The search for criminological explanation

A word on theory and explanations

Introduction to Criminological Theory

Definition of Theory:

Theory refers to a set of ideas, assumptions, or hypotheses that help us make sense of the world. It helps us explain complex social phenomena like crime.

In criminology, theory is designed to explain why some individuals engage in criminal behavior, and others do not, beyond individual experiences or anecdotes. It is distinguished from "common sense," which often works in specific contexts but may not provide a generalizable explanation.

Criminological Theory vs. Common Sense:

Common sense is often based on personal experiences and assumptions. It works in specific situations but fails to explain crime at a broader, societal level.

Criminological theory attempts to explain crime through generalizable principles, focusing on underlying patterns, trends, and behaviors.

Importance of Theory:

Criminologists seek theories that can offer broad, general explanations of crime, going beyond anecdotal evidence.

Policy implications: Theories of crime help shape policies. To evaluate a theory, we need to understand how it applies to crime, society, and criminal justice practices.

Key Questions to Understand Criminological Theory

To make sense of criminological theory, it is useful to ask the following questions:

What is the theory trying to explain, and what aspects does it ignore?

This helps identify the scope and limitations of a theory. Some theories might focus on particular types of crime or social groups, while ignoring others.

How can we categorize this theory?

Schools of thought: Theoretical frameworks can be categorized under different schools like classical, positivist, or critical criminology.

Key concepts and ideas: These include terms like social control, rational choice, relative deprivation, etc.

Main theorists: Understanding the key figures who developed the theory is essential for context.

When and where was the theory written?

The historical and social context in which the theory was developed is crucial, as it can affect its relevance and focus.

What are the policy implications that flow from the theory?

Theories often suggest specific policy interventions, such as reforming the justice system, changing laws, or addressing root social causes.

How do those implications resonate with the political climate of the time?

The application of criminological theory is often influenced by the political climate and public sentiment of the time. What is considered "effective" or "appropriate" can change depending on broader societal issues.

How does the theory relate to the evidence?

A good theory should align with empirical evidence and help explain observable patterns in crime, criminal behavior, and victimization.

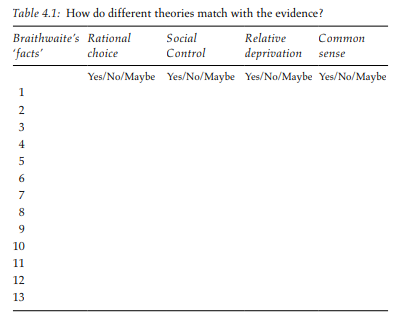

John Braithwaite's 13 Facts About Crime

John Braithwaite (1989) outlined 13 facts that criminology needs to explain. These facts include patterns of criminal behavior and social factors that influence crime. Braithwaite's facts are:

Disproportionate crime rates by gender: Crime is predominantly committed by males.

Age factor: Crime is more common among 15–25-year-olds.

Marital status: Unmarried individuals are more likely to commit crimes.

Urban living: People in large cities are more likely to engage in criminal behavior.

Residential mobility: Those with high residential mobility or in areas with high turnover are more likely to commit crimes.

School attachment: Young people attached to school are less likely to engage in crime.

Educational and occupational aspirations: Young people with high aspirations are less likely to engage in crime.

School performance: Poor school performance correlates with higher likelihood of criminal behavior.

Parental attachment: Strong attachment to parents is associated with lower crime involvement.

Criminal peer influence: Friendships with criminals increase the likelihood of committing crime.

Belief in the law: Those who believe in obeying the law are less likely to offend.

Class and ethnicity: Lower social class and ethnic minorities are more likely to offend, except in crimes where opportunities are systematically less available to the poor.

Crime trends: Crime rates have generally been increasing since WWII, except in Japan.

Evaluating Criminological Theories

The following are key questions to evaluate criminological theories in relation to the facts above:

What kind of crime is the theory trying to explain?

Is it focused on violent crimes, property crimes, or white-collar crimes?

Does it focus on specific demographics like youth or marginalized communities?

Where does the theory fit in relation to ideas of the time?

Is the theory in line with mainstream sociological or psychological ideas?

Does it reflect the dominant political or cultural context in its time of development?

When and where was the theory written?

What historical events or social conditions might have influenced the theory's creation?

Was it written in a period of high crime rates, social unrest, or political shifts?

What policies flow from the theory?

Does the theory suggest punitive measures, rehabilitative approaches, or preventive strategies?

What kind of justice system reforms or social interventions might the theory advocate for?

How does it relate to the evidence?

Does the theory align with or explain statistical crime trends and empirical research?

Can it predict patterns of crime and victimization effectively?

Four Criminological Explanations to Illustrate Theory and Policy

The following criminological theories are commonly discussed in criminological research and are useful in exploring the link between theory, evidence, and policy.

Rational Choice Theory

Explanation: Crime is viewed as the result of a rational decision-making process where the offender weighs the potential rewards against the risks of getting caught.

Policy Implication: Policies may include deterrence strategies, such as increasing penalties for crime or improving surveillance systems to reduce opportunities for crime.

Criticism: This theory overlooks the social, psychological, and economic factors that may influence criminal behavior.

Social Control Theory

Explanation: Proposes that crime occurs when an individual's bonds to society (e.g., family, school, community) are weakened. Strong social ties prevent criminal behavior.

Policy Implication: Strengthening community programs, promoting family-based interventions, and enhancing educational opportunities to build social bonds.

Criticism: It may not explain why people without strong social bonds engage in crime.

Relative Deprivation Theory

Explanation: Crime results from the feeling of being deprived compared to others, often linked to economic disparity and social inequality.

Policy Implication: Policies focused on reducing social inequality, enhancing social services, and addressing poverty.

Criticism: The theory may not account for individuals who do not resort to crime despite feeling deprived.

Hegemonic Masculinity Theory

Explanation: Crime, especially violent crime, is seen as a product of societal norms of masculinity that emphasize aggression, dominance, and control.

Policy Implication: Policies could focus on gender equality, violence prevention programs, and challenging traditional gender roles in education and media.

Criticism: The theory may overemphasize the role of masculinity in crime without adequately considering other factors like class, race, or psychological conditions.

Conclusion

Criminological theory is vital in helping us understand crime at a societal level and offers policy solutions that can address its root causes.

To evaluate the usefulness and relevance of a theory, it's essential to consider the type of crime it addresses, its social context, its policy implications, and how well it aligns with empirical evidence.

Theories like rational choice theory, social control theory, relative deprivation, and hegemonic masculinity illustrate the complex relationship between theory, evidence, and policy, showing how each theory can lead to distinct approaches to crime prevention and justice reform.

Rational Choice Theory

Rational Choice Theory (RCT) is a criminological theory that emphasizes the decision-making process of offenders, asserting that criminals are rational actors who weigh the costs and benefits of committing crime before taking action. The theory draws on classical criminology, which portrays individuals as beings motivated by the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. This theory assumes that offenders make decisions based on available information and make choices that they perceive will benefit them.

Key Points of Rational Choice Theory:

Decision-Making Process: Offenders are seen as rational actors who weigh the costs (risks) against the benefits (rewards) of committing a crime. This includes practical considerations such as the time of day, the presence of surveillance, or the ease of the crime.

Economic Analogy: In classical criminology, individuals are assumed to act like rational economic agents, calculating the potential rewards and punishments associated with their actions.

Revival in the 1980s: Rational choice theory experienced a resurgence in the 1980s, partly due to the rising crime rates and the desire for new crime prevention strategies.

Bounded Rationality: Although offenders are seen as rational, their decision-making is limited by the information they have and the circumstances surrounding the crime. This is termed "bounded rationality."

Purposeful Crime: Crime is always purposive, meaning that criminals commit crimes with the intention of benefiting themselves, whether it's through financial gain, social status, or some other form of reward.

Routine Activity Theory (RAT)

Routine Activity Theory, closely linked to rational choice theory, focuses on the conditions that enable crime. It argues that crime is the result of three elements coming together in time and space:

Motivated Offender: A person who is inclined to commit a crime.

Suitable Target: A person or object that the offender sees as a target for crime.

Absence of Capable Guardian: A person or mechanism that would prevent or discourage the crime (e.g., police, surveillance cameras, or vigilant bystanders).

Key Concepts:

Crime as an Event: Crime is not viewed as a singular, abstract event, but as something that occurs when these three elements align.

Predicting Crime: Routine Activity Theory helps predict when and where crime is likely to occur by analyzing patterns in individuals' daily activities.

Link to Victimization: This theory also provides insight into patterns of victimization. People who engage in certain activities (e.g., staying out late, visiting dangerous neighborhoods) are at higher risk of becoming victims of crime.

Crime Prevention:

Situational Crime Prevention (SCP): Both Rational Choice and Routine Activity Theory inform crime prevention strategies that focus on reducing opportunities for crime. These strategies aim to make crimes harder to commit by altering the environment or the situation.

Target Hardening: This involves making potential crime targets more difficult to access or harm (e.g., installing security systems or locks).

Increased Guardianship: This refers to increasing the presence of capable guardians (e.g., police patrols, surveillance cameras).

Reducing Opportunities: The core idea is that if the opportunity for crime is eliminated or reduced, criminals will be discouraged from committing crimes due to the higher perceived costs.

Example: The use of closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in public spaces is a direct application of situational crime prevention policies informed by Rational Choice and Routine Activity Theory.

Limitations of Rational Choice Theory:

Displacement: One critique of Rational Choice Theory and situational crime prevention is the concept of crime displacement. When crime is made more difficult in one area, offenders may simply move to other areas or commit different types of crime. This highlights the limitations of situational crime prevention as a sole solution to crime.

Overemphasis on Rationality: RCT tends to oversimplify human behavior by assuming all offenders make purely rational decisions. In reality, factors like emotions, social pressures, or mental health issues may influence criminal behavior.

Complexity of Offender Decision-Making: RCT assumes that all offenders engage in a similar process of decision-making, but this fails to account for the diversity in offenders' motivations and circumstances.

Policy Implications of Rational Choice and Routine Activity Theories:

Focus on the Environment: Since these theories emphasize opportunity and environmental factors, policies inspired by these theories tend to focus on altering the physical and social environment to prevent crime.

Situational Crime Prevention: Practical interventions include better lighting, increased police presence, improved urban design (e.g., defensible space), and promoting social cohesion (e.g., neighborhood watch programs).

Crime Science:

Definition: Crime science is an interdisciplinary approach that combines criminology with a scientific approach to problem-solving, particularly focusing on the environmental factors influencing crime.

Empirical Testing: Crime science emphasizes the need for empirical research, data analysis, and experimentation to test hypotheses about crime prevention.

Focus on Immediate Contexts: It examines the immediate circumstances surrounding criminal behavior, such as the rewards of crime, the environmental context, and the opportunities available for crime.

Influence of Crime Science: Crime science seeks to apply the principles of rational choice and routine activity theories to practical crime prevention. It works to understand patterns of criminal activity, identify "hot spots," and determine effective interventions.

Political Context – Right Realism:

Political Influence: Rational choice theory, routine activity theory, and situational crime prevention were influential in shaping policies in the 1980s, particularly under the "right realism" paradigm. Right realism focuses on individual responsibility and emphasizes that crime is an issue caused by individual choices, rather than societal factors.

Criticism of Social Structural Causes: Right realism, associated with these theories, tends to downplay the importance of broader social structures (e.g., inequality, poverty) in explaining crime, instead focusing on individual choices and opportunities.

Conclusion:

Rational Choice Theory, together with Routine Activity Theory and Crime Science, provides a framework for understanding criminal behavior in terms of decision-making, opportunity, and environmental factors. These theories have significantly influenced crime prevention strategies, particularly situational crime prevention, which focuses on reducing opportunities for crime. While these theories offer valuable insights, they also face criticism for oversimplifying human behavior and failing to account for the broader social causes of crime. Additionally, the issue of crime displacement raises questions about the long-term effectiveness of such approaches.

Social control theory

Overview: Social control theory is distinct from rational choice theory in its focus and approach to crime. While rational choice theory emphasizes individual decision-making and the calculation of risks and rewards in committing a crime, social control theory examines how societal structures, institutions, and relationships encourage individuals to conform to social norms and laws. It is concerned more with understanding why people obey societal rules rather than why they break them.

Key Focus Areas of Social Control Theory:

Focus on Social Processes:

Social control theory concentrates on the influence of society and its institutions on individual behavior. It seeks to explain how society instills law-abiding behavior.

The theory looks at how social relationships and social norms influence individuals to conform, rather than focusing solely on individual motivations to deviate.

Fear and Motivation:

Social control theory places fear at the center of human motivation for conforming to social rules, in contrast to the rational choice theory's focus on maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain.

The theory is grounded in the idea expressed by philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1651) that without societal controls, life would be a "war of every man against every man."

Hobbes’ View: Fear of punishment is what compels individuals to obey the law, especially when breaking the law might seem to offer personal benefit.

Hirschi's Social Bond Theory (1969): One of the most well-known formulations of social control theory is developed by Travis Hirschi. He proposed that social bonds prevent individuals from engaging in criminal behavior. There are four components of social bonds:

Attachment:

Refers to the strength of an individual's relationships with others (e.g., family, friends, teachers).

The stronger the attachment, the greater the influence of social expectations, making it more likely for individuals to conform to societal norms.

Example: An individual with strong ties to family and community is less likely to commit a crime.

Commitment:

Refers to the individual's investment in conventional activities (e.g., education, career, family).

The more committed an individual is to a conventional lifestyle, the more they have to lose if they engage in criminal activity.

Example: A person who is dedicated to a successful career is less likely to risk it by committing a crime.

Involvement:

Refers to the amount of time an individual spends in conventional activities.

The more time spent engaged in lawful behavior (e.g., work, school), the less time there is for deviant or criminal activities.

Example: A busy individual involved in community activities or working full-time has less opportunity to engage in criminal behavior.

Belief:

Refers to an individual's adherence to societal norms and laws.

People who believe in the values of society (e.g., honesty, fairness) are less likely to violate laws.

Example: A person raised with strong moral values is less likely to break the law.

Interconnections Among Social Bonds:

Hirschi's four elements of social bonds are interdependent. For instance, a person who is committed to a conventional lifestyle (commitment) will likely have strong attachments to others (attachment), be involved in social activities (involvement), and hold beliefs that align with societal norms (belief).

The idea aligns with common-sense concepts like "idle hands are the devil’s workshop," where a lack of involvement leads to deviant behavior.

Empirical Support and Criticisms:

Empirical Support: Hirschi's social bond theory has been empirically tested and has received significant support, especially regarding the role of attachment and commitment in preventing crime.

Criticisms:

Lack of Explanation for Different Crimes:

Social control theory struggles to explain why the absence of control leads some people to engage in specific crimes (e.g., drug use) and others to engage in different crimes (e.g., tax fraud).

It also does not explain why some people engage in deviant behavior despite having strong social bonds.

Overemphasis on Social Bonds:

The theory doesn't adequately address the social context in which law-breaking behavior is defined and labeled, such as why some individuals' actions are deemed criminal while others' are not.

Gottfredson and Hirschi's General Theory of Crime (1991):

Combination of Social Control and Rational Choice Theory:

Gottfredson and Hirschi refined social control theory by incorporating the concept of self-control, arguing that individuals with low self-control are more prone to criminal behavior, regardless of social bonds.

They suggested that ineffective parenting leads to the development of low self-control, which in turn increases the likelihood of deviant behavior.

This theory emphasizes that a lack of self-control is central to understanding criminal behavior.

Limitations:

Critics argue that the theory is too simplistic in explaining all types of crimes, especially white-collar crimes or crimes committed by individuals with high self-control.

Charles Tittle’s Control Balance Theory (1995):

Concept of Control Balance:

Tittle introduced the idea that both too little control and too much control can lead to deviant behavior.

Control Balance: A balance of control—neither too much nor too little—is essential for maintaining conformity.

If control is imbalanced, deviance occurs. This imbalance may arise from various factors, such as excessive control or insufficient control over an individual’s actions.

Elements for Deviant Behavior:

Predisposition for Deviant Behavior: Motivation to engage in crime.

Trigger Mechanism: A situation or event that reveals the imbalance in control.

Recognition of Opportunity: The recognition of a chance to engage in deviant behavior.

Ability to Overcome Constraints: The capacity to bypass moral, situational, or social constraints that prevent criminal behavior.

Integration with Other Theories:

Tittle’s work combines elements from rational choice theory and social control theory, considering both individual predispositions and social constraints.

Impact and Policy Implications:

Social Control Theory’s Subtle Impact on Policy:

Social control theory has had a more nuanced influence on policy. It highlights the importance of social relationships, family dynamics, and socialization processes in preventing crime.

However, its focus on social relationships and long-term processes makes it difficult to implement quick and measurable interventions, especially in policy contexts that demand immediate solutions.

Parenting as a Key Intervention:

Interventions based on this theory often focus on improving parenting and family dynamics, as effective parenting is seen as crucial in developing self-control in children.

However, such interventions can be complex and difficult to evaluate in terms of immediate effectiveness.

Conclusion: Social control theory provides a framework for understanding how societal influences and relationships can prevent crime by encouraging conformity. It emphasizes the importance of attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief in maintaining social order. However, it faces criticisms for its limited scope in explaining all forms of deviance and for being overly simplistic in its reliance on social bonds and self-control. The development of related theories, such as Tittle's control balance theory and Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime, has expanded the understanding of criminal behavior by integrating additional factors like self-control and control imbalance.

Relative deprivation

Overview of Relative Deprivation

Definition (Walklate, 2007: 61): Relative deprivation refers to situations where people may not be objectively deprived (i.e., in absolute terms), but they feel deprived due to comparing themselves to others, either within the same social category or across different social categories. It is a subjective feeling of deprivation rather than an objective reality.

Historical Context: The concept of relative deprivation has its roots in social psychology but was later adapted to criminology, particularly within the framework of left realism.

Relative Deprivation in Criminology:

Jock Young's Contribution: A key figure in integrating relative deprivation into criminology, Young argues that the concept is vital for understanding crime. He identifies three reasons why relative deprivation is a powerful explanatory tool in criminology:

Universality: It can be applied to a wide range of crimes, not just those driven by economic motivations.

No Need for Absolute Standards: Unlike traditional theories, relative deprivation does not require an absolute threshold of poverty or lack of resources. It is based on perception and comparison.

Focus on Perception: It emphasizes how people perceive their position in society in comparison to others, particularly in terms of fairness or inequality, which can lead to discontent and, ultimately, crime.

Left Realism and the Role of Relative Deprivation:

Background: Left realism emerged in the UK during the 1980s in response to crime surveys that downplayed the actual impact of crime in people's lives. The aim was to bring attention to the real, everyday experiences of crime.

Political Purpose: While left realism has a political agenda to challenge mainstream views on crime, it also strives to be more than just political rhetoric. It attempts to provide a detailed and accurate understanding of crime and its impact.

The 'Square of Crime': To fully understand crime, left realism emphasizes the need to consider four key elements:

The victim of crime.

The offender committing the crime.

The reaction of formal agencies of the state (police, courts, etc.).

The reaction of the public and how these elements interact.

Relative Deprivation in the Square of Crime: Relative deprivation is crucial for understanding how crime is shaped by social perceptions. The motivation for criminal behavior arises from the discontent individuals feel when they perceive their situation as unfair, particularly when comparing their circumstances to others.

Young's View on Crime and Social Structure:

Discontent Across the Social Structure: According to Jock Young (2001: 244), discontent can occur anywhere within the class structure, not just in marginalized groups. It stems from individuals perceiving their rewards as unjust when compared to others with similar characteristics.

Example: Professional athletes’ high salaries or bankers' bonuses (even in the wake of economic crises) can evoke feelings of relative deprivation across both rich and poor sections of society.

Crime and Relative Deprivation:

Not Just Material Deprivation: Young argues that while material deprivation is linked to crime, it is not the sole cause. Instead, the issue lies in the social order and the perception of unfairness.

Crisis of Identity: Relative deprivation can lead to a crisis of identity, affecting people’s sense of worth and leading to various forms of social unrest or criminal behavior.

Policy Implications of Left Realism:

Multi-Agency Interventions: Left realism emphasizes the importance of multi-agency approaches to crime prevention. These have become common in the UK, where agencies work together to address the root causes of crime, especially in vulnerable communities.

Focus on the Most Vulnerable: Policies derived from left realism often focus on those most affected by crime, acknowledging that crime disproportionately impacts socially excluded individuals or communities.

Key Criticism of Relative Deprivation:

The Paradox of Crime: A key criticism arises from the following question:

Why do some people, who feel relatively deprived like their neighbors, turn to crime, while others do not?

This question points to a central issue in criminology: Is crime due to individual choices and characteristics, or does society play a bigger role in shaping behavior? In other words, does relative deprivation alone explain crime, or is it a combination of personal, social, and economic factors?

Individual vs. Societal Responsibility: This question highlights the debate between theories that focus on individual responsibility versus those that emphasize social and structural factors in explaining criminal behavior. The challenge remains in determining the precise role of relative deprivation within the broader picture of crime causation.

Evaluating Left Realism and Relative Deprivation:

Link to Social Inequality: Left realism acknowledges that relative deprivation is closely connected to broader issues of social inequality. However, it does not claim that inequality alone leads to crime. Instead, it views crime as a product of both social conditions and individual perceptions.

Crime as a Social Construct: Left realists argue that crime cannot be solely understood through material deprivation. Instead, it must be seen as a socially constructed problem, with the perceptions and responses of the public and formal agencies playing a crucial role in its perpetuation.

Conclusion:

Relative Deprivation remains an important concept in criminology, especially within the context of left realism. It helps explain how perceptions of inequality and unfairness can lead to criminal behavior, regardless of an individual’s material circumstances.

However, its application remains complex. While relative deprivation can explain why people feel discontent and perceive a need for change, it does not explain why some individuals engage in crime while others in similar circumstances do not. This leads to ongoing debates about the individual vs. societal factors in crime causation and the role of social perceptions in shaping behavior.

How do these different theories perform in relation to the evidence

Introduction

Theories of Crime: Theories of crime aim to explain why people engage in criminal behavior. These theories are often evaluated based on their ability to account for empirical evidence.

Braithwaite’s 13 Facts: In evaluating criminological theories, John Braithwaite proposed a set of 13 facts that any theory of crime should be able to explain. These "facts" represent real-world patterns and trends in criminal behavior. These facts focus on the nature, causes, and impacts of crime. However, Braithwaite acknowledges that no single theory can explain all kinds of crime, and some theories might only fit specific categories of crime.

Key Task: This section focuses on evaluating how the theories of Social Control Theory, Relative Deprivation, and Rational Choice Theory perform in explaining these 13 facts.

Braithwaite’s 13 Facts

Crime is widely distributed in society.

Crime rates vary across groups and communities.

Crime tends to concentrate among the poor.

Criminals tend to engage in multiple kinds of crime.

Criminals often start young.

Offenders tend to commit crimes in groups.

Crime is associated with a lack of social bonds.

Crime is associated with social strain or frustration.

Crime can be a product of socialization.

Crime is often a rational decision.

Crime is often influenced by opportunity.

Crime is often a result of weak formal social controls.

Gender plays a significant role in criminal behavior.

Evaluation of Theories in Relation to Braithwaite’s Facts

1. Social Control Theory (Hirschi)

Social Bonds (Attachment, Commitment, Involvement, Belief): Social control theory focuses on the strength of an individual’s connection to societal norms and values.

Facts Explained:

Fact 7 (Crime is associated with a lack of social bonds): Social control theory directly explains this fact, as weak social bonds (attachment, commitment, involvement, belief) increase the likelihood of criminal behavior.

Fact 12 (Crime is often a result of weak formal social controls): This is addressed through the emphasis on the absence of strong social bonds or authority structures that promote law-abiding behavior.

Facts Left Unexplained:

Fact 10 (Crime is often a rational decision): Social control theory focuses more on the socialization process rather than on rational choice or decision-making.

Fact 11 (Crime is often influenced by opportunity): Social control theory doesn’t necessarily account for how the availability of opportunities shapes criminal behavior.

Fact 13 (Gender plays a significant role in criminal behavior): Social control theory doesn’t explicitly address gender differences in crime.

Key Strengths:

Provides a clear explanation for why people conform to societal norms and why they deviate when those bonds weaken.

Empirically supported, especially in understanding juvenile delinquency.

Key Weaknesses:

Doesn’t fully explain more complex crimes like corporate crime or insider trading.

Gender and opportunity factors are not emphasized.

2. Relative Deprivation Theory (Left Realism - Jock Young)

Social Comparison and Perception of Inequality: Relative deprivation theory explains how feelings of discontent, particularly in disadvantaged groups, can lead to criminal behavior when individuals perceive an unfair distribution of rewards.

Facts Explained:

Fact 2 (Crime rates vary across groups and communities): This is explained by relative deprivation, where discontentment in socially marginalized groups leads to higher crime rates.

Fact 3 (Crime tends to concentrate among the poor): Relative deprivation directly ties the feeling of deprivation to economic inequality, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

Fact 6 (Offenders often commit crimes in groups): Relative deprivation helps explain collective behavior, where groups with shared grievances may turn to crime as a collective response.

Fact 8 (Crime is associated with social strain or frustration): The theory connects social strain caused by inequality to criminal behavior.

Fact 9 (Crime can be a product of socialization): The sense of injustice and inequality learned in marginalized communities can encourage criminal behavior.

Facts Left Unexplained:

Fact 1 (Crime is widely distributed in society): Relative deprivation focuses more on the poor and excluded, so it might not explain crime in other, more affluent sectors.

Fact 7 (Crime is associated with a lack of social bonds): While social strain is explained, the theory does not emphasize how weak personal bonds lead to crime.

Fact 11 (Crime is influenced by opportunity): This theory focuses more on perception and inequality than on the actual opportunity for crime.

Key Strengths:

Strong in explaining crime in marginalized communities and groups.

Highlights the role of perceived inequality and injustice as drivers of crime.

Key Weaknesses:

Not all individuals in deprived communities engage in crime, so it fails to explain why some people do not act on feelings of deprivation.

Does not focus much on opportunity or the rational calculation of crime.

3. Rational Choice Theory

Rational Decision-Making: Rational Choice Theory explains crime as a result of individuals weighing the costs and benefits of criminal behavior.

Facts Explained:

Fact 10 (Crime is often a rational decision): This theory is based on the premise that crime is a rational choice made after considering the costs and benefits.

Fact 11 (Crime is often influenced by opportunity): The theory stresses that opportunities for crime (e.g., availability of targets or lack of guardianship) significantly impact whether an individual will engage in crime.

Facts Left Unexplained:

Fact 1 (Crime is widely distributed in society): Rational choice theory doesn’t explain why crime is prevalent across society; it focuses more on individual decisions.

Fact 2 (Crime rates vary across groups and communities): The theory doesn’t directly account for variations in crime based on social or economic groups.

Fact 3 (Crime tends to concentrate among the poor): The theory assumes crime occurs when opportunities arise, without necessarily focusing on social inequality.

Fact 7 (Crime is associated with a lack of social bonds): This theory does not focus on social relationships but on individual decision-making.

Fact 8 (Crime is associated with social strain or frustration): Rational choice theory does not emphasize strain or frustration as motivators for crime.

Key Strengths:

Offers a clear framework for understanding why individuals choose to engage in crime based on the costs and benefits.

Effective in explaining specific, planned crimes such as theft or fraud.

Key Weaknesses:

Doesn’t account for crimes driven by emotional or social factors, like impulsive crimes or crimes of passion.

Overemphasizes individual choice and neglects social contexts like inequality or lack of opportunity.

Comparison of Theories

Common Strengths:

Social Control Theory and Relative Deprivation both emphasize social bonds and social inequalities, though from different angles.

Rational Choice Theory and Relative Deprivation both acknowledge the importance of decision-making but in different contexts (rational decisions vs. perceived inequality).

Key Differences:

Social Control Theory: Focuses on social bonds and conformity. It lacks a strong emphasis on the material or economic conditions that contribute to crime.

Relative Deprivation Theory: Strong in explaining crime related to inequality but doesn’t account for individual decision-making or opportunity.

Rational Choice Theory: Focuses on individual decision-making and opportunity but neglects social context or structural factors.

Conclusion

Evidence Evaluation: While none of these theories perfectly fit all 13 of Braithwaite's facts, each offers valuable insights into different aspects of criminal behavior.

Missing Pieces: A comprehensive theory of crime would need to account for both individual and structural factors, including opportunity, inequality, social bonds, and rational decision-making. Gender and opportunity are key aspects that are not fully addressed by any one theory.

Comprehensive Understanding: The best approach likely involves integrating elements from multiple theories to explain the full range of criminal behavior across different contexts and groups.

Looking at the evidence: the question of gender

Introduction to Gender and Crime

Criminology and Victimology: Both fields have often highlighted some issues while sidelining others. One such issue is gender, which has had a complex relationship with how criminology theorizes crime and victimization.

The "Criminological Other" and "Victimological Other": These terms refer to the marginalization of certain groups (often women) in the study of crime and victimization. Gender issues have played a central role in constructing the "other" in criminological studies.

Male Dominance in Crime: Despite gender being an important factor in criminology, it is evident that crime is predominantly a male-dominated issue, both in terms of perpetrators and victims. This gender imbalance is reflected in Braithwaite's facts and other criminological research.

Gender and Theories: The theories discussed in criminology (such as Social Control Theory and Rational Choice Theory) often do not address gender sufficiently, even though proponents of these theories may argue that they are gender-neutral and could be applied equally to both men and women.

Gender vs. Sex

Sex: Refers to biological differences between male and female (e.g., chromosomes, reproductive systems). This is usually seen as a binary concept—either male or female.

Gender: Refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that society attributes to individuals based on their sex. Gender is more complex and includes concepts like masculinity and femininity, which are shaped by cultural and social expectations.

Key Distinction:

Sex = Biological characteristics (male/female).

Gender = Socially ascribed roles and expectations (man/woman).

Heidensohn’s Concept of Control and Gender

Frances Heidensohn (1985): Used the concept of control to explain women’s lives and their relationship to crime. Heidensohn's work contrasts the different ways in which women's lives are controlled in society and how that shapes their involvement in criminal behavior. She identifies three categories:

Under control (by men): Traditional gender roles that control and limit women's behavior in society.

Out of control (being deviant): When women deviate from these roles, they are often labeled as "deviant" or "criminal" (e.g., women breaking away from family structures, engaging in crime).

In control (in powerful positions): As women increasingly enter the workforce and attain power, they gain more control over their lives, but may also engage in crime in ways similar to men (e.g., white-collar crime).

Comparison with Hirschi and Tittle

Hirschi’s Social Control Theory: Focuses on how individuals are prevented from committing crimes through strong bonds with society (attachment, commitment, involvement, belief). However, Hirschi's theory does not specifically address how gender affects these bonds.

Tittle’s Control Balance Theory: This theory suggests that crime occurs when an individual's control is imbalanced—either too much or too little. Like Hirschi's theory, it does not specifically address gender differences in control.

Heidensohn's perspective is more focused on gendered control—how society's control over women differs from that over men and how this affects their likelihood of engaging in crime. Her concept highlights that gender inequality plays a role in shaping crime, whereas Hirschi and Tittle focus more broadly on social control without considering gender as a central factor.

Crimes Heidensohn’s Control Concept Might Make Visible

Crimes of Domestic Violence: Women’s experiences of control in the private sphere (i.e., domestic abuse) may be overlooked in criminological theories that do not consider gender.

White-Collar Crime: As women gain more power in the workforce, they may engage in white-collar crime, challenging the traditional male-dominated notion of corporate crime.

Gendered Crime: Crimes that disproportionately affect women, such as prostitution, female trafficking, and crimes of survival, are better understood through Heidensohn’s theory of control.

Gender-Neutral Theories in Criminology

Criticism of Gender-Neutrality: Many criminological theories claim to be gender-neutral, arguing that they can apply equally to both men and women. For example:

Rational Choice Theory: Focuses on decision-making, assuming individuals (regardless of gender) make rational choices based on costs and benefits.

Social Control Theory: Asserts that crime occurs when social bonds are weakened or absent, without emphasizing how gender affects these bonds.

Critics of Gender-Neutrality: Feminist criminologists argue that criminological theories often fail to account for the specific experiences and structural inequalities that women face. They also point out that crime and criminology are historically male-centric, and thus theories that do not account for gender ignore these significant social dynamics.

The Male-Centric Nature of Crime

Crime as a Male-Dominated Issue: The majority of crimes, both as perpetrators and victims, tend to involve men. This has been a central issue in criminology—how to explain the disproportionate male involvement in crime, and how this male experience is theorized.

Hegemonic Masculinity: A concept used to explain how traditional ideals of masculinity dominate and shape societal expectations for male behavior. It refers to the culturally dominant form of masculinity that emphasizes traits like aggression, dominance, and authority.

Hegemonic Masculinity and Crime: This concept is used to understand why men might commit certain types of crimes, such as violence, because they feel societal pressure to display traditionally "masculine" behaviors.

Gender and the Propensity to Commit Crime

Gender Differences in Crime: There are clear gender disparities in the types and frequency of crimes committed. For example:

Men are more likely to commit violent crimes, particularly street crime, while women are more likely to be involved in non-violent crimes such as shoplifting or fraud.

Socialization: Traditional gender roles socialize men to display aggression and dominance, which could influence their criminal behavior. Women, on the other hand, are often socialized into roles that discourage aggression and criminal activity.

Women as Victims: Crime also affects men and women differently in terms of victimization. Women are more likely to be victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and harassment, crimes that are often underreported and less studied in traditional criminology.

Criminal Justice System: Gender also plays a significant role in how the criminal justice system treats men and women. Women, for example, are often viewed as less dangerous or more rehabilitative than men and may receive different sentences or treatment in the legal system.

The Feminist Perspective

Feminist Criminology: Feminist theorists argue that criminology and victimology have historically been male-centered. Feminists seek to uncover how gender shapes crime, both in terms of who commits it and who is victimized.

Patriarchy and Crime: Feminist criminologists view crime as a product of patriarchal systems that create gender inequality and restrict women's opportunities and autonomy.

Focus on Women's Experiences: Feminist criminologists advocate for understanding crime through the lens of women's experiences, including how gender shapes their opportunities, choices, and victimization.

Conclusion

Importance of Gender in Criminology: Criminology and victimology have historically marginalized gender as a critical variable. Theories that claim to be gender-neutral may fail to account for the unique experiences of men and women in relation to crime.

Need for Gender-Inclusive Theories: There is a need for criminological theories to incorporate gendered perspectives—examining how both men's and women's experiences with crime are shaped by social roles, power dynamics, and structural inequalities.

Hegemonic Masculinity and Crime: Understanding crime through the lens of hegemonic masculinity can help explain why men are more likely to engage in certain types of crime. Meanwhile, feminist criminology emphasizes how gender influences not just crime commission but also victimization and the treatment of offenders.

Criminology must move towards a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of gender, examining both men's and women's roles in crime and victimization while challenging traditional, male-centric perspectives.

Hegemonic masculinity and crime

Definition of Hegemonic Masculinity

Hegemonic Masculinity (Jefferson, 2006): A concept used to describe the dominant set of ideas, values, practices, and representations associated with being male in a given society at a specific historical moment. This dominant masculinity is regarded as the ideal standard of manhood that men strive to achieve and is culturally accepted as the standard for gender relations.

Historical and Social Context: The form of masculinity that is dominant can vary across different historical periods, but it generally emphasizes characteristics such as strength, authority, and heterosexuality, positioning men in a dominant role in society.

Key Contributors to the Theory of Hegemonic Masculinity

Connell (1987, 1995): Australian sociologist who developed the concept of hegemonic masculinity. Connell argues that masculinity is culturally constructed and is deeply tied to the dominant ideology of heterosexuality. This idealized form of masculinity is:

Normatively heterosexual: Men are expected to desire women and see themselves as distinct from women.

Culturally reinforced through various social institutions (e.g., family, work, media).

This type of masculinity is a social construct, not biological, and it maintains its power through societal consent.

Racial and Class Implications: The white, heterosexual male is often positioned as the ideal masculine figure, marginalizing other forms of manhood (e.g., homosexual men, ethnic minority men). This framework also devalues femininity.

Power of Hegemonic Masculinity: This dominant form of masculinity is sustained not just through coercion but also by consent—society, both men and women, accept it as the norm.

Example: Men are expected to perform their masculinity through certain behaviors like being the breadwinner, having sexual dominance, and engaging in physical confrontation, which often correlates with criminal behavior.

Hegemonic Masculinity and Crime

Messerschmidt (1993, 1997): Expanded on Connell's theory by linking hegemonic masculinity to crime in three key social spaces:

The Street: Public demonstrations of masculinity, such as gang violence, street fighting, or aggressive behaviors that reinforce dominance.

The Workplace: Men use their power and authority to maintain dominance in professional settings, often engaging in behaviors like sexual harassment or workplace violence as expressions of their masculinity.

The Home: The domestic sphere is often a site where men assert control and demonstrate their masculinity through violence or coercive behaviors against women and children.

Examples:

Street Crime: Men may engage in violent crimes or gang activities as a way of asserting their masculine identity.

White-Collar Crime: In more professional settings, the executive might exert control and demonstrate power through less overt, but still harmful, actions like sexual harassment.

Domestic Violence: In the home, violence against women and children can be viewed as an expression of male dominance, further cementing patriarchal power structures.

Doing Masculinity: All these forms of crime can be seen as different ways of “doing” masculinity. Men perform their gender role through their behaviors and actions. For instance:

The Pimp on the street and the white-collar executive in the workplace both exert control over women, but through different methods.

Violence—whether physical or sexual—serves as a means to affirm one's masculinity in a patriarchal society.

Masculinity, Victimization, and Crime

Victimization and Masculinity: Men’s struggle with victimization is often linked to the tensions inherent in hegemonic masculinity. Masculine norms often discourage men from showing vulnerability or experiencing victimization, as these experiences challenge traditional views of male strength and dominance.

Masculine Identity and Victimhood: The dominant conception of masculinity often makes it contradictory for men to accept the role of the victim because it undermines their identity as strong and dominant individuals.

Men may feel compelled to reassert their masculinity in response to victimization, sometimes through retaliation or violence.

Criticisms of the Hegemonic Masculinity Framework

Hood-Williams’ Critique (2001): Hood-Williams raises an important question—why do only some men produce their masculinity through crime, while others do so through non-criminal means?

This question points to the limitations of the hegemonic masculinity framework in explaining all forms of crime. While hegemonic masculinity can help explain certain types of crime (e.g., violent street crime, domestic violence), it may not fully account for crimes that do not conform to masculine ideals (e.g., white-collar crime, crimes of passion, etc.).

Criminology's Dilemma: Criminology is often concerned with universal explanations that can be applied across all types of crime. The masculinity thesis, while useful in some contexts, struggles to explain the full range of criminal behavior and may overemphasize the role of gender in certain crimes.

Gendered Perspectives in Criminology

Masculinity and Crime: Understanding hegemonic masculinity provides a valuable framework for analyzing the gendered nature of crime. It challenges traditional views of crime and criminality, emphasizing that:

Crime is not just a behavioral choice but is also shaped by social expectations related to gender.

Criminal behavior can be seen as a way for some men to affirm their masculinity in the face of societal pressures.

Social Power and Crime: The framework of hegemonic masculinity aligns with criminological theories that emphasize how social power dynamics (race, class, gender) affect individuals’ involvement in crime. Men’s engagement in criminal behavior may stem from a need to assert their dominance and control, which is embedded in the cultural ideals of masculinity.

The Role of Hegemonic Masculinity in Crime Prevention

Exploring Alternatives: Understanding the relationship between hegemonic masculinity and crime opens up possibilities for rethinking crime prevention strategies. For instance, addressing the cultural expectations around masculinity might:

Challenge traditional gender roles that encourage violent or aggressive behavior.

Promote positive forms of masculinity, where men are encouraged to express vulnerability, engage in healthy relationships, and avoid criminal behavior.

Future Criminological Agenda: Some criminologists argue that integrating masculinities into criminology’s agenda can offer insights into gendered violence, crime prevention, and the social structures that shape crime. However, the challenge remains to find a balanced perspective that integrates masculinity with other factors influencing crime.

Conclusion

Hegemonic Masculinity and Crime: The theory of hegemonic masculinity provides an important lens through which to view crime. It helps to understand how dominant cultural norms about masculinity influence men's behaviors and criminal actions, from violence on the street to workplace exploitation and domestic abuse.

Limitations of the Framework: While the concept offers valuable insights, it faces criticism for not fully accounting for all types of crime and for potentially oversimplifying the relationship between gender and crime. Criminology continues to struggle with explaining crime in a way that incorporates gender, power dynamics, and other socio-cultural factors.

Value for Criminology: Despite these critiques, hegemonic masculinity remains a useful concept for examining the gendered nature of crime, challenging traditional criminological theories, and pushing for a more comprehensive understanding of how gender impacts crime and criminal justice.

Looking at the evidence: finding a place for state crime?

Introduction to State Crime

State Crime: Refers to criminal activities committed by or on behalf of the state. This type of crime can occur within national borders or in the context of international law and involves actions taken by the government, state officials, or state institutions, often for political, economic, or social control.

The study of state crime challenges criminologists to consider the scope of criminal behavior beyond individual or corporate actions, addressing crimes committed by powerful state institutions.

Key Insights from Rothe and Friedrichs (2015)

Intra-State Crime: Much of criminology has focused on "intra-state" crime—criminal behaviors that occur within national boundaries. These crimes are often committed by individuals and organizations, with a focus on visible and identifiable offenses.

State Crime: Rothe and Friedrichs argue that criminology has largely overlooked the role of the state in committing crimes, whether within its borders or abroad. Their work highlights how states engage in activities that break the law but are often not viewed through the lens of criminality.

Types of State Crime

Waging War:

The legality of war is often questioned, particularly with regard to wars of aggression or conflicts that violate international law.

Example: The 2003 Iraq War and the ongoing war in Afghanistan raised debates about the legality of military intervention, the justification for war, and the ethical considerations of state-sponsored violence.

Genocide:

State-sponsored genocide involves the mass killing or persecution of a specific ethnic, racial, or political group.

Example: The genocide in Darfur (Sudan) is a prime example of a state-led crime, where the government targeted specific groups within its borders, violating international human rights law.

Exploitation of Resources:

Corporate and state exploitation of resources in the Global South, such as mining or access to water rights, often occurs under questionable or illegal circumstances.

States in the Global North often play a role in facilitating this exploitation through policies, economic support, or direct intervention in foreign states.

Example: The extraction of natural resources and minerals in countries in Africa or Latin America by multinational corporations backed by Western states.

Human Rights Violations:

States may engage in activities that violate both domestic and international human rights laws, such as torture, displacement of populations, or surveillance and control of populations.

Braithwaite’s Facts and State Crime

Braithwaite’s Facts: Braithwaite (1989) outlined 13 facts any theory of crime should be able to account for. These facts relate to various aspects of crime, including:

Nature of criminal behavior (who commits crime, under what conditions, and why).

Social dynamics surrounding crime (how crime is perceived, its impact on society, and the mechanisms for control).

Application to State Crime:

Some of Braithwaite’s facts may be applicable to state crime, especially in the context of corporate crime, where state involvement can facilitate criminal actions by powerful entities.

However, state crimes like war, genocide, and exploitation may not be fully explained by Braithwaite’s facts, which focus more on individual and corporate crimes within national borders.

Visibility of State Crime in Criminology

State Crime as Invisible:

State crime is often invisible or underreported in mainstream criminological discourse. This is partly because states hold the power to define legality, making their actions less likely to be framed as criminal.

Many actions taken by states (such as military interventions, economic exploitation, and human rights abuses) may be justified as national security, economic interests, or political necessity, which can obscure their criminal nature.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding State Crime:

Rothe and Friedrichs’ Overview: These criminologists explore several theoretical frameworks to understand state crime, including:

Critical Criminology: Focuses on how power structures, such as the state, create and enforce laws that protect their own interests while criminalizing the powerless.

Social Control Theory: In the context of state crime, this theory can be used to examine how states maintain control through both formal institutions (e.g., police, military) and informal means (e.g., propaganda, surveillance).

Green Criminology: Analyzes environmental crimes, including those committed by the state in the form of resource extraction or environmental degradation.

Conflict Theory: States are viewed as entities that serve the interests of the powerful (e.g., corporations, elites), and this power dynamic contributes to state-sponsored criminal behavior.

State Crime and Globalization:

In the context of globalization, state crime has become transnational, with states engaging in criminal activities that affect other nations, often in the form of military interventions, economic exploitation, or the spread of illegal goods (e.g., arms trafficking).

Example: The involvement of the U.S. in supporting or directly conducting military operations in foreign countries, the pursuit of economic policies that disproportionately harm global south countries, or the imposition of unfair trade agreements.

Theoretical Application to State Crime

Does Current Criminology Address State Crime?

Current criminological theories largely focus on individuals and corporations as the primary agents of crime, often overlooking the state as a significant actor in criminal behavior.

There is a need for criminology to expand its theoretical framework to better incorporate the role of the state in committing crime, especially in the context of international law.

The Role of Power in State Crime:

Understanding state crime requires recognizing how power dynamics shape both the definition and response to criminal behavior. The state often has the power to create laws that shield itself from being criminally prosecuted, even when its actions may violate human rights or international norms.

Criminologists must address the way state actions, such as war, genocide, and resource exploitation, are either justified or hidden under national interest or sovereignty arguments.

Conclusion

State Crime in Criminology: While much criminological theory has focused on intra-state crime, state crime—particularly crimes committed by or on behalf of the state—is an important area for further criminological exploration.

Braithwaite’s facts may not fully account for state crime, particularly crimes like war or genocide, which are often obscured by political narratives.

Rothe and Friedrichs provide valuable insights into understanding the theoretical underpinnings of state crime and highlight the need for criminologists to consider state actions in their analysis of criminal behavior.

A word on cultural criminology

Introduction to Cultural Criminology

Cultural Criminology is a criminological perspective that examines crime not just through traditional law-breaking frameworks but also through the lens of culture, media, and societal influences.

Jeff Ferrell (2006) defines cultural criminology as the study of how crime is represented by various media sources and how those representations convey meaning and values to those involved in crime and crime control.

Key Focus: It aims to understand how culture, crime, and crime control intersect and influence each other. This includes the role of media, expressive forms like art and film, and how these cultural products affect societal understanding and the experience of crime.

Key Aspects of Cultural Criminology

Crime as Thrill and Pleasure:

Crime is not always about rational, instrumental motives, but is often driven by thrill-seeking, pleasure, and risk-taking.

It explores the emotional and psychological experiences associated with crime, such as adrenaline, excitement, rage, and humiliation.

Jock Young (2004) emphasizes that crime can be viewed as “edgework”—a dangerous but pleasurable experience where individuals feel alive by engaging in risky behavior.

The Role of the Media:

Media Representation: Cultural criminologists argue that the media plays a central role in constructing and reconstructing the crime problem. The media (TV, film, internet, etc.) shape public perceptions of crime and influence both personal experience and collective consciousness.

Instantaneous Reporting: The rapid, real-time reporting of events (such as wars, terrorist attacks, and criminal trials) through television, social media, and other platforms blurs the line between actual experience and mediated experience. People often rely on mediated experiences to understand the world, making the distinction between what is real and what is represented increasingly unclear.

Virtual Communities and Crime:

The rise of online communities and virtual spaces has created new avenues for crime, such as cybercrime and online exploitation. For instance, in virtual spaces like chat rooms, crimes like paedophilia can occur without the need for direct interaction in the physical world.

Cultural Criminology studies how online spaces contribute to the normalization and reinforcement of certain types of criminal behavior.

Criminal Experience as Creative Expression:

Crime as a Response to Bureaucracy: In a highly bureaucratized and rule-bound society, breaking the rules and engaging in deviant behavior can be seen as a form of creative expression, a way of asserting individual autonomy and challenging societal norms.

Crime is viewed as a way for individuals to express discontent with the system and feel alive by engaging in activities that challenge social order.

Immersion in Criminal Subcultures:

Cultural criminologists argue that to understand crime, researchers must become immersed in the subcultures they study and engage in ethnographic methods to reflect on the lived experiences of those involved in crime.

This approach contrasts with traditional criminology, which often relies on quantitative methods to measure crime.

Anti-Positivism:

Cultural criminology rejects the idea that criminology can be a purely objective science in the positivist sense. It challenges the clear-cut distinction between criminal and normal behavior.

It focuses on the subjective experiences of individuals involved in crime and recognizes that crime and deviance cannot always be universally defined.

The Motivation for Crime in Cultural Criminology

Cultural criminologists emphasize that the motivation for crime often arises from factors like adrenaline and the desire for sensation, rather than rational decision-making.

Risk-taking and seeking pleasure become key drivers of criminal behavior. It is not just about material gain or survival, but about the experience itself.

Theoretical Contributions and Key Figures

Jeff Ferrell (2006):

Focuses on the role of media in crime representation and emphasizes how media representations of crime influence societal perceptions of criminality and moral values.

Jock Young (2004):

Describes cultural criminology as capturing the phenomenology of crime, which includes the emotions and experiences tied to crime, such as pleasure, desperation, rage, and panic.

Focuses on how postmodern society shapes individuals' interactions with crime and emphasizes difference and diversity in criminal behavior.

Winlow and Hall (2006):

In their study of young people, they explored how they experience their lives in a consumerist society, where egoism and competition are central.

They observed that these youths engage in violence as part of their socialization, especially on "good nights out". The boundary between being a victim and a perpetrator of violence becomes blurred.

This study highlights how violence becomes normalized in certain social settings and how young people develop a complex understanding of violence as both active participation and witnessing.

Challenges Posed by Cultural Criminology

Challenging Traditional Criminology:

Cultural criminology presents an alternative view that challenges the traditional criminological focus on objective measures of crime and deviance.

It rejects the idea of universal definitions of crime and argues that crime cannot always be objectively measured or universally understood. The subjectivity of crime and its meanings must be considered.

The Role of Difference and Diversity:

Cultural criminology highlights how individuals in contemporary society navigate and make sense of crime in their own way, often based on personal experiences and cultural contexts.

The emphasis on difference and diversity suggests that crime and criminal behavior need to be contextualized within individuals' everyday lives and experiences.

This perspective provides a deeper understanding of how people construct their sense of morality and criminality in a postmodern world.

Crime as a Social Construct:

Cultural criminologists argue that crime is not only an objective reality but is also a social construct, shaped by culture, media, and societal values.

The role of popular culture (e.g., films, music, TV shows) in shaping perceptions of crime, as well as how individuals internalize these representations, is a crucial area of interest in cultural criminology.

Applications of Cultural Criminology

Cultural criminology can be applied to study various forms of criminal behavior, such as violent crime, cybercrime, drug use, police brutality, and war crimes.

Case Studies:

Violence in Youth Culture: The normalization of violence in certain youth subcultures, as seen in Winlow and Hall's study of young men.

War and Murder: Examining how the experience of war or school shootings is shaped by cultural narratives of violence, power, and masculinity.

Police and Ethnic Minority Relations: How media representations of police and criminal behavior influence public perceptions of racialized crime and police misconduct.

Conclusion

Cultural criminology challenges the traditional criminological frameworks by focusing on the cultural, emotional, and subjective aspects of crime.

It emphasizes how media, expressive practices, and cultural contexts shape crime and its representations in society.

By examining crime from a cultural perspective, criminologists can gain a deeper understanding of how individuals experience crime, why they engage in criminal behavior, and how society interprets and responds to criminal acts.