UNIT 1 Chapter 1 & 2, Chemistry

1A ~ Atoms and Elements

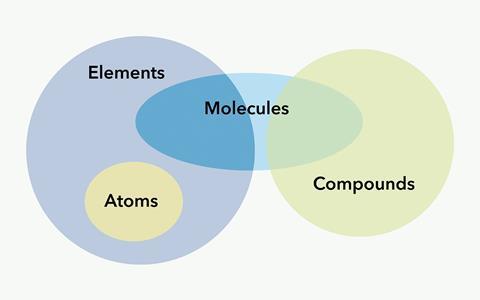

Atoms: The basic unit of a chemical element, consisting of a nucleus surrounded by electrons.

Elements: Pure substances made of only one type of atom, distinguished by the number of protons in their nuclei, known as the atomic number.

Key Terminology:

Atomic Number: The number of protons in an atom's nucleus, which determines the chemical properties of the element.

Mass Number: The total number of protons and neutrons in an atom's nucleus, indicating its overall mass.

Isotopes: Variants of an element that have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons, leading to different mass numbers.

Molecule: A group of two or more atoms bonded together, can be of the same or different elements.

Compound: A substance formed when two or more different elements are chemically bonded together.

1B and 1C - Periodic Table

Atomic Radius

Definition: The atomic radius is the distance from the nucleus of an atom to the outermost shell of electrons.

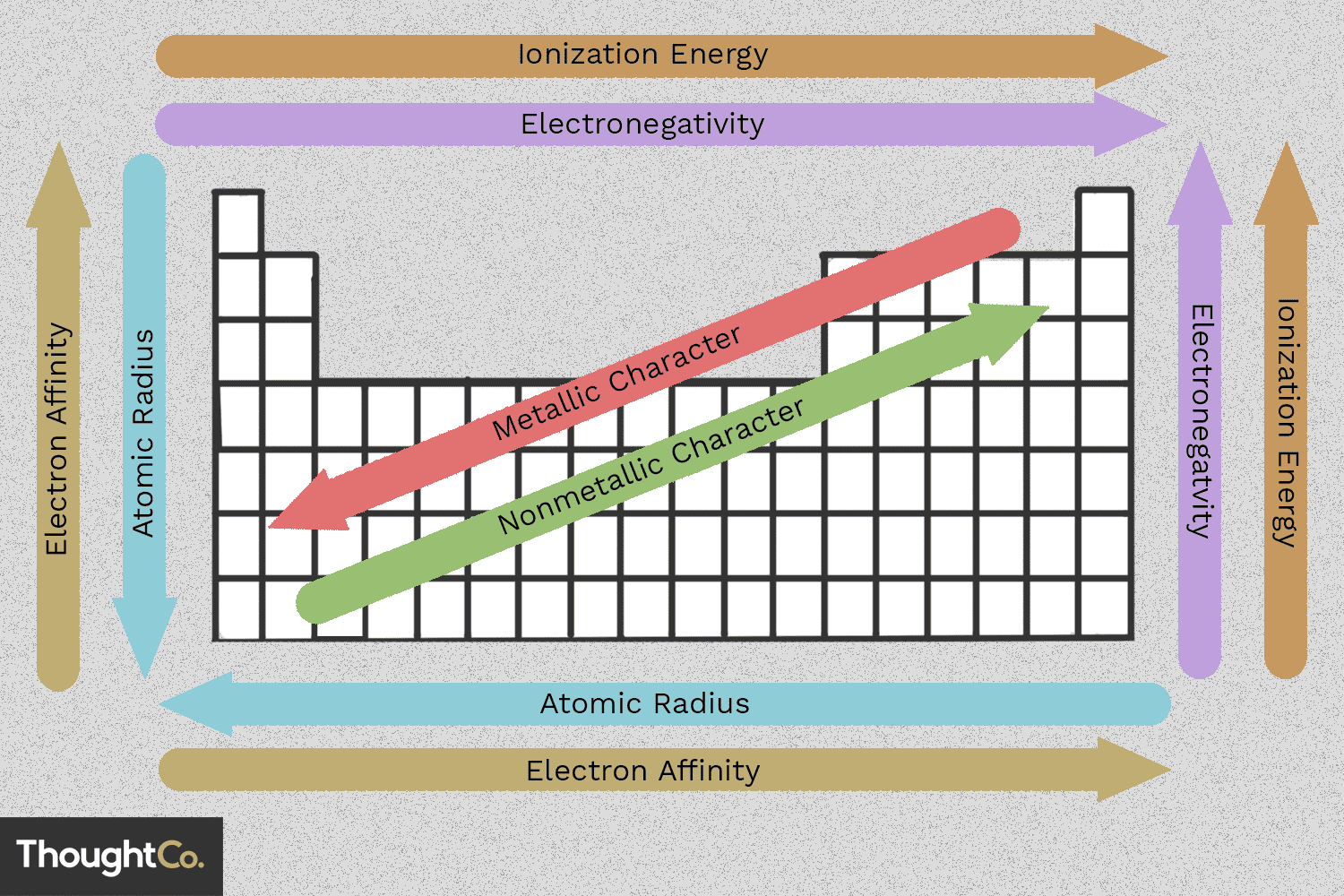

Trend: Atomic radius increases down a group due to the addition of electron shells, which outweighs the increase in nuclear charge. It decreases across a period from left to right as the increasing nuclear charge pulls the electrons closer to the nucleus.

Example:

Largest atomic radius in Group 1 (e.g., Lithium, Na) and smallest in Group 18 (e.g., Neon).

Electronegativity

Definition: Electronegativity is the tendency of an atom to attract electrons in a chemical bond.

Trend: Electronegativity increases across a period due to increased nuclear charge attracting bonding pairs of electrons. It decreases down a group because added shells distance the valence electrons from the nucleus and increase electron shielding.

Example:

Fluorine has the highest electronegativity, while Francium has one of the lowest.

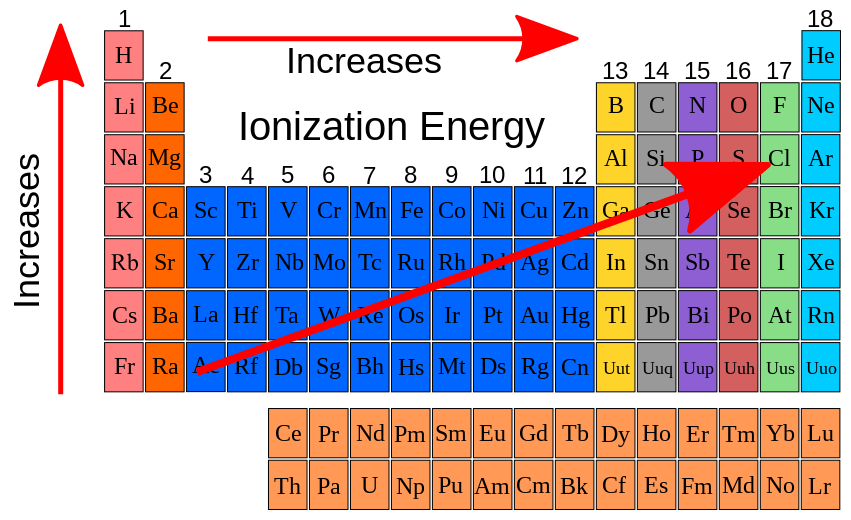

First Ionisation Energy

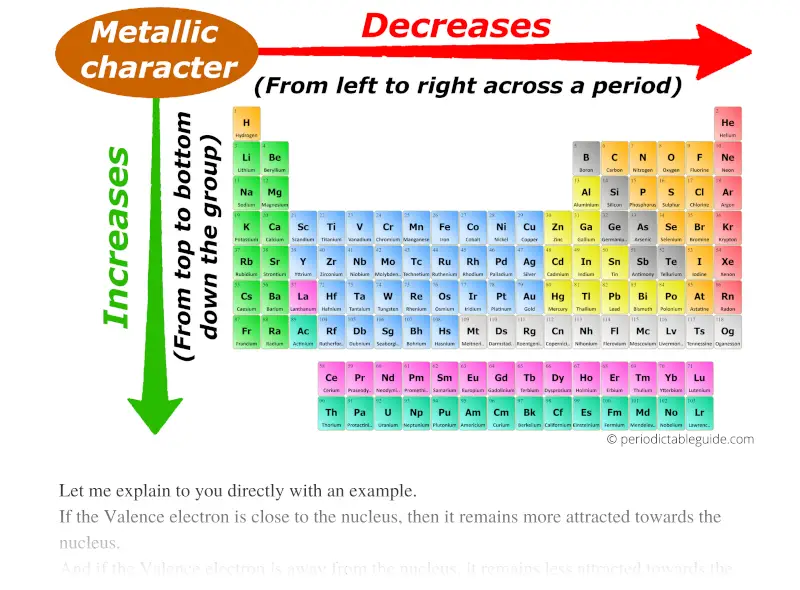

Metallic Character

Definition: Metallic character refers to the tendency of an element to exhibit properties of metals, such as malleability, ductility, and electrical conductivity.

Trend: Metallic character increases down a group and decreases across a period. This is because elements on the left are metals and are more likely to lose electrons compared to non-metals on the right.

Example:

Alkali metals (Group 1) exhibit high metallic character, whereas noble gases (Group 18) exhibit none.

Chemical Reactivity

Definition: Chemical reactivity is the tendency of an element to engage in chemical reactions.

Trend for Metals: Reactivity of metals generally increases down a group, as it is easier for them to lose electrons.

Trend for Nonmetals: Reactivity of nonmetals generally increases up a group, as they more readily gain electrons.

Example:

Sodium (Na) is more reactive than Lithium (Li) as you move down the group, while Fluorine (F) is more reactive than Chlorine (Cl) among nonmetals.

Core Charge

Definition: The core charge is the effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons, calculated as the number of protons minus the inner shell electrons.

Trend: Core charge increases across a period as more protons are added but remains relatively constant down a group as additional electron shells diminish the effect of increased protons on valence electrons.

Example:

Core charge of Sodium (Na) is +1, while for Fluorine (F) it is +7, indicating the stronger pull from the nucleus on its valence electrons compared to Na.

All Trends

SPDF blocks

SPDF Blocks Overview: The periodic table is divided into four blocks based on the filling of electron orbitals: s, p, d, and f blocks.

Key Terminology

Orbitals: Orbitals are spaces around an atom's nucleus where electrons are likely to be found. Each orbital can hold up to two electrons and has a specific shape.

Subshells: Subshells are parts of electron shells. They are identified by letters (s, p, d, f) and contain orbitals that possess similar energy levels, affecting how elements react chemically.

Shells: Shells are layers around an atomic nucleus, defined by the principal quantum number (n). Each shell can contain several subshells based on its number, with the first shell (n=1) having one subshell (1s), the second shell (n=2) having two (2s, 2p), and so forth.

Types of Orbitals

s Orbitals

Shape: Spherical

Maximum Electrons: 2

Sub-shells: Found in all principal energy levels (n=1, 2, 3,...)

p Orbitals

Shape: Dumbbell-shaped

Maximum Electrons: 6 (2 per each of the 3 p orbitals)

Sub-shells: Start from principal energy level n=2

d Orbitals

Shape: More complex (cloverleaf)

Maximum Electrons: 10 (2 per each of the 5 d orbitals)

Sub shells: Start from principal energy level n=3

f Orbitals

Shape: Even more complex

Maximum Electrons: 14 (2 per each of the 7 f orbitals)

Sub-shells: Start from principal energy level n=4)

Summary

Understanding orbitals and subshells is essential in predicting how electrons are arranged in atoms and how they participate in chemical bonding. This knowledge helps explain the properties of elements and their chemical behavior.

The organization into SPDF blocks helps predict element behavior and trends based on their electron configurations.

1D ~ Critical Elements

Definition:

Critical elements refer to key elements essential for specific scientific processes or systems, often used in the context of sustainability, technology, and health.

Key Elements:

These can include elements such as Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N), Oxygen (O), Phosphorus (P), and Sulfur (S), which are vital for biological processes, or elements like Lithium (Li) and Cobalt (Co) important for batteries and electronics.

Importance:

Carbon is fundamental to all organic compounds.

Nitrogen is critical for amino acids and nucleotides.

Oxygen is essential for respiration in most organisms.

Phosphorus is key in energy transfer (ATP) and nucleic acids.

Sulfur plays a role in proteins and vitamins.

Lithium and Cobalt are pivotal in advancements in energy storage technologies, particularly for electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

Sustainability Considerations:

The extraction and use of these critical elements must be managed sustainably to prevent environmental degradation and resource depletion.

Chapter 2: Covalent Substances

Key Concepts

Covalent Bonding: Involves sharing of electron pairs between non-metal atoms. The number of shared pairs defines the type of bond:

Single Bond: One pair shared (e.g., H-H).

Double Bond: Two pairs shared (e.g., O=O).

Triple Bond: Three pairs shared (e.g., N≡N).

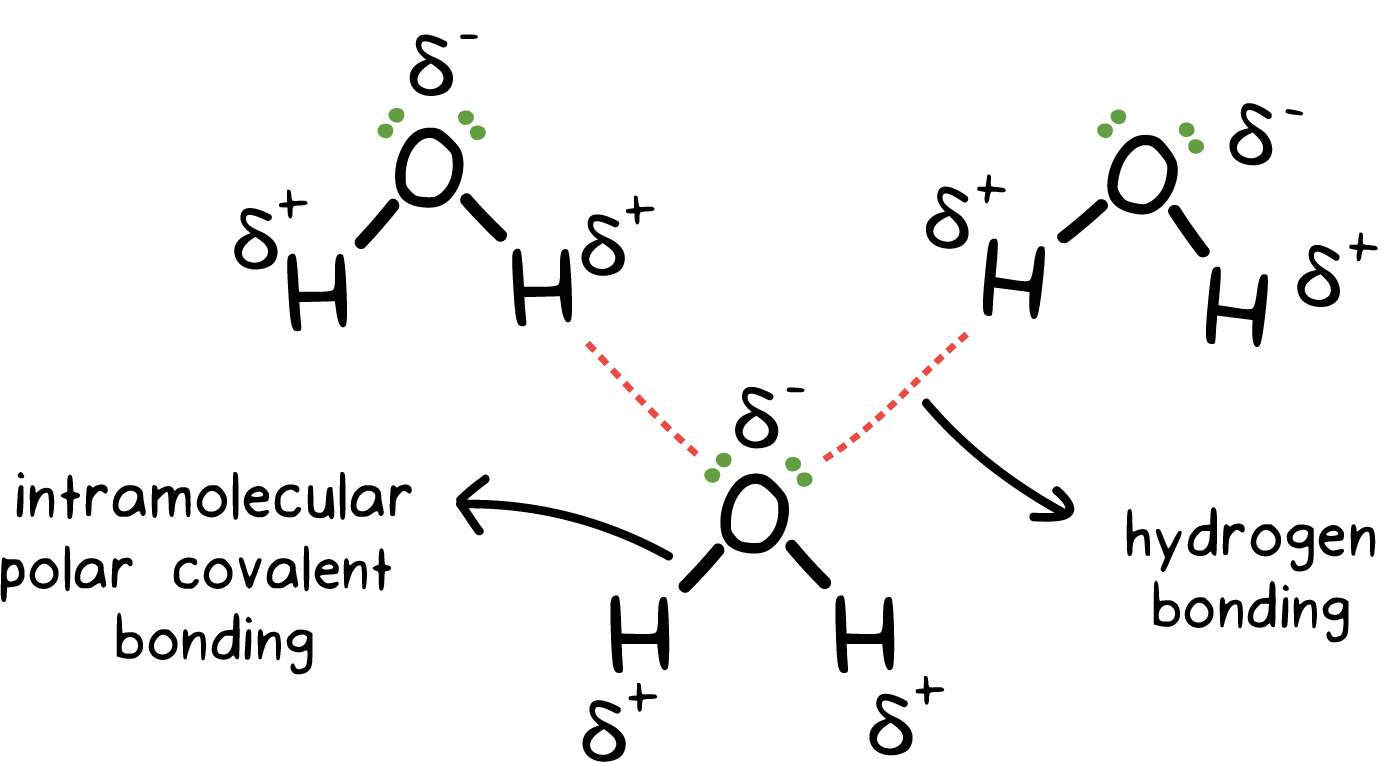

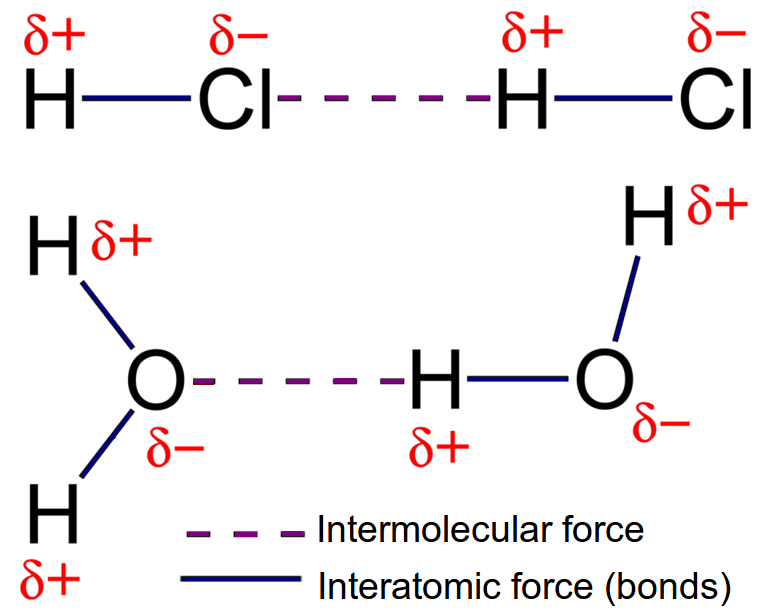

Intramolecular vs Intermolecular Forces: Intramolecular forces are the bonds within a molecule, whereas intermolecular forces are the attractions between different molecules.

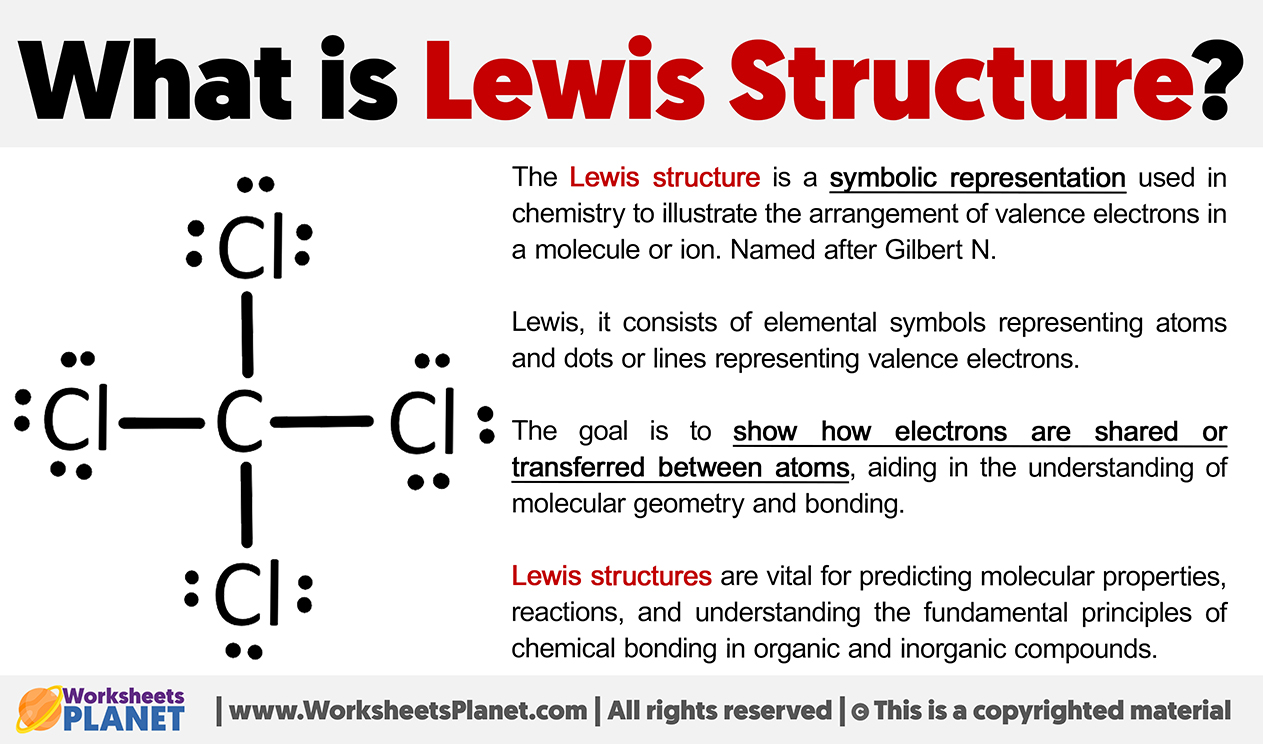

Molecular Representation: Models such as Lewis structures, structural formulas, and molecular formulas represent covalent substances with varying details about the arrangement and

connectivity of atoms.

2A ~ Covalent Bonding

Utilise Lewis structures and molecular formulas:

Water (H₂O): Lewis structure shows oxygen with two hydrogen atoms and two lone pairs. Molecular formula = H₂O.

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂): Linear molecule with a double bond between carbon and each oxygen. Molecular formula = CO₂.

Definition: VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory is a model used to predict the shape of molecules based on the idea that electron pairs around a central atom will arrange themselves as far apart as possible to minimize repulsion.

VSEPR

Electron Pairs: The theory considers both bonding pairs (shared electrons) and lone pairs (non-bonding electrons) of electrons around the central atom.

Repulsion: Lone pairs exert more repulsion on adjacent bonding pairs, affecting the overall shape of the molecule.

Molecular Shapes

Linear (180°)

Example: CO₂ (Carbon Dioxide)

Description: Two bonding pairs with no lone pairs lead to a straight line formation.

Trigonal Planar (120°)

Example: BF₃ (Boron Trifluoride)

Description: Three bonding pairs in the same plane with no lone pairs result in a triangular shape.

Tetrahedral (109.5°)

Example: CH₄ (Methane)

Description: Four bonding pairs spread out in three-dimensional space form a shape like a pyramid with a triangular base.

Trigonal Pyramidal (around 107°)

Example: NH₃ (Ammonia)

Description: Three bonding pairs and one lone pair create a pyramid-like shape with the lone pair pushing the bonding pairs closer together.

Bent (around 104.5°)

Example: H₂O (Water)

Description: Two bonding pairs and two lone pairs create a V-shaped angle due to repulsion from the lone pairs.

Trigonal Bipyramidal (90° and 120°)

Example: PCl₅ (Phosphorus Pentachloride)

Description: Five bonding pairs arranged in a double pyramidal shape, with three pairs equatorial and two axial.

Octahedral (90°)

Example: SF₆ (Sulfur Hexafluoride)

Description: Six bonding pairs arranged symmetrically around the central atom, resembling two pyramids placed base to base.

Square Pyramidal (around 90°)

Example: BrF₅ (Bromine Pentafluoride)

Description: Five bonding pairs and one lone pair lead to a pyramid shape with a square base.

Square Planar (90°)

Example: XeF₄ (Xenon Tetrafluoride)

Description: Four bonding pairs and two lone pairs arranged octahedrally, eliminating axial lone pair repulsion, resulting in a square shape.

Molecular Polarity

Definition: Molecular polarity refers to the distribution of electrical charge across a molecule, which determines how molecules interact with each other. Molecules can be classified as polar or non-polar based on the shape and electronegativity of their atoms.

Polar Molecules

Example: Water (H₂O)

Shape: Bent

Explanation: Water is polar because it has a bent molecular geometry, which creates a difference in charge distribution. The oxygen atom is more electronegative than the hydrogen atoms, resulting in partial negative charges on oxygen and partial positive charges on each hydrogen. The bent shape prevents symmetrical cancellation of dipoles, leading to an overall polar molecule.

Non-Polar Molecules

Example: Carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄)

Shape: Symmetrical Tetrahedral

Explanation: CCl₄ is non-polar because it features a symmetrical tetrahedral shape. Although the C–Cl bonds are polar individually due to the electronegativity difference between carbon and chlorine, the symmetrical arrangement causes the dipoles to cancel each other out, resulting in no overall polarity.

Non-Polar Example: Carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄) is non-polar due to its symmetrical tetrahedral shape, canceling out dipoles.

Intra vs Intermolecular Forces

Differentiate between intramolecular and intermolecular forces: In H₂O, the intramolecular covalent bonds are strong, while the hydrogen bonds between water molecules (intermolecular forces) are comparatively weaker.

Describe the physical properties of molecular substances:

Boiling and Melting Points: Water has a high boiling point (100°C) due to strong hydrogen bonds compared to methane, which has a lower boiling point (-161.5°C).

Electrical Conductivity: Molecular substances like sugar (C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁) do not conduct electricity in solid form, whereas ionic compounds like NaCl, when dissolved in water, can conduct electricity due to free-moving ions.

2B ~ Intramolecular Bonding and Intermolecular Forces

Intramolecular Forces:

These are responsible for holding the atoms together within a molecule. The main types include:

Covalent Bonds: When two non-metal atoms share electron pairs (e.g., O₂ has a double bond).

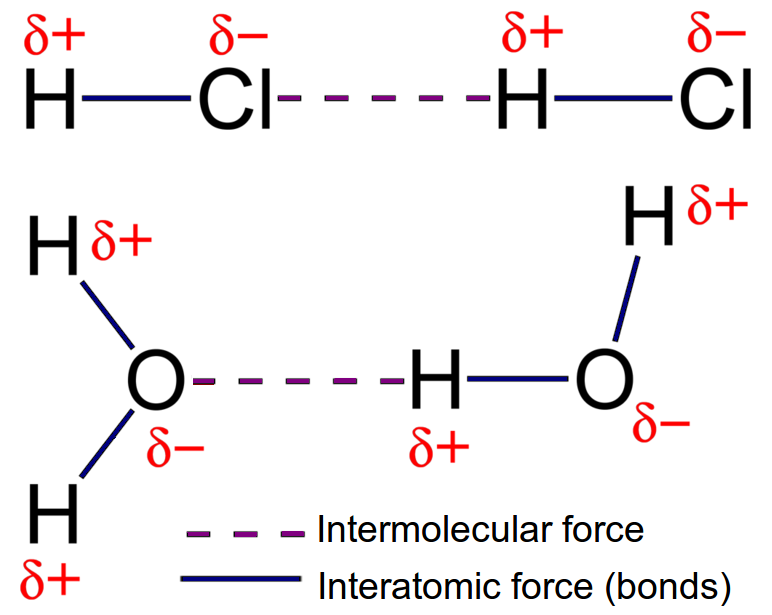

Polar Covalent Bonds: In HCl, chlorine is more electronegative than hydrogen, leading to unequal electron sharing and a dipole.

Bond Pair and Lone Pair:

Bond Pair: In H₂O, there are four pairs of valence electrons around the oxygen atom - two are bond pairs and two are lone pairs.

Intermolecular Forces:

These forces occur between molecules and are responsible for determining the physical properties of substances:

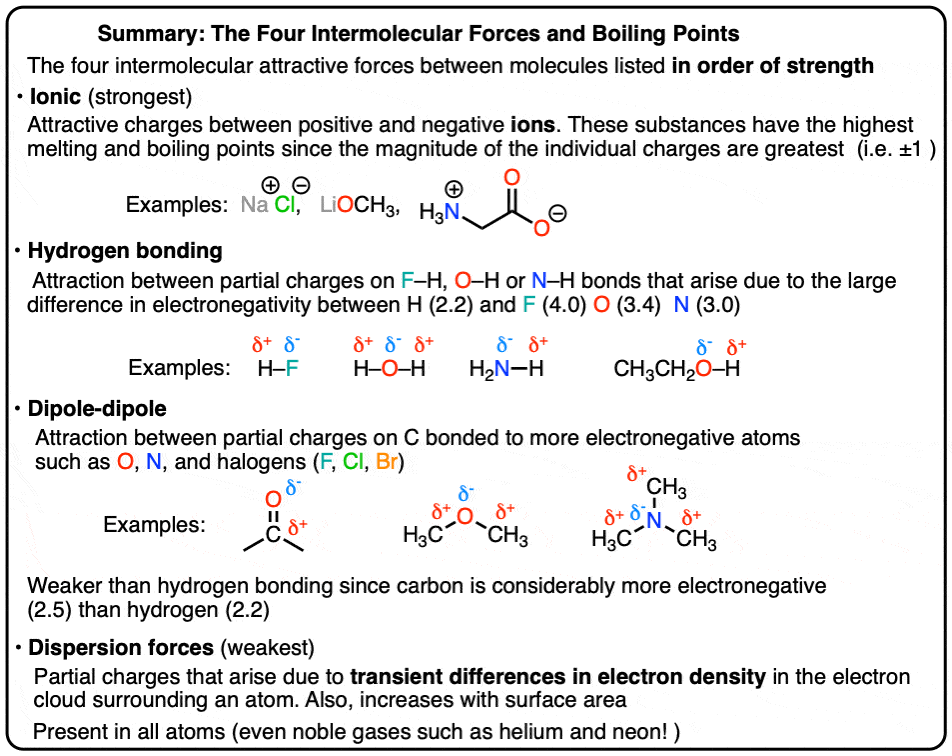

Dispersion Forces (London Dispersion Forces): Present in all molecules, these are the weakest intermolecular forces arising from temporary electron distributions (e.g., noble gases like Ar).

Dipole-Dipole Forces: Occurs in polar molecules; for example, in hydrogen chloride (HCl), the positive end of one molecule attracts the negative end of another.

Hydrogen Bonding: A specific strong type of dipole-dipole interaction, crucial for the properties of water and biological molecules. For instance, in DNA, hydrogen bonds between base pairs maintain the structure of the double helix.

2C: Comparisons of Properties

Relation of Bonding Properties to Diamonds, Graphite, and Carbon

Diamond:

Structure: Diamond has a tetrahedral structure where each carbon atom is covalently bonded to four other carbon atoms, forming a 3D network.

Bonding Characteristics: The carbon atoms in diamond are linked by strong covalent bonds, creating a rigid structure that leads to exceptional hardness. The strength of these bonds is due to the sp³ hybridization of carbon, which allows maximum overlap of orbitals.

Properties: The covalent bonding and the close-packed tetrahedral arrangement contribute to high boiling and melting points. Diamonds do not conduct electricity due to the lack of free-moving electrons, locked in the rigid structure.

Graphite:

Structure: Graphite consists of layers of carbon atoms arranged in hexagonal arrangements, with each carbon atom bonded to three others using sp² hybridization. These layers are held together by weaker van der Waals forces, which allows them to slide over each other easily.

Bonding Characteristics: The presence of delocalized electrons (due to the pi bonds from unhybridized p orbitals) allows graphite to conduct electricity along the planes of carbon atoms, making it a useful material in electrodes. This layered structure facilitates electrical conductivity, differing significantly from diamond.

Properties: Due to the weaker intermolecular forces between layers, graphite has a lower density and is a good lubricant.

Carbon (General):

Allotropes of Carbon: Carbon exists in several allotropes including diamond, graphite, and fullerenes. Each allotrope has unique properties based on its crystalline structure and types of bonding.

Covalent Bonding: The strength and type of covalent bonds (single, double, triple) influence the physical and chemical properties of carbon compounds. For example, in organic compounds, the formation of double bonds contributes to reactivity and the existence of functional groups.

Applications: Understanding these properties is crucial for its applications in materials science, electronics, and as a basis for organic chemistry.

Key Terms

Allotropes:

Different forms of the same element.

Example: Diamond and graphite are both forms of carbon.

Covalent Lattice:

A strong, 3D structure of atoms bonded together by covalent bonds.

Example: The structure of diamond.

Covalent Layer Lattice:

Layers of atoms bonded by covalent bonds, held together loosely.

Example: Graphite, where layers can slide over each other.

Covalent Network Lattice:

A strong structure where atoms are interconnected by covalent bonds throughout.

Example: Silicon carbide and diamond.

Tetrahedral:

Shape with one central atom and four surrounding atoms.

Example: Methane (CH₄).

Trigonal Pyramidal:

Shape with one central atom, three surrounding atoms, and one lone pair.

Example: Ammonia (NH₃).

Delocalized Electrons:

Electrons that can move freely across multiple atoms.

Example: Found in materials like graphite