Week 11 PSY10007 - Lecture and Module Videos - Neuropsychology

Concise Version

Week 11: Neuropsychology

Content is in the additional Bernstein e-text.

Overview of Neuropsychology

Definition: Neuropsychology explores the relationship between brain processes, human behavior, and psychological functioning.

Distinction: Focuses specifically on brain processes, unlike psychophysiology or biopsychology, which consider other physiological functions (e.g., heart rate, cortisol levels).

Assumptions:

Complex mental tasks involve separable subtasks.

Different psychological processes are controlled by different brain regions or combinations thereof.

Subfields:

Clinical Neuropsychologists: Use test batteries to understand client neuropsychological processes, detect brain damage or dysfunction by assessing functional perspectives of memory and speech production. They work with neurologists and can detect issues not easily seen through structural brain imaging.

Experimental Neuropsychologists: Investigate brain function and behavior using imaging techniques (EEG, fMRI, PET) alongside cognitive tests. They assess brain mechanisms.

History of Neuropsychology

1800s Dominant View: The brain worked as a single unified organ.

Frans Gaul:

Rejected the unified organ view.

Suggested specific brain regions control different aspects of mental life.

Proposed that brain areas for specific functions grow with exercise (like muscles).

Created a brain map and suggested measuring skull bumps to determine psychological makeup (phrenology).

Phrenology was largely ridiculed.

Paul Broca:

Discovered lesions in the left frontal cortex of patients with speech production problems (Broca's area, Brodmann's areas 44 and 45).

His discovery renewed consideration of localization of function.

Modern Understanding: Specific psychological functions are affected by damage to specific brain regions.

Modules and Networks: Neuropsychologists explore the human brain and behavior through modules (brain regions responsible for specific functions) and networks (inputs and outputs across the network).

Disconnection Syndrome

Brain damage in the left occipital lobe and corpus callosum prevents visual information from entering the left hemisphere.

Patients can write because the left hemisphere's writing regions are intact.

They cannot read what they write because visual feedback cannot reach the language processing systems in the left hemisphere.

Lesion Analysis

Involves understanding localization of function by looking at the results of brain damage.

Determine all abilities needed to complete a task and identify which have been dissociated.

Example - Personal experience:

Postoperative stroke affecting the right occipital lobe.

Experienced dizziness and vision loss in the lower-left quadrant.

MRI confirmed a lesion in that area.

No ongoing deficits after recovery.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Involves a battery of tests assessing memory, reading, and intelligence.

Can be personalized or standardized.

Both approaches are used to pinpoint difficulties in the brain.

Training in Neuropsychology

Requires a master's or Ph.D., typically in clinical psychology, with a focus in neuropsychology.

Licensing requires an internship or supervised practice.

Clinical neuropsychologists work in hospitals diagnosing and treating brain disorders.

Experimental neuropsychologists conduct research and teach in universities.

Mechanisms of Brain Dysfunction

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke): Loss of blood supply to part of the brain, disrupts behavior or mental processes.

Second leading cause of death in Australia.

Often accompanied by little or no pain, leading to delayed treatment.

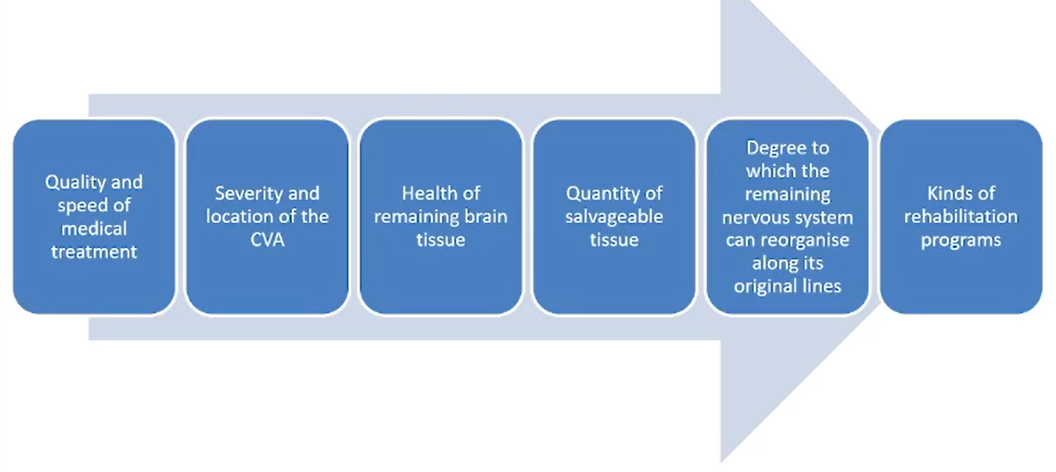

Factors in Recovery from Stroke:

Quality and speed of medical attention.

Severity and location of the stroke.

Health of remaining brain tissue.

Quantity of salvageable tissue.

The degree to which the remaining nervous system can reorganise along its original lines.

Rehabilitation programs.

Traumatic Brain Injury: Impact on the brain caused by a blow or sudden violent movement of the head.

The brain slides within the cerebrospinal fluid and hits the skull, damaging the nerves.

The force of trauma determines the amount of damage to the brain, and damage can be widespread.

Concussions are a common example where the brain collides with the inside of the skull.

Helmets and headgear are largely ineffective against concussions.

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Gradual brain cell damage usually caused by disease.

Examples: Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's disease.

Other causes: Infections, nutritional deficits, and genetic abnormalities.

Parkinson's: Motor function problems and tremors.

Alzheimer's: Memory problems.

Huntington's: Movement, mood, and cognitive deficits.

Anterograde Amnesia: Difficulty forming new long-term memories after damage to the hippocampus.

Examples in movies: 50 First Dates and Memento.

Famous case: Patient H.M., who underwent surgery for epilepsy which eliminated seizures but also the ability to form new long-term memories.

Patients can still learn new skills but cannot remember learning them.

Consciousness Disturbances: Impairments in the ability to be conscious or accurately aware of the world.

Disruption or damage to the reticular formation may lead to coma, persistent vegetative state (PVS), delirium, or anosognosia.

PVS: People may be able to open their eyes and appear conscious at times but mostly remain unaware of their environment.

Delirium: Characterized by abnormal levels of consciousness which can be elevated or impaired.

Impaired consciousness includes poor attention and disorientation.

Elevated levels of consciousness include hallucinations and periods of mental agitation.

Causes: Infections, poisons, fever, medication side effects.

Anosognosia: The inability to recognize an impairment in functioning.

More common after damage to the right hemisphere of the brain.

Occurs in about 25% of stroke victims.

Patients are unlikely to seek medical treatment because they are unaware of the problem.

Perceptual Disturbances

Impairments in the ability to organize, recognize, interpret, and make sense of incoming sensory information.

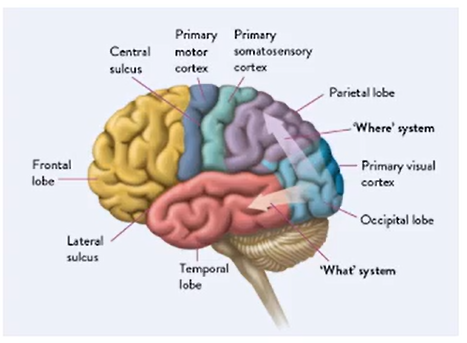

May result from damage to the "what" system (temporal lobe) or the "where" system (parietal lobe).

"What" Pathway (Temporal Lobe):

Visual Agnosia: Inability to identify objects by their appearance but able to see, describe and draw them.

Prosopagnosia: Inability to recognize faces, even one's own reflection.

"Where" Pathway (Parietal Lobe):

Simultaneous Agnosia: Ability to see parts of a visual scene but difficulty perceiving the whole scene.

Hemineglect: Difficulty seeing, responding to, or acting on information coming from one side of the world.

People with hemineglect may see both sides of the world but pay attention to one side while ignoring the other.

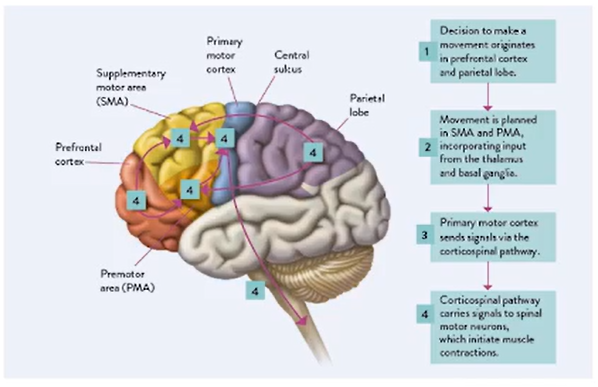

Movement Disorders

Involve impairments in the ability to perform or coordinate previously normal motor skills.

Ideational Apraxia: The sequence of events required to complete a task is incorrect.

Idiomotor Apraxia: Difficulties in performing the skilled movements or the motor commands of a task.

Dementia

A significant and disruptive impairment in memory, perceptual ability, language, or learned motor skills.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) can be a precursor to dementia.

Each year 2-10% of people with MCI develop dementia.

Alzheimer's Disease: A progressive neurodegenerative disorder.

Involves brain abnormalities, including tangles and amyloid plaques.

Affects neurons that use acetylcholine.

Affects the ability to form new memories.

Can lead to anomia (difficulty naming objects) and visual agnosia.

Diagnosing Alzheimer's Disease: Molecular and brain imaging, EEG brain waves, refined neuropsychological assessment batteries can reveal patterns to determine the type of dementia.

Frontotemporal Degeneration: Requires three or more subtle neurological abnormalities, inability to smell certain types of odors, and loss in the ability to appreciate sarcasm.

Treating Alzheimer's: Drug treatments are available, and transdermal patches can provide automatic doses of the correct medication due to patient forgetfulness.

Vascular Dementia: Caused by restrictions in the brain's blood supply, leading to progressive loss of brain tissue.

People with vascular dementia have difficulty in formatting new memories, though the hippocampus may remain undamaged.

Neuroscience: An Interdisciplinary Field

Neuroscience is diverse, ranging from the electrical and chemical communication of individual neurons to how clusters of millions of neurons produce behaviors, thoughts, and feelings.

Scientists in the field come from biology, human biology, artificial intelligence, computer science, and psychology.

The field has emerged over the last thirty years with studies of lesions in humans and animals to understand the functions of different brain areas.

Advances in computer technologies have enabled non-invasive methods like EEG, magnetic resonance imaging, and diffusion tensor imaging to observe brain activity.

Neuroscience addresses questions such as:

How to stop oneself from eating unhealthy foods.

What brain areas underlie sadness and happiness.

The neurological basis of empathy and morality.

The Future of Neuroscience

The future involves:

Translating basic research to help others.

Using neuromodulation.

Developing robotic limbs controlled by brain signals.

Regrowing axons in the spinal cord for individuals with paralysis.

Detailed Version

Week 11: Neuropsychology

Content is in the additional Bernstein e-text.

Overview of Neuropsychology

Definition: Neuropsychology is the study of the relationship between brain processes, human behavior, and psychological functioning. It seeks to understand how the structure and function of the brain relate to specific psychological processes.

Distinction: Neuropsychology focuses on brain processes, differing from psychophysiology or biopsychology, which consider broader physiological functions like heart rate and cortisol levels.

Assumptions:

Complex Mental Tasks: Involve separable subtasks that can be studied individually.

Localization of Function: Different brain regions or combinations control psychological processes. This means specific areas of the brain are responsible for specific functions.

Subfields:

Clinical Neuropsychologists:

Role: Use test batteries to understand a client's neuropsychological processes.

Goal: Detect brain damage or dysfunction through functional assessments of memory and speech production.

Collaboration: Work with neurologists to identify issues that may not be apparent through structural brain imaging alone.

Assessment Techniques: Clinical neuropsychologists use detailed cognitive tests combined with behavioral observations to assess the impact of brain disorders on cognitive and emotional functions.

Experimental Neuropsychologists:

Role: Investigate brain function and behavior using imaging techniques such as EEG, fMRI, and PET alongside cognitive tests.

Focus: Assess brain mechanisms and how they relate to behavior. Experimental neuropsychologists often conduct research to advance the understanding of neural correlates of cognitive processes.

Research Methods: Involve experimental designs to explore how specific brain regions contribute to cognitive functions. This may include studying the effects of lesions, pharmacological manipulations, or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) on cognitive performance.

History of Neuropsychology

1800s Dominant View: The brain was viewed as a single unified organ, with no specific areas dedicated to particular functions.

Frans Gaul:

Rejection of Unified Organ View: Challenged the prevailing view, suggesting specific brain regions control different aspects of mental life.

Localization Theory: Proposed that brain areas for specific functions grow with exercise (like muscles), leading to his development of phrenology.

Phrenology:

Brain Map: Created a map suggesting skull bumps could determine psychological makeup.

Ridicule: Phrenology was largely ridiculed by the scientific community but set the stage for further investigations into brain localization.

Paul Broca:

Discovery: Discovered lesions in the left frontal cortex of patients with speech production problems (Broca's area, Brodmann's areas 44 and 45).

Significance: His discovery renewed consideration of localization of function, indicating that damage to specific brain areas could result in specific functional deficits.

Modern Understanding: Specific psychological functions are affected by damage to specific brain regions, supporting the concept of modular brain organization.

Modules and Networks:

Modules: Brain regions responsible for specific functions.

Networks: Inputs and outputs across the network that neuropsychologists explore to understand human brain and behavior.

Integration: These modules and networks work together to produce complex behaviors, with each region contributing specialized processing and interacting with other regions.

Disconnection Syndrome

Description: Occurs when brain damage in the left occipital lobe and corpus callosum prevents visual information from entering the left hemisphere.

Symptoms: Patients can write because the left hemisphere's writing regions are intact, but they cannot read what they write because visual feedback cannot reach the language processing systems in the left hemisphere.

Explanation: The disconnection prevents visual information from being integrated with language processing areas, resulting in an inability to read what is written.

Lesion Analysis

Definition: Understanding localization of function by looking at the results of brain damage.

Process: Determine all abilities needed to complete a task and identify which have been dissociated due to the lesion.

Personal Experience Example:

Postoperative Stroke: Affected the right occipital lobe.

Symptoms: Experienced dizziness and vision loss in the lower-left quadrant.

Confirmation: MRI confirmed a lesion in that area.

Recovery: No ongoing deficits after recovery, demonstrating the potential for the brain to compensate for localized damage.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Description: A battery of tests assessing memory, reading, and intelligence.

Approaches:

Personalized: Tailored to the individual's specific needs and history.

Standardized: Administered and scored in a consistent manner across individuals.

Objective: Both approaches pinpoint difficulties in the brain by evaluating cognitive and behavioral functions.

Test Examples

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS): Assesses intellectual functions.

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST): Evaluates executive functions, such as cognitive flexibility.

Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test: Assesses visuospatial constructional ability and memory.

Training in Neuropsychology

Education: Requires a master's or Ph.D., typically in clinical psychology, with a focus on neuropsychology.

Licensing: Requires an internship or supervised practice to gain clinical experience.

Career Paths:

Clinical Neuropsychologists: Work in hospitals diagnosing and treating brain disorders, providing rehabilitation services, and conducting forensic evaluations.

Experimental Neuropsychologists: Conduct research and teach in universities, advancing the understanding of brain-behavior relationships.

Mechanisms of Brain Dysfunction

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke):

Definition: Loss of blood supply to part of the brain, disrupting behavior or mental processes.

Impact:

Second leading cause of death in Australia.

Often accompanied by little or no pain, leading to delayed treatment.

Types of Stroke:

Ischemic Stroke: Caused by a blockage in a blood vessel, depriving brain tissue of oxygen and nutrients.

Hemorrhagic Stroke: Occurs when a blood vessel ruptures, causing bleeding into the brain tissue.

Factors in Recovery from Stroke:

Quality and speed of medical attention.

Severity and location of the stroke.

Health of remaining brain tissue.

Quantity of salvageable tissue.

The degree to which the remaining nervous system can reorganise along its original lines.

Rehabilitation programs.

Neuroplasticity: The ability of the brain to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neuroplasticity allows the brain to compensate for injury and adjust to new situations or changes in the environment.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI):

Definition: Impact on the brain caused by a blow or sudden violent movement of the head.

Mechanism: The brain slides within the cerebrospinal fluid and hits the skull, damaging the nerves.

Severity: The force of trauma determines the amount of damage to the brain, and damage can be widespread.

Concussions: A common example where the brain collides with the inside of the skull.

Prevention: Helmets and headgear are largely ineffective against concussions but can prevent more severe forms of TBI.

Diffuse Axonal Injury: Damage to nerve cells scattered throughout the brain's white matter, often resulting from rotational forces during a TBI.

Neurodegenerative Diseases:

Definition: Gradual brain cell damage usually caused by disease.

Examples: Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's disease.

Other Causes: Infections, nutritional deficits, and genetic abnormalities.

Specific Diseases:

Parkinson's: Motor function problems and tremors due to the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain.

Alzheimer's: Memory problems associated with the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

Huntington's: Movement, mood, and cognitive deficits resulting from the degeneration of neurons in the basal ganglia.

Anterograde Amnesia:

Definition: Difficulty forming new long-term memories after damage to the hippocampus.

Examples in Movies: 50 First Dates and Memento.

Famous Case: Patient H.M., who underwent surgery for epilepsy which eliminated seizures but also the ability to form new long-term memories.

Implicit Learning: Patients can still learn new skills but cannot remember learning them, indicating a dissociation between declarative and procedural memory systems.

Consciousness Disturbances:

Definition: Impairments in the ability to be conscious or accurately aware of the world.

Causes: Disruption or damage to the reticular formation may lead to coma, persistent vegetative state (PVS), delirium, or anosognosia.

Specific Disturbances:

PVS: People may be able to open their eyes and appear conscious at times but mostly remain unaware of their environment.

Delirium:

Description: Characterized by abnormal levels of consciousness which can be elevated or impaired.

Impaired Consciousness: Includes poor attention and disorientation.

Elevated Levels of Consciousness: Include hallucinations and periods of mental agitation.

Causes: Infections, poisons, fever, medication side effects.

Anosognosia:

Definition: The inability to recognize an impairment in functioning.

Prevalence: More common after damage to the right hemisphere of the brain.

Occurrence: Occurs in about 25% of stroke victims.

Impact: Patients are unlikely to seek medical treatment because they are unaware of the problem.

Perceptual Disturbances

Definition: Impairments in the ability to organize, recognize, interpret, and make sense of incoming sensory information.

Pathways: May result from damage to the "what" system (temporal lobe) or the "where" system (parietal lobe).

"What" Pathway (Temporal Lobe):

Visual Agnosia: Inability to identify objects by their appearance but able to see, describe and draw them.

Prosopagnosia: Inability to recognize faces, even one's own reflection.

"Where" Pathway (Parietal Lobe):

Simultaneous Agnosia: Ability to see parts of a visual scene but difficulty perceiving the whole scene.

Hemineglect:

Description: Difficulty seeing, responding to, or acting on information coming from one side of the world.

Attention Bias: People with hemineglect may see both sides of the world but pay attention to one side while ignoring the other.

Movement Disorders

Definition: Involve impairments in the ability to perform or coordinate previously normal motor skills.

Types:

Ideational Apraxia: The sequence of events required to complete a task is incorrect.

Idiomotor Apraxia: Difficulties in performing the skilled movements or the motor commands of a task.

Dementia

Definition: A significant and disruptive impairment in memory, perceptual ability, language, or learned motor skills.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI): Can be a precursor to dementia.

Progression: Each year 2-10% of people with MCI develop dementia.

Alzheimer's Disease:

Description: A progressive neurodegenerative disorder.

Brain Abnormalities: Involves brain abnormalities, including tangles and amyloid plaques.

Neurotransmitter Effects: Affects neurons that use acetylcholine, leading to cognitive deficits.

Memory Impairment: Affects the ability to form new memories.

Language Difficulties: Can lead to anomia (difficulty naming objects) and visual agnosia.

Diagnosing Alzheimer's Disease: Molecular and brain imaging, EEG brain waves, refined neuropsychological assessment batteries can reveal patterns to determine the type of dementia.

Frontotemporal Degeneration: Requires three or more subtle neurological abnormalities, inability to smell certain types of odors, and loss in the ability to appreciate sarcasm.

Treating Alzheimer's: Drug treatments are available, and transdermal patches can provide automatic doses of the correct medication due to patient forgetfulness.

Vascular Dementia:

Cause: Caused by restrictions in the brain's blood supply, leading to progressive loss of brain tissue.

Memory Impact: People with vascular dementia have difficulty in formatting new memories, though the hippocampus may remain undamaged.

Neuroscience: An Interdisciplinary Field

Scope: Neuroscience is diverse, ranging from the electrical and chemical communication of individual neurons to how clusters of millions of neurons produce behaviors, thoughts, and feelings.

Contributors: Scientists in the field come from biology, human biology, artificial intelligence, computer science, and psychology.

Emergence: The field has emerged over the last thirty years with studies of lesions in humans and animals to understand the functions of different brain areas.

Technological Advances: Advances in computer technologies have enabled non-invasive methods like EEG, magnetic resonance imaging, and diffusion tensor imaging to observe brain activity.

Key Questions: Neuroscience addresses questions such as:

How to stop oneself from eating unhealthy foods.

What brain areas underlie sadness and happiness.

The neurological basis of empathy and morality.

The Future of Neuroscience

Key Directions:

Translating basic research to help others.

Using neuromodulation to

Images