Week 4 Jan. 30 - Negative Emotions

Disgust

Core disgust have prototypical facial expressions

Moral Disgust

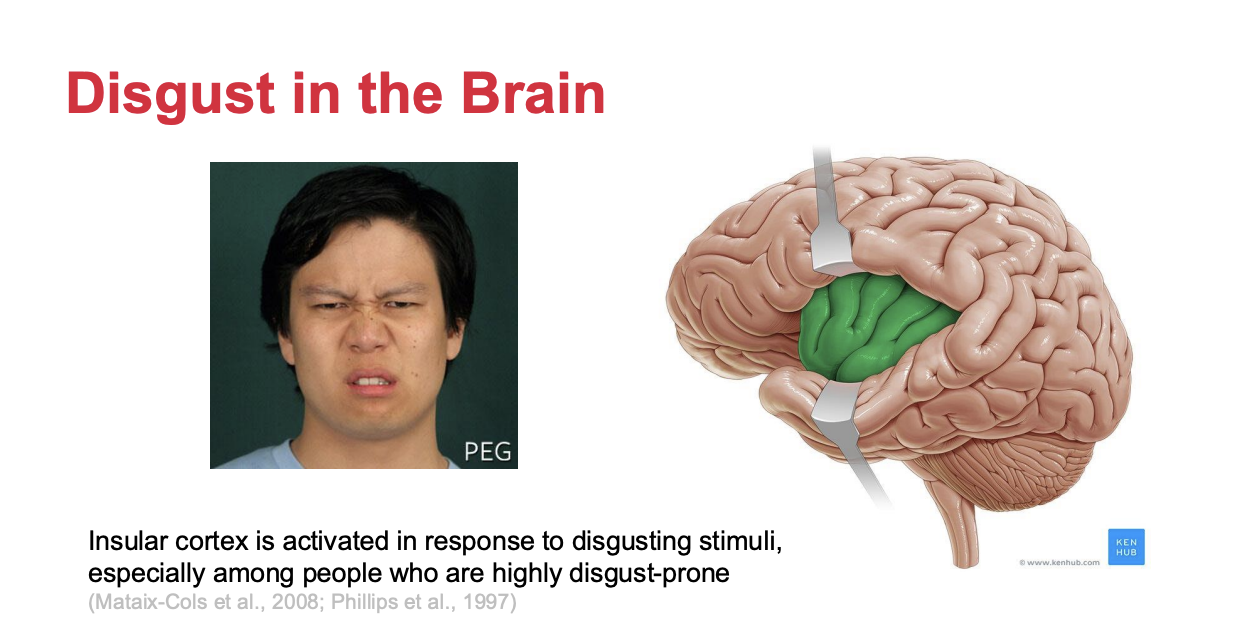

Disgust in the Brain

Interceptions

Disgust proneness is a trait people can possess

Behavioural Immune System

Set of psychological mechanisms

The system is tune in a way where is responds to general cues

Example: Smoke detector alerts you in possible smoke, though it can alert by false positives

Functional Flexibility

More motivated to move

Disgust helps motivate your behaviour

Textbook - Chapter 11

Ideal Affect

The affective states that a person ideally wants to feel and will try to attain

Fear

Learning Objectives

Adaptive function of fear

Fear is an algorithm

Define fear appeal + explain conditions under which fear appeals are most likely to promote actual behaviour change

The role of genes in individual differences in fear proneness

Fear

A response to a specific perceived danger

Anxiety

A general expectation that something bad might happen, without identifying any particular danger

Social Anxiety

Intense anxiety specific to situations involving social interaction

The State Trait Anxiety Inventory

The idea behind this questionnaire is that anxiety is both a state (a temporary condition related to recent events) and a trait (a long term aspect of personality)

Prototypical facial Expression of fear

Includes lifting the inner and outer eyebrows and pulling them together; widening the eyes and contracting the muscles below the corners of the lips, pulling the skin of the lower cheeks down and to the side

Startle response

Innate

Reaction to a sudden loud noise or other strong stimulus in which the muscles tense rapidly, especially the neck muscles, the eyes close tightly, the shoulders quickly pull close to the neck, and the arms pull up toward the head

Input from the rest of the nervous system can modify its intensity. Negative emotions, especially fear and anxiety, tend to amplify the response

The startle response depends on a reflexive response by the pons to sudden, loud noises. The startle response can be augmented or diminished by input from the amygdala, which helps scan information from the environment, assessing whether it is dangerous or safe

Startle Potentiation

Enhancement of the startle response in a frightening situation compared to a safe one

Freezing

A behavioural measure of fear is freezing or suppression of movement

Research in animals

In the presence of a predator’s smell, loud sound, or other indicator of danger, most small animals simply freeze

In one study, researchers induced panic by depriving participants of oxygen in the lab; about 13% reported feeling like they could not move

Other studies have documented reduced movement when participants see a threatening stimulus such as a photograph of a spider

What does fear look like in the brain?

Startle potentiation effect relies on the activation in the amygdala

The amygdala is an area within the temporal lobe of each hemisphere, each amygdala receives input representing vision, hearing and other senses and pain

Each amygdala is connected with a hippocampus, which is important for memory which is important for memory, so it is in a position to associate various stimuli with dangerous outcomes that follow them. Conditioned fears—that is, fears based on the association of some stimulus with shock

Specific sections of the amygdala—the central nucleus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis—appear to play important roles in detecting threats and initiating visceral and behavioral responses associated with fear and anxiety

The Functions of Fear

Fear is elicted by three major categories of stimuli:

Animals

Social threats

Unwanted social attention

Non living threats: heights

Some fears appear to innate:

For example, sudden, loud noises frighten virtually everyone, from birth through old age. That fear is also present in nearly all other animal species that have hearing. Fear of dark places is also common among humans. Separation from loved ones may be another built-in fear, especially for young children

Little Albert

John Watson

A toddler who had never before feared rats

Every time an experimenter showed “Little Albert” a rat, Watson struck a loud going nearby; after a few such pairings, Albert became frightened whenever a rat appeared

Social Fear Learning

Learning to fear a new stimulus based upon seeing another person’s negative experience with it, or their fear response to it

We likely inherit our Predator fear response from ancient, small, mammalian ancestors for whom snakes were the main predator, and we retain the vestiges of this fear

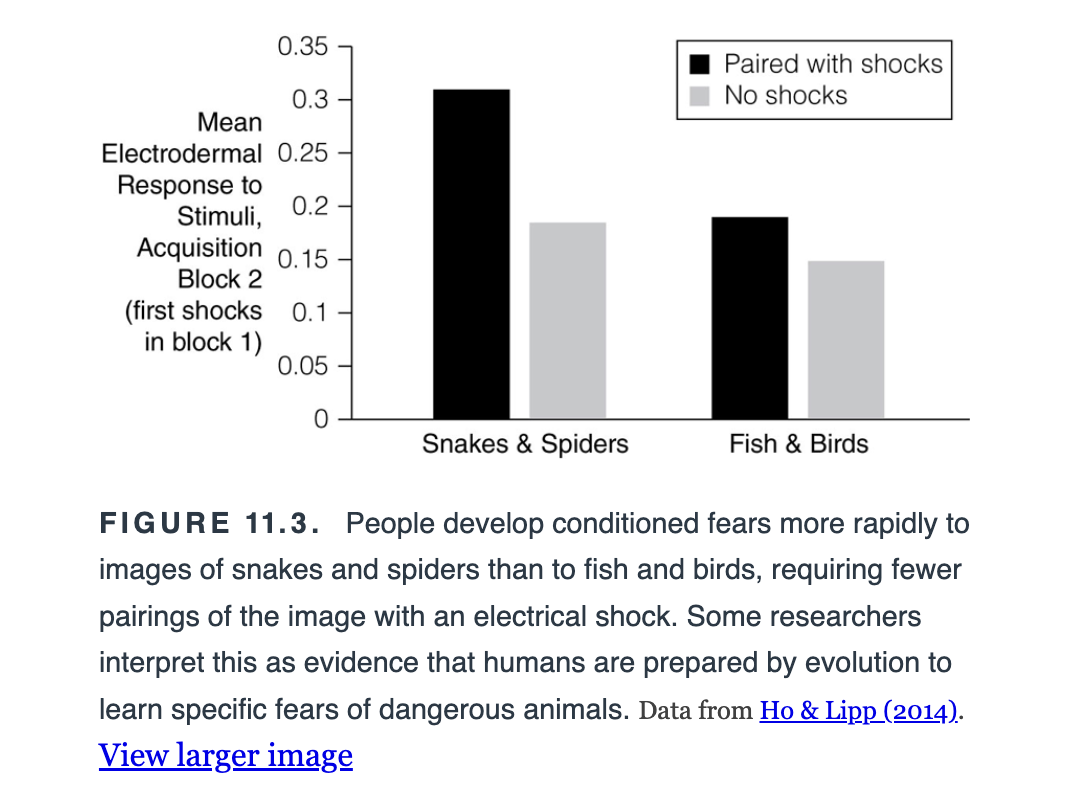

Prepared Learning

Proposal that people and other animals are evolutionarily predisposed to learn some things (including fears) more easily than others

Ordinarily, laboratory-reared monkeys show inhibition and withdrawal from snakes the first time they see one. If nothing bad happens, their fear habituates (declines), but this initial wariness suggests a predisposition toward fear (Nelson, Shelton, & Kalin, 2003). If a monkey sees another monkey show fear of snakes, it acquires the fear too, although the observing monkey has never been bitten or even seen any other monkey bitten

These effects are specific to snakes—if a monkey watches a movie of another monkey running away from a snake, it develops a fear of snakes, but if it watches an edited movie showing a monkey running away from flowers, it develops no fear of flowers

Humans are also quick to learn a fear of snakes

People who get shocks paired with pictures of snakes soon show a conditioned response (increased heart rate and breathing rate), whereas those who get shocks paired with pictures of houses develop weaker responses

if you have safe experiences with something, you're less likely to fear it. People may have been in car accidents or seen them happen, but they also have thousands of safe experiences with cars, which helps balance out any fear. Now, think about how many safe experiences you've had with snakes—probably not as many.

We tend to pay attention to things that stand out, whether they're dangerous or not. Babies, for example, stare at pictures of snakes and spiders, but they don’t look scared—they don’t cry or try to move away. Researchers suggest that humans might just be wired to notice these things, but whether we actually fear them depends on what we learn from others.

Fear is all about helping us avoid danger, and it's not just one simple reaction. Imagine you're walking alone at night, and someone suspicious is following you. You might speed up, hide, run, or even fight back—depending on the situation. Animals do something similar: they freeze if a predator is far away but run if it's getting closer. Scientists study these reactions in both animals and humans to understand how fear works. Instead of being a single feeling, fear is more like a flexible system that helps us respond in the best way to stay safe

Using Fear to Change Behaviour

Fear Appeals

A public service message emphasizing the negative outcomes that are likely if behaviour does not change

Example: magazine advertisements showing diseased lungs and television commercials listing the health risks of smoking are each designed to scare people into healthier behavior, emphasizing the awful things that will happen if people don’t change. Do these appeals actually work?

health-promotion messages including a fear appeal were found to produce more positive attitudes toward the recommended behaviour, greater intention to change, and more actual behavioural change, relative to control conditions

While fear may provide motivation to change one’s behaviour, another crucial ingredient is self-efficacy—the belief that one can actually succeed in doing so

belief that one is capable of doing something that one wants to do, such as changing a problematic behaviour or developing a new skill

fear appeals showed the greatest effects when they were accompanied by clear and specific steps people could take to avoid disaster; and when only one-time action was needed rather than commitment to ongoing, long-term change

The new twist was that another emotion—hope—was associated with both self-efficacy and fear. Moreover, among those reporting high self-efficacy, those who also felt hopeful showed the strongest effects

Individual Differences: Genetics and Fear

The right amount of fear or anxiety depends on your environment. If you live in a peaceful area, you may not need to be as cautious as someone in a dangerous neighborhood. But even in safe places, a little fear can help—like being alert while walking alone at night. Ideally, we should adjust our fear based on the situation.

Genetics also play a role in how much fear or anxiety we feel. Some people are naturally more anxious from a young age, and studies show that anxiety runs in families. Research even suggests that genes influence how easily we learn new fears. For example, identical twins tend to have similar fear responses, even if raised separately.

Scientists are still trying to identify the exact genes responsible for fear. One interesting finding links anxiety to joint laxity (being double-jointed), suggesting there may be a shared genetic basis. However, the connection is not yet fully understood.

While too much fear can be harmful, having no fear at all is also risky. People who are less fearful often underestimate danger and take more risks, sometimes leading to serious consequences—just look at the Darwin Awards! In extreme cases, a lack of fear is linked to psychopathy, which includes impulsive and reckless behavior.

That said, some fear can be good. It keeps us safe but also pushes us to try new things. Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “Do one thing every day that scares you,” meaning that stepping out of our comfort zone helps us grow.

Anger

Learning Objectives

Elicitors and theorized adaptive function of anger, and analyze the evidence for this function

Analyze the evidence regarding effects of anger displays in interpersonal relationships, predicting when and for whom these are likely to be beneficial, rather than backfiring

Differentiate hostile and instrumental aggression, and identify examples of each

Fear and anger have a lot in common:

Both are responses to unexpected, unpleasant events

Both evoke arousal and strong visceral responses

Fear is east to elicit in the laboratory, whereas anger is quite difficult

Anger

The emotional state associated with feeling injured or offended and with a desire to threaten or hurt the person who offended you

Anger is a response to a violation of autonomy

Disgust

A response to a violation of purity or divinity

Researchers made a list of actions that seemed to violate autonomy, community standards or divity/purity

Then they asked college students in both the United States and Japan to label their reaction to each one as anger, contempt, or disgust and to choose the proper facial expression

How is Anger measured?

The Multidimensional Anger Inventory

Includes items capturing appraisals that lead to anger, angry feelings, and the resulting behavior, each of which is important for assessing overall anger-proneness

The Spielberger State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory

focuses largely on intense, somewhat destructive kinds of anger

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory

The STAXI can be used to distinguish between current, state feelings of anger and chronic anger-proneness

The Constructive Anger Behavior-Verbal Style scale

Consists of items that can be filled out either as a self-report or by an observer or interviewer, who presumably provides a less biased account

Prototypical Angry Face

Angry people often push their eyebrows down and toward the middle of their forehead, and they may raise their eyelids to show more of the eye as well. Their lower eyelids pull up and toward the inner corner of the eyes, and lips tighten and/or press together

Anger on your Physiological State

Anger and fear feel similar in the body, but there's one key difference: in fear, blood vessels in your hands and feet tighten, making them cold, while in anger, they expand, keeping your hands warm.

Brain activity also sets anger apart. Most negative emotions, including fear, activate the right side of the frontal cortex, while positive emotions activate the left. But anger follows a different pattern. Research shows that anger is linked to more activity on the left side—similar to positive emotions. This is because emotions aren’t just about feeling good or bad; they also involve motivation. Usually, we move toward things that make us happy and away from things that scare us. However, anger pushes us to take action, especially if we feel we can do something about the situation. That’s why anger is more about control and agency compared to fear

The Functions of Anger

Anger can serve as an important interpersonal function

According to the recalibrational theory of anger

we experience anger when we appraise someone’s behavior toward us as failing to take our welfare sufficiently into account. In other words, they have not treated us with the respect and consideration we feel we deserve

Expressing anger communicates that you expect to be treated better

People who are angry are less likely to take the other person’s perspective

Anger can influence negotiations in surprising ways. Research shows that people tend to make more compromises when facing an angry opponent. However, they also retaliate when given the chance—for example, by assigning unpleasant tasks to their angry partner in a later study.

But anger only works in negotiations if it’s seen as genuine. If someone believes you’re faking anger to gain an advantage, they’re likely to become more demanding

Interestingly, people can override the automatic effects of anger when they’re made aware of their emotions. In one study, simply acknowledging that a video made them angry reduced anger’s impact on their decisions. This suggests that recognizing emotions can help us think more clearly in negotiations

Anger also makes people more self-focused. In one experiment, angry participants were less likely to consider a time zone difference when scheduling a meeting. In other studies, they struggled to explain a chess move from another person's point of view or to recognize how a number appeared from the other side of a table. These effects didn’t happen with sadness or disgust—only anger made people prioritize their own perspective over others

Anger and Aggression

What do you do when your angry?

Not all anger leads to aggression, and not all aggression begins with anger

Psychologists distinguish between hostile and instrumental aggression

Hostile Agression

Harmful behaviour motivated by anger and the events that preceded it

Instrumental Agression

Harmful or threatening behaviour used purely as a way to obtain something or to achieve some end

Examples include bullying, theft, warfare, and killing prey. Much of human aggression is instrumental. For example, social psychologists have found that many normal, healthy, well-intentioned people will inflict pain and suffering on someone they’ve never met, possibly even endanger that person’s life, if an authority figure tells them to

Research

Laboratory studies on aggression help researchers understand human behavior, but they come with important limitations. Since real fights are rare and unethical to provoke, experiments often use deception—like making participants believe they are delivering electric shocks—to measure aggression safely.

However, these studies don’t fully capture real-world aggression. Participants follow rules that require aggression, they don’t know their targets personally, and their actions have no social consequences. Additionally, aggression in these settings might be driven by competition rather than anger.

While these methods offer valuable insights, they don’t always reflect how aggression plays out in daily life. Understanding their limitations helps us interpret research findings more accurately

Individual Differences: Who Benefits from Being Angry?

This passage highlights key gender differences in how anger is perceived and its consequences, particularly in professional settings. Research shows that men tend to express anger more frequently and are often rewarded for it, as their anger is viewed as a sign of power and conviction. In contrast, women’s anger is more likely to be attributed to their personality rather than the situation, leading to negative judgments like being seen as "shrill" or "obnoxious."

This bias can have real-world implications, such as hiring decisions. For example, angry male lawyers are perceived as strong and competent, while angry female lawyers are seen as less hireable. However, research suggests that this bias can be reduced when women clearly justify their anger, making the situational cause explicit.

This underscores the importance of awareness in both expressing and interpreting anger, particularly in professional and social interactions

Disgust

Learning objectives

The elictors and theorized adaptions of disgust

The link between individual differences in disgust proneness and political orientation

The term disgust refers a combination of latin prefix

to taste

Revulsion at the prospect of oral incorporation of offensive objects

Self report Disgust Scale

Assesses intensity of disgust toward several different categories of elicitors

Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Questionnaire

Measures people’s subjective discomfort around possible sources of germs, as well as beliefs about how susceptible one is to infection

Disgust expression intensity shows high correlation (+45) with the personality trait Neuroticism

Meaning tendency to experience unpleasant emotions relatively easily. In other words, people prone to disgust are also prone to sadness and anxiety. Disgust also shows a negative correlation (–.28) with the personality trait Openness to Experience—the tendency to explore new opportunities, such as trying new or unusual types of foods, art, music, literature, and so forth

Physiological Responses associated with disgust

This passage highlights the complex physiological responses associated with disgust, which differ from those of fear and anger. While disgust involves activation of the sympathetic nervous system—leading to increased heart rate, blood pressure, and sweating—it also shows signs of parasympathetic influence, such as changes in heart rhythm and slowed stomach contractions (bradygastria). These physiological effects are linked to nausea and vomiting, reinforcing the body’s protective response to potential contaminants

This dual activation of both sympathetic and parasympathetic systems makes disgust unique compared to other emotions like fear and anger, which primarily involve sympathetic arousal

Different Types of Disgust

Disgust types such as contamination-related and gore-related—can elicit distinct physiological responses. While contamination disgust typically increases heart rate, exposure to gore can cause heart rate to slow, similar to the response seen in blood phobia before fainting. This suggests that what we commonly label as "disgust" might actually involve multiple distinct emotional processes.

The insular cortex, particularly the anterior insula, plays a key role in disgust perception, as it becomes active when people encounter disgusting scents or images. This brain region is also closely linked to taste perception, reinforcing the idea that disgust evolved as a protective mechanism against harmful substances. However, insula activity is not exclusive to disgust—it also responds to fear and general awareness of bodily sensations, suggesting a broader role in emotional and physiological self-awareness

Functions of Disgust

Core Disgust

Emotional response to an object that threatens your physical purity, such as feces, rotting food, or unclean animals

Disgust serves as an adaptive mechanism for avoiding disease and contamination, but it is also shaped by culture and experience. While core disgust—such as revulsion toward feces or rotting food—helps protect us from pathogens, what we find disgusting is not entirely innate. Food preferences and aversions are heavily influenced by cultural norms, learned associations, and even prenatal exposure

The discussion of food neophobia is particularly interesting. While repeated exposure can help people overcome initial aversions, a single negative experience—such as vomiting after eating a specific food—can create a lasting disgust response. This powerful association, often called taste aversion learning, ensures that we quickly learn to avoid potentially harmful substances.

The idea of “magical” contamination thinking further emphasizes how deeply ingrained disgust can be. Even when logically aware that something is safe, people struggle to overcome visceral reactions—for example, refusing to eat chocolate shaped like feces or drink sterilized juice that a cockroach has touched. This psychological rigidity underscores how emotions like disgust are not just about rational risk assessment but also deeply tied to instinctive and learned responses

Moral Disgust

Johnathan Haidt

Began asking 20 people to describe all the intensely disgusting experiences they could remember

Grouped those experiences into categories:

Bad-tasting foods;

Body products such as feces, urine, and nose mucus;

Unacceptable sexual acts, such as incest;

Gore, surgery, and other exposure of the inner body parts;

Sociomoral violations such as Nazis, drunk drivers, hypocrites, and ambulance-chasing lawyers;

Insects, spiders, snakes, and other repulsive animals;

Dirt and germs; and

Contact with dead bodies

People who report disgust one of these categories also tend to be more disgusted by the others

Moral Disgust

Disgust response to violations of moral, rather than physical, purity

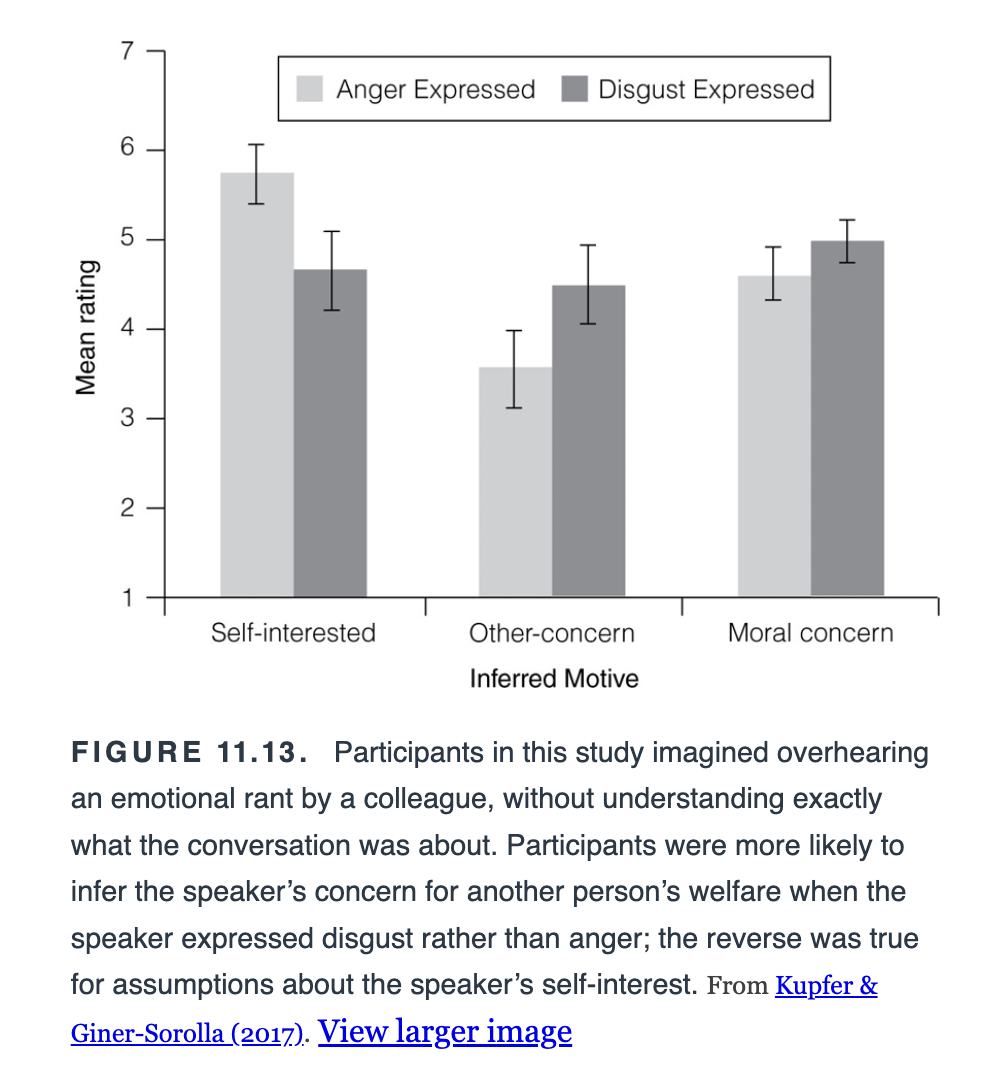

Virtue Signaling

Exhibiting behaviors (including emotional reactions) that advertise ourselves as valuable, norm-following, trustworthy social partners

Moral disgust might be an evolutionary extension of core disgust, repurposed to help us navigate social and moral landscapes. Just as core disgust helps us avoid physical contaminants, moral disgust could serve to protect social "purity" by rejecting individuals or behaviors seen as violating ethical norms.

The idea that moral disgust functions as a form of virtue signaling is particularly compelling. It implies that our expressions of disgust toward moral violations are not just about personal feelings but also about demonstrating to others that we uphold social values. The distinction between disgust and anger in moral judgment—where disgust is more associated with perceived bad intent and anger with harmful outcomes—further supports the idea that different emotions play specific roles in our social interactions.

However, the passage also notes that most studies on moral disgust have been conducted in Western cultures, raising questions about whether these findings generalize across diverse cultural contexts. Since moral values vary widely across societies, it would be interesting to see whether disgust plays the same role in moral judgment universally or if its function is more culture-specific.

Individual Differences: Political Orientation

This passage highlights the complexity of disgust-proneness and its variability across individuals, shaped by factors such as age, gender, genetics, and even political ideology.

The finding that women tend to be more disgust-prone than men aligns with evolutionary theories suggesting that disgust helps protect against pathogens, especially in contexts related to pregnancy and caregiving. The heritability studies further suggest that our sensitivity to disgust isn't just learned but has a genetic basis, making it a stable trait across populations.

The discussion on political ideology and disgust is particularly interesting because it challenges the assumption that conservatives are universally more disgust-sensitive than liberals. While some studies have found that conservatives react more strongly to core disgust (e.g., bodily contamination), the relationship with moral disgust seems to depend on the specific type of moral violation being assessed. For instance, conservatives may be more disgusted by violations of traditional norms (e.g., drug use or disruptions in religious settings), while liberals may be more disgusted by violations related to social justice (e.g., tax evasion or environmental harm). The fact that some studies fail to find a clear link between conservatism and general disgust sensitivity highlights how measurement choices can shape research outcomes.

Overall, this research raises important questions about the role of disgust in shaping both personal and societal attitudes. It suggests that disgust isn't just a biological reflex but also a deeply social and context-dependent emotion that influences—and is influenced by—cultural norms and ideological beliefs

Sadness

Learning objectives

Gender and age related individual differences in susceptibility to sadness

Sadness

An emotional response to a significant and perhaps irrevocable loss

Physiologically

Sadness is not a singular physiological state but instead follows two distinct patterns depending on the context. The first pattern—characterized by increased heart rate, blood pressure, and skin conductance—is more common when sadness is tied to an impending loss, such as watching a loved one dying. This heightened arousal might reflect an attempt to prepare for or even prevent the loss. In contrast, the second pattern—marked by lower heart rate and skin conductance—is more common when a loss has already occurred, suggesting a shift toward energy conservation and withdrawal

The idea that sadness changes over time—from an active, anticipatory response to a more passive, resigned state—is compelling. It aligns with models of grief, which propose that initial emotional responses to loss are often intense and effortful but gradually shift toward acceptance and low-energy reflection. The suggestion that different types of loss (social vs. material) might trigger different physiological responses is also interesting, though further research is needed to confirm this distinction

This variability in sadness-related arousal highlights the complexity of emotional experience. Unlike emotions such as fear, which tend to show more consistent physiological patterns, sadness appears to have multiple manifestations depending on the situation. Future research exploring these differences could provide valuable insights into how we process and cope with loss across different contexts

Pathology

If sadness is evolutionarily adaptive, what purpose does it serve? While sadness is often linked to depression, it likely plays a functional role in human survival and social behavior.

One possibility is that sadness promotes social bonding. Expressions of sadness signal distress to others, eliciting support and care from friends and family. This could explain why visible signs of sadness, such as crying, are more common in response to social losses than material losses. Another potential function is cognitive recalibration—when faced with failure or loss, sadness may encourage withdrawal and reflection, helping individuals learn from past experiences and adjust future behaviour.

However, if sadness becomes chronic or overwhelming, it can interfere with daily functioning, leading to depression. This raises the question of whether depression is an extension of sadness that has lost its adaptive function or if it serves a different, yet still unknown, purpose. Understanding the distinction between normal sadness and pathological sadness is crucial for both psychological research and clinical interventions

The Functions of Sadness

Ad Vingerhoets and colleagues

Participants from the Netherlands and the United States were shown photographs of people expressing sadness. There were two experimental conditions:

Tears Visible Condition – Participants saw images of individuals with tears on their faces.

Tears Removed Condition – The same images were digitally altered to remove the tears, leaving only the facial expression of sadness

People with visible tears were perceived as needing more social support than those without tears.

Participants reported feeling stronger sympathy and emotional connection toward individuals with tears.

The presence of tears increased participants' willingness to offer help to the crying individuals

These results suggest that tears serve as a powerful social signal that enhances empathy and motivates prosocial behavior. While a sad facial expression alone can indicate distress, the addition of tears strengthens the perception that someone needs comfort and assistance. This supports the idea that crying evolved as a mechanism to elicit social support from others, reinforcing human social bonds

When people are in a sad mood, they process information more carefully and systematically

Example: When compared with angry people, sad people rely less on cognitive shortcuts, such as stereotypes in perceiving new social targets

People in a sad mood are also less likely to show a false memory, in which they report having seen a word related conceptually to several others on a list they were give to remember

Does Crying Make You Feel Better?

When you’re upset the best thing to do is express your feeling to the fullest

Comes from Freud’s idea of Catharsis

The release of strong emotions by expressing them

The idea is that the emotions are trapped inside you and must come out somehow

Evidence on “does crying make you feel better?” there are mixed evidence on this

People often report feeling better after crying in surveys, but laboratory studies typically find that people feel worse immediately after crying. This discrepancy can be explained by several factors.

First, timing plays a crucial role. In most lab studies, mood is measured immediately after crying, often following an emotional stimulus like a sad film. Right after crying, people may still feel distressed or overwhelmed. However, research by Gracanin et al. (2015) found that after 90 minutes, frequent criers reported feeling better. This suggests that the benefits of crying take time to emerge, likely due to emotional regulation processes.

Second, social context matters. In real-life situations, people often cry in the presence of others who offer comfort, such as kind words or physical touch. A diary study by Bylsma et al. (2011) found that women were more likely to feel better after crying when another person was present and the situation improved afterward. In contrast, laboratory settings lack these supportive social factors, which may make crying feel more isolating.

Individual differences also play a role. People who are prone to depression tend to feel worse after crying (Rottenberg et al., 2008), possibly because crying triggers rumination rather than relief. Other factors, such as personality traits and cultural norms, may also influence whether crying leads to emotional relief or distress.

Finally, methodological limitations may contribute to the mixed findings. Many studies rely on self-reports, which can be influenced by memory biases—people might recall feeling better after crying because they associate it with emotional release, even if they didn’t experience immediate relief. Additionally, studies rarely assign participants to crying or non-crying conditions randomly, making it difficult to determine whether emotional differences are due to crying itself or the effort of suppressing tears.

Overall, while crying might not provide immediate relief, it can be emotionally beneficial over time, particularly in supportive social environments. The emotional outcome of crying depends on when, where, and with whom it happens

Individual Differences: Aging and Loss

Research on individual differences in sadness is more limited compared to other negative emotions, but some patterns have emerged. Globally, women are more likely than men to report and express sadness (Choti et al., 1987; Fischer et al., 2004). This aligns with gender norms, as sadness is associated with low control (Scherer, 1997) and vulnerability, while men are often expected to project strength and power.

One particularly interesting difference in sadness relates to aging. Although older adults generally experience fewer negative emotions (Carstensen et al., 2000), they report stronger feelings of sadness in response to emotionally evocative stimuli, such as films depicting social loss (Kunzmann & Grühn, 2005; Seider et al., 2011). Physiologically, their emotional responses to sadness are also more pronounced than those of younger adults, with stronger arousal patterns that align closely with their subjective feelings (Lohani, Payne, & Isaacowitz, 2018). Notably, this effect appears unique to sadness and does not extend to other negative emotions like disgust.

There are a few possible explanations for why sadness intensifies with age. One possibility is that older adults have more life experience with loss and better understand its significance. Another is that losses may feel more consequential as people age since their social circles tend to shrink over time. Despite its increased intensity, sadness in older adults is not necessarily harmful. In fact, research suggests that greater sadness intensity is linked to higher psychological well-being in later life (Haase et al., 2012), possibly because it fosters deeper social connections.

As the movie Inside Out illustrates, sadness plays a vital role in emotional processing and social bonding. Just as Joy comes to appreciate its value in Riley’s life, we too might recognize sadness as an essential and meaningful part of human experience

Embarrassment, Shame, and Guilt

Self Conscious Emotions

Emotions such as embarrassment, shame, and guilt that require appraisal of yourself and how you appear to others

The Functions of Embarrassment, Shame and Guilt

Researchers agree that all these emotions serve related functions: they help us to repair relationships we may have damaged through some mistake or transgression

Researchers have explored whether embarrassment, shame, and guilt are distinct emotions or simply different labels for the same experience. One approach to differentiating them is to examine the situations that typically elicit each emotion. In a study with U.S. college students, participants were asked to recall personal experiences of embarrassment, shame, and guilt (Keltner, 1995).

Embarrassment was most commonly linked to situations involving poor performance, physical clumsiness, cognitive errors (such as forgetting a name), inappropriate appearance, privacy violations, being teased, and feeling overly conspicuous. These experiences often involve unintentional mistakes and social awkwardness.

Shame, on the other hand, was frequently associated with poor performance (similar to embarrassment) but also with actions that violated personal or social expectations. Participants recalled feeling shame after hurting someone's feelings, lying, or failing to meet their own or others’ expectations, such as disappointing their parents with low grades. Unlike embarrassment, which arises from social missteps, shame often involves a deeper sense of personal failure and self-judgment.

Guilt was most commonly linked to moral transgressions and failures in personal responsibility. Participants reported feeling guilty for not fulfilling obligations, lying, cheating, neglecting loved ones, infidelity, and breaking commitments like dieting. Unlike shame, which is tied to a negative self-evaluation, guilt tends to focus on specific behaviors and may motivate corrective action.

These findings suggest that while embarrassment, shame, and guilt share some similarities, they arise from distinct experiences and have different interpersonal effects. Embarrassment typically stems from social awkwardness, shame from perceived personal failures, and guilt from moral lapses

Embarrassment

The emotion felt when one violates a social convention, thereby drawing unexpected social attention and motivating submissive, friendly behaviour that should appease other people

Shame

The emotion felt when one fails or does something morally wrong and then focuses on one’s own global, stable inadequacies in explaining the transgression

Guilt

The negative emotion felt when one fails or does something morally wrong but focuses on how to make amends and how to avoid repeating the transgression

In one study

participants evaluated apologies from individuals caught in serious transgressions, such as cheating on a test or lying. When the offenders displayed shame rather than embarrassment in their facial expressions, they were perceived as more sincere and were more likely to be forgiven (Thorstenson, Pazda, & Lichtenfield, 2020). This suggests that embarrassment may signal a lack of seriousness about the wrongdoing, whereas shame indicates a deeper acknowledgment of the transgression.

While shame and guilt often arise from similar situations, they differ in how individuals interpret their actions. Research suggests that shame is linked to negative self-perceptions, where individuals view themselves as inherently bad or unworthy. This perspective involves internal, stable, and global attributions—people experiencing shame might think, "I'm so stupid." In contrast, guilt is tied to specific behaviors rather than self-worth, leading individuals to focus on regretting their actions rather than their character (Niedenthal, Tangney, & Gavanski, 1994). For example, a person feeling guilt might think, "I shouldn’t have done that."

The Blush of Embarrassment

The most distinctive aspect of the embarrassment expression is the blush

A temporarily increased blood flow to the face, neck, and upper chest

Study

Participants were asked to complete a stressful quiz in the presence of an experimenter, and then did a self disclosure task while the experimenter either maintained eye contact, wore sunglasses or left the room

Participants in all conditions blushed during the difficult quiz, consistent with the proposal that anxiety can elicit blushing

During the self disclosure task only those who maintained eye contact with the experimenter continued to blush, despite reporting lower levels of anxiety than participants despite reporting lower levels of anxiety than participants in the other conditions

This suggests that simply being the focus of others’ attention can elicit a blush response

Evidence

Suggests that blushing helps bring people back to our side

Meaning when people see someone blushing after an error, they perceive them more positively compared to someone who does not blush

Blushing appears to signal genuine remorse, making the person’s apology seem more sincere increasing the likelihood of forgiveness

Individual Differences: Culture and the Meaning of Shame

Daniel Sznycer

Asked participants to read scenarios involving a variety of actions

Some participants were asked to rate how negatively they would view the actor if it were another person