AB PSYCH

MODULE 1 - WHAT IS ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY?

Understanding Abnormal Behavior

Psychology worked with the disease model for over 60 years, from about the late 1800s into the middle part of the 19th century. The focus was – curing mental disorders – and included such pioneers as Freud, Adler, Klein, Jung, and Erickson. These names are synonymous with the psychoanalytical school of thought.

In the 1930s, behaviorism, under B.F. Skinner, presented a new view of human behavior which espouses that human behavior could be modified if the correct combination of reinforcements and punishments were used.

Moving into the mid to late 1900s, a more scientific investigation of mental illness which allowed the examination of the roles of both nature and nurture and develop drug and psychological treatments to “make miserable people less miserable.” Martin Seligman later pointed out the three consequences of this scientific investigation.

1) Psychologists and psychiatrists became victimologists, pathologizers; that our view of human nature was that if you were in trouble, bricks fell on you. And we forgot that people made choices and decisions. We forgot responsibility.

2) We forgot about improving normal lives. We forgot about a mission to make relatively untroubled people happier, more fulfilled, more productive. And “genius,” “high-talent,” became a dirty word.

3) In our rush to do something about people in trouble, in our rush to do something about repairing damage, it never occurred to us to develop interventions to make people happier — positive interventions.

One attempt to address the limitations of both psychoanalysis and behaviorism came from 3rd force psychology – humanistic psychology – under such figures as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers starting in the 1960s. Humanistic psychology addressed the full range of human functioning and focused on personal fulfillment, valuing feelings over intellect, hedonism, a belief in human perfectibility, emphasis on the present, self-disclosure, self-actualization, positive regard, client centered therapy, and the hierarchy of needs.

In 1996, Martin Seligman became the president of the American Psychological Association (APA) and called for a positive psychology or one that had a more positive conception of human potential and nature. Though positive and humanistic psychology have similarities, it should be pointed out their methodology was much different. While humanistic psychology generally relied on qualitative methods, positive psychology utilizes a quantitative approach and aims to make the most out of life’s setbacks, relate well to others, find fulfillment in creativity, and finally helping people to find lasting meaning and satisfaction.

HOW DO WE DETERMINE WHAT IS ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5 for short), states that though “no definition can capture all aspects of all disorders in the range contained in the DSM-5” certain aspects are required. These include:

1) Dysfunction – includes “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning”. For example: a good employee who suddenly demonstrates poor performance may be experiencing an environmental demand leading to stress and ineffective coping mechanisms. Once the demand resolves itself the person’s performance should return to normal according to this principle.

2) Distress – When the person experiences a disabling condition “in social, occupational, or other important activities”. Distress can take the form of psychological or physical pain, or both concurrently.

Examples:

The loss of a loved one would cause even the most “normally” functioning individual pain.

An athlete who experiences a career ending injury would display distress as well.

3) Deviance – The word abnormal shows that it indicates a move away from what is normal, or the mean (i.e. what would be considered average and in this case in relation to behavior), and so is behavior that occurs infrequently. Our culture, or the totality of socially transmitted behaviors, customs, values, technology, attitudes, beliefs, art, and other products that are particular to a group, determines what is normal and so a person is said to be deviant when he or she fails to follow the stated and unstated rules of society, called social norms. What is considered “normal” by society can change over time due to shifts in accepted values and expectations.

Examples:

Homosexuality was considered taboo in the U.S. just a few decades ago but today, it is generally accepted.

PDAs, or public displays of affection, do not cause a second look by most people unlike the past when these outward expressions of love were restricted to the privacy of one’s own house or bedroom.

In the U.S., crying is generally seen as a weakness for males but if the behavior occurs in the context of a tragedy such as the Vegas mass shooting on October 1, 2017 in which 58 people were killed and about 500 were wounded while attending the Route 91 Harvest Festival, then it is appropriate and understandable.

Consider that statistically deviant behavior is not necessarily negative. Genius is an example of behavior that is not the norm.

Though not part of the DSM conceptualization of what abnormal behavior is, many clinicians add dangerousness to this list, or when behavior represents a threat to the safety of the person or others. It is important to note that having a mental disorder does not mean you are also automatically dangerous. The depressed or anxious individual is often no more a threat than someone who is not depressed and as Hiday and Burns (2010) showed, dangerousness is more the exception than the rule. Still, mental health professionals have a duty to report to law enforcement when a mentally disordered individual expresses intent to harm another person or themselves. It is important to point out that people seen as dangerous are also not automatically mentally ill.

In conclusion, though there is no one behavior that is enough to classify people as abnormal, most clinical practitioners agree that any behavior that strays from what is considered the norm or is unexpected, and has the potential to harm others or the individual, is abnormal behavior.

DEFINITION OF ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY OR PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The scientific study of abnormal behavior, with the intent to be able to reliably predict, explain, diagnose, identify the causes of, and treat maladaptive behavior is referred to as abnormal psychology. Abnormal behavior can become pathological in nature and so leads to the scientific study of psychological disorders, or psychopathology. Mental disorders are characterized by psychological dysfunction which causes physical and/or psychological distress or impaired functioning and is not an expected behavior according to societal or cultural standards.

CLASSIFYING MENTAL DISORDERS

Classification is the way in which we organize or categorize things. It provides a nomenclature, or naming system, to structure the understanding of mental disorders in a meaningful way.

Epidemiology is the scientific study of the frequency and causes of diseases and other health-related states in specific populations such as a school, neighborhood, a city, country, and the world.

Psychiatric or mental health epidemiology refers to the occurrence of mental disorders in a population. In mental health facilities, a patient presents with a specific problem, or the presenting problem, and clinicians give a clinical description of it which includes information about the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that constitute that mental disorder.

Occurrence can be investigated in several ways. First, prevalence is the percentage of people in a population that has a mental disorder or can be viewed as the number of cases per some number of people. For instance, if 20 people out of 100 have bipolar disorder, then the prevalence rate is 20%. Prevalence can be measured in several ways:

Point prevalence indicates the proportion of a population that has the characteristic at a specific point in time. In other words, it is the number of active cases.

Period prevalence indicates the proportion of a population that has the characteristic at any point during a given period of time, typically the past year.

Lifetime prevalence indicates the proportion of a population that has had the characteristic at any time during their lives.

Incidence indicates the number of new cases in a population over a specific period of time. This measure is usually lower since it does not include existing cases as prevalence does. If you wish to know the number of new cases of social phobia during the past year (going from say Aug 21, 2015 to Aug 20, 2016), you would only count cases that began during this time and ignore cases before the start date, even if people are currently afflicted with the mental disorder. Incidence is often studied by medical and public health officials so that causes can be identified and future cases prevented.

Comorbidity describes when two or more mental disorders are occurring at the same time and in the same person.

The etiology is the cause of the disorder. There may be social, biological, or psychological explanations for the disorders beginning which need to be understood to identify the appropriate treatment.

The course of the disorder is its particular pattern. A disorder may be acute meaning that it lasts a short period of time, or chronic, meaning it lasts a long period of time. It can also be classified as time-limited, meaning that recovery will occur in a short period of time regardless of whether any treatment occurs.

Prognosis is the anticipated course the mental disorder will take. A key factor in determining the course is age, with some disorders presenting differently in childhood than adulthood.

Treatment is any procedure intended to modify abnormal behavior into normal behavior. The person suffering from the mental disorder seeks the assistance of a trained professional to provide some degree of relief over a series of therapy sessions. The trained mental health professional may prescribe medication or utilize psychotherapy to bring about this change. Treatment may be sought from the primary care provider, in an outpatient fashion, or through inpatient care or hospitalization at a mental hospital or psychiatric unit of a general hospital.

PREHISTORIC AND ANCIENT BELIEFS

Prehistoric cultures often held a supernatural view of abnormal behavior and saw it as the work of evil spirits, demons, gods, or witches who took control of the person. This form of demonic possession often occurred when the person engaged in behavior contrary to the religious teachings of the time. Treatment by cave dwellers included a technique called trephination, in which a stone instrument known as a trephine was used to remove part of the skull, creating an opening. Through it, the evil spirits could escape thereby ending the person’s mental affliction and returning them to normal behavior.

Early Greek, Hebrew, Egyptian, and Chinese cultures used a treatment method called exorcism in which evil spirts were cast out through prayer, magic, flogging, starvation, having the person ingest horrible tasting drinks, or noise-making.

Greco-Roman

Thought Rejecting the idea of demonic possession, Greek physician, Hippocrates (460-377 B.C.), said that mental disorders were akin to physical disorders and had natural causes. Specifically, they arose from brain pathology, or head trauma/brain dysfunction or disease, and were also affected by heredity. Hippocrates classified mental disorders into three main categories – melancholia, mania, and phrenitis (brain fever) and gave detailed clinical descriptions of each. He also described four main fluids or humors that directed normal brain functioning and personality – blood which arose in the heart, black bile arising in the spleen, yellow bile or choler from the liver, and phlegm from the brain. Mental disorders occurred when the humors were in a state of imbalance such as an excess of yellow bile causing frenzy and too much black bile causing melancholia or depression. Hippocrates believed mental illnesses could be treated as any other disorder and focused on the underlying pathology.

Also important was Greek philosopher, Plato (429-347 B.C.), who said that the mentally ill were not responsible for their own actions and so should not be punished. It was the responsibility of the community and their families to care for them.

Greek physician, Galen (A.D. 129-199) said mental disorders had either physical or mental causes and included fear, shock, alcoholism, head injuries, adolescence, and changes in menstruation.

In Rome, physician Asclepiades (124-40 BC) and philosopher Cicero (106-43 BC) rejected Hippocrates’ idea of the four humors and instead stated that melancholy arises from grief, fear, and rage; not excess black bile. Roman physicians treated mental disorders with massage or warm baths, the hope being that their patients would be as comfortable as they could be. They practice the concept of “contrariis contrarius”, meaning opposite by opposite, and introduced contrasting stimuli to bring about balance in the physical and mental domains. An example would be consuming a cold drink while in a warm bath.

The Middle Ages – 500 AD to 1500 AD

The progress made during the time of the Greeks and Romans was quickly reversed during the Middle Ages with the increase in power of the Church and the fall of the Roman Empire. Mental illness was yet again explained as possession by the Devil and methods such as exorcism, flogging, prayer, the touching of relics, chanting, visiting holy sites, and holy water were used to rid the person of his influence. In extreme cases, the afflicted were exposed to confinement, beatings, and even execution.

Scientific and medical explanations, such as those proposed by Hippocrates, were discarded. Group hysteria, or mass madness, was also seen in which large numbers of people displayed similar symptoms and false beliefs. This included the belief that one was possessed by wolves or other animals and imitated their behavior, called lycanthropy, and a mania in which large numbers of people had an uncontrollable desire to dance and jump, called tarantism. The latter was believed to have been caused by the bite of the wolf spider, now called the tarantula, and spread quickly from Italy to Germany and other parts of Europe where it was called Saint Vitus’s dance. Perhaps the return to supernatural explanations during the Middle Ages makes sense given events of the time. The Black Death or Bubonic Plague had killed up to a third, and according to other estimates almost half, of the population. Famine, war, social oppression, and pestilence were also factors. Death was ever present which led to an epidemic of depression and fear. Near the end of the Middle Ages, mystical explanations for mental illness began to lose favor and government officials regained some of their lost power over nonreligious activities. Science and medicine were called upon to explain psychopathology.

The Renaissance – 14th to 16th centuries

The most noteworthy development in the realm of philosophy during the Renaissance was the rise of humanism, or the worldview that emphasizes human welfare and the uniqueness of the individual. This helped continue the decline of supernatural views of mental illness.

In the mid to late 1500s, Johann Weyer (1515-1588), a German physician, published his book, On the Deceits of the Demons, that rebutted the Church’s witch-hunting handbook, the Malleus Maleficarum, and argued that many accused of being witches and subsequently imprisoned, tortured, and/or burned at the stake, were mentally disturbed and not possessed by demons or the Devil himself. He believed that like the body, the mind was susceptible to illness. Not surprisingly, the book was met with vehement protest and even banned from the church. It should be noted that these types of acts occurred not only in Europe, but also in the United States.

The most famous example was the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in which more than 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft and 20 were killed. The number of asylums, or places of refuge for the mentally ill where they could receive care, began to rise during the 16th century as the government realized there were far too many people afflicted with mental illness to be left in private homes. Hospitals and monasteries were converted into asylums. Though the intent was benign in the beginning, as they began to overflow patients came to be treated more like animals than people. In 1547, the Bethlem Hospital opened in London with the sole purpose of confining those with mental disorders. Patients were chained up, placed on public display, and often heard crying out in pain. The asylum became a tourist attraction, with sightseers paying a penny to view the more violent patients, and soon was called “Bedlam” by local people; a term that today means “a state of uproar and confusion”.

Reform Movement – 18th to 19th centuries

The rise of the moral treatment movement occurred in Europe in the late 18th century and then in the United States in the early 19th century. Stressing affording the mentally ill respect, moral guidance, and humane treatment, all while considering their individual, social, and occupational needs, its earliest proponent was Francis Pinel (1745-1826). Arguing that the mentally ill were sick people, Pinel ordered that chains be removed, outside exercise be allowed, sunny and well-ventilated rooms replace dungeons, and patients be extended kindness and support.

This approach led to considerable improvement for many of the patients, so much so, that several were released. Following Pinel’s lead in England, William Tuke (1732-1822), a Quaker tea merchant, established a pleasant rural estate called the York Retreat. The Quakers believed that all people should be accepted for who they were and treated kindly. At the retreat, patients could work, rest, talk out their problems, and pray.

Reform in the United States started with the figure largely considered to be the father of American psychiatry, Benjamin Rush (1745-1813). Rush advocated for the humane treatment of the mentally ill, showing them respect, and even giving them small gifts from time to time. Despite this, his practice included treatments such as bloodletting and purgatives, the invention of the “tranquilizing chair,” and a reliance on astrology, showing that even he could not escape from the beliefs of the time.

Due to the rise of the moral treatment movement in both Europe and the United States, asylums became habitable and places where those afflicted with mental illness could recover. Its success was responsible for its decline. The moral treatment movement also fell due to the rise of the mental hygiene movement, which focused on the physical well-being of patients. Its main proponent in the United States was Dorothea Dix (1802-1887), a New Englander who observed the deplorable conditions suffered by the mentally ill while teaching Sunday school to female prisoners.

20th – 21st Centuries

The decline of the moral treatment approach in the late 19th century led to the rise of two competing perspectives – the biological or somatogenic perspective and the psychological or psychogenic perspective.

Biological or Somatogenic Perspective.

Recall that Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen said that mental disorders were akin to physical disorders and had natural causes. Though the idea fell into oblivion for several centuries it re-emerged in the late 19th century for two reasons.

First, German psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926), discovered that symptoms occurred regularly in clusters which he called syndromes. These syndromes represented a unique mental disorder with its own cause, course, and prognosis. In 1883 he published his textbook, Compendium der Psychiatrie (Textboook of Psychiatry), and described a system for classifying mental disorders that became the basis of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) that is currently in its 5th edition (published in 2013).

Secondly, in 1825, the behavioral and cognitive symptoms of advanced syphilis were identified to include a belief that everyone is plotting against you or that you are God (a delusion of grandeur), and were termed general paresis by French physician A.L.J. Bayle. In 1897, Viennese psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebbing injected patients suffering from general paresis with matter from syphilis spores and noted that none of the patients developed symptoms of syphilis, indicating they must have been previously exposed and were now immune. This led to the conclusion that syphilis was the cause of the general paresis. In 1906, August von Wassermann developed a blood test for syphilis and in 1917 a cure was stumbled upon. Julius von Wagner-Jauregg noticed that patients with general paresis who contracted malaria recovered from their symptoms. To test this hypothesis, he injected nine patients with blood from a soldier afflicted with malaria. Three of patients fully recovered while three others showed great improvement in their paretic symptoms. The high fever caused by malaria burned out the syphilis bacteria. Hospitals in the United States began incorporating this new cure for paresis into their treatment approach by 1925. Also noteworthy was the work of American psychiatrist John P. Grey. Appointed as superintendent of the Utica State Hospital in New York, Grey asserted that insanity always had a physical cause. As such, the mentally ill should be seen as physically ill and treated with rest, proper room temperature and ventilation, and a proper diet. The 1930s also saw the use of electric shock as a treatment method, which was stumbled upon accidentally by Benjamin Franklin while experimenting with electricity in the early 18th century. He noticed that after suffering a severe shock his memories had changed and in published work, suggested physicians study electric shock as a treatment for melancholia.

Psychological or Psychogenic Perspective.

The psychological or psychogenic perspective states that emotional or psychological factors are the cause of mental disorders and represented a challenge to the biological perspective. This perspective had a long history, but did not gain favor until the work of Viennese physician Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815). Influenced heavily by Newton’s theory of gravity, he believed that the planets also affected the human body through the force of animal magnetism and that all people had a universal magnetic fluid that determined how healthy they were.

He demonstrated the usefulness of his approach when he cured Franzl Oesterline, a 27-year old woman suffering from what he described as a convulsive malady. Mesmer used a magnet to disrupt the gravitational tides that were affecting his patient and produced a sensation of the magnetic fluid draining from her body. This removed the illness from her body and produced a near instantaneous recovery.

In reality, the patient was placed in a trancelike state which made her highly suggestible. With other patients, Mesmer would have them sit in a darkened room filled with soothing music, into which he would enter dressed in colorful robe and passed from person to person touching the afflicted area of their body with his hand or a special rod/wand. He successfully cured deafness, paralysis, loss of bodily feeling, convulsions, menstrual difficulties, and blindness. His approach gained him celebrity status as he demonstrated it at the courts of English nobility.

The medical community was hardly impressed. A royal commission was formed to investigate his technique but could not find any proof for his theory of animal magnetism. Though he was able to cure patients when they touched his “magnetized” tree, the result was the same when “non-magnetized” trees were touched. As such, Mesmer was deemed a charlatan and forced to leave Paris. His technique was called mesmerism and today, we know it as hypnosis.

The psychological perspective gained popularity after two physicians practicing in the city of Nancy in France discovered that they could induce the symptoms of hysteria in perfectly healthy patients through hypnosis and then remove the symptoms in the same way. The work of Hippolyte-Marie Bernheim (1840-1919) and Ambroise-Auguste Liebault (1823-1904) came to be part of what was called the Nancy School and showed that hysteria was nothing more than a form of self-hypnosis. In Paris, this view was challenged by Jean Charcot (1825-1893) who stated that hysteria was caused by degenerative brain changes, reflecting the biological perspective. He was proven wrong and eventually turned to their way of thinking.

The use of hypnosis to treat hysteria was also carried out by fellow Frenchman Pierre Janet (1859-1947), and student of Charcot, who believed that hysteria had psychological, not biological causes. Namely, these included unconscious forces, fixed ideas, and memory impairments. In Vienna, Josef Breuer (1842-1925) induced hypnosis and had patients speak freely about past events that upset them. Upon waking, he discovered that patients sometimes were free of their symptoms of hysteria. Success was even greater when patients not only recalled forgotten memories, but also relived them emotionally. He called this the cathartic method and our use of the word catharsis today indicates a purging or release, in this case, of pent up emotion.

By the end of the 19th century, it had become evident that mental disorders were caused by a combination of biological and psychological factors and the investigation of how they develop began. Sigmund Freud’s development of psychoanalysis followed on the heels of the work of Bruner, and others who came before him.

Current Views/Trends

Mental illness today

An article published by the Harvard Medical School in March 2014 called, “The Prevalent and Treatment of Mental Illness Today,” presented the results of the aforementioned National Comorbidity Study Replication of 2001-2003 including a sample of more than 9,000 adults. The results showed that nearly 46% of the participants had a psychiatric disorder at some time in their lives. The most commonly reported disorders were:

Major depression – 17%

Alcohol abuse – 13%

Social anxiety disorder – 12%

Conduct disorder – 9.5%

Also of interest was that women were more likely to have had anxiety and mood disorders while men showed higher rates of impulse control disorders. Comorbid anxiety and mood disorders were common and 28% reported having more than one co-occurring disorder (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005; Kessler, Demler, et al., 2005).

About 80% of the sample reported seeking treatment for their disorder, but with as much as a 10-year gap after symptoms first appeared. Women were more likely than men to seek help while whites were more likely than African and Hispanic Americans (Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005; Wang, Lane, et al., 2005). Care was sought primarily from family doctors, nurses, and other general practitioners (23%), followed by social workers and psychologists (16%), psychiatrists (12%), counselors or spiritual advisers (8%), and complementary and alternative medicine providers (CAMs; 7%).

In terms of the quality of the care, the article states: “Most of this treatment was inadequate, at least by the standards applied in the survey. The researchers defined minimum adequacy as a suitable medication at a suitable dose for two months, along with at least four visits to a physician; or else eight visits to any licensed mental health professional. By that definition, only 33% of people with a psychiatric disorder were treated adequately, and only 13% of those who saw general medical practitioners.”

Use of psychiatric drugs and deinstitutionalization.

Beginning in the 1950s, psychiatric or psychotropic drugs were used for the treatment of mental illness and made an immediate impact. Though drugs alone cannot cure mental illness, they can improve symptoms and increase the effectiveness of treatments such as psychotherapy. Classes of psychiatric drugs include antidepressants used to treat depression and anxiety, mood-stabilizing medications to treat bipolar disorder, antipsychotic drugs to treat schizophrenia, and anti-anxiety drugs to treat generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder.

A result of the use of psychiatric drugs was deinstitutionalization, or the release of patients from mental health facilities. This shifted resources from inpatient to outpatient care and placed the spotlight back on the biological or somatogenic perspective. When people with severe mental illness do need inpatient care, it is typically in the form of short term hospitalization

MODULE 2 - UNI AND MULTIDIMENSIONAL MODEL

In a general sense, a model is defined as a representation or imitation of an object. For mental health professionals, models help them understand mental illness since diseases such as depression cannot be touched or experienced firsthand. To be considered distinct from other conditions, a mental illness must have its own set of symptoms. But as you will see, the individual does not have to present with the entire range of symptoms to be diagnosed as having dysthymia, paranoid schizophrenia, avoidant personality disorder, or illness anxiety disorder. Five out of nine symptoms may be enough to label as having one of the disorders, for example.

Uni-Dimensional

This model of abnormality asserts that in order to effectively treat a mental disorder, its cause needs to be understood. This could be a single factor such as a chemical imbalance in the brain, relationship with a parent, socioeconomic status (SES), a fearful event encountered during middle childhood, or the way in which the individual copes with life’s stressors. This single factor explanation is called a uni-dimensional model. The problem with this approach is that mental disorders are not typically caused by a solitary factor, but multiple causes. Admittedly, single factors do emerge during the course of the person’s life, but as they arise they become part of the individual and in time, the cause of the person’s psychopathology is due to all of these individual factors.

Multi-Dimensional

In reality it is better to subscribe to a multi-dimensional model that integrates multiple causes of psychopathology and affirms that each cause comes to affect other causes over time. Uni-dimensional models alone are too simplistic to fully understand the etiology of mental disorders.

The following are the models being examined in this module:

1) Biological – Includes genetics, chemical imbalances in the brain, the functioning of the nervous system, etc.

2) Psychological – includes learning, personality, stress, cognition, self-efficacy, and early life experiences. We will examine several perspectives that make up the psychological model to include psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and humanistic-existential.

3) Sociocultural – includes factors such as one’s gender, religious orientation, race, ethnicity, and culture, for example.

Biopsychosocial Model - Most psychologists now recognize that abnormal behavior is caused by a combination of biological, psychological, and socio-cultural factors.

The Biological Model

The biological paradigm looks for biological abnormalities that might cause abnormal behavior. The roots of this approach can be traced to the discovery to the cause of general paresis (general paralysis), a syndrome characterized by a steady deterioration of both mental and physical disabilities, including symptoms such as delusions of grandeur and progressive paralysis. This severe physical and mental disorder is caused by syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease. Brain structure and chemistry, genes, hormonal imbalances, and viral infections as causes of mental disorder. The biological paradigm has successfully uncovered specific causes for some psychological disorders, particularly cognitive disorders. Like heart disease and cancer, most mental disorders appear to be “lifestyle disease” that result from the combination of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Brain Structure and Chemistry

Parts of the brain/neurotransmitters implicated for certain mental illnesses:

Low levels of serotonin are partially responsible for depression. New evidence suggests “nerve cell connections, nerve cell growth, and the functioning of nerve circuits have a major impact on depression. The amygdala, the thalamus, and the hippocampus are areas of the brain that play a significant role in depression.

Individuals with borderline personality disorder have been shown to have structural and functional changes in brain areas associated with impulse control and emotional regulation while imaging studies reveal differences in the frontal cortex and subcortical structures for those suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

Parkinson’s disease is a brain disorder which results in a gradual loss of muscle control and arises when cells in the substantia nigra, a long nucleus considered to be part of the basal ganglia, stop making dopamine.

People with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) have difficulty regulating serotonin.

Genes, Hormonal Imbalances, and Viral Infections

“Experts believe many mental illnesses are linked to abnormalities in many genes rather than just one or a few and that how these genes interact with the environment is unique for every person (even identical twins). That is why a person inherits a susceptibility to a mental illness and doesn’t necessarily develop the illness. Mental illness itself occurs from the interaction of multiple genes and other factors — such as stress, abuse, or a traumatic event — which can influence, or trigger, an illness in a person who has an inherited susceptibility to it”

Mental illness may run in families. Heritability of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression was documented.

Recent research has discovered that autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia all share genetic roots. They, “were more likely to have suspect genetic variation at the same four chromosomal sites. These included risk versions of two genes that regulate the flow of calcium into cells.”

Twin and family studies have shown that people with first-degree relatives suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are at higher risks to develop the disorder themselves. The same is true of borderline personality disorder.

Elevated levels of cortisol can cause an increased risk of depression.

Overproduction of the hormone melatonin can lead to Seasonal Affective Disorder.

Infections can cause brain damage and lead to the development of mental illness or an exacerbation of symptoms. For example, evidence suggests that contracting strep infection can lead to the development of OCD, Tourette’s syndrome, and tic disorder in children.

Influenza epidemics have also been linked to schizophrenia though more recent research suggests this evidence is weak at best.

Psychological Perspectives

Also called approaches or schools of thought, are interpretations of psychology that help professionals in the field understand an individual.

Psychodynamic Theory

Originating in the work of Sigmund Freud, the psychodynamic perspective emphasizes unconscious psychological processes (for example, wishes and fears of which we're not fully aware), and contends that childhood experiences are crucial in shaping adult personality.

The structure of personality.

According to Freud, our personality has three parts – the id, superego, and ego, and from these our behavior arises. The three parts of personality generally work together well and compromise, leading to a healthy personality, but if the conflict is not resolved, intrapsychic conflicts can arise and lead to mental disorders.

Both types of instincts, the Eros and the Thanatos, are sources of stimulation in the body and create a state of tension which is unpleasant, thereby motivating us to reduce them. Consider hunger, and the associated rumbling of our stomach, fatigue, lack of energy, etc., that motivates us to find and eat food. If we are angry at someone we may engage in physical or relational aggression to alleviate this stimulation.

The development of personality.

A person may become fixated at any stage of development, meaning they become stuck, thereby affecting later development and possibly leading to abnormal functioning, or psychopathology.

Fixation during the oral stage is linked to a lack of confidence, argumentativeness, and sarcasm.

During the anal stage, if parents are too lenient children may become messy or unorganized. If parents are too strict, children may become obstinate, stingy, or orderly.

A fixation during the phallic stage may result in low self-esteem, feelings of worthlessness, and shyness.

Ego-defense mechanisms

Are in place to protect us from pain but are considered maladaptive if they are misused and become our primary way of dealing with stress. They protect us from anxiety and operate unconsciously, also distorting reality.

Anton Mesmer employed mesmerism or hypnotism to people with hysteria - physical incapacity such as blindness, or paralysis.

Josef Breuer employed the cathartic method to his patient Anna O. Reliving an earlier emotional trauma and releasing emotional tension by expressing previously forgotten thoughts about the event, called catharsis.

Psychodynamic paradigm: abnormal behavior caused by unconscious mental conflicts rooted in early childhood experience; an outgrowth of the work and writings of Sigmund Freud.

Freud believed that psychological conflicts could be “converted” into physical symptoms

Alfred Adler’s individual psychology regarded people as inextricably tied to their society because he believed that fulfillment was found in doing things for the social good.

Helping individual patients change their illogical and mistaken ideas and expectations. Feeling and behaving better depend o thinking more rationally.

Classical conditioning can instill pathological fear. There is a possible relationship between classical conditioning and the development of certain disorders.

Operant conditioning principles can contribute to the development of certain disorders

Children of parents with phobias or substance abuse problems may acquire similar behavior patterns, in part through observation or modeling.

Cognitive approaches emphasize that how people construe themselves and the world is a major determinant of psychological disorders. By changing cognition, people can change their feelings, behaviors, and symptoms.

The Behavioral Model

Within the context of abnormal behavior or psychopathology, the behavioral perspective is useful because it says that maladaptive behavior occurs when learning goes awry. The good thing is that what is learned can be unlearned or relearned and behavior modification is the process of changing behavior.

The Cognitive Model

The work of George Miller, Albert Ellis, Aaron Beck, and Ulrich Neisser demonstrated the importance of cognitive abilities in understanding thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, and in the case of psychopathology, show that people can create their own problems by how they come to interpret events experienced in the world around them.

Schemas

Are sets of beliefs and expectations about a group of people, presumed to apply to all members of the group, and based on experience which can lead us astray or be false. These cognitive errors cause you to make certain assumptions about these individuals and might even affect how you interact with them.

Attributions

The idea that people are motivated to explain their own and other people’s behavior by attributing causes of that behavior to personal reasons or dispositional factors or to something outside the person or situational factors can lead us astray too. The fundamental attribution error occurs when we automatically assume a dispositional reason for another person’s actions and ignore situational factors. Then there is the self-serving bias which is when we attribute our success to our own efforts (dispositional) and our failures to outside causes (situational). These two cognitive errors affect how we see the world and our subjective well-being.

Maladaptive cognitions

Irrational thought patterns can be the basis of psychopathology. These unwanted, maladaptive cognitions, can be present as an excess such as with paranoia, suicidal ideation, or feelings of worthlessness; or as a deficit such as with self-confidence and self-efficacy. More specifically, cognitive distortions/maladaptive cognitions can take the following forms:

Overgeneralizing – You see a larger pattern of negatives based on one event.

Mind Reading – Assuming others know what you are thinking without any evidence.

What if? – Asking yourself what if? Something happens without being satisfied by any of the answers.

Blaming – You focus on someone else as the source of your negative feelings and do not take any responsibility for changing yourself.

Personalizing – Blaming yourself for negative events rather than seeing the role that others play.

Inability to disconfirm – Ignoring any evidence that may contradict your maladaptive cognition.

Regret orientation – Focusing on what you could have done better in the past rather than on making an improvement now.

Dichotomous thinking – Viewing people or events in all-or-nothing terms.

The Humanistic and Existential Perspectives

The humanistic perspective.

The humanistic perspective asserts that when people are made to feel that they can only be loved and respected if they meet certain standards, called conditions of worth, they experience conditional positive regard. Their self-concept is now seen as having worth only when these significant others approve and so becomes distorted, leading to a disharmonious state and psychopathology. Individuals in this situation are unsure what they feel, value, or need leading to dysfunction and the need for therapy.

The existential perspective

This approach stresses that abnormal behavior arises when we avoid making choices, do not take responsibility, and fail to actualize our full potential.

The Sociocultural Model

Outside of biological and psychological factors on mental illness, race, ethnicity, gender, religious orientation, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, etc. also play a role, and this is the basis of the sociocultural model.

Socioeconomic Factors

Low socioeconomic status has been linked to higher rates of mental and physical illness (Ng, Muntaner, Chung, & Eaton, 2014) due to persistent concern over unemployment or under-employment, low wages, lack of health insurance, no savings, and the inability to put food on the table, which then leads to feeling hopeless, helpless, and dependent on others. This situation places considerable stress on an individual and can lead to higher rates of anxiety disorders and depression.

Borderline personality disorder has also been found to be higher in people in Low Income Brackets (Tomko et al., 2012) and group differences for personality disorders have been found between African and European Americans (Ryder, Sunohara, and Kirmayer, 2015).

Gender Factors

Gender plays an important, though at times, unclear role in mental illness. It is important to understand that gender is not the cause of mental illness, though differing demands placed on males and females by society and their culture can influence the development and course of a disorder. Consider the following:

Rates of eating disorders are higher among women than men, though both genders are affected. In the case of men, muscle dysphoria is of concern and is characterized by extreme concern over being more muscular.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder has an earlier age of onset in girls than boys, with most people being diagnosed by age 19.

Females are at greater risk for developing an anxiety disorder than men.

ADHD is more common in males than females, though females are more likely to have inattention issues.

Boys are more likely to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Depression occurs with greater frequency in women than men.

Women are more likely to develop PTSD compared to men.

Rates of SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) are four times greater in women than men. Interestingly younger adults are more likely to develop SAD than older adults.

Consider this...

In relation to men: “Men and women experience many of the same mental disorders but their willingness to talk about their feelings may be very different. This is one of the reasons that their symptoms may be very different as well. For example, some men with depression or an anxiety disorder hide their emotions and may appear to be angry or aggressive while many women will express sadness. Some men may turn to drugs or alcohol to try to cope with their emotional issues.”

In relation to women: “Some women may experience symptoms of mental disorders at times of hormone change, such as perinatal depression, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and perimenopause-related depression. When it comes to other mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, research has not found differences in rates that men and women experiences these illnesses. But, women may experience these illnesses differently – certain symptoms may be more common in women than in men, and the course of the illness can be affected by the sex of the individual.”

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors also play a role in the development of mental illness.

In the case of borderline personality disorder, many people report experiencing traumatic life events such as abandonment, abuse, unstable relationships or hostility, and adversity during childhood.

Cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and drug use during pregnancy are risk factors for ADHD.

Divorce or the death of a spouse can lead to anxiety disorders.

Trauma, stress, and other extreme stressors are predictive of depression.

Malnutrition before birth, exposure to viruses, and other psychosocial factors are potential causes of schizophrenia.

SAD occurs with greater frequency for those living far north or south from the equator (Melrose, 2015). Horowitz (2008) found that rates of SAD are just 1% for those living in Florida while 9% of Alaskans are diagnosed with the disorder.

Multicultural Factors

Racial, ethnic, and cultural factors are also relevant to understanding the development and course of mental illness. Multicultural psychologists assert that both normal behavior and abnormal behavior need to be understood in relation to the individual’s unique culture and the group’s value system. Racial and ethnic minorities must contend with prejudice, discrimination, racism, economic hardships, etc. as part of their daily life and this can lead to disordered behavior (Lo & Cheng, 2014; Jones, Cross, & DeFour, 2007; Satcher, 2001), though some research suggests that ethnic identity can buffer against these stressors and protect mental health (Mossakowski, 2003

Current Paradigms in Psychopathology

Genetic Paradigm

All behavior is heritable to some degree. Genes do not operate in isolation from the environment. Throughout the lifespan, the environment shapes how our genes are expressed, and our genes also shape our environments.

Without genes, a behavior might not be possible. Without environment, genes could not express themselves and thus contribute to behavior

With respect to most mental illnesses, there is not one gene that contributes vulnerability.

Psychopathology is polygenic, meaning several genes, perhaps operating at different times during the course of development, turning themselves on and off as they interact with person’s environment is the essence of genetic vulnerability.

We do not inherit mental illness from our genes; we develop mental illness through the interaction of our genes with our environments.

Heritability refers to the extent to which variability in a particular behavior or disorder in a population can be accounted for by genetic factors.

a. Heritability estimates range from 0.0 to 1.0: the higher the number, the greater the heritability.

b. Heritability is relevant only for a large population of people, not a particular individual.

Environmental factors this refers that in a population (e.g., a large sample in a study), the variation in a particular disorder is understood as being attributed to a certain percent genes and a certain percent environment.

a. Shared environment factors include those things that members of the family have in common such as family income level, child-rearing practices, and parents’ marital status and quality

b. Nonshared environment (sometimes referred to as unique environment) factors are those things believed to be distinct among members of a family, such as relationships with friends or specific events unique to a person.

Life experience shapes how our genes are expressed, and our genes guide us in behaviors that lead to the selection of different experiences.

a. Gene-environment interaction means that a given person’s sensitivity to an environmental event is influences by genes.

b. Reciprocal gene-environment interaction explains how genes may promote certain types of environment. Genes may predispose us to seek out certain environments that then increase our risk for developing a particular disorder.

Neuroscience Paradigm

Mental disorders linked to aberrant (deviant) processes in the brain.

Several key neurotransmitters have been implicated in psychopathology, including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid.

Serotonin and dopamine may be involved in depression, mania and schizophrenia.

Norepinephrine may be involved in anxiety disorder and other stress-related conditions.

GABA may be involved in anxiety disorder

People with schizophrenia have been found to have enlarged ventricles of the brain.

The size of the hippocampus is reduced among some people with post traumatic stress disorder, depression, and schizophrenia.

Brain size among some children with autism expands at a much greater rate than it should in typical development

Cognitive Behavioral Paradigm

Problem behavior likely to continue if its reinforced.

Generally, problem behavior is thought to be reinforced by four possible consequences:

getting attention

escaping from tasks

generating sensory feedback

gaining access to desirable things or situations.

Individual with anxiety disorders tend to focus their attention on threatening or anxiety-producing events or situations in the environment.

Problem with schizophrenia have a hard time concentrating their attention for a period of time.

Systems Theory

An approach to integrating evidence on different contributions to abnormal behavior. You can think of systems theory as a synonym for the biopsychosocial model, but systems theory also embraces several key concepts. A central principle of systems theory is holism

Holism

The whole is more than the sum of its parts.

A human being is more than the sum of a nervous system, an organ system, a circulatory system, and so on. Similarly, abnormal psychology is more than the sum of inborn temperament, early childhood experiences, and learning history, or of nature and nurture. We can better appreciate the principle of holism if we contrast it with its scientific counterpoint, reductionism.

Reductionism attempts to understand problems by focusing on smaller and smaller units, viewing the possible unit as the true or ultimate cause.

For example, when depression is linked with depletion of certain chemicals in the brain, reductionists assume that brain chemistry is the cause of depression.

Systems theory reminds us, however that experiences such as having a negative view of the world or living in a prejudiced society may cause the changes in brain chemistry that accompany depression.

That is the “chemical imbalance in the brain” may be a product of adverse life experiences.

Different psychologist focus on different— but not necessarily inconsistent—levels of analysis in trying to understand the causes of abnormal behavior.

Each level of analysis in the biopsychosocial model views abnormal behavior through a different “lens”: microscope, magnifying glass, telescope.

one approach is not right, while others are wrong.

The lenses are just different, and each has a value for different purposes.

Causality

The cause of any one case of abnormal behavior occasionally can be located in one area of biological, psychological, or social functioning. Understanding the causes of psychological problems involves a multitude of casual influences, not a lone culprit.

Equifinality - the view that there are many routes to the same destination (or disorder).

Multifinality - says that the same event can lead to different outcomes.

Reciprocal causality - is the idea that causality works in both directions.

Because systems theory is complex, psychologists sometimes simplify their approach to understanding multiple influences on abnormal behavior by talking about the Diathesis-Stress Model.

Diathesis is a predisposition toward developing a disorder, e.g. an inherited tendency toward depression.

Stress is a difficult experience, e.g. the loss of a loved one through an unexpected death.

The Diathesis-Stress Model suggests that mental disorders develop only when a stress is added on top of a predisposition; neither the diathesis nor the stress alone is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Risk factors are events or circumstances that are correlated with an increased likelihood or risk of a disorder and potentially contribute to causing the disorder.

Diathesis-Stress Model: Integrative Paradigm

Diathesis-stress paradigm is an integrative paradigm that links genetic, neurobiological, psychological, and environmental factors.

It is a model that focuses on the interaction between a predisposition toward disease— the diathesis and environmental, or life disturbances— the stress.

Diathesis refers to a constitutional predisposition toward illness.

Characteristics or set of characteristics of a person that increases his/her chance of developing a disorder.

Diathesis increases the risk of developing a disorder but does not guarantee that a disorder will develop.

Stress meant to account for how a diathesis may be translated into an actual disorder.

Stress refers to a noxious or unpleasant environmental stimulus

Both diathesis and stress are necessary for the development of disorders

Psychopathology is unlikely to result from the impact of any single factor.

Developmental Psychopathology

Is a new approach to abnormal psychology that emphasizes the importance of developmental norms— age-graded averages— to determine what constitutes abnormal behavior.

Psychological disorders follow unique developmental patterns

Premorbid history, a pattern of behavior that precedes the onset of a disorder

Disorders may have a predictable course, or prognosis, for the future

by discussing premorbid adjustment and the course of different psychological disorders, we hope to present abnormal behavior as as a moving picture of development, not just a diagnostic snapshot.

MODULE 3 -CLINICAL ASSESSMENT, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT

In order for a mental health professional to be able to effectively help treat a client and

know that the treatment selected actually worked (or is working), he/she first must

engage in the clinical assessment of the client, or collecting information and

drawing conclusions through the use of observation, psychological tests, neurological

tests, and interviews to determine what the person’s problem is and what symptoms

he/she is presenting with.

This collection of information involves learning about the client’s skills, abilities, personality characteristics, cognitive and emotional functioning, social context in terms of environmental stressors that are faced, and cultural factors particular to them such as the language that is spoken or ethnicity.

It is a way of diagnosing and planning treatment

Evaluation of a patient's physical condition and prognosis based on information gathered

It involves the patient's medical history

Clinical assessment is not just conducted in the beginning of the process of seeking help but all throughout the process.

First, the need to determine if a treatment is even needed. By having a clear accounting of the person’s symptoms and how they affect daily functioning, to what extent the individual is adversely affected can be determined.

Second, to determine what treatment will work best. There are numerous approaches to treatment which include Behavior Therapy, Cognitive and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Humanistic- Experiential Therapies, Psychodynamic Therapies, Couples and Family Therapy, and biological treatments (psychopharmacology).

Finally, the need to know if the treatment employed worked. This will involve measuring before any treatment is used and then measuring the behavior while the treatment is in place.

Further, measuring of the behavior after the treatment ends is done to make sure symptoms of the disorder do not return.

THE PURPOSE OF CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Gather information from different sources

Case history of the client

Past and present life situations are also considered.

Comprehensive picture of the client's life, which helps in determining the diagnosis and course of treatment.

STEPS IN THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

Deciding What Is Being Assessed

The assessment process begins with a series of questions.

Is there a significant psychological problem?

What is the nature of this person's problem?

Is the problem primarily one of the emotion, thought, or behavior?

Determining All The Goals Of Assessment

The formulation of the psychologist's goal in a particular case. Goals may include diagnostic classification, determination of the severity of a problem, risk screening for future problems and evaluation of the effects of treatment, and prediction about the likelihood of certain types of future behavior.

Selecting Standards For Making Decision

Making decisions about the information and decisions and judgments require points of reference for comparison. Standards are used to determine if a problem exists, how severe a problem is, and whether the individual has evidenced improvement over a specified period of time.

Collecting Assessment Data

Psychologists must decide which of the many methods will be used to assess the client.

Includes the use of structured or unstructured clinical interviews, reviews of the individual's history from school or medical records, measurements of physiological functioning.

Making Decision

The information obtained in the psychological assessment process is valuable only to the extent that it can be used in making important decisions about the person or persons who are the focus of assessment.

The goals of assessment—diagnosis, screening, prediction, and evaluation of intervention—determine the types of decisions that are made.

The decisions that are made can have profound effects on people's lives. The process of making decisions is complex and the stakes are high. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that influence the decisions and judgments made by clinical psychologists and ways to optimize the quality of these decisions.

Communicating The Information

Typically takes the form of a written psychological report that is shared with the client, and professionals (physicians, teachers, and other mental health professionals), a court of law, or family members who are responsible for the client. The psychologists need to be accurate, to provide an explanation of the basis for their judgments, and to communicate free of technical jargon.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

To begin any type of treatment, the client/patient must be clearly diagnosed with a

mental disorder.

Clinical diagnosis is the process of using assessment data to determine if the pattern of symptoms the person presents with is consistent with the diagnostic criteria for a specific mental disorder set forth in an established classification system such as the DSM-5 or ICD-10.

Any diagnosis should have clinical utility meaning it aids the mental health professional determine prognosis, the treatment plan, and possible outcomes of treatment (APA, 2013). Receiving a diagnosis does not necessarily mean the person requires treatment. This decision is made based upon how severe the symptoms are, level of distress caused by the symptoms, symptom salience such as expressing suicidal ideation, risks and benefits of treatment, disability, and other factors (APA, 2013). Likewise, a patient may not meet full criteria for a diagnosis but require treatment nonetheless.

Symptoms that cluster together on a regular basis are called a syndrome. If they also follow the same, predictable course, they are characteristic of a specific disorder.

Assessment data are used to formulate a clinical diagnosis

Interview data, psychological test data, and reports from significant others provide information on the symptoms

Knowing the diagnosis for a person helps clinicians communicate with other health professionals & search the scientific literature for information on associated features such as etiology and prognosis

Diagnosis can provide an initial framework for a treatment plan

Classification System provide mental health professionals with an agreed upon list of disorders falling in distinct categories for which there are clear descriptions and criteria for making a diagnosis.

The most widely used classification system in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders currently in its 5th edition and produced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013). Alternatively, the World Health Organization (WHO) produces the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD) currently in its 10th edition with an 11th edition expected to be published.

THE DSM CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

A brief history of the DSM

The DSM 5 was published in 2013 and took the place of the DSM IV-TR (TR means Text Revision; published in 2000) but the history of the DSM goes back to 1844 when the American Psychiatric Association published a predecessor of the DSM which was a “statistical classification of institutionalized mental patients” and “…was designed to improve communication about the types of patients cared for in these hospitals” (APA, 2013, p. 6).

The DSM evolved through four major editions after World War II into a diagnostic classification system to be used psychiatrists and physicians, but also other mental health professionals. After the naming of a DSM-5 Task Force Chair and Vice-Chair in 2006, task force members were selected and approved by 2007 and work group members were approved in 2008. What resulted from this was an intensive process of “conducting literature reviews and secondary analyses, publishing research reports in scientific journals, developing draft diagnostic criteria, posting preliminary drafts on the DSM-5 Web site for public comment, presenting preliminary findings at professional meetings, performing field trials, and revisiting criteria and text”(APA, 2013)

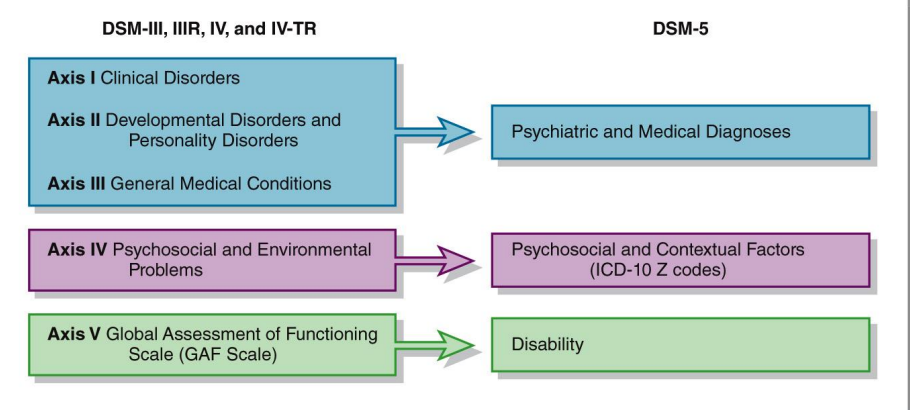

MULTIAXIAL CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM IN DSM-IV-TR AND DSM-5

KEY ELEMENTS OF DIAGNOSIS (DSM-5)

Diagnostic Criteria and Descriptors – Diagnostic criteria are the guidelines for making a diagnosis. When the full criteria are met, mental health professionals can add severity and course specifiers to indicate the patient’s current presentation. If the full criteria are not met, designators such as “other specified” or “unspecified” can be used. If applicable, an indication of severity (mild, moderate, severe, or extreme), descriptive features, and course (type of remission – partial or full – or recurrent) can be provided with the diagnosis. The final diagnosis is based on the clinical interview, text descriptions, criteria, and clinical judgment.

Subtypes and Specifiers – Subtypes denote “mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive phenomenological subgroupings within a diagnosis” (APA, 2013). For example, non-rapid eye movement sleep arousal disorders can have either a sleep walking or sleep terror type. Enuresis is nocturnal only, diurnal only, or both. Specifiers are not mutually exclusive or jointly exhaustive and so more than one specifier can be given. For instance, binge eating disorder has remission and severity specifiers. Somatic symptom disorder has a specifier for severity, if with predominant pain, and/or if persistent. Again the fundamental distinction between subtypes and specifiers is that there can be only one subtype but multiple specifiers.

Principal Diagnosis – A principal diagnosis is used when more than one diagnosis is given for an individual. It is the reason for the admission in an inpatient setting, or the reason for a visit resulting in ambulatory care medical services in outpatient settings. The principal diagnosis is generally the main focus of treatment.

Provisional Diagnosis – If not enough information is available for a mental health professional to make a definitive diagnosis, but there is a strong presumption that the full criteria will be met with additional information or time, then the provisional specifier can be used.

DSM-5 CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM OF MENTAL DISORDER

DISORDER CATEGORY | SHORT DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

Neurodevelopmental disorders | A group of conditions that arise in the developmental period and include intellectual disability, communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder, motor disorders, and ADHD |

Schizophrenia Spectrum | Disorders characterized by one or more of the following: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking and speech, disorganized motor behavior, and negative symptoms |

Bipolar and Related | Characterized by mania or hypomania and possibly depressed mood; includes Bipolar I and II, cyclothymic disorder |

Depressive | Characterized by sad, empty, or irritable mood, as well as somatic and cognitive changes that affect functioning; includes major depressive and persistent depressive disorders |

Anxiety | Characterized by excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances; Includes phobias, separation anxiety, panic attack, generalized anxiety disorder |

Obsessive-Compulsive | Characterized by obsessions and compulsions and includes OCD, hoarding, and body dysmorphic disorders |

Trauma- and Stressor- Related | Characterized by exposure to a traumatic or stressful event; PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorders |

Dissociative | Characterized by a disruption or disturbance in memory, identity, emotion, perception, or behavior; dissociative identity disorder, dissociative amnesia, and depersonalization/derealization disorder |

Somatic Symptom | Characterized by prominent somatic symptoms to include illness anxiety disorder somatic symptom disorder, and conversion disorder |

Feeding and Eating | Characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating or eating-related behavior to include bingeing and purging |

Elimination | Characterized by the inappropriate elimination of urine or feces; usually first diagnosed in childhood or adolescence |

Sleep-Wake | Characterized by sleep-wake complaints about the quality, timing, and amount of sleep; includes insomnia, sleep terrors, narcolepsy, and sleep apnea |

Sexual Dysfunctions | Characterized by sexual difficulties and include premature ejaculation, female orgasmic disorder, and erectile disorder |

Gender Dysphoria | Characterized by distress associated with the incongruity between one’s experienced or expressed gender and the gender assigned at birth |

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, Conduct | Characterized by problems in self-control of emotions and behavior and involve the violation of the rights of others and cause the individual to be in violation of societal norms; Includes oppositional defiant disorder, antisocial personality disorder, kleptomania, etc. |

Substance-Related and Addictive | Characterized by the continued use of a substance despite significant problems related to its use |

Neurocognitive | Characterized by a decline in cognitive functioning over time and the NCD has not been present since birth or early in life |

Personality | Characterized by a pattern of stable traits which are inflexible, pervasive, and leads to distress or impairment |

Paraphilic | Characterized by recurrent and intense sexual fantasies that can cause harm to the individual or others; includes exhibitionism, voyeurism, and sexual sadism |

THE ICD-10

In 1893, the International Statistical Institute adopted the International List of Causes of Death which was the first international classification edition. The World Health Organization was entrusted with the development of the ICD in 1948 and published the 6th version (ICD-6). The ICD-10 was endorsed in May 1990 by the 43rd World Health Assembly.

The WHO states: ICD is the foundation for the identification of health trends and statistics globally, and the international standard for reporting diseases and health conditions. It is the diagnostic classification standard for all clinical and research purposes. ICD defines the universe of diseases, disorders, injuries and other related health conditions, listed in a comprehensive, hierarchical fashion.

The ICD lists may types of diseases and disorders to include Chapter V: Mental and Behavioral Disorders. The list of mental disorders is broken down as follows:

Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use

Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders

Mood (affective) disorders

Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors

Disorders of adult personality and behavior

Mental retardation Disorders of psychological development

Behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence

Unspecified mental disorder

TREATMENT OF MENTAL DISORDER

Who Seeks Treatment?

Anyone can seek treatment. David Sack, M.D. (2013) writes in an article entitled, 5 Signs Its Time to Seek Therapy, published in Psychology Today, that “most people can benefit from therapy at least some point in their lives” and that though the signs you need to seek help are obvious at times, we often try “to sustain your busy life until it sets in that life has become unmanageable.” So when should we seek help?

First, if we feel sad, angry, or not like ourselves. We might be withdrawing from friends and families or sleeping more or less than we usually do.

Second, if we are abusing drugs, alcohol, food, or sex to deal with life’s problems. In this case, our coping skills may need some work.

Third, in instances when we have lost a loved one or something else important to us, whether due to a death or divorce, the grief may be too much to process.

Fourth, a traumatic event may have occurred such as abuse, a crime, an accident, chronic illness, or rape.

Finally, if you have stopped doing the things you enjoy the most. Sack (2013) says, “If you decide that therapy is worth a try, it doesn’t mean you’re in for a lifetime of “head shrinking.”

In fact, a 2001 study in the Journal of Counseling Psychology found that most people feel better within seven to 10 visits. In another study, published in 2006 in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88 percent of therapy-goers reported improvements after just one session.”

TREATMENT PLANNING

The process by which information about the client (including sociodemographic and psychological characteristics, diagnoses, and life context) is used in combination with the scientific literature on psychotherapy to develop a proposed course of action that addresses the client’s needs and circumstances

Problem identification, treatment goals, and treatment strategies and tactics (Case formulation) • For treatment to be efficient and focused, goals must be specified (Short-term goals & long term goals)

TREATMENT MONITORING & EVALUATION

Closely monitor the impact of treatment

Opportunity to reorient treatment efforts to avoid potential treatment failure

TREATMENTS

Psychopharmacology and Psychotropic drugs is a one option to treat severe mental illness is psychotropic medications. These medications fall under five major categories:

The antidepressants are used to treat depression, but also anxiety, insomnia, or pain.

Anti-anxiety medications help with the symptoms of anxiety.

Stimulants increase one’s alertness and attention and are frequently used to treat ADHD.

Antipsychotics are used to treat psychosis or, “conditions that affect the mind, and in which there has been some loss of contact with reality, often including delusions (false, fixed beliefs) or hallucinations (hearing or seeing things that are not really there).” They can be used to treat eating disorders, severe depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, OCD, ADHD, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Mood stabilizers are used to treat bipolar disorder and at times depression, schizoaffective disorder, and disorders of impulse control.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a procedure in which a brief application of electric stimulus is used to produce a generalized seizure. Patients are placed on a padded bed and administered a muscle relaxant to avoid injury during the seizures. ECT is used for conditions to include severe depression, acute mania, suicidality, and some forms of schizophrenia.

Psychosurgery is another option to treat mental disorders is to perform brain surgeries. Today’s techniques are much more sophisticated and have been used to treat schizophrenia, depression, and some personality and anxiety disorders.

Psychodynamic techniques is when Freud used three primary assessment techniques as part of psychoanalysis, or psychoanalytic therapy, to understand the personalities of his patients and to expose repressed material, which included free association, transference, and dream analysis.

free association involves the patient describing whatever comes to mind during the session. The patient continues but always reaches a point when he/she cannot or will not proceed any further. The patient might change the subject, stop talking, or lose his/her train of thought. Freud said this was resistance and revealed where issues were.

transference is the process through which patients transfer to the therapist attitudes he/she held during childhood. They may be positive and include friendly, affectionate feelings, or negative, and include hostile and angry feelings. The goal of therapy is to wean patients from their childlike dependency on the therapist.

dream analysis to understand a person’s inner most wishes. The content of dreams include the person’s actual retelling of the dreams, called manifest content, and the hidden or symbolic meaning, called latent content. In terms of the latter, some symbols are linked to the person specifically while others are common to all people.

Behavioral modification strategies these strategies arise from the different learning models postulated by Pavlov, Skinner, Bandura and other learning theorists. Behavior modification is the process of changing behavior. To begin, an applied behavior analyst will identify a target behavior, or behavior to be changed, define it, work with the client to develop goals, conduct a functional assessment to understand what the undesirable behavior is, what causes it, and what maintains it. Armed with this knowledge, a plan is developed and consists of numerous strategies to act on one or all of these elements – antecedent, behavior, and/or consequence.

Modeling techniques are used to change behavior by having subjects observe a model in a situation that usually causes them some anxiety. By seeing the model interact nicely with the fear evoking stimulus, their fear should subside. This form of behavior therapy is widely used in clinical, business, and classroom situations.

In terms of operant conditioning, strategies include antecedent manipulations, prompts, punishment procedures, differential reinforcement, habit reversal, shaping, and programming.

Flooding and desensitization are typical respondent conditioning procedures used with phobias.

Cognitive therapies like Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on exploring relationships among a person’s thoughts, feelings and behaviors. During CBT a therapist will actively work with a person to uncover unhealthy patterns of thought and how they may be causing self-destructive behaviors and beliefs. CBT attempts to identify negative or false beliefs and restructure them. Oftentimes someone being treated with CBT will have homework in between sessions where they practice replacing negative thoughts with more realistic thoughts based on prior experiences or record their negative thoughts in a journal. Some commonly used strategies include cognitive restructuring, cognitive coping skills training, and acceptance techniques.