Covalent Bonding lewis structures

We begin our discussion of the relationship between structure and bonding in covalent compounds by describing the interaction between two identical neutral

atoms

—for example, the H2molecule, which contains a purely

covalent bond

. Each hydrogen atom in H2contains one electron and one proton, with the electron attracted to the proton by electrostatic forces. As the two hydrogen

atoms

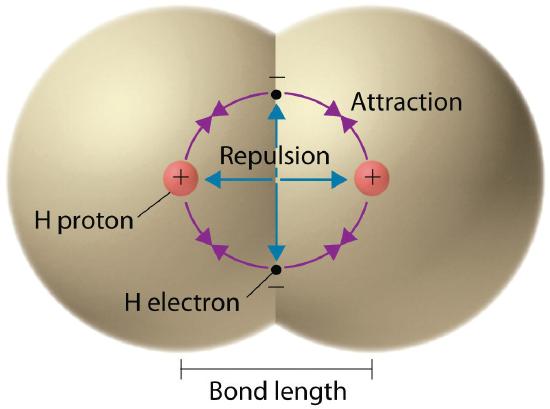

are brought together, additional interactions must be considered (Figure9.5.19.5.1):

The electrons in the two

atoms

repel each other because they have the same charge (

The electrons in the two

atoms

repel each other because they have the same charge (E > 0).

Similarly, the protons in adjacent

atoms

repel each other (E > 0).

The electron in one atom is attracted to the oppositely charged proton in the other atom and vice versa (E < 0). Recall that it is impossible to specify precisely the position of the electron in either hydrogen atom. Hence the

quantum

mechanical probability distributions must be used.

Figure 9.5.19.5.1: Attractive and Repulsive Interactions between Electrons and Nuclei in the Hydrogen Molecule. Electron–electron and proton–proton interactions are repulsive; electron–proton interactions are attractive. At the observed bond distance, the repulsive and attractive interactions are balanced.

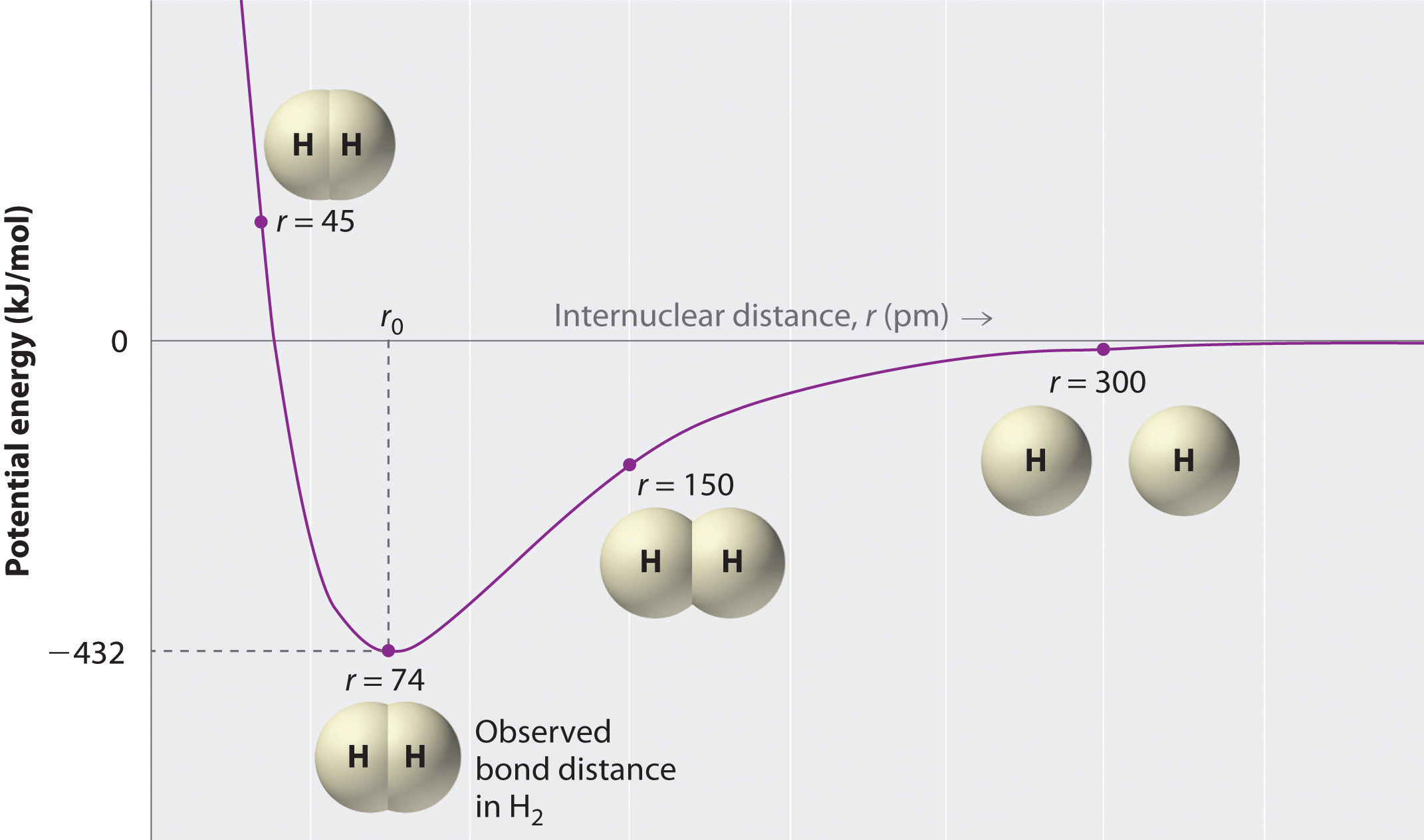

A plot of the potential energy of the system as a function of the internuclear distance (Figure 9.5.29.5.2) shows that the system becomes more stable (the energy of the system decreases) as two hydrogen

atoms

move toward each other from

r

= ∞, until the energy reaches a minimum at

r

=

r

0(the observed internuclear distance in H2is 74 pm). Thus at

intermediate

distances, proton–electron attractive interactions dominate, but as the distance becomes very short, electron–electron and proton–proton repulsive interactions cause the energy of the system to increase rapidly. Notice the similarity between Figures9.5.19.5.1and9.5.29.5.2, which described a system containing two oppositely charged

ions

. The shapes of the energy versus distance curves in the two figures are similar because they both result from attractive and repulsive forces between charged entities.

Figure 9.5.29.5.2: A Plot of Potential Energy versus Internuclear Distance for the Interaction between Two Gaseous Hydrogen

Atoms

.

At long distances, both attractive and repulsive interactions are small. As the distance between the

atoms

decreases, the attractive electron–proton interactions dominate, and the energy of the system decreases. At the observed bond distance, the repulsive electron–electron and proton–proton interactions just balance the attractive interactions, preventing a further decrease in the internuclear distance. At very short internuclear distances, the repulsive interactions dominate, making the system less stable than the isolated

atoms

.

Using Lewis Dot Symbols to Describe Covalent Bonding

The valence electron configurations of the constituent

atoms

of a covalent compound are important factors in determining its structure, stoichiometry, and properties. For example, chlorine, with seven

valence electrons

, is one electron short of an octet. If two chlorine

atoms

share their unpaired electrons by making a

covalent bond

and forming Cl2, they can each complete their valence shell:

Each chlorine atom now has an octet. The electron pair being shared by the

atoms

is called a bonding pair; the other three pairs of electrons on each chlorine atom are called lone pairs. Lone pairs are not involved in covalent bonding. If both electrons in a

covalent bond

come from the same atom, the bond is called a

coordinate covalent bond

. Examples of this type of bonding are presented in Section 8.6 when we discuss

atoms

with less than an octet of electrons.

We can illustrate the formation of a water molecule from two hydrogen

atoms

and an oxygen atom using Lewis dot symbols:

The structure on the right is the Lewis electron structure, or Lewis structure, for H2O. With two bonding pairs and two lone pairs, the oxygen atom has now completed its octet. Moreover, by sharing a bonding pair with oxygen, each hydrogen atom now has a full valence shell of two electrons. Chemists usually indicate a bonding pair by a single line, as shown here for our two examples:

The following procedure can be used to construct Lewis electron structures for more complex molecules and

ions

:

Arrange the

atoms

to show specific connections. When there is a central atom, it is usually the least electronegative element in the compound. Chemists usually list this central atom first in the chemical formula (as in CCl4 and CO32−, which both have C as the central atom), which is another clue to the compound’s structure. Hydrogen and the halogens are almost always connected to only one other atom, so they are usually terminal rather than central.

Determine the total number of

valence electrons

in the molecule or ion. Add together the

valence electrons

from each atom. (Recall that the number of

valence electrons

is indicated by the position of the element in the

periodic table

.) If the species is a

polyatomic

ion, remember to add or subtract the number of electrons necessary to give the total charge on the ion. For CO32−, for example, we add two electrons to the total because of the −2 charge.

Place a bonding pair of electrons between each pair of adjacent

atoms

to give a single bond. In H2O, for example, there is a bonding pair of electrons between oxygen and each hydrogen.

Beginning with the terminal

atoms

, add enough electrons to each atom to give each atom an octet (two for hydrogen). These electrons will usually be lone pairs.

If any electrons are left over, place them on the central atom. We will explain later that some

atoms

are able to accommodate more than eight electrons.

If the central atom has fewer electrons than an octet, use lone pairs from terminal

atoms

to form multiple (double or triple) bonds to the central atom to achieve an octet. This will not change the number of electrons on the terminal

atoms

.

Now let’s apply this procedure to some particular compounds, beginning with one we have already discussed.

The central atom is usually the least electronegative element in the molecule or ion; hydrogen and the halogens are usually terminal.

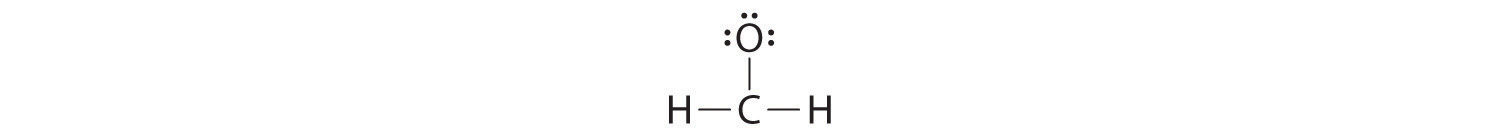

The H2O𝐻2𝑂 Molecule

Because H

atoms

are almost always terminal, the arrangement within the molecule must be HOH.

Each H atom (group 1) has 1 valence electron, and the O atom (group 16) has 6

valence electrons

, for a total of 8

valence electrons

.

Placing one bonding pair of electrons between the O atom and each H atom gives H:O:H, with 4 electrons left over.

Each H atom has a full valence shell of 2 electrons.

Adding the remaining 4 electrons to the oxygen (as two lone pairs) gives the following structure:

This is the Lewis structure we drew earlier. Because it gives oxygen an octet and each hydrogen two electrons, we do not need to use step 6.

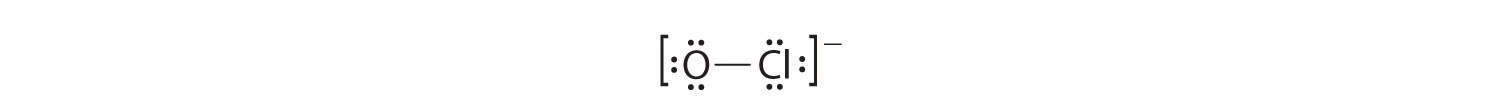

The OCl−𝑂𝐶𝑙− Ion

With only two

atoms

in the molecule, there is no central atom.

Oxygen (group 16) has 6

valence electrons

, and chlorine (group 17) has 7

valence electrons

; we must add one more for the negative charge on the ion, giving a total of 14

valence electrons

.

Placing a bonding pair of electrons between O and Cl gives O:Cl, with 12 electrons left over.

If we place six electrons (as three lone pairs) on each atom, we obtain the following structure:

Both the oxygen and chlorine have 3 electron pairs drawn around them with a bond drawn between them. The molecule has square brackets placed around it and has a negative charge.

Each atom now has an octet of electrons, so steps 5 and 6 are not needed. The Lewis electron structure is drawn within brackets as is customary for an ion, with the overall charge indicated outside the brackets, and the bonding pair of electrons is indicated by a solid line. OCl− is the hypochlorite ion, the active ingredient in chlorine laundry bleach and swimming pool disinfectant.

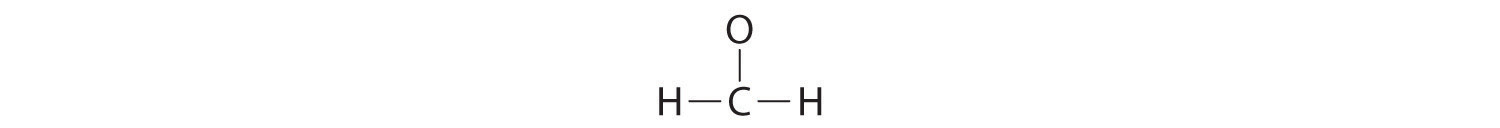

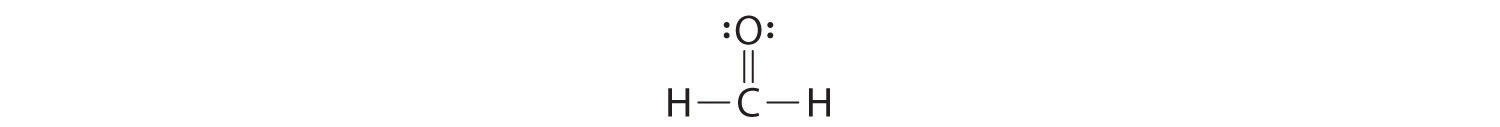

The CH2O𝐶𝐻2𝑂 Molecule

1. Because carbon is less electronegative than oxygen and hydrogen is normally terminal, C must be the central atom. One possible arrangement is as follows:

2. Each hydrogen atom (group 1) has one valence electron, carbon (group 14) has 4

valence electrons

, and oxygen (group 16) has 6

valence electrons

, for a total of [(2)(1) + 4 + 6] = 12

valence electrons

.

3. Placing a bonding pair of electrons between each pair of bonded

atoms

gives the following:

Six electrons are used, and 6 are left over.

4. Adding all 6 remaining electrons to oxygen (as three lone pairs) gives the following:

Although oxygen now has an octet and each hydrogen has 2 electrons, carbon has only 6 electrons.

5. There are no electrons left to place on the central atom.

6. To give carbon an octet of electrons, we use one of the lone pairs of electrons on oxygen to form a carbon–oxygen double bond:

The bond between the oxygen and carbon is replaced with a double bond. The oxygen also has two lone pairs drawn.

Both the oxygen and the carbon now have an octet of electrons, so this is an acceptable Lewis electron structure. The O has two bonding pairs and two lone pairs, and C has four bonding pairs. This is the structure of formaldehyde, which is used in embalming fluid.

An alternative structure can be drawn with one H bonded to O. Formal charges, discussed later in this section, suggest that such a structure is less stable than that shown previously.

Example 9.5.19.5.1

Write the Lewis electron structure for each species.

NCl3

S22−

NOCl

Given: chemical species

Asked for: Lewis electron structures

Strategy:

Use the six-step procedure to write the Lewis electron structure for each species.

Solution:

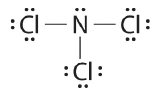

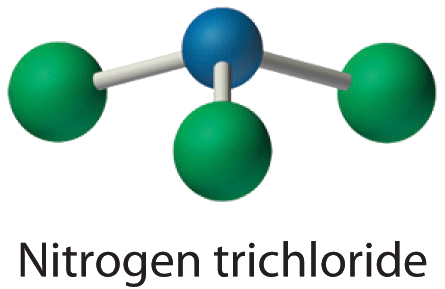

Nitrogen is less electronegative than chlorine, and halogen

atoms

are usually terminal, so nitrogen is the central atom. The nitrogen atom (group 15) has 5

valence electrons

and each chlorine atom (group 17) has 7

valence electrons

, for a total of 26

valence electrons

. Using 2 electrons for each N–Cl bond and adding three lone pairs to each Cl account for (3 × 2) + (3 × 2 × 3) = 24 electrons. Rule 5 leads us to place the remaining 2 electrons on the central N:

Nitrogen trichloride is an unstable oily liquid once used to bleach flour; this use is now prohibited in the United States.

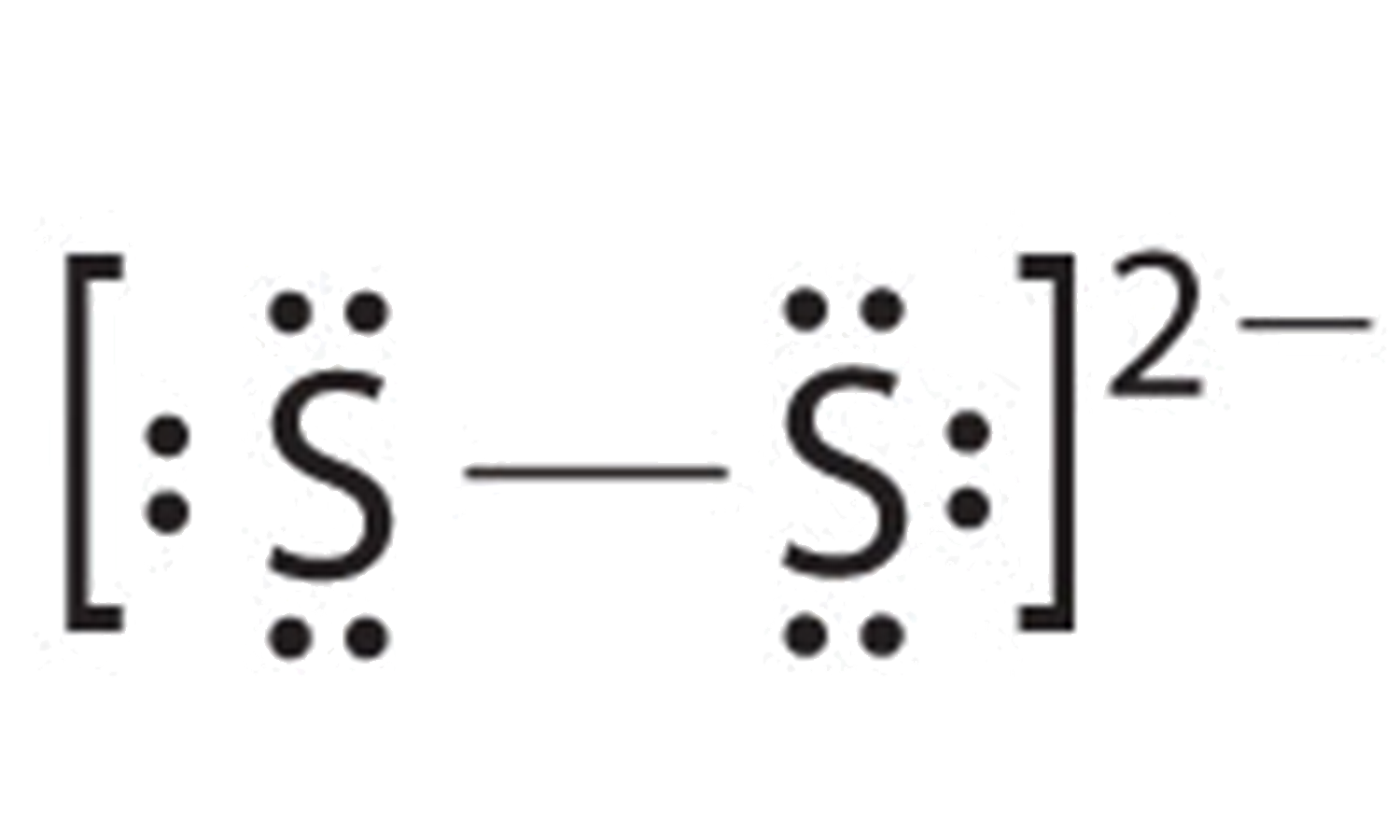

In a diatomic molecule or ion, we do not need to worry about a central atom. Each sulfur atom (group 16) contains 6

valence electrons

, and we need to add 2 electrons for the −2 charge, giving a total of 14

valence electrons

. Using 2 electrons for the S–S bond, we arrange the remaining 12 electrons as three lone pairs on each sulfur, giving each S atom an octet of electrons:

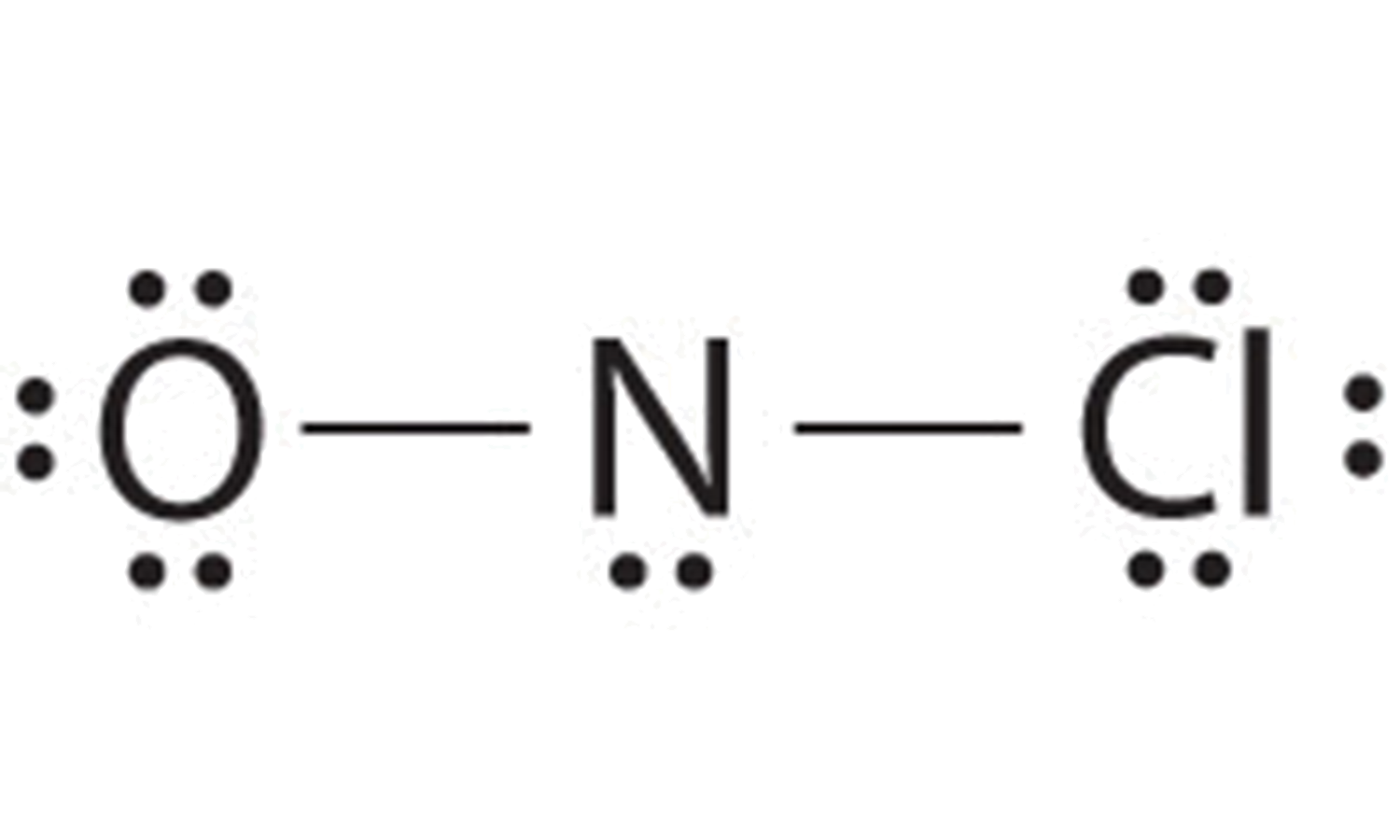

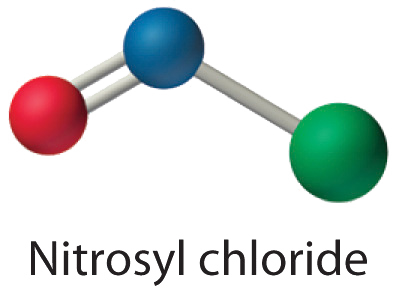

Because nitrogen is less electronegative than oxygen or chlorine, it is the central atom. The N atom (group 15) has 5

valence electrons

, the O atom (group 16) has 6

valence electrons

, and the Cl atom (group 17) has 7

valence electrons

, giving a total of 18

valence electrons

. Placing one bonding pair of electrons between each pair of bonded

atoms

uses 4 electrons and gives the following:

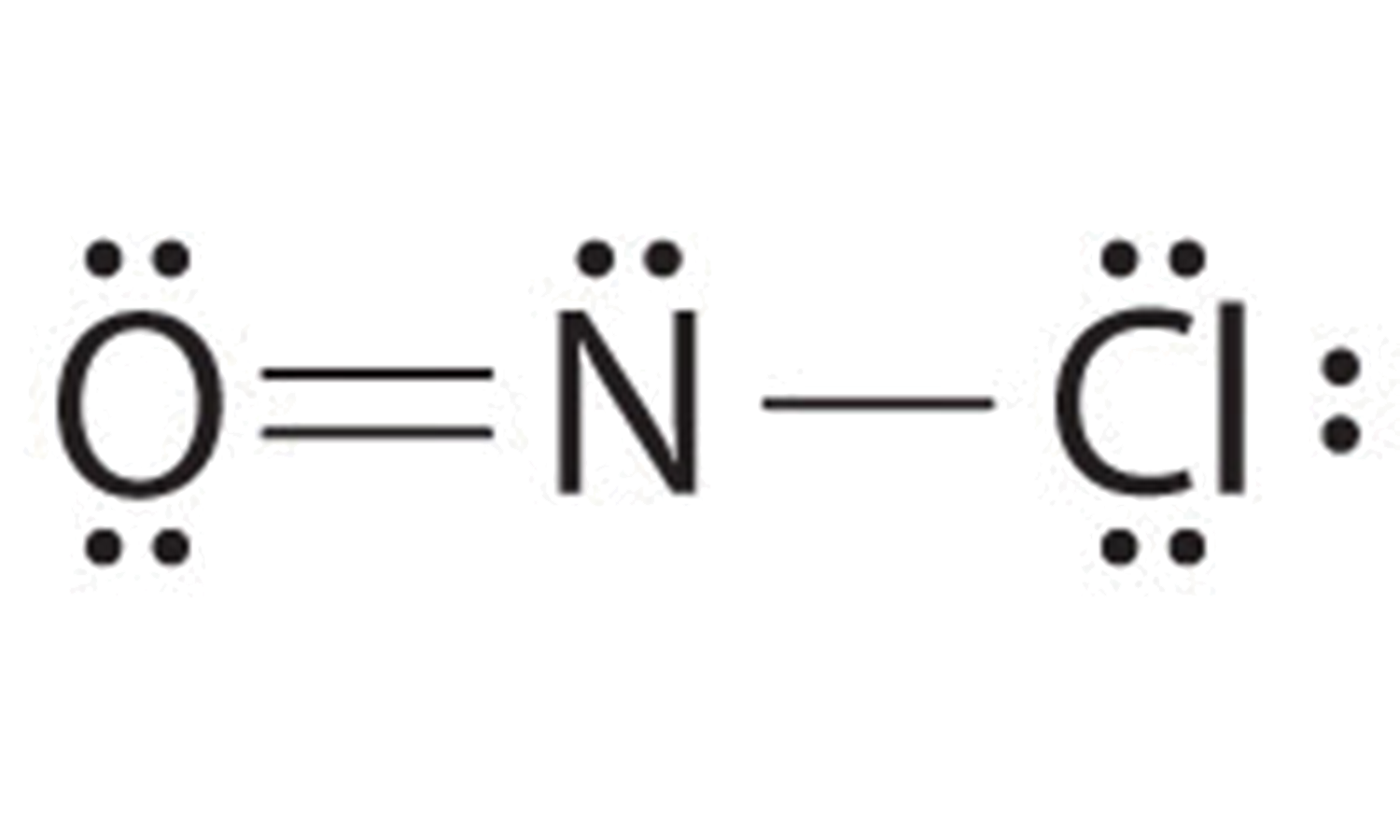

Adding three lone pairs each to oxygen and to chlorine uses 12 more electrons, leaving 2 electrons to place as a lone pair on nitrogen:

Because this Lewis structure has only 6 electrons around the central nitrogen, a lone pair of electrons on a terminal atom must be used to form a bonding pair. We could use a lone pair on either O or Cl. Because we have seen many structures in which O forms a double bond but none with a double bond to Cl, it is reasonable to select a lone pair from O to give the following:

All

atoms

now have octet configurations. This is the Lewis electron structure of nitrosyl chloride, a highly corrosive, reddish-orange gas.

Exercise 9.5.19.5.1

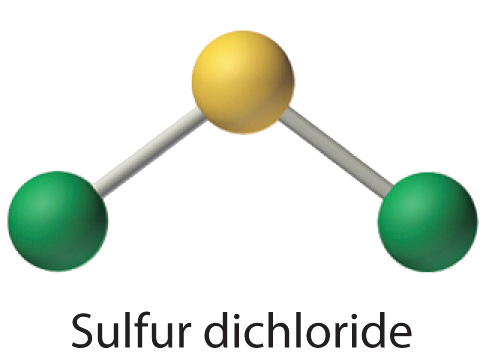

Write Lewis electron structures for CO2 and SCl2, a vile-smelling, unstable red liquid that is used in the manufacture of rubber.

Answer

Two chlorines are bonded to a sulfur. The sulfur has 2 lone pairs while the chlorines have 3 lone pairs each.

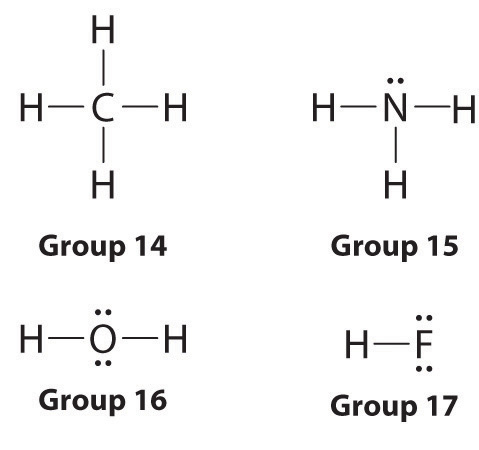

Using Lewis Electron Structures to Explain Stoichiometry

Lewis dot symbols provide a simple rationalization of why elements form compounds with the observed stoichiometries. In the Lewis model, the number of bonds formed by an element in a neutral compound is the same as the number of unpaired electrons it must share with other

atoms

to complete its octet of electrons. For the elements of Group 17 (the halogens), this number is one; for the elements of Group 16 (the

), it is two; for Group 15 elements, three; and for Group 14 elements four. These requirements are illustrated by the following Lewis structures for the hydrides of the lightest members of each group:

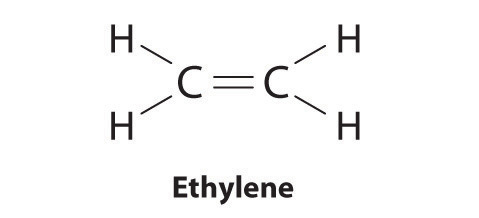

Elements may form multiple bonds to complete an octet. In ethylene, for example, each carbon contributes two electrons to the double bond, giving each carbon an octet (two electrons/bond × four bonds = eight electrons). Neutral structures with fewer or more bonds exist, but they are unusual and violate the

octet rule

.

Allotropes of an element can have very different physical and

chemical properties

because of different three-dimensional arrangements of the

atoms

; the number of bonds formed by the component

atoms

, however, is always the same. As noted at the beginning of the chapter, diamond is a hard, transparent solid; graphite is a soft, black solid; and the fullerenes have open cage structures. Despite these differences, the carbon

atoms

in all three allotropes form four bonds, in accordance with the

octet rule

.

Lewis structures explain why the elements of groups 14–17 form neutral compounds with four, three, two, and one bonded atom(s), respectively.

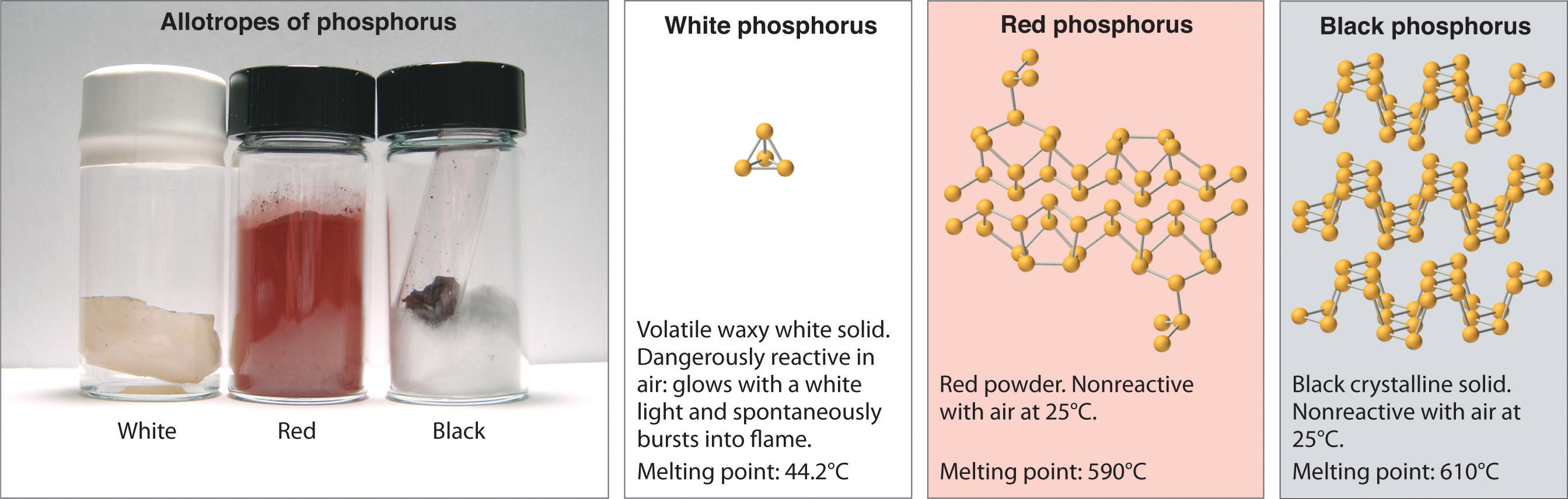

Elemental phosphorus also exists in three forms: white phosphorus, a toxic, waxy substance that initially glows and then spontaneously ignites on contact with air; red phosphorus, an amorphous substance that is used commercially in safety matches, fireworks, and smoke bombs; and black phosphorus, an unreactive crystalline solid with a texture similar to graphite (Figure 9.5.39.5.3). Nonetheless, the phosphorus

atoms

in all three forms obey the

octet rule

and form three bonds per phosphorus atom.

Figure 9.5.39.5.3: The Three Allotropes of Phosphorus: White, Red, and Black. ll three forms contain only phosphorus

atoms

, but they differ in the arrangement and connectivity of their

atoms

. White phosphorus contains P4 tetrahedra, red phosphorus is a network of linked P8 and P9 units, and black phosphorus forms sheets of six-membered rings. As a result, their physical and

chemical properties

differ dramatically.

Formal Charges

It is sometimes possible to write more than one Lewis structure for a substance that does not violate the

octet rule

, as we saw for CH2O, but not every Lewis structure may be equally reasonable. In these situations, we can choose the most stable Lewis structure by considering the

formal charge

on the

atoms

, which is the difference between the number of

valence electrons

in the free atom and the number assigned to it in the Lewis electron structure. The

formal charge

is a way of computing the charge distribution within a Lewis structure; the sum of the formal charges on the

atoms

within a molecule or an ion must equal the overall charge on the molecule or ion. A

formal charge

does not represent a true charge on an atom in a

covalent bond

but is simply used to predict the most likely structure when a compound has more than one valid Lewis structure.

To calculate formal charges, we assign electrons in the molecule to individual

atoms

according to these rules:

Nonbonding electrons are assigned to the atom on which they are located.

Bonding electrons are divided equally between the bonded

atoms

.

For each atom, we then compute a

formal charge

:

fo

r

malcha

r

ge=valencee−−(f

r

eeatom)(non−bondinge−+bondinge−2)(atominLewisst

r

uctu

r

e)𝑓𝑜

𝑟

𝑚𝑎𝑙𝑐ℎ𝑎

𝑟

𝑔𝑒=𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑒−−(𝑛𝑜𝑛−𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−+𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−2)(𝑓

𝑟

𝑒𝑒𝑎𝑡𝑜𝑚)(𝑎𝑡𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑛𝐿𝑒𝑤𝑖𝑠𝑠𝑡

𝑟

𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑢

𝑟

𝑒) (atom in Lewis structure)

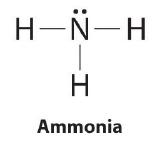

To illustrate this method, let’s calculate the

formal charge

on the

atoms

in ammonia (NH3) whose Lewis electron structure is as follows:

A neutral nitrogen atom has five

valence electrons

(it is in group 15). From its Lewis electron structure, the nitrogen atom in ammonia has one lone pair and shares three bonding pairs with hydrogen

atoms

, so nitrogen itself is assigned a total of five electrons [2 nonbonding e− + (6 bonding e−/2)]. Substituting into Equation 9.5.19.5.1, we obtain

fo

r

malcha

r

ge(N)=5valencee−−(2non−bondinge−+6bondinge−2)=0(9.5.1)(9.5.1)𝑓𝑜

𝑟

𝑚𝑎𝑙𝑐ℎ𝑎

𝑟

𝑔𝑒(𝑁)=5𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑒−−(2𝑛𝑜𝑛−𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−+6𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−2)=0

A neutral hydrogen atom has one valence electron. Each hydrogen atom in the molecule shares one pair of bonding electrons and is therefore assigned one electron [0 nonbonding e− + (2 bonding e−/2)]. Using Equation 9.5.19.5.1 to calculate the

formal charge

on hydrogen, we obtain

fo

r

malcha

r

ge(H)=1valencee−−(0non−bondinge−+2bondinge−2)=0(9.5.2)(9.5.2)𝑓𝑜

𝑟

𝑚𝑎𝑙𝑐ℎ𝑎

𝑟

𝑔𝑒(𝐻)=1𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑒−−(0𝑛𝑜𝑛−𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−+2𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑒−2)=0

The hydrogen

atoms

in ammonia have the same number of electrons as neutral hydrogen

atoms

, and so their

formal charge

is also zero. Adding together the formal charges should give us the overall charge on the molecule or ion. In this example, the nitrogen and each hydrogen has a

formal charge

of zero. When summed the overall charge is zero, which is consistent with the overall charge on the NH3 molecule.

An atom, molecule, or ion has a

formal charge

of zero if it has the number of bonds that is typical for that species.

Typically, the structure with the most charges on the

atoms

closest to zero is the more stable Lewis structure. In cases where there are positive or negative formal charges on various

atoms

, stable structures generally have negative formal charges on the more electronegative

atoms

and positive formal charges on the less electronegative

atoms

. The next example further demonstrates how to calculate formal charges.

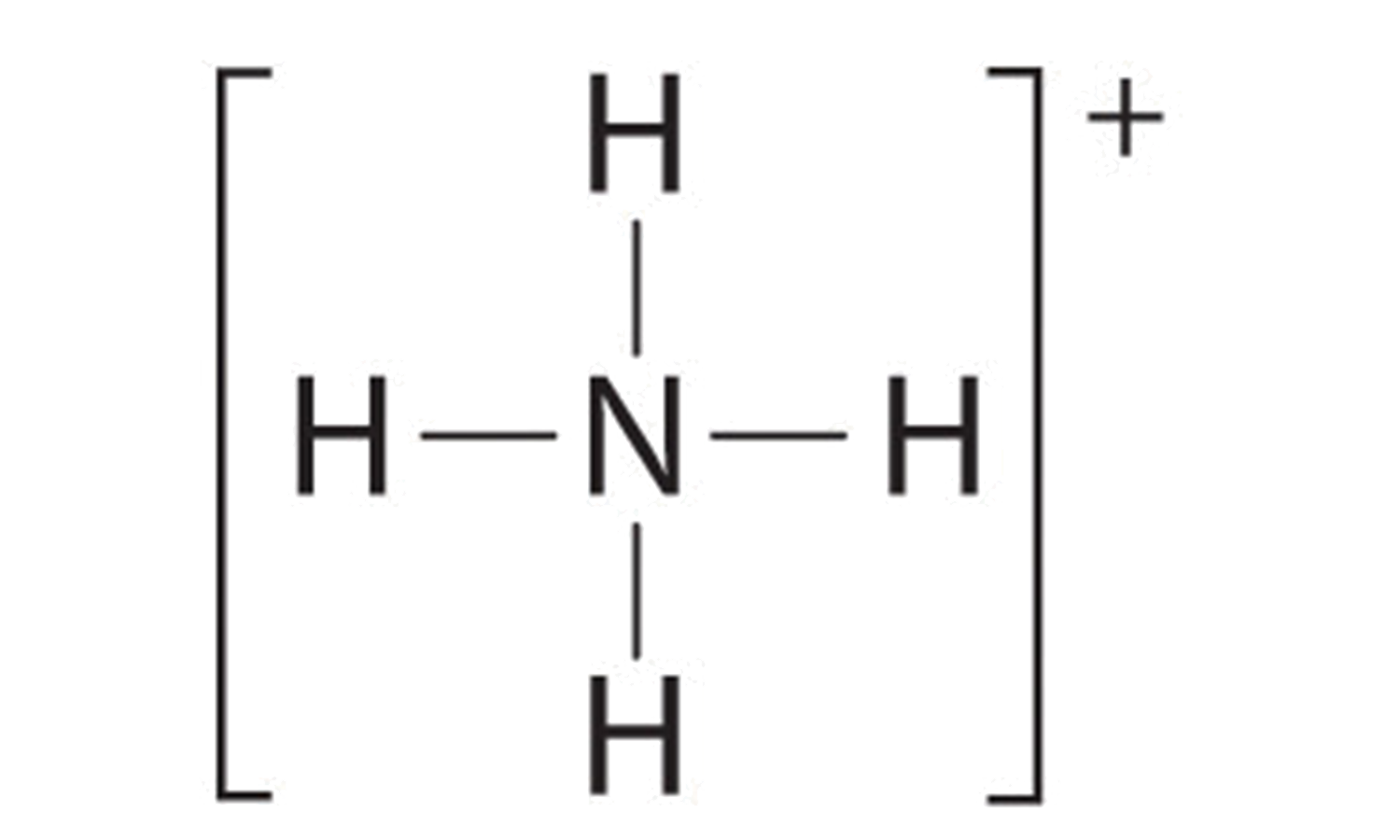

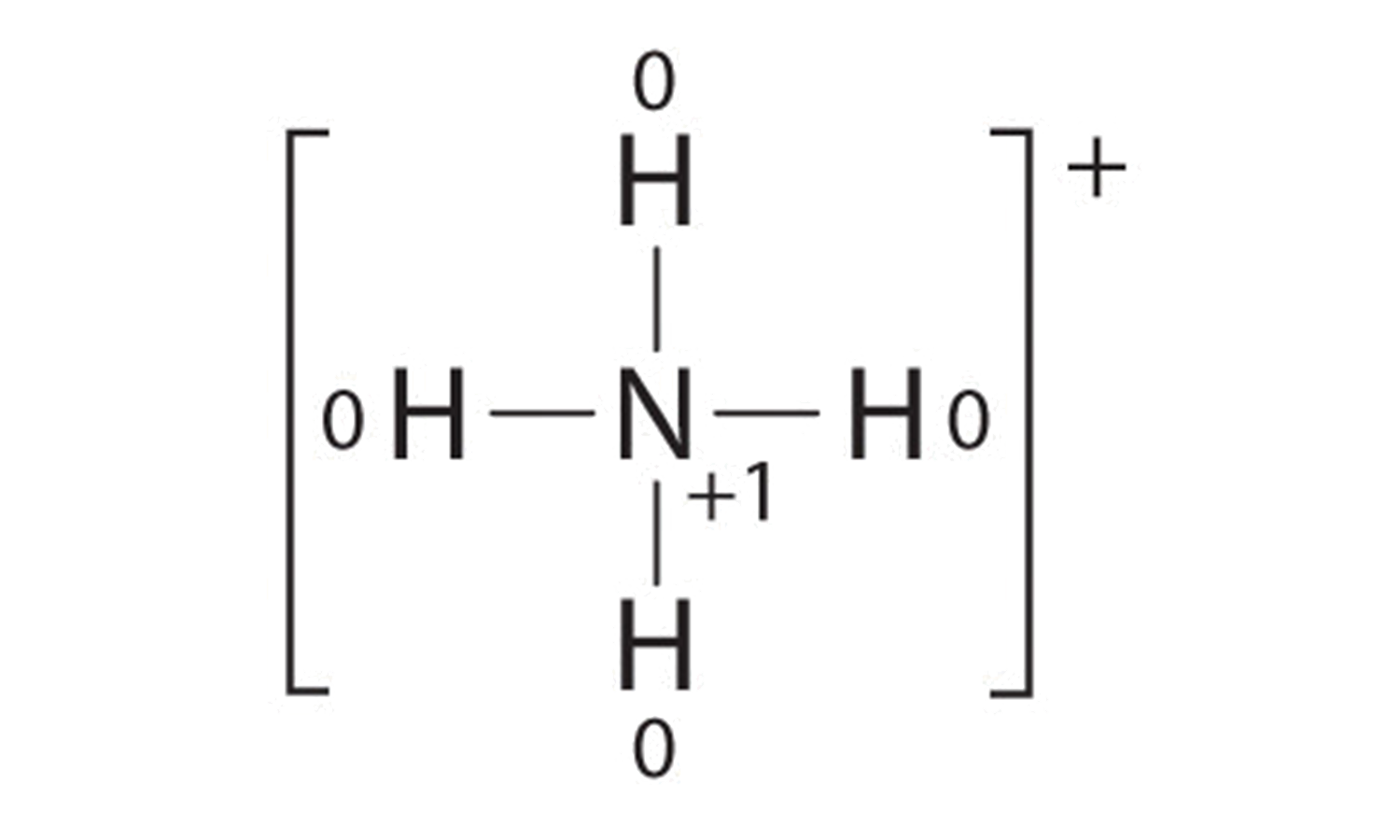

Example 9.5.29.5.2: The Ammonium Ion

Calculate the formal charges on each atom in the NH4+ ion.

Given: chemical species

Asked for: formal charges

Strategy:

Identify the number of

valence electrons

in each atom in the NH4+ ion. Use the Lewis electron structure of NH4+ to identify the number of bonding and nonbonding electrons associated with each atom and then use Equation 9.5.19.5.1 to calculate the

formal charge

on each atom.

Solution:

The Lewis electron structure for the NH4+ ion is as follows:

The central nitrogen is bonded to four hydrogens. The molecule is surrounded by square brackets. Outside the bracket is where the positive charge is placed.

The nitrogen atom shares four bonding pairs of electrons, and a neutral nitrogen atom has five

valence electrons

. Using Equation ??????, the

formal charge

on the nitrogen atom is therefore

fo

r

malcha

r

ge(N)=5−(0+82)=0𝑓𝑜

𝑟

𝑚𝑎𝑙𝑐ℎ𝑎

𝑟

𝑔𝑒(𝑁)=5−(0+82)=0

Each hydrogen atom in has one bonding pair. The

formal charge

on each hydrogen atom is therefore

fo

r

malcha

r

ge(H)=1−(0+22)=0𝑓𝑜

𝑟

𝑚𝑎𝑙𝑐ℎ𝑎

𝑟

𝑔𝑒(𝐻)=1−(0+22)=0

The formal charges on the

atoms

in the NH4+ ion are thus

In the Lewis structure, each hydrogen has a zero placed nearby while the nitrogen has a +1 placed nearby.

Adding together the formal charges on the

atoms

should give us the total charge on the molecule or ion. In this case, the sum of the formal charges is 0 + 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 = +1.

Exercise 9.5.29.5.2

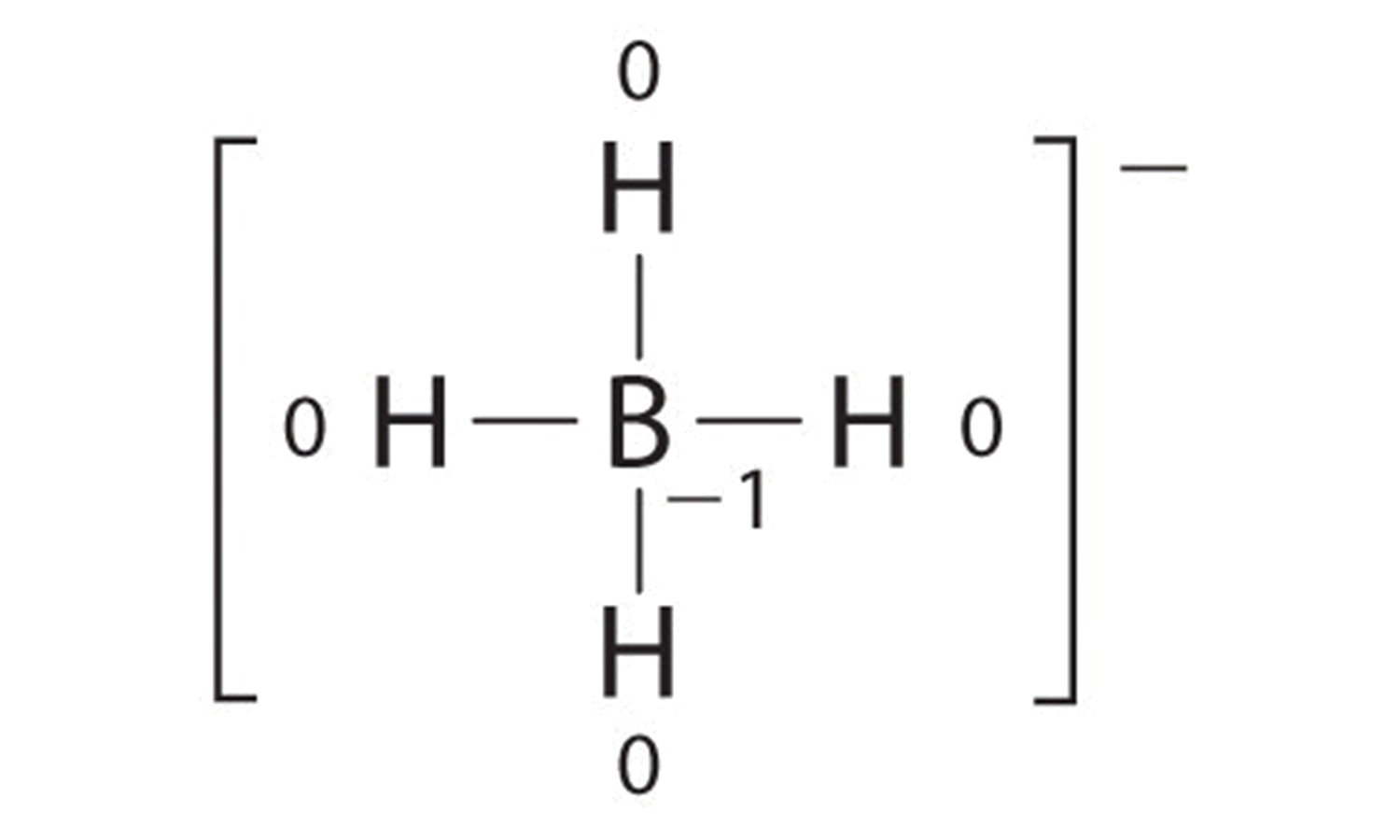

Write the formal charges on all

atoms

in BH4−.

Answer

Four hydrogens are bonded to a central boron. Each hydrogen has a zero placed nearby while the boron has a -1. The molecule is surrounded by square brackets. Outside of the brackets is a negative charge.

If an atom in a molecule or ion has the number of bonds that is typical for that atom (e.g., four bonds for carbon), its

formal charge

is zero.