Wickard v Filburn Case Assignment Review

Wickard v. Filburn

Name of Case: Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111, 63 S.Ct. 82, 87 L.Ed. 122 (1942).

Plaintiff: (Roscoe) Filburn

Defendant: Secretary of Agriculture Claude Wickard (for the United States)

Court: The Supreme Court of the United States

Opinion: Justice Robert H. Jackson

Statement of Facts

6. Facts of Case (Substitute one or two sentences for each parenthetical item in order)

6.1: (Congressional Statute and Purpose)

6.2: (Statute’s directive to Agency and Agency’s programmatic implementation same)

6.3: (Plaintiff’s basic situation and act of alleged violation)

6.4: (Agency’s response to Plaintiff’s alleged violation)

6.5: (How did Agency’s response injure Plaintiff?)

Timeline

Statement of Facts

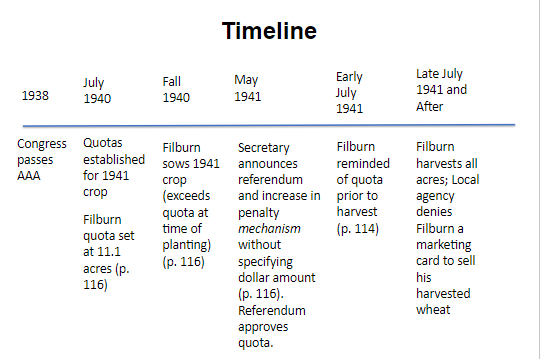

6.1. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 (7 U.S.C. § 1281 et seq.) was enacted to set strict limits on farm production to control market excess in order to support higher market prices. The Act tied

6.2. [The Act] directed the Department of Agriculture to allocate quotas to farmers and establish per-bushel penalties for any excess production, as well as methods for enforcing such penalties. he Act required the Secretary of Agriculture to hold a referendum of affected farmers concerning the quota.

6.3. In July 1940, Plaintiff Filburn’s quota was set at 11.1 acres by the local county agriculture board. That fall he planted 23 acres of wheat, 11.9 acres in excess of his quota. On May 19, 1941, Agriculture Secretary Claude Wickard by radio address increased the per bushel penalty from 15 cents to 49 cents. The effective date of the increase was May 26, 1941.

6.4. Upon harvest, the county agriculture board levied a fine of $117.11 for Filburn’s excess wheat harvest of 239 bushels. Per the Act, Filburn had the option to pay the fine and sell his crop, deliver the excess wheat to the Secretary of Agriculture, or store it for the next year through specific instructions given via the Secretary of Agriculture.

6.5. Upon failure to pay the fine or avail himself of the alternatives to avoid it, the county agriculture board placed a lien on Filburn’s entire crop, as well as denying him a marketing card required to legally sell his wheat.

7. Procedural Posture

7.1 Mr. Filburn filed suit in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Ohio to enjoin the County Agriculture Board’s enforcement of the quota excess penalty, arguing that a) that the excess wheat production was intended for on farm-use and not for interstate sale and thus beyond power of federal regulation under the Commerce Clause, and b) that the penalty increased after he planted his wheat crop and therefore violated his Fifth Amendment right to due process. In a two-to-one opinion in District Court, the three judge panel permanently enjoined the USDA from collecting the penalty in excess of the fifteen cent penalty in place at time of planting. The panel majority rested its decision on the failure of the Secretary to mention the penalty increase in advance of the referendum. (see Filburn v. Helke, 43 F. Supp. 1017 [S.D. Ohio, 1942]).

7.2 The Secretary of Agriculture appealed the District Court’s ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court.

8. The Issues (Branan’s take)

8.1 Whether the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, in granting the Secretary of Agriculture the power to regulate all wheat production is an unconstitutional extension of Congressional power as limited by the Commerce Clause (which limits Congressional power to regulation of commerce between the states).

8.2 Whether the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, as amended on May 26, 1941, violated the appellee’s U.S. Constitution Fifth Amendment guarantee of due process by increasing the per excess-bushel penalty for a crop already planted.

Holdings and Disposition

The Court held that the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 was proper exercise of the United States government’s power under the Commerce Clause to regulate the intrastate use of a crop that has a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce, and

that the Act was not a violation of Filburn’s Fifth Am. Due Process rights as Filburn had prior notice of the existence of a per excess-acre penalty as well as alternatives to avoid the excess penalty.

Disposition: Reversed

Commerce Clause Key Quote

“The effect of the statute before us is to restrict the amount which may be produced for market and the extent as well to which one may forestall resort to the market by producing to meet his own needs. That appellee's own contribution to the demand for wheat may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his contribution, taken together with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.”

- Wickard v. Filburn**, 317 U.S. 111, 128 (1942)**

Due Process: Congress Defined “Marketing”

The Court states that “[m]arketing of wheat was defined [by the Act] as including disposition 'by feeding (in any form) to poultry or livestock which, or the products of which, are sold, bartered, or exchanged.” (Id. at 120 )

This is the linchpin that addresses the due process claim, in that the Court, in following emerging precedent on the deepening reach of Congress under the Commerce Clause (e.g. Darby), held that Filburn did exactly what Congress defined as “also marketing” (quotations added).

Had Congress not provided the marketing definition to include feed for livestock, the Court may have upheld the Due Process claim.

The Essence of Regulation – Role of Court and Congress

p. 129: “It is of the essence of regulation that it lays a restraining hand on the self-interest of the regulated and that advantages from the regulation commonly fall to others. The conflicts of economic interest between the regulated and those who advantage by it are wisely left under our system to resolution by the Congress under its more flexible and responsible legislative process. Such conflicts rarely lend themselves to judicial determination.”

And more…

Converting regulated excess to unregulated goods. The comment on Wickard v. Filburn notes that the idea of feeding regulated grain to livestock is simply a conversion of the commodity from grain to milk, meat or eggs.

Harvesting was crucial. It appears Filburn planted 23 acres of wheat before the May 26 Amendment became effective. His quota was set before the Amendment even if the increase in penalty was set after. The Act was clear that the penalty is assessed (becomes due and payable) at the time of threshing (separating the head from the stalk). Once threshed the wheat becomes part of the national market aggregate. When Filburn learned of the increased penalty, he still threshed the wheat instead of feeding it as hay.

Cake and eat it too

The Court several times emphasized that Roscoe Filburn was on the one hand marketing his wheat at a price higher than the world market due to the Act’s production/price control scheme, while maintaining that it was unjust (lack of due process) that he should follow the rules of the production/price control scheme. As the Court said, “It is hardly lack of due process for the Government to regulate that which it subsidizes.” (Filburn p. 131)

Epilogue

Justice Jackson

Dissented in Korematsu v. United States, 1945

Chief Prosecutor at Nurenburg Trials, 1946

Died shortly after joining the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision, 1954

Roscoe Filburn

Changed his name to Filbrun, last of his family to farm

He and family sold the farm in 1966, now the Salem Mall in Dayton, OH

Died in 1987

Claude Wickard

Banned sliced bread during World War II

Ran the Rural Electrification Administration after the War

Killed in a car wreck, 1967

Wickard v. Filburn High Water Mark

United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995) (invalidating the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990). Chief Justice William Renquist wrote that gun possession is not an economic enterprise, noting that the Act did not grant the courts jurisdiction to determine an economic connection on a case-by-case basis.

United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000) (invalidating the Violence Against Women Act). Renquist wrote that "[g]ender-motivated crimes of violence are not, in any sense of the phrase, economic activity." (Morrison at 613) Also, Renquist wrote that VAWA lacked a statutory grant of jurisdiction linked to economic activity.

Cannabis - Gonzales v. Raich**, 545 U.S. 1 (2005)**

A 6-3 opinion by Justice Stevens (Scalia concurring separately) (Renquist, O’Connor [dissenting] and Thomas voting against)

“The similarities between this case and Wickard are striking. Like the farmer in Wickard, respondents are cultivating, for home consumption, a fungible commodity for which there is an established, albeit illegal, interstate market.... In Wickard, we had no difficulty concluding that Congress had a rational basis for believing that, when viewed in the aggregate, leaving home-consumed wheat outside the regulatory scheme would have a substantial influence on price and market conditions. Here too, Congress had a rational basis for concluding that leaving home-consumed marijuana outside federal control would similarly affect price and market conditions.”

Knowt

Knowt