Summary_Psychodiagnostics_GGZ2030.docx

Summary Psychodiagnostics GGZ2030

Psychological test = a standardised measure of a sample of behaviour that establishes norms and uses important test items that correspond to what the test is to discover about the test-taker. Is also based on uniformity of procedures in administering and scoring tests.

The standardised measure of a sample of behaviour = an established reference point that a test scorer can use to evaluate, judge, measure against, and compare.

Test items = the questions that a test-taker is asked on any given test.

Uniformity of procedures in administering and scoring of tests = refers to administrators presenting the test in the same way, test-takers taking the test in the same way, and scorers scoring the test the same way every given time that this test is given, taken, and scored 🡪 this helps with:

Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be reproducible but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be reproducible. |

Some of the primary purposes of psychological assessment are to:

disturbance, and capacity for independent living.

recommend forms of intervention and offer guidance about likely outcomes.

identify new issues that may require attention as original concerns are

resolved.

identification of untoward treatment reactions.

in itself.

Although specific rules cannot be developed, provisional guidelines for when assessments are likely to have the greatest utility in general clinical practice can be offered.

3 readily accessible but inappropriate benchmarks can lead to unrealistically high expectations about effect magnitudes:

Instead of relying on unrealistic benchmarks to evaluate findings 🡪 psychologists should be satisfied when they can identify replicated univariate correlations among independently measured constructs.

Therapeutic impact is likely to be greatest when:

Monomethod validity coefficients = are obtained whenever numerical values on a predictor and criterion are completely or largely derived from the same source of information.

Distinctions between psychological testing and psychological assessment:

Distinctions between formal assessment and other sources of clinical information:

Assessment methods:

Clinicians and researchers should recognize the unique strengths and limitations of various assessment methods and harness these qualities to select methods that help them more fully understand the complexity of the individual being evaluated.

Low cross-method correspondence can indicate problems with one or both methods. Cross-method correlations cannot reveal what makes a test distinctive or unique, and they also cannot reveal how good a test is in any specific sense.

Clinicians must not rely on 1 method.

One cannot derive unequivocal clinical conclusions from test scores considered in isolation.

Because most research studies do not use the same type of data that clinicians do when performing an individualised assessment, the validity coefficients from testing research may underestimate the validity of test findings when they are integrated into a systematic and individualised psychological assessment.

Contextual factors play a very large role in determining the final scores obtained on psychological tests, so contextual factors must therefore be considered 🡪 contribute to method variance. However, trying to document the validity of individualised, contextually included conclusions is very complex.

The validity of psychological tests is comparable to the validity of medical tests.

Distinct assessment methods provide unique sources of data 🡪 sole reliance on a clinical interview often leads to an incomplete understanding of patients.

It is argued that optimal knowledge in clinical practice/research is obtained from the sophisticated integration of information derived from a multimethod assessment battery.

Clinical diagnostics is based on 3 elements:

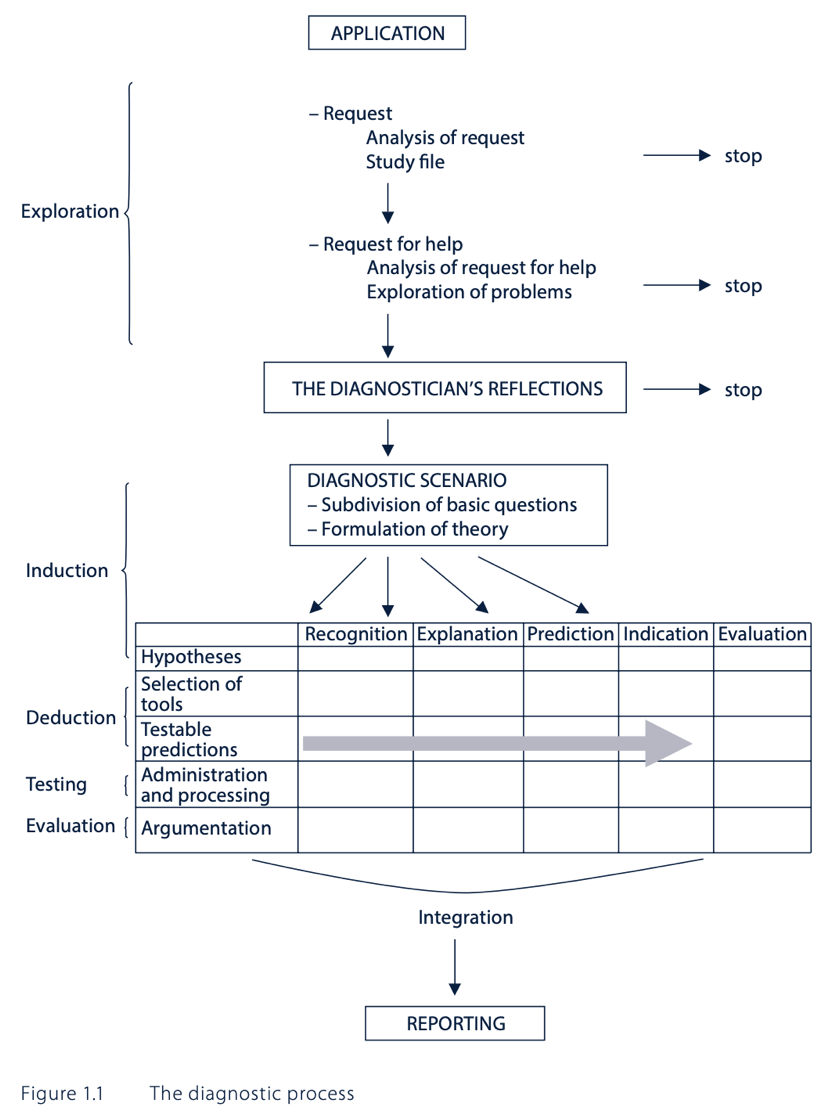

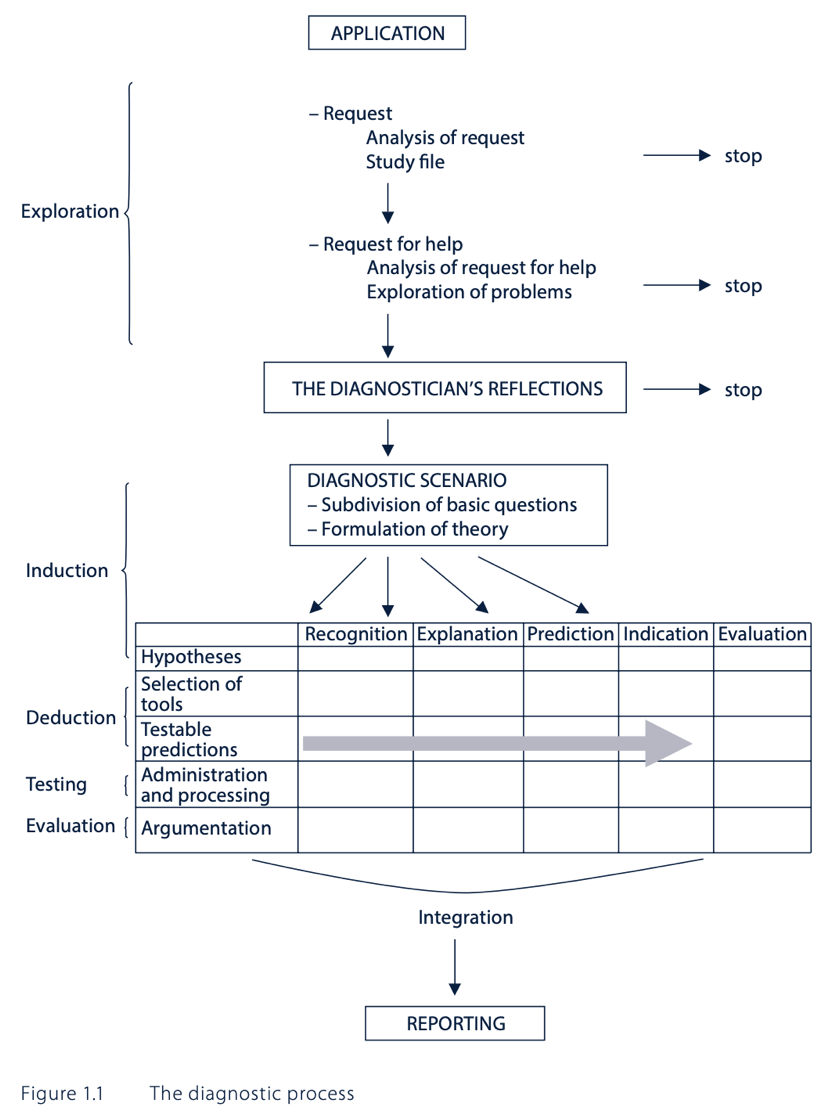

Testing a diagnostic theory requires 5 diagnostic measures:

formulated hypotheses

order to give a clear indication as to when the hypotheses should be accepted

or rejected

the hypotheses have either been accepted or rejected

This results in the diagnostic conclusion.

5 basic questions in clinical psychodiagnostics – classification of requests:

The quantity and type of basic questions to be addressed depends on the questions that were discussed during the application phase. Most requests contain 3 basic questions: recognition, explanation, and indication. In practice, all the basic questions chosen are often examined simultaneously.

Recognition:

Explanation:

Prediction:

Indication:

Evaluation:

Diagnostic cycle = a model for answering questions in a scientifically justified manner:

The diagnostic cycle is a basic diagram for scientific research, not for psychodiagnostic practice.

The diagnostic process:

Critical comments on DTCs:

BDI-II:

Sensitivity = the number of individuals we can correctly diagnose with depression 🡪 from the 100 people receiving a diagnosis, 86 would be diagnosed with depression correctly 🡪 the other 14 individuals are false negatives.

Specificity = the number of individuals we can correctly diagnose as healthy 🡪 from the 100 people receiving a diagnosis, 78 would be diagnosed healthy correctly 🡪 the other 22 individuals are false positives.

The Youden criterion (= sensitivity + specificity) is not always correct 🡪 it may give counterintuitive results in some circumstances.

Based on BDI-II scores alone:

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory is the same as the Self Confidence Test. Narcissists could underreport on psychological tests as they want to do good and won’t show they are suffering from a disease.

Kohut’s self-psychology approach offers the deficit model of narcissism, which asserts that pathological narcissism originates in childhood because of the failure of parents to empathise with their child.

Kernberg’s object relations approach emphasises aggression and conflict in the psychological development of narcissism, focusing on the patient’s aggression towards and envy of others 🡪 conflict model.

Social critical theory (Wolfe) 🡪 narcissism was a result of the collective ego’s defensive response to industrialisation and the changing economic and social structure of society.

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), DSM-V criteria:

or ideal love

DSM-IV mainly focused on the disorder’s grandiose features and did not adequately capture the underlying vulnerability that is evident in many narcissistic individuals.

At least 2 subtypes or phenotypic presentations of pathological narcissism can be differentiated:

defensive and anxious about an underlying sense of shame and inadequacy 🡪 thin-skinned

The former defending the latter: grandiosity conceals underlying vulnerabilities

Both individuals with grandiose and those with vulnerable narcissism share a preoccupation with satisfying their own needs at the expense of the consideration of others.

Pathological narcissism is defined by a fragility in self-regulation, self-esteem, and sense of agency, accompanied by self-protective reactivity and emotional dysregulation.

Grandiose and self-serving behaviours may be understood as enhancing an underlying depleted sense of self and are part of a self-regulatory spectrum of narcissistic personality functioning.

Psychodynamic approaches:

Cognitive-behavioural approaches:

Treatment challenges:

specialness and/or may accentuate feelings of low self-worth, shame and

humiliation.

pharmacological interventions.

The mainstay of treatment for NPD is psychological therapy.

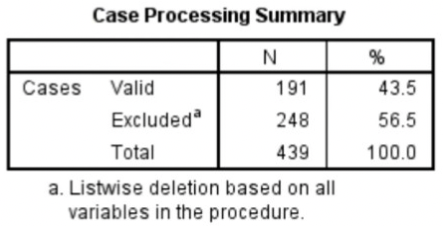

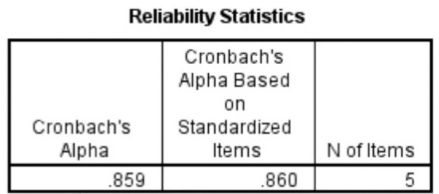

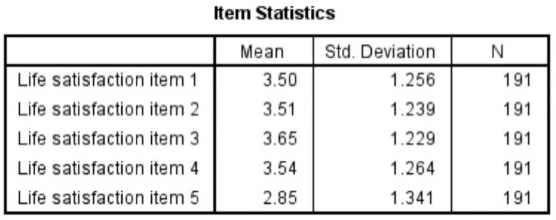

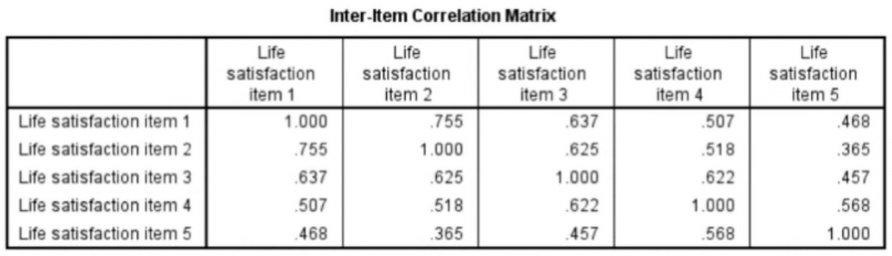

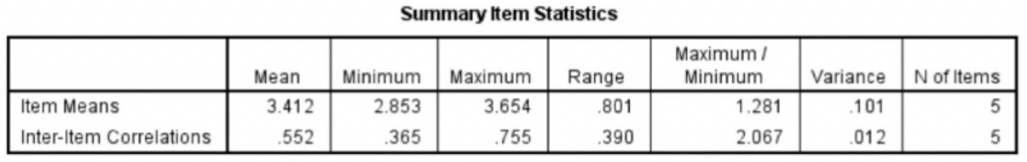

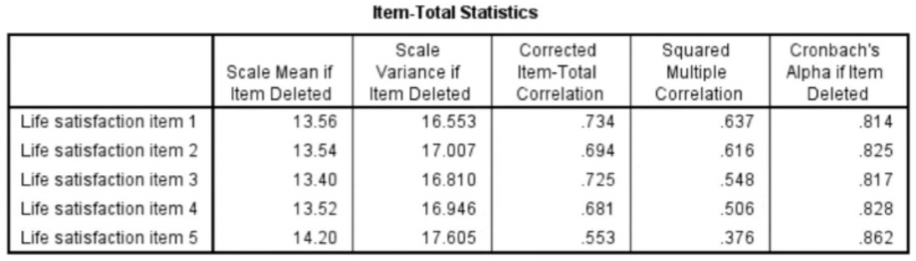

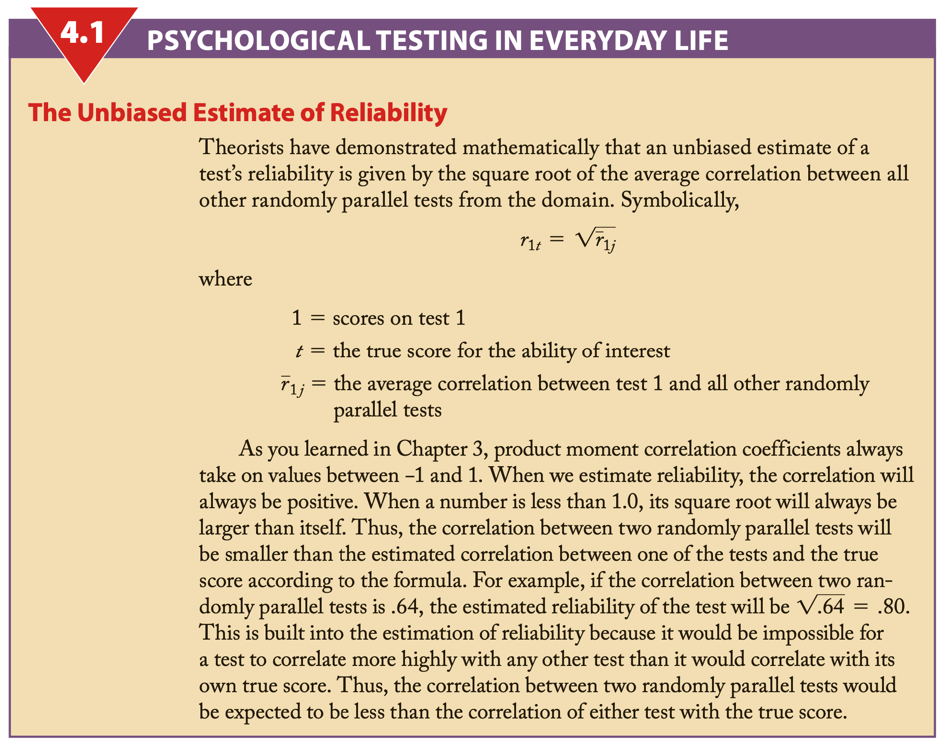

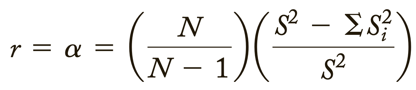

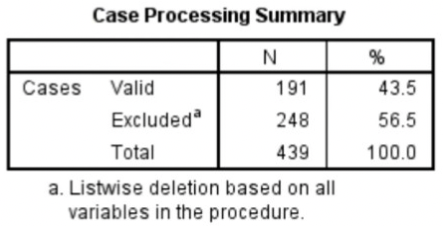

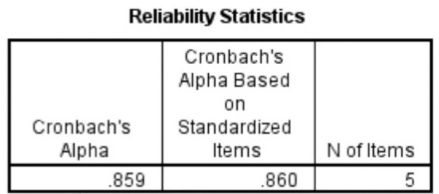

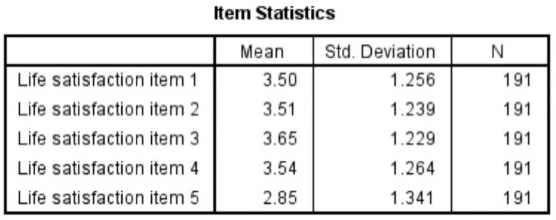

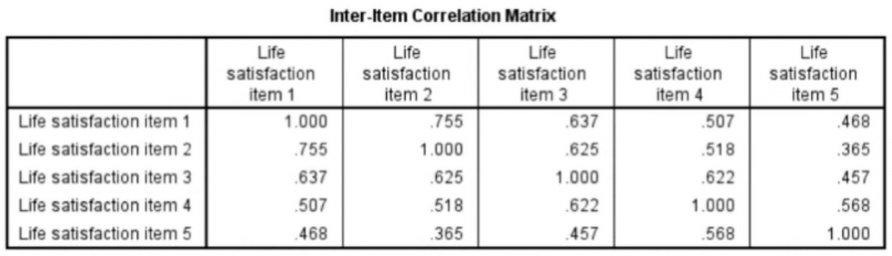

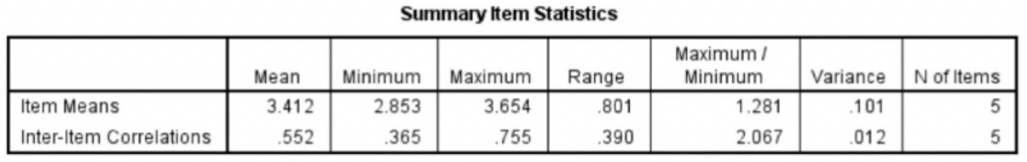

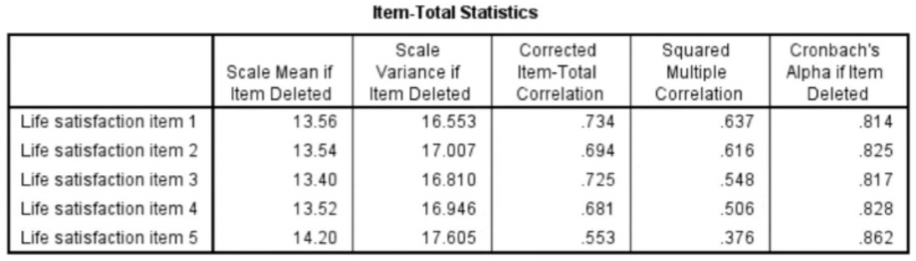

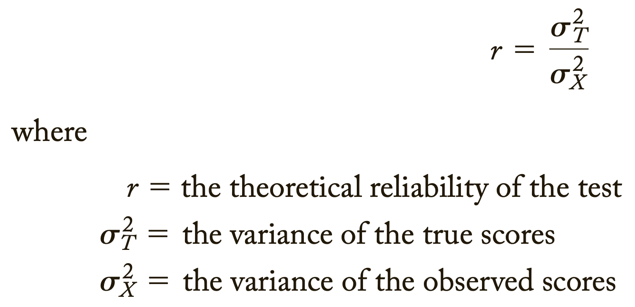

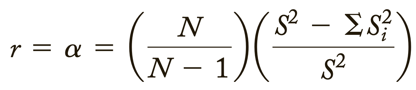

Cronbach’s Alpha = a psychometric statistic

Before Cronbach’s Alpha:

Cronbach’s Alpha is much more general than these two 🡪 it represents the average of all possible split-halves. In addition, it can be used for both dichotomous and continuously scored data/variables.

Coefficient Alpha = Cronbach' Alpha

What is it?:

Cronbach’s Alpha is a coefficient, and it can range from 0.00 to 1.00.

Internal consistency reliability is relevant to composite scores = the sum (or average) of 2 or more scores.

Cronbach’s Alpha measures internal consistency between items on a scale.

The steps needed to generate the relevant output in SPSS:

Interpreting Cronbach’s Alpha output from SPSS:

High Cronbach’s Alpha: suggests that a questionnaire might contain unnecessary duplication of content.

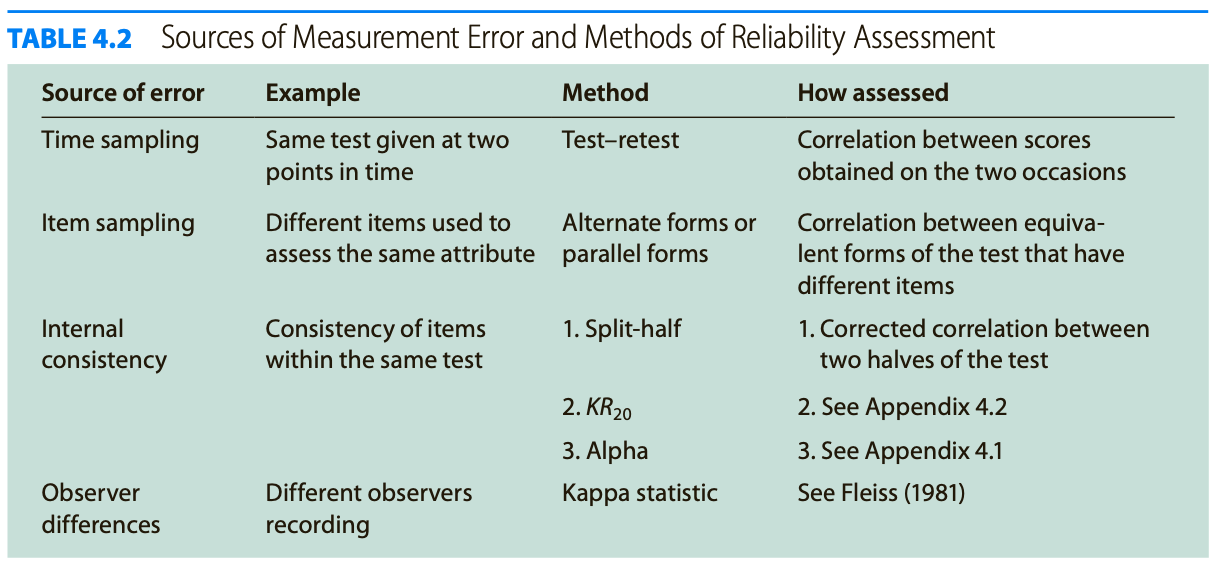

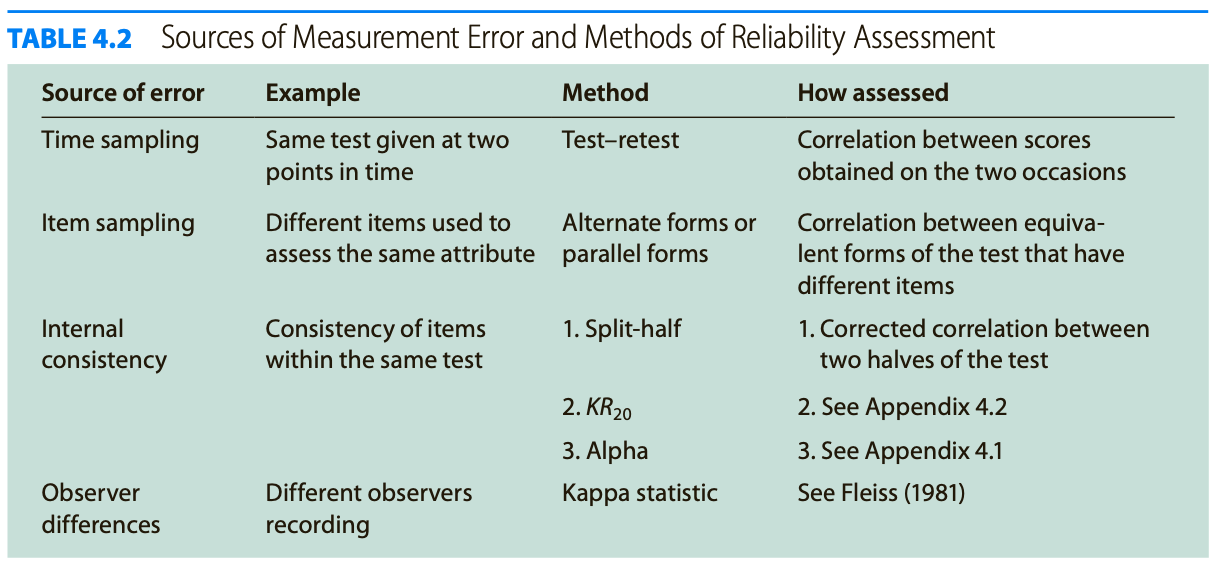

Reliability = how consistently a method measures something.

There are 4 main types of reliability 🡪 each can be estimated by comparing different sets of results produced by the same method.

Test-retest reliability:

Interrater reliability/interobserver reliability:

Parallel forms reliability:

Internal consistency:

Which type of reliability applies to my research?:

Summary types of reliability:

Test-retest reliability The same test over time Measuring a property that you expect to stay the same over time | You devise a questionnaire to measure the IQ of a group of participants (a property that is unlikely to change significantly over time). You administer the test 2 months apart to the same group of people, but the results are significantly different, so the test-retest reliability of the IQ questionnaire is low. |

|---|---|

Interrater reliability/interobserver reliability The same test conducted by different people Multiple researchers making observations or ratings about the same topic | A team of researchers observe the progress of wound healing in patients. To record the stages of healing, rating scales are used, with a set of criteria to assess various aspects of wounds. The results of different researchers assessing the same set of patients are compared, and there is a strong correlation between all sets of results, so the test has high interrater reliability. |

Parallel forms reliability Different versions of a test which are designed to be equivalent Using 2 different tests to measure the same thing | A set of questions is formulated to measure financial risk aversion in a group of respondents. The questions are randomly divided into 2 sets, and the respondents are randomly divided into 2 groups. Both groups take both tests: group A takes test A first, and group B takes test B first. The results of the 2 tests are compared, and the results are almost identical, indicating high parallel forms reliability. |

Internal consistency The individual items of a test Using a multi-item test where all the items are intended to measure the same variable | A group of respondents are presented with a set of statements designed to measure optimistic and pessimistic mindsets. They must rate their agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 to 5. If the test is internally consistent, an optimistic respondent should generally give high ratings to optimism indicators and low ratings to pessimism indicators. The correlation is calculated between all the responses to the “optimistic” statements, but the correlation is very weak. This suggests that the test has low internal consistency. |

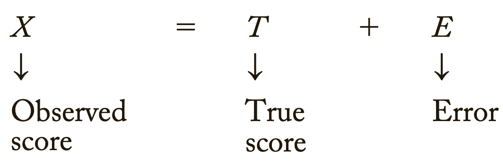

Errors of measurement = discrepancies between true ability and measurement of ability

Tests that are relatively free of measurement error: reliable

Tests that have “too much” measurement error: unreliable

Classical test score theory = assumes that each person has a true score that would be obtained if there were no errors in measurement.

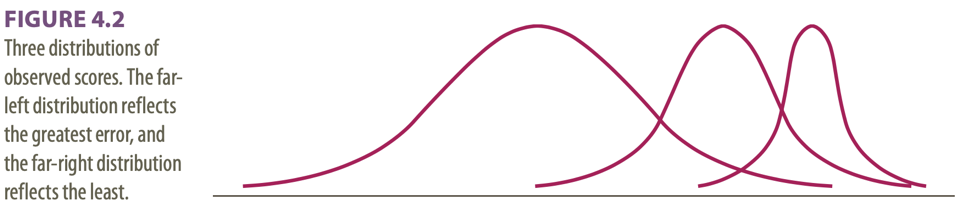

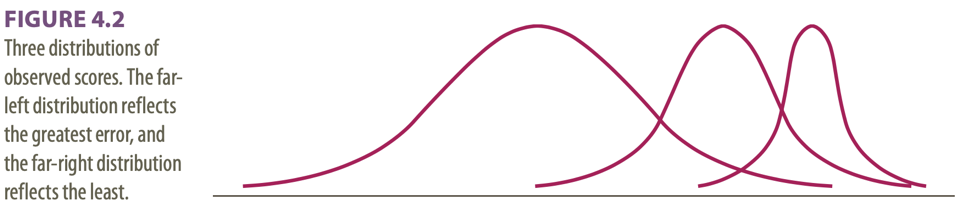

3 different distributions shown:

Dispersions around the true score: tell us how much error there is in the measure

Classical test theory assumes that the true score for an individual will not change with repeated applications of the same test 🡪 because of random error, repeated applications of the same test can produce different scores 🡪 random error is responsible for the distribution of scores.

The standard deviation of the distribution of errors for each person tells us about the magnitude of measurement error.

Domain sampling model = considers the problems created by using a limited number of items to represent a larger and more complicated construct 🡪 another central concept in classical test theory.

As the sample gets larger, it represents the domain more and more accurately 🡪 the greater the number of items 🡪 the higher the reliability

Because of sampling error, different random samples of items might give different estimates of the true score: true scores are not available so need to be estimated.

Turning away from classical test theory because it requires that the same test items be administered to each person 🡪 low reliability when few items.

Item response theory (IRT) = the computer is used to focus on the range of item difficulty that helps assess an individual’s ability level.

Difficulties of IRT: requires a bank of items that have been systematically evaluated for level of difficulty 🡪 complex computer software is required and much effort in test development.

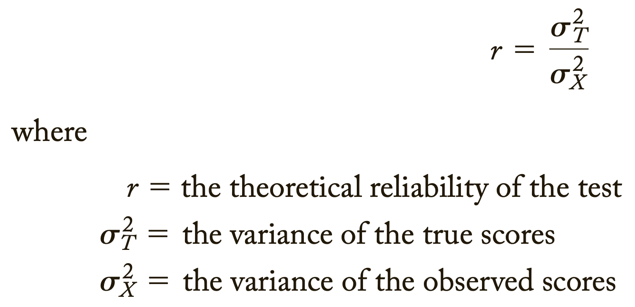

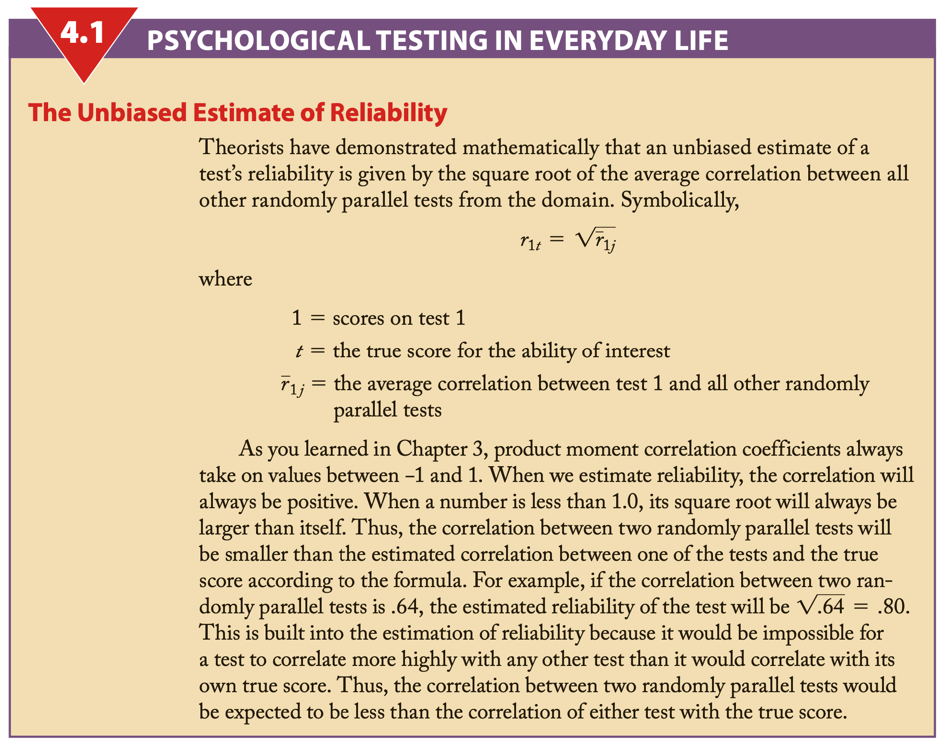

Reliability coefficient = the ratio of the variance of the true scores on a test to the variance of the observed scores.

σ2 = describes theoretical values in a population

S2 = values obtained from a sample

If r = .40: 40% of the variation or difference among the people will be explained by real differences among people, and 60% must be ascribed to random or chance factors.

An observed score may differ from a true score for many reasons.

Test reliability is usually estimated in 1 of 3 ways:

Test-retest method:

Parallel forms:

Internal consistency:

Factor analysis = popular method for dealing with the situation in which a test apparently measures several different characteristics.

Difference score = created by subtracting one test from another

Psychologists with behavioural orientations usually prefer not to use psychological tests 🡪 direct observation of behaviour.

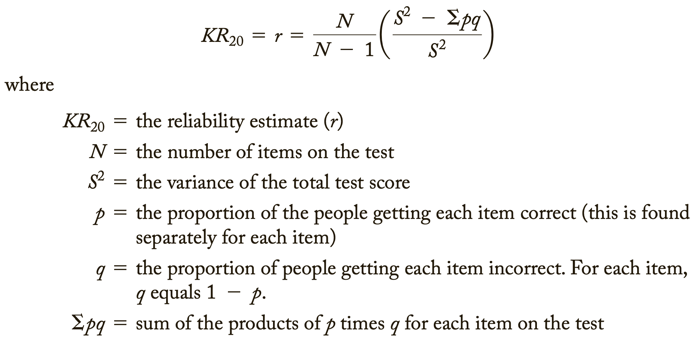

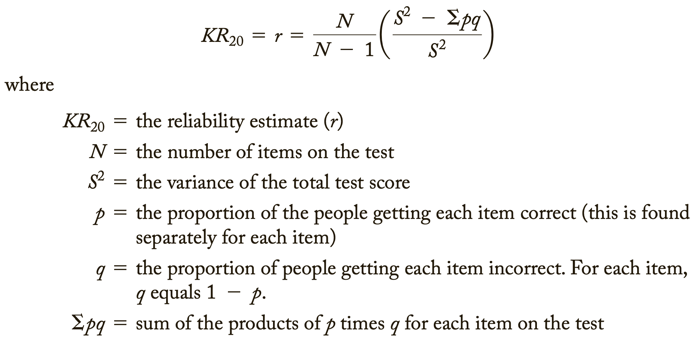

2 of 3 ways of measuring this type of reliability:

Standard reliability of a test depends on the situation in which the test will be used:

When a test has an unacceptable low reliability 2 approaches are:

2 approaches to ensure that items measure the same thing:

Low reliability 🡪 findings/correlation not significant 🡪 potential correlations are attenuated, or diminished, by measurement error 🡪 obtained information has no value

Adding more questions to heighten the reliability can be dangerous: it can impact the validity and it takes more time to take the test.

Too high reliability 🡪 remove redundant items/items that do not add anything 🡪 we want some error

Great instruction goes together with a high reliability.

For research rules are less strict than for individual assessment.

The Dutch Committee on Testing (COTAN) of the Dutch Psychological Association (NIP) publishes a book containing ratings of the quality of psychological tests.

The COTAN adopts the information approach, which entails the policy of improving test use and test quality by informing test constructors, test users, and test publishers about the availability, the content, and the quality of tests.

2 key instruments used are:

The 7 criteria of the Dutch Rating System for Test Quality:

Quality of Dutch tests:

Overall picture is positive showing that the quality of the test repertory is gradually improving.

Standards for educational and psychological testing; 3 sections:

Validity = does the test measure what it is supposed to measure?

Validity is the evidence for inferences made about a test score.

3 types of evidence:

Every time we claim that a test score means something different from before, we need a new validity study 🡪 ongoing process.

Subtypes of validity:

Examples of the subtypes of validity:

Face validity Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims? | You create a survey to measure the regularity of people’s dietary habits. You review the survey items, which ask questions about every meal of the day and snacks eaten in between for every day of the week. On its surface, the survey seems like a good representation of what you want to test, so you consider it to have high face validity. |

|---|---|

Content validity Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure? | A mathematics teacher develops an end-of-semester algebra test for her class. The test should cover every form of algebra that was taught in the class. If some types of algebra are left out, then the results may not be an accurate indication of student’s understanding of the subject. Similarly, if she includes questions that are not related to algebra, the results are no longer a valid measure of algebra knowledge. |

Criterion validity Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome that they are designed to measure? | A university professor creates a new test to measure applicants’ English writing ability. To assess how well the test really does measure students’ writing ability, she finds an existing test that is considered a valid measurement of English writing ability and compares the results when the same group of students take both tests. If the outcomes are very similar, the new test has high criterion validity. |

Construct validity Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure? | There is no objective, observable entity called “depression” that we can measure directly. But based on existing psychological research and theory, we can measure depression based on a collection of symptoms and indicators, such as low self-confidence and low energy levels. |

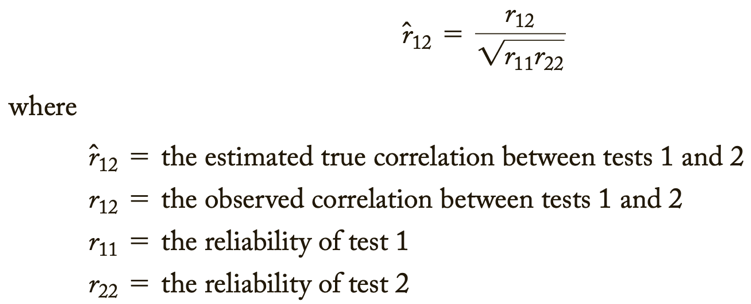

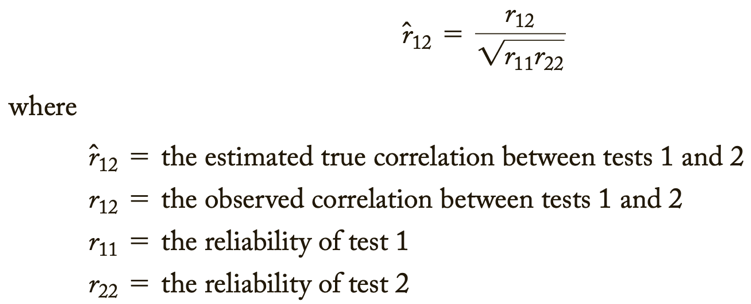

Validity coefficient = correlation that describes the relationship between a test and a criterion 🡪 tells the extent to which the test is valid for making statements about the criterion.

Because not all validity coefficients of .40 have the same meaning, you should watch for several things in evaluating such information 🡪 evaluating validity coefficients:

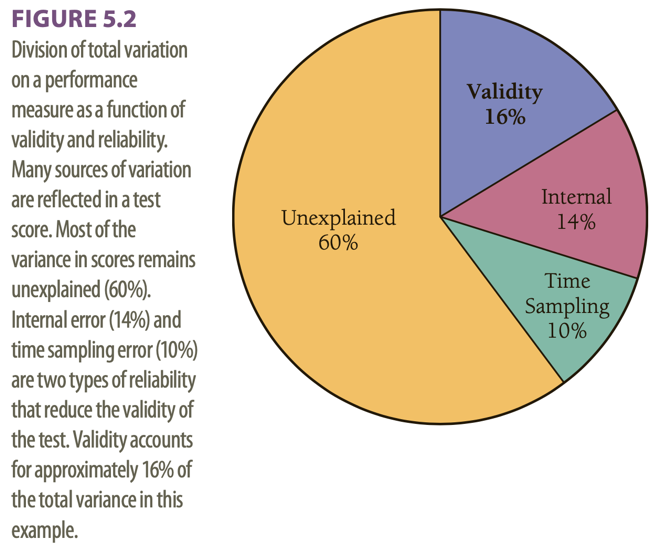

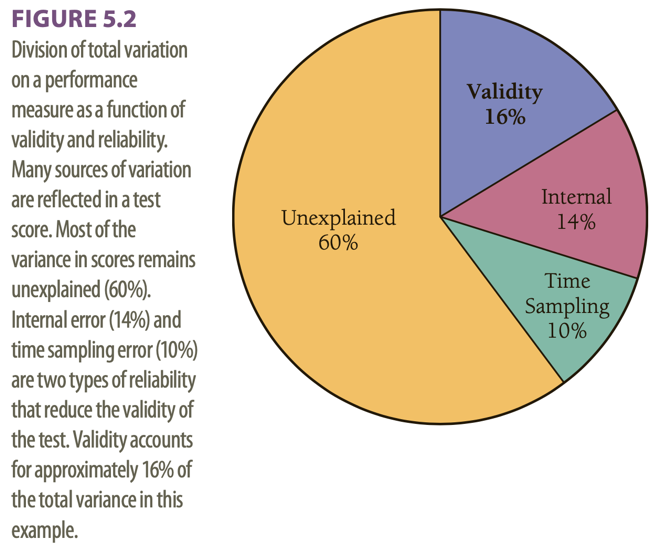

Relationship between reliability and validity:

The total variation of a test score into different parts:

This example has a validity coefficient of .40.

Assessment of personality relies heavily on self-report measures.

Can people be trusted in what they say about themselves? 🡪 it is preferable to maximize the validity by combining self-report approach with other methods, such as informant reports and observational measures.

Hofstee’s definition of personality: in terms of intersubjective agreement.

Preconceptions: informant methods for personality assessment are time-consuming, expensive, ineffective, and vulnerable to faking or invalid responses.

Still, in daily clinical practice, systematically collecting information from others than the client is not common use. Clinicians generally use interview and observation techniques to determine personality and psychopathology.

Multiple informant information on client personality and psychopathology is not embraced by clinicians.

Level of self-other (dis)agreement:

Moderators of self-other agreement:

Self-assessment in clinical research has most validity.

Most reliable information yielded from assessment of others.

Other studies are based on the assumptions that each of the 2 sources of information yields unique information.

Aggregate ratings by multiple informants correlated higher with observed behaviour than did self-ratings, thus, yielding more accurate information.

Information from others added value when it came to predicting limitations and interpersonal problems, or depressive symptoms and personality characteristics.

We need to examine the content of disagreement.

Reasons for substantial disagreements between couples:

2 hypotheses:

Results:

2 conclusions:

Larger disagreement between self-evaluation and evaluation by someone else: can signal presence of personality pathology as well as a greater risk of dropout.

SCID-5-S: Het gestructureerd klinisch interview voor DSM-5 Syndroomstoornissen

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale

Task 4 – Andrew’s problems become clear

Caldwell: anecdotal interpretation, selectively relating his experiences, without scientific data 🡪 referring to clinical experience to validate his use of a test.

2 traditional reactions on this/him in clinical psychology:

2 extremes 🡪 most of the time it is a mix.

Both empiricists and romanticists base their judgments on a combination of scientific findings, informal observations, and clinical lore 🡪 empiricists place a greater emphasis on scientific findings.

Research supports the empiricist tradition 🡪 it can be surprisingly difficult to learn from informal observations, both because clinicians’ cognitive processes are fallible and because accurate feedback on the validity of judgements is frequently not available in clinical practice. Furthermore, when clinical lore is studied, it is often found to be invalid.

2 new approaches to evaluating the validity of descriptions of personality and psychopathology:

Cognitive heuristics and biases: used to describe how clinical psychologists and other people make judgements.

In conclusion: psychologists should reduce their reliance on informal observations and clinical validation when:

Anchoring = the tendency to fixate on specific features of a presentation too early in the diagnostic process, and to base the likelihood of a particular event on information available at the outset.

Anchoring is closely related to:

Diagnoses can be biased, e.g., by patient (race) and task (dynamic stimuli lacking predictability) characteristics.

Diagnostic anchor = diagnoses suggested in referral letters

In conclusion: referral diagnoses/anchors do seem to influence the correctness of the diagnoses of intermediate but not very experienced clinicians.

Intermediate/moderately experienced clinicians tend to process information distinctively differently 🡪 and perform differently.

Experience brings about a shift: from more deliberate, logical, step-by-step processing to more automatic, intuitive processing 🡪 increased experience = increased tendency to conclude in favour of first impressions.

The present study indicates that the quality of referral information is important, certainly for clinicians with a moderate amount of experience 🡪 when uncertain about the diagnosis it is best to omit a diagnosis instead of giving a wrong “anchor”

Diagnostic errors 🡪 diagnosis with x while disease y 🡪 death

Daniel Kahneman:

We fluidly switch back and forth between these.

Not 2 physically separate systems but represent a model that can help us better understand different ways the brain operates.

When making a diagnosis: system 1 automatically kicks in when we recognize a pattern in a clinical presentation. System 2 requires deliberate thinking 🡪 when not used 🡪 diagnostic errors.

System 1 thinking becomes more accurate as clinicians move through their careers (become more experienced) and it can recognize (more easily) atypical/variant presentations.

Types of cognitive mistakes that can lead to diagnostic errors:

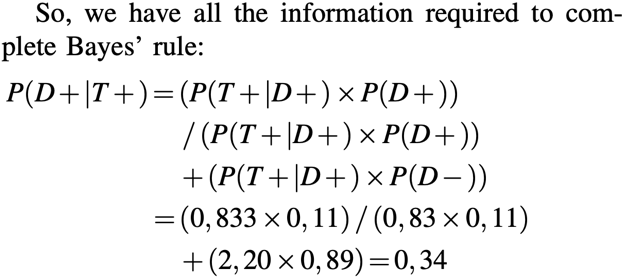

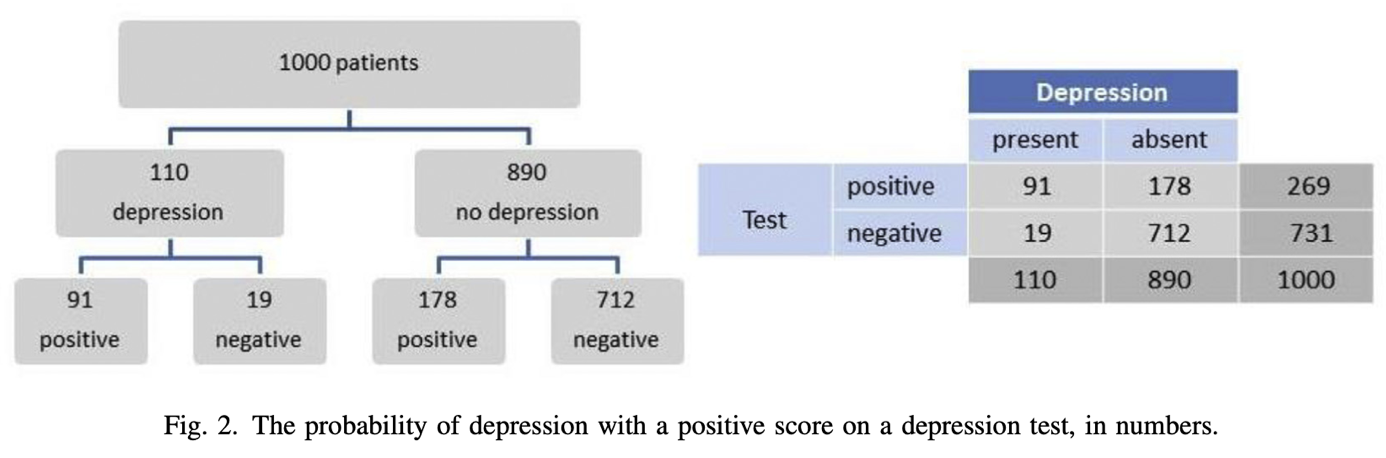

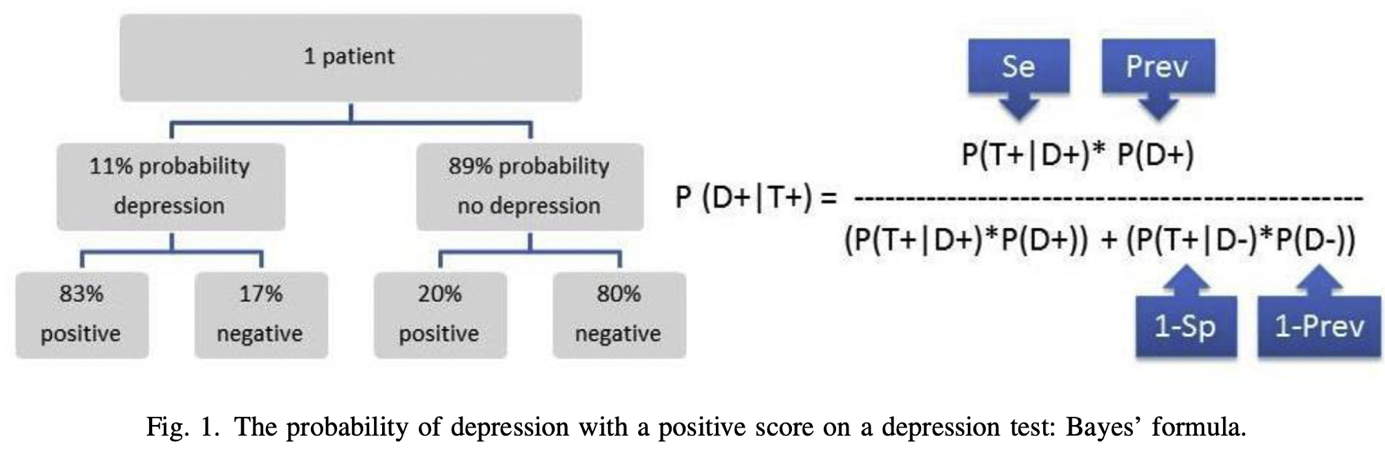

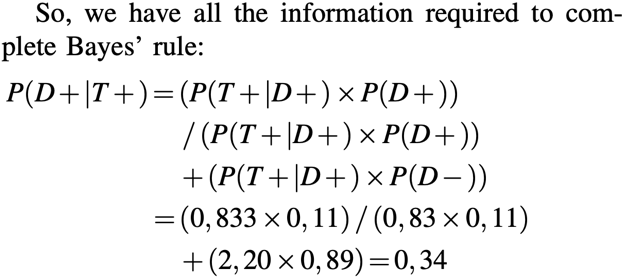

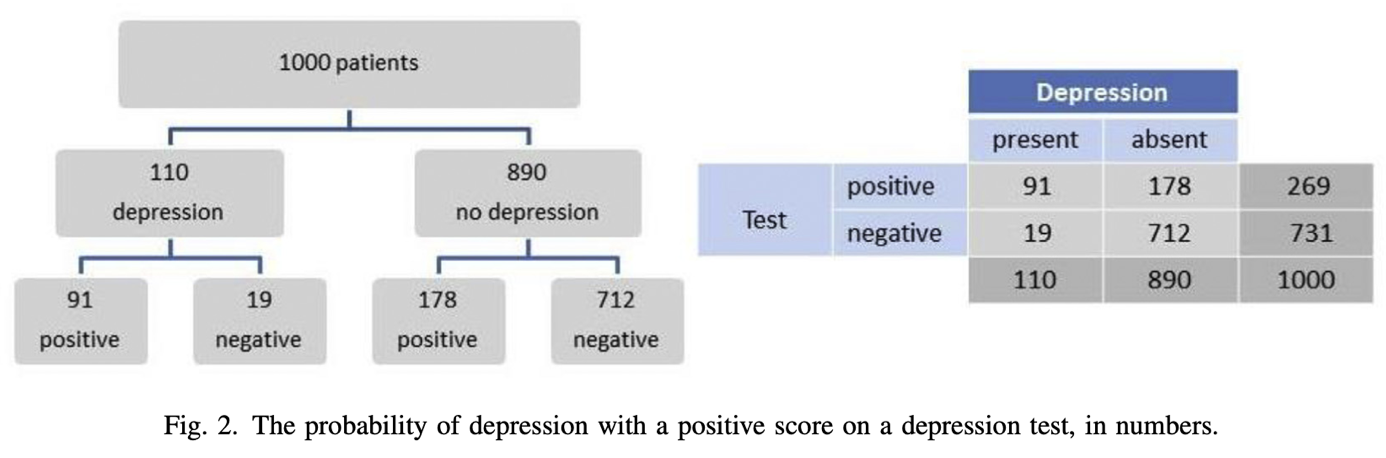

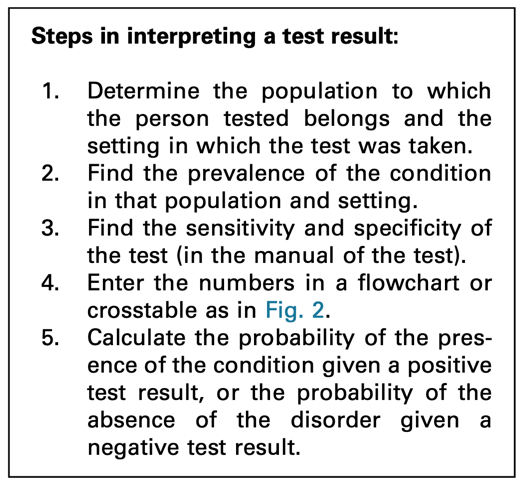

Bayes’ theorem/Bayes’ rule = a formula used to determine the conditional probability of events.

Bayes’ rule is designed to help calculate the posterior probability/post-test probability of an individual’s condition = the probability after the test has been taken and given the outcome of the test.

Based on 3 elements:

Sensitivity = number of individuals correctly diagnosed, the rest are false negatives

Specificity = number of individuals correctly seen as healthy, the rest are false positives

To use Bayes’ rule, it is essential to know: the prevalence of the condition in the population of which the individual is a member 🡪 leads to incorrect conclusions when skipped.

If in a given population a condition is rare (= low prevalence), the probability that the individual has the condition can never be high, even though it is higher with a positive test result than before the test outcome was known.

Different population 🡪 different prevalence of the condition 🡪 same test result leads to a different probability of the same condition

Not following Bayes’ rule properly 🡪 overdiagnosis 🡪 overtreatment

Prev = prevalence/base rate/pre-test probability in the GP’s population

P = probability/likelihood

| = under the condition that/given

D+ = having depression

T+ = positive test result

So, P(D+|T+) means: the probability (P) that the client has a depression (D+) given (|) a positive test result (T+) on a depression questionnaire 🡪 in this case the BDI.

Thus, P(D+|T+) for this client from this GP population is about one third (34%) 🡪 posterior probability/post-test probability

34% is a low probability 🡪 too low for treatment indication

This test (the BDI) cannot be used to establish the presence of depression 🡪 if a clinician is aware of Bayes’ rule, extra diagnostics are needed in addition to administering the BDI.

The calculation is also easy to do with absolute numbers 🡪 steps summarized below.

Positive score: 91/(91+178) = 0,34

Negative score: 712/(19+712). = 0,97 (probability of no depression with a negative score)

Clinicians often forget to include the pre-test probability in their interpretation. If they do look further than the test result, they tend to only consider the sensitivity of a test. Typically, a positive test score is interpreted as the presence of the condition.

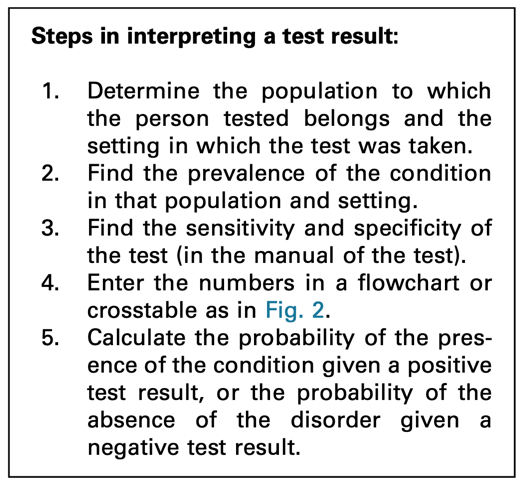

Clinicians that are aware of Bayes’ rule 🡪 when interpreting a test, they will take into consideration the setting in which the test was taken and the population to which the tested person belongs 🡪 they will establish the prevalence of the condition in that setting and population.

Sometimes general population, sometimes prevalence in clinicians’ practice or institute is more relevant.

It is recommended to use the information of your own institute or organization about prevalence of a certain disorder or disease.

Ignoring Bayes’ rule = overdiagnosis of conditions with a low pre-test probability (= not prevalent) 🡪 with low prevalence the “no disorder or disorder” group is very large, the post-test probability will remain low even with very high specificity, despite the large numbers of people who have a depression and who tested positive.

Making the error of omitting to take prevalence into account 🡪 major consequences for treatment policy 🡪 and thus for the course of a client’s symptoms.

You should not simply rely on the score of a test. Neither can we rely on the sensitivity and specificity only. Prevalence is also important.

Base rate problem:

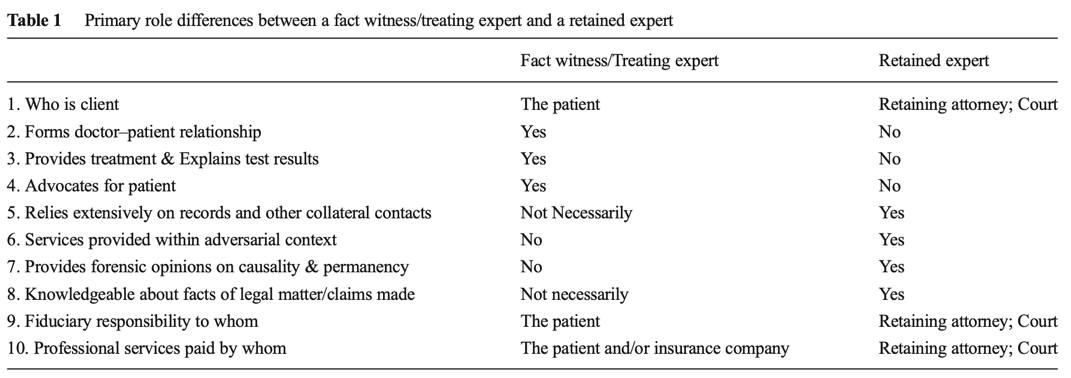

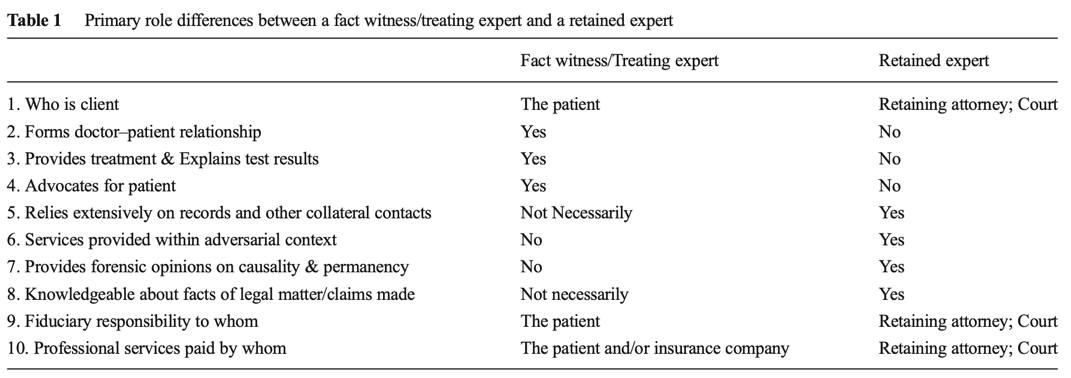

12 common biases in forensic neuropsychology 🡪 encountered in evaluation or provision of expert opinions and testimony.

Tackling point: do not take 2 roles at once.

Tackling point: be very careful with getting paid and make clear for what you are being paid.

Tackling point: be critical with forming a professional opinion about the case, do not just say something because you always handle defense cases.

Tackling point: make use of supporting data to form an opinion.

Tackling point: know the prevalence.

Tackling point: know when test scores are abnormal.

Tackling point: treat the diagnostic process with care and always have 2 hypotheses.

Tackling point: be alert for personal and political bias.

Tackling point: analyse interviews to see if there aren’t symptoms that are being missed just because someone is presenting in a certain way.

Tackling point: critically review diagnosis and if possible, conduct your own investigation.

Tackling point: use complete data from the past and after the accident to have a good overview if capabilities were really that impaired.

Tackling point: same as with confirmation bias; make use of the concurrent hypothesis.

Bias will always exist, no matter what. Bias is also unaffected by years of experience in practice.

The diagnosis of mental disorders has 4 major goals:

Giving an accurate diagnosis is important for the correct identification of the problems and the best choice of intervention.

Essential problem in assessment and clinical diagnosis: the neglect of the role of cultural differences on psychopathology.

One way to conceptualize this problem is to use the ethnic validity model in psychotherapy 🡪 the recognition, acceptance, and respect for the presence of communalities and differences in psychosocial development and experiences among people with different ethnic or cultural heritages.

Useful to broaden this to cultural validity = the effectiveness of a measure or the accuracy of a clinical diagnosis to address the existence and importance of essential cultural factors, e.g., values, beliefs, communication patterns.

Problems because of the lack of cultural validity in clinical diagnosis:

Universalist perspective = assumes that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or culture develop along uniform psychological dimensions.

Threats to cultural validity are due to a failure to recognize or a tendency to minimize cultural factors in clinical assessment and diagnosis.

Sources of threats to cultural validity:

In conclusion, cultural factors are important to clinical diagnosis and assessment of psychopathology.

Recommendations to reduce sources of threats to cultural validity:

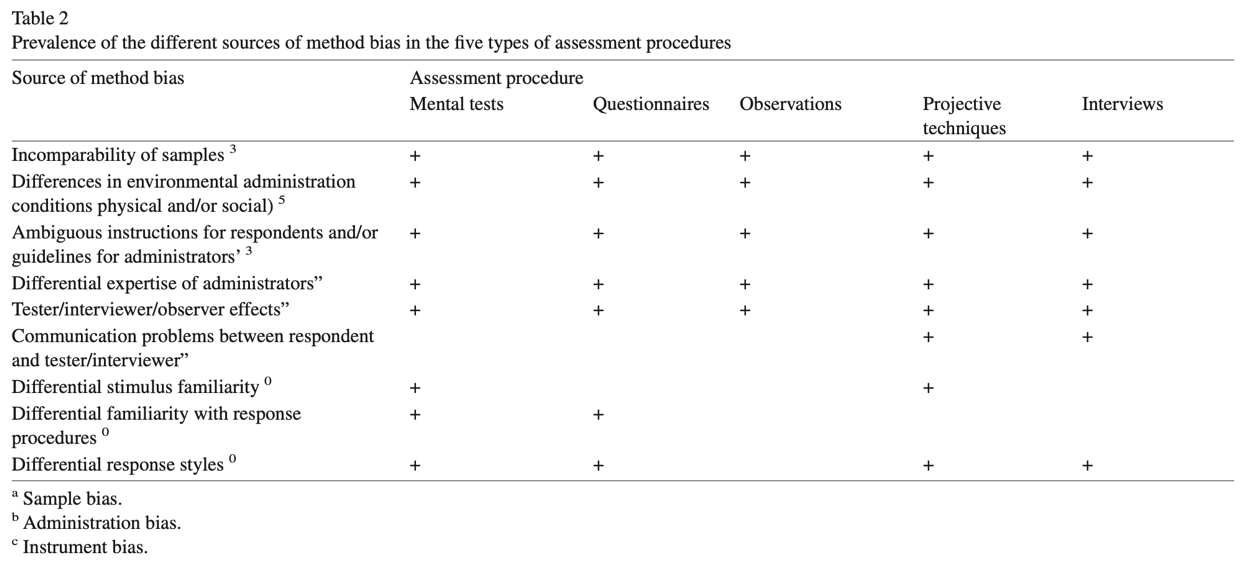

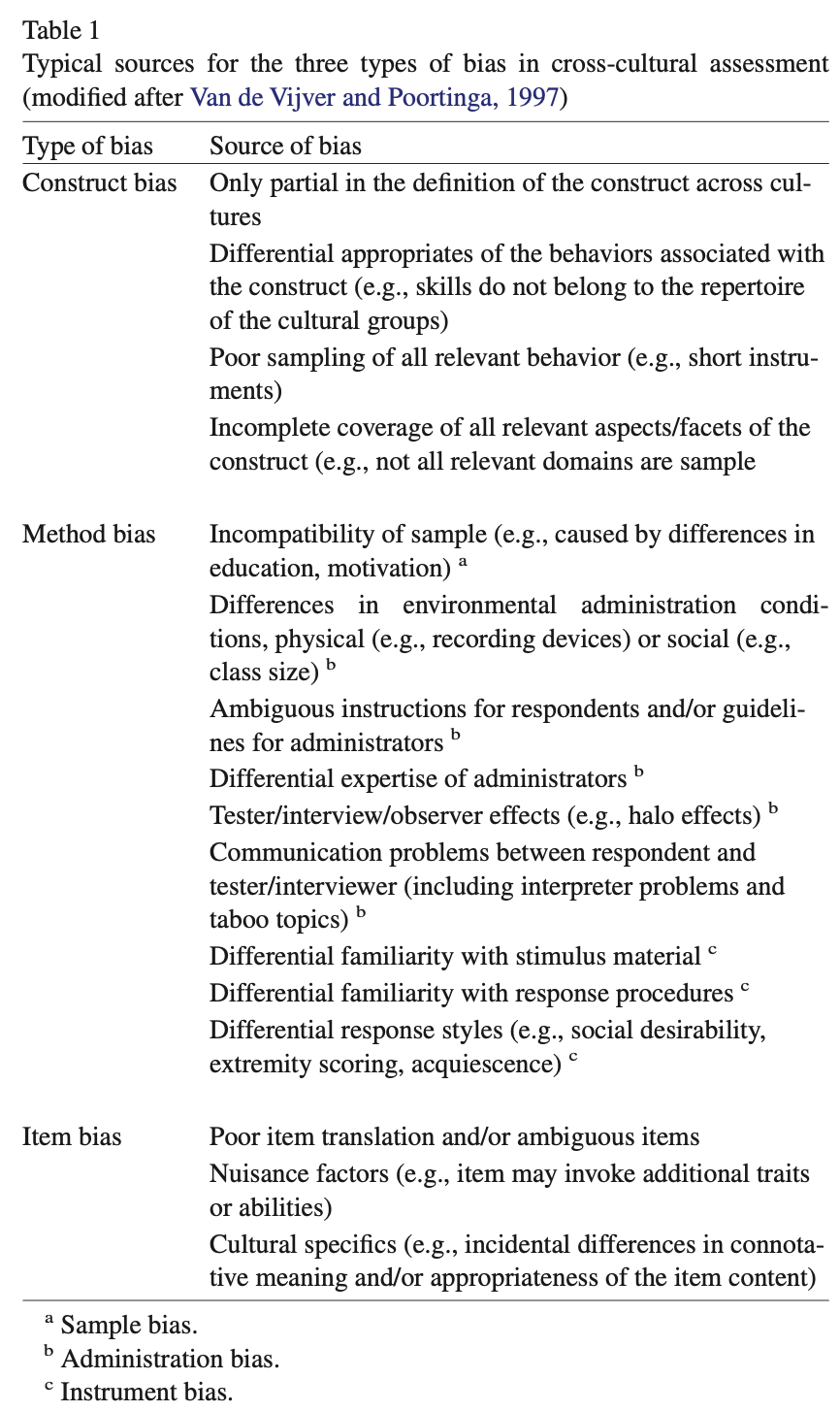

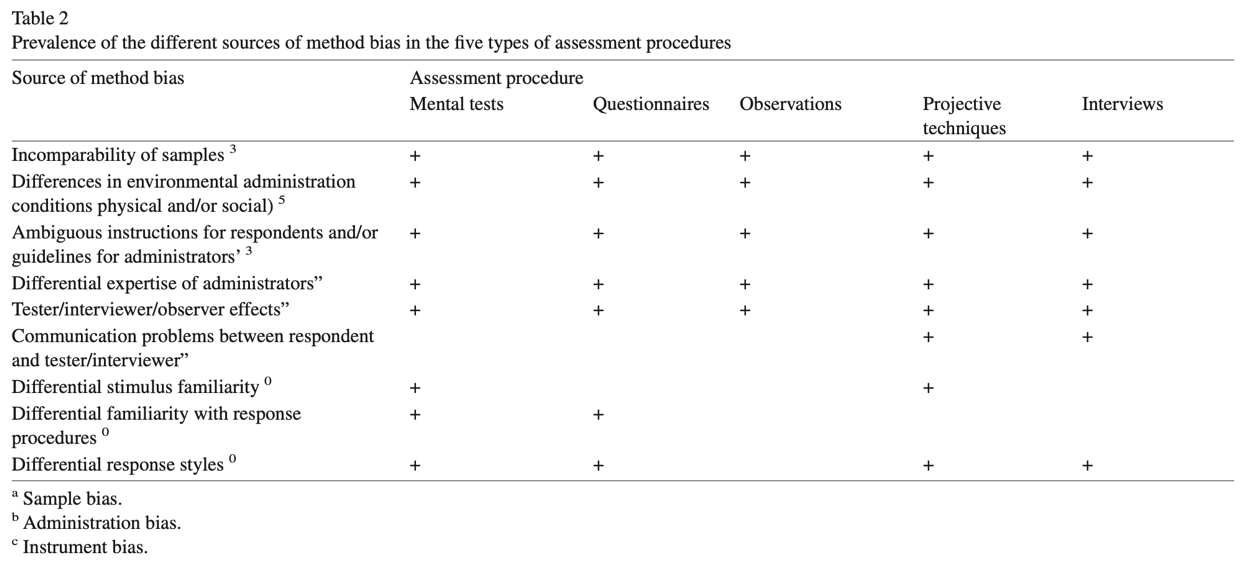

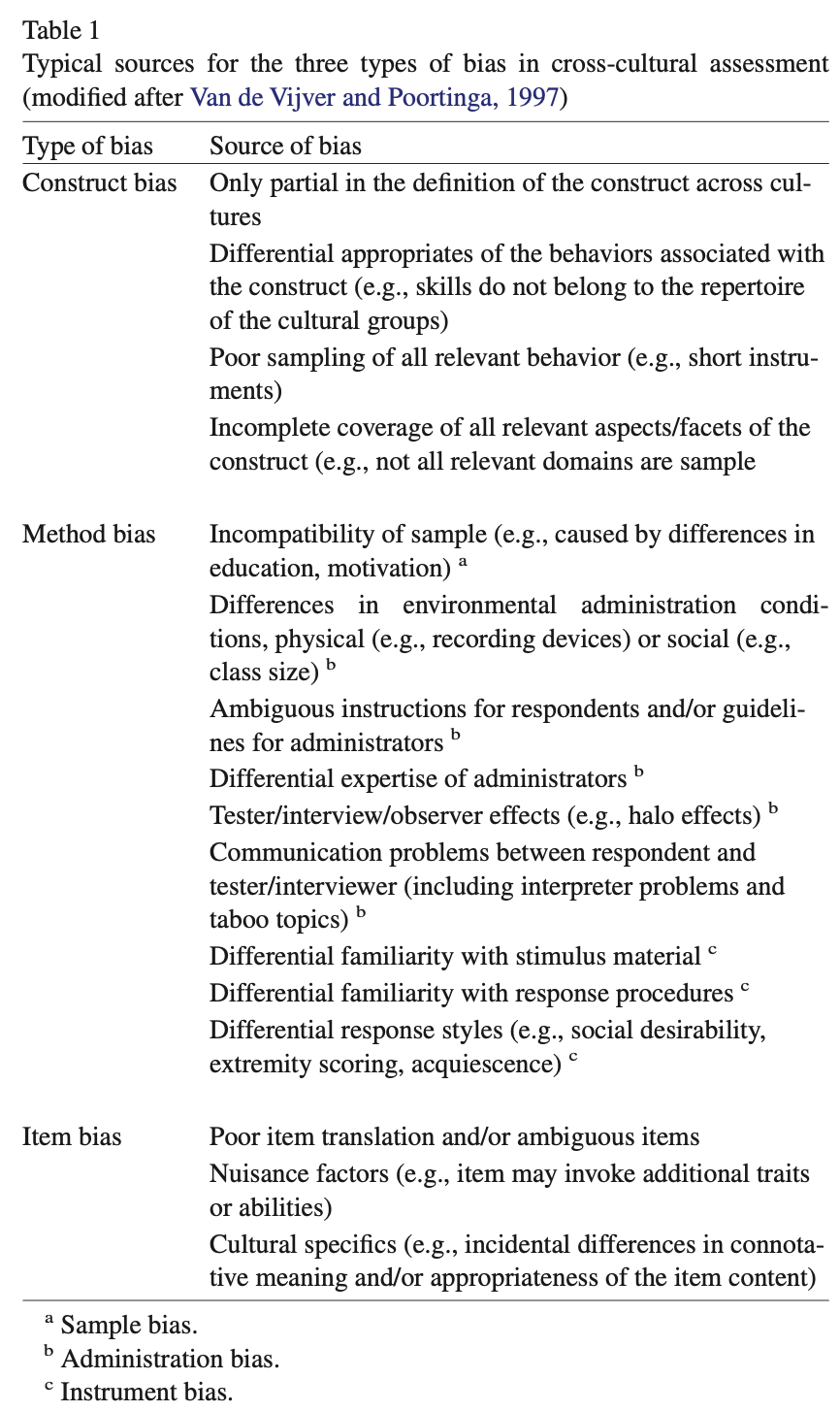

Bias = nuisance factors in cross-cultural score comparisons

Equivalence = more associated with measurement level issues in cross-cultural score comparisons

Thus, both are associated with different aspects of cross-cultural score comparisons of an instrument 🡪 they do not refer to intrinsic properties of an instrument.

Bias occurs if score differences on the indicators of a particular construct do not correspond to differences in the underlying trait or ability 🡪 e.g., percentage of students knowing that Warsaw is Poland’s capital – geography knowledge.

Inferences based on biased scores are invalid and often do not generalize to other instruments measuring the same underlying trait or ability.

Statements about bias always refer to applications of an instrument in a particular cross-cultural comparison 🡪 an instrument that reveals bias in a comparison of German and Japanese individuals may not show bias in a comparison of German and Danish subjects.

3 types of bias:

The likelihood of a certain type of bias will depend on:

Equivalence = measurement level at which scores can be compared across cultures.

Equivalence of measures (or lack of bias) is a prerequisite for valid comparisons across cultural populations 🡪 can be defined as the opposite of bias.

Hierarchically linked types of equivalence (from small to high):

Bias tends to challenge and can lower the level of equivalence:

An appropriate translation requires: a balanced treatment of psychological, linguistic, and cultural considerations 🡪 translation of psychological instruments involves more than rewriting the text in another language.

2 common procedures to develop a translation:

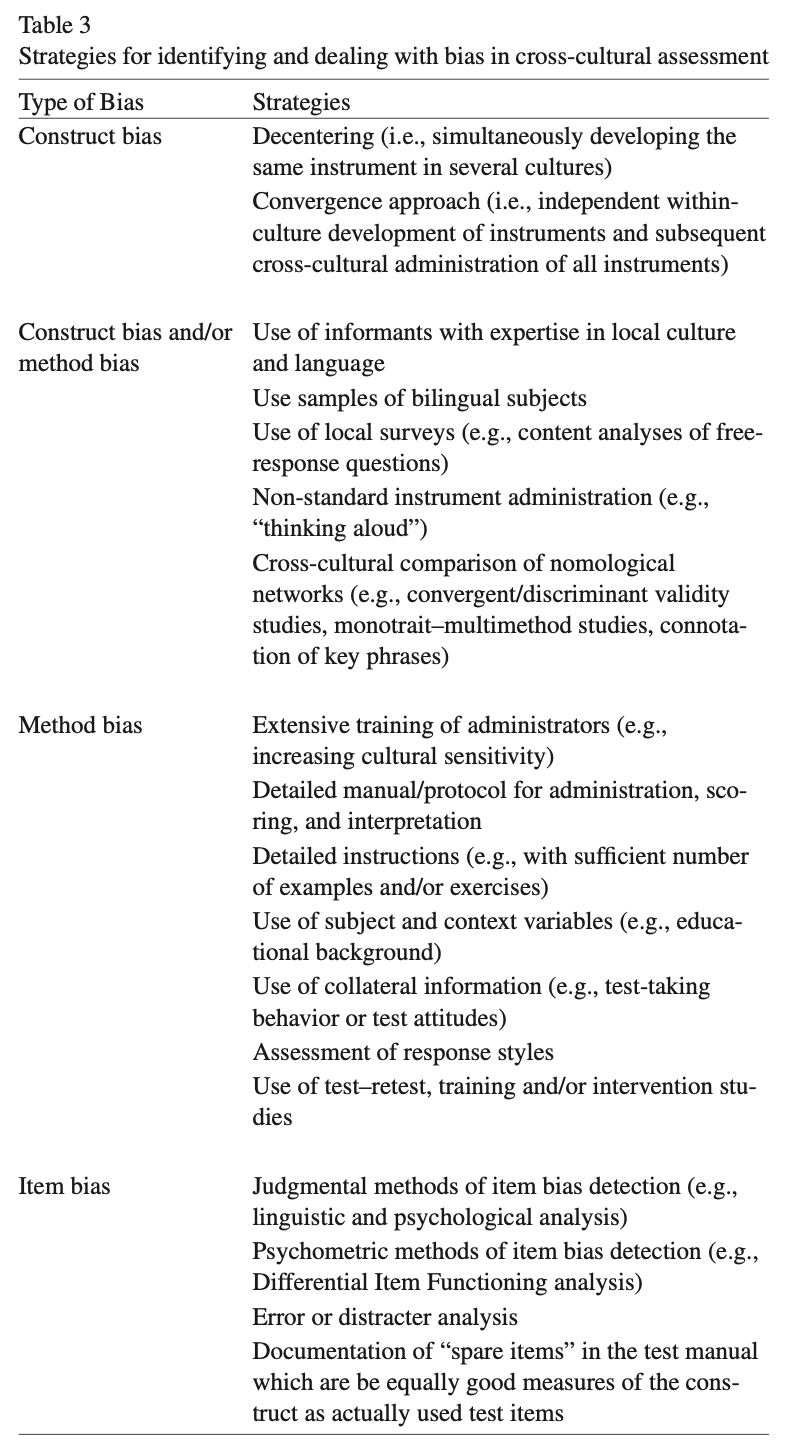

Remedies: most strategies implicitly assume that bias is a nuisance factor that should be avoided 🡪 there are techniques that enable the reduction and/or elimination of bias.

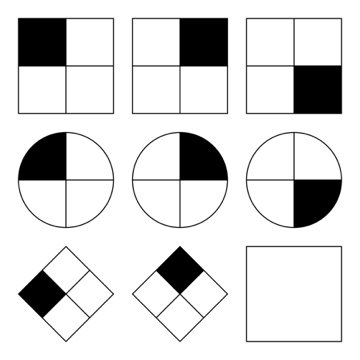

The most salient techniques for addressing each bias:

Construct bias:

Construct and/or method bias:

Method bias:

Item bias:

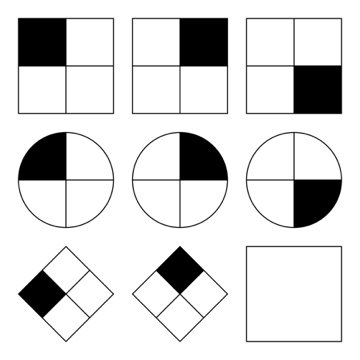

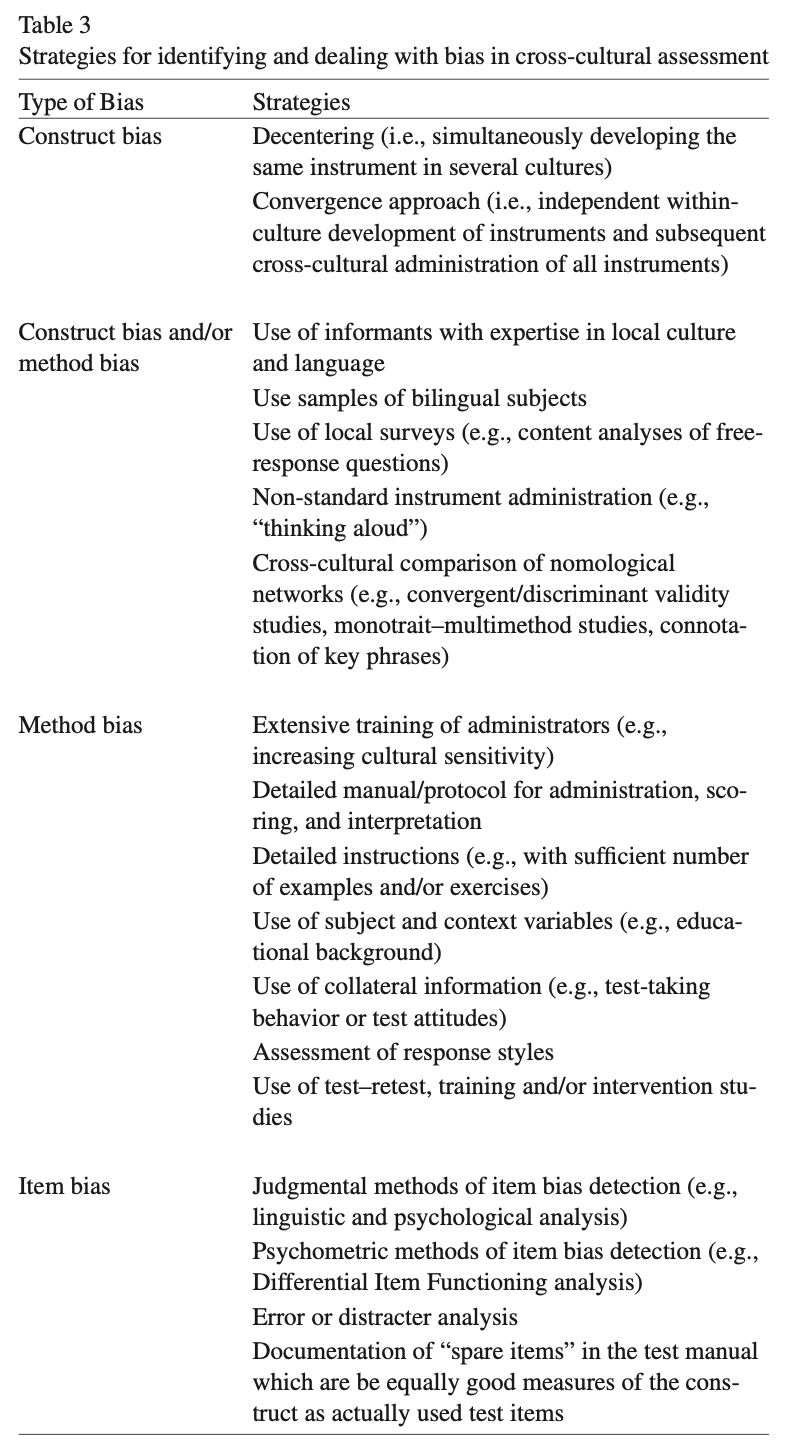

Raven’s Progressive Matrices/Raven’s Matrices/RPM = a non-verbal test typically used to measure general human intelligence and abstract reasoning and is regarded as a non-verbal estimate of fluid intelligence = the ability to solve novel reasoning problems and is correlated with several important skills such as comprehension, problem solving, and learning.

All the questions on the Raven’s progressives consist of visual geometric design with a missing piece 🡪 the test taker is given 6 to 8 choices to pick from and fill in the missing piece.

An IQ test item in the style of a Raven’s Progressive Matrices test. Given 8 patterns, the subject must identify the missing 9th pattern.

Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary tests were originally developed for use in research into the genetic and environmental origins of cognitive ability.

The Matrices are available in 3 different forms for participants of different ability:

In addition, "parallel" forms of the standard and coloured progressive matrices were published 🡪 to address the problem of the Raven's Matrices being too well known in the general population.

A revised version of the RSPM – the Standard Progressive Matrices Plus 🡪 based on the "parallel" version but, although the test was the same length, it had more difficult items in order to restore the test's ability to differentiate among more able adolescents and young adults than the original RSPM had when it was first published.

The tests were initially developed for research purposes.

Because of their independence of language and reading and writing skills, and the simplicity of their use and interpretation, they quickly found widespread practical application.

Flynn-effect = intergenerational increase/gains in IQ-scores around the world.

Individuals with ASS score high on Raven’s tests.

Therapeutic assessment (TA):

The client has specific questions 🡪 therapist/assessor tries to answer these questions with test results 🡪 by planning a battery that is in line with the client’s questions.

3 factors that make the change:

Clients who never improved from other treatment(s) do improve from TA.

Power of TA: the basic human need to be seen and understood

A person develops through the process of TA a more coherent, accurate, compassionate, and useful story about themselves.

Therapeutic assessment (TA) = semi-structured approach to assessment that strives to maximize the likelihood of therapeutic change for the client 🡪 an evidence-based approach to positive personal change through psychological assessment.

Development of TA:

Evidence for TA:

Growing number of research 🡪 TA is an effective therapeutic intervention

Ingredients of TA that explain the powerful therapeutic effects:

Steps in the TA process by Finn (and Tonsager):

Traditionally: assessment has focused on gathering accurate data to use in clarifying diagnoses and developing treatment plans.

New approaches: also emphasize the therapeutic effect assessment can have on clients and important others in their lives.

Steps that are not conducted in the traditional psychological assessment: first step, fourth step, seventh step.

Therapeutic assessment (TA) = a collaborative semi-structured approach to individualized clinical (personality) assessment.

psychiatric populations

The therapist and assessor were/are not the same person 🡪 indicating that the techniques practiced by TA providers to foster a therapeutic alliance model transfer to subsequent providers and might aid in treatment readiness and success.

TA can be effective in reducing distress, increasing self-esteem, fostering the therapeutic alliance, and, to a lesser extent, improving indicators of treatment readiness.

On the other hand, symptomatic and functional improvement has yet to be definitively demonstrated with adults.

In children, emerging evidence suggests that TA was associated with symptomatic improvement, but these studies suffer from small samples and nonrandomized designs.

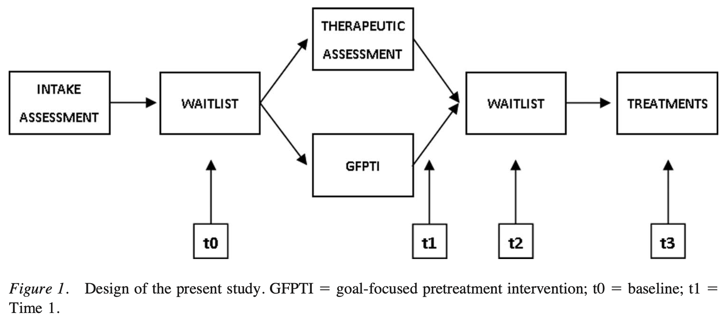

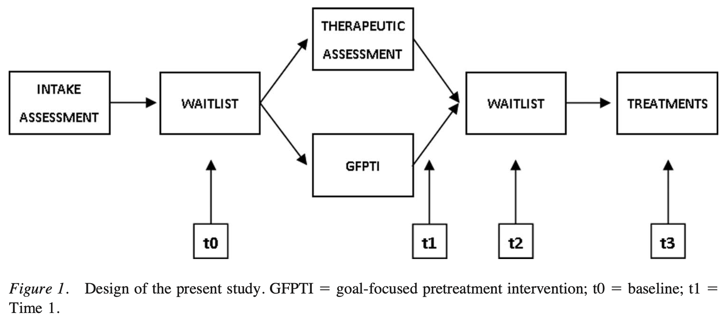

TA has not yet been empirically tested in patients formally diagnosed with personality disorders (PDs) 🡪 present study is a conduction of a pre-treatment RCT among patients with severe personality pathology awaiting an already assigned course of treatment.

2 conditions in the study:

Conclusions:

symptoms and demoralization improvements were observed.

Treatment utility is often defined as improving treatment outcome, typically in terms of short-term symptomatic improvement.

From the more inclusive view of treatment utility however, TA demonstrated stronger ability to prepare, motivate, and inspire the patient for the tasks of therapy, and to provide focus and goals for therapy.

The Netherlands Institute of Psychologists (NIP) is a national professional association promoting the interests of all psychologists. It has its own Code of Ethics = describes the ethical principles and rules that psychologists must observe in practicing their profession.

The objective of the NIP is to ensure psychologists work in accordance with high professional standards, and it guides and support psychologists’ decisions in difficult and challenging situations that they may face.

The Code of Ethics is based on 4 basic principles: responsibility, integrity, respect, and expertise. These basic principles have been elaborated into more specific guidelines.

Psychologists registered with NIP or members need to follow the principles/are obliged to.

It is a good tradition of the NIP to regularly examine the Code of Ethics 🡪 professional ethics are dynamic, so the information is updated regularly.

A Code of Ethics serves several purposes:

Basic principles:

The Dutch Association of Psychologists (NIP) has made a Code of Ethics for Psychologists and the new Guidelines for the Use of Tests 2017.

Psychodiagnostic instruments = instruments for determining someone’s characteristics with a view to making determinations about that person, in the context of advice to that person themselves, or to others about them, in the framework of treatment, development, placement, or selection.

2 problems may come up when psychodiagnostic instruments are used:

2.2.1 – invitation to the client

2.2.3 – raw data 🡪 the client has the right to access the entire file

2.2.8 – use of psychodiagnostic instruments

2.3.1 – parts of the psychological test report

2.3.4 – rights of the client

Summary Psychodiagnostics GGZ2030

Psychological test = a standardised measure of a sample of behaviour that establishes norms and uses important test items that correspond to what the test is to discover about the test-taker. Is also based on uniformity of procedures in administering and scoring tests.

The standardised measure of a sample of behaviour = an established reference point that a test scorer can use to evaluate, judge, measure against, and compare.

Test items = the questions that a test-taker is asked on any given test.

Uniformity of procedures in administering and scoring of tests = refers to administrators presenting the test in the same way, test-takers taking the test in the same way, and scorers scoring the test the same way every given time that this test is given, taken, and scored 🡪 this helps with:

Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be reproducible but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be reproducible. |

Some of the primary purposes of psychological assessment are to:

disturbance, and capacity for independent living.

recommend forms of intervention and offer guidance about likely outcomes.

identify new issues that may require attention as original concerns are

resolved.

identification of untoward treatment reactions.

in itself.

Although specific rules cannot be developed, provisional guidelines for when assessments are likely to have the greatest utility in general clinical practice can be offered.

3 readily accessible but inappropriate benchmarks can lead to unrealistically high expectations about effect magnitudes:

Instead of relying on unrealistic benchmarks to evaluate findings 🡪 psychologists should be satisfied when they can identify replicated univariate correlations among independently measured constructs.

Therapeutic impact is likely to be greatest when:

Monomethod validity coefficients = are obtained whenever numerical values on a predictor and criterion are completely or largely derived from the same source of information.

Distinctions between psychological testing and psychological assessment:

Distinctions between formal assessment and other sources of clinical information:

Assessment methods:

Clinicians and researchers should recognize the unique strengths and limitations of various assessment methods and harness these qualities to select methods that help them more fully understand the complexity of the individual being evaluated.

Low cross-method correspondence can indicate problems with one or both methods. Cross-method correlations cannot reveal what makes a test distinctive or unique, and they also cannot reveal how good a test is in any specific sense.

Clinicians must not rely on 1 method.

One cannot derive unequivocal clinical conclusions from test scores considered in isolation.

Because most research studies do not use the same type of data that clinicians do when performing an individualised assessment, the validity coefficients from testing research may underestimate the validity of test findings when they are integrated into a systematic and individualised psychological assessment.

Contextual factors play a very large role in determining the final scores obtained on psychological tests, so contextual factors must therefore be considered 🡪 contribute to method variance. However, trying to document the validity of individualised, contextually included conclusions is very complex.

The validity of psychological tests is comparable to the validity of medical tests.

Distinct assessment methods provide unique sources of data 🡪 sole reliance on a clinical interview often leads to an incomplete understanding of patients.

It is argued that optimal knowledge in clinical practice/research is obtained from the sophisticated integration of information derived from a multimethod assessment battery.

Clinical diagnostics is based on 3 elements:

Testing a diagnostic theory requires 5 diagnostic measures:

formulated hypotheses

order to give a clear indication as to when the hypotheses should be accepted

or rejected

the hypotheses have either been accepted or rejected

This results in the diagnostic conclusion.

5 basic questions in clinical psychodiagnostics – classification of requests:

The quantity and type of basic questions to be addressed depends on the questions that were discussed during the application phase. Most requests contain 3 basic questions: recognition, explanation, and indication. In practice, all the basic questions chosen are often examined simultaneously.

Recognition:

Explanation:

Prediction:

Indication:

Evaluation:

Diagnostic cycle = a model for answering questions in a scientifically justified manner:

The diagnostic cycle is a basic diagram for scientific research, not for psychodiagnostic practice.

The diagnostic process:

Critical comments on DTCs:

BDI-II:

Sensitivity = the number of individuals we can correctly diagnose with depression 🡪 from the 100 people receiving a diagnosis, 86 would be diagnosed with depression correctly 🡪 the other 14 individuals are false negatives.

Specificity = the number of individuals we can correctly diagnose as healthy 🡪 from the 100 people receiving a diagnosis, 78 would be diagnosed healthy correctly 🡪 the other 22 individuals are false positives.

The Youden criterion (= sensitivity + specificity) is not always correct 🡪 it may give counterintuitive results in some circumstances.

Based on BDI-II scores alone:

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory is the same as the Self Confidence Test. Narcissists could underreport on psychological tests as they want to do good and won’t show they are suffering from a disease.

Kohut’s self-psychology approach offers the deficit model of narcissism, which asserts that pathological narcissism originates in childhood because of the failure of parents to empathise with their child.

Kernberg’s object relations approach emphasises aggression and conflict in the psychological development of narcissism, focusing on the patient’s aggression towards and envy of others 🡪 conflict model.

Social critical theory (Wolfe) 🡪 narcissism was a result of the collective ego’s defensive response to industrialisation and the changing economic and social structure of society.

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), DSM-V criteria:

or ideal love

DSM-IV mainly focused on the disorder’s grandiose features and did not adequately capture the underlying vulnerability that is evident in many narcissistic individuals.

At least 2 subtypes or phenotypic presentations of pathological narcissism can be differentiated:

defensive and anxious about an underlying sense of shame and inadequacy 🡪 thin-skinned

The former defending the latter: grandiosity conceals underlying vulnerabilities

Both individuals with grandiose and those with vulnerable narcissism share a preoccupation with satisfying their own needs at the expense of the consideration of others.

Pathological narcissism is defined by a fragility in self-regulation, self-esteem, and sense of agency, accompanied by self-protective reactivity and emotional dysregulation.

Grandiose and self-serving behaviours may be understood as enhancing an underlying depleted sense of self and are part of a self-regulatory spectrum of narcissistic personality functioning.

Psychodynamic approaches:

Cognitive-behavioural approaches:

Treatment challenges:

specialness and/or may accentuate feelings of low self-worth, shame and

humiliation.

pharmacological interventions.

The mainstay of treatment for NPD is psychological therapy.

Cronbach’s Alpha = a psychometric statistic

Before Cronbach’s Alpha:

Cronbach’s Alpha is much more general than these two 🡪 it represents the average of all possible split-halves. In addition, it can be used for both dichotomous and continuously scored data/variables.

Coefficient Alpha = Cronbach' Alpha

What is it?:

Cronbach’s Alpha is a coefficient, and it can range from 0.00 to 1.00.

Internal consistency reliability is relevant to composite scores = the sum (or average) of 2 or more scores.

Cronbach’s Alpha measures internal consistency between items on a scale.

The steps needed to generate the relevant output in SPSS:

Interpreting Cronbach’s Alpha output from SPSS:

High Cronbach’s Alpha: suggests that a questionnaire might contain unnecessary duplication of content.

Reliability = how consistently a method measures something.

There are 4 main types of reliability 🡪 each can be estimated by comparing different sets of results produced by the same method.

Test-retest reliability:

Interrater reliability/interobserver reliability:

Parallel forms reliability:

Internal consistency:

Which type of reliability applies to my research?:

Summary types of reliability:

Test-retest reliability The same test over time Measuring a property that you expect to stay the same over time | You devise a questionnaire to measure the IQ of a group of participants (a property that is unlikely to change significantly over time). You administer the test 2 months apart to the same group of people, but the results are significantly different, so the test-retest reliability of the IQ questionnaire is low. |

|---|---|

Interrater reliability/interobserver reliability The same test conducted by different people Multiple researchers making observations or ratings about the same topic | A team of researchers observe the progress of wound healing in patients. To record the stages of healing, rating scales are used, with a set of criteria to assess various aspects of wounds. The results of different researchers assessing the same set of patients are compared, and there is a strong correlation between all sets of results, so the test has high interrater reliability. |

Parallel forms reliability Different versions of a test which are designed to be equivalent Using 2 different tests to measure the same thing | A set of questions is formulated to measure financial risk aversion in a group of respondents. The questions are randomly divided into 2 sets, and the respondents are randomly divided into 2 groups. Both groups take both tests: group A takes test A first, and group B takes test B first. The results of the 2 tests are compared, and the results are almost identical, indicating high parallel forms reliability. |

Internal consistency The individual items of a test Using a multi-item test where all the items are intended to measure the same variable | A group of respondents are presented with a set of statements designed to measure optimistic and pessimistic mindsets. They must rate their agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 to 5. If the test is internally consistent, an optimistic respondent should generally give high ratings to optimism indicators and low ratings to pessimism indicators. The correlation is calculated between all the responses to the “optimistic” statements, but the correlation is very weak. This suggests that the test has low internal consistency. |

Errors of measurement = discrepancies between true ability and measurement of ability

Tests that are relatively free of measurement error: reliable

Tests that have “too much” measurement error: unreliable

Classical test score theory = assumes that each person has a true score that would be obtained if there were no errors in measurement.

3 different distributions shown:

Dispersions around the true score: tell us how much error there is in the measure

Classical test theory assumes that the true score for an individual will not change with repeated applications of the same test 🡪 because of random error, repeated applications of the same test can produce different scores 🡪 random error is responsible for the distribution of scores.

The standard deviation of the distribution of errors for each person tells us about the magnitude of measurement error.

Domain sampling model = considers the problems created by using a limited number of items to represent a larger and more complicated construct 🡪 another central concept in classical test theory.

As the sample gets larger, it represents the domain more and more accurately 🡪 the greater the number of items 🡪 the higher the reliability

Because of sampling error, different random samples of items might give different estimates of the true score: true scores are not available so need to be estimated.

Turning away from classical test theory because it requires that the same test items be administered to each person 🡪 low reliability when few items.

Item response theory (IRT) = the computer is used to focus on the range of item difficulty that helps assess an individual’s ability level.

Difficulties of IRT: requires a bank of items that have been systematically evaluated for level of difficulty 🡪 complex computer software is required and much effort in test development.

Reliability coefficient = the ratio of the variance of the true scores on a test to the variance of the observed scores.

σ2 = describes theoretical values in a population

S2 = values obtained from a sample

If r = .40: 40% of the variation or difference among the people will be explained by real differences among people, and 60% must be ascribed to random or chance factors.

An observed score may differ from a true score for many reasons.

Test reliability is usually estimated in 1 of 3 ways:

Test-retest method:

Parallel forms:

Internal consistency:

Factor analysis = popular method for dealing with the situation in which a test apparently measures several different characteristics.

Difference score = created by subtracting one test from another

Psychologists with behavioural orientations usually prefer not to use psychological tests 🡪 direct observation of behaviour.

2 of 3 ways of measuring this type of reliability:

Standard reliability of a test depends on the situation in which the test will be used:

When a test has an unacceptable low reliability 2 approaches are:

2 approaches to ensure that items measure the same thing:

Low reliability 🡪 findings/correlation not significant 🡪 potential correlations are attenuated, or diminished, by measurement error 🡪 obtained information has no value

Adding more questions to heighten the reliability can be dangerous: it can impact the validity and it takes more time to take the test.

Too high reliability 🡪 remove redundant items/items that do not add anything 🡪 we want some error

Great instruction goes together with a high reliability.

For research rules are less strict than for individual assessment.

The Dutch Committee on Testing (COTAN) of the Dutch Psychological Association (NIP) publishes a book containing ratings of the quality of psychological tests.

The COTAN adopts the information approach, which entails the policy of improving test use and test quality by informing test constructors, test users, and test publishers about the availability, the content, and the quality of tests.

2 key instruments used are:

The 7 criteria of the Dutch Rating System for Test Quality:

Quality of Dutch tests:

Overall picture is positive showing that the quality of the test repertory is gradually improving.

Standards for educational and psychological testing; 3 sections:

Validity = does the test measure what it is supposed to measure?

Validity is the evidence for inferences made about a test score.

3 types of evidence:

Every time we claim that a test score means something different from before, we need a new validity study 🡪 ongoing process.

Subtypes of validity:

Examples of the subtypes of validity:

Face validity Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims? | You create a survey to measure the regularity of people’s dietary habits. You review the survey items, which ask questions about every meal of the day and snacks eaten in between for every day of the week. On its surface, the survey seems like a good representation of what you want to test, so you consider it to have high face validity. |

|---|---|

Content validity Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure? | A mathematics teacher develops an end-of-semester algebra test for her class. The test should cover every form of algebra that was taught in the class. If some types of algebra are left out, then the results may not be an accurate indication of student’s understanding of the subject. Similarly, if she includes questions that are not related to algebra, the results are no longer a valid measure of algebra knowledge. |

Criterion validity Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome that they are designed to measure? | A university professor creates a new test to measure applicants’ English writing ability. To assess how well the test really does measure students’ writing ability, she finds an existing test that is considered a valid measurement of English writing ability and compares the results when the same group of students take both tests. If the outcomes are very similar, the new test has high criterion validity. |

Construct validity Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure? | There is no objective, observable entity called “depression” that we can measure directly. But based on existing psychological research and theory, we can measure depression based on a collection of symptoms and indicators, such as low self-confidence and low energy levels. |

Validity coefficient = correlation that describes the relationship between a test and a criterion 🡪 tells the extent to which the test is valid for making statements about the criterion.

Because not all validity coefficients of .40 have the same meaning, you should watch for several things in evaluating such information 🡪 evaluating validity coefficients:

Relationship between reliability and validity:

The total variation of a test score into different parts:

This example has a validity coefficient of .40.

Assessment of personality relies heavily on self-report measures.

Can people be trusted in what they say about themselves? 🡪 it is preferable to maximize the validity by combining self-report approach with other methods, such as informant reports and observational measures.

Hofstee’s definition of personality: in terms of intersubjective agreement.

Preconceptions: informant methods for personality assessment are time-consuming, expensive, ineffective, and vulnerable to faking or invalid responses.

Still, in daily clinical practice, systematically collecting information from others than the client is not common use. Clinicians generally use interview and observation techniques to determine personality and psychopathology.

Multiple informant information on client personality and psychopathology is not embraced by clinicians.

Level of self-other (dis)agreement:

Moderators of self-other agreement:

Self-assessment in clinical research has most validity.

Most reliable information yielded from assessment of others.

Other studies are based on the assumptions that each of the 2 sources of information yields unique information.

Aggregate ratings by multiple informants correlated higher with observed behaviour than did self-ratings, thus, yielding more accurate information.

Information from others added value when it came to predicting limitations and interpersonal problems, or depressive symptoms and personality characteristics.

We need to examine the content of disagreement.

Reasons for substantial disagreements between couples:

2 hypotheses:

Results:

2 conclusions:

Larger disagreement between self-evaluation and evaluation by someone else: can signal presence of personality pathology as well as a greater risk of dropout.

SCID-5-S: Het gestructureerd klinisch interview voor DSM-5 Syndroomstoornissen

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale

Task 4 – Andrew’s problems become clear

Caldwell: anecdotal interpretation, selectively relating his experiences, without scientific data 🡪 referring to clinical experience to validate his use of a test.

2 traditional reactions on this/him in clinical psychology:

2 extremes 🡪 most of the time it is a mix.

Both empiricists and romanticists base their judgments on a combination of scientific findings, informal observations, and clinical lore 🡪 empiricists place a greater emphasis on scientific findings.

Research supports the empiricist tradition 🡪 it can be surprisingly difficult to learn from informal observations, both because clinicians’ cognitive processes are fallible and because accurate feedback on the validity of judgements is frequently not available in clinical practice. Furthermore, when clinical lore is studied, it is often found to be invalid.

2 new approaches to evaluating the validity of descriptions of personality and psychopathology:

Cognitive heuristics and biases: used to describe how clinical psychologists and other people make judgements.

In conclusion: psychologists should reduce their reliance on informal observations and clinical validation when:

Anchoring = the tendency to fixate on specific features of a presentation too early in the diagnostic process, and to base the likelihood of a particular event on information available at the outset.

Anchoring is closely related to:

Diagnoses can be biased, e.g., by patient (race) and task (dynamic stimuli lacking predictability) characteristics.

Diagnostic anchor = diagnoses suggested in referral letters

In conclusion: referral diagnoses/anchors do seem to influence the correctness of the diagnoses of intermediate but not very experienced clinicians.

Intermediate/moderately experienced clinicians tend to process information distinctively differently 🡪 and perform differently.

Experience brings about a shift: from more deliberate, logical, step-by-step processing to more automatic, intuitive processing 🡪 increased experience = increased tendency to conclude in favour of first impressions.

The present study indicates that the quality of referral information is important, certainly for clinicians with a moderate amount of experience 🡪 when uncertain about the diagnosis it is best to omit a diagnosis instead of giving a wrong “anchor”

Diagnostic errors 🡪 diagnosis with x while disease y 🡪 death

Daniel Kahneman:

We fluidly switch back and forth between these.

Not 2 physically separate systems but represent a model that can help us better understand different ways the brain operates.

When making a diagnosis: system 1 automatically kicks in when we recognize a pattern in a clinical presentation. System 2 requires deliberate thinking 🡪 when not used 🡪 diagnostic errors.

System 1 thinking becomes more accurate as clinicians move through their careers (become more experienced) and it can recognize (more easily) atypical/variant presentations.

Types of cognitive mistakes that can lead to diagnostic errors:

Bayes’ theorem/Bayes’ rule = a formula used to determine the conditional probability of events.

Bayes’ rule is designed to help calculate the posterior probability/post-test probability of an individual’s condition = the probability after the test has been taken and given the outcome of the test.

Based on 3 elements:

Sensitivity = number of individuals correctly diagnosed, the rest are false negatives

Specificity = number of individuals correctly seen as healthy, the rest are false positives

To use Bayes’ rule, it is essential to know: the prevalence of the condition in the population of which the individual is a member 🡪 leads to incorrect conclusions when skipped.

If in a given population a condition is rare (= low prevalence), the probability that the individual has the condition can never be high, even though it is higher with a positive test result than before the test outcome was known.

Different population 🡪 different prevalence of the condition 🡪 same test result leads to a different probability of the same condition

Not following Bayes’ rule properly 🡪 overdiagnosis 🡪 overtreatment

Prev = prevalence/base rate/pre-test probability in the GP’s population

P = probability/likelihood

| = under the condition that/given

D+ = having depression

T+ = positive test result

So, P(D+|T+) means: the probability (P) that the client has a depression (D+) given (|) a positive test result (T+) on a depression questionnaire 🡪 in this case the BDI.

Thus, P(D+|T+) for this client from this GP population is about one third (34%) 🡪 posterior probability/post-test probability

34% is a low probability 🡪 too low for treatment indication

This test (the BDI) cannot be used to establish the presence of depression 🡪 if a clinician is aware of Bayes’ rule, extra diagnostics are needed in addition to administering the BDI.

The calculation is also easy to do with absolute numbers 🡪 steps summarized below.

Positive score: 91/(91+178) = 0,34

Negative score: 712/(19+712). = 0,97 (probability of no depression with a negative score)

Clinicians often forget to include the pre-test probability in their interpretation. If they do look further than the test result, they tend to only consider the sensitivity of a test. Typically, a positive test score is interpreted as the presence of the condition.

Clinicians that are aware of Bayes’ rule 🡪 when interpreting a test, they will take into consideration the setting in which the test was taken and the population to which the tested person belongs 🡪 they will establish the prevalence of the condition in that setting and population.

Sometimes general population, sometimes prevalence in clinicians’ practice or institute is more relevant.

It is recommended to use the information of your own institute or organization about prevalence of a certain disorder or disease.

Ignoring Bayes’ rule = overdiagnosis of conditions with a low pre-test probability (= not prevalent) 🡪 with low prevalence the “no disorder or disorder” group is very large, the post-test probability will remain low even with very high specificity, despite the large numbers of people who have a depression and who tested positive.

Making the error of omitting to take prevalence into account 🡪 major consequences for treatment policy 🡪 and thus for the course of a client’s symptoms.

You should not simply rely on the score of a test. Neither can we rely on the sensitivity and specificity only. Prevalence is also important.

Base rate problem:

12 common biases in forensic neuropsychology 🡪 encountered in evaluation or provision of expert opinions and testimony.

Tackling point: do not take 2 roles at once.

Tackling point: be very careful with getting paid and make clear for what you are being paid.

Tackling point: be critical with forming a professional opinion about the case, do not just say something because you always handle defense cases.

Tackling point: make use of supporting data to form an opinion.

Tackling point: know the prevalence.

Tackling point: know when test scores are abnormal.

Tackling point: treat the diagnostic process with care and always have 2 hypotheses.

Tackling point: be alert for personal and political bias.

Tackling point: analyse interviews to see if there aren’t symptoms that are being missed just because someone is presenting in a certain way.

Tackling point: critically review diagnosis and if possible, conduct your own investigation.

Tackling point: use complete data from the past and after the accident to have a good overview if capabilities were really that impaired.

Tackling point: same as with confirmation bias; make use of the concurrent hypothesis.

Bias will always exist, no matter what. Bias is also unaffected by years of experience in practice.

The diagnosis of mental disorders has 4 major goals:

Giving an accurate diagnosis is important for the correct identification of the problems and the best choice of intervention.

Essential problem in assessment and clinical diagnosis: the neglect of the role of cultural differences on psychopathology.

One way to conceptualize this problem is to use the ethnic validity model in psychotherapy 🡪 the recognition, acceptance, and respect for the presence of communalities and differences in psychosocial development and experiences among people with different ethnic or cultural heritages.

Useful to broaden this to cultural validity = the effectiveness of a measure or the accuracy of a clinical diagnosis to address the existence and importance of essential cultural factors, e.g., values, beliefs, communication patterns.

Problems because of the lack of cultural validity in clinical diagnosis:

Universalist perspective = assumes that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or culture develop along uniform psychological dimensions.

Threats to cultural validity are due to a failure to recognize or a tendency to minimize cultural factors in clinical assessment and diagnosis.

Sources of threats to cultural validity:

In conclusion, cultural factors are important to clinical diagnosis and assessment of psychopathology.

Recommendations to reduce sources of threats to cultural validity:

Bias = nuisance factors in cross-cultural score comparisons

Equivalence = more associated with measurement level issues in cross-cultural score comparisons

Thus, both are associated with different aspects of cross-cultural score comparisons of an instrument 🡪 they do not refer to intrinsic properties of an instrument.

Bias occurs if score differences on the indicators of a particular construct do not correspond to differences in the underlying trait or ability 🡪 e.g., percentage of students knowing that Warsaw is Poland’s capital – geography knowledge.

Inferences based on biased scores are invalid and often do not generalize to other instruments measuring the same underlying trait or ability.

Statements about bias always refer to applications of an instrument in a particular cross-cultural comparison 🡪 an instrument that reveals bias in a comparison of German and Japanese individuals may not show bias in a comparison of German and Danish subjects.

3 types of bias:

The likelihood of a certain type of bias will depend on:

Equivalence = measurement level at which scores can be compared across cultures.

Equivalence of measures (or lack of bias) is a prerequisite for valid comparisons across cultural populations 🡪 can be defined as the opposite of bias.

Hierarchically linked types of equivalence (from small to high):

Bias tends to challenge and can lower the level of equivalence:

An appropriate translation requires: a balanced treatment of psychological, linguistic, and cultural considerations 🡪 translation of psychological instruments involves more than rewriting the text in another language.

2 common procedures to develop a translation:

Remedies: most strategies implicitly assume that bias is a nuisance factor that should be avoided 🡪 there are techniques that enable the reduction and/or elimination of bias.

The most salient techniques for addressing each bias:

Construct bias:

Construct and/or method bias:

Method bias:

Item bias:

Raven’s Progressive Matrices/Raven’s Matrices/RPM = a non-verbal test typically used to measure general human intelligence and abstract reasoning and is regarded as a non-verbal estimate of fluid intelligence = the ability to solve novel reasoning problems and is correlated with several important skills such as comprehension, problem solving, and learning.

All the questions on the Raven’s progressives consist of visual geometric design with a missing piece 🡪 the test taker is given 6 to 8 choices to pick from and fill in the missing piece.

An IQ test item in the style of a Raven’s Progressive Matrices test. Given 8 patterns, the subject must identify the missing 9th pattern.

Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary tests were originally developed for use in research into the genetic and environmental origins of cognitive ability.

The Matrices are available in 3 different forms for participants of different ability:

In addition, "parallel" forms of the standard and coloured progressive matrices were published 🡪 to address the problem of the Raven's Matrices being too well known in the general population.

A revised version of the RSPM – the Standard Progressive Matrices Plus 🡪 based on the "parallel" version but, although the test was the same length, it had more difficult items in order to restore the test's ability to differentiate among more able adolescents and young adults than the original RSPM had when it was first published.

The tests were initially developed for research purposes.

Because of their independence of language and reading and writing skills, and the simplicity of their use and interpretation, they quickly found widespread practical application.

Flynn-effect = intergenerational increase/gains in IQ-scores around the world.

Individuals with ASS score high on Raven’s tests.

Therapeutic assessment (TA):

The client has specific questions 🡪 therapist/assessor tries to answer these questions with test results 🡪 by planning a battery that is in line with the client’s questions.

3 factors that make the change:

Clients who never improved from other treatment(s) do improve from TA.

Power of TA: the basic human need to be seen and understood

A person develops through the process of TA a more coherent, accurate, compassionate, and useful story about themselves.

Therapeutic assessment (TA) = semi-structured approach to assessment that strives to maximize the likelihood of therapeutic change for the client 🡪 an evidence-based approach to positive personal change through psychological assessment.

Development of TA:

Evidence for TA:

Growing number of research 🡪 TA is an effective therapeutic intervention

Ingredients of TA that explain the powerful therapeutic effects:

Steps in the TA process by Finn (and Tonsager):

Traditionally: assessment has focused on gathering accurate data to use in clarifying diagnoses and developing treatment plans.

New approaches: also emphasize the therapeutic effect assessment can have on clients and important others in their lives.

Steps that are not conducted in the traditional psychological assessment: first step, fourth step, seventh step.

Therapeutic assessment (TA) = a collaborative semi-structured approach to individualized clinical (personality) assessment.

psychiatric populations

The therapist and assessor were/are not the same person 🡪 indicating that the techniques practiced by TA providers to foster a therapeutic alliance model transfer to subsequent providers and might aid in treatment readiness and success.

TA can be effective in reducing distress, increasing self-esteem, fostering the therapeutic alliance, and, to a lesser extent, improving indicators of treatment readiness.

On the other hand, symptomatic and functional improvement has yet to be definitively demonstrated with adults.

In children, emerging evidence suggests that TA was associated with symptomatic improvement, but these studies suffer from small samples and nonrandomized designs.

TA has not yet been empirically tested in patients formally diagnosed with personality disorders (PDs) 🡪 present study is a conduction of a pre-treatment RCT among patients with severe personality pathology awaiting an already assigned course of treatment.

2 conditions in the study:

Conclusions:

symptoms and demoralization improvements were observed.

Treatment utility is often defined as improving treatment outcome, typically in terms of short-term symptomatic improvement.

From the more inclusive view of treatment utility however, TA demonstrated stronger ability to prepare, motivate, and inspire the patient for the tasks of therapy, and to provide focus and goals for therapy.

The Netherlands Institute of Psychologists (NIP) is a national professional association promoting the interests of all psychologists. It has its own Code of Ethics = describes the ethical principles and rules that psychologists must observe in practicing their profession.

The objective of the NIP is to ensure psychologists work in accordance with high professional standards, and it guides and support psychologists’ decisions in difficult and challenging situations that they may face.

The Code of Ethics is based on 4 basic principles: responsibility, integrity, respect, and expertise. These basic principles have been elaborated into more specific guidelines.

Psychologists registered with NIP or members need to follow the principles/are obliged to.

It is a good tradition of the NIP to regularly examine the Code of Ethics 🡪 professional ethics are dynamic, so the information is updated regularly.

A Code of Ethics serves several purposes:

Basic principles:

The Dutch Association of Psychologists (NIP) has made a Code of Ethics for Psychologists and the new Guidelines for the Use of Tests 2017.

Psychodiagnostic instruments = instruments for determining someone’s characteristics with a view to making determinations about that person, in the context of advice to that person themselves, or to others about them, in the framework of treatment, development, placement, or selection.

2 problems may come up when psychodiagnostic instruments are used:

2.2.1 – invitation to the client

2.2.3 – raw data 🡪 the client has the right to access the entire file

2.2.8 – use of psychodiagnostic instruments

2.3.1 – parts of the psychological test report

2.3.4 – rights of the client