Chapter 7

Cultural Transformations

Religion and Science

1450-1750

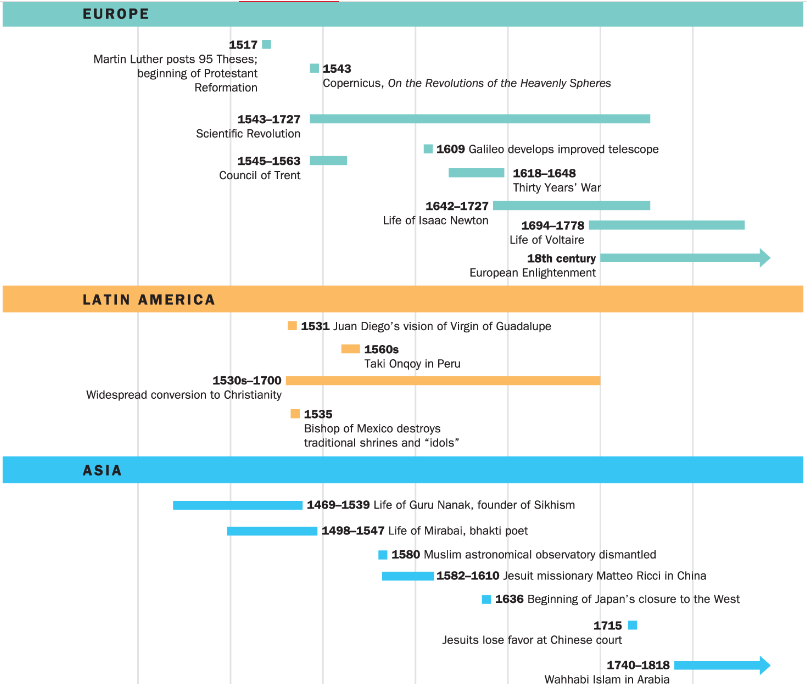

INTRODUCTION:

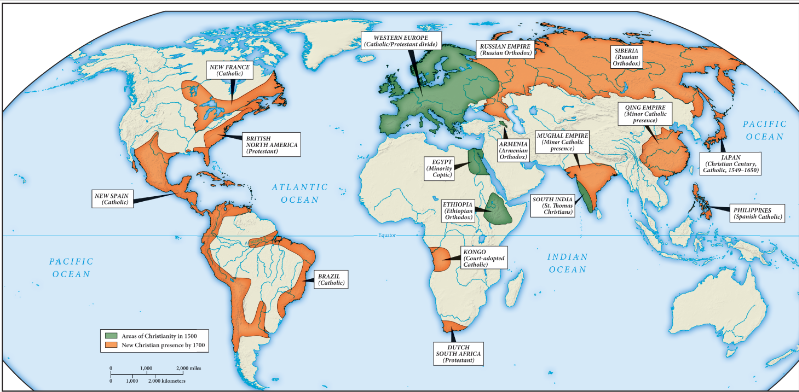

New empires and new patterns of commerce saw cultural and religious transformations that connected distant peoples. During European empire building and commercial expansion, ==Christianity was established in the Americas and the Philippines and in Siberia, China, Japan, and India==. Islam and Christianity contradict one another. While Christianity was spreading, a new understanding of the universe and a new knowledge among European thinkers of the Scientific Revolution, that gave rise to that between science and religion. Science was a new and competing worldview, and for some it became almost a new religion. In time, it grew into a defining feature of global modernity, achieving a worldwide acceptance that exceeded that of Christianity or any other religious tradition.

LANDMARKS FOR CHAPTER 7:

Key Factors:

- Asian, African, and Native American peoples largely determined how Christianity would be accepted, rejected, or transformed as it entered new cultural environments.

- Islam continued a long pattern of religious expansion and renewal, even as Christianity began to compete with it as a world religion.

The Globalization of Christianity:

In 1500, the world of Christendom stretched from the Iberian Peninsula and British Isles in the west to Russia in the east, with small and beleaguered communities of various kinds in Egypt, Ethiopia, southern India, and Central Asia.

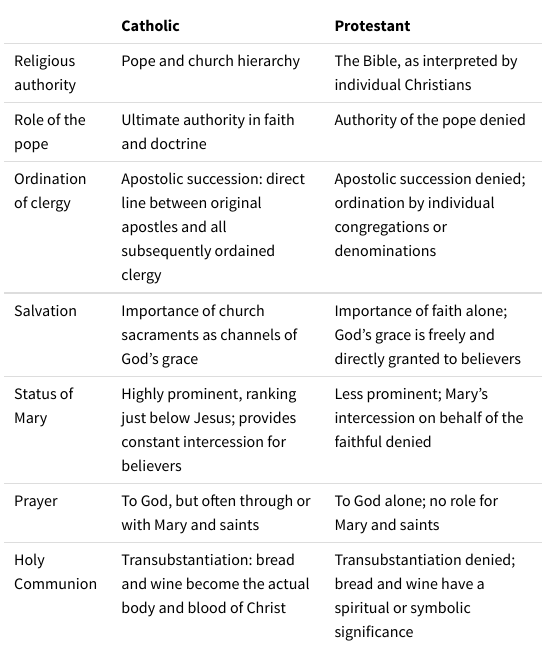

Internally:

Christian world was seriously divided between the Roman Catholics of Western and Central Europe and the Eastern Orthodox of Eastern Europe and Russia.

Externally:

It was very much on the defensive against an expansive Islam.

- Muslims had outed Christian Crusaders from their Holy Land(Jerusalem) by 1300, and with the Ottoman seizure of Constantinople in 1453, they had captured the capital of Eastern Orthodoxy. The Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529 marked a Muslim advance into the Central of Europe. Except in Spain and Sicily, which had recently been reclaimed for Christendom after centuries of Muslim rule, lay with Islam rather than Christianity.

Western Christendom Fragmented: The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation:

The Protestant Reformation shattered the unity of Roman Catholic Christianity, which for the previous 1,000 years had provided the cultural and organizational foundation of an emerging Western European civilization.

Beginning:

The Reformation began in 1517 when a German priest, Martin Luther (1483–1546), publicly invited debate about various abuses within the Roman Catholic Church by making the Ninety-Five Theses, nailing it to the door of a church in Wittenberg. In itself, this was nothing new, for many had long been critical of the luxurious life of the popes, the corruption and immorality of some clergy, the Church’s selling of indulgences (said to remove the penalties for sin), and other aspects of church life and practice.

Martin Luther:

A troubled and brooding man anxious about his relationship with God, Luther had recently come to a new understanding of salvation that came through faith alone. He believed that no blessing of the church stood against he only word of god, and practicing Christianity already put you in heaven. All of this challenged the authority of the Church and called into question the special position of the clerical hierarchy and of the pope in particular. This gave to a “revolution”.

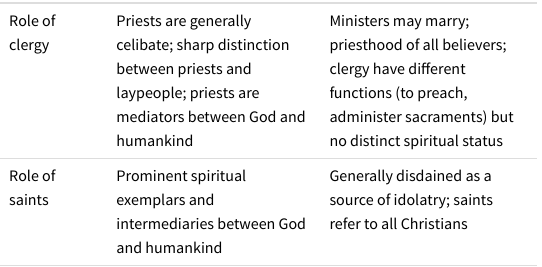

Differences in beliefs and practices:

<<QUESTION:<<

<<Using the information from this chart, what might be the causes for the appeal of Martin Luther’s ideas among many Europeans?( You better freaking do this or you will get a 45 on the test loser )<<

Contrary to Luther’s original intentions, his ideas provoked a massive ==schism== within the world of Catholic Christendom, for they came to express a variety of political, economic, and social tensions as well as religious differences. Some kings and princes, many of whom had long disputed the political authority of the pope, found in these ideas ==a justification for their own independence== and an ==opportunity to gain the lands and taxes== previously held by the Church. In the Protestant idea that all ==vocations== were of equal merit, middle-class urban dwellers found a new religious legitimacy for their growing role in society, since the Roman Catholic Church was associated in their eyes with the rural and feudal world of aristocratic privilege. For common people, who were offended by the corruption and luxurious living of some bishops, abbots, and popes, the new religious ideas served to express their opposition to the entire social order, particularly in a series of ==German peasant revolts in the 1520s.==

Women in the Protestant Reformation:

- Large numbers of women were attracted to Protestantism,

- Reformation teachings and practices did not offer them a substantially greater role in the Church or society.

- In Protestant-dominated areas, the veneration of Mary and female saints ended, leaving the male Christ figure as the sole object of worship.

- Protestant opposition to celibacy and monastic life closed the convents, which had offered some women an alternative to marriage.

- Nor were Protestants (except the ==Quakers==) any more willing than Catholics to offer women an official role within their churches.

- <<==The importance that Protestants gave to reading the Bible for oneself stimulated education and literacy for women, but given the emphasis on women as wives and mothers subject to male supervision, they had little opportunity to use that education outside of the family.==<<

Reformation thinking spread quickly both within and beyond Germany, thanks in large measure to the recent invention of the ==printing press==. Luther’s many pamphlets and his translation of the New Testament into German were soon widely available.

Thus to the sharp class divisions and the fractured political system of Europe was now added the potent brew of religious difference, operating both within and between states.

For more than thirty years (1562–1598), French society was torn by violence between Catholics and the Protestant minority known as ==Huguenots (HYOO-guh-naht)==. The culmination of European religious conflict took shape in the ==Thirty Year’s War (1618–1648)==.

Thirty Year’s War":

A Catholic–Protestant struggle that began in the Holy Roman Empire but eventually engulfed most of Europe. It was a horrendously destructive war, during which, scholars estimate, between 15 and 30 percent of the ==German population perished== from violence, famine, or disease. Finally, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) brought the conflict to an end, with some reshuffling of boundaries and an agreement that each state was sovereign, ==authorized to control religious affairs within its own territory==. Whatever religious unity Catholic Europe had once enjoyed was now permanently split.

The Protestant breakaway provoked a Catholic Reformation, or Counter Reformation. In the ==Council of Trent (1545–1563),== %%Catholics clarified%% and %%reaffirmed%% their ==unique doctrines, sacraments, and practices, such as the authority of the pope, priestly celibacy, the veneration of saints and relics, and the importance of church tradition and good works, all of which Protestants had rejected.== Moreover, they set about correcting the abuses and corruption that had stimulated the Protestant movement by placing a new emphasis on the education of priests and their supervision by bishops. Included the censorship of books, fines, exile, penitence, and sometimes the burning of heretics. New religious orders, such as the ==Society of Jesus (Jesuits)==, provided a dedicated brotherhood of priests committed to the renewal of the Catholic Church and its extension abroad.(Jehovah Witnesses)

Although the ==Reformation== was profoundly religious, it encouraged a skeptical attitude toward authority and tradition, for it had, after all, successfully challenged the immense prestige and power of the pope and the established Church. Protestant reformers ==fostered religious individualism==, as people now read and interpreted the scriptures for themselves and sought salvation without the mediation of the Church. In the centuries that followed, some people turned that skepticism and the habit of thinking independently against all conventional religion.

<<Thus the Protestant Reformation opened some space for new directions in European intellectual life.<<

Christianity Outward Bound:

Christianity motivated European political and economic expansion and also benefited from it. (like the Spaniards expanding to the Americas) When ==Vasco da Gama’s== small fleet landed in India in 1498, local authorities understandably asked, “What brought you hither?” The reply: they had come “in search of Christians and of spices.” ==No sense of any contradiction or hypocrisy== in this blending of religious and material concerns attended the reply.

If religion drove and justified European ventures abroad, it is difficult to imagine the globalization of Christianity without the support of empire. Colonial settlers and traders, of course, brought their faith with them and ==sought to replicate it== in their newly conquered homelands. New England Puritans planted a distinctive Protestant version of Christianity in North America, ==with an emphasis on education==, ==moral purity, personal conversion==, civic responsibility, and little tolerance for competing expressions of the faith. They did not show much interest in converting native peoples but sought rather to push them out of their territories. It was ==missionaries==, who actively spread the Christian message beyond European communities. Organized in missionary orders such as the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Jesuits, Portuguese missionaries took the lead in Africa and Asia, while Spanish and French missionaries were most prominent in the Americas. Missionaries of the Russian Orthodox Church likewise accompanied the expansion of the Russian Empire across Siberia, where priests and monks ministered to Russian settlers and trappers, who often donated their first sable furs to a church or monastery.

<<QUESTION:<<

<<How did European imperial expansion help spread Christianity? (Are you gonna answer this question?) (I think that you should or I am gonna send Mongols at you)<<

Missionaries:

Missionaries had their greatest success in Spanish America and in the Philippines. Most important, perhaps, was an overwhelming European presence, experienced variously as military conquest, colonial settlement, missionary activity, forced labor, social disruption, and disease. Surely it must have seemed as if the old gods had been bested and that any possible future lay with the powerful religion of the European invaders. A second common factor was the absence of a literate world religion in these two regions. Throughout the modern era, peoples solidly rooted in Confucian, Buddhist, Hindu, or Islamic traditions proved far more resistant to the Christian message than those who practiced more localized, small-scale, orally based religions. ==Spanish America and China illustrate the difference between those societies in which Christianity became widely practiced and those that largely rejected it.==

Conversion and Adaptation in Spanish America

Europeans saw their political and military success as a demonstration of the power of the Christian God. Native American peoples generally agreed, and the vast majority had been baptized and saw themselves as Christians. The Aztecs and the Incas had always imposed their ==gods== in some fashion on defeated peoples ( Comparison ). So it made sense to affiliate with the Europeans’ god. ==Many millions accepted baptism, contributed to the construction of village churches, attended services, and embraced images of saints==.

Women:

Despite the prominence of the Virgin Mary as a religious figure across Latin America, the cost of conversion was high, ==especially for women==. Many women who had long served as priests, shamans, or ritual specialists had ==no corresponding role in a Catholic church, led by an all-male clergy.== And, with a few exceptions, convent life, which had provided some outlet for female authority and education in Catholic Europe, was reserved largely for Spanish women in the Americas.

%%Earlier conquerors had made no attempt to eradicate local deities and religious practices%%. The flexibility of Mesoamerican and Andean religions had made it possible for people to follow the god==s== of their new rulers while ==maintaining their own traditions.== But Europeans were different. They claimed a religious truth and the utter destruction of gods and everything with them.

Comparison Summarization: Others would let people still believe and do some of their tradition but Europeans are wack and would kill you if you didn’t follow this one white dude.

At times, though, their frustration with the persistence of “idolatry, superstition, and error” boiled over into violent campaigns designed to uproot old religions once and for all. Church authorities in the Andean region periodically launched movements of ==“extirpation,”== designed to fatally undermine native religion. %%They destroyed religious images and ritual objects, publicly urinated on native “idols,” desecrated the remains of ancestors, flogged “idolaters,” and held religious trials and “processions of shame” aimed at humiliating offenders.%% It is hardly surprising that such aggressive action generated resistance. Writing around 1600, the native Peruvian nobleman Guaman Poma de Ayala commented on the posture of native women toward Christianity: “They do not confess; they do not attend catechism classes … nor do they go to mass…. And resuming their ancient customs and idolatry, they do not want to serve God or the crown.” Occasionally, overt resistance erupted. One such example was the religious revivalist movement in central Peru in the 1560s, known as %%Taki Onqoy (dancing sickness).%% Possessed by the %%spirits of local gods, or huacas, traveling dancers and teachers predicted that an alliance of Andean deities would soon overcome the Christian God,%% inflict the intruding Europeans with the same diseases that they had brought to the Americas, and restore the world of the Andes to an imagined earlier harmony. More common than such frontal attacks on Christianity, which colonial authorities quickly smashed, ==were efforts at blending two religious traditions, reinterpreting Christian practices within an Andean framework,== and incorporating local elements into an emerging Andean Christianity. Even female dancers in the Taki Onqoy took the names of Christian saints ( representation ) seeking to appropriate for themselves the religious power of Christian figures. ==Within Andean Christian communities, women might offer the blood of a llama to strengthen a village church or make a cloth covering for the Virgin Mary and a shirt for an image of a huaca with the same material.== Although the state cults of the Incas faded away, missionary attacks did not succeed in eliminating the influence of local huacas.

In Mexico as well, an immigrant Christianity was assimilated into patterns of local culture. Churches built near the sites of old temples became the focus of community identity. ^^Cofradias, church-based associations of laypeople,^^ organized community processions and festivals and made provisions for proper funerals and burials for their members. Central to an emerging Mexican Christianity were the saints who closely paralleled the functions of precolonial gods. Saints were imagined as parents of the local community and the true owners of its land. %%Mexico’s Virgin of Guadalupe neatly combined both Mesoamerican and Spanish notions of Divine Motherhood.%% Although parish priests were almost always Spanish, ^^the fiscal, or leader of the church staff, was a native Christian of great local prestige who carried on the traditions and role of earlier religious specialists^^. Many Mexican Christians also took part in rituals derived from the past, with little sense of incompatibility with Christian practice. Incantations to various gods for good fortune in hunting, farming, or healing; sacrifices of self-bleeding; offerings to the sun; divination; the use of hallucinogenic drugs — all of these practices provided spiritual assistance in those areas of everyday life not directly addressed by Christian rites. ^^Conversely, these practices also showed signs of Christian influence. Wax candles, normally used in Christian services, might now appear in front of a stone image of a precolonial god. The anger of a neglected saint, rather than that of a traditional god, might explain someone’s illness and require offerings, celebration, or a new covering to regain his or her favor. In such ways did Christianity take root in the new cultural environments of Spanish America, but it was a distinctly Andean or Mexican Christianity, not merely a copy of the Spanish version.^^ ( Rooting and christian influence )

An Asian Comparison: China and the Jesuits

The Chinese encounter with Christianity was very different from that of Native Americans in Spain’s New World empire. The most obvious difference was the political context. The peoples of Spanish America had been defeated, their societies thoroughly disrupted, and their cultural confidence sorely shaken. China, on the other hand, encountered European Christianity between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries during the powerful and prosperous Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties. ==At no point was China’s political independence or cultural integrity threatened by the handful of European missionaries and traders working there.==

==Europeans needed the permission of Chinese authorities to operate in the country.== ==Whereas Spanish missionaries working in a colonial setting sought primarily to convert the masses, the Jesuits in China the leading missionary order there, took deliberate aim at the official Chinese elite.== Many Jesuits learned Chinese, became thoroughly acquainted with classical Confucian texts, and dressed like Chinese scholars ( adapted to their society ). In presenting Christian teachings, Jesuits were at pains to be respectful of Chinese culture, ==pointing out parallels between Confucianism and Christianity rather than portraying Christianity as something new and foreign.== They chose to define Chinese rituals honoring the emperor or venerating ancestors as secular or civil observances rather than as religious practices that had to be abandoned( abided to them).

==Nothing approaching mass conversion to Christianity took place in China, as it had in Latin America.== A modest number of Chinese scholars and officials did become Christians, attracted by the personal lives of the missionaries, by their interest in Western science, and by the moral certainty that Christianity offered. Jesuit missionaries found favor for a time at the Chinese imperial court, where their mathematical, astronomical, technological, and mapmaking skills rendered them useful. ==For more than a century, they were appointed to head the Chinese Bureau of Astronomy.== Among poor people, Christianity spread very modestly amid tales of miracles attributed to the Christian God, while missionary teachings about ==“eternal life” sounded to some like Daoist prescriptions for immortality.==

The missionaries offered little that the Chinese really wanted. Confucianism for the elites and Buddhism, Daoism, and a multitude of Chinese gods and spirits at the local level adequately supplied the spiritual needs of most Chinese. Furthermore, it became increasingly clear that ==Christianity was an all-or-nothing faith that required converts to abandon much of traditional Chinese culture.== Christian monogamy, for example, seemed to require Chinese men to put away their concubines. What would happen to these deserted women?

<<The %%papacy%% and competing missionary orders came to oppose the Jesuit policy of accommodation. ==The pope claimed authority over Chinese Christians and declared that sacrifices to Confucius and the veneration of ancestors were “idolatry” and thus forbidden to Christians. The pope’s pronouncements represented an unacceptable challenge to the authority of the emperor and an affront to Chinese culture. In 1715, an outraged Emperor Kangxi prohibited Westerners from spreading Christian doctrine in his kingdom==. ==This represented a major turning point in the relationship between Christian missionaries and Chinese society. Many were subsequently expelled, and missionaries lost favor at court.==<<

Missionaries’ reputation as miracle workers further damaged their standing as men of science and rationality, ==for elite Chinese often regarded miracles and supernatural religion as superstitions, fit only for the uneducated masses.== Some viewed the Christian ritual of Holy Communion as a kind of %%cannibalism.%% Chinese notice that European Christians had taken over the Philippines and that their warships were active in the Indian Ocean. Perhaps the missionaries, with their great interest in maps, were spies for these aggressive foreigners. All of this contributed to the general failure of Christianity to secure a prominent presence in China.

Persistence and Change in Afro-Asian Cultural Traditions

Although Europeans were central players in the globalization of Christianity, theirs was not the only expanding or transformed culture of the early modern era. African religious ideas and practices, for example, accompanied slaves to the Americas. ==Common African forms of religious revelation — divination, dream interpretation, visions, spirit possession — found a place in the Africanized versions of Christianity that emerged in the New World.== Europeans frequently perceived these practices as evidence of sorcery, witchcraft, or even devil worship and tried to suppress them. %%Nonetheless, syncretic (blended) religions such as Vodou in Haiti, Santeria in Cuba, and Candomblé and Macumba in Brazil persisted%%. They derived from various West African traditions and featured drumming, ritual dancing, animal sacrifice, and spirit possession. Over time, they incorporated Christian beliefs and practices such as church attendance, the search for salvation, and the use of candles and crucifixes and often identified their various spirits or deities with Catholic saints( including aspects of Christianity ).

Expansion and Renewal in the Islamic World

The early modern era likewise witnessed the continuation of the %%“long march of Islam%%” across the Afro-Asian world. In sub-Saharan Africa, in the eastern and western wings of India, and in Central and Southeast Asia, the expansion of the Islamic frontier, a process already a thousand years in the making, extended farther still. %%Conversion to Islam generally did not mean a sudden abandonment of old religious practices in favor of the new. Rather, it was more often a matter of “%%==assimilating== %%Islamic rituals, cosmologies, and literatures into … local religious systems.%%

Continued Islamization was not usually the product of conquering armies and expanding empires. ==It depended instead on wandering Muslim holy men or Sufis, Islamic scholars, and itinerant traders, none of whom posed a threat to local rulers==. In fact, such people often were useful to those rulers and their village communities. They offered literacy in Arabic, established informal schools, provided protective charms containing passages from the Quran, served as advisers to local authorities and healers to the sick, often intermarried with local people, and generally did not insist that new converts give up their older practices. What they offered, in short, was connection to the wider, prestigious, prosperous world of Islam.

During the seventeenth century in ==Aceh, a Muslim sultanate on the northern tip of Sumatra==, authorities sought to enforce the dietary codes and almsgiving practices of Islamic law. @@After four successive women ruled the area in the late seventeenth century, women were forbidden from exercising political power.@@ @@On Muslim Java, however, numerous women served in royal courts, and women throughout Indonesia continued their longtime role as buyers and sellers in local markets.@@ Among ordinary Javanese, traditional animistic practices of spirit worship coexisted easily with a tolerant and accommodating Islam, while merchants often embraced a more orthodox version of the religion in line with Middle Eastern traditions.(Comparison)

@@To such orthodox Muslims, religious syncretism became increasingly offensive, even heretical.@@ The leaders of such movements sharply criticized those practices that departed from earlier patterns established by Muhammad and from the authority of the Quran. @@For example, in India, governed by the Muslim Mughal Empire, religious resistance to official policies that accommodated Hindus found concrete expression during the reign of the emperor Aurangzeb@@. A series of religious wars in West Africa during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries took aim at corrupt Islamic practices and the rulers, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, who permitted them. In Southeast and Central Asia, tension grew between practitioners of localized and blended versions of Islam and those who sought to purify such practices in the name of a more authentic and universal faith.( differing perspectives )

The Wahhabi movement:

The most well known and widely visible of these Islamic @@renewal movements@@ took place during the mid-eighteenth century @@in Arabia@@ itself, where they found expression in the teachings of the Islamic scholar Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792). The growing difficulties of the Islamic world, such as @@the weakening of the Ottoman Empire, were directly related,@@ he argued, to deviations from the pure faith of early Islam. Al-Wahhab was particularly upset by common religious practices in central Arabia that seemed to him idolatry — the widespread veneration of Sufi saints and their tombs, the adoration of natural sites, and even the respect paid to Muhammad’s tomb at Medina.

The Wahhabi movement took a new turn in the 1740s when it received the political backing of Muhammad Ibn Saud, a local ruler who found al-Wahhab’s ideas compelling. ( Cause ) With @@Ibn Saud’s support, the religious movement became an expansive state in central Arabia. Within that state, offending tombs were razed; “idols” were eliminated; books on logic were destroyed; the use of tobacco, hashish, and musical instruments was forbidden; and certain taxes not authorized by religious teaching were abolished.@@ ( Effect )

Although Wahhabi Islam has long been identified with sharp %%restrictions on women,%% Al-Wahhab himself generally emphasized the rights of women within a patriarchal Islamic framework.( contradicting ) %%These included the right to consent to and stipulate conditions for a marriage, to control her dowry, to divorce, and to engage in commerce%%. Furthermore, he did not insist on head-to-toe covering of women in public and allowed for the mixing of unrelated men and women for business or medical purposes.

By the early nineteenth century, this %%new reformist state%% (%%Wahhabi Islam) encompassed much of central Arabia,%% with Mecca itself coming under Wahhabi control in 1803 (see Map 7.3). Although an Egyptian army broke the power of the Wahhabis in 1818, the movement’s @@influence continued to spread@@ across the Islamic world. ^^Together with the ongoing expansion of the religion, these movements of reform and renewal signaled the continuing cultural vitality of the Islamic world even as the European presence on the world stage assumed larger dimensions.^^

China: New Directions in an Old Tradition

China and India emerged as commercial and urban life, as well as political change, fostered new thinking.

China during the Ming and Qing dynasties continued to operate a Confucian framework, enriched now by the insights of ^^Buddhism and Daoism to generate a system of thought called Neo-Confucianism^^.

During late Ming times, for example, the influential thinker Wang Yangming (1472–1529) argued that “intuitive moral knowledge exists in people … even robbers know that they should not rob.” Thus ^^anyone could achieve a virtuous life by introspection and contemplation, without the extended education, study of classical texts, and constant striving for improvement that traditional Confucianism prescribed for an elite class of “gentlemen.^^” prominently among Confucian scholars of the sixteenth century, although critics thought it promoted an excessive individualism. Some Chinese Buddhists as well sought to make their religion more accessible to ordinary people by suggesting that laypeople at home could undertake practices similar to those performed by monks in monasteries. Withdrawal from the world was not necessary for enlightenment. This kind of moral or religious individualism bore some similarity to the thinking of Martin Luther, who argued that individuals could seek salvation by “faith alone,” without the assistance of a priestly hierarchy.

^^Another new direction in Chinese elite culture took shape in a movement known as kaozheng, or “research based on evidence.” Intended to “seek truth from facts,” kaozheng was critical of the unfounded speculation of conventional Confucian philosophy and instead emphasized the importance of verification, precision, accuracy, and rigorous analysis in all fields of inquiry.^^ In the Qing era, kaozheng was associated with the recovery and critical analysis of ancient historical documents, which sometimes led to sharp criticism of Neo-Confucian orthodoxy.

India: Bridging the Hindu/Muslim Divide

In a largely Hindu India, ruled by the Muslim Mughal Empire, several significant cultural departures took shape in the early modern era that brought Hindus and Muslims together in new forms of religious expression. At the level of elite culture, the Mughal ruler ^^Akbar formulated a state cult that combined elements of Islam, Hinduism, and^^ @@Zoroastrianism@@ . Intended to bring this Hindu tradition into Islamic Sufi practice, the book, known as the @@Ocean of Life@@, portrayed some of the yogis in a Christ-like fashion.

Within popular culture, the flourishing of a devotional form of Hinduism known as @@bhakti also bridged the gulf separating Hindu and Muslim.@@ Through songs, prayers, dances, poetry, and rituals, devotees sought to achieve union with one or another of India’s many deities. Appealing especially to women, the bhakti movement provided an avenue for social criticism. Its practitioners often set aside caste distinctions and disregarded the detailed rituals of the Brahmin priests in favor of personal religious experience. The mystical dimension of the bhakti movement had much in common with Sufi forms of Islam, which also emphasized direct experience of the Divine. Such similarities helped blur the distinction between Hinduism and Islam in India, as both bhaktis and Sufis honored spiritual sages and all those seeking after God.

Among the most beloved of bhakti poets was Mirabai (1498–1547), a high-caste woman from northern India who abandoned her upper-class family and conventional Hindu practice. Upon her husband’s death, tradition asserts, she declined to burn herself on his funeral pyre (a practice known as sati ). She further offended caste restrictions by taking as her guru (religious teacher) an old untouchable shoemaker. To visit him, she apparently tied her saris together and climbed down the castle walls at night. Then she would wash his aged feet and drink the water from these ablutions. Much of her poetry deals with her yearning for union with Krishna, a Hindu deity she regarded as her husband, lover, and lord.

Yet another major cultural change that blended Islam and Hinduism emerged with the growth of Sikhism as a new and distinctive religious tradition in the Punjab region of northern India. Its founder, Guru Nanak (1469–1539), had been involved in the bhakti movement but came to believe that “there is no Hindu; there is no Muslim; only God.” His teachings and those of subsequent gurus also generally ignored caste distinctions and untouchability and ended the seclusion of women, while proclaiming the “brotherhood of all mankind” as well as the essential equality of men and women. Drawing converts from Punjabi peasants and merchants, both Muslim and Hindu, the Sikhs gradually became a separate religious community. They developed their own sacred book, known as the Guru Granth (teacher book); created a central place of worship and pilgrimage in the Golden Temple of Amritsar; and prescribed certain dress requirements for men, including keeping hair and beards uncut, wearing a turban, and carrying a short sword. During the seventeenth century, Sikhs encountered hostility from both the Mughal Empire and some of their Hindu neighbors. In response, Sikhism evolved from a peaceful religious movement, blending Hindu and Muslim elements, into a militant community whose military skills were highly valued by the British when they took over India in the late eighteenth century.

A New Way of Thinking: The Birth of Modern Science

While some Europeans were actively attempting to spread the Christian faith to distant corners of the world, others were nurturing an understanding of the cosmos at least partially at odds with traditional Christian teaching. These were the makers of Europe’s Scientific Revolution, a vast intellectual and cultural transformation that took place between the mid-sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries. These men of science no longer relied on the external authority of the Bible, the Church, the speculations of ancient philosophers, or the received wisdom of cultural tradition. For them, knowledge was acquired through rational inquiry based on evidence, the product of human minds alone. Those who created this revolution — Copernicus from Poland, Galileo from Italy, Descartes from France, Newton from England, and many others — saw themselves as departing radically from older ways of thinking. “The old rubbish must be thrown away,” wrote a seventeenth-century English scientist. “These are the days that must lay a new Foundation of a more magnificent Philosophy.”

The long-term significance of the Scientific Revolution can hardly be overestimated. Within early modern Europe, it fundamentally altered ideas about the place of humankind within the cosmos and sharply challenged both the teachings and the authority of the Church. Over the past several centuries, it has substantially eroded religious belief and practice in the West, particularly among the well educated. When applied to the affairs of human society, scientific ways of thinking challenged ancient social hierarchies and political systems and played a role in the revolutionary upheavals of the modern era. But science was also used to legitimize gender and racial inequalities, giving new support to old ideas about the natural inferiority of women and enslaved people. When married to the technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution, science fostered both the marvels of modern production and the horrors of modern means of destruction. By the twentieth century, science had become so widespread that it largely lost its association with European culture and became the chief marker of global modernity. Like Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, modern science became a universal worldview, open to all who could accept its premises and its techniques.

The Question of Origins: Why Europe?

Why did the breakthrough of the Scientific Revolution occur first in Europe and during the early modern era? The realm of Islam, after all, had generated the most advanced science in the world during the centuries between 800 and 1400. Arab scholars could boast of remarkable achievements in mathematics, astronomy, optics, and medicine, and their libraries far exceeded those of Europe. And China’s elite culture of Confucianism was both sophisticated and secular, less burdened by religious dogma than that of the Christian or Islamic worlds; its technological accomplishments and economic growth were unmatched anywhere in the several centuries after 1000. In neither civilization, however, did these achievements lead to the kind of intellectual innovation that occurred in Europe.

Europe’s historical development as a reinvigorated and fragmented civilization arguably gave rise to conditions particularly favorable to the scientific enterprise. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Europeans had evolved a legal system that guaranteed a measure of independence for a variety of institutions — the Church, towns and cities, guilds, professional associations, and universities. This legal revolution was based on the idea of a “corporation,” a collective group of people that was treated as a unit, a legal person, with certain rights to regulate and control its own members.

Most important for the development of science in the West was the autonomy of its emerging universities. By 1215, the University of Paris was recognized as a “corporation of masters and scholars,” which could admit and expel students, establish courses of instruction, and grant a “license to teach” to its faculty. Such universities — for example, in Paris, Bologna, Oxford, Cambridge, and Salamanca — became “neutral zones of intellectual autonomy” in which scholars could pursue their studies in relative freedom from the dictates of church or state authorities. Within them, the study of the natural order began to slowly separate itself from philosophy and theology and to gain a distinct identity. Their curricula featured “a core of readings and lectures that were basically scientific,” drawing heavily on the writings of the Greek thinker Aristotle, which had only recently become available to Western Europeans. Most of the major figures in the Scientific Revolution had been trained in and were affiliated with these universities.

By contrast, in Islamic colleges known as madrassas, Quranic studies and religious law held the central place, whereas philosophy and natural science were viewed with considerable suspicion. To religious scholars, the Quran held all wisdom, and scientific thinking might well challenge it. An earlier openness to free inquiry and religious toleration was increasingly replaced by a disdain for scientific and philosophical inquiry, for it seemed to lead only to uncertainty and confusion. “May God protect us from useless knowledge” was a saying that reflected this outlook. Nor did Chinese authorities permit independent institutions of higher learning in which scholars could conduct their studies in relative freedom. Instead, Chinese education focused on preparing for a rigidly defined set of civil service examinations and emphasized the humanistic and moral texts of classical Confucianism. “The pursuit of scientific subjects,” one recent historian concluded, “was thereby relegated to the margins of Chinese society.”

Beyond its distinctive institutional development, Western Europe was in a position to draw extensively on the knowledge of other cultures, especially that of the Islamic world. Arab medical texts, astronomical research, and translations of Greek classics played a major role in the birth of European natural philosophy (as science was then called) between 1000 and 1500. Then, in the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, Europeans found themselves at the center of a massive new exchange of information as they became aware of lands, peoples, plants, animals, societies, and religions from around the world. This tidal wave of new knowledge, uniquely available to Europeans, shook up older ways of thinking and opened the way to new conceptions of the world. The sixteenth-century Italian doctor, mathematician, and writer Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576) clearly expressed this sense of wonderment: “The most unusual [circumstance of my life] is that I was born in this century in which the whole world became known; whereas the ancients were familiar with but a little more than a third part of it.” He worried, however, that amid this explosion of knowledge, “certainties will be exchanged for uncertainties.” It was precisely those uncertainties — skepticism about established views — that provided such a fertile cultural ground for the emergence of modern science. The Reformation too contributed to that cultural climate in its challenge to authority, its encouragement of mass literacy, and its affirmation of secular professions.

Science as Cultural Revolution

Before the Scientific Revolution, educated Europeans held to an ancient view of the world in which the earth was stationary and at the center of the universe, and around it revolved the sun, moon, and stars embedded in ten spheres of transparent crystal. This understanding coincided well with the religious outlook of the Catholic Church because the attention of the entire universe was centered on the earth and its human inhabitants, among whom God’s plan for salvation unfolded. It was a universe of divine purpose, with angels guiding the hierarchically arranged heavenly bodies along their way while God watched over the whole from his realm beyond the spheres. The Scientific Revolution was revolutionary because it fundamentally challenged this understanding of the universe.

The initial breakthrough in the Scientific Revolution came from the Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, whose famous book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres was published in the year of his death, 1543. Its essential argument was that “at the middle of all things lies the sun” and that the earth, like the other planets, revolved around it. Thus the earth was no longer unique or at the obvious center of God’s attention.

Other European scientists built on Copernicus’s central insight. In the early seventeenth century Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician, showed that the planets followed elliptical orbits, undermining the ancient belief that they moved in perfect circles. In 1609 the Italian Galileo (gal-uh-LAY-oh) developed an improved telescope, with which he made many observations that undermined established understandings of the cosmos. (See Zooming In: Galileo and the Telescope.) Some thinkers began to discuss the notion of an unlimited universe in which humankind occupied a mere speck of dust in an unimaginable vastness. The seventeenth-century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal perhaps spoke for many when he wrote, “The eternal silence of infinite space frightens me.”15

The culmination of the Scientific Revolution came in the work of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), the Englishman who formulated the modern laws of motion and mechanics, which remained unchallenged until the twentieth century. At the core of Newton’s thinking was the concept of universal gravitation. “All bodies whatsoever,” Newton declared, “are endowed with a principle of mutual gravitation.”16 Here was the grand unifying idea of early modern science. The radical implication of this view was that the heavens and the earth, long regarded as separate and distinct spheres, were not so different after all, for the motion of a cannonball or the falling of an apple obeyed the same natural laws that governed the orbiting planets.

By the time Newton died, a revolutionary new understanding of the physical universe had emerged among educated Europeans: the universe was no longer propelled by supernatural forces but functioned on its own according to scientific principles that could be described mathematically. Articulating this view, Kepler wrote, “The machine of the universe is not similar to a divine animated being but similar to a clock.”18 Furthermore, it was a machine that regulated itself, requiring neither God nor angels to account for its normal operation. Knowledge of that universe could be obtained through human reason alone — by observation, deduction, and experimentation — without the aid of ancient authorities or divine revelation. The French philosopher René Descartes (day-KAHRT) resolved “to seek no other knowledge than that which I might find within myself, or perhaps in the book of nature.”

Like the physical universe, the human body also lost some of its mystery. The careful dissections of cadavers and animals enabled doctors and scientists to describe the human body with much greater accuracy and to understand the circulation of the blood throughout the body. The heart was no longer the mysterious center of the body’s heat and the seat of its passions; instead it was just another machine, a complex muscle that functioned as a pump.

The movers and shakers of this enormous cultural transformation were almost entirely male. European women, after all, had been largely excluded from the universities where much of the new science was discussed. A few aristocratic women, however, had the leisure and connections to participate informally in the scientific networks of their male relatives. Through her marriage to the Duke of Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673) joined in conversations with a circle of “natural philosophers,” wrote six scientific texts, and was the only seventeenth-century Englishwoman to attend a session of the Royal Society of London, created to foster scientific learning. In Germany, a number of women took part in astronomical work as assistants to their husbands or brothers. Maria Winkelmann, for example, discovered a previously unknown comet, though her husband took credit for it. After his death, she sought to continue his work in the Berlin Academy of Sciences but was refused on the grounds that “mouths would gape” if a woman held such a position.

Much of this scientific thinking developed in the face of strenuous opposition from the Catholic Church, for both its teachings and its authority were under attack. The Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, proclaiming an infinite universe and many worlds, was burned at the stake in 1600, and Galileo was compelled by the Church to publicly renounce his belief that the earth moved around an orbit and rotated on its axis.

But scholars have sometimes exaggerated the conflict of science and religion, casting it in military terms as an almost unbroken war. None of the early scientists, however, rejected Christianity. Copernicus, in fact, published his famous book with the support of several leading Catholic churchmen and dedicated it to the pope. Galileo himself proclaimed the compatibility of science and faith, and his lack of diplomacy in dealing with church leaders was at least in part responsible for his quarrel with the Church.23 Newton was a serious biblical scholar and saw no inherent contradiction between his ideas and belief in God. “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets,” he declared, “could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent Being.”24 In such ways the scientists sought to accommodate religion. Over time, scientists and Church leaders learned to coexist through a kind of compartmentalization. Science might prevail in its limited sphere of describing the physical universe, but religion was still the arbiter of truth about those ultimate questions concerning human salvation, righteous behavior, and the larger purposes of life.

Science and Enlightenment

Initially limited to a small handful of scholars, the ideas of the Scientific Revolution spread to a wider European public during the eighteenth century, aided by novel techniques of printing and bookmaking, by a popular press, by growing literacy, and by a host of scientific societies. Moreover, the new approach to knowledge — rooted in human reason, skeptical of authority, expressed in natural laws — was now applied to human affairs, not just to the physical universe. The Scottish professor Adam Smith (1723–1790), for example, formulated laws that accounted for the operation of the economy and that, if followed, he believed, would generate inevitably favorable results for society. Growing numbers of people believed that the long-term outcome of scientific development would be “enlightenment,” a term that has come to define the eighteenth century in European history. If human reason could discover the laws that governed the universe, surely it could uncover ways in which humankind might govern itself more effectively.

“What is Enlightenment?” asked the prominent German intellectual Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). “It is man’s emergence from his self-imposed … inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance…. Dare to know! ‘Have the courage to use your own understanding’ is therefore the motto of the enlightenment.”25 Although they often disagreed sharply with one another, European Enlightenment thinkers shared this belief in the power of knowledge to transform human society. They also shared a satirical, critical style, a commitment to open-mindedness and inquiry, and in various degrees a hostility to established political and religious authority. Many took aim at arbitrary governments, the “divine right of kings,” and the aristocratic privileges of European society. The English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) offered principles for constructing a constitutional government, a contract between rulers and ruled that was created by human ingenuity rather than divinely prescribed. Much of Enlightenment thinking was directed against the superstition, ignorance, and corruption of established religion. In his Treatise on Toleration, the French writer Voltaire (1694–1778) reflected the outlook of the Scientific Revolution as he commented sarcastically on religious intolerance:

Voltaire’s own faith, like that of many others among the “enlightened,” was deism. Deists believed in a rather abstract and remote Deity, sometimes compared to a clockmaker, who had created the world, but not in a personal God who intervened in history or tampered with natural law. Others became pantheists, who believed that God and nature were identical. Here were conceptions of religion shaped by the outlook of science. Sometimes called “natural religion,” it was devoid of mystery, revelation, ritual, and spiritual practice, while proclaiming a God that could be “proven” by human rationality, logic, and the techniques of scientific inquiry. In this view, all else was superstition. Among the most radical of such thinkers were the several Dutchmen who wrote the Treatise of Three Imposters, which claimed that Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad were fraudulent deceivers who based their teachings on “the ignorance of Peoples [and] resolved to keep them in it.”

Prominent among the debates spawned by the Enlightenment was the question of women’s nature, their role in society, and the education most appropriate for them. Although well-to-do Parisian women hosted in their elegant salons many gatherings of the largely male Enlightenment figures, most of those men were anything but ardent feminists. The male editors of the famous Encyclopédie, a vast compendium of Enlightenment thought, included very few essays by women. One of the male authors expressed a common view: “[Women] constitute the principal ornament of the world…. May they, through submissive discretion and … artless cleverness, spur us [men] on to virtue.” In his treatise Emile, Jean-Jacques Rousseau described women as fundamentally different from and inferior to men and urged that “the whole education of women ought to be relative to men.”

Such views were sharply contested by any number of other Enlightenment figures — men and women alike. The Journal des Dames (Ladies Journal), founded in Paris in 1759, aggressively defended women. “If we have not been raised up in the sciences as you have,” declared Madame Beaulmer, the Journal’s first editor, “it is you [men] who are the guilty ones; for have you not always abused … the bodily strength that nature has given you?”28 The philosopher Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794) looked forward to the “complete destruction of those prejudices that have established an inequality of rights between the sexes.” And in 1792, the British writer Mary Wollstonecraft directly confronted Rousseau’s view of women and their education: “What nonsense! … Til women are more rationally educated, the progress of human virtue and improvement in knowledge must receive continual checks.” Thus was initiated a debate that echoed throughout the centuries that followed.

Though solidly rooted in Europe, Enlightenment thought was influenced by the growing global awareness of its major thinkers. Voltaire, for example, idealized China as an empire governed by an elite of secular scholars selected for their talent, which stood in sharp contrast to continental Europe, where aristocratic birth and military prowess were far more important. The example of Confucianism — supposedly secular, moral, rational, and tolerant — encouraged Enlightenment thinkers to imagine a future for European civilization without the kind of supernatural religion that they found so offensive in the Christian West.

The central theme of the Enlightenment — and what made it potentially revolutionary — was the idea of progress. Human society was not fixed by tradition or divine command but could be changed, and improved, by human action guided by reason. No one expressed this soaring confidence in human possibility more clearly than the French thinker Condorcet, who boldly declared that “the perfectibility of humanity is indefinite.” Belief in progress was a sharp departure from much of premodern social thinking, and it inspired those who later made the great revolutions of the modern era in the Americas, France, Russia, China, and elsewhere. Born of the Scientific Revolution, that was the faith of the Enlightenment. For some, it was virtually a new religion.

The age of the Enlightenment, however, also witnessed a reaction against too much reliance on human reason. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) minimized the importance of book learning for the education of children and prescribed instead an immersion in nature, which taught self-reliance and generosity rather than the greed and envy fostered by “civilization.” The Romantic movement in art and literature appealed to emotion, intuition, passion, and imagination rather than cold reason and scientific learning. Religious awakenings — complete with fiery sermons, public repentance, and intense personal experience of sin and redemption — shook Protestant Europe and North America in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Methodist movement — with its emphasis on Bible study, confession of sins, fasting, enthusiastic preaching, and resistance to worldly pleasures — was a case in point.

Various forms of “enlightened religion” also arose in the early modern centuries, reflecting the influence of Enlightenment thinking. Quakers, for example, emphasized tolerance, an absence of hierarchy and ostentation, a benevolent God, and an “inner light” available to all people. Unitarians denied the Trinity, original sin, predestination, and the divinity of Jesus, but honored him as a great teacher and a moral prophet. Later, in the nineteenth century, proponents of the “social gospel” saw the essence of Christianity not in personal salvation but in ethical behavior. Science and the Enlightenment surely challenged religion, and for some they eroded religious belief and practice. Just as surely, though, religion persisted, adapted, and revived for many others.

European Science beyond the West

In the long run, the achievements of the Scientific Revolution spread globally, becoming the most widely sought-after product of European culture and far more desired than Christianity, democracy, socialism, or Western literature. In the early modern era, however, interest in European scientific thinking within major Asian societies was both modest and selective. The telescope provides an example. Invented in early seventeenth-century Europe and endlessly improved in the centuries that followed, the telescope provoked enormous excitement in European scientific circles. “We are here … on fire with these things,” wrote an English astronomer in 1610.29 Soon the telescope was available in China, Mughal India, and the Ottoman Empire. But in none of these places did it evoke much interest or evolve into the kind of “discovery machine” that it was rapidly becoming in Europe.

In China, Qing dynasty emperors and scholars were most interested in European techniques for predicting eclipses, reforming the calendar, and making accurate maps of the empire. European mathematics was also of particular interest to Chinese scholars who were exploring the history of Chinese mathematics. To convince their skeptical colleagues that the barbarian Europeans had something to offer in this field, some Chinese scholars argued that European mathematics had in fact grown out of much earlier Chinese ideas and could therefore be adopted with comfort.30 European medicine, however, was of little importance for Chinese physicians before the nineteenth century. In such ways, early modern Chinese thinkers selectively assimilated Western science very much on their own terms.

Although Japanese authorities largely closed their country off from the West in the early seventeenth century (see Chapter 6), one window remained open. Alone among Europeans, the Dutch were permitted to trade in Japan at a single location near Nagasaki, but not until 1720 did the Japanese lift the ban on importing Western books. Then a number of European texts in medicine, astronomy, geography, mathematics, and other disciplines were translated and studied by a small group of Japanese scholars. They were especially impressed with Western anatomical studies, for in Japan dissection was work fit only for outcasts. Returning from an autopsy conducted by Dutch physicians in the mid-eighteenth century, several Japanese observers reflected on their experience: “We remarked to each other how amazing the autopsy had been, and how inexcusable it had been for us to be ignorant of the anatomical structure of the human body.”32 Nonetheless, this small center of “Dutch learning,” as it was called, remained isolated amid a pervasive Confucian-based culture. Not until the mid-nineteenth century, when Japan was forcibly opened to Western penetration, would European-style science assume a prominent place in Japanese culture.

Like China and Japan, the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was an independent, powerful, successful society whose intellectual elites saw no need for a wholesale embrace of things European. Ottoman scholars were conscious of the rich tradition of Muslim astronomy and chose not to translate the works of major European scientists such as Copernicus, Kepler, or Newton, although they were broadly aware of European scientific achievements by 1650. Insofar as they were interested in these developments, it was for their practical usefulness in making maps and calendars rather than for their larger philosophical implications. In any event, the notion of a sun-centered solar system did not cause the kind of upset that it did in Europe.

More broadly, theoretical science of any kind — Muslim or European — faced an uphill struggle in the face of a conservative Islamic educational system. In 1580, for example, a highly sophisticated astronomical observatory in Constantinople was dismantled under pressure from conservative religious scholars and teachers, who interpreted an outbreak of the plague as God’s disapproval of those who sought to understand his secrets. As in Japan, the systematic embrace of Western science would have to await the nineteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire was under far more intense European pressure and reform seemed more necessary.

Looking Ahead: Science in the Nineteenth Century and Beyond

In Europe itself, the impetus of the Scientific Revolution continued to unfold. Modern science, it turned out, was a cumulative and self-critical enterprise, which in the nineteenth century and later was applied to new domains of human inquiry in ways that undermined some of the assumptions of the Enlightenment. This remarkable phenomenon justifies a brief look ahead at several scientific developments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In the realm of biology, for example, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) laid out a complex argument that all life was in constant change, that an endless and competitive struggle for survival over millions of years constantly generated new species of plants and animals, while casting others into extinction. Human beings were not excluded from this vast process, for they too were the work of evolution operating through natural selection. Darwin’s famous books The Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871) were threatening to many traditional Christian believers, perhaps more so than Copernicus’s ideas about a sun-centered universe had been several centuries earlier.

At the same time, Karl Marx (1818–1883) articulated a view of human history that likewise emphasized change and struggle. Conflicting social classes — slave owners and slaves, nobles and peasants, capitalists and workers — successively drove the process of historical transformation. Although he was describing the evolution of human civilization, Marx saw himself as a scientist. He based his theories on extensive historical research; like Newton and Darwin, he sought to formulate general laws that would explain events in a rational way. Nor did he believe in heavenly intervention, chance, or the divinely endowed powers of kings. In Marx’s view the coming of socialism — a society without classes or class conflict — was not simply a good idea; it was inevitable, inscribed in the laws of historical development. (See “Social Protest” in Chapter 9.) Like the intellectuals of the Enlightenment, Darwin and Marx believed strongly in progress, but in their thinking, conflict and struggle rather than reason and education were the motors of progress. The Enlightenment image of the thoughtful, rational, and independent individual was fading. Individuals — plant, animal, and human alike — were now viewed as enmeshed in vast systems of biological, economic, or social conflict.

The work of the Viennese doctor Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) applied scientific techniques to the operation of the human mind and emotions and in doing so cast further doubt on Enlightenment conceptions of human rationality. At the core of each person, Freud argued, lay primal impulses toward sexuality and aggression, which were only barely held in check by the thin veneer of social conscience derived from civilization. Our neuroses arose from the ceaseless struggle between our irrational drives and the claims of conscience and society. This too was a far cry from the Enlightenment conception of the human condition.

And in the twentieth century, developments in physics, such as relativity and quantum theory, called into question some of the established verities of the Newtonian view of the world, particularly at the subatomic level and at speeds approaching that of light. In this new physics, time is relative to the position of the observer; space can warp and light can bend; matter and energy are equivalent; black holes and dark matter abound; and probability, not certain prediction, is the best that scientists can hope for. None of this was even on the horizon of those who made the original Scientific Revolution in the early modern era.

Unknown words:

- Schism - Permanent split ( never going back together )

- Vocations -

- ==extirpation -==