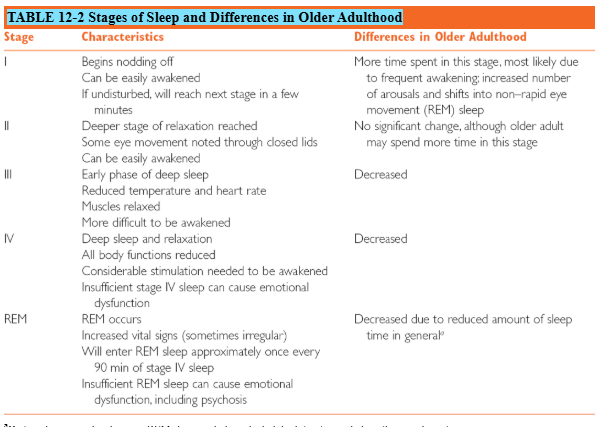

t2

TERMS TO KNOW

Bradykinesias=low movement

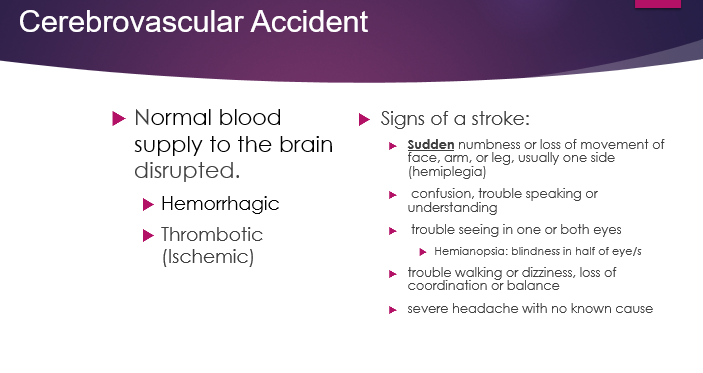

Cerebrovascular accident=stroke; interruption in blood supply to the brain

Dysarthria=difficulty forming words associated with poor muscular control due to damage to the central or peripheral nervous system

Dysphasia=difficulty expressing or comprehending verbal or written language due to brain lesion or injury

Hemiparesis=weakness on one side of the body

Hemiplegia=paralysis on one side of the body

Hemianopsia=decreased vision or blindness in half of one eye or the same half of both eyes

Parkinson’s disease=progressive degeneration of neurons in the basal ganglia resulting in the reduced production of dopamine

Transient ischemic attack (TIA)=temporary or intermittent neurological event that can result from any situation that reduces cerebral circulation

Emotional homeostasis=balance of emotions

Pseudodementia=false appearance of dementia that occurs when persons demonstrate cognitive deficits secondary to being depressed

Substance abuse=inappropriate or excessive use of alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants, tobacco, and other or unknown substances that result in disorders

Delirium=acute confusion, usually reversible

Dementia=irreversible, progressive impairment in cognitive function

Mild cognitive impairment=transitional stage between normal cognitive aging and dementia in which the person has short-term memory impairment and challenges with complex cognitive functions

Sundowner syndrome=nocturnal confusion

Arrhythmia=abnormal heart rate or rhythm

Atherosclerosis=hardening and narrowing of arteries due to plaque buildup in vessel walls

Homans’ sign=pain when the affected leg is dorsiflexed, usually associated with deep phlebitis of the leg

Hypertension=consistent blood pressure reading of ≥130 systolic and/or ≥90 diastolic

Physical deconditioning=decline in cardiovascular function due to physical inactivity

Postural (orthostatic) hypotension=decline in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more after rising and standing for 1 minute

Agnostic=a person who claims not to know with certainty whether or not God exists

Atheist=a person who believes God does not exist

Faith=belief in God, a higher power, or system of religious beliefs

Lack of spiritual well-being=a disruption to the beliefs or practices related to one’s faith or relationship with God or other higher power, causing spiritual needs to be unfulfilled

Religion=human-created structures, rituals, symbolism, and rules for relating to God/higher power

Spirituality=relationship and feelings with that which transcends the physical world

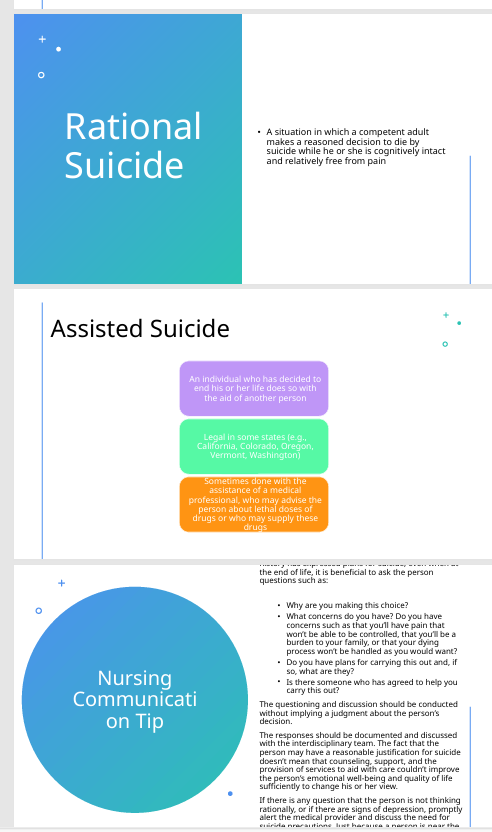

Assisted suicidesuicide committed with the help of another individual

Do not resuscitate (DNR)=medical order advising providers not to initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest

End of life=period when recovery from illness is not expected, death is anticipated, and focus is on comfort

Hospice care=program that delivers palliative care to dying individual and support to dying person and that person’s family and caregivers

Palliative care=care that relieves suffering and provides comfort when cure is not possible

Rational suicide=decision by competent terminally ill person to end his or her life

Consent=granting of permission to have an action taken or procedure performed

Durable power of attorney=allows competent individuals to appoint someone to make decisions on their behalf in the event that they become incompetent

Duty=a relationship between individuals in which one is responsible or has been contracted to provide service for another

HIPAA=Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, assures confidentiality of health information and consumers’ access to their health records

Injury=physical or mental harm to another or violation of a person’s rights resulting from a negligent act

Malpractice=deviation from standard of care

Negligence=failure to conform to the standard of care

Private law=governs relationships between individuals and/or organizations

Public law=governs relationships between private parties and the government

Standard of care=the norm for what a reasonable individual in a similar circumstance would do

Autonomy=to respect individual freedoms, preferences, and rights

Beneficence=to do good for patients

Confidentiality=to respect the privacy

Ethics=a system of moral principles that guides behaviors

Fidelity=to respect our words and duty to patients

Justice=to be fair, treat people equally

Nonmaleficence=to prevent harm to patients

Veracity=truthfulness

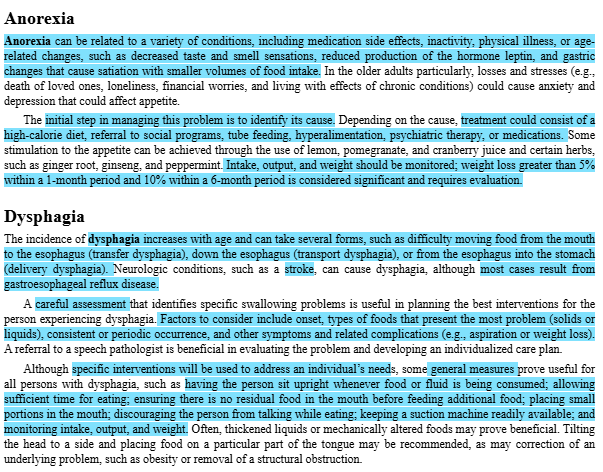

Anorexia=lack of appetite

Cholelithiasis=the formation or presence of gallstones in the gallbladder

Diverticulitis=inflammation or infection of the pouches of intestinal mucosa

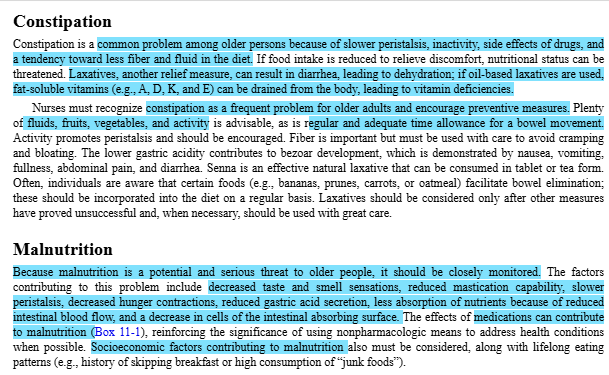

Dysphagia=difficulty swallowing

Esophageal dysphagia=difficulty with the transfer of food down the esophagus

Fecal incontinence=involuntary passage of stool

Flatus=gas in intestinal tract

Gingivitis=inflammation of the gums surrounding the teeth

Hiatal hernia=portion of the stomach protrudes through an opening in the diaphragm

Oropharyngeal dysphagia=difficulty transferring food bolus or liquid from the mouth into the pharynx and esophagus

Periodontal disease=inflammation of the gums extending to the underlying tissues, roots of teeth, and bone

Presbyesophagus=age-related changes to the esophagus causing reduced strength of esophageal contractions and slower transport of food down the esophagus

Established incontinence=involuntary loss of urine that can have an abrupt or sudden onset and is chronic

Functional incontinence=loss of voluntary control of urine due to disabilities that prevent independent toileting, sedation, inaccessible bathroom, medications that impair cognition, or any other factor interfering with the ability to reach a bathroom

Glomerulonephritis=condition in which there is inflammation of the glomeruli, which filter blood as it passes through the kidneys

Mixed incontinence=involuntary loss of urine due to a combination of factors

Neurogenic (reflex) incontinence=loss of control of voiding due to inability to sense the urge to void or control urine flow

Nocturia=voiding at least once during the night

Overflow incontinence=involuntary loss of urine due to an excessive accumulation of urine in the bladder

Stress incontinence=involuntary loss of urine when pressure is placed on the pelvic floor (e.g., from laughing, sneezing, or coughing)

Transient incontinence=involuntary loss of urine that is acute in onset and usually reversible

Urgency incontinence=involuntary loss of urine due to irritation or spasms of the bladder wall that cause a sudden elimination of urine

Urinary incontinence=involuntary loss of urine

Anorexia=loss of appetite

Dysphagia=difficulty swallowing due to difficulty moving food from the mouth to the esophagus (transfer dysphagia), down the esophagus (transport dysphagia), or from the esophagus into the stomach (delivery dysphagia)

Insomniainability to fall sleep, difficulty staying asleep, or premature waking

Nocturnal myoclonus=condition characterized by at least five leg jerks or movements per hour during sleep

Phase advance=falling asleep earlier in the evening and awakening earlier in the morning

Restless legs syndrome=neurological disorder characterized by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs when one lies down

Sleep apnea=disorder in which at least five episodes of cessation of breathing, lasting at least 10 seconds, occur per hour of sleep, accompanied by daytime sleepiness

Sleep latency=delay in the onset of sleep

Chapter 11

List age-related factors that affect dietary requirements in late life.

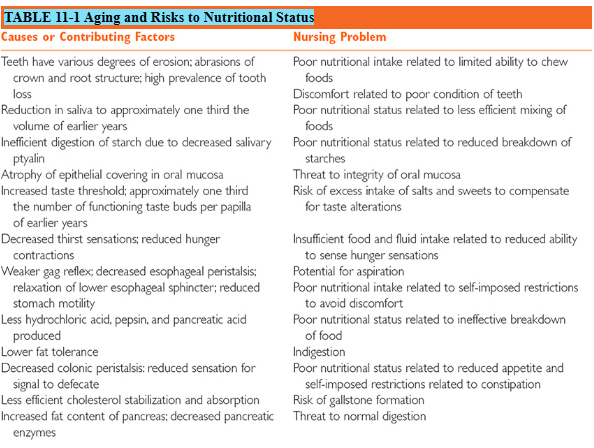

decreased caloric need and decreased metabolic rate among other factors listed in Table 11.1 on p148 in book

Discuss risks to nutritional status in older adults.

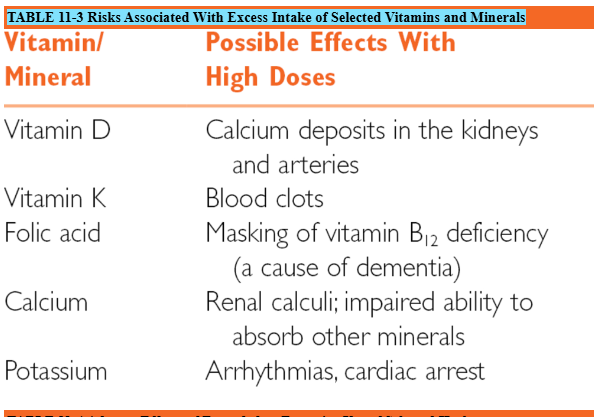

ALSO IN TABLE 11.1Identify risks associated with the use of nutritional supplements.

TABLES 11.3 AND 11.4

Describe the special nutritional needs of aging women.

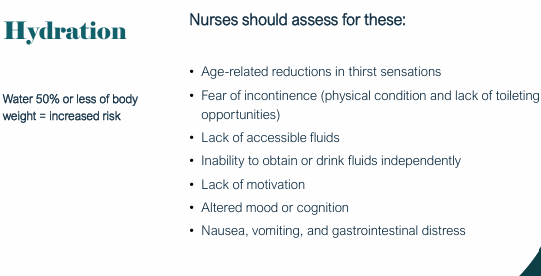

decrease fat and alcohol intake, greater osteoporosis risk (TUMS= great way for quick calcium to help prevent)Describe age-related changes affecting hydration in older adults.

confusion, don’t want to use the restroom, fear, not “in the mood” etc…

Discuss dehydration needs of older adults including: Overview, Causative or contributing factors, Goal, and Interventions

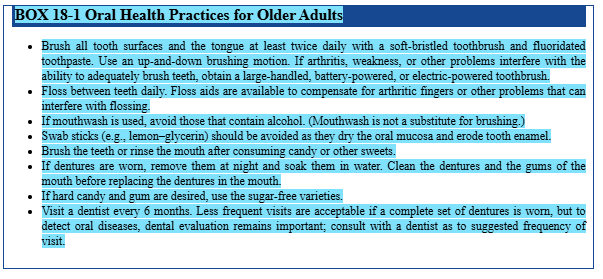

Describe oral health problems that could influence nutritional status

they need to be brushing, recognize periodontal disease, etc

Discuss recommended oral hygiene for older adults.

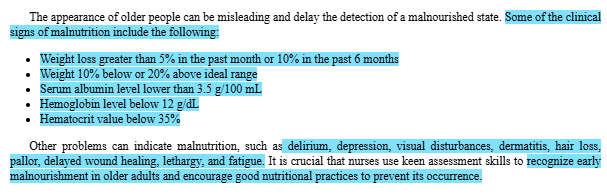

Discuss threats to good nutrition including: Indigestion and Food tolerance, Anorexia, Dysphagia, Constipation, and Malnutrition

REMEMBER TO USE FIBER AND STIMULANTS FOR CHRONIC CONSITPATION… OR AN OSMOTIC LAXITIVE

WATCH THE I&Os!

WEIGHT LOSS…WATCH FOR MORE THAN FIVE PERCENT IN ONE MONTH OR MORE THAN SIX PERCENT IN SIX MONTHSList the clinical signs of malnutrition

WEIGHT LOSS OF MORE THAN FIVE PERCENT IN ONE MONTH OR MORE THAN TEN PERCENT IN SIX MONTHS

WEIGHT DECREASED BY 10 OR 20 PERCENT RANGE

SERUM ALBUMIN LESS THAN 3.5 G/100ML (THINK PROTEIN DEFICIT)

HEMOGLOBIN COUNT BELLOW 12G/DL OR HEMATOCRIT VALUE BELOW 35 PERCENT (THINK IRON DEFICIT)Describe the basic components of the nutritional assessment.

from book:

ASSESSMENT GUIDE 11-1NUTRITIONAL STATUS

HISTORY

Review health history and medical record for evidence of diagnoses or conditions that can alter the purchase, preparation, ingestion, digestion, absorption, or excretion of foods.

Review medications for those that can affect appetite and nutritional state.

Review the type and amount of any nutritional supplements used.

Ask the patient to describe his or her diet, meal pattern, food preferences, and restrictions.

Ask the patient if there has been any change in appetite, digestion, food consumption, or ability to chew or swallow.

Request that the patient keep a diary of all food intake for a week.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Inspect hair. Hair loss or brittleness can be associated with malnutrition.

Inspect skin. Note persistent “goose bumps” (vitamin B6 deficiency), pallor (anemia), purpura (vitamin C deficiency), brownish pigmentation (niacin deficiency), red scaly areas in folds around the eyes and between the nose and corner of the mouth (riboflavin deficiency), dermatitis (zinc deficiency), and fungal infections (hyperglycemia).

Test skin turgor. Skin turgor, although poor in many older adults, tends to be best in the areas over the forehead and sternum; therefore, these are preferred areas to test.

Note muscle tone, strength, and movement. Muscle weakness can be associated with vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Inspect eyes. Ask about changes in vision and night vision problems (vitamin A deficiency). Note the patient’s percentile rank.

Inspect oral cavity. Note dryness (dehydration), lesions, condition of the tongue, breath odor, and condition of teeth or dentures.

Ask about signs and symptoms: sore tongue, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, food distaste, weakness, muscle cramps, burning sensations, dizziness, drowsiness, bone pain, sore joints, recurrent boils, dyspnea, dysphagia, anorexia, and appetite changes.

Observe person drinking or eating for difficulties.

Biochemical Evaluation

Obtain blood sample for screening of total iron binding capacity, transferrin saturation, protein, albumin, hemoglobin, hematocrit, electrolytes, vitamins, and prothrombin time.

Obtain urine sample for screening of specific gravity.

Anthropometric Measurement

Measure and ask about changes in height and weight. Use age-adjusted weight chart for evaluating weight. Note weight losses of 5% within the past 1 month and 10% with the past 6 months.

Determine triceps skinfold measurement (TSM). To do so, grasp a fold of skin and subcutaneous fat halfway between the shoulder and elbow and measure with a caliper. Note the patient’s percentile rank.

Measure the midarm circumference (MC) with a tape measure (using centimeters) and use this to calculate midarm muscle circumference (MMC) with the formula:

The standard MMC is 25.3 cm for men and 23.2 cm for women. MMC below 90% of the standard is considered undernutrition; below 60% is considered protein–calorie malnutrition.

PSYCHOLOGICAL EXAMINATION

Test cognitive function.

Note alterations in mood, behavior, cognition, and level of consciousness. Be alert to signs of depression (can be associated with deficiencies of vitamin B6, magnesium, or niacin).

Ask about changes in mood or cognition.

Chapter 12

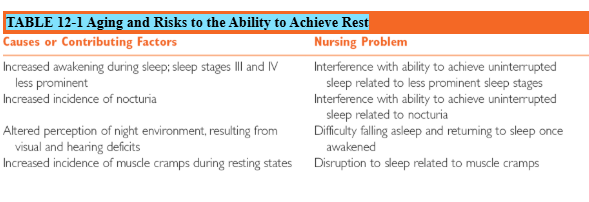

Identify the characteristics and differences in each stage of sleep in older adulthood.

MORE TIME IN STAGE ONE AND TWO WITH LESS TIME IN THREE AND FOUR/REM SLEEP WHICH ALSO LEADS TO MORE AWAKENING DURING SLEEP BECAUSE LESS DEEP

Circadian Sleep–Wake CyclesOlder adults are more likely to fall asleep earlier in the evening and awaken earlier in the morning, a behavior referred to as phase advance . The quantity of sleep does not change, but the hours in which it occurs may. This change can prove frustrating for older adults who find themselves nodding off during evening activities and wide awake in the early morning hours when everyone else is asleep. In addition, daytime naps may be needed to compensate for reductions in nighttime sleep. Adjusting schedules to accommodate the altered biorhythms could prove useful. Increasing natural light is also useful in pushing the circadian rhythm toward a later hour of sleep.

Describe the following sleep disturbances:

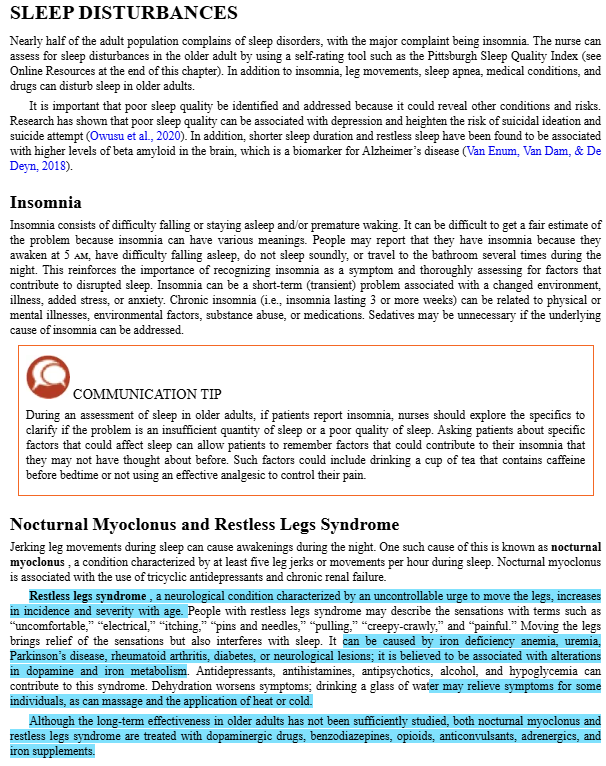

Insomnia

Nocturnal myoclonus

Phase advance: more likely to fall asleep earlier in the evening and awaken earlier in the morning, a behavior referred to as phase advance .

Restless legs syndrome

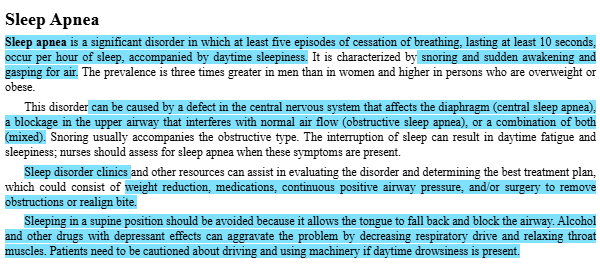

Sleep apnea

Sleep latency

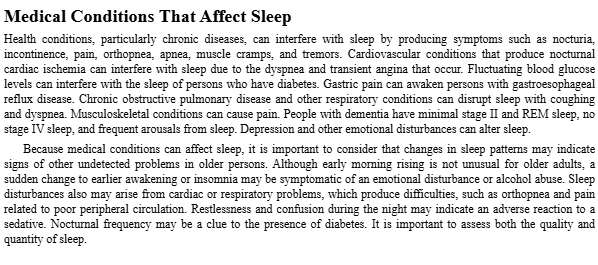

3. Describe medical conditions that may affect sleep in older adults.

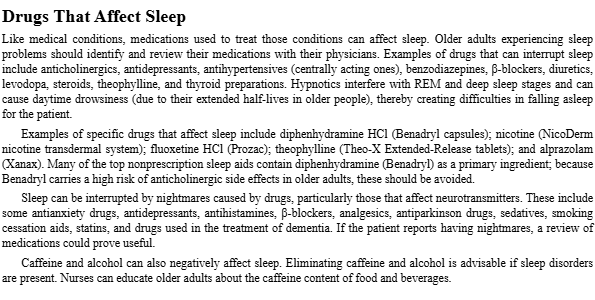

4. Identify drugs that affect sleep in older adults.

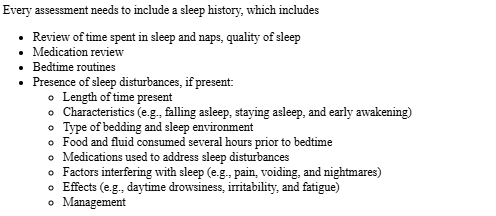

Discuss what is included in a sleep history.

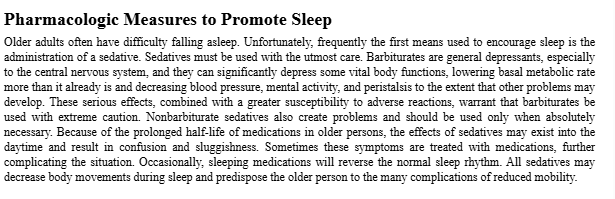

Describe pharmacological measures to promote sleep.

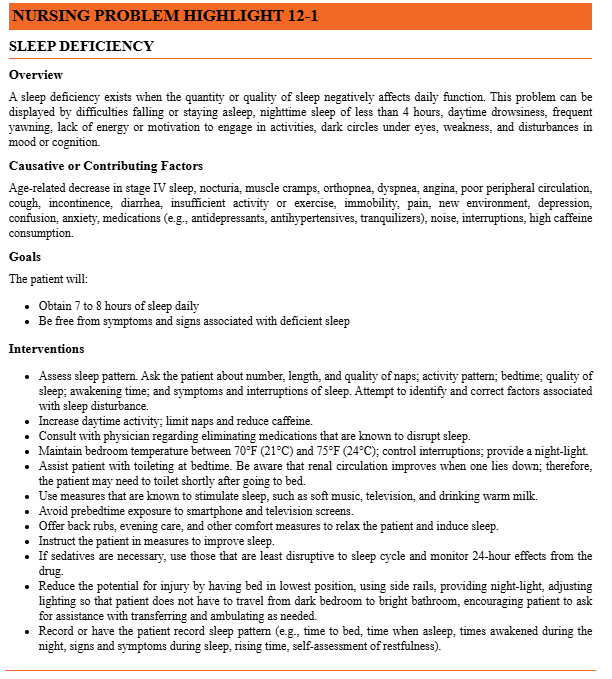

Discuss Sleep deficiency including:

Causative or contributing factors

Goals

Interventions

Identify non-pharmacological measures to promote sleep.

Activity and rest schedules

Environment

Food and supplements

Stress management

Discuss compensatory measures for stress control.

Chapter 8:

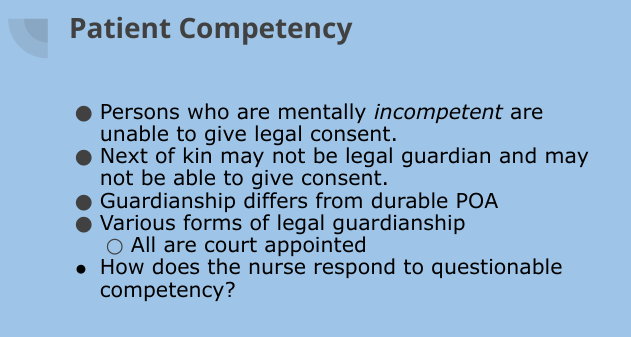

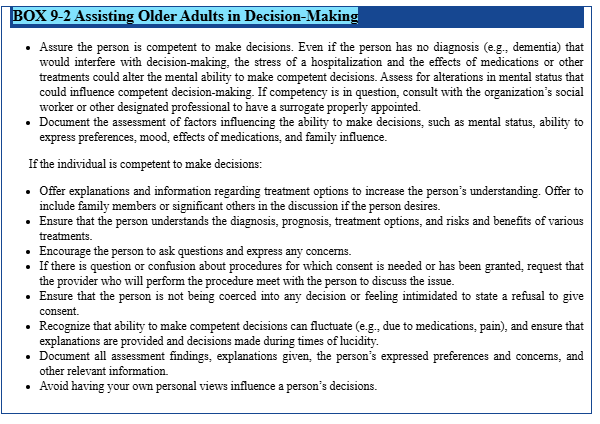

Define these terms: patient competency, guardianship, durable power of attorney, DNR, elder abuse, and neglectful injury

Describe the importance of patient competency and nursing actions when it is questionable.

LOOK FOR QUESTIONABLE SIGNS, MAKE SURE TO BE AN ADVOCATE, ASK ABOUT POA AND IF ITS DURABLE, WE DON’T DETERMINE, CONTACT THE FAMILY ESPECIALLY ABOUT POA OR GUARDIANSHIP, GO TO THE PROVIDER

Differentiate between guardianship and durable power of attorney.

Describe what do not resuscitate means.

NO NOT RECECITATE= DNR ORDER, MAKE SURE TO EDUCATE PATIENT ON AND ALLOW FOR THEIR OWN INFORMED DECESION, MUST BE FROM THE PROVIDER

List 3 reasons why an older adult may choose a DNR order.

RELIGOUS REASONS? HAVE SOMETHING THAT WOULD CAUSE MORE HARM TO THE PATIENT IF RECECITATED THAN IF NOT, ETCDescribe types of elder abuse and indications of possible abuse or neglect during routine interactions with older adult patients.

WE ARE MANDADATED REPORTERS, BE ON THE LOOKOUT FOR THE S/S OF ELDER ABUSE LISTED BELOW

Chapter 8: Legal and Ethical Considerations in Geriatric CareDefinitions

Patient Competency: The ability of a patient to make lawful decisions. This is assessed by providers; nurses advocate for autonomy when capacity is questionable.

Guardianship: A legal status where a court-appointed individual is authorized to make decisions for an incompetent older adult, typically involving legal proceedings.

Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA): A legal document designating someone (an agent) to act on another's behalf, which remains in effect even if the principal becomes incompetent.

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR): A medical order indicating that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should not be attempted if the patient’s heart stops or they stop breathing.

Elder Abuse: A real and multifaceted issue that includes physical, emotional/psychological, sexual, and financial exploitation, neglect, abandonment, and self-neglect.

Neglectful Injury: This term implies harm resulting from neglect, a type of elder abuse characterized by failing to provide for an older adult's basic needs (e.g., food, hydration, hygiene, medical care), leading to physical or emotional harm or risk of harm.

Importance of Patient Competency and Nursing Actions When Questionable

Importance: Respect for patient freedoms, preferences, and rights (autonomy) is paramount. Competency ensures that decisions made reflect the patient's true wishes and values.

Nursing Actions When Questionable:

Nurses do not determine competency; providers assess capacity and document these assessments.

Advocate for patient autonomy.

Involve providers and legal teams; seek evaluations.

Involve family and potentially initiate guardianship or Power of Attorney (POA) processes.

Ensure informed consent processes are followed, especially when decision-making capacity is unclear.

Differentiating Between Guardianship and Durable Power of Attorney

Guardianship:

Court-appointed process.

Typically used when the person cannot make lawful decisions.

Involves legal proceedings and a public record.

Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA):

A legal document (usually drafted by an attorney) designating an agent to act on another’s behalf.

Remains in effect when the principal becomes incompetent.

An administrative/legal document outside of court unless contested.

Preferred for ongoing representation of older adults who lose decision-making capacity.

Meaning of Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) Order

A DNR order is a medical instruction specifying that CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) should not be performed if a patient's heart stops beating or they stop breathing.

It is a specific medical order, not a cessation of all care.

Requires provider involvement and patient or patient representative consent.

Documentation and identification (e.g., labeled charts, wristbands, room signs) are crucial.

In home settings, a DNR or living will should be easily accessible for EMS.

Reasons for Choosing a DNR Order

Older adults may choose a DNR order to:Maintain quality of life: Prioritize comfort and dignity in end-of-life care over aggressive medical interventions.

Avoid unwanted invasive procedures: Prevent interventions like chest compressions, intubation, or defibrillation that may be painful, prolong suffering, or cause further decline without a meaningful benefit.

Respect personal autonomy and values: Exercise their right to self-determination regarding medical treatment decisions, aligning medical care with their personal beliefs about life and death.

Types of Elder Abuse and Indications of Possible Abuse or Neglect

Types of Elder Abuse:

Physical abuse: Intentional use of physical force that results in bodily injury, pain, or impairment.

Emotional/psychological abuse: Infliction of anguish, pain, or distress through verbal or nonverbal acts (e.g., intimidating, humiliating, threatening).

Sexual abuse: Nonconsensual sexual contact of any kind with an older adult.

Exploitation: Illegal or improper use of an older adult's funds, property, or assets.

Neglect: Failure to provide for the older adult's basic needs (e.g., food, water, medicine, clothing, shelter, personal safety, hygiene).

Abandonment: Desertion of an older adult by a person who has assumed responsibility for their care.

Self-neglect: An older adult's behaviors that threaten their own health or safety, often due to physical or mental impairment.

Indications of Possible Abuse or Neglect During Routine Interactions:

Delay in seeking medical care for serious conditions.

Malnutrition and dehydration without an apparent medical cause.

Unexplained bruising, poor hygiene, or inadequate grooming.

Inappropriate administration of medications (e.g., over-sedation).

Recurrent UTIs or other infections without clear medical cause.

Strong urine odor, bed sores, or other physical signs of neglect (e.g., soiled clothing/bedding).

Social isolation or loneliness, which can be a form of neglect or self-neglect if it leads to harm.

Unexplained financial strain or sudden changes in financial status.

Caregiver stress or reluctance to leave the older adult alone with others.

Chapter 9:

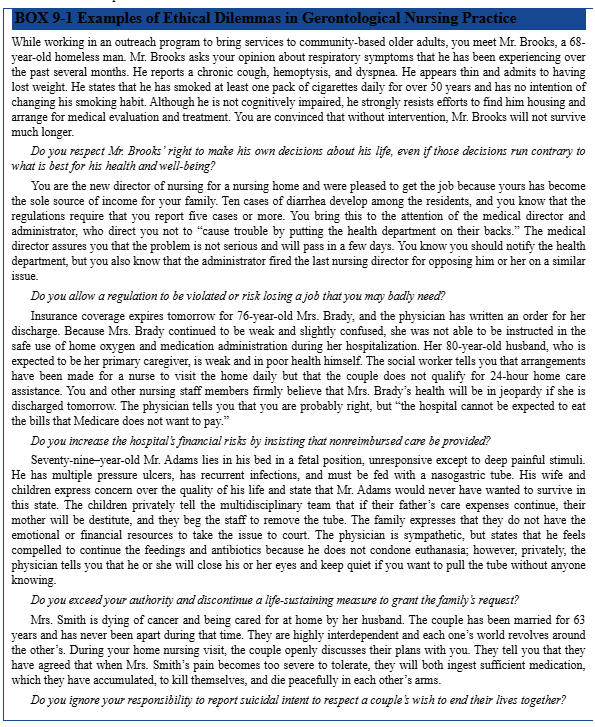

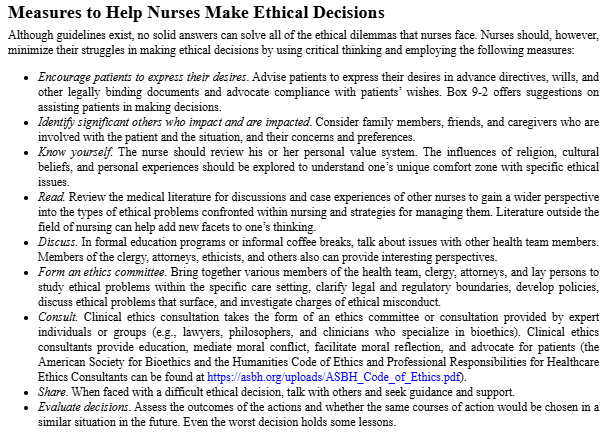

Evaluate an ethical dilemma (p. 127) using measures to help nurses make ethical decisions.

Chapter 9: Ethical Decision-MakingEvaluating an Ethical Dilemma Using Measures to Help Nurses Make Ethical Decisions (Case Scenario Example) When evaluating an ethical dilemma, such as the case of Mr. J (referred to by the full note), nurses should employ a structured decision-making process:

Nurse's Role: Be impartial, provide comprehensive information, support patient autonomy, and assess for financial and social implications related to the decision.

Considerations:

Financial Impact: How will the decision affect the patient's and spouse's financial well-being?

Patient and Spouse Values: Understand and respect the core values and preferences of both the patient and their significant other.

Potential Conflicts: Identify any disagreements or conflicts of interest among patient, family, and healthcare team.

Need for Additional Information: Gather all relevant medical evidence, explore alternative options, and consult with other professionals (e.g., social work, ethics committee).

Possible Actions:

Facilitate open and honest discussion among all parties involved.

Obtain more information or clarification from healthcare providers and other resources.

Refer to appropriate counseling (e.g., financial, ethical, spiritual).

Involve family members in a constructive manner, ensuring their understanding.

Protect the rights of both the patient and the spouse, ensuring informed consent and shared decision-making.

Document all discussions, assessments, interventions, and decisions thoroughly.

Important Attitude: Maintain self-awareness and emotional regulation. Recognize personal biases and values to ensure professional conduct and impartial care delivery.

Chapter 18:

Analyze aging-related changes and their effects on gastrointestinal health by creating a summary table.

Educate a simulated patient about GI health promotion, highlighting what you consider to be the top 3 must-dos to maintain proper GI function.

FLUID, FIBER, AND ACTIVITY!!! REMMEBER TO CHEW! KEEP UP WITH PROPER ORAL CARE!

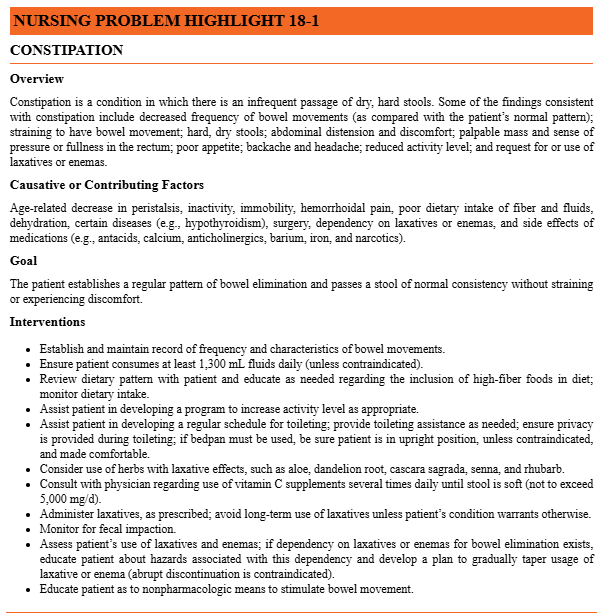

Discuss causative and contributing factors that can lead to chronic constipation in older adults.

Explain the nursing management, including interventions, for an older adult with chronic constipation.

Chapter 18: Gastrointestinal Health in Older Adults

Aging-Related Changes and Their Effects on Gastrointestinal Health: Summary Table

GI System Component | Age-Related Change | Effects on GI Health |

|---|---|---|

Oral Cavity/Pharynx | Tissue atrophy, decreased saliva production, decreased taste/smell, decreased chewing efficiency | Difficulty chewing and swallowing (dysphagia), altered nutrition, reduced appetite, increased risk of aspiration. |

Esophagus | Decreased motility, decreased lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure | Increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) and heartburn. |

Stomach | Gastric mucosal atrophy, decreased blood flow, changes in acid production | Impaired digestion and absorption of nutrients (e.g., B12, iron), increased risk of gastritis. |

Small Intestine | Decreased digestive enzyme secretions, decreased motility, slower transit time | Reduced nutrient absorption, increased risk of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. |

Large Intestine | Decreased motility, changes in nerve supply and muscle tone, longer transit time, decreased sensation to defecate | Increased risk of constipation, fecal impaction, and diverticular disease. |

Liver | Shrinks in size, reduced regenerative capacity, decreased protein synthesis | Altered drug metabolism (pharmacokinetics), reduced capacity to recover from injury. |

General GI Function | Dehydration, decreased physical activity | Worsened GI function and motility, increased constipation. |

GI Health Promotion: Top 3 Must-Dos

For a simulated patient, the top 3 must-dos to maintain proper GI function are:Consume adequate fiber: A high-fiber diet (fruits, vegetables, whole grains) is crucial for maintaining regular bowel movements and promoting gut health.

Ensure adequate fluid intake: Hydration is essential to keep stool soft and prevent constipation. Recommend drinking water throughout the day.

Engage in regular physical activity: Movement increases GI motility, helping to prevent constipation and promote overall digestive health.

Causative and Contributing Factors to Chronic Constipation in Older Adults

Chronic constipation in older adults is a common problem with multiple contributing factors:Decreased GI Motility: Age-related slowing of the large intestine and colon transit time.

Dehydration: Insufficient fluid intake leads to harder, drier stools.

Polypharmacy: Many medications commonly used by older adults (e.g., opioids, anticholinergics, iron supplements, calcium channel blockers, diuretics) can cause constipation as a side effect.

Dietary Factors: Low fiber intake and poor nutritional choices.

Inactivity/Immobility: Lack of physical activity reduces bowel stimulation.

Dental Issues: Poor dentition or ill-fitting dentures can make chewing difficult, leading to a reduced intake of fiber-rich foods.

Underlying Medical Conditions: Conditions like hypothyroidism, diabetes, neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson's), and strictures can contribute.

Ignoring the Urge to Defecate: Suppressing the urge due to pain, inconvenience, or lack of privacy can lead to stool hardening.

Nursing Management and Interventions for Chronic Constipation

Nursing management for older adults with chronic constipation includes:Assessment: Regularly assess bowel movements. Inquire about stool frequency, consistency, and any straining. Screen for signs of fecal impaction (hard stool with leakage of liquid stool around it).

Non-Pharmacologic Interventions (First-Line):

Increase Fiber: Educate on high-fiber foods; consider fiber supplements if dietary intake is insufficient.

Increase Fluids: Encourage adequate hydration throughout the day.

Increase Physical Activity: Promote mobility and exercise suitable for the patient's capabilities.

Regular Toilet Scheduling: Establish a consistent time for toileting, ideally after meals, leveraging the gastrocolic reflex.

Positioning: Ensure proper positioning for defecation to facilitate bowel emptying.

Pharmacologic Interventions (Cautious Use):

Use laxatives and stool softeners judiciously; educate on appropriate use to avoid dependence.

Consider bulk-forming agents, osmotic laxatives, or stimulants as prescribed.

Avoid soap suds enemas in older adults; consider other types (e.g., saline, mineral oil).

Review polypharmacy to identify and potentially deprescribe constipation-inducing medications in collaboration with the healthcare team.

Probiotics/Prebiotics: Discuss the potential role of these in maintaining gut flora.

Patient Education: Provide non-judgmental education on bowel health, prevention strategies, and when to seek medical attention.

Safety: Emphasize safe practices around rectal stimulation if necessary, highlighting the risks of unsafe techniques.

Collaboration: Coordinate with dietitians, pharmacists, and physicians to optimize management plans.

Chapter 19:

Analyze aging-related changes and their effects on urinary elimination by creating a summary table.

URINARY FREQUENCY… RESULT OF NORMAL PROCESSES OF AGING

Educate a simulated patient about urinary system health promotion, highlighting what you consider to be the top 3 must-dos to maintain proper GI function.

Define these terms: Urinary incontinence, transient incontinence, established incontinence, stress incontinence, urgency incontinence, overflow incontinence, neurogenic incontinence, functional incontinence, and mixed incontinence.

Explain the nursing management, including assessment, goals, and nursing actions, for an older adult with urinary incontinence.

Chapter 19: Urinary System and Incontinence in Older AdultsAging-Related Changes and Their Effects on Urinary Elimination: Summary Table

Urinary System Component

Age-Related Change

Effects on Urinary Elimination

Bladder

Decreased bladder capacity

Increased frequency of urination, particularly nocturia.

Bladder Control

Increased involuntary contractions (bladder spasms)

Higher urge to urinate, leading to urgency.

Women (Estrogen Decline)

Thinning of urethral mucosa, altered pelvic floor muscle tone

Contributes to urinary urgency, frequency, and stress incontinence.

Men (Prostate)

Prostate enlargement (BPH)

Obstruction of urine flow, leading to urgency, frequency, weak stream, incomplete emptying.

Kidneys

Reduced size, fewer nephrons, decreased mass, decreased GFR

Decreased renal clearance, affecting drug handling and increasing sensitivity to nephrotoxic agents.

Nocturnal Urine Production

Increases

More common nocturia (waking to urinate at night).

Urinary System Health Promotion: Top 3 Must-Dos

For a simulated patient, the top 3 must-dos to maintain proper urinary function are:Maintain adequate hydration: Drink sufficient fluids throughout the day to keep urine dilute and flush the urinary system, but avoid excessive intake close to bedtime to minimize nocturia.

Practice regular toileting and bladder training: Establish a routine for voiding, and for those with urge symptoms, gradually increase the time between voids to help retrain the bladder.

Perform pelvic floor muscle exercises (Kegels): These exercises strengthen the muscles that support the bladder and urethra, which is particularly beneficial for stress incontinence and overall bladder control.

Definitions of Urinary Incontinence Types

Urinary incontinence is not an expected age-related change; it is a disease/disorder that requires investigation and treatment.Urinary Incontinence (UI): Involuntary leakage of urine.

Transient Incontinence: Acute, temporary, and reversible episodes of incontinence, often caused by temporary factors such as infection, medications, or delirium. (Not explicitly defined in the provided notes but inferred as temporary).

Established Incontinence: Chronic or persistent incontinence, often linked to underlying genitourinary or neurological conditions. (Not explicitly defined in the provided notes but inferred as chronic).

Urge Incontinence: Involuntary urine loss accompanied by a sudden, strong desire to void (urgency); often linked to an overactive bladder.

Stress Incontinence: Involuntary urine leakage with physical exertion, such as coughing, laughing, sneezing, or lifting.

Overflow Incontinence: Leakage of urine from an overly full bladder, often due to urethral obstruction or weakened bladder muscles, resulting in constant dribbling.

Neurogenic (Reflex) Incontinence: Involuntary urine loss due to central nervous system or peripheral nerve damage, leading to an inability to sense urgency or control flow.

Functional Incontinence: Incontinence caused by functional barriers to reaching the toilet (e.g., mobility limits, cognitive impairment, environmental barriers), rather than a primary urinary tract problem.

Mixed Incontinence: A combination of two or more types of incontinence, most commonly urge and stress incontinence.

Nursing Management for an Older Adult with Urinary Incontinence

Nursing management follows the nursing process, including assessment, goal setting, and interventions:Assessment:

Gather a thorough history: prostate status (men), prior radiation, estrogen therapy or replacement (women), pelvic floor integrity, and current medications (especially anticholinergics).

Perform a Post-Void Residual (PVR) measurement using a bladder scanner (PVR > 100\,mL often indicates overflow incontinence).

Conduct a urinalysis to check for infection, blood, or other abnormalities.

Evaluate for functional barriers: assess mobility, bathroom accessibility, caregiver support, and cognitive status.

Goals:

Reduce incontinence episodes.

Improve bladder control and capacity.

Enhance quality of life and dignity.

Prevent complications such as skin breakdown and UTIs.

Nursing Actions (Interventions):

Distinguish Incontinence Types: Tailor interventions based on the specific type(s) of incontinence (urge, overflow, functional, mixed).

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT): Teach Kegel exercises and refer to physical therapy for stress incontinence.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Fluid management: Ensure adequate hydration but manage timing (e.g., reduce intake before bed).

Caffeine and alcohol reduction: These can irritate the bladder.

Weight management: Reduces pressure on the bladder and pelvic floor.

Constipation management: Address constipation as it can worsen urinary symptoms.

Bladder Training and Scheduled Voiding: For neurogenic or functional incontinence, implement scheduled toileting and prompt prompts for cognitively impaired individuals. Gradually increase voiding intervals for urge incontinence.

Pharmacologic Considerations: Educate patients about prescribed medications and monitor for side effects; collaborate with the healthcare team to optimize regimens and consider deprescribing anticholinergics when possible.

Environmental and Caregiving Strategies: Remove barriers to bathroom access, ensure assistive devices are within reach, provide appropriate toileting equipment.

Avoid Routine Catheterization: Minimize catheter-associated infections; educate about when catheterization is necessary.

Patient Education: Provide information on incontinence causes, management strategies, and prevention.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Work with physical therapists, dietitians, and social workers to provide comprehensive care.

Chapter 30

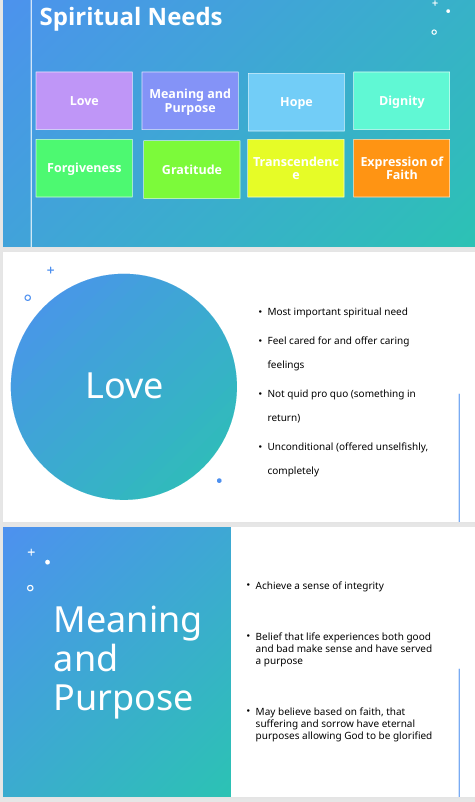

1. Differentiate between spirituality and religion in the context of holistic nursing care.

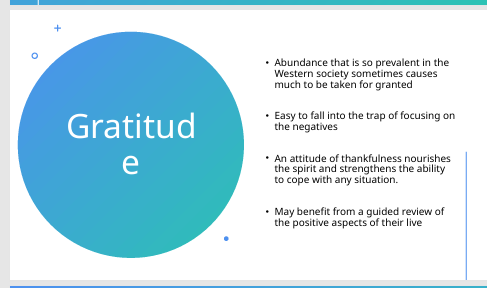

2. Discuss common spiritual needs of older adults, including love, purpose, hope, dignity, forgiveness, gratitude, transcendence, and faith.

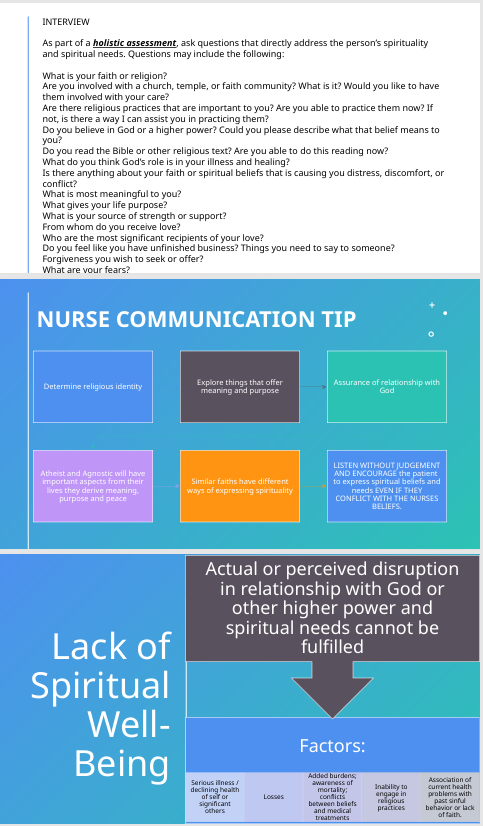

3. Conduct a basic spiritual assessment by exploring patients’ faith beliefs, practices, and community affiliations.

4. Demonstrate respect for and support of patients’ spiritual beliefs by providing opportunities for expression, promoting hope, and assisting in finding meaning in challenging circumstances.

Chapter 36

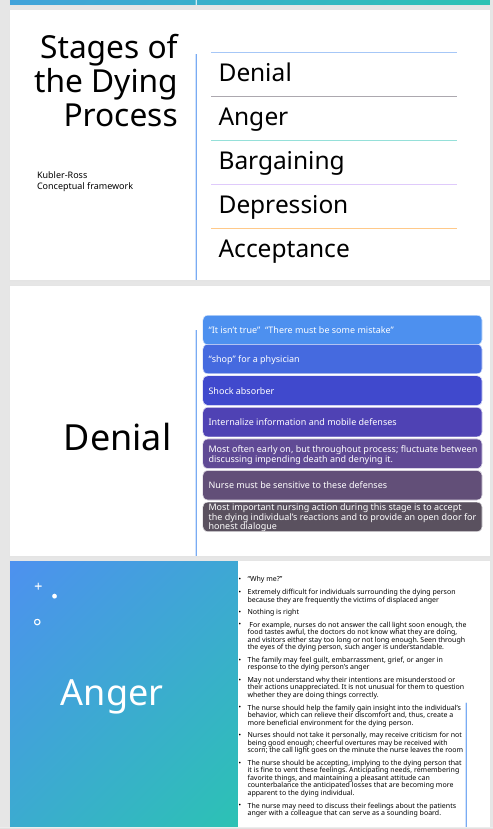

5. Explain the role of the gerontological nurse in providing holistic support—physical, emotional, and spiritual—during the dying process.

6. Describe the stages of the dying process.

7. Apply the Kübler-Ross framework to identify appropriate nursing interventions for patients at different stages of the dying process.

8. Discuss ethical considerations related to rational suicide and assisted suicide, including the importance of assessment, counseling, and supportive care.

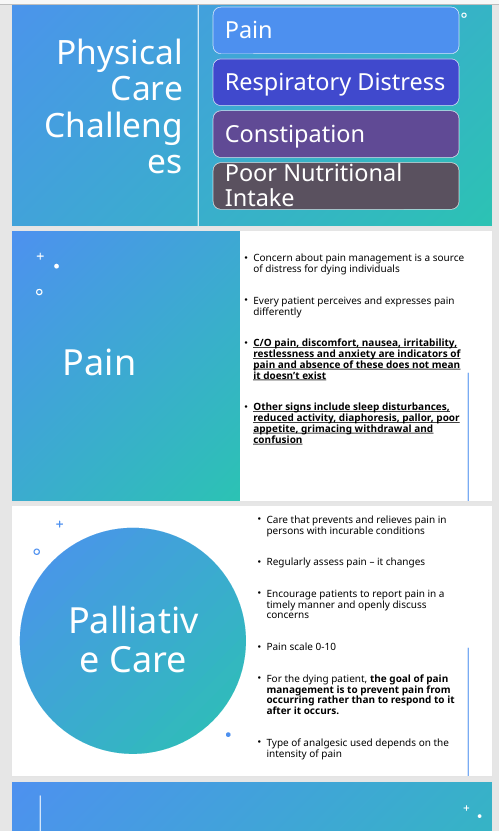

9. Identify common physical signs and symptoms that occur as death approaches including pain, respiratory distress, constipation, poor nutritional intake.

10. Identify appropriate nursing interventions for comfort and dignity.

11. Discuss strategies to support family, friends, and healthcare staff experiencing grief associated with the dying process.

Chapter 17

12. Describe common age-related changes in the cardiovascular system of older adults.

13. Recognize the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in women.

14. Explain lifestyle practices that promote cardiovascular health in later life.

15. Discuss the following cardiovascular conditions including cues (signs and symptoms), risk factors, management for:

1. Hypertension (HTN)

2. Hypotension

3. Congestive heart failure (CHF)

4. Pulmonary emboli (PE)

5. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

6. Angina

7. Myocardial infarction

8. Hyperlipidemia

9. Arrhythmias

10. Atrial Fibrillation

11. Peripheral Vascular Disease

12. Arteriosclerosis

13. Diabetic problems

14. Aneurysms

15. Varicose Veins

16. Venous thromboembolism

16. Identify risk factors for pulmonary emboli in older adults.

17. Explain how atypical presentations can delay diagnosis.

18. Recognize that most adults over 70 have some degree of coronary artery disease.

19. Discuss atrial fibrillation as the most common sustained arrhythmia in older adults.

20. Identify the major contributing factor to ischemic stroke.

21. Differentiate between atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis in older adults.

22. Discuss ways to promote circulation.

23. Discuss foot care for persons with peripheral vascular disease.

24. Describe complications of vascular changes, including varicosities, falls, ulcerations, and infections.

25. Apply nursing interventions to promote cardiovascular health in older adults.

Chapter 30: Spirituality in Holistic Nursing Care

Differentiate between spirituality and religion in the context of holistic nursing care.

Spirituality: The relationship and feelings that connect humans to the divine, transcending the physical world.

Religion: A human-constructed system describing structures, rituals, and rules for relating to God or a higher power.

Nursing focus: Supporting spirituality and meaning, not converting beliefs.

Discuss common spiritual needs of older adults, including love, purpose, hope, dignity, forgiveness, gratitude, transcendence, and faith.

Meaning and purpose: Supported by Erik Erikson’s theory, achieving integrity in late life is aided by a spiritual need for meaning and purpose; helps individuals believe in the future and stay committed to their beliefs even when facing pain or adversity.

Hope: A spiritual need that helps people believe in the future and remain committed to those who suffer.

Most important spiritual need: Unconditional [need], suggesting unconditional acceptance or love.

Conduct a basic spiritual assessment by exploring patients’ faith beliefs, practices, and community affiliations.

Spiritual assessment: Distinguishing between assessing spirituality and interventions to support spiritual practices.

Visible cues of spirituality: Physical or symbolic signs (e.g., rosary or Bible present) that indicate spiritual practice or needs.

Demonstrate respect for and support of patients’ spiritual beliefs by providing opportunities for expression, promoting hope, and assisting in finding meaning in challenging circumstances.

Core nurse goal in spiritual care: Not conversion, but helping the patient discuss spiritual issues and maintain practices.

Interventions: Respect rituals, provide scripture, arrange clergy support, facilitate discussions on spiritual issues, and accommodate patient practices.

Providing uninterrupted time for prayer/reflection/meditation: An aspect of honoring solitude.

Supporting spirituality can enhance health and healing.

Chapter 36: End-of-Life Care

Explain the role of the gerontological nurse in providing holistic support—physical, emotional, and spiritual—during the dying process.

Nurse’s broad goals: Ensure comfort, support meaning and dignity, and respect patient and family wishes.

Physical support: Nonpharmacologic end-of-life pain or comfort measures (e.g., massage, acupuncture).

Spiritual support: Meeting spiritual needs can support health and healing even near end of life; provide uninterrupted time for prayer/reflection/meditation.

Emotional support: Supporting open expression of grief, providing follow-up support groups, and advocating for consumer protection in funeral decisions (e.g., avoiding coercive or costly funeral expenses).

Describe the stages of the dying process.

No specific stages of dying are described in the provided notes.

Apply the Kübler-Ross framework to identify appropriate nursing interventions for patients at different stages of the dying process.

The Kübler-Ross framework is not discussed in terms of application or interventions in the provided notes.

Discuss ethical considerations related to rational suicide and assisted suicide, including the importance of assessment, counseling, and supportive care.

Not covered in the provided notes.

Identify common physical signs and symptoms that occur as death approaches including pain, respiratory distress, constipation, poor nutritional intake.

The notes only mention "pain or comfort measures" in end-of-life care, without explicitly listing common physical signs of approaching death.

Identify appropriate nursing interventions for comfort and dignity.

Interventions: Provide nonpharmacologic pain or comfort measures (e.g., massage, acupuncture).

Patient-centered care: Provide uninterrupted time for prayer/reflection/meditation, avoid pressuring patients, and support their rituals.

Care planning should include honoring viewing preferences, open expression of grief, follow-up support groups, and consumer protection in funeral decisions.

Discuss strategies to support family, friends, and healthcare staff experiencing grief associated with the dying process.

Strategies: Provide follow-up support groups and resources for bereavement.

Chapter 17: Cardiovascular System in Older Adults

Describe common age-related changes in the cardiovascular system of older adults.

Valves become thicker and more rigid.

Aorta may dilate.

Myocardial muscle becomes less efficient.

Diastolic filling and systolic filling are slower; overall reduced pump efficiency.

Recognize the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in women.

No specific information provided in the notes on increased risk for women.

Explain lifestyle practices that promote cardiovascular health in later life.

Diet: Low fat, high fiber; fruits/vegetables; complex carbohydrates; omega-{3} fatty acids (fish 2x/week); reduce red meat and highly processed foods; limit alcohol. Emphasize DASH diet (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low sodium). Prefer olive oil (omega-{6}), avoid trans fats; ensure adequate hydration and fiber.

Exercise: 30 minutes moderate activity most days or 20 minutes vigorous activity 3 days/week; promote stair climbing and parking farther away. Essential warm-up and cool-down for cardiac patients; avoid abrupt high-intensity starts.

Smoking cessation: Implement stress management techniques (yoga, meditation); consider acupuncture to assist quitting smoking.

Discuss the following cardiovascular conditions including cues (signs and symptoms), risk factors, management for:

Hypertension (HTN)

Thresholds: Hypertension defined as systolic > 130 mmHg or diastolic > 80 mmHg. Hypertensive crisis occurs at SBP \ge 180 mmHg or DBP \ge 120 mmHg.

Symptoms: Morning headaches (in the back of the head), nosebleeds, dizziness or confusion with extremes of BP.

Management: Blood pressure readings should be repeated at multiple times and in different positions (lying, sitting, standing); use the arm with the higher reading for subsequent measurements.

Hypotension

Causes: Anaphylactic shock, hypovolemia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, orthostatic hypotension.

Orthostatic Hypotension: A drop in blood pressure when standing, significant if \ge 20 mmHg systolic or \ge 10 mmHg diastolic drop.

Congestive heart failure (CHF)

Mentioned as a condition contributing to altered tissue perfusion. (No detailed cues or management provided in the notes).

Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Risk factors: Prolonged immobilization.

Symptoms: Sudden shortness of breath, a sense of impending doom, low-grade fever.

Management: Includes heparin, warfarin, thrombolysis with alteplase in some cases, and sometimes surgical clot retrieval. Long-term anticoagulation (e.g., clopidogrel with aspirin) is common.

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Description: Same as ischemic heart disease; risk increases with aging.

Cues: Angina is chest pain due to myocardial oxygen supply-demand mismatch.

Triggers: Classic triggers include exertion and cold exposure (e.g., shoveling snow).

Angina

Description: Same as chest pain.

Atypical presentations: Possible reflux-like symptoms or digestion-related pain.

Management: Nitroglycerin use (vasodilates); up to 3 doses every 5 minutes for 15 minutes. Seek further care if relief occurs but symptoms recur or persist.

Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Management: Post-MI rehabilitation emphasizes warm-up and cool-down during exercise to prevent injury; gradual progression of activity.

Hyperlipidemia

Assessment: Involves measurement of LDL, HDL, and triglycerides; requires fasting for 12 hours before lipid testing.

Targets: HDL goal is > 60 mg/dL; triglycerides are measured after fasting.

Management: First-line pharmacotherapy is statins.

Arrhythmias

General arrhythmias are not detailed, but Atrial Fibrillation is specifically discussed.

Atrial Fibrillation (AFib)

Description: The most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia; often asymptomatic, detected via EKG or irregular pulse. Types include paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent.

Major risk: Stroke due to blood pooling and clot formation in the atria.

Management: May include rate control, cardioversion, or ablation.

Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD) / Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD)

Description: PVD includes slow progression of circulation problems, commonly affecting the lower extremities. PAD specifics include claudication, numbness, and weakness.

Cues: Claudication (pain with walking due to insufficient leg perfusion), hair loss on legs, stasis ulcers on lower extremities, medial lower leg ulcers.

Interventions: Stop smoking, exercise, monitor lower-extremity pulses, and proper foot care.

Complication: Diabetes complicates healing and increases the risk of amputation.

Arteriosclerosis

Atherosclerotic heart disease is mentioned as contributing to altered tissue perfusion. (No direct differentiation or detailed discussion of arteriosclerosis itself).

Diabetic problems

Contributes to altered tissue perfusion. Complicates healing and increases the risk of amputation in PAD.

Aneurysms

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): Pulsations in the abdomen may indicate an aneurysm; risk if dissection occurs.

Management: Early detection allows repair; otherwise, there is a high mortality risk.

Varicose Veins

Description: Dilated, tortuous veins in the legs.

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

Description: Includes Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE).

Risk factors: Increased with prolonged immobilization.

Prevention: Leg elevation, compression stockings, and early ambulation when possible.

Identify risk factors for pulmonary emboli in older adults.

Risk factor: Prolonged immobilization.

Explain how atypical presentations can delay diagnosis.

Atypical presentations of angina/chest pain (e.g., reflux-like symptoms, digestion-related pain) are possible and can delay diagnosis.

Recognize that most adults over 70 have some degree of coronary artery disease.

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) risk increases with aging. (The specific statistic "most adults over 70" is implied rather than explicitly stated).

Discuss atrial fibrillation as the most common sustained arrhythmia in older adults.

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is the most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia.

Identify the major contributing factor to ischemic stroke.

Atrial fibrillation (AFib): A major risk for stroke due to blood pooling and clot formation in the atria.

Differentiate between atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis in older adults.

Atherosclerotic heart disease is mentioned as contributing to altered tissue perfusion, but a specific differentiation between atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis is not provided.

Discuss ways to promote circulation.

Interventions for PVD: Stop smoking, exercise, and monitor lower-extremity pulses.

Prevention of VTE: Leg elevation, compression stockings, and early ambulation.

General cardiovascular health recommendations: Diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and stress management.

Discuss foot care for persons with peripheral vascular disease.

Proper foot care is a key intervention for Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD).

Describe complications of vascular changes, including varicosities, falls, ulcerations, and infections.

Complications: Varicose veins (dilated, tortuous veins), stasis ulcers on lower extremities (due to poor perfusion), medial lower leg ulcers (in PAD), and edema from venous pooling.

Diabetes complicates healing and increases the risk of amputation.

Orthostatic hypotension, a condition related to vascular changes, can increase the risk of falls.

Apply nursing interventions to promote cardiovascular health in older adults.

Prevention framework: Primary (prevent disease in healthy individuals), Secondary (support those diagnosed to avoid complications), and Tertiary (maximize function and rehabilitation to prevent disability).

Clinical assessment: Employ a head-to-toe assessment approach, looking for redness, edema, pallor, and nail bed changes. Inquire about changes in function, physical or mental status, dizziness, exercise tolerance, alcohol or drug use, and vitamins/supplements.

Blood pressure and cardiovascular checks: Performed in multiple positions and arms; using the arm with the higher reading for subsequent measurements.

Documentation practices: Emphasize the importance of asking clarifying questions during patient interviews.

Spirituality and Erikson: integrity and meaning

Erik Erikson’s theory (referenced as Ericsson in some notes): achieving integrity in late life is supported by a spiritual need for meaning and purpose

Key concept: meaning and purpose helps individuals believe in the future and stay committed to their beliefs even when facing pain or adversity

Question-and-answer example:

Question: According to Erikson, achieving integrity in late life is supported by this spiritual need.

Answer: Meaning and purpose

Point value: 100

Related concept: hope as a spiritual need helps people believe in the future and remain committed to those who suffer

Question: The spiritual need that helps people believe in the future and commit to those who suffer is what?

Answer: Hope

Point value: 300

Spiritual concepts and terms observed in the session

Spirituality: The relationship and feelings that connect humans to the divine transcending the physical world

Question: The relationship and feelings that connect humans to the divine transcending the physical world. What is spirituality?

Answer: Spirituality

Spiritual distress vs. crisis: Disruption in beliefs or practices relating to faith leaving spiritual needs unfulfilled (category: Definitions and concepts)

Visible cues of spirituality: Physical or symbolic signs (e.g., rosary or Bible present) that indicate spiritual practice or needs

Question: A patient wearing a rosary or keeping a Bible nearby is providing this type of clue.

Answer: A visible cue (of spirituality)

Spiritual assessment vs. addressing spiritual needs: Distinguishing between assessing spirituality and interventions to support spiritual practices

Core nurse goal in spiritual care: Not conversion, but helping the patient discuss spiritual issues and maintain practices

Time for prayer/reflection/meditation as a practice: Providing uninterrupted time for these activities is an aspect of honoring solitude

Most important spiritual need: Unconditional [need]; context suggests unconditional acceptance or love

Meaning and purpose as a core construct: Finding meaning and purpose is central to addressing spiritual needs

Other items mentioned: care planning should include honoring viewing preferences, open expression of grief, follow-up support groups, and consumer protection in funeral decisions (example given: advocate to avoid coercive or costly funeral expenses)

World religions and related concepts (examples from the session)

Kosher: Orthodox Jewish dietary law that prohibits mixing meat and dairy

Sabbath observance: Seventh-day Adventists observe Saturday as Sabbath

Prayer direction in Islam: Prayer must be performed facing the holy city Mecca (Mecca is the intended answer in the session, noted as Magna in the prompt)

Meditation and enlightenment: Buddhism practice includes meditation and following the Eightfold Path (eightfold path referenced as “eight path eightfold path”)

Religion as a human-constructed system: A term describing structures, rituals, and rules for relating to God or a higher power

Nursing interventions to address spiritual needs (evidence-based framing in the session)

Examples of interventions: Respect rituals, provide scripture, arrange clergy support

Evidence-based premise cited: Supporting spirituality can enhance health and healing

Nursing role emphasis: Facilitate discussions on spiritual issues and accommodate patient practices

Key educational point for practice: The nurse’s goal is not conversion but to support the patient’s spiritual needs and practices

In Islam, prayer direction; in Judaism, kosher; in Adventism, Sabbath; general care includes spiritual assessment and ongoing support

End-of-life care and care planning themes (highlights from the session)

Nonpharmacologic end-of-life pain or comfort measures: Two examples discussed (e.g., massage, acupuncture) as part of a broader list

Evidence-based nursing focus: Meeting spiritual needs can support health and healing even near end of life

Patient-centered care: Provide uninterrupted time for prayer/reflection/meditation; avoid pressuring patients; support their rituals

The nurse’s broad goals: Ensure comfort, support meaning and dignity, and respect patient and family wishes

Cardiovascular aging and disease: key concepts and clinical signs

Aging effects on the cardiovascular system:

Valves become thicker and more rigid

Aorta may dilate

Myocardial muscle becomes less efficient

Diastolic filling and systolic filling slower; overall reduced pump efficiency

Conditions contributing to altered tissue perfusion:

Atherosclerotic heart disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF)

Varicose veins, diabetes, cancer, renal failure

Blood dyscrasias: anemia, thrombosis, transfusion needs

Causes of hypotension that compromise perfusion:

Anaphylactic shock, hypovolemia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, orthostatic hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension: drop in blood pressure when standing; significant if exceeds certain thresholds

Tachycardia as a compensatory response to poor perfusion

Peripheral symptoms of poor perfusion:

Claudication (pain with walking due to insufficient leg perfusion)

Edema from venous pooling

Hair loss on legs; hair on toes/feet may indicate perfusion level

Stasis ulcers on lower extremities

Respiratory signs of poor perfusion: dyspnea, rapid respirations

Capillary refill and cool/cold extremities as perfusion checks

Restlessness as a sign of hypoxia/poor perfusion

General cardiovascular health recommendations:

Diet: low fat, high fiber; fruits/vegetables; complex carbohydrates; omega-3 fatty acids (fish 2x/week); reduce red meat and highly processed foods; limit alcohol

Exercise: 30 minutes moderate activity most days or 20 minutes vigorous activity 3 days/week; promote stair climbing and parking far away

Smoking cessation; stress management (yoga, meditation); consider acupuncture to assist quitting

Nutrition tips: prefer olive oil (omega-6), avoid trans fats; ensure adequate hydration and fiber

CRP as an inflammatory marker: elevated CRP indicates higher risk of cardiovascular issues; confounding conditions exist (e.g., RA, lupus)

Lipids and cholesterol management:

LDL, HDL, triglycerides; fasting for 12 hours before lipid testing

Target: HDL > 60; triglycerides measured after fasting

First-line pharmacotherapy: statins

Blood pressure basics:

Normal ranges and hypertension thresholds discussed; readings should be repeated at multiple times and in different positions

Positions for BP measurement: lying, sitting, standing; reading differences > 20 mmHg systolic or > 10 mmHg diastolic may indicate positional hypotension

Two-arm checks and using the arm with the higher reading for subsequent measurements

Heart sound and pulse examination:

Five heart valve areas to listen to: aortic, pulmonic, Erb’s point, tricuspid, mitral

Apical impulse location: fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line; count apical pulse for a full minute

Documentation of pulses: 0 = absent, 1 = thready, 2 = normal, 3 = strong, 4 = bounding

Pulses to assess bilaterally for symmetry; brachial pulse location: medial to the biceps region

Hypertension specifics observed in the session:

Normal BP definitions used in the session: “greater than 130 systolic and greater than 80 diastolic” signifying hypertension per the material

Stage classifications (informal ones referenced): crisis when SBP ≥ 180 or DBP ≥ 120; other stages noted via rising SBP/DBP

Common symptoms of hypertension: morning headaches in the back of the head; nosebleeds; dizziness or confusion with extremes of BP

Myocardial infarction and ischemic heart disease:

Angina and chest pain are the same concept; atypical presentations possible (reflux-like symptoms, digestion-related pain)

Nitroglycerin use: vasodilates; up to 3 doses every 5 minutes for 15 minutes; seek further care if relief occurs but symptoms recur or persist

Post-MI rehab emphasis: warm-up and cool-down during exercise to prevent injury; gradual progression of activity

Atrial fibrillation (AFib):

Most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia; often asymptomatic, detected via EKG or irregular pulse

Types: paroxysmal, persistent, permanent

Major risk: stroke due to blood pooling and clot formation in the atria; management may include rate control, cardioversion, or ablation

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) / Peripheral artery disease (PAD):

PVD includes slow progression of circulation problems; commonly affects lower extremities

PAD specifics: claudication, numbness, weakness; medial lower leg ulcers

Interventions: stop smoking, exercise, monitor lower-extremity pulses, proper foot care; diabetes complicates healing and risk of amputation

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA):

Pulsations in the abdomen may indicate aneurysm; risk if dissection occurs

Early detection allows repair; otherwise high mortality risk

Varicose veins and venous thromboembolism (VTE):

Varicose veins: dilated, tortuous veins in the legs

VTE includes DVT and PE; risk increased with prolonged immobilization; prevention includes leg elevation, compression stockings, and early ambulation when possible

Pulmonary embolism (PE) management observed in session:

Treatments include heparin, warfarin, thrombolysis with alteplase in some cases, sometimes surgical clot retrieval

Long-term anticoagulation (e.g., clopidogrel with aspirin) is common

PE symptoms can include sudden shortness of breath and a sense of impending doom; fever may be low-grade

Coronary artery disease / Ischemic heart disease:

CAD is the same as ischemic heart disease; risk with aging; angina is chest pain due to myocardial oxygen supply-demand mismatch

Classic trigger scenarios include exertion and cold exposure (e.g., shoveling snow)

Diet, lipids, and diet-related risk reduction details:

Emphasize DASH diet (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low sodium)

Focus on omega-3 fatty acids from fish; limit saturated fats and trans fats; encourage complex carbohydrates and fiber

Exercise prescription and rehabilitation emphasis for cardiac patients:

Warm-up and cool-down are essential; avoid abrupt high-intensity starts

Overall prevention framework:

Levels of prevention: Primary (prevent disease in healthy individuals), Secondary (support those diagnosed to avoid complications), Tertiary (maximize function and rehabilitation to prevent disability)

General clinical assessment tips and exam practice:

Head-to-toe assessment approach; look for redness, edema, pallor, nail bed changes

History questions: changes in function, physical or mental status, dizziness, exercise tolerance, alcohol or drug use, vitamins/supplements

Blood pressure and cardiovascular checks should be performed in multiple positions and arms

Documentation practices and the importance of asking clarifying questions during patient interviews

Formulas, numbers, and key thresholds (as referenced in the transcript)

Blood pressure thresholds (as presented in the session):

Hypertension threshold mentioned: > 130 systolic or > 80 diastolic

Hypertensive crisis threshold (mentioned in context): SBP ≥ 180 or DBP ≥ 120

Orthostatic hypotension definition used: a drop in blood pressure of ≥ 20 mmHg systolic or ≥ 10 mmHg diastolic upon standing

Apical pulse assessment:

Location: fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line

Duration: count for a full minute

Pulse grading (qualitative scale):

0: absent, 1: thready, 2: normal, 3: strong, 4: bounding

Lipids and cardiovascular markers (fasting values):

HDL goal: > 60 mg/dL

Triglycerides: measured after fasting (typically ~12 hours)

LDL targets and total cholesterol not explicitly quantified in the transcript, but statins are noted as first-line therapy for hyperlipidemia

Five valve areas for auscultation (names to memorize):

Aortic, Pulmonic, Erb’s point, Tricuspid, Mitral

ch22, 27, 28

After reading these chapters, you should be able to:

1. Describe effects of aging on nervous system.

FROM BOOK:

With age, loss of nerve cell mass causes some atrophy of the brain and spinal cord, and brain weight decreases. The number of nerve cells declines, each cell has fewer dendrites, and some demyelinization of the cells occurs. These changes slow nerve conduction. Response and reaction times are slower; reflexes become weaker.

Plaques, tangles, and atrophy occur in the brain to varying degrees; there is not always a relationship between these changes and cognitive function. Free radicals accumulate with age and may have a toxic effect on certain nerve cells. Cerebral blood flow decreases about 20% as fatty deposits gradually accumulate in the blood vessels, and decreases are even greater in persons with small-vessel cerebrovascular disease due to diabetes and hypertension; this contributes to an increased risk of strokes. The brain has a greater ability to compensate after injury than does the spinal cord, but this ability to compensate declines with age.

Intellectual performance tends to be maintained until at least age 80 in the absence of neurologic or vascular disease, although a slowing in central processing delays the time required to perform tasks. Verbal skills are well maintained until age 70, after which there is a gradual reduction in vocabulary, a tendency to make semantic errors, and abnormal prosody (rhythm and intonation). Other age-related changes in intellectual function are subtle but can be detected as difficulty learning, especially languages, and forgetfulness in noncritical areas.

The general lack of replacement of neurons affects the sensory organs’ function, which becomes less acute with age. The number and sensitivity of sensory receptors, dermatomes, and neurons decrease, resulting in dulling of tactile sensation. There is also some decline in the function of cranial nerves mediating taste and smell. Increased levels of taste, sound, scents, touch, and lighting are required for perception by older persons as compared with younger adults.

It must be remembered that these changes do not affect all individuals similarly. Genetic makeup, diet, lifestyle practices, and other factors influence the health and function of the neurologic system.

2. List risk factors for neurologic problems in older adults.

FROM PP:

FROM BOOK:

3. Describe measures to promote neurologic health, promote independence, and reduce risk of injury in older adults.

4. Identify signs and symptoms of neurologic disorders in older adults.

5. Describe symptoms, unique features and nursing care for patients with Parkinson’s disease, transient ischemic attacks, and cerebrovascular accidents in older adults.

FROM PP:

FROM BOOK:

6. List measures that promote mental health for older adults.

7. Describe symptoms and care for an older adult with depression.

FROM PP:

FROM BOOK:

8. Identify indications of suicidal thoughts in older adults.

FROM PP:

FROM BOOK:

9. Describe interventions to reduce anxiety in older adults.

FROM PP:

10. Discuss signs of substance abuse in older adults. Identify nursing actions to manage disruptive behavior associated with mental health conditions in older adults.

FROM PP:

11. Differentiate delirium from dementia.

FROM PP:

12. Identify factors that cause delirium.

FROM PP:

13. Describe characteristics, symptoms, and management of dementia.

FROM PP:

14. List causes of dementia.

15. Outline nursing considerations for older adults with dementia.

Normal aging: neurological function in older adults

Normal aging changes (not pathological): progression over time in the nervous system

Neuron loss: begins after about age 25; more nerve cells lost as age increases

Neurotransmitters: fewer neurotransmitters available in aging brain

Nerve conduction and reaction time: slower in older adults

Brain atrophy: brain size and neurons decrease with age; space increases on imaging

Plaques: plaques form in nerve cell bodies during aging

Cerebral blood flow: slows somewhat with age

Hippocampus changes: memory retrieval and storage rely on the hippocampus; aging leads to changes there

Activating system changes: sleep-cycle regulation alterations

Sensory decline: receptors decrease in number and sensitivity; cranial nerves show aging-related changes

Vision, hearing, taste, smell, vibratory sensation: often diminished

Temperature sensation: less able to sense temperature changes; environment safety considerations

Balance and postural control: increased risk for postural hypertension and falls; sensitivity to medications that lower blood pressure on standing up

Intellectual maintenance: intellect generally preserved; many argue wisdom and emotional intelligence may improve or stay strong into later years; verbal skills often preserved until around age 70, then vocabulary can decline

Overall nursing task: distinguish normal aging from pathological changes; monitor for differences in presentation and degree

Clinical manifestations linked to normal aging (summary):

Sleep changes: less REM sleep; longer time in stages 1–2; easier to wake; daytime sleepiness may increase

Learning: altered ability to learn new information quickly, though learning is still possible with effort

Memory: storage/retrieval affected via hippocampus; occasional difficulty recalling names or words is common and usually gradual

Vision/hearing changes: sensory deficits impact communication and safety

Taste/smell changes: can influence nutrition; adapt to maintain intake

Postural hypertension and balance issues: greater risk with antihypertensive or diuretic therapies; careful drug management needed

Temperature regulation: environmental safety importance

Cognitive function and intellect: intelligence maintained; some decline in processing speed, but not necessarily loss of intellect

Functional status: slower task performance; need for supports or assistive devices as needed

Red flags requiring further evaluation (nursing alarm signs):

New headaches, new vision changes

Sudden deafness or tinnitus

Rapid mood or personality changes

Altered consciousness or cognition

New clumsiness or unstable gait

Numbness or tingling in extremities or unusual nerve sensations

Parkinson's disease (PD)

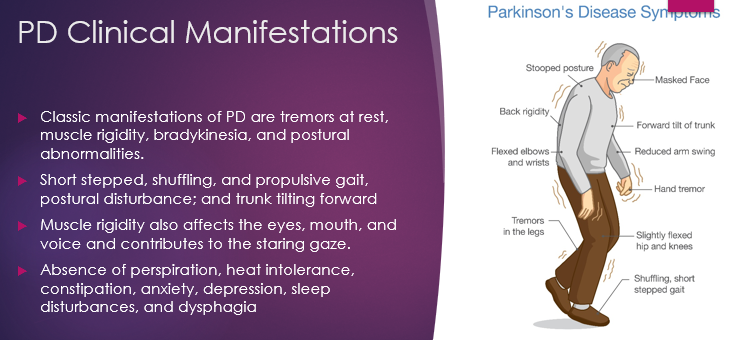

Pathophysiology: decreased dopamine in basal ganglia; balance between acetylcholine and dopamine disrupted

Neurotransmitter role: acetylcholine is excitatory; dopamine enables smooth, controlled movement

Classic motor symptoms: resting tremor (often initial), bradykinesia (slowness of initiation), impaired postural reflexes

Typical body presentation: stooped/forward-leaning posture, rigid back, shuffling gait, masked facial expression

Common risk factors: genetic (autosomal dominant defect on chromosome 4) and environmental factors; potential drug/toxin exposure; trauma history

Non-motor features: heat intolerance, constipation, depression; decreased perspiration; dysphagia risk with disease progression

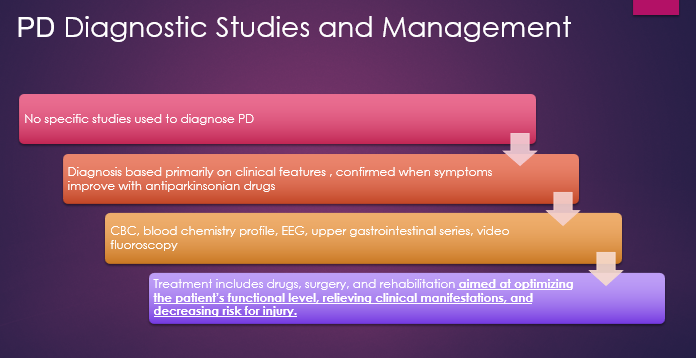

Diagnosis: clinical presentation; no definitive lab test; responds to dopaminergic therapy

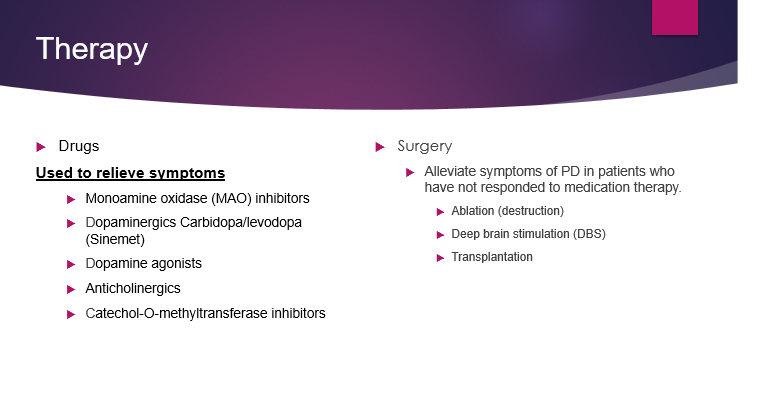

Treatments (not curative; symptom management):

Dopaminergic therapy: carbidopa-levodopa (Sinemet) — levodopa precursor to dopamine; carbidopa inhibits peripheral breakdown

Dopamine agonists and anticholinergics to mitigate symptoms and side effects

Catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors to prolong dopamine effect

Surgical options (for selected patients):

Ablation and deep brain stimulation (DBS) reduce aberrant neural activity

Transplantation and stem cell approaches under investigation

Nursing goals and interventions: maintain cognition and function, prevent injuries from impaired movement, minimize falls, safety-focused teaching

Nursing care plan elements:

Active range of motion exercises twice daily

Ambulation with assistive devices (walker/c cane) and PT consult when mobility declines

OT consult for activities of daily living and adaptive devices

Speech/swallow therapy for dysphagia and communication challenges

Nutritional assessment and support; monitor weight and dietary needs

Psychological support; address caregiver burden; community resources

Safety and management emphasis: prevent falls, plan for evolving needs, enable independent function where possible

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke

Types: hemorrhagic stroke (bleed due to vessel rupture or malformation) vs ischemic/thrombotic stroke (clot obstructs blood flow)

Onset pattern: hemorrhagic strokes often have abrupt onset; ischemic strokes may have sudden onset or evolve over minutes to hours

Common presenting symptoms: sudden unilateral facial, arm, or leg numbness or weakness (usually on one side); confusion or trouble speaking; trouble seeing in one or both eyes (hemianopsia); trouble walking, dizziness, loss of coordination; severe headache may occur

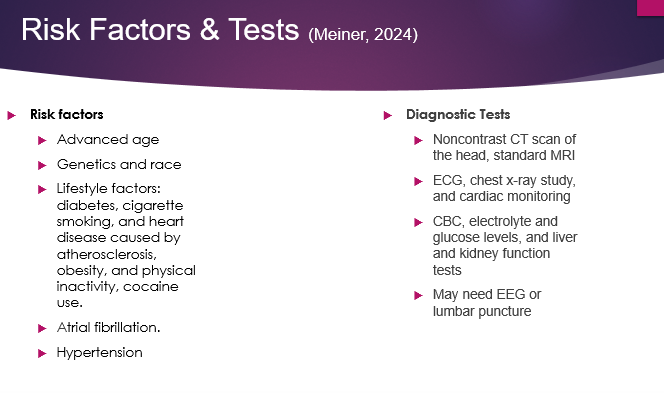

Risk factors: advanced age; genetics; African American ethnicity; diabetes; cigarette smoking; heart disease; obesity; physical inactivity; cocaine use; atrial fibrillation (AFib); hypertension (most important modifiable risk factor)

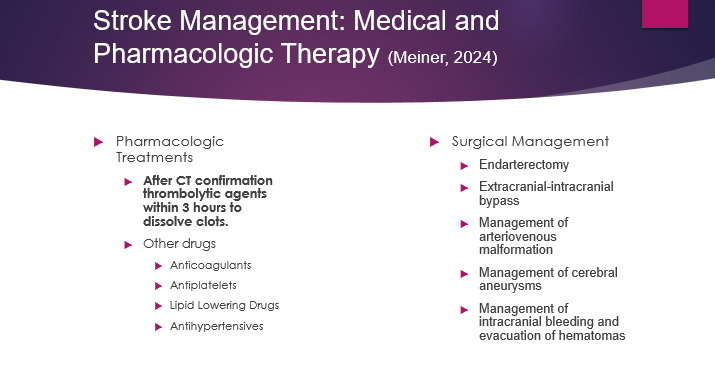

Acute management in hospital: emergency CT scan; continuous monitoring (cardiac and other vitals); labs; possibly EEG; airway protection; head of bed elevated to reduce intracranial pressure (ICP)

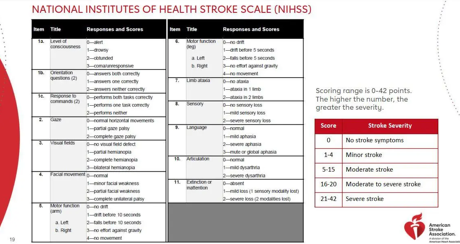

Neuro assessment and scales: NIH Stroke Scale or similar tools; assess level of consciousness, orientation, commands, gaze, visual fields, motor function, sensory, language, and cognition

Reperfusion therapy: thrombolytic therapy within a 3-hour window (time is brain); earlier treatment yields better outcomes; later guidelines may vary by stroke type and facility

Medications and interventions:

Anticoagulants or antiplatelets depending on etiology (AFib, clotting risk, etc.)

Lipid-lowering agents and antihypertensives for long-term secondary prevention

Indirect vascular procedures (carotid endarterectomy or extracranial bypass) and brain surgery for certain conditions (aneurysms, malformations, intracranial bleeding)

Acute nursing interventions: keep head elevated, monitor vitals, turn and ROM every 2 hours, encourage use of unaffected arm for ADLs, ensure swallow safety and resumption of oral intake after swallow study

Speech and language concerns: aphasia types (receptive vs expressive); visual field deficits (hemianopia); adapt patient/family education to language abilities

Outcomes and family/community planning: stroke prevention education, access to resources, and long-term rehabilitation planning

Priority considerations: safety and prevention of secondary injury; test-tasks often emphasize safety as the highest priority in acute care

Mental health and substance use in older adults

Depression in older adults: prevalent; 20–25% of adults aged 55+ have a mental health disorder (depression is especially common)

Causes and contributing factors: chronic illnesses, aging-related losses (bereavement, relocation, retirement), changes in social roles and income, societal undervaluation of older adults; medications may contribute to depression

Screening and assessment: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15); 15 yes/no questions; scores >5 suggest depression requiring further evaluation

Key signs: fatigue, constipation, psychomotor retardation, persistent depressed mood, anhedonia, low energy, social withdrawal, neglect of hygiene or self-care, somatic complaints; altered cognition common in depression and can mimic dementia

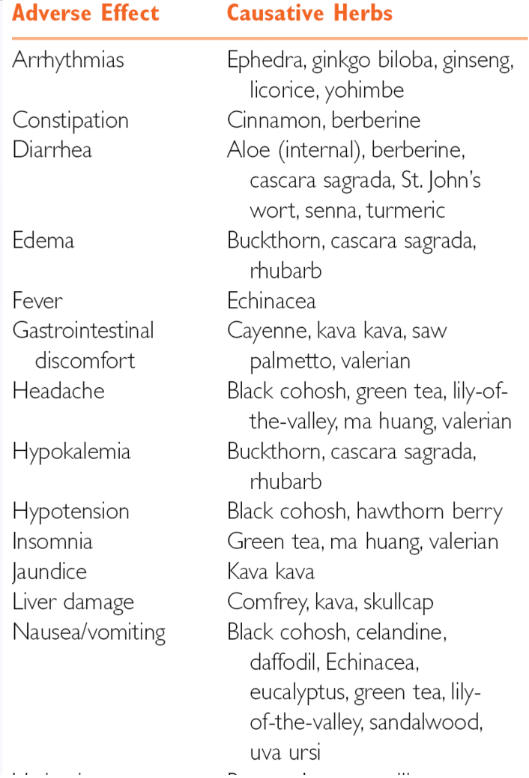

Treatment considerations: prefer SSRIs over tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) due to anticholinergic side effects and safety concerns in older adults; avoid combining SSRIs with St. John’s wort; consider psychotherapy and nonpharmacologic approaches (acupuncture, guided imagery, light therapy, sleep, exercise, nutrition)

Start low, go slow: gradual dosing and small increases to minimize side effects and falls risk; expect SSRIs to take ~2 weeks or more to show effect

Suicide risk: high among older adults; ~29% of suicide deaths occur in older adults; highest risk in men aged 85+ and older white men; risk factors include bereavement, chronic illness, social isolation, and retirement

Suicide risk assessment and response: use structured tools (e.g., National Institute of Mental Health resources) to assess frequency of thoughts, plan, past attempts, symptoms, social support; determine disposition (emergency psychiatric evaluation, inpatient care, or nonurgent follow-up); safety planning and no-suicide contracts when appropriate

Alcohol use in older adults: SMAST-G screening; two or more positive responses suggests an alcohol problem; recommended limits typically not more than one standard drink per day for older adults; withdrawal management and potential interactions with medications required; benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal can be dangerous in older adults

Anxiety in caregivers and patients: coaching and coping strategies; relaxation and deep breathing; modify perceptions of stress; psychotherapy and nonpharmacological approaches preferred; meds should be a last resort in older adults due to safety concerns

Substance abuse in older adults: not rare; may involve prescription opioids and other substances; increased risk of falls, cognitive impairment, self-neglect; discuss strategies for safe medication use and monitoring; do not overlook prescription misuse and social factors that sustain abuse

Delirium vs dementia (two “d’s”) and nursing care

Delirium: acute, abrupt global cognitive impairment with fluctuating mental status; may be worse at night; disorganized thinking; inattention; altered alertness; can include agitation or hypoactivity; hallucinations common in hospital settings

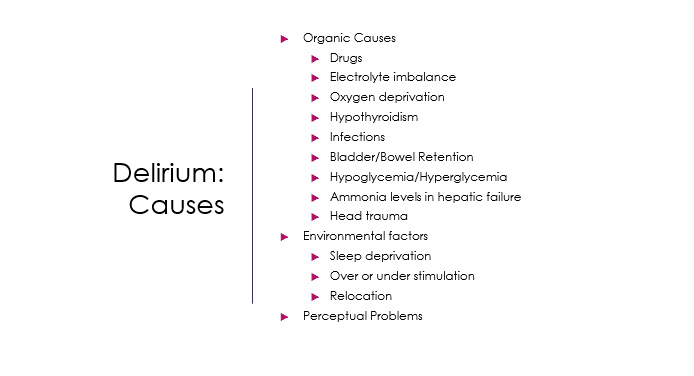

Causes of delirium: drugs, electrolyte and acid-base imbalances, oxygen delivery/deficiency (hypoxia), hypothyroidism, infections, bladder/bowel retention, hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia, sleep deprivation, sensory deprivation or overstimulation, environmental factors, ICU-related factors

Assessment and criteria: Hartford Institute criteria (common nursing tool) look for: acute change in mental status; agitation or lethargy; fluctuating or altered level of consciousness; memory impairment or disorganized thinking; inattentiveness; change in behavior; criteria usually require multiple signs; delirium is a medical emergency and must be addressed promptly