Study Sheet for Proving Various Types of Mathematical Statements

Quantified Statements (For all, ∀)

A quantified statement typically looks like:

"For all x∈S, property P(x) holds."

Steps to prove:

Start by assuming an arbitrary element x∈S

Show that P(x) holds for this arbitrary x

Conclude that since x was arbitrary, the statement is true for all x∈S

Example:

Prove that for all n∈Z, n² ≥ 0

Pick any n∈Z

n² ≥ 0 holds since squares are always non-negative

Conclude the proof

OR

Use counter-examples: Find an element in the domain for which the statement is false

Existential Statements (There exists, ∃)

An existential statement looks like:

"There exists x∈S such that property P(x) holds."

Steps to prove:

Find a specific example x∈S for which P(x) is true

Show that this example satisfies P(x)

Example:

Prove that there exists an even number n∈Z such that n²=4

Pick n=2

Show that 2²= 4.

Conclude the proof

Disprove: Prove the Negation

Nested Quantifiers (Both ∀ and ∃)

Nested quantifiers involve a combination of "for all" and "there exists."

Steps to prove:

Handle the outermost quantifier first.

If ∀x∃y, assume an arbitrary x and find a corresponding y

If ∃x∀y, find a specific x that works for all y

Example:

Prove that for every real number x, there exists a real number y such that y=x+1

Start with an arbitrary x∈R

Set y=x+1 and show that it works

Conclude the proof

Implications ( P ⟹ Q)

For statements of the form "if P, then Q," prove that Q follows from P

Steps to prove:

Pretend that we know statement A is true

Use the fact that statement A is true to show that statement B is true

Do not assume at any point that B is true

Example:

Prove that if n is an even integer, then n² is even.

Assume n is even, so n=2k

Show that n² = (2k)² = 4k² which is even

“Let x be a real number, and suppose that 2²^x is an odd integer. By definition, this means that 2²^x = 2n + 1 for some n ∈ Z. Now, observe that…”

If and Only If Statements ( P ⟺ Q )

For a statement "if and only if," you need to prove two directions:

P ⟹ Q and Q ⟹ P

Steps to prove:

Prove P ⟹ Q: Assume P is true, and show Q follows

Prove Q ⟹ P: Assume Q is true, and show P follows

Example:

Prove that n is even if and only if n² is even.

Prove n is even ⟹ n² is even

Prove n² is even ⟹ n is even

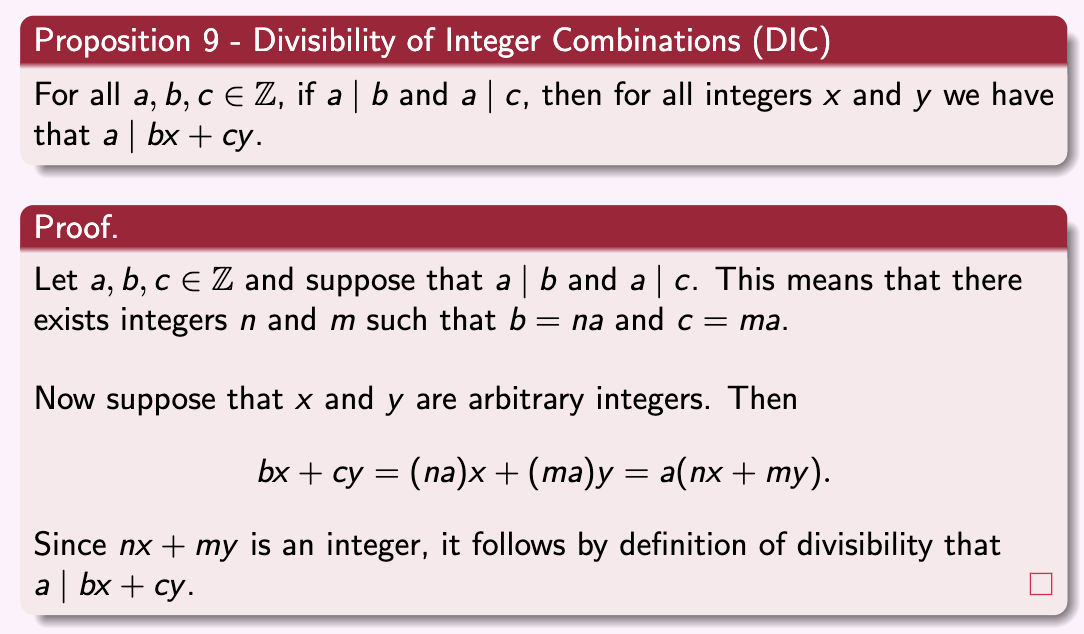

Divisibility

Transitivity of Divisibility (TD)

Divisibility by Integer Combinations (DIC)

Contrapositive ( ¬Q ⟹ ¬P)

Instead of proving P ⟹ Q directly, you can prove the contrapositive:

"If not Q, then not P."

Steps to prove:

Assume Q is false, then show that P must also be false

Example:

Prove that if n² is odd, then n is odd (contrapositive)

Contrapositive: "If n is even, then n² is even."

Prove this instead, as it's often easier

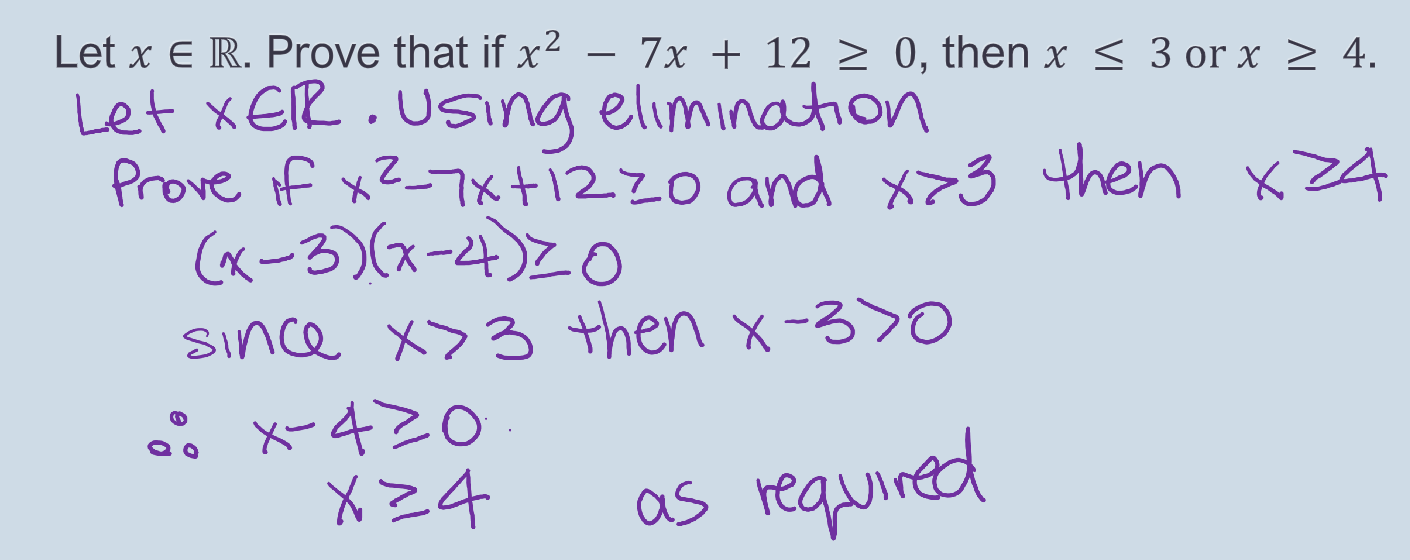

Method of Elimination

A ⟹ (B V C) = (A ∧ (¬B)) ⟹ C

Disjunction ( P ∨ Q)

For statements of the form "either P or Q," you can prove either P or Q is true

Steps to prove:

Prove one of the two parts (either P or Q)

Alternatively, consider cases and show at least one must hold

Example:

Prove that n∈Z, then n is either even or odd

Show that every integer is either divisible by 2 (even) or has a remainder of 1 (odd)

Contradiction

To prove P, assume ¬P (the opposite of P) and show that this leads to a contradiction

Steps to prove:

Assume the negation of the statement you're trying to prove

Show that this leads to a logical contradiction (something impossible)

Example:

Prove that sqrt{2} is irrational

Assume the opposite: sqrt{2} is rational

Show that this leads to a contradiction (i.e., a non-reducible fraction)

Uniqueness

To prove the existence and uniqueness of some object satisfying a property, prove:

Existence: Show that at least one such object exists.

Uniqueness: Show that if two objects satisfy the property, they must be equal.

Example:

Prove that the equation x² = 1 has a unique positive solution.

Existence: x = 1 works.

Uniqueness: The only positive solution to x² = 1 is x =1

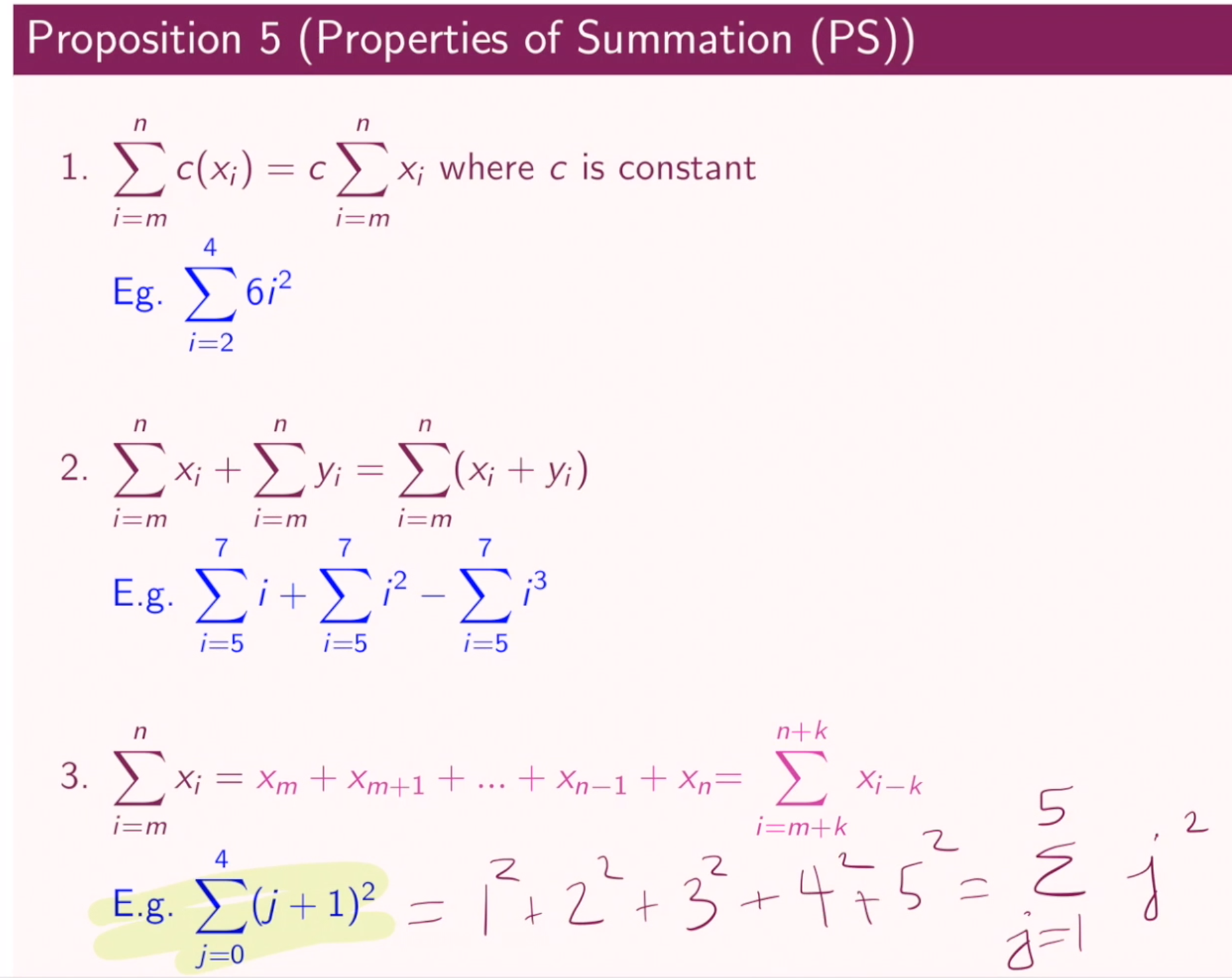

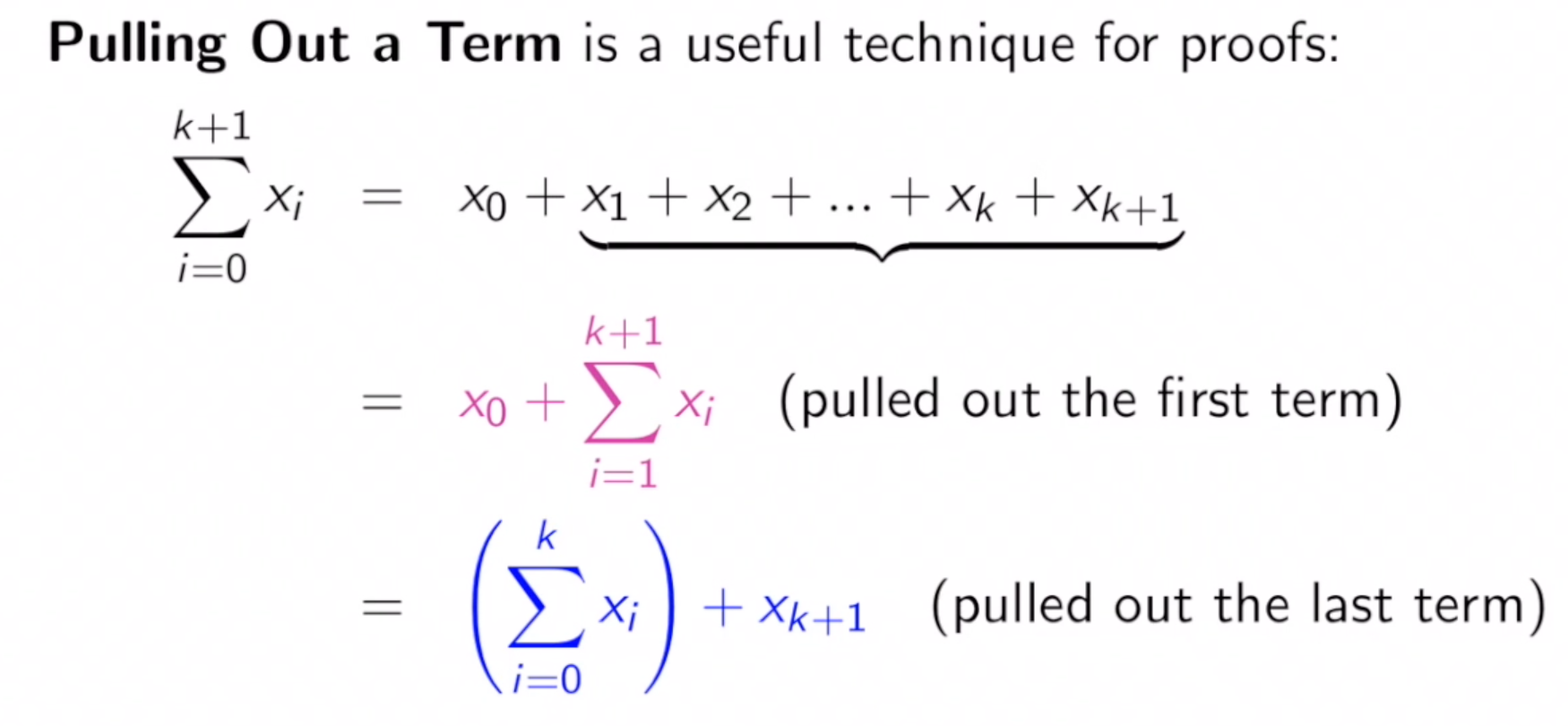

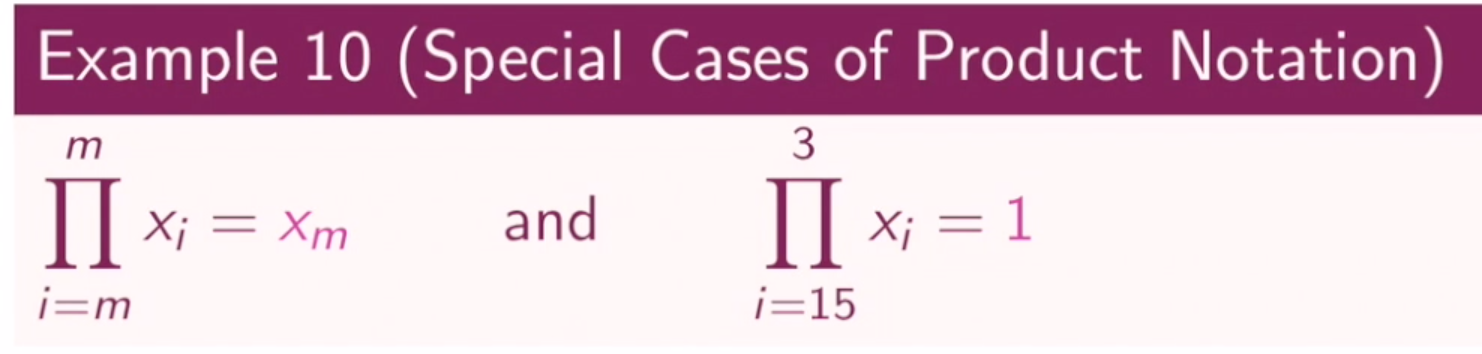

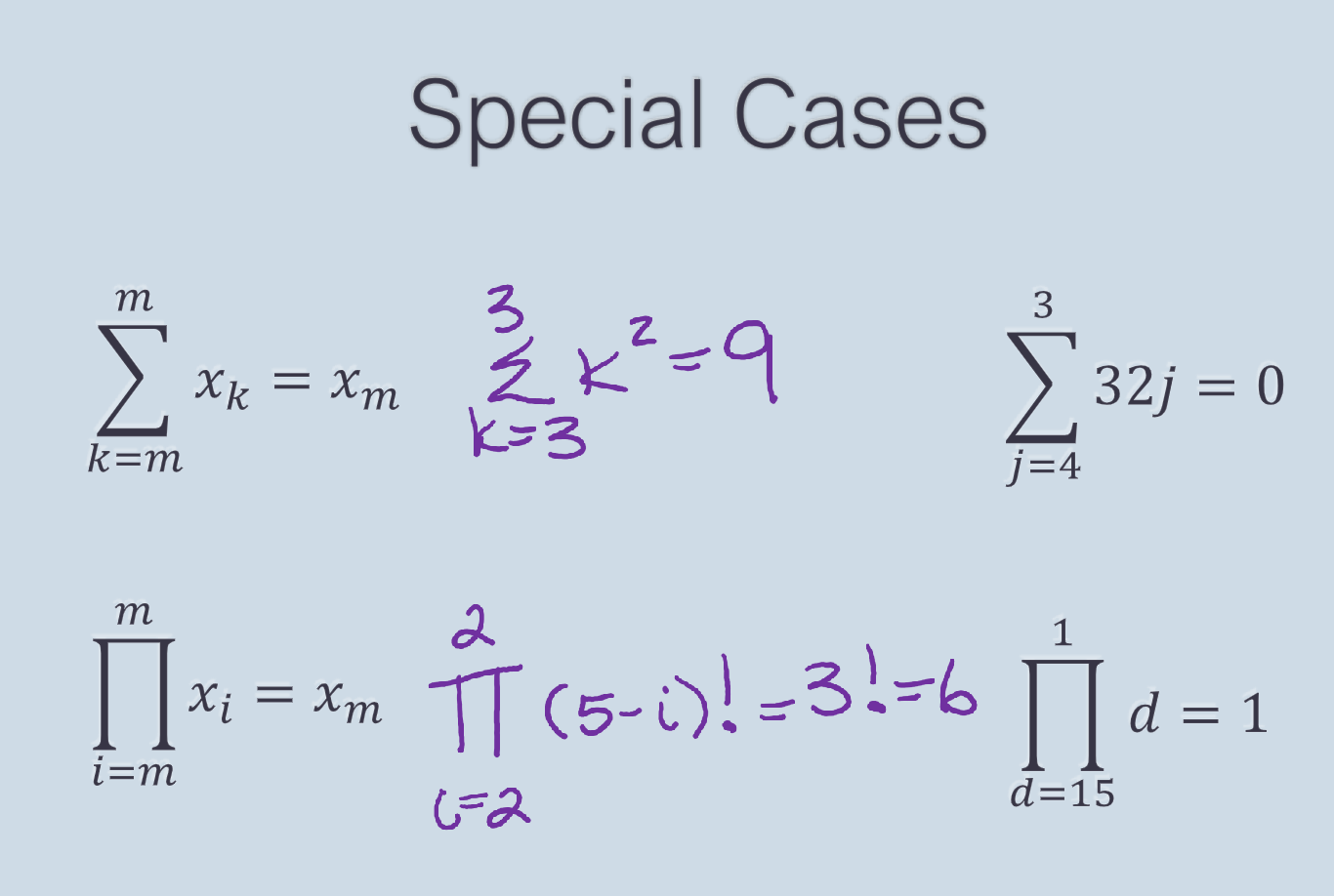

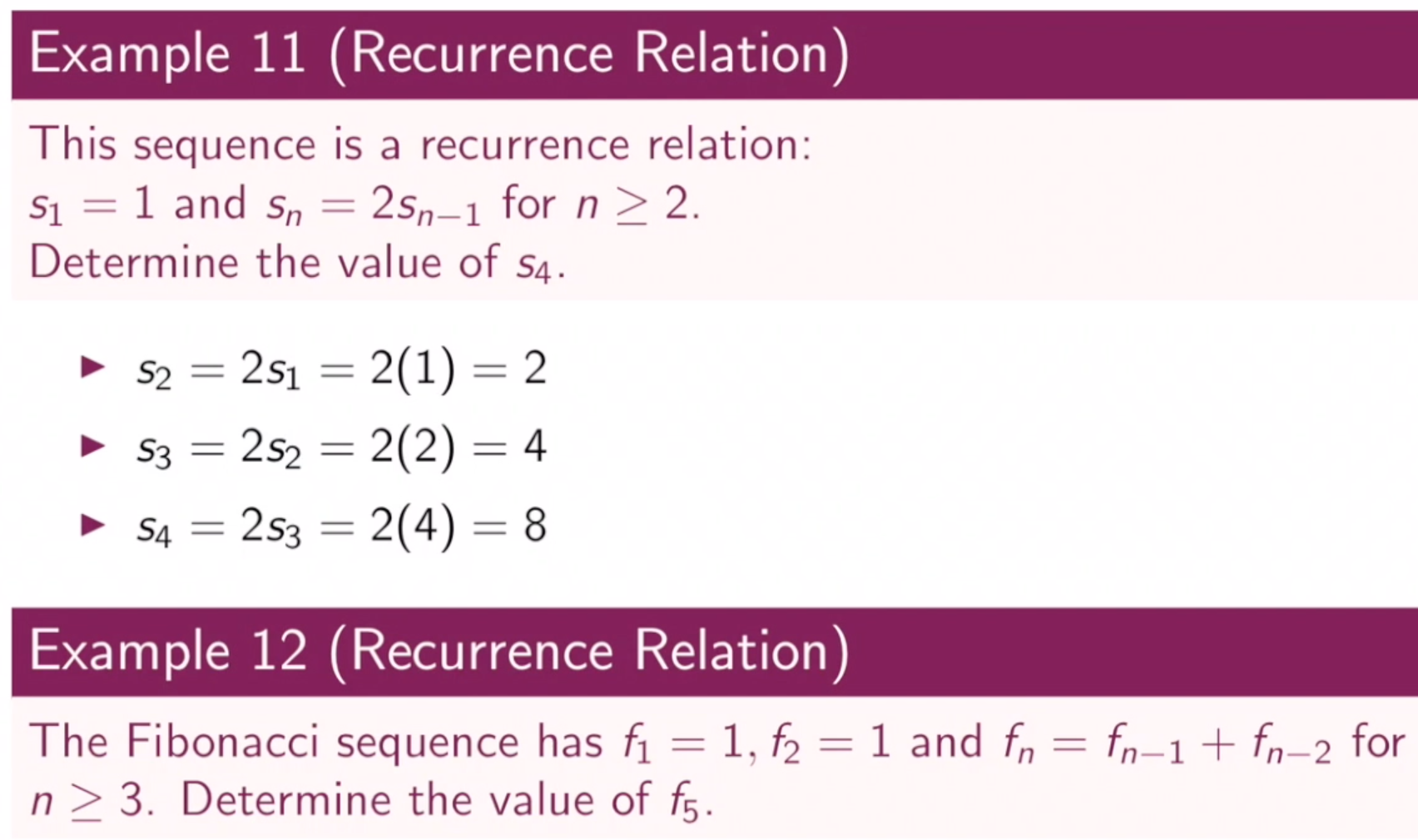

Summation

To prove results about summations or products, use mathematical induction, algebraic manipulation, or known formulas.

Steps to prove summation formulas:

Use induction or simplify using algebraic identities.

Example:

Prove that 1+2+ … + n = n(n+1)/2

Prove by induction or verify with simple algebra

Open Statements

An open statement contains variables and becomes true or false depending on the values of the variables.

Steps to prove:

Substitute specific values into the open statement to prove or disprove it

Determine conditions under which the statement is true

Example:

Is n² + 3n even or odd?

Substitute values for n to check

Subsets

Assume x∈S (start with an arbitrary element)

Prove x∈T (show it is in the larger set)

(For proper subset only): Find element in T that is not in S (this proves S≠TS)

Strong Induction

Prove that a statement holds for all natural numbers by assuming it has for all previous values (not just one previous value)

Steps to prove:

Base case: Prove the statement for the smallest number (usually n=1)

Inductive step: Assume the statement is true for all n ≤ K; and prove it holds for k+1

Example:

Prove that every number greater than 1 is divisible by a prime

Base case: 2 is prime

Inductive step: Assume the statement is true for numbers up to k, and prove it for k+1

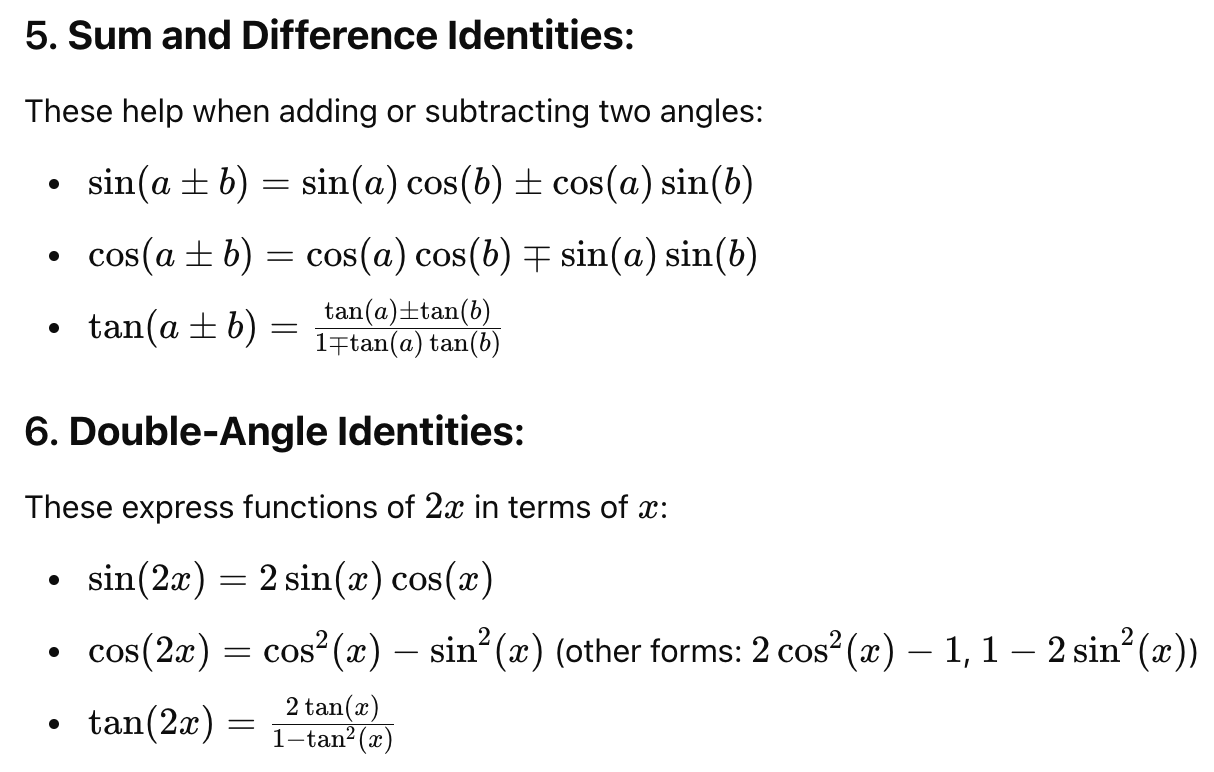

Useful Trig Identities

1. Transitivity of Divisibility (TD)

Statement: If a∣ba \mid ba∣b and b∣cb \mid cb∣c, then a∣ca \mid ca∣c.

Key Idea: Divisibility can "pass along" a chain of numbers.

Application: Use this when you know a∣ba \mid ba∣b and b∣cb \mid cb∣c, and you want to prove that a∣ca \mid ca∣c. Helpful in proofs involving multiple steps of divisibility.

2. Divisibility of Integer Combinations (DIC)

Statement: If a∣ba \mid ba∣b and a∣ca \mid ca∣c, then a∣(bx+cy)a \mid (bx + cy)a∣(bx+cy) for any integers xxx and yyy.

Key Idea: A divisor of two numbers also divides any integer combination of them.

Application: Use this in problems where you are forming linear combinations of numbers and need to prove divisibility.

3. Bounds by Divisibility (BBD)

Statement: If b∣ab \mid ab∣a and a≠0a \neq 0a=0, then ∣b∣≤∣a∣|b| \leq |a|∣b∣≤∣a∣.

Key Idea: The absolute value of a divisor must be less than or equal to the absolute value of the dividend.

Application: Use this to set bounds or restrictions on possible divisors.

4. Division Algorithm (DA)

Statement: For any integer aaa and positive integer bbb, there exist unique integers qqq (quotient) and rrr (remainder) such that a=qb+ra = qb + ra=qb+r, where 0≤r<b0 \leq r < b0≤r<b.

Key Idea: This is a core tool for understanding how division works with remainders.

Application: Crucial for solving problems involving division with remainders, including GCD calculations using the Euclidean algorithm.

5. GCD With Remainders (GCD WR)

Statement: If a=qb+ra = qb + ra=qb+r, then gcd(a,b)=gcd(b,r)\gcd(a, b) = \gcd(b, r)gcd(a,b)=gcd(b,r).

Key Idea: The gcd doesn’t change if you replace the larger number by the remainder from its division by the smaller one.

Application: This is essential in the Euclidean algorithm for finding the gcd of two numbers. Keep reducing the size of the numbers by taking remainders until you reach 0.

6. GCD Characterization Theorem (GCD CT)

Statement: For integers aaa and bbb, and a non-negative integer ddd, if ddd is a common divisor of aaa and bbb and there exist integers sss and ttt such that as+bt=das + bt = das+bt=d, then d=gcd(a,b)d = \gcd(a, b)d=gcd(a,b).

Key Idea: The gcd is the smallest positive integer that can be written as a linear combination of aaa and bbb.

Application: Use this when working with linear combinations to prove the gcd or when applying Bézout's Lemma.

7. Bézout’s Lemma (BL)

Statement: For all integers aaa and bbb, there exist integers sss and ttt such that as+bt=das + bt = das+bt=d, where d=gcd(a,b)d = \gcd(a, b)d=gcd(a,b).

Key Idea: The gcd of two numbers is a linear combination of those two numbers.

Application: Use this lemma to explicitly find the gcd by expressing it as a linear combination, often done in number theory problems.

8. Common Divisor Divides GCD (CDD GCD)

Statement: If c∣ac \mid ac∣a and c∣bc \mid bc∣b, then c∣gcd(a,b)c \mid \gcd(a, b)c∣gcd(a,b).

Key Idea: Any common divisor of two numbers must also divide their gcd.

Application: Use this to simplify problems where you need to find the gcd or prove divisibility by a common divisor.

9. Coprimeness Characterization Theorem (CCT)

Statement: gcd(a,b)=1\gcd(a, b) = 1gcd(a,b)=1 if and only if there exist integers sss and ttt such that as+bt=1as + bt = 1as+bt=1.

Key Idea: Two numbers are coprime (gcd = 1) if you can express 1 as a linear combination of them.

Application: Use this to show that two numbers are coprime or to prove related results about gcd.

10. Division by the GCD (DB GCD)

Statement: If d=gcd(a,b)d = \gcd(a, b)d=gcd(a,b), then gcd(ad,bd)=1\gcd\left(\frac{a}{d}, \frac{b}{d}\right) = 1gcd(da,db)=1.

Key Idea: If you divide two numbers by their gcd, the resulting numbers are coprime.

Application: Use this when simplifying problems by removing the gcd factor and working with smaller, coprime numbers.

11. Coprimeness and Divisibility (CAD)

Statement: If c∣abc \mid abc∣ab and gcd(a,c)=1\gcd(a, c) = 1gcd(a,c)=1, then c∣bc \mid bc∣b.

Key Idea: If aaa and ccc are coprime, and ccc divides the product ababab, then ccc must divide bbb.

Application: Useful for factoring and divisibility arguments involving coprime numbers.

Terms

WLOG: Without Lost Of Generality