs):

- siRNAs are double-stranded RNA molecules typically 20-25 nucleotides in length.

- They are produced from long double-stranded RNA precursors or from exogenous sources, such as viral RNA.

- siRNAs are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and guide RISC to complementary mRNA sequences.

- Binding of siRNAs leads to mRNA cleavage or translational repression, resulting in gene silencing.

- siRNAs are widely used as research tools and have therapeutic potential for gene silencing-based therapies.

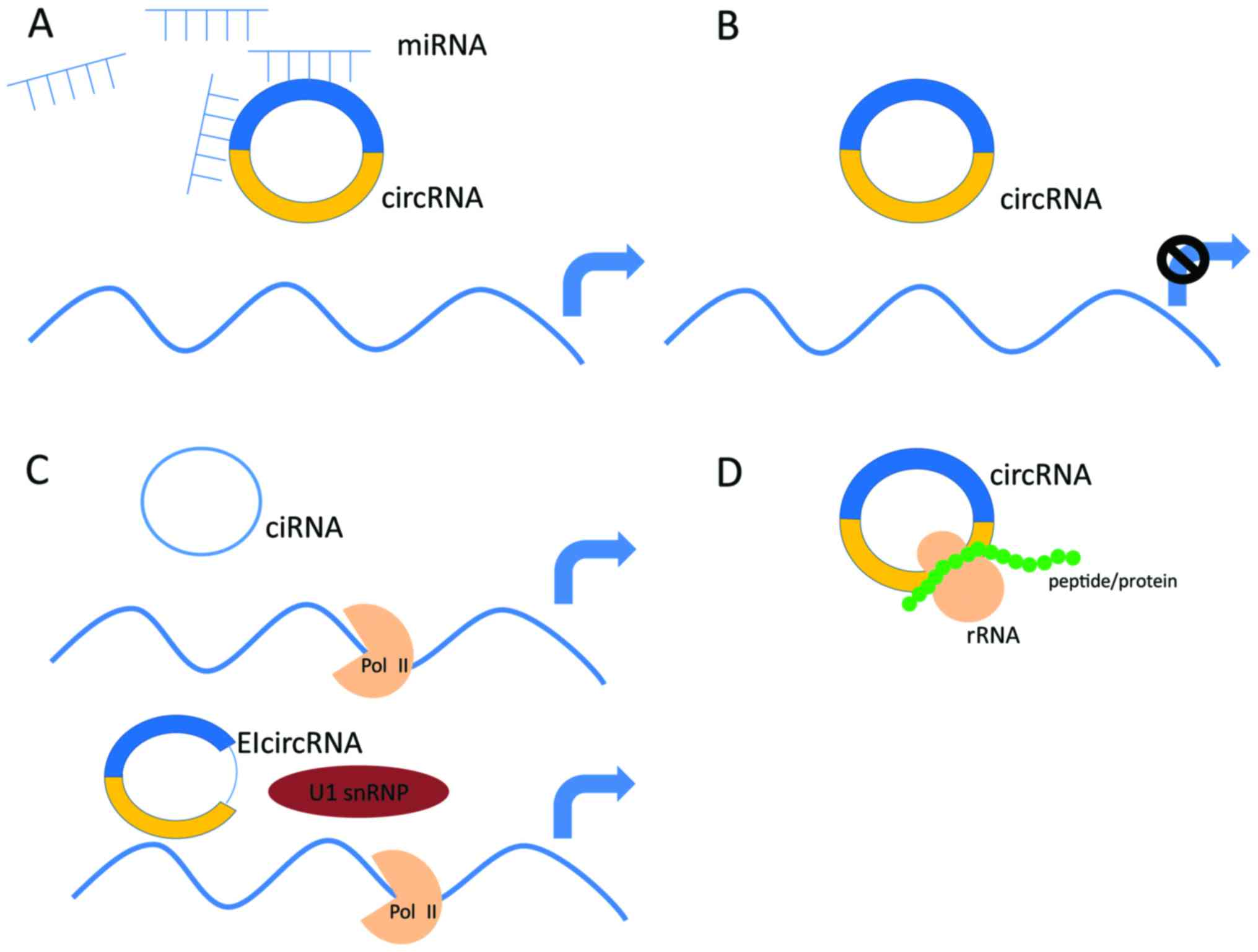

Circular RNAs (circRNAs):

circRNAs are covalently closed RNA molecules formed by back-splicing, where a downstream splice donor site joins with an upstream splice acceptor site.

They are highly stable and resistant to degradation by RNA exonucleases.

circRNAs can act as miRNA sponges, sequestering miRNAs and preventing their binding to target mRNAs.

They can also interact with RNA-binding proteins and modulate their activity.

circRNAs are involved in gene regulation and have been implicated in various diseases, including cancer and neurological disorders.

Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs):

eRNAs are noncoding RNAs transcribed from enhancer regions of the genome.

They are typically short-lived and have low abundance.

eRNAs are thought to play a role in enhancer function, contributing to the regulation of nearby genes.

They can interact with transcription factors and chromatin-modifying complexes, influencing gene expression.