Body Fluids and Circulation

Blood:

- Blood is a special connective tissue consisting of a fluid matrix, plasma, and formed elements.

Plasma:

- Plasma is a straw-colored, viscous fluid constituting nearly 55 percent of the blood. 90-92 percent of plasma is water and proteins contribute 6-8 percent of it.

- Fibrinogen, globulins, and albumins are the major proteins.

- Fibrinogens are needed for ==clotting or coagulation of blood.==

- Globulins primarily are involved in the ==defense mechanisms of the body and the albumins help in osmotic balance.==

- Plasma also contains small amounts of minerals like ==Na+, Ca++, Mg++, HCO3 –, Cl–, etc.==

- Glucose, amino acids, lipids, etc., are also present in the plasma as they are always in transit in the body.

- Factors for ==coagulation or clotting of blood== are also present in the plasma in an inactive form.

- Plasma without clotting factors is called ==serum==.

Formed Elements:

- Erythrocytes, leucocytes, and platelets are collectively called formed elements and they constitute nearly 45 percent of the blood.

- Erythrocytes or red blood cells (RBC) are the most abundant of all the cells in the blood.

- A healthy adult man has, on average, 5 million to 5.5 million RBCs mm–3 of blood.

- RBCs are formed in the ==red bone marrow== in adults.

- RBCs are ==devoid of nuclei== in most mammals and are biconcave in shape.

- They have a red-colored, iron-containing ==complex protein called hemoglobin,== hence the color and name of these cells.

- A healthy individual has 12-16 gms of hemoglobin in every 100 ml of blood.

- These molecules play a significant role in the transport of respiratory gases.

- RBCs have an average ==life span of 120 days== after which they are destroyed in the ==spleen== (the graveyard of RBCs).

- Leucocytes are also known as white blood cells (WBC) as they are ==colorless== due to the ==lack of hemoglobin.==

- They are nucleated and are relatively lesser in number which averages 6000-8000 mm–3 of blood.

- Leucocytes are generally ==short-lived==.

- We have two main categories of WBCs – granulocytes and agranulocytes.

- ==Neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils are different types of granulocytes, while lymphocytes and monocytes are agranulocytes.==

- Neutrophils are the ==most abundant cells== (60-65 percent) of the total WBCs and basophils are the least (0.5-1 percent) among them.

- Neutrophils and monocytes (6-8 percent) are phagocytic cells that ==destroy foreign organisms== entering the body.

- Basophils secrete histamine, serotonin, heparin, etc., and are involved in ==inflammatory reactions.==

- Eosinophils (2-3 percent) ==resist infections== and are also associated with ==allergic reactions.==

- Lymphocytes (20-25 percent) are of two major types – ‘B’ and ‘T’ forms.

- Both B and T lymphocytes are responsible for the ==immune responses of the body.==

- Platelets also called thrombocytes, are ==cell fragments produced from megakaryocytes== (special cells in the bone marrow).

- Blood normally contains 1,500,00-3,500,00 platelets mm–3.

- Platelets can release a variety of substances most of which are involved in the ==coagulation or clotting of blood==.

- A reduction in their number can lead to ==clotting disorders== which will lead to excessive loss of blood from the body.

Blood Groups:

Blood Groups:

- Various types of the grouping of blood have been done.

- Two such groupings – the ABO and Rh – are widely used all over the world.

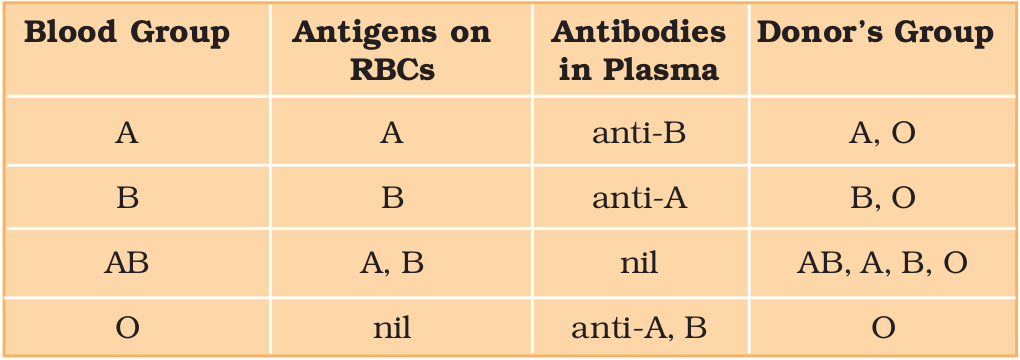

ABO Grouping:

ABO grouping is based on the ==presence or absence of two surface antigens== (chemicals that can induce an immune response) on the RBCs namely A and B.

Similarly, the plasma of different individuals contains two natural antibodies ==(proteins produced in response to antigens).==

- The distribution of antigens and antibodies in the four groups of blood, A, B, AB, and O are given below.

- During a blood transfusion, blood cannot be used; the blood of a donor has to be carefully matched with the blood of a recipient before any blood transfusion to avoid severe problems of clumping (destruction of RBC).

- ==Group ‘O’ blood can be donated to persons with any other blood group and hence ‘O’ group individuals are called ‘universal donors.==

- Persons in the ‘AB’ group can accept blood from persons with AB as well as the other groups of blood.

- Therefore, such persons are called ‘universal recipients.

Rh Grouping:

- Another antigen, the Rh antigen similar to one present in Rhesus monkeys (hence Rh), is also observed on the surface of RBCs of the majority (nearly 80 percent) of humans.

- Such individuals are called Rh positive (Rh+ve) and those in whom this antigen is absent are called Rh negative (Rh-ve).

- An Rh-ve person, if exposed to Rh+ve blood, will form specific antibodies against the Rh antigens.

- Therefore, the Rh group should also be matched before transfusions.

- A special case of ==Rh incompatibility== (mismatching) has been observed between the Rh-ve blood of a pregnant mother and with Rh+ve blood of the fetus.

- Rh antigens of the fetus do not get exposed to the Rh-ve blood of the mother in the first pregnancy as the two types of blood are well separated by the placenta.

- However, during the delivery of the first child, there is a possibility of ==exposure of the maternal blood to small amounts of the Rh+ve blood from the fetus.==

- In such cases, the mother starts preparing ==antibodies against Rh== antigen in her blood.

- In case of her subsequent pregnancies, the Rh antibodies from the mother (Rh-ve) can leak into the blood of the fetus (Rh+ve) and destroy the foetal RBCs.

- This could be fatal to the fetus or could cause ==severe anemia and jaundice in the baby.==

- This condition is called ==erythroblastosis foetalis.==

- This can be avoided by administering ==anti-Rh antibodies== to the mother immediately after the delivery of the first child.

Coagulation of Blood:

- Blood exhibits ==coagulation or clotting in response to an injury or trauma.==

- This is a mechanism to prevent ==excessive loss of blood== from the body.

- It is a clot or coagulum formed mainly of a network of threads called ==fibrins in which dead and damaged formed elements== of blood are trapped.

- Fibrins are formed by the ==conversion of inactive fibrinogens in the plasma by the enzyme thrombin.==

- Thrombins, in turn, is formed from another inactive substance present in the plasma called ==prothrombin.==

- An enzyme complex, ==thrombokinase,== is required.

- This complex is formed by a series of linked enzymic reactions (==cascade process==) involving a number of factors present in the plasma in an inactive state.

- An injury or a trauma stimulates the platelets in the blood to release certain factors which activate the mechanism of coagulation.

- Certain factors released by the tissues at the site of injury also can initiate coagulation.

- ==Calcium ions play a very important role in clotting.==

Lymph (Tissue Fluid)

- As the blood passes through the capillaries in tissues, some water along with many small water-soluble substances move out into the spaces between the cells of tissues leaving the larger proteins and most of the formed elements in the blood vessels.

- This fluid released out is called the ==interstitial fluid or tissue fluid.==

- It has the same mineral distribution as that in plasma.

- The exchange of nutrients, gases, etc., between the blood and the cells, always occurs through this fluid.

- ==An elaborate network of vessels called the lymphatic system== collects this fluid and drains it back to the major veins.

- The fluid present in the lymphatic system is called ==lymph.==

- Lymph is a colorless fluid containing ==specialized lymphocytes which are responsible for the immune responses== of the body.

- The lymph is also an important carrier of nutrients, hormones, etc.

- ==Fats are absorbed through lymph in the lacteals present in the intestinal villi.==

Circulatory Pathways:

- The circulatory patterns are of two types – open or closed.

- The open circulatory system is present in ==arthropods and molluscs== in which blood pumped by the heart passes through large vessels into open spaces or body cavities called sinuses.

- ==Annelids and chordates have a closed circulatory system== in which the blood pumped by the heart is always circulated through a closed network of blood vessels.

- This pattern is considered to be more advantageous as the flow of fluid can be more precisely regulated.

- All vertebrates possess a muscular chambered heart.

- Fishes have a ==2-chambered heart with an atrium and a ventricle.==

- In fishes, the heart pumps out deoxygenated blood which is oxygenated by the gills and supplied to the body parts from where deoxygenated blood is returned to the heart (==single circulation==).

- ==Amphibians and reptiles (except crocodiles) have a 3-chambered heart== with two atria and a single ventricle.

- In amphibians and reptiles, the left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the gills/lungs/skin and the right atrium gets the deoxygenated blood from other body parts.

- However, they get mixed up in the single ventricle which pumps out mixed blood (==incomplete double circulation==).

- ==Crocodiles, birds, and mammals possess a 4-chambered heart== with two atria and two ventricles.

- In birds and mammals, oxygenated and deoxygenated blood received by the left and right atria respectively passes on to the ventricles of the same sides.

- The ventricles pump it out without any mixing up, i.e., two separate circulatory pathways are present in these organisms, hence, these animals have double circulation.

Human Circulatory System:

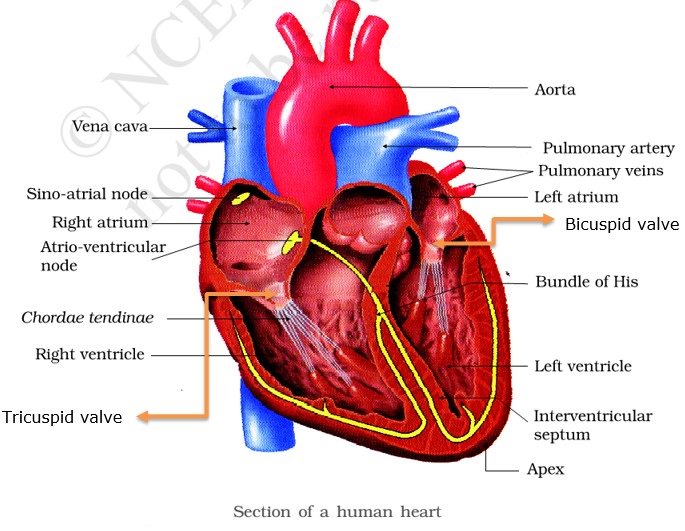

The human circulatory system, also called the blood vascular system consists of a muscular chambered heart, a network of closed branching blood vessels, and blood, the fluid which is circulated.

- The ==heart, the meso dermally derived organ, is situated in the thoracic cavity, in between the two lungs==, slightly tilted to the left.

- It has the size of a clenched fist.

- It is protected by a double-walled membranous bag, ==pericardium, enclosing the pericardial fluid.==

- Our heart has four chambers, two relatively small upper chambers called atria and two larger lower chambers called ventricles.

- A thin, muscular wall called the ==interatrial septum== separates the right and the left atria, whereas ==a thick-walled, interventricular septum==, separates the left and the right ventricles.

- The atrium and the ventricle of the same side are also separated by a thick fibrous tissue called the ==atrioventricular septum.==

- However, each of these septa is provided with an opening through which the two chambers of the same side are connected.

The opening between the right atrium and the right ventricle is guarded by a valve formed of three muscular flaps or cusps, ==the tricuspid valve, whereas a bicuspid or mitral valve guards== the opening between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

- The openings of the right and the left ventricles into the ==pulmonary artery and the aorta respectively are provided with the semilunar valves.==

- The valves in the heart allow the flow of blood only in one direction, i.e., from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles to the pulmonary artery or aorta.

- These valves prevent any backward flow.

The entire heart is made of ==cardiac muscles==.

- The walls of the ventricles are much thicker than that of the atria.

- A specialized ==cardiac musculature called the nodal tissue== is also distributed in the heart.

- A patch of this tissue is present in the right upper corner of the right atrium called the ==sino-atrial node (SAN).==

- Another mass of this tissue is seen in the lower left corner of the right atrium close to the atrioventricular septum called the ==atrioventricular node (AVN).==

- A bundle of ==nodal fibers, the atrioventricular bundle (AV bundle) continues from the AVN which passes through the atrioventricular septa to emerge on the top of the interventricular septum== and immediately divides into a right and left bundle.

- These branches give rise to minute fibers throughout the ventricular musculature of the respective sides and are called ==Purkinje fibers.==

- The nodal musculature has the ability to generate action potentials without any external stimuli, i.e., ==it is autoexcitable.==

- However, the number of ==action potentials that could be generated in a minute== varies at different parts of the nodal system.

The ==SAN can generate the maximum number of action potentials, i.e., 70-75 min–1==, and is responsible for initiating and maintaining the ==rhythmic contractile activity== of the heart.

- Therefore, it is called the ==pacemaker.==

Our heart normally beats 70-75 times in a minute (==average 72 beats min–1==).

The Cardiac Cycle:

- All four chambers of the heart are in a relaxed state, i.e., they are in ==joint diastole.==

- As the tricuspid and bicuspid valves are open, blood from the ==pulmonary veins and vena cava flows into the left and the right ventricle== respectively through the left and right atria.

- The ==semilunar valves are closed== at this stage.

- The SAN now generates an action potential that stimulates both the atria to undergo a simultaneous contraction – the ==atrial systole.==

- This increases the flow of blood into the ventricles by about ==30 percent.==

- The action potential is conducted to the ventricular side by the ==AVN and AV bundle from where the bundle of His== transmits it through the entire ==ventricular musculature.==

- This causes the ==ventricular muscles to contract, (ventricular systole), and the atria undergo relaxation (diastole)==, coinciding with the ventricular systole.

- Ventricular systole increases the ventricular pressure causing the ==closure of tricuspid and bicuspid valves due to attempted backflow of blood into the atria.==

- As the ventricular pressure increases further, the ==semilunar valves guarding the pulmonary artery (right side) and the aorta== (left side) are forced open, allowing the blood in the ventricles to flow through these vessels into the circulatory pathways.

- The ventricles now relax (ventricular diastole) and the ventricular pressure falls causing the ==closure of semilunar valves== which prevents the backflow of blood into the ventricles.

- As the ventricular pressure declines further, the ==tricuspid and bicuspid valves are pushed open by the pressure== in the atria exerted by the blood which was being emptied into them by the veins.

- The blood now once again moves freely to the ventricles.

- The ventricles and atria are now again in a relaxed (joint diastole) state, as earlier.

- Soon the ==SAN generates a new action potential== and the events described above are repeated in that sequence and the process continues.

- This sequential event in the heart which is cyclically repeated is called the ==cardiac cycle== and it consists of ==systole and diastole== of both the atria and ventricles.

- As mentioned earlier, the ==heart beats 72 times per minute, i.e., many cardiac cycles are performed per minute.==

- From this, it could be deduced that the duration of a cardiac cycle is ==0.8 seconds.==

- During a cardiac cycle, each ventricle pumps out approximately ==70 mL of blood== which is called the ==stroke volume.==

- The stroke volume multiplied by the heart rate (no. of beats per min.) gives ==the cardiac output.==

- Therefore, the cardiac output can be defined as the volume of blood pumped out by each ventricle per minute and ==averages 5000 mL or 5 liters in a healthy individual.==

- The body has the ability to alter ==the stroke volume== as well as the ==heart rate== and thereby the cardiac output.

- For example, the cardiac output of an athlete will be much higher than that of an ordinary man.

- During each cardiac cycle, two prominent sounds are produced which can be easily heard through a stethoscope.

- The ==first heart sound (lub) is associated with the closure of the tricuspid and bicuspid valves== whereas the ==second heart sound (dub) is associated with the closure of the semilunar valves.==

- These sounds are of clinical diagnostic significance.

Electrocardiograph:

- We have all seen a patient being hooked up to a monitoring machine that shows voltage traces on a screen and makes the sound “… pip… pip… pip….. peeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee” as the patient goes into cardiac arrest.

- ==This type of machine (electro-cardiograph) is used to obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG).==

- ECG is a graphical representation of the electrical activity of the heart during a cardiac cycle.

- To obtain a standard ECG a patient is connected to the machine with three electrical leads (one to each wrist and to the left ankle) that continuously monitor the heart activity.

- For a detailed evaluation of the heart’s function, multiple leads are attached to the chest region.

- Here, we will talk only about a standard ECG.

- Each peak in the ECG is identified with a letter from P to T that corresponds to a specific ==electrical activity of the heart==.

- The ==P-wave represents the electrical excitation (or depolarisation)== of the atria, which leads to the ==contraction of both the atria.==

- The QRS complex represents the ==depolarisation of the ventricles==, which initiates ==ventricular contraction.==

- The contraction starts shortly after Q and marks the ==beginning of the systole.==

- The T-wave represents the return of the ventricles from an excited to a normal state (repolarisation).

- The end of the T-wave marks the ==end of systole.==

- Obviously, by ==counting the number of QRS complexes== that occur in a given time period, one can determine the ==heartbeat rate of an individual.==

- Since the ECGs obtained from different individuals have roughly the same shape for a given lead configuration, any deviation from this shape indicates a possible abnormality or disease.

- Hence, it is of great clinical significance.

Double Circulation:

The blood flows strictly by a fixed route through Blood Vessels—the arteries and veins.

- Basically, each artery and vein consists of three layers:

- an inner lining of ==squamous endothelium, the tunica intima==,

- a middle layer of smooth muscle and elastic fibers, and ==the tunica media.==

- an external layer of ==fibrous connective tissue with collagen fibers, the tunica externa.==

- The tunica media is comparatively ==thin in the veins the blood== pumped by the right ventricle enters the pulmonary artery, whereas the ==left ventricle pumps blood into the aorta.==

- The ==deoxygenated blood pumped into the pulmonary artery== is passed on to the lungs from where the ==oxygenated blood is carried by the pulmonary veins== into the left atrium.

- This pathway constitutes ==pulmonary circulation.==

- The oxygenated blood entering the aorta is carried by a network of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries to the tissues from where the deoxygenated blood is collected by a system of venules, veins, and vena cava and emptied into the right atrium.

- This is ==systemic circulation==.

- The systemic circulation provides nutrients, O2, and other essential substances to the tissues and takes CO2 and other harmful substances away for elimination.

- A unique vascular connection exists between the digestive tract and liver called the ==hepatic portal system.==

- The hepatic portal vein carries blood from the ==intestine to the liver== before it is delivered to the systemic circulation.

- A special coronary system of blood vessels is present in our body exclusively for the circulation of blood to and from the cardiac musculature.

Regulation of Cardiac Activity:

- Normal activities of the heart are regulated intrinsically, i.e., auto-regulated by specialized muscles (nodal tissue), hence the heart is called myogenic.

- A special neural center in the medulla oblongata can moderate cardiac function through the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

- Neural signals through the sympathetic nerves (part of ANS) can increase the rate of heartbeat, the strength of ventricular contraction, and thereby the cardiac output.

- On the other hand, parasympathetic neural signals (another component of ANS) decrease the rate of heartbeat, speed of conduction of action potential, and thereby the cardiac output.

- Adrenal medullary hormones can also increase cardiac output.

Disorders of Circulatory System:

High Blood Pressure:

- Hypertension is the term for blood pressure that is higher than normal (120/80).

- In this measurement 120 mm Hg (millimeters of mercury pressure) is the systolic, or pumping, pressure and 80 mm Hg is the diastolic, or resting, pressure.

- If repeated checks of blood pressure of an individual is 140/90 (140 over 90) or higher, it shows hypertension.

- High blood pressure leads to heart diseases and also affects vital organs like brain and kidney.

Coronary Artery Disease:

- Coronary Artery Disease, often referred to as atherosclerosis, affects the vessels that supply blood to the heart muscle.

- It is caused by deposits of calcium, fat, cholesterol and fibrous tissues, which makes the lumen of arteries narrower.

Angina:

- It is also called ‘angina pectoris’.

- A symptom of acute chest pain appears when not enough oxygen is reaching the heart muscle.

- Angina can occur in men and women of any age but it is more common among the middle-aged and elderly.

- It occurs due to conditions that affect the blood flow.

Heart Failure:

- Heart failure means the state of the heart when it is not pumping blood effectively enough to meet the needs of the body.

- It is sometimes called congestive heart failure because congestion of the lungs is one of the main symptoms of this disease.

- Heart failure is not the same as cardiac arrest (when the heart stops beating) or a heart attack (when the heart muscle is suddenly damaged by an inadequate blood supply).