Economic Way of Thinking - 4. Cost and choice, the concept of supply

- The theory of supply is not essentially different from the theory of demand.

- They're both based on opportunity costs.

Costs are tied to actions, not things

- A "thing" cannot have a cost, only actions have costs.

- It is for this reason that the economic way of thinking recognizes no objective costs.

- Since purchasing is an action, it can entail sacrificed opportunities and thereby have a cost.

- The cost of manufacturing and selling have different costs.

- All costs are costs to someone who places value on forgone opportunities.

- What I got someone else can't have.

The irrelevance of "sunk costs"

- The value of something to people is what they would be willing to pay for an additional amount in the actual situation in which they find themselves.

- Most people go astray by confusing the total value of a good (or costs previously incurred) with its marginal value.

- The proper stance is looking forward to current opportunities, looking at the future.

- Sunk costs are what you pay for something that didn't end up being worth the cost.

- They are irrelevant to economic decisions, as bygones are bygones.

- The only costs that matter are marginal costs, and these always lie in the future.

- But we must be certain that a cost is really sunk before it is regarded as irrelevant.

- "A student that dropped a course already spent $100 on a book. If he sells it for $20, his sunk cost is $80. He can't get back the value of the book by reading all of it."

Producers' costs as opportunity costs

- When we think about producers' costs, we tend to think first of what goes into the production of each.

- This isn't wrong, but it opens two questions: why did they choose to produce that specific product? What did it cost to use these inputs?

- There are substitutes for everything in production as well as in consumption.

- This asserts that the amount of money a producer must pay for any resource will depend on what the owner of that resource can obtain from someone else.

- Because these resources have other opportunities for employment, the manufacturers must pay a price that matches the best opportunity value.

- All opportunity costs are marginal costs, and all marginal costs are opportunity costs.

- They are the same thing viewed from different angles.

- Opportunity costs are opportunities forgone by actions, while marginal costs are changes in the existing situation that the action entails.

- The full name is marginal opportunity cost for any cost that is relevant in decision-making.

- Mantra on costs: ==only actions have costs, all costs are costs to someone, all costs lie in the future==.

Costs and supply

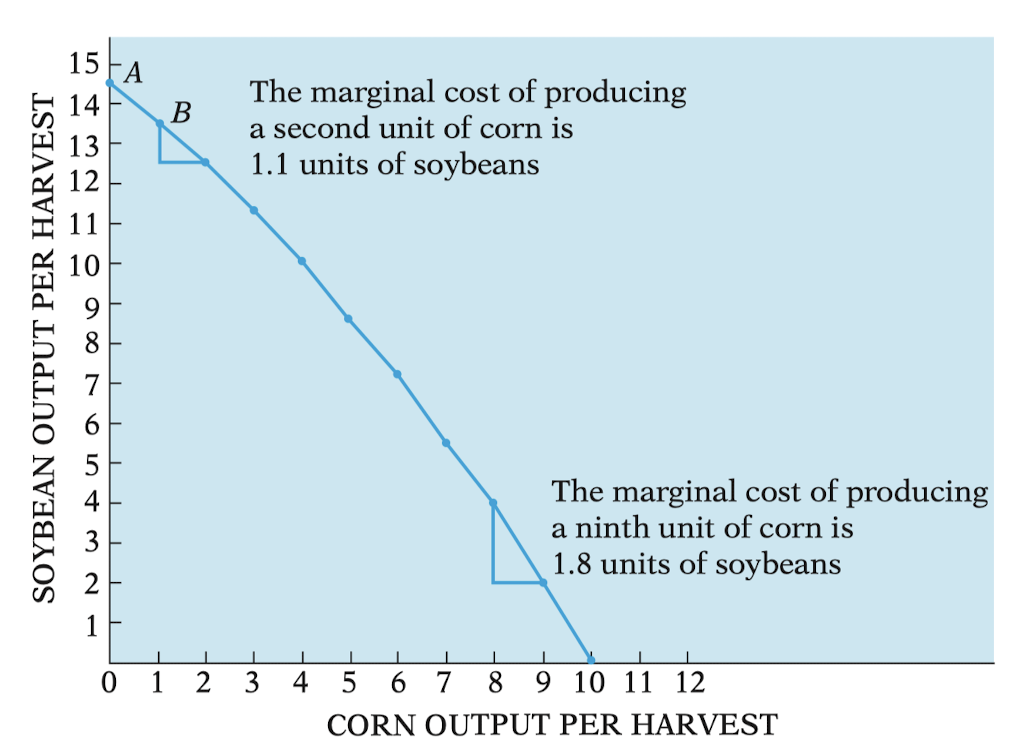

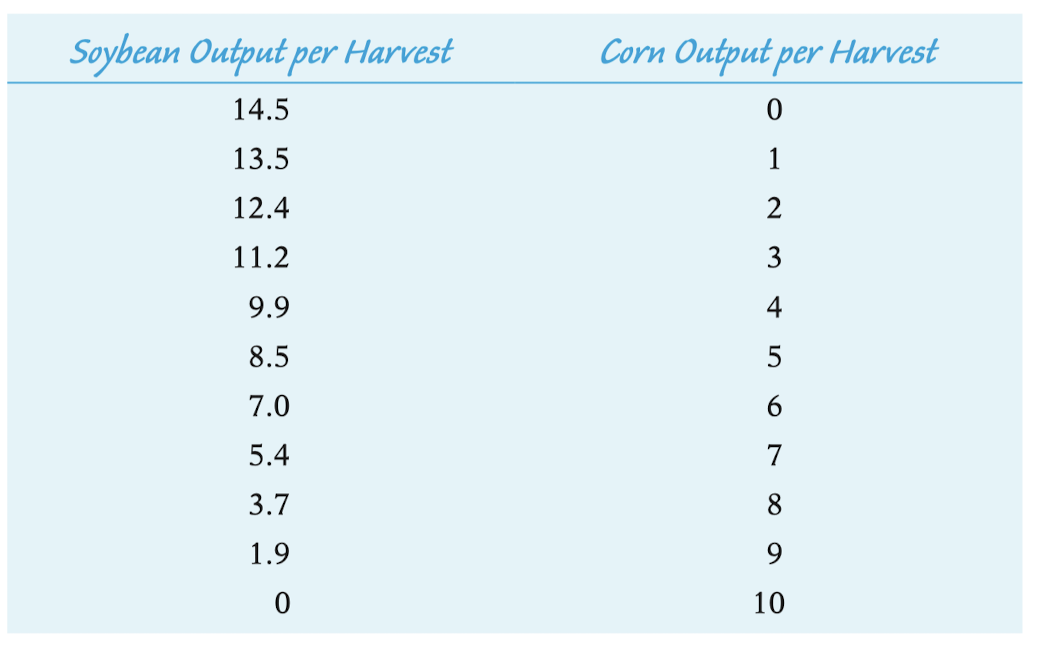

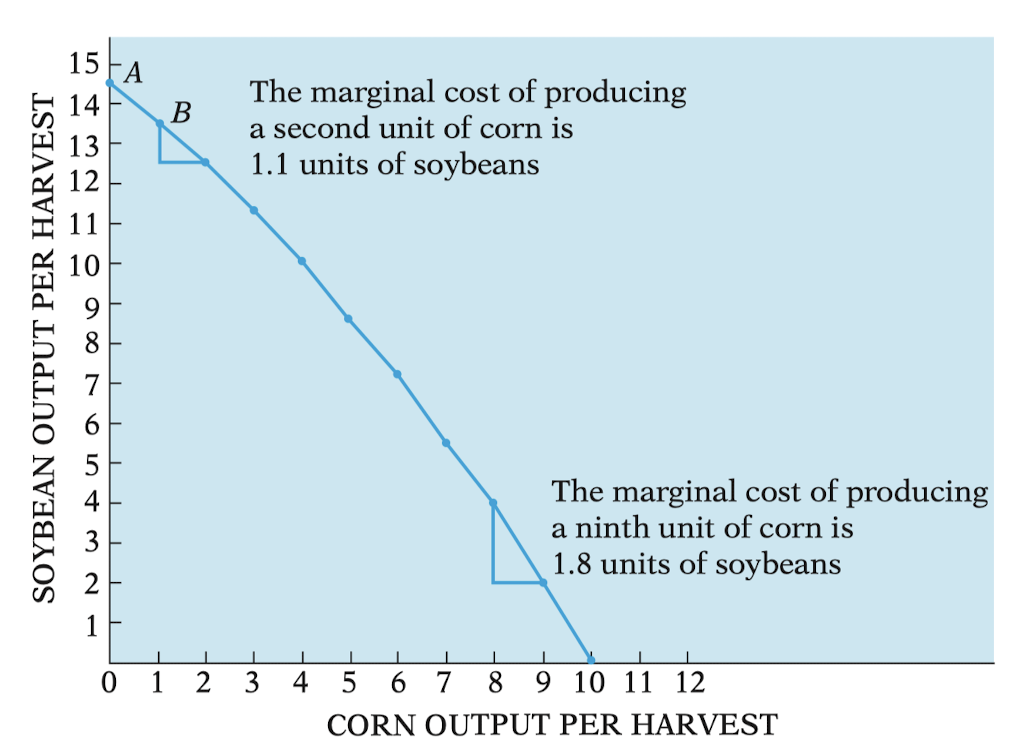

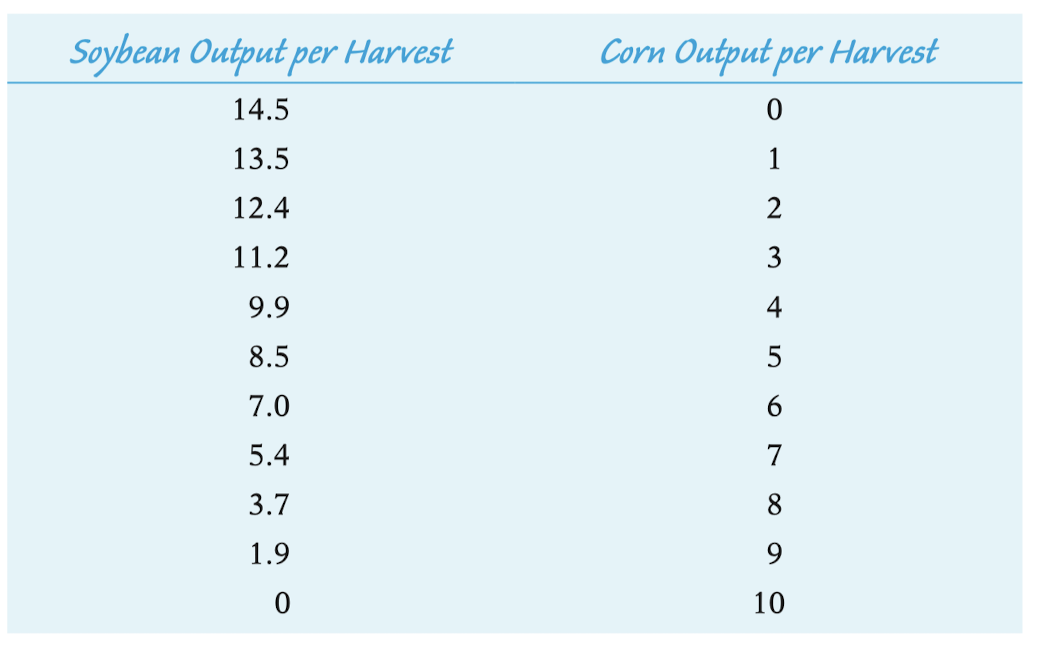

- This subtitle talks about the PPF for the costs and benefits of producing one product versus the other.

- Depending on the price that each product sells for, the farmer will choose to produce more or less of a product.

- Producers consider marginal costs of production when deciding upon which outputs to produce.

- Relative prices inform producers of the marginal costs, and marginal benefits, of their alternative production plans.

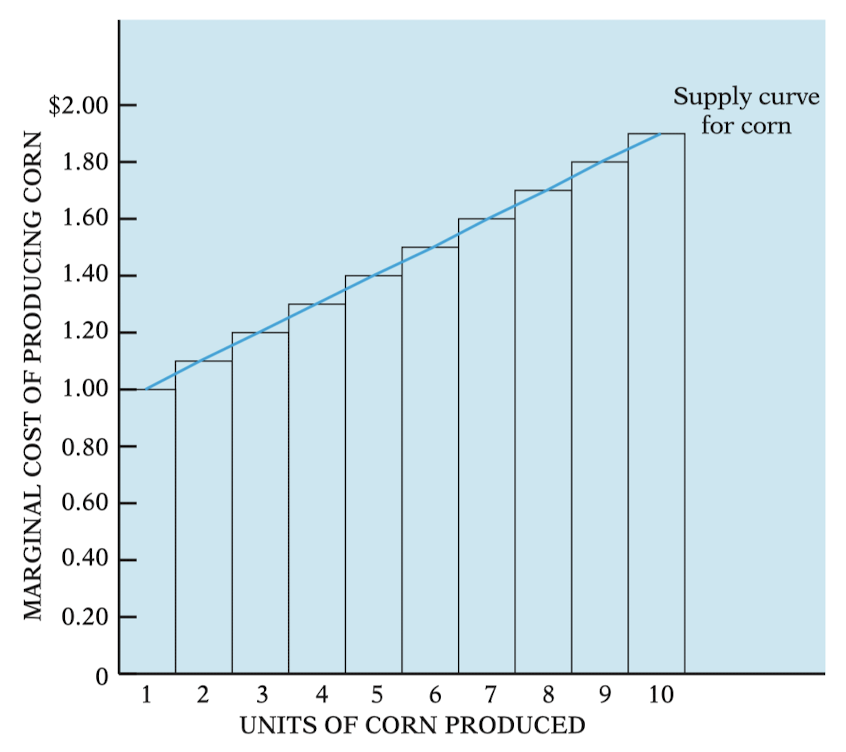

The supply curve

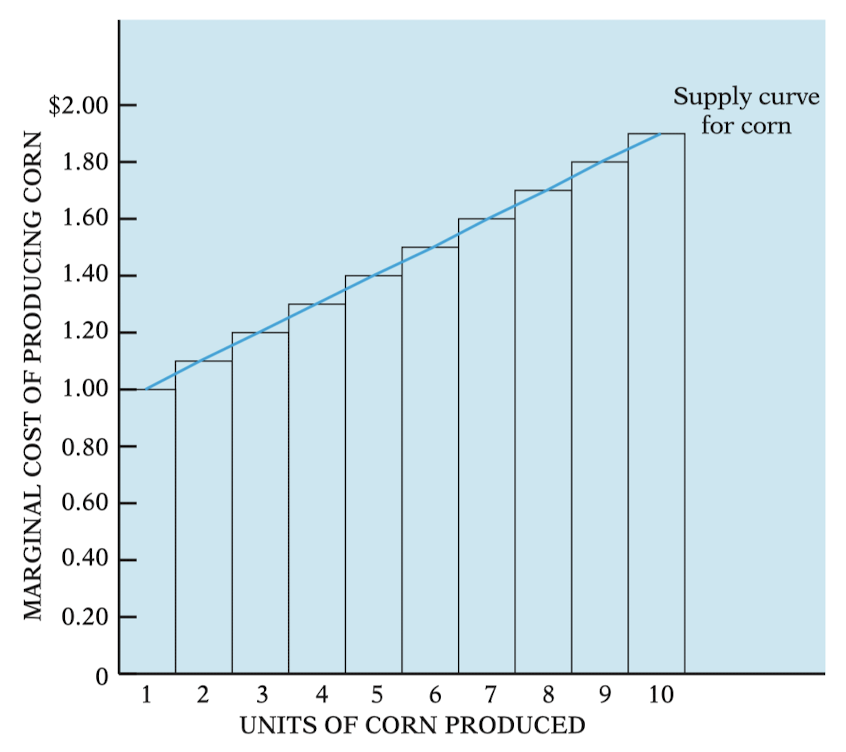

- The upward-sloping line illustrates the supply curve.

- Each bar represents the marginal cost of producing.

- The total area underneath the supply curve represents the total costs of production

- Supply curves are the marginal opportunity cost.

- Changes in the supply curve can be:

- A rise or fall in the price of a factor of production.

- Technological changes increase overall supply.

- Resource deterioration decrease overall supply.

- A change in the relative price of an alternative product.

- A change in the expected price of the producer's output.

- A change in the overall number of suppliers.

- The entry of more competitors would increase overall supply.

- Expected profits will encourage entry.

- Taxes and subsidies

- Taxes lower supply, subsidies increase supply.

Marginal and average costs

- It's important not to get the marginal concept mixed up with the notion of average.

- Marginal costs drive choices, average costs don't.

- Marginal costs are consequences of an action. The anticipated cost of any decision are really marginal costs.

- Averages can be looked at afterwards to see how well or poorly things went.

- Economic decisions are always made in the present with an eye to the future.

- Decisions are often made in a "lumpy" way.

- The additional cost of a batch of output, not necessarily just one unit.

- Read "the cost of a volunteer military force"

Price elasticity of supply

- Price elasticity of supply is the percentage change in the quantity supplied divided by the percentage change in the price.

- Elasticity is influenced by time.

- Although it takes no time to start demanding less when the price of a good rises, it does take time to start supplying more when the price of a good rises.

- This is why there can be completely inelastic supply curves.

Cost as justification

- The economic analysis of costs can be treacherous because they have an ethical and political dimension.

- Many people seem to believe that sellers have a right to cover their costs, have no right to any price that is significantly above their costs, and are almost surely pursuing some unfair advantage if they price above or below cost.

- Legislated price controls follow this way of thinking.

- This way of thinking is wrong. Cost is always the product of demand and supply.

Summary

- Supply curves as well as demand curves reflect people’s estimates of the value of alternative opportunities. Both the quantities of any good that are supplied, and the quantities that are demanded depend on the economizing choices people make after assessing the opportunities available to them.

- Costs are always the value of the opportunities that particular people sacrifice. Conflicting assertions about the costs of alternative decisions can often be reconciled by agreement on whose costs are under consideration.

- Past expenditures cannot be affected by present decisions: They are sunk costs and hence irrelevant to decision making. All costs relevant to decision making therefore lie in the future.

- Opportunity costs are necessarily marginal costs: They are the additional costs that an action or a decision entails.

- Supply depends on cost. (What doesn’t?) But the cost of supplying is the value of the opportunities forgone by the act of supplying. This concept of cost is expressed in economic theory by the assertion that all costs relevant to decisions are opportunity costs—the value of the opportunities forsaken in choosing one course of action rather than another.

- Supply curves slope upward to the right because higher prices must be offered to resource owners to persuade them to transform a current activity into an opportunity they are willing to sacrifice.

- Anything that alters the marginal cost of production would tend to shift the supply curve. The market supply curve is also subject to shift if the producers’ price expectations change, or if the overall number of producers within an industry changes.

- Price elasticity of supply is the percentage change in the quantity supplied divided by the percentage change in the price.

- Many disagreements about what something “really” costs could be resolved by the recognition that “things” cannot have costs. Only actions entail sacrificed opportunities, and therefore only actions can have costs.

- Never forget to ask yourself “cost to whom?” “cost of doing what?” By so doing, you’ll be well on your way to thinking like an economist.