Chapter 17: The Economics of Education

During the 1940s, many well-paying entry-level jobs were available for people with only a high school diploma or less education.

- Over the past 50 years there has been a decrease in the demand for entry-level workers in well-paying jobs that do not require substantial levels of formal education.

- At the same time, the demand for more-educated workers has increased relative to the demand for less-educated workers.

- These demand and supply changes have increased the incentives to obtain higher levels of formal education.

The costs of education include opportunity costs and direct costs. The opportunity costs of education can be most easily measured as the value of foregone earnings, since time spent in school could have instead been spent working.

- For those pursuing primary and secondary education (i.e., kindergarten through high school, or K-12 education), the opportunity costs of going to school are low since there are not many jobs for people with less than a high school education.

- For those pursuing post-secondary education (i.e., vocational school, college, or university), the opportunity costs of going to school tend to be larger since job opportunities and average earnings increase with education.

^^The direct costs of education include tuition, fees, books, supplies, and other items necessary to attend school.^^

The marginal costs of education are the incremental costs associated with obtaining an additional year of education. At low levels of education, the direct cost of additional education is very small, since public K-12 schooling is freely available.

- The opportunity cost of K-12 education is also relatively low since the job opportunities for workers with low levels of education are limited and do not tend to pay well.

- Thus, ^^the marginal costs of education at low levels of education are relatively small.^^

- As someone's educational attainment increases, his marginal cost of education also increases.

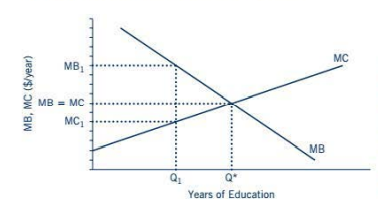

People make their educational investment decisions by weighing the marginal costs of additional education against the marginal benefits of additional education.

- If you undertake more than Q* education, your well-being will decline because you will not have high enough earnings and utility to cover the marginal costs you incur to obtain more education.

- If you undertake too little education, you would forego earnings and utility that you could obtain for less than the cost of the educational investment.

Human capital is the acquired skills and knowledge that make you more productive. The demand for workers with more human capital and higher levels of productivity tends to be higher than the demand for workers with less human capital. As a result, workers with more education and human capital tend to have more job opportunities and higher average earnings.

More-educated workers ^^tend to have higher average nonmonetary compensation than those with less education^^. Nonmonetary compensation includes things like employer-paid retirement benefits, health insurance, life insurance, and long· term disability insurance.

- Individuals with higher levels of education also report better health outcomes than those with less education.

- Those with bachelor's degrees or more education have smoking rates that are less than half of those of their high school graduate peers.

- People with more education also report higher rates of engaging in exercise than those with lower rates of education.

- Research also shows chat those with higher education are more likely to be employed in jobs where the rates of job satisfaction are high, whereas people with less education are more likely to work in jobs with lower rates of job satisfaction.

- The children of people with more education also tend to fare better than their peers.

- Children of parents with higher levels of education are more likely to participate in after-school activities like sports, scouting, arcs, or community service.

The size of the positive externality changes as the level of education changes. At low levels of education, the positive externality is likely to be large because having basic literacy and social skills has the largest impact on crime rates, job readiness, and social stability.

- <<As educational attainment expands, the positive externality from education becomes smaller because the reduction in crime and increases in social stability are greater for completing lower levels of education than for completing higher levels of education.<<

In the presence of positive externalities, too little education will be chosen relative to the socially optimal amount. Left to its own devices, a purely private market for education will result in less education than is socially optimal.

Research does not uniformly support the idea that more spending on education generates better student performance.

Various measures of student performance, including graduation rates and standardized test scores. indicate ^^very little, if any, improvements in student performance since the 1970s.^^

Researchers who have studied the effect of increased per-pupil spending on education outcomes have found inconsistent results.

Given that increased spending has not seemed to generate better educational outcomes, the educational system in the U.S. is widely criticized and calls for reform are common. Two types of school reform frequently proposed are changes in the degree of choice that parents have over where their children attend public school and changes in pay structures for teachers.

Proposals for education reform include school choice programs, raising teachers' pay, and instituting merit-based rather than seniority-based pay systems.