Evaluating Sources - Rhetoric

Evaluating a Source's Rhetoric

In the last lesson, we discussed the importance of identifying a source's purpose, whether to persuade, inform, or entertain. Since you are writing a research paper, your work and the works you will read will mostly be persuasive in intent. You will need to learn to identify persuasive appeals and rhetorical devices.

As we learn about these specific types of persuasion, remember that persuasion is a healthy, normal part of human interaction. We persuade each other every day, multiple times a day, in big and small ways. However, as with anything, persuasion is often abused. In this lesson, we will identify when healthy persuasion becomes unhealthy manipulation. We will identify when rhetorical devices are used to mask or distract from the truth.

Persuasive Appeals

God created us in His image, with faculties that reflect Him. He created all aspects we share as humans, and they point back to Him. Our intellects—or our minds—reflect the created order in the universe; our emotions reflect his love and care for his creation; and our souls, or spirits, which will live forever, reflect the immortality of God—the fact that he has always existed and always will. Our mind, emotions, and spirit are part of our being made "in the image of God."

Thus, when we persuade and are persuaded by others, we make appeals (or petitions) that engage human reason, emotions, and character: Aristotle called these appeals logos, pathos, and ethos.

Logos (Appeal to Mind)

Logos (Greek for "word") is used as an appeal to our intellect. When a source wants to persuade the reader's mind, it provides indisputable facts, figures, and reasons supporting its claim.

This is the most common appeal in nonfiction sources like scholarly journals or books, which usually provide complete bibliographies and/or footnotes. Scholarly journals and books painstakingly build persuasive arguments by stacking up example on top of example, reason on top of reason, and fact on top of fact.

When you begin to work on your research paper next week, we will stress the importance of proving your points with data and logic. The sources you choose, therefore, should also be filled with true facts and clear information.

Read through this short editorial from The New York Times Upfront and look for the use of logos.

"Are Pro Athletes Overpaid?"

The New York Times Upfront

CLICK HERE(OPENS IN A NEW TAB)

This article compared two opposing answers to the question, "are pro athletes overpaid?" Both perspectives rely on logos to persuade the reader.

Both perspectives provide facts and figures to support their claim. For example, the "yes" perspective compares the average salary of an athlete with the average salaries of firefighters, schoolteachers, and nurses; his logical claim is that these salaries don't match up with the sacrifices they make.

Both perspectives use logic and reason to support their claim. Here is an example from the "no" perspective:

"The truth is, some professional athletes make huge salaries because millions of people are happy to pay money to see those players make the amazing catches and breathtaking plays we love to watch" (Spector).

The logic is simple: pro athletes are paid highly because they please so many people.The "no" perspective opens with a counterclaim:

"When fans look at professional athletes' salaries, it's easy to say they make far too much money for playing a game. After all, athletes earn more money than teachers, first responders, and members of the military. More than half the people in the United States make less than $62,000 a year" (Bowen).

This is a very effective rhetorical strategy: by using a counterclaim, the author assures the reader's mind that he is fully aware of and unshaken by the arguments against his claim.

This editorial provides two positive examples of logos in a source. Both perspectives offer accurate information and fair logic, even if some readers disagree with the conclusions.

However, logos can easily be abused when authors attempt to persuade the audience to believe false or biased information.

Misinformation can spread incredibly quickly on the internet. For example:

Out-of-context quotations

Skewed statistics

"Fake news"

Biased recounting of events

A major part of media literacy is checking the sources whenever and wherever an information claim is made.

Another abuse of logos is called card stacking. Card stacking occurs when the writer/speaker gives information and evidence selectively. This means they present only the information that supports their opinion and conveniently leave out any evidence that contradicts it.

This advertisement for Burger King fries stacks a lot of positive-sounding facts and figures: the fries have less fat, fewer calories, and are made from "real, whole potatoes." The ad conveniently leaves out how much fat and calories are still in the fries! It doesn't mention that they are fried in fat and covered in salt. By using some facts and leaving out others (card stacking), the ad abuses its appeal to logic.

Pathos (Appeal to Heart)

Pathos (Greek for "experience") appeals to the universal emotions and connections humans have shared throughout all time. When a source uses pathos, it attempts to convince the heart of the truth of a claim.

We, humans, are thinking beings, but we are also emotional beings. We strongly connect to or reject things based on our gut feelings. This is why parents choose schools where they believe their children will be safe and happy. This is why we watch movies with our favorite celebrities. This is why we angrily sign online petitions against social injustice.

Believe it or not, emotional persuasion can be used well in nonfiction. Some nonfiction uses our concern for others to remind us to take action.

Below is an excerpt from the famous Gettysburg Address. President Lincoln delivered this speech in November 1863 to honor the bloody Battle of Gettysburg.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln, Abraham. "The Gettysburg Address." 1863. National Geographic Society, 13 Mar. 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/gettysburg-address/.

Lincoln appeals to his listeners' emotions by reminding them how many men sacrificed their lives. He appeals to values like patriotism, camaraderie, and freedom to persuade his listeners that they must carry on the fight.

You may be using one or more of the literary works we read in this course for your senior research paper. Fictional works, like novels and plays, often use pathos to impress a theme or message on the reader.

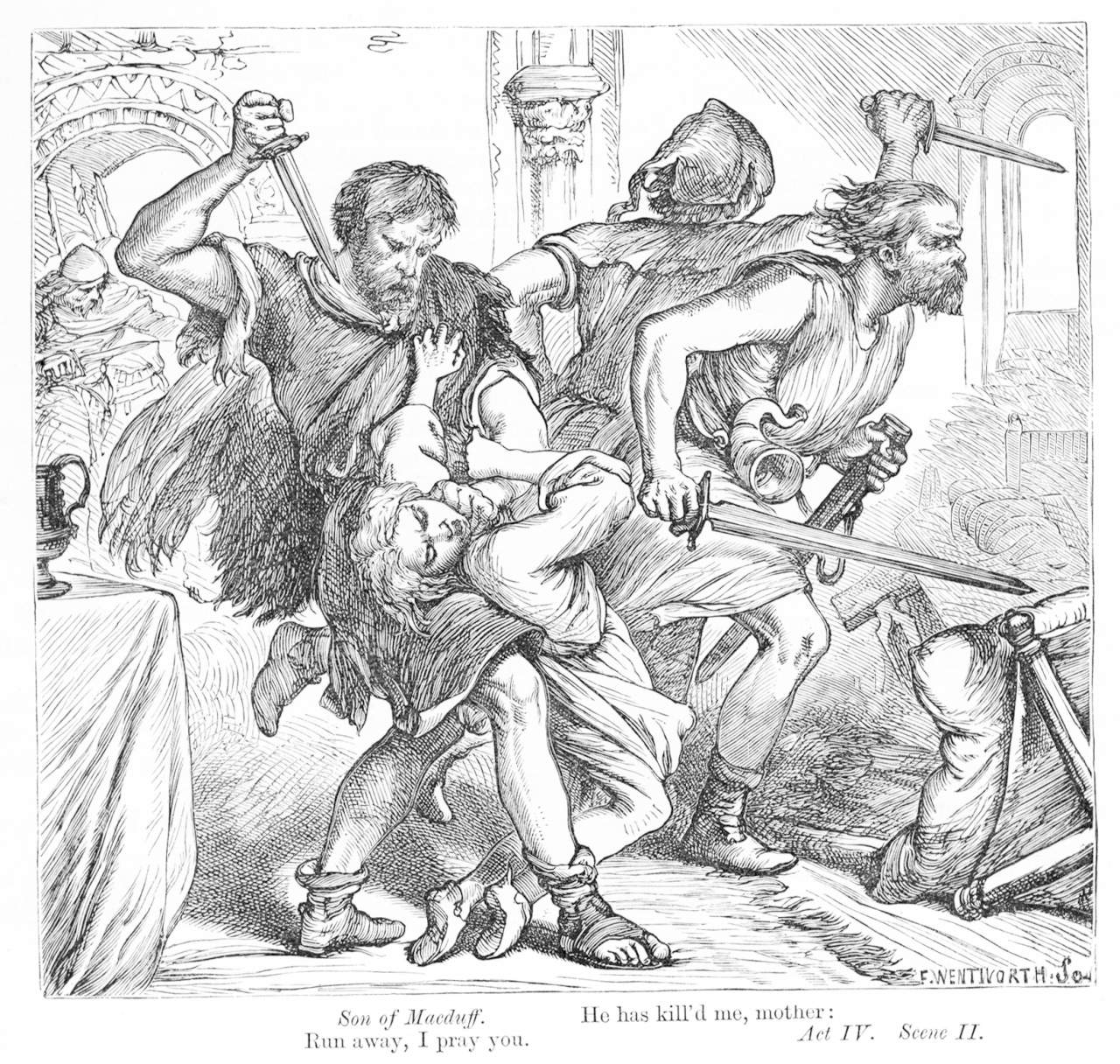

For example, one of the main themes in Macbeth is the cost of tyranny. To emphasize this point, Shakespeare appeals to the heart by depicting the murder of Macduff's innocent wife and son. He appeals to our cultural values of family and peace by depicting the breaking of these values. During this scene, the readers/viewers experience and feel the horror and fear of a bloody tyrant.

As you can probably guess, it is very easy to abuse emotional persuasion. Websites, newspapers, and magazines often publish emotionally-driven articles to get more "clicks." For example,

"Are Cellphones Ruining Your Connection with Your Kids?"

"Eating Canned Foods Gives You Cancer"

"10 Ways to Get Your Friends to Like You More"

Each of these titles abuses our emotions, causing us to fear the loss of love, health, or friendship. On the internet, avoid articles written to sell to, anger, or frighten the reader rather than share unbiased information.

Abuse of emotional persuasion can create widespread panic on social media. Posts like this, which provide no research, are the culprit:

Ethos (Appeal to Character)

Ethos (Greek for "character") appeals to an author's authority, expertise, and/or character. The appeal links an idea/thing to a person whom the reader can trust. Ethos seeks to convince the reader of something by connecting that thing to another person's trustworthiness.

In everyday life, we tend to look for authorities on various topics to help us make decisions. As you entered high school, you may have asked an older student or sibling to tell you what it would be like, simply because they were experts in that area. We trust doctors to help us with our health because they have medical degrees.

Good examples of persuasion by association abound in nonfiction. Journal articles, books, and scholarly essays are written by verified experts who quote other experts.

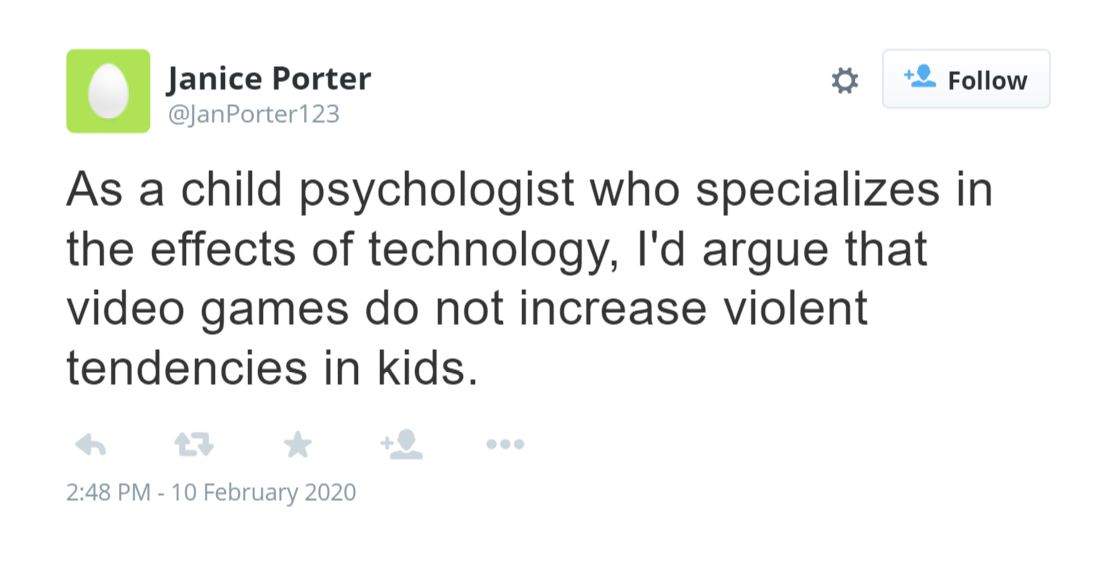

In online articles, speeches, and social media posts, speakers may refer to their expertise (or personal experience) with a topic to persuade their audience to believe and agree with them. Writers often use the phrase "as a ..." before beginning their argument. They want to tell their audience they know what they're talking about.

This is valid, persuasive reasoning in Janice's favor! She shows she has enough knowledge of the topic to disagree with anti-video game posters.

By contrast, there are two main ways that persuasion by association can be abused:

Do not be persuaded by a writer who claims that what they say is true only because they have experience or expertise. Even experts can be wrong or manipulative; good experts, therefore, will provide evidence and other sources to support their argument.

Be aware of expert/authority switching: an authority on one subject speaks confidently (often falsely) on a different subject. This happens more often than we realize! Examples include physicists speaking about evolutionary biology, literary critics speaking about history, and actors/singers speaking about politics.

A Note about Persuasive Language

Word choices can be incredibly persuasive. One word can change our perspective on an idea or claim. Consider the difference between:

This man keeps a lot of money.

This frugal man saves a lot of money.

This greedy man hoards a lot of money.

To further illustrate this, here is an excerpt from a recent editorial in Atlantic, "How AI Will Rewire Us":

As digital assistants become ubiquitous, we are becoming accustomed to talking to them as though they were sentient; writing in these pages last year, Judith Shulevitz described how some of us are starting to treat them as confidants, or even as friends and therapists. Shulevitz herself says she confesses things to Google Assistant that she wouldn't tell her husband. If we grow more comfortable talking intimately to our devices, what happens to our human marriages and friendships? Thanks to commercial imperatives, designers and programmers typically create devices whose responses make us feel better—but may not help us be self-reflective or contemplate painful truths. As AI permeates our lives, we must confront the possibility that it will stunt our emotions and inhibit deep human connections, leaving our relationships with one another less reciprocal, or shallower, or more narcissistic.

"How AI Will Rewire Us"

All of the highlighted words work together to persuade the reader that AI is too close to us and too involved in our everyday lives. But switch these words out—maybe "abundant" instead of "ubiquitous"—and the piece might not get that particular message across.

Take care that you refrain from manipulating the reader of your research paper with word choices. Always pair persuasive language with objective logic and sources.

Knowt

Knowt