W11: Technology and progress: from industrialisation to AI

The role of economic growth itself on the underpinning of these changes in economic thinking. We look at the patterns of growth within the world economy but also look at what does economic growth mean? And the criticism of our concept of economic growth itself.

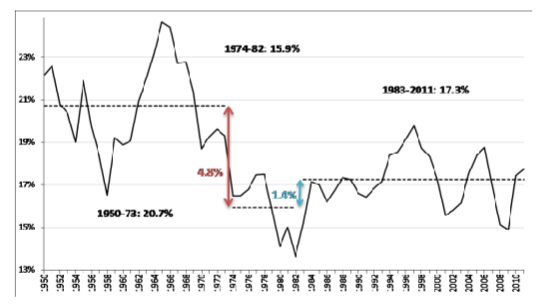

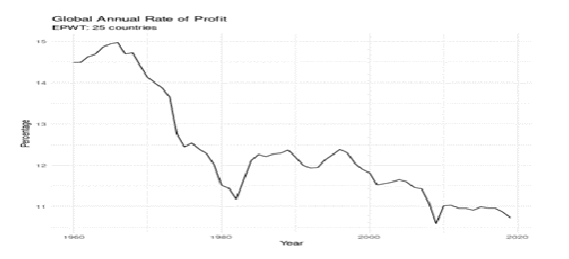

Rate of Profit in Manufacturing Capital 1950-2010

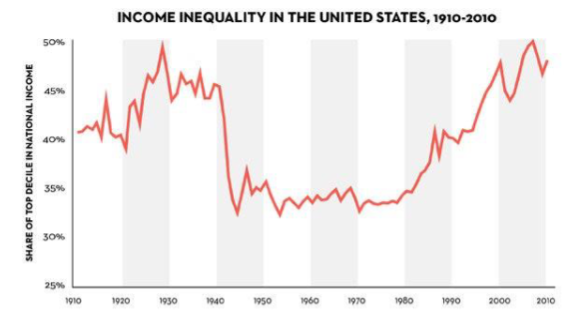

The implications of these changing profit rates within the global economy has been identified with a sharp rise in inequalities by authors such as Thomas Piketty and Blanko Milanovic.

Piketty makes the case for a large return of income inequality in the advanced economies since the 1970s, leading to what he refers to as a Patrimonial capitalism. His explanation arises from a recognition that those that hold wealth and those that rely upon their income from labour markets have seen differential levels of growth since the 1970s.

Returns to asset holding (R) have grown faster than GDP from which labour income is derived (G).

R>G over time has concentrated wealth in the hands of smaller numbers of the world’s population - 0.1% of the population in advanced economies.

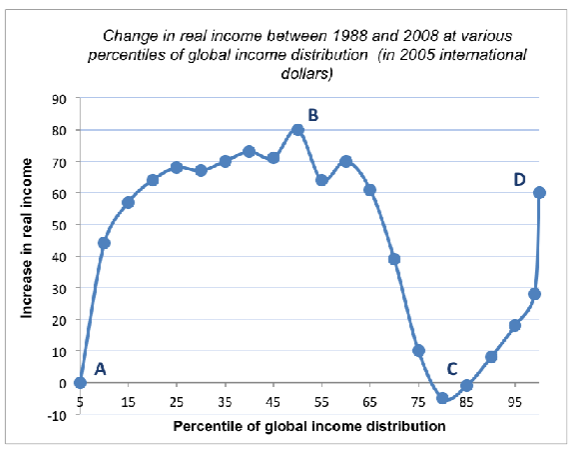

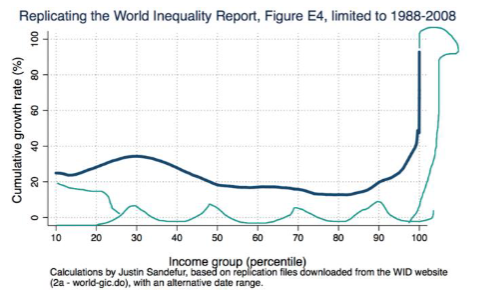

Christoph Lakner, C. and Milanovic, B. (2015), ‘Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin wall to the great recession’, The world bank economic review, August 12, 2015

Their argument is that gobally inequality has altered the balance of income growth. The bottom 10% of the global population has missed out on world economic growth whilst a large newly developed world working class has emerged in which their income growth has been rapid as a result of urbanisation, industrialisation and accounts for the bottom 10 to 60% of the global population. From the 60% percentile to the90th percentile has seen rapidly falling income growth such that deindustrialisation, the growth of low wage service employment and debt have all combined to create falling living standards. Finally the top 1% have seen the most rapid increase in income as inequality rose rapidly. A curve looking like an ‘elephant’ can be identified.

Another view of this comes from the World Inequality Report 2018 of a snake.

Whether there is an elephant, a snake or other animal the rapid rise of wealth holding elites is common to these pictures. In other words the growth in the world economy has not been equally shared.

Supporters of free markets would say this is to be expected and over time these advantages will be dissipated away as the Marginal Product of Labour converges to Marginal Product Revenue.

In equilibrium MPL=MPR

A further challenge to these questions is what is economic growth? For a long period it has been recognised that much of what we refer to as growth (GDP) is a measure of market transactions. But there is much of our economic activity which is not subject to market exchange.

Households are not run based upon exchange between individuals within it.

Pollution is not seen as a cost of production but an opportunity for further profit and growth through paying for the costs of clearing pollution up. But surely decommissioning a nuclear power station is actually part of the original cost of production? But instead it is now a second opportunity to generate further income.

Goods can also be produced with limited life, from light bulbs to white goods in households. Much of advertising is aimed at influencing decision making but not better decision making. There is a distinction to be made between a use value and an exchange value.

Lots of work is voluntary in communities is given without the exchange of money.

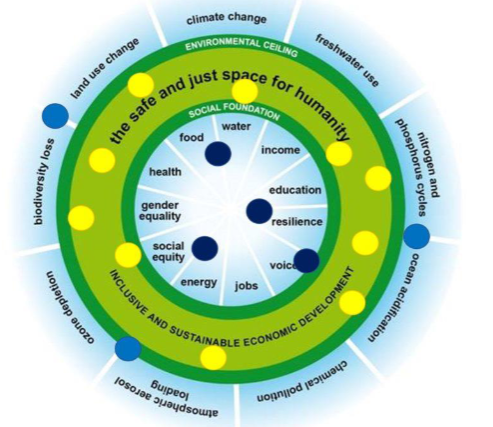

Kate Raworth Doughnut Economics

Raworth seeks to develop a notion of development which doesn’t emphasise economic growth measured as market exchange but a wider notion of sustainability and well-being.

A further example of the attempt to broaden out our understanding of economic development comes from the UN Human Development Index, begun in 1990.

This seeks to combine measures of economic activity (through standards of living), with wider societal measures of impact (healthy life indicators) and human capital (educational index) to achieve a broader measure of well-being.

Climate Change private markets or Public Goods

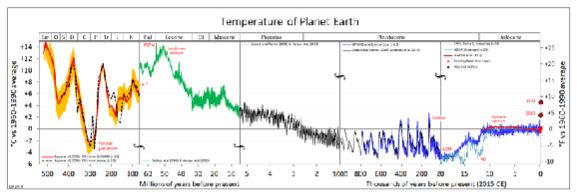

Metabolic drift

The speed of which the natural environment has emerged and changed relative to the rate of change in the environment under industrial capitalism.

role of two ecological systems in metabolic drift, two component part of greenhouse gases: the carbon cycle and nitrogen cycle.

Alternative approaches to climate solutions

Private markets

Innovation within existing conceptualisation of economic development. Innovation and technological change. Using Payment for Environmental Services and underpinned by economic concepts of Private Property rights versus communal rights and Privatised Markets versus socialisation of environment.

Alternatives to market co-ordination: public goods

Private markets fail to recognise the role of externalities. That is costs of production can be minimised by externalising additional costs. Thus, replacing rain forests with mono culture tree planting of trees for palm oil or trees used in the building industry may capture carbon in forestry but destroys biodiversity.

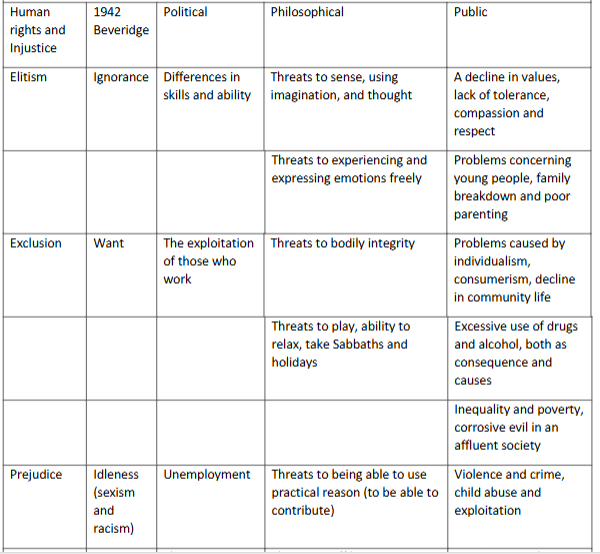

Health and Social Inequalities

The Rationale for Social Policy

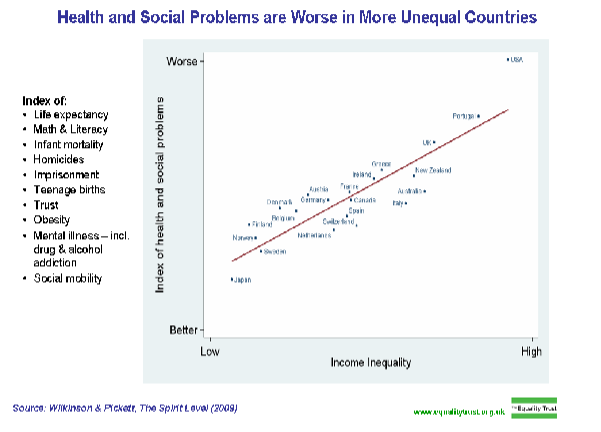

Previous lectures have shown how imperfectly competitive markets can give rise to outcomes which adversely affect citizens. Inequality becomes a structural feature of society. We can consider inequality in terms of inequality of opportunity and also inequality of outcomes.

These structural inequalities may have geographic effects, intergenerational effects or effects for specific groups’ characteristics, gender, race, disability, sexuality, etc.

northern regions within the UK face disadvantages compared to that the south-east has (e.g. government departments have their headquarters there), and social and other policies can be useful in these circumstances.

groups with ‘poor standard’ at work (e.g. young workers) replace jobs from groups with ‘higher standards’ at work (e.g. older workers)

One reason why we can argue for a role for Social Policy is that some of the developments that have to be addressed result from government action in other fields; in particular, neo-liberalism:

greater competitive pressures on firms results in knock-on effects (e.g. lower wages) for their workers

greater labour mobility may result in the need for ‘protection’ for migrant workers, and there could be implications for workers who do not migrate.

greater choice for firms with regard to the location of factories - firms can seek out those areas with the least social protection - this could lead to ‘social dumping’

There are many other examples of inequality, and the effects that they have on people’s lives:

inequality is inflicted upon multiple generations

a child’s success at school is strongly linked to the educational achievement/social class of their parents

going to university is much easier if parents can financially support their children

many universities still take in a disproportionate number of ‘public’ school students

access to services (or the cost of them) can be related to (non-universal) pre-pay meters for electricity

access to services can be related to (non-universal) provisions - rural versus urban access to transport

government services are increasingly being provided online

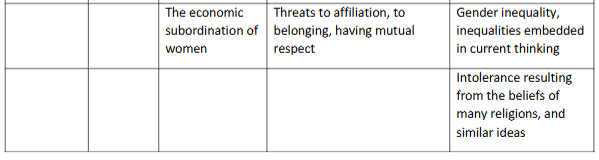

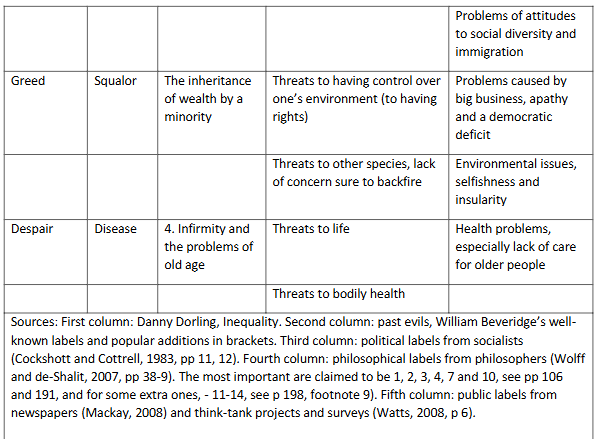

Inequality may be structural rather than personal decision making class structure:

Approaches to Social Policy

Wilkinson and Pickett: the Spirit Level

Health Expenditure

UK total public health expenditure is approximately 80.9%. In contrast other OECD countries have wider variation. Although private health insurance accounts, on average, for 6.3% of total expenditure on health (THE), its importance in funding OECD health systems varies significantly. The US is the only OECD country where voluntary health insurance represents the main health financing and coverage system for most of the population, explaining why private health insurance accounted for 35% of THE in 2000. In France, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada, the share of financing accounted for by private health insurance ranges from 10% to 15% of THE. A similar level is found in Switzerland, where 10% of total health expenditure comes from the voluntary supplementary health insurance market. Australia, Ireland, Spain, New Zealand, and Austria have levels of PHI financing between 4% and 10%. Private health insurance in all other OECD countries contributes much less than 4% to funding total health expenditures.

Other aspects of health inequality

Possibly the most concerning inequality is that of life expectancy. The data below two consistent patterns in the life expectancy literature - women live longer than men and that people in richer countries tend to live longer than people in poorer countries.

The Importance of Pluralist and Heterodox ideas

Ways in which crisis and dynamic change can enter the curricula

Theories of the firm:

Residual Claiment and property rights

Hayek (1944); North (1981)

Internationalisation and behavioural

Coase (1937); Chandler (1994)

Surplus value and labour process

Marglin (1973); Pitelis (1993)

Government and Competition

institutional failure

Eichengreen (1996); Broadberry and Crafts (1996, 2001)

UK relative economic decline

Booth (2003), Tomlinson (1996, 2009), Edgerton (2006)

Origins of growth

Sclerotic tendencies

Olson (1965, 1982)

Entrepreneurship and innovation

Schumpeter (1943); Casson (1998)

Entrepreneurial State

Mazzucato (2013)

Boundaries of the firm

Managerial limits to growth

Penrose (1958)

Visible hand and transaction cost economics

Chandler (1990); Williamson (2002)

Nexus of contracts

Aoki (1990)

Monopoly capital and imperialism

Braverman (1978); Callinicos (2014)

Origins of crisis and dynamic change

Marxism and the tendency of the rate to profit to decline

Use and exchange values

Marx (1970); Harman (2009); Harvey (2006)