Property 2

Week one: The concept and purpose of Property

Introduction:

In week 1 we examine the concept and purpose of property. In relation to concepts of property – we consider the legal definition of property, as well as the definition of property in time and space – as things with physical boundaries, and classifications of property as ‘real’ and ‘personal’. We also consider the purpose of property – including theoretical foundations for private property and counter – traditions of property, as well as how new forms of property may be recognised by Australian courts and Parliament.

Property forms a central part of Australian society. People will commonly refer to an item or thing, be it personal property or land, as their property, for example: my book or your house. However, the legal position concerning the status of property is far more complex.

Property is about the relationship between a person and the thing and is how people can enforce rights over certain things. For example

· How far can that individual go in prohibiting or allowing access to that thing?

· When can the thing be sold?

· When can the thing be transferred?

· What can a person do with property?

1.1 What is property?

Property is concerned with the relationship of individuals to things and the extent of that person’s rights or obligations in respect of enforcement.

· How do you currently understand the term “property”?

· What does it mean to have “property” in something?

According to many scholars, the problem with analysing property rights is the lack of a coherent definition of “property”. Consider these uses of the term:

- “Property” describes the relationship between a person has with something they own

- “Property” describes physical things (EG: Land)

- “Property” describes the rights to enforce a contract (EG: bank account)

1.2 Classifications of property rights

The main divisions of property are between real property, personal property and intellectual property. Property can also be divided between ‘private property’ and ‘public’ or ‘common’ property.

· ‘Real property’ refers generally to land

· ‘personal property’ refers to ‘chattels’, that is, property which is not land including objects and other property such as shares and choses in action. Personal property is divided between chattels real (historical categorization for leasehold interests – which are now considered proprietary despite this) and chattels personal (all other personal property)

· ‘intellectual property’ refers to intellectual ‘creations’ such as certain ideas and artistic works protected by law. Intellectual property will not be studied in this unit.

· ‘Private property’ refers to property owned by private individual’s corporations, or other legal entities capable of owning property.

· ‘Public property’ or property known as ‘commons’ (e.g., global commons) refers to property owned by the state (government) or by everyone collectively, e.g., rivers, minerals, Antarctica, the Moon.

In Property Law, chattels refer to personal property (as opposed to real property like land). Chattels are divided into two categories:

1. Chattels Real

- These are personal property with characteristics of real property because they are connected to land but are still considered property. They usually involve a legal interest in land but do not constitute ownership. Examples include:

- Leasehold estates (e.g., a tenant’s rights under a lease)

- Mortgages (interest in land that can be assigned)

Although they relate to real property, they are classified as personal property because they do not grant outright ownership of land – only an interest in it.

2. Chattels personal

- These are purely movable personal property that have no connection to land. They are further divided into

- Choses in possession – Tangible, physical objects (e.g., furniture, cares, jewellery)

- Choses in action – intangible rights enforceable through legal action (e.g., debts, shares, intellectual property)

Key differences:

- Chattels real involve an interest in land (e.g., leases) while

- Chattels personal are separate from land (e.g., physical goods or intangible rights)

Classifications and theories of property | Property can be identified as relating to and depending upon a particular thing (rights in rem)

Usually include · The right to use and enjoy · The right to exclude others · The rights to transfer · The right to possess · The right to destroy

Property often called a ‘bundle of rights’ and is a good working definition of what it means to have property in a thing: - Subject of property: the entity exercising rights over the ‘thing’ - Object of property: the ‘thing’ over which rights are exercised Both are determined in light of social values, as recognised by the state. |

Classifications and theories of property | · Property is a social institution, being a means by which societies regulate access to material resources (power and control) · Counter traditions to these rights include inherent social obligations, duties, and responsibilities to care and tend to land:

- Millrrpum v Mabalco and Western Australian v Ward reflecting spiritual connection of Indigenous people with the land - Protection of the ‘global commons’: (Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons) - Property serves social objectives (France-Hudson)

In the case of Yanner v Eaton, Gleeson, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ said:

‘the word “property” is often used to refer to something that belongs to another. But the Fauna Acts as elsewhere in the law, “Property” does not refer to a thing, it is a description of a legal relationship with a thing. It refers to a degree of power that is recognised in law as power permissibly exercised over the thing.

|

1.3 Defining property: proprietary versus personal (contractual interests)

While many property interests are created pursuant to a contract, not all contractual relations confer a property interest. According to privity of contract, personal rights are only enforceable between contracting parties, which distinguishes them from proprietary rights, however, can be enforced against the whole world. For example:

- You may have permission to enter onto someone’s land but not have any property rights in relation to that land

- A person is lodging in another person’s house pursuant to a contractual relationship which does not confer a leasehold interest but just a contractual licence (note retirement villages here)

Defining property: proprietary versus personal | The fundamental difference between contracts that confer property rights and contracts that do not are that proprietary rights are enforceable against the whole world (rights in rem), whereas contractual rights are enforceable only against the parties to the contract (pursuant to the doctrine of privity of contract) In other words, a person with a contractual right only generally has the right to enforce the contract against the other contracting party and not against third parties.

Distinguish different kind of licences · Bare licence (permission) · Contractual licence · Licence coupled with a proprietary interest

- King v David Allen and Sons Billposting Ltd [1916] 2 AC 54. - Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd (1936) 56 CLR 605. |

King v David Allen and Sons Billposting Ltd [1916] 2 AC 54 | · King entered a licence with David Allen prohibiting adverts posted on walls, King later leased land to Flinn, who wanted to post adverts · Privy council: Agreement between King and David Allen was contractual. Enforceable only against contract parties (not Finn) unless formally assigned. By granting exclusive possession of land to Finn under lease and without assigning the restriction, King was not in the position to fulfil the contract: could not stop Finn posting adverts; liable to David Allen for damages for breach of contract · Question arose as to whether a licence to place an advertisement on the walls of a building given by the preceding tenant bound the new tenant Held · The licence was not binding on the new tenant.

|

King v David Allen and Sons Billposting Ltd [1916] 2 AC 54

Key point | Contractual licences are not proprietary in nature. Earl Loreburn stated the licence does not create any interest in the land expect for a promise to allow the other party to the contract to use the wall from advertising purposes and an implied undertaking that not to breach the contract.

|

1.4 Defining property: horizontal and vertical boundaries of real property

Vertical and horizontal boundaries | While property rights can be distinguished at a theoretical level from person (contractual) rights, real property can also be distinguished physically – through vertical and horizontal boundaries, that establish the end of one person’s ownership, and the start of another’s. Boundaries between parcels or land are shown in survey/title plans and/or a plan of subdivision that accompanies the certificate of title. |

Water course boundaries | Land may be bound by a creek, river, lake, or sea. Where land is bounded by water on one or more sides, the natural process of erosion may reduce or increase the total area of that land. This is known as the doctrine of erosion and accretion and the ownership of land may chance because of this. |

Boundaries | Before determining whether someone has possessed land adversely or whether something is a fixture, need to understand physical boundaries of land. - Boundaries as to height and depth - Boundaries as to horizontal space - Boundaries with seas, rivers, and lakes - Boundaries can be artificial or natural |

Boundaries (vertical) | Cujus est solum est usque ad coelum et ad inferos - The person who owns the surface of the land also owns both the sky and space above the surface stretching to the limits of the atmosphere and the soil beneath the surface down to the centre of the earth Airspace - Depends on what land is owned – e.g., strata subdivisions - Is it real property which can be conveyed (YES)? - Does the owner of the surface have a sufficient property interest in the airspace to raise a claim of trespass or nuisance (doubt as to legal status) Below ground - 8th August 1891 – Limit 50 ft/15.24m - 3rd July 1973 – 15.24m - However, there was always exceptions |

Boundaries (Horizontal) | · Most parcels of land in Victoria are based on survey having derived from a crown grant. The boundaries of which were surveyed and marked on the ground. · The land conveyed in a crown grant is deemed to be the land within the survey boundary (PLA s 269) - PLA s 272 applies the ‘little more a little less’ rule to allow for minor errors in description of boundaries to limit court actions - Fences Act (Vic) s 30E: circumstances in which a person can claim adverse possession regarding boundaries - Fences Act (Vic) s 35: a fence erected on a line that is not the common boundary (water way or other obstruction) does not create adverse possession, or affect the title to or possession of, the adjoining land. |

Watercourse boundaries | · Horizontal boundaries may be fully dimensioned (‘metes and bounds’) or may be defined by reference to a watercourse or the coastline · Boundaries may move as the water level changes under common law doctrine: - ‘erosion’ natural process of erosion or encroachment of the water to reduce the total are of the land - ‘accretion’ natural process of silt deposit (etc) receding water, can increase the total area of that land. · Boundaries with sea and tidal rovers set at the mean high-water mark. The soil below that belongs to the crown. · Rivers, creeks, streams, watercourse, lakes, lagoons, swamps or marshes (i.e., “watercourses”) through private land belong to landowners (Land Act 1958 (Vic) s 384) · If land bounded by a “watercourse” – Land Act (VIC) s 385 |

1.5 Defining property as personal or real: common law

Under the PLA’s s 18, land Is defined to include ‘corporeal hereditaments’, being tangible items capable of inheritance. Personal goods and chattels may become part of land if they are affixed to it in certain ways. Determining whether a chattel has become part of the real property is important in numerous situations; including when land is sold or transferred by gift, is leases, or mortgaged. It is also relevant when a landowner dies. To determine whether an item is a fixture (part of the land) or a chattel (personal property), a court will consider:

1. The contract between the parties

2. The doctrine of fixtures, comprising the (i) degree of annexation and (ii) object of annexation limbs.

Definition: The doctrine of fixtures determines when an item attached to land becomes part of real property (a fixture) rather than remaining personal property (a chattel). Its governed by the principle “quicquid plantatur solo, solo cedit”, meaning “whatever is attached to the soil becomes part of the soil” doctrine is crucial in property law, particularly when resolving disputes in real estate transactions, leases and wills.

1.5 Doctrine of fixtures (common law doctrine) | · Doctrine of Fixtures dictates when items classified as personal property become part of land – so that they change their classification to real property. · Arises from definition of “land” in property Law Act 1958 (Vic) (PLA) s 18 · A physical item capable of being inherited (e.g., goods and chattels) fixed to land becomes part of the land, known as a “fixture” · Pursuant to this doctrine, the owner of land is also the owner fixture to the land The doctrine of fixtures is a legal principle that states that personal property can become real property if it is attached to land. This is important in property law and can affect buyers and sellers in real estate transactions.

How does the doctrine of fixtures apply? - Landlord and Tenant: Tenants can’t install fixtures without the landlord’s consent - Vendor and purchaser: Fixtures are passed to the buyer when land is sold - Mortgagor and mortgage: A mortgagee’s security interest generally includes fixtures - Inheritance: Fixtures automatically pass to those entitled to real estate

How is a fixture determined? The doctrine of fixtures is based on the degree on annexation, or how the item is attached to the land, and the object of annexation, or the intention of the parties. For example, a chandelier bolted to the ceiling is likely a fixture, but a freestanding bookshelf is not. The doctrine of fixtures determines when and in which circumstances an item of personal property which is attached to land loses its identity as a chattel and merges with the land.

What is the impact of fixtures? Fixtures can significantly affect the value and appeal of a property. |

Doctrine of Fixtures Uses/Relevance | Doctrine of fixtures might be relevant when: · Land is sold: Fixtures are passed to the buyer under the contract of sale (chattels will only pass if specifically identified) · Land is mortgaged (or changed): a mortgagee’s security interest will generally include fixtures (but not chattels) · Land is leases to a tenant: special rules apply to fixtures installed by a tenant (common law vs statute) · A landowner dies: fixtures automatically pass to those entitled to the real estate not to those entitled to personal property · Land is given by gift: only fixtures will be passed to the new oner (not chattels) |

Doctrine of Fixtures General Rules | In a dispute about whether an item is part of land, or personal goods, and there is no relevant contract or agreement between the disputing parties, a court will use the doctrine of fixtures to determine the matter. - This requires examining the circumstances that existed at the time the item was annexed (or not) objectively as a question of fact. - The Doctrine has two limbs, which provide structure to your analysis and establish the burden of proof between parties:

- Degree of annexation: How is the item attached to the land? - Object of annexation: What is the item attached to the land and why was it attached?

Criticism of doctrine: - Inflexible, lacking genuine, coherent legal principles (courts take a more holistic approach) - Often overridden by statute in some cases: e.g., in leasing or credit transactions |

1.5 Doctrine of Fixtures: Cases

Belgrave Nominees Pty Ltd v Barlin-Scott Airconditioning (Aust.) Pty Ltd [1984] VR 947 | Facts: - BN was the owner of 2 buildings – BN contracted with a builder to renovate the buildings, including the air conditioning plant. The builder sub-contracted to BSA to supply and fit air conditioning plant (including a chiller) on the roof of each building. BSA positioned a chiller on a custom installed platform constructed on the roof of each building – the chiller stood free on its own weight on Vibersorb pads between its legs and the surface of the planform (shock absorbers). The chillers were connected to the water system by Flanges and Bolts. A water supply pipe was connected to a water pump that was secured on each platform. Electric supply cables forming part of the structure of the building were connected to an electrical junction box fitted to one of the chillers (although not connected to electric power supply. |

BN claimed | BN Claimed relief on the basis that the air-conditioning plant formed part of the building (as a fixture) at the time it was removed, based on the common law that fixing to the property makes them part of the freehold. |

National Australia Bank Ltd v Blacker (2000) 104 FLR 288 | Facts: - Blacker had granted a mortgage to NAB over “mortgaged property” – under the real property mortgage, “mortgaged property” was defined to include a specific parcel of land “farm” and “all plant, machinery and other improvements affixed thereto” (at the time of mortgage or subsequently). blacker wrote to NAB to advice that it would be vacating the premises, (handing the land over to NAB) and identified that they were still using the irrigation system including pumps and sprinklers which “were not fixtures” – and that they would also be removed. In the same letter, Blacker asked whether NAB wishes to purchase the irrigation equipment from them. The day after receiving a holding response from NAB on the issue, Blacker removed the pumps, sprinklers, and valves from the land. - A dispute arose whether the pumps were chattels or fixtures (on the basis that pumps were a party of the underground irrigation system – therefore whether blacker was entitled to remove them. |

Held | Per Conti J: - Establish the objective intention with which the items were put in place [10]. - No one satisfactory test to determine the issue. Common considerations include looking at the degree and object of annexation and all the relevant circumstances. - In some circumstances, a chattel may be a fixture even if not affixed to land, and an object may be a chattel even though affixed to land → use objective test. - Since the items were not fixed into the ground the onus of proof was on NAB to prove that the items were fixtures. ▪ - All could be removed without damaging the land, and the cost of removing them was much less than their value. Thus, all of the items were deemed to be chattels, which entitled the Blackers a right to remove them. - NB: A dairy farm requires an irrigation system, so it is unusual that the court allowed the removal of certain parts of the system → Is the annexation point more important than the purpose point? - NB: The presumptions are rebuttable. They simply allocate the onus of proof. Therefore, NAB had the onus of proving that the pumps and sprinkler-heads were fixtures; and the Blackers had the onus of proving that the valves were chattels

|

1.5 Doctrine of Fixtures: Degree of Annexation | · Mode and structure of annexation: how is the item affixed? · Whether removal would cause damage to - The land or building the item is attached, or - The team itself · Whether it would cost more to remove it than the item is worth |

Presumption and burden of proof | Is the item affixed? - If the item is fixed (other than by its own weight) it is presumed to be a fixture. The burden of proof lies with the party claiming the item is a chattel to prove otherwise. - If the item is not fixed (or only by its own weights) it is presumed to be a chattel. The burden of proof lies with the party claiming the items if a fixture to prove otherwise. Burden of proof difficult to satisfy in our cases examples, cases are lost due to a failure to satisfy the burden of proof rather than won by the parties who have the presumption in their favour |

1.5 Object of annexation: test | Belgrave Nominees, at 951: - Nature of the chattel: what is it? Objectively do you expect it to be a chattel, or does it form part of a building/land? is it essential to the building? is it unique (can it be easily replaced with another)? - The relation and situation of the party making the annexation Vis-à-vis the freehold owner/person in possession: what is the business of the parties? does this affect how you view the item as a chattel or fixture? - The mode of annexation: (degree of annexation considerations) what is the mode of fixing? would removal cause damage to the building (more likely fixture) or item (more likely chattel)? does it cost more to remove the item than the item is worth? is expertise/specialist required to remove the item - Purpose of fixing: does fixing allow item to be enjoyed? or does fixing improve the building/land? us fixing temporary or permanent (mode of fixing might impact this) |

1.5 Object of annexation: Mode of annexation | · Mode and structure of annexation: How is the item affixed? · Whether removal would cause damage to: - The land or buildings to which the item Is attached, or - The item itself · Whether it would cost more to remove it than the item is worth |

1.5 Object of annexation: purpose of fixing | · Whether the article was attached for the better enjoyment of the article, or for the better enjoyment of the land or building to which it was attached, including: - The nature of the property the subject of affixation - Whether the item was to be in position either permanently or temporarily - The purpose of annexing it |

Removal of fixtures | Fixtures attached to land can be removed in certain conditions. A contract between the relevant parties may provide for some items personal property to be removed from the land when, for example, a vendor and purchaser complete settlement of the sale of land, or when a lease expires, and the tenant vacates the property. Where there is not relevant contract between relevant parties, removal may be permitted by statute or common law. |

1.6 New Forms of property

While lawmakers are very reluctant to recognise or develop new forms of property, new forms of property are recognised by judiciary and the legislature from time to time. Example of property that has been recognised over time include Native Title, restrictive covenants interests, intellectual property, human body parts and products, Environmental resources.

1.6 Recognising new forms of property | Common law and equity recognised various categories pursuant to the doctrine of numerus clauses. While the categories of property are not closed, the parliament and judiciary are reluctant to recognise new forms of property outside of these categories.

For example: - Courts have recognised new forms of property to resolve Inequity between parties, recognise input of skills/expertise, promote personal autonomy, reflect changing political and moral values, prevent exploitation, but have difficulty recognising property where rights are hard to identify/articulate For example: Human bodies. body parts, tissue - Parliament has recognised new forms of property to protect, conserve and manage natural recourses, recognise input of skill/expertise For example: Water, Carbon, Fisheries, Intellectual property

New interactions between individuals and ‘things’ challenge the boundaries of property law to expand. While the classes of what is recognised as property are not closed, this does not mean that recognition as property is appropriate in all cases |

Lyria Bennet moses ‘the applicability of property law in new contents to cyberspace’ (2008) 30 (4) SLR 639 | - Courts and commentators struggle to explain limits on what constitutes a ‘thing’ that might be an object of property rights, when the thing arises from technological change - Where change results in some new thing that might be recognised as property, it more than one person could have the rights in it simultaneously there is potential for conflict. - To resolve that conflict should the general rules of property apply, or sui generis right created? - Consider both: The role of property and implications of exclusion and concept of property. - There are physical and conceptual limitations to what can be ‘property’ and this can include the commercial value, as well as moral and practical challenges. - Property law is broad but needs to be varies according to the type of property involved. |

1.6 FOR EXAMPLE: property in environmental recourses | Property used to protect against exploitation, encourage conservation, manage use and access to natural recourses: · Water: Tradeable water permits · Fisheries: fishing quotas based on volume of fish caught/percentage of stock availability · Carbon sequestration (climate chance): rights in carbon sequestration dealt with separately to trees and/or land. Carbon sequestration creates personal ‘carbon credits’ under the Emissions reduction Fund under the carbon credits Act 2011 (Cth) · Environmental protection and biodiversity conservation: Imposition of conservation covenants ‘that can lock in protection or conservation actives indefinitely. |

1.7 Proprietary remedies

Remedies that attach to property rights extent beyond payment of monetary damages, to remedies that can prevent or mandate certain behaviour in relation to land. You will come across two key proprietary remedies in case law: Injunctions and specific performance.

1.7 Proprietary remedies, Property law and remedies | Another feature of property is that the applicable law, that is, property law provides an additional distinct set of remedies that go beyond the traditional remedies of contractual damages, including: - Injunctions - Trespass - Detinue and conversion - Equitable and legal remedies

|

Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd (1937) 56 CLR 605

| Facts: - Rosehill was conducting a race meeting on the land, and in consideration for Cowell paying 4 shillings, allowed Cowell to remain on the racecourse and view the race. Rosehill ejected Cowell from the racecourse before the conclusion of the race. Cowell alleged assault and argues that Rosehill breached its contract with Cowell by ejecting him (Revoking licence). The appellant stated that the respondent was carrying out horseracing on the land and that the respondent had informed him that if the appellant paid to the respondent four shillings, he would be allowed to remain on the property to watch the races. The appellant paid four shillings to the respondent and stated that in seeking to removing from the land the respondent was in breach of the contractual licence that was in place. In other words, it was not possible to revoke a licence which was contractual.

Legal Issue: - The issue in the circumstance was whether a licence which was contractual in nature could be revoked.

Held: - It was held that a licence, although it had been paid for by the appellant did not create any proprietary interest. It did create a contractual right; however, this was revocable at common law and the respondent was not prevented by equity from revoking the licence or relying on the revocation. The result was that the licence was revoked before the alleged assault and therefore, the appellant’s appeal failed.

|

Property law and remedies protection of property | How are property rights protected in Australia? · Australian constitution s 51(xxxi): to “the acquisition of property on just terms from any state or person for any purpose in respect of which the parliament has power to make laws · Land Acquisition and Compensation Act 1986 (Vic) establishes a framework for “compulsory acquisition”. This includes an entitlement to compensation (s 30) · Chater of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) s 20 provides that a person “must not be deprived of his of her property than in accordance with the law”. |

Week one summary and Key points

Week 1 introduces the concept and purpose of property in law. It explores how property is legally defined, categorized, and understood in terms of rights and obligations. Property is not just about ownership of things but about the legal relationship’s individuals have with those things, determining their rights to use, transfer, exclude others, or even destroy property. The classification of property includes real, personal, and intellectual property, as well as distinctions between private and public property.

Theoretical perspectives on property highlight its role as a social institution regulating access to material resources. Property rights are commonly viewed as a ‘bundle of rights,’ but counter-traditions emphasize social obligations, such as Indigenous spiritual connections to land and environmental concerns (e.g., the ‘tragedy of the commons’).

The legal distinction between proprietary rights (which are enforceable against the world) and personal (contractual) rights (which only bind parties to a contract) is explored, with case law illustrating these principles.

The week also examines physical boundaries of property—both vertical (airspace and subsurface) and horizontal (surveyed land boundaries and watercourse boundaries)—and how natural processes like erosion and accretion affect ownership.

Finally, the doctrine of fixtures is introduced, explaining when personal property becomes part of real property due to its attachment to land. This doctrine is crucial in disputes over property ownership and transactions such as sales, leases, mortgages, and inheritance.

Key takeaways

1. Definition | - Property law regulates the use, transfer, and rights associated with land and goods. It includes both real property (land and things attached to it) and personal property (movable items). |

2. Real property | · Real property refers to land and anything permanently attached to it, including buildings, structures and fixtures · Physical boundaries of property: The physical boundaries of property are defined by the land boundaries. In general, property extends from the surface of the land downward to the centre of the earth and upwards to the sky, with some exceptions for air and mineral rights. The boundaries of land are typically marked by fences, walls, or natural landmarks (e.g., rivers) · Land is defined under the Property Law Act 1958 (PLA) s 18 as “corporeal hereditaments”, referring to tangible items capable of inheritance. |

3. Personal property | · Personal property (chattels) includes items such as furniture, goods, and vehicles · Personal goods can become part of land if affixed to it in certain ways, thus becoming fixtures under the Doctrine of Fixtures

|

4. Doctrine of fixtures | · Definition: The doctrine of fixtures dictates when personal property (chattels) becomes part of land, changing its classifications to real property · This applies in situations such as land sales, leases, mortgages, and inheritance How it applies: - Landlord and Tenant: Tenants cannot install fixtures without the landlord’s consent - Vendor and purchaser: Fixtures automatically pass to the buyer in a sale, unless stated otherwise - Mortgage: Mortgages generally include fixtures as part of the security interest - Inheritance: Fixtures pass to those entitled to the real estate - Gift: Only fixtures pass to the new owner, not chattels

|

5. How is a fixture determined | · Degree of Annexation: How the item is attached to the land (e.g., bolted, nailed). · Object of annexation: The purpose and intention behind attaching the item to the land

Examples

Belgrave Nominees Pty Ltd v Barlin-Scott: Court found air conditioning plant wasn’t fixed enough to be a fixture

National Australia Bank Ltd v Blacker: Court ruled irrigation equipment was a chattel, not a fixture, based on the degree of annexation and intended use.

Criticism of doctrine The doctrine is seen as inflexible and often overridden by statute, particularly in leasing or credit transactions. |

6. New form of property | Courts are legislators sometimes recognize new forms or property to address changed in technology, society, and the economy. These include - Intellectual property - Environmental resources (e.g., carbon credits, water, fisheries) - Human body parts Challenges: - Technological advances challenge the traditional boundaries of property law, especially in cyberspace and digital resources - Lyria Bennett Moses discusses challenges in categorizing new forms of property due to technological changes and conflicting interests |

7. Proprietary remedies | Property law provides remedies beyond monetary damages, including: · Injunctions · Trespass · Detinue and conversion · Specific performance Case examples Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd: Court ruled that a paid license to view a race was a contractual right, not a proprietary interest, and thus could be revoked by the property owner

|

8. Protection of property | · Australia constitution s 51(xxxi): Property cannot be acquired by the government or any state without just compensation · Land Acquisition and Compensation Act 1986 (Vic): establishes compensation rights in cases of compulsory property acquisition. · Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic): Protects individuals from deprivation of property except as allowed by law.

|

Week two: Owner ship based on possession (Topic 2)

Topic 2

2.1 Possession and possessory title

2.2 Native title

2.3 Doctrine of tenure

2.4 Finder’s rights over personal property

In week two we consider possession as the basis for ownership and title to property in Australia. This includes definitions for ‘possession’ ‘seisen’, ‘ownership and title, and the concept of ‘possessory title’. Native Title is a key concept that creates a framework within these concepts are understood in Australia. This includes the common law concept of Native Title as stated by the High Court of Australia, and as recognised by the statutory Native Title legislation.

Terms:

Possession: To physical occupation PLUS control of the land or goods

Seisen: The right to recover possession (of land)

Ownership: the ability to exercise rights over land or goods, according to the interest owned-may or may not include possession

Title: Recognition of ownership by the state

2.1: The concept of possession and possessory title

Overview of possession | Possession is the act of holding or controlling property and is the cornerstone of property rights. It establishes a legal claim to property or land, enabling individuals to exercise rights over their possessions and protecting them from unauthorized dispossession. |

Ways to acquire possession

Acquisition of property though taking possession/possessory title | Possession can be attained through several methods Both the doctrine of tenure and Native title rely on the notions of possession to evidence title (or ownership) to property

- Consent: Gaining permission from the prior owner - Purchase: Obtaining property through a legitimate sale transaction, conferring ownership rights - Gift: Receiving property freely from another party without any exchange of value - Loan: Temporarily holding property with the intention of returning it - Taking possession: Physically controlling an item without the previous owner’s consent, often concerning lost property - Abandonment: An owner may relinquish control, allowing a subsequent possessor to claim rights The limitation period for recovery of property however may defeat an otherwise successful claim to have property restored to the person with better title. See limitation of Act 1958 (Vic) |

What is possession? | Justice Toohey in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) in disucussing the nature of possessory rights said:

“possession” is notoriously difficult to define but for present purposes it may be said to be a conclusion of law defining the nature and status of a particular relationship of control by a person over land ‘Title’ is in the present case, the abstract bundle of rights associated with that relationship of possession. Significantly, it is also used to describe the group of rights which result from possession, but which survives its loss; this included the right to possession” “So long as it is enjoyed, possession gives rise to rights, including the right to defend possession or sell or to devise the interest:”

When asked what possession means what you must point out in that its two elements - Occupation (physical possession) - AND Control |

What is possession? Possession or seisen of real property | In the context of real property “seisen” is an older term, distinct from mere possession, referring to the right to legal possession of a freehold estate in land, while possession is the actual physical control of the property |

Legal status of possession | The right of possession is enforceable against everyone unless a superior title is claimed. This fundamental principle states that mere possession affords certain legal protections. Under the limitation of Actions Act 1958 (Vic), specific timeframes – seven years for land and six years for personal property – are stipulated for initiating recovery actions, highlighting the necessity for prompt legal action in disputes. |

Definition of possession: | Justice Toohey, in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) 1992, defines possession as a legal conclusion denoting control over land or property. It involves both title (which represents the rights associated) and practical possession (the actual control and the intent to maintain that control) |

What is possession? Possession or seisen of real property | · Historically there were sound reasons to protect possession rather than title · How does possession differ from seisen? Seisen: the right to bring action to recover land, or to eject someone from land · No absolute ownership so common law protected persons ‘seised’ of land (in possession of freehold) · Possessor of land gained a right in land enforceable against the world at large except against someone with a superior right · A possessor of land (even wrongfully) may have rights against the world at large but her title may be susceptible to attack from specific people with better title. |

Historical context of possession | Historically, legal frameworks prioritized possession over title, recognizing the need for protections for individuals lacking complete ownership, such as tenants. Even when someone is in possession, they might possess enforceable rights against those who do not have a superior claim

Key historical events - 1640: The case of R v Rudd underscored possession principles - 1824: Introduction to The Statute of Limitations, impacting claims of possession |

Case study Perry v Clissold [1907] AC 73

Rule: Moving on and using land counts as adverse possession.

At 79: ‘It cannot be disputed that a person in possession of land in the assumed character of owner and exercising peaceably the ordinary rights of ownership has a perfectly good title against all the world but that rightful owner’ | What is possession, Possession of real property: Perry v Clissold

- Government gave notice to resume land that was occupied by Clissold (a squatter). Compensation was payable to displaced persons. Before compensation was claimed, Clissold died. His executors took action to recover compensation - Government refused to pay on the basis that Clissold was a trespasser and at that time, had merely a possessory title to the land (not the true owner). - On appeal to the privy council Held that a person in possession of land has perfectly good title against the whole world except the rightful owner. Government could not deny compensation to Clissold if the rightful owner does not come forward.

This landmark ruling by the Privy council upheld Clissold’s claim to occupancy when it was contested by the government, which argued he was a trespasser. The decision confirmed that a person in possession, like Clissold, holds valid title against all but the rightful owner, thereby affirming his claims for compensation. |

2.2 Native title

Historical Recognition of Native Title | The evolution of native title recognition in Australia is marked by significant legal milestones: Chronology - 1971: Australia declared “terra nullius” Millirpum v Nabalco - 1982: Enactment of Queensland (Aboriginal and Islander Land Grants) Act 1982 - 1982: Test case in High Court by Murray Islanders to determine legal rights of islanders to the islands of Mer, Dauar and Waier in Torres Straight (Meriam people in occupation for generations prior to European contract) - 1985: Enactment of Queensland Coast Island Declaration Act 1985 - 1988: Mabo v Queensland (no.1) - 1992: Mabo v Queensland (no.2) Native title officially recognised in Australia |

Nature of native title: | Native title: Australia as “terra nullius” Millirpum v Nabalco [1971] 17 FLR 141 - Claim made by Aboriginal clans located at Yirrkala on the Grove Peninsular of NT, seeking to restrain the mining of bauxite on their traditional lands and challenge the validity of the mining leases granted over these lands by the commonwealth government to Nabalco Pty Ltd. - The plaintiff’s case was dismissed due to the absence of excludability (right to exclude was not apparent and in fact denied) and alienation (expressly repudiated by plaintiffs) characteristics. - Justice Blackburn historically declared that Australia was terra nullius at the time of sovereign acquisition by England, and rejected the ‘native title’ rights of Australia’s Aboriginal people

Native title is rooted in the traditional laws and customs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, signifying their inherent connections to land and water. It remains valid unless explicitly extinguished by legislative measures or other actions, and its applications is evaluated individually based on the community’s connection to the land and recognition by common law. |

Sovereignty and Extinguishment | Sovereign power: The crowns acquisition of sovereignty adds complexity to native title, as indigenous rights can be extinguished when sovereign actions infringe upon them. Legislative measures aiming to extinguish native title must respect existing rights and adhere to the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, a principle upheld in various court rulings, including Mabo v Queensland (No 1) (1988)

- Sovereign capacity to create and extinguish rights and interest in land - Pre-existing rights and interests of native title became vulnerable to extinguishment on acquisition of sovereignty by the valid exercise of sovereign power inconsistent with the continued right to enjoy the native title, e.g. grant of inconsistent estate or interest in land Limitations on the sovereign power to extinguish - Not every act that might extinguish native title can validly be done in disregard of native title rights - Mabo v Queensland (no 1) (1988) 166 CLR 186; Provisions of the racial discrimination act 1975 (cth) operated to restrict the capacity of stake/territory laws to extinguish or reduce native title (inconsistent legislation – Constitution art 109) - Mabo v Queensland (no 2): acquisition of property on ‘just terms’ to restrict commonwealth’s power validly to appropriate/extinguish native title. |

Native title legislation | Native Title Act 1993: The Native Title Act 1993 (NTA) is the foundational legislation that acknowledges and safeguards native title in Australia. it provides a comprehensive framework for identifying native title rights and includes procedural mechanisms for their protection. The act was enacted on January 1, 1994 and has undergone key amendments in 1998 and 2007 to improve its functionality in recognizing and processing native title claims.

Section 3: Objectives - Provides for the recognition and protection of native title - Establishes a mechanism for determining claims to native title

|

Common law recognition of native title: | Mabo v Queensland (No 2) Arguments

Plaintiffs Sought declarations that the Meriam people were entitled to the Murray Islands as owners, as possessors, as occupiers, or as persons entitled to the use and enjoyment of the island

Defendant argued that when the territory of a settled colony became part of the Crown’s dominions, the law of England became the law of the colony and, by that, the Crown acquired absolute beneficial ownership of all the land in the territory so that the land could thereafter be possessed by other person unless granted by the crown.

Held (Generally) · Upon settlement the crown acquired sovereignty over the territory and radical title – this is not justiciable · Australia was not terra nullius – radical title upon settlement did not confer on the Crown absolute beneficial ownership of land occupied by Indigenous inhabitants · Common law of Australia recognises a form of native title where not extinguished · Extinguishment does not give rise to compensation (not held by entire majority see Deane, Toohey and Guadron who state otherwise) · Native title exists where clear indication to the fact from pre-1788

|

Native title Act 1993 (Cth): Statutory definition of native title | Native title not a create of common law or statute (Yorta Yorta case) · NTA section 223: Native title; native title rights and interest means communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples to land or water. - (a) possessed under traditional laws/ traditional customs and - (b) by those laws and customs enable a connection between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the land/water and; - (c) are rights/interests recognised by common law of Australia

· ‘Traditional’ used in a special sense to convey ‘an understanding of the agent of the traditions’ – to normative rules in societies that existed before the assertion of sovereignty · ‘Rights and interests recognised by common law’: Enables rights/interests antihertical to fundamental tenants of common law to be refused. Emphasizes the intersection between legal systems and the time of sovereignty · ‘Connection between Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people and land/water’: Must be able to be translated into ‘rights and interests’ |

Native title Act 1993 (Cth) | · The scope of native title has changed over time: Wik peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1, held that native title could co -exist over land with pastoral leases · Native title claims are complex and resource intensive: Burden on claimants compares to benefits received. · Reviews and reform of NTA processes - 2015: Australian law reform commission: Connection to Country: A review of the Native Title Act 1993 |

2.3 Doctrine of tenure

Understanding the Doctrine: The doctrine of Tenure posits that ultimate ownership of all land in Australia resides with the Crown, with individual interests granted through Crown leases or titles. This historic doctrine limits the concept of absolute ownership, focusing on hierarchical relationships that are reminiscent of feudal systems, where the right to land are conferred rather than owned outright.

Impact on Australian Land Law: Australia’s adaptation of this doctrine has enabled the structing of land claims based on the sovereignty demonstrated during colonization in 1788. The Mabo ruling denoted a pivotal shift, acknowledging that native title exists outside the traditional tenurial framework, disrupting prevailing assumptions of crown land ownership.

- The doctrine of tenure has historical application in the English legal system

- The doctrine stands for the position that the Crown (historically the kind) owns all land and that any interest in land is conferred by a Crown grant. This position means that one person never has “absolute” ownership of land. Proprietary rights are ultimately subject to the Crown’s ‘ownership’,

1.3 Australia’s modified doctrine of tenure

· While Australia never had a feudal system, the Doctrine of Tenure was applied here on the basis that Australia was terra nullius (Mirrilpum v Nabalaco)

· From colonisation in 1788 the British Crown claimed absolute sovereignty over Australia, conferring on itself the power to control the territory and make laws with respect to it. This included the right to issue grants over any part of the land and to assert absolute beneficial ownership over unalienated lands

· Since the Mabo decision in 1992, the Doctrine of Tenure that applies in Australia has formally been ‘modified’ by the recognition of native title rights that exist outside the tenurial system, neither granted by the Crown, not existing as an estate held from the crown. Justice Brennan reasoned:

‘The doctrine of tenure applies to every Crown grant of an interest in land, but not to rights and interests which do not own their existence to a crown grant...it is only the fallacy of equating sovereignty and beneficial ownership of land that gives rise to the notion that native title is extinguished by the acquisition of sovereignty’

2.4 Finders rights over personal property

General principles

The ‘finder’s keepers’ principle indicated that finders acquire rights through lawful possession, which are enforceable against all parties except the original owner. the principle is intrinsic to common law, providing clarity regarding rights related to lost property.

Armory v Delamirie (1722) 1 Strange 505

· General principle: Finder’s rights are based on their lawful possession and control of found items, which are good against the whole world except someone claiming a prior right based on possession/control, or the rights of the true owner:

Key cases

Armory v Delamirie (1722) The ‘Finders keepers rule’ | This case if foundational for ‘finders rights’ establishing that possession, even without title, bestows rights against all but the true owner.

General principle: Finder’s right are based on their lawful possession and control of found items; which are good against the whole world except someone claiming a prior right based on possession/control, or the rights of the true owner “That the finder of a jewel, though he does not by such finding acquire an absolute property or ownership, yet he has such a property as will enable him to keep it against all but the rightful owner, and consequently may maintain trover” |

Parker v British Airways board (1982) | This case reinforced that finders who take reasonable steps to locate the true owner of lost property maintain their rights, balancing the interest of finders and property owners.

Facts: - Parker found a man’s gold bracelet inside a British airways lounge at Heathrow. While BAP might have some rights over the bracelet as the occupier of the premises where it was located, it is also true that a finder, without prospect of reward, would be tempted to conceal the bracelet without taking action to locate its true owner.

Rights and obligations of finders [1017] A finder acquires rights - To an item that has been abandoned/lost IF the item is lawfully taken into their care and control; - If they act honestly and take reasonable steps to find the owner. - In the course of employment ONLY if agreed with their employer.

Obligations and liabilities of occupiers [1017-8]: An occupier has superior rights (over a finder) for items attached to occupied land OR if the occupier manifests an intention to exercise control over the building and the items which may be in or on it IF the occupier takes reasonable measures to ensure lost items are found and returned to their true owner.

Held: Parker’s possession was lawful. P acted honestly and reasonably in handing in bracelet to BAP. BAP did not have sufficient control of premise to acquire rights superior to P.

|

Obligations of funders and Occupiers | Finders have a responsibility to act in good faith, attempting to return lost items to their rightful owners, while occupiers of property retain superior rights regarding items found within their premises, outlining a structured hierarchy in possession rights |

Concept of Abandonment | Definition and legal implications: Abandonment occurs when an owner intentionally relinquishes their property rights. This may lead to legal claims for detinue (wrongful retention of someone else’s goods) or conversion (Unauthorized dealing with another’s property) if others subsequently take or retail the abandoned property. The legal implications of abandonment are critical in resolving competing claims regarding possession. |

Note: Abandonment of goods | · In a property law sense, the term abandonment is essentially linked with some sort of property right in a chattel and not in real property. Real property (other than things such as incorporeal hereditament e.g., easements) cannot be abandoned. Leases may be abandoned (Chattels real) · The law on abandonment is not settled. Case law suggests that two things must occur for property to be abandoned 1. An act by the owner that clearly shows that he or she has given up rights to the property and not merely an intention to relinquish possession. 2. An intention that demonstrates that the owner has knowingly relinquished control over the property · A claim of detinue, trespass to goods or conversion may arise when another person wrongfully takes or retains property |

Week three: Adverse Possession

In Week 3 we consider how rights in real property may be acquired through possession under the Doctrine of Adverse Possession. Alternative means of resolving disputes involving boundary encroachments are also discussed

3.1 Adverse possession

Adverse possession is where someone has possession of land without permission of the person with the right to immediate possession. Under the Australian Limitation statutes, the person with the right to immediate possession will lose their right to recover land from the person in adverse possession after a prescribed period. This limitation is supported on numerous policy grounds. In Victoria the relevant statute is the Limitation of Actions Act 1958 (Vic) (LAA)

Defining adverse possession

There is no statutory definition of adverse possession. However, a legal description of adverse possession and the prerequisite elements to its establishment can be found in common law.

Defining 'adverse possession' | Common law concept of 'adverse possession'

Adverse possession is a doctrine recognised in common law jurisdictions, allowing a person to claim ownership of land under specific conditions even if they do not hold the title. It typically occurs when someone occupies land without their permission of the true owner for a legally specified period. |

Legal right to recover | Despite the possibility of gaining ownership through adverse possession, the original owner retains the right to recover their land through legal means. However, this right is subject to the time limitations imposed by the Limitation of Actions Act 1958 (Vic), which dictates that the original owner must act within a designated time frame to make a claim against the possessor. |

What is "adverse possession"? | A person claiming title to land by adverse possession must prove:

Both are determined objectively, as questions of fact: By looking at the nature of land and the manner in which it is commonly used and enjoyed. |

What is adverse possession: Factual possession |

|

Factual possession continued |

|

Adverse Possession: Intention to possess |

|

3.1 Factual Possession case law

The first thing to do when trying to work out an adverse possession claim is to establish what constitutes adverse possession at common law.

What is factual possession? | Factual possession, In the context of property law, refers to the physical control and exclusive use if land, demonstrating an appropriate degree of control over the land, open to public view and without the consent of the true owner. - Looks at the character of the land itself. In the case of JA Pye v Graham were looking at land enclosed by hedges and having an entry to a lock gate. This is physical possession and control over land given it is farmland. - Hedges and a lock gate constitute factual possession |

Case Law (JA Pye oxford v Graham [2003] 1 AC419

Factual Possession | Facts:

Factual possession?

|

Whittlesea City Council v Abbatangelo [2009] VSCA 188

Factual Possession | Facts:

Factual possession?

|

Buckinghamshire Council v Moran [1990] Ch 623

“When the law speaks of an intention to exclude the world at large, including the true owner, it does not mean that there must be a conscious intention to exclude the true owner. | Facts

Factual possession

|

Adverse possession intention to possess: Case law

|

Mention is a continuous intention to possess that is not negated by knowing that the true owner has other uses of the land or knowing that their possession may eventually end. |

3.2 Statutory requirements to establish ‘adverse possession’

The Australian limitation statutes with respect to actions to recover land vary. Under the Victorian LAA, statutory provisions establish time limits for the recovery of land, land capable of being adversely possessed, as well as circumstances that "start" or "stop" time from running. Special provisions address land subject to leasehold estates, and future estates or interests in land.

Successive adverse possessors

Over the duration of the statutory limitation period, both the documentary title owner, and the person in adverse possession of land, may change. A change in the documentary title ownership of the land in dispute does nothing to affect the running of the limitation period. However, changes to the person in adverse possession must meet certain criteria to be aggregated together. If not, then the statutory limitation period starts again.

Adverse possession and Torren’s system land

Registered interests in Torren’s system land enjoy protection against interference from persons claiming competing, unregistered, interests in the same land (topic 4). However, statutory exceptions to this position include the rights of an adverse possessor - therefore change to the documentary title ownership of land does not affect the running of the limitation period. The TLA also provides a process by which a person having satisfied the statutory limitation period and Doctrine of Adverse Possession to become an 'owner' of land at common law, can become the documentary title owner of land and registered as such in the land register.

3.2 Statutory requirements 'Booked provisions' LAA s 8, 18 | Key framework

Note: Period of limitation in contract or tort is 6 years LAA s 5 |

Statutory requirements Time starts to run.

LAA s 9(1), 14(1) | In property law, time starts running on limitation periods from when the cause of action accrues, which is when all the necessary elements for a claim come into existence. The specific accrual point can vary depending on the type of claim. Time stops running once a limitation period has been suspended, usually through a standstill agreement or a court order, or when the claim is settled or resolved.

When does time begin to run?

Plus

|

3.2 Statutory requirements who can be adversely possessed? | Land owned by specific entitles entities cannot be adversely possessed The law specifically exempts certain types of land from being subject to adverse possession or claims. These mainly include land owned by government and other public entitles. The law provides a shield against adverse possession for these types of land, ensuring that public land remains under the control of the appropriate authorities.

|

3.2 Statutory requirements periods of possession | Periods of possession

In Victoria the time limit for a successful adverse possession claims in 15 years continuous, uninterrupted and exclusive possession of the land. This means the claimant must have been in actual possession of the land for at least 15 years, and this possession must not have been with the permission of the legal owner.

- This can occur even if possession is transferred informally between APs - If an AP abandons land without the 15-year period being satisfied, then the time must be re satisfied in full. If the time is satisfied, the right can be accrued once the AP re-enters possession. |

3.2 Periods of possession: Mulcahy v Curramore |

|

3.2 Statutory requirements: When does time stop running | When does time stop "running"?

Time stops running in property law primarily through the successful completion of adverse possession, the expiry of the applicable limitation period, or through specific events that interrupt or restart the time running such as standstill agreements or hardship situations. Assertion of superior title

|

3.2 Case examples: Outcome | Was adverse possession proven in our cases? Was title of the owner extinguished? Was process did the adverse possessor take to assert their rights

|

Explaining: Special rules of adverse possession

Future interests in land

Land subject to leases (Tenancy)

3.2 Adverse possession: Other issues Future interests in land | Special rules to determine WHEN time starts to run: LAA s 9(2); 10(1)

LAA s 9(2): Accrual of right of action in case of present interests in land

LAA s 10(1): Accrual of right of action in cases of future interests

|

3.2 Adverse possession: Other issues future interests in land | Special rules determine LENGTH of statutory time period: LAA s 10(2)

LAA s10(2): Accrual of rights of action in case of future interests

This section is about limitation period for bringing an action (like recovering possession of land) when someone has a future interest – e.g., a remainder or reversion – that comes into effect after someone else’s estate ends 1. There’s a preceding interest (e.g., life estate) and a succeeding interest (e.g., a remainder after that life estate) 2. When the preceding estate ends, you look what whether that person was in possession of the land, if they were in possession, this rule applies. 3. Then, the person with the succeeding interest has a time limit to bring a legal action - They have 15 years from when the right of action arose for the preceding interest-holder or - 6 years from when the right arose for those succeeding interest-holder themselves - Whichever of these two-time limits ends last. |

3.2 Adverse possession: Other issues Tenancy arrangements |

|

Transfer of Land provisions

Adverse possession to registered proprietor

3.2 Adverse possession: Adverse possession of Torrens System land | Pursuant to the transfer of land act ss 60-62, the AP can become the registered owner of the interest in question

|

3.3 Encroachment of boundaries (This is the element of the smallest type of trespass)

Encroachments | Where possession is in dispute between adjacent owners, or around boundaries: fences, overhanging eaves, driveways, etc, may be dealt with differently to traditional rules of adverse possession. In Victoria, legislation does not prevent adverse possession of a part of land,

|

Encroachments Break Fast investments v PCH Melbourne [2007] VSCA 311 | Break Fast and PCH owned adjoining property in East Melbourne. Break fast had refurbished an office block on its property, building along the common boundary. Mental cladding on building encroached onto PCH's land by 6cm. PCH sought an injunction against Break Fast for trespass.

Primary judge: Encroachment was "not trifling" and exceeded tolerance of 'a little less a little more' under PLA. Encroachment prevented PCH from building upon the boundary of its own land. Cost of removal would exceed $300, 000.

Court of appeal: While PCH prima facie entitled to an injunction to prevent encroachment, damages may be awkward in lieu of remedy in exceptional circumstances.

|

3.3 Encroachments

Break Fast investments v PCH Melbourne [2007] VSCA 311

Good working rule:

The relevant test is not whether the incursion actually interferes with the occupier’s actual use of the land at the time but rather whether it is of such a nature and at a height which may interfere with the ordinary uses of the land which the occupier may see fit to undertake.

Injunction to prevent encroachment may be ordered upon satisfaction of the good working rule

Injury is small AND

Injury capable to be estimated in monetary terms AND that amount is small AND

It would be oppressive to grant an injunction

In this case: injury to PCH was not small; injury was capable of being estimated in monetary terms, but the amount was not small; it was not oppressive to grant an injunction.

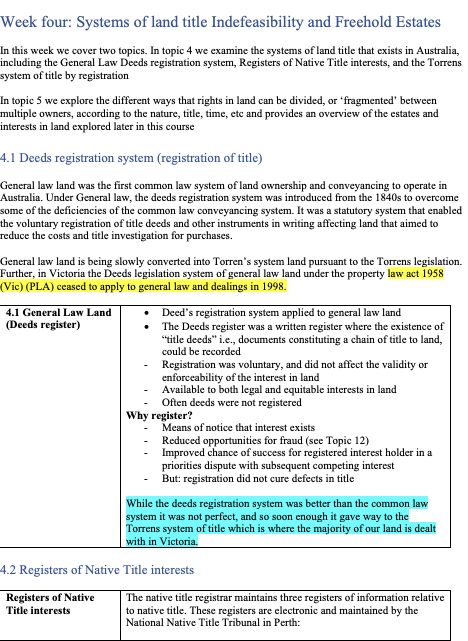

Week four: Systems of land title Indefeasibility and Freehold Estates

In this week we cover two topics. In topic 4 we examine the systems of land title that exists in Australia, including the General Law Deeds registration system, Registers of Native Title interests, and the Torrens system of title by registration

In topic 5 we explore the different ways that rights in land can be divided, or ‘fragmented’ between multiple owners, according to the nature, title, time, etc and provides an overview of the estates and interests in land explored later in this course

4.1 Deeds registration system (registration of title)

General law land was the first common law system of land ownership and conveyancing to operate in Australia. Under General law, the deeds registration system was introduced from the 1840s to overcome some of the deficiencies of the common law conveyancing system. It was a statutory system that enabled the voluntary registration of title deeds and other instruments in writing affecting land that aimed to reduce the costs and title investigation for purchases.

General law land is being slowly converted into Torren’s system land pursuant to the Torrens legislation. Further, in Victoria the Deeds legislation system of general law land under the property law act 1958 (Vic) (PLA) ceased to apply to general law and dealings in 1998.

4.1 General Law Land (Deeds register) | · Deed’s registration system applied to general law land · The Deeds register was a written register where the existence of “title deeds” i.e., documents constituting a chain of title to land, could be recorded - Registration was voluntary, and did not affect the validity or enforceability of the interest in land - Available to both legal and equitable interests in land - Often deeds were not registered Why register? - Means of notice that interest exists - Reduced opportunities for fraud (see Topic 12) - Improved chance of success for registered interest holder in a priorities dispute with subsequent competing interest - But: registration did not cure defects in title

While the deeds registration system was better than the common law system it was not perfect, and so soon enough it gave way to the Torrens system of title which is where the majority of our land is dealt with in Victoria. |

4.2 Registers of Native Title interests

Registers of Native Title interests | The native title registrar maintains three registers of information relative to native title. These registers are electronic and maintained by the National Native Title Tribunal in Perth:

· Register of Native Title claims: Contains information about native title claimant applications that have satisfied the conditions for registration (registration test): Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) s 190A · National Native Title register: Contains information of all approved determinations of native title in Australia · Register of Indigenous land use agreements contains information about Indigenous land use agreement made between people who hold/may hold native title in the area and other people, organisations, or governments

The information in these registers is particularly important for parties involved in native title claims applications, especially the spatial dataset information which represents the external boundaries of all native title claimant applications, approved determinations, land use agreements and further act notices. |

Registers of Native Title interests | · Native title register is maintained by a registrar · Registrar is required to keep register up to date in relation to claims to native title, native title interests and land use agreements · Registrar may decide In the public interest, that parts of the register should be kept confidential · Registrar is responsible for informing land titles officials about native title determinations etc. |

4.3 Torrens system (title by registration)

The Torrens system is the dominant system of land title in Australia. This system of title by registration was enacted to address the “losses, heavy costs, and much perplexity that arose because the existing law was complex, cumbrous, and unsuited” to the requirements of local inhabitants’ (Real Property Act 1858 (SA), preamble). The Torrens System replaces the General Law Land System (Deeds) as the registration system applicable to over 99% of land in Victoria. The three objects of Torrens are (i) mirror, (ii) curtain, and (iii) insurance.

In the Torrens System, title to land is acquired by registration of estates and interests in land on a central Register. A Register is kept in each Australian State and Territory under Torrens legislation by Registrar. In Victoria, the ‘Torren statute’ is the Transfer of Land Act 1958 (Vic) (TLA). Within the Register, records of land and interests in land are recorded by unique ‘Volume’ and ‘Folio’ numbers. Documents that evidence the estates and interests are recorded against the land by Volume and Folio, as identified as ‘instruments.’ See Topic 10.

Terminology

Instrument | means a document that is lodged with the Registrar in order to register a specific estate or interest in land on the central Register. Each instrument has a unique number (‘dealing number’ / ‘instrument number’) |

Register | Central register of interests maintained by Registrar under TLA s 27 |

Registrar | Registrar of Titles, administrator of the Register. |

Registered interest | An interest that may be registered under the Torrens System is known as a “registrable” interest, or an interest that is “capable of registration”. The interest can become ‘registered’ by producing documents that meet the requirements of the Torrens Statute – ie are in “registrable form” – and lodging these for registration with the Registrar. |

Volume and folio | applies to proprietary interests that are (a) not capable of registration, or (b) are capable of registration but are not registered. While all ‘registered interests’ are legal, not all legal interests are registrable/registered – it is important to distinguish between the nature and registered status of instruments even though these terms are often used interchangeably. |

“unregistered interest” | Volume and Folio identifier/numbers are the unique numbers assigned to all parcels of land. |

Indefeasibility | Indefeasibility means that the title of the registered proprietor is subject only to such estates and interests as are recorded on the title. |

4.3 The Torrens system

The Torrens system | The Torrens title system is a land title registration system where ownership and interests in land are recorded in a central register, guaranteeing title and providing security for property transactions

The Torrens system works on three principles: The land titles register accurately and completely reflects the current ownership and interests of a parcel of land, because the register contains this information, it means ownership and other interests do not have to be provided by title deeds. |

Torren’s system objectives | · The Torrens system was first introduced as the Real Property Act (SA) · The Torrens system was introduced in Australia to resolve the ‘losses’ heavy costs and much perplexity that arose because the existing law was complex, cumbrous, and unsuited to the requirements of local inhabitants (RPA 1858 Preamble) · Or in other words, provide a system of land title by registration based on the underlying principles of - Mirror: Accurate and complete reflection of the current ownership and interests in a person’s land - Curtain: Proof of title; no need to investigate chain of title - Insurance: Statute guarantees the register with compensation system (loss-based register error) |

Key principles | Title by registration: Ownership of land is determined by registration in the Torrens title register, not by the possession of title deeds

Indefeasibility of title: Once a title is registered, it is considered valid and cannot be challenged, even if there are prior claims or defects in the title

Centralized register: The Torrens title system relied on a central register that accurately and completely reflects ownership and interests in land

Guaranteed title: The state government guarantees the title, and a Torrens Assurance Fund (TAF) provides compensation for any loss suffered due to fraud or error in registration. |

The Torrens system vs title deeds | The recording of the deed served to give notice to the world of the conveyance of title to the grantee named in the deed. The basic difference between the deeds registration and Torren’s systems is that the former involves registration of instruments while the latter involves registration of title.

The Torrens system, a method for registering land ownership, differs from title deeds in that it provides a simplified, secure, and transparent framework where ownership is determined by the register, not by tracing historical deeds. |

Torren’s system Converting land to ‘Torren’s land’ | Since 1862, general law land has been converted to ‘Torren’s system’ land at varying rates. - Less than 1% of all land in Victoria remains outside the Torrens system (churches, mechanics institutes) - TLA s 8: Unalienated Crown land is deemed to be under the Torrens system - TLA s 9: The registrar may convert general law land to Torren’s land (usually at the time of dealing)

|

The Torrens system objectives

| - The Torrens system was first introduced as the Real property Act 1858 (SA) - The Torrens system was introduced in Australia to resolve the “losses and heavy costs, and much perplexity that arose because the existing law was complex, cumbrous and unsuited” to the requirements of local inhabitants (RPA 1858 Preamble). - Or in other words, provide a system of land title by registration based on the underlying principles of:

Mirror: Accurate and complete reflection of the current ownership and interests in a person’s land

Curtain: Proof of title; no need to investigate chain of title

Insurance: State guarantees the register with compensation system (loss based on register error) |

Torren’s system key feature: Central register | The central feature of the Torrens system is its register, what we mean by title by registration is that you gain your title to land by registration and that’s what distinguishes it from deeds which was a system of registration of title

Torren’s system established a system of title by registration (cf registration of title). In Victoria the Torrens statutes is the Transfer of Land Act 1958 (Vic)

Key features · The registrar administers the central register of registered interests in land (TLA s 27) · The certificate of title is the register entry for each parcel of land, showing fragmented interests in that land · Certificates of title are identified by a unique reference number: Volume and Folio numbers |

Torren’s system converting land to ‘Torren’s land’ | Since 1862, general law land has been converted to ‘Torren’s system’ land at varying rates. - Less than 1% of all land in Victoria remains outside the Torrens system (churches, mechanics institutes etc)

TLA s 8: Unalienated crown land is deemed to be under the Torrens system

TLA s 9: The registrar may convert general law land to Torren’s land (usually at the time of dealing) |

Torren’s system registration of interests (mirror objective) | The key principle of the Torrens system, which together establish indefeasibility of title, are: Mirror principle – The land titles register accurately and completely reflects the current ownership and interest about a person’s land

Registered interest: Interest identified on the certificate of title within the register. Registration confers protection by indefeasibility.

Compare with: - “Registrable interest” - “registrable form” - Interests or information “recorded” or “noted” - “unregistered” “unregistrable”

|

Process of registration registered vs unregistered interests | However, the Torrens system also recognises that some interests in land many are not registered (or even capable of registration). The Torrens system even though it wants to be a mirror and curtain there are interests that are not able to record in the Torrens system but nonetheless they exists outside Torrens and they are legitimate interests In land

Barry v Helder (1914) 19 CLR 197 “The Torrens statutes do not touch the form of contracts. A proprietor may contract as he pleases, and his obligation to fulfil the contract will depend on ordinary principles and rules of law and equity...in denying effect to an instrument until registration, does not touch whatever rights are behind it. Parties may have a right to have such an instrument executed and registered and that right, according to accepted rules of equity is an estate or interest in land”

Abigail v Lapin [1934] AC 491 at 500 “The statutory form of transfer…when registered... is effective to pass the legal title.” |

Torren’s system: Principle of Indefeasibility (Curtain objective)