SE Coastal Plain and Piedmont

SE Coastal Plain and Piedmont

Southeastern Evergreen Forest

Longleaf, Loblolly, and Slash Pine

Maritime forest

Cypress-gum

Pocosin and Atlantic whitecedar

Bottomland hardwood

Hydrology, microtopography, soils, and disturbance are major factors that separate forest types from the Coastal Plain.

Live oak (Quercus virginiana)

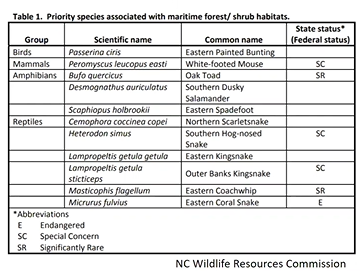

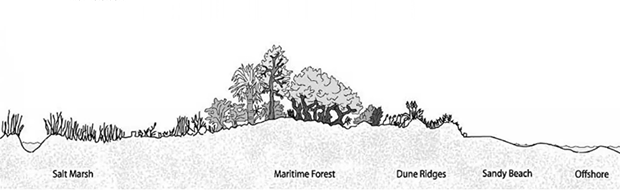

Maritime Forest

Forest structure

Species composition

Canopy

Live oak, loblolly pine, sand laurel oak

Shrubs

Yaupon holly, eastern redcedar, waxmyrtle

Understory/herb layer—sparse

Wildlife value

Environmental factors

Disturbance

Temperature/precipitation not selective factors

Sandy soils

Wind and storms

Salt spray and overwash (forms thick canopy layer to protect from salt spray)

Disturbance regime

Threats

Development

Climate change, especially sea level rise (ghost forests)

Which direction are we looking (north or south)?

North (ocean is East)

What are the key environmental factors that shape maritime forests?

Cypress-Gum Forests

Forest structure

often adjacent to bottomland sites

wettest of the coastal plain forest types; often flooded 3-6 months

Canopy of flood-tolerant species

Understory limited

No herbaceous layer

Species composition

Brownwater swamps (more widespread)

Baldcypress and Nyssa biflora (smaller leaves than blackgum)

Blackwater swamps

Blackcypress and Nyssa aquatica

Other species: Carolina ash, red maple, black gum

Environmental factors

Flooded in winter and early spring; flooded 3-6 months of the year

Flooding is the major selective factor that determines what species can survive

Disturbance regime

No cycle of regular natural disturbance; no fire

Hurricanes are periodic

Can be very long-lived

Threats

Climate change and saltwater intrusion

Carolina Bays, Pocosins, and Atlantic whitecedar

IMPORTANT: While the origin of the word “pocosin” is Algonquin, it does NOT translate to “swamp on a hill.” It is a generic term that refers to a wet area

Carolina bays describe some SE coastal plain geography; pocosins and Atlantic whitecedar are 2 community types found in Carolina Bays. Pocosins are closely related to Bay Forests.

Carolina Bays

Elliptical bays that either have open water or wetland forests

NW-SE orientation

Mostly organic soils and “bay” forests (either pocosin or Atlantic whitecedar)

Sandy rim (xeric longleaf pine forest) on the SE rims

Many have been drained and converted to agriculture

Ongoing debate about origin and formation

Carolina bays were thought to have formed through wind and weather patterns

Both types share seasonally wet, organic soils

The main difference (we think) is the disturbance regime

Pocosin and Bay Forests—moderate fire regime (about 10 year cycle)

Atlantic whitecedar—infrequent but catastrophic fire

Pocosin or Bay Forest

Environmental factors

Organic soils, from a few feet to 12 ft deep

Bays and depression ponds fill with partially decayed leaves, turns into “muck”

Organic soils hold water like a sponge

Forest structure

Canopy often open—also described as an evergreen shrub bog

Drier sites have trees and are called Bay Forests

Thick and evergreen midstory or understory of “bay” species

Often woven together with vines

Little herbaceous understory

Species composition

Canopy

Pond pine, Pinus serotina

Understory/shrub layer

Bay species: titi, sweetbay magnolia, swampbay, loblollybay

Vines weave everything together in a thick tangle

Disturbance - 10 year fire cycle

Pond pine: fire adapted: serotinous cones, epicormic branching, thick bark to withstand some fire

Threats

Former threats: ditching and draining for land conversion

Now: fire suppression, climate change

Atlantic Whitecedar Forests

Forest structure and disturbance regime

used to exist in pure, even-ages stands

remaining stands like this are rare; some found in the Albemarle/Pamlico penninsula in NC

even-aged structure suggest that catastrophic disturbance is needed for regeneration

Fire cycle through to be > 50 years

Large plant biomass = hot fires, clears seed bed

Selective cutting converted forests to gum and red maple

Species composition:

Atlantic whitecedar

Fire as a selective mechanism in the SE Coastal Plain

Frequent, low-intensity

longleaf pine

plants are adapted to survive fire

seed germination during non-fire season (fall)

grass stage

long, lush protective needles

loss of dead branches

thick bark

Infrequent, high-intensity

Atlantic whitecedar

plants can regenerate after fire

serotinous cones

abundant cone production; precocious (produce cones early)

short needles

dead branches retained (ladder)

thin bark

Longleaf pine, pondpine, and whitecedar are all shade intolerant with different adaptations

Bottomland Hardwood Forests

Forest structure

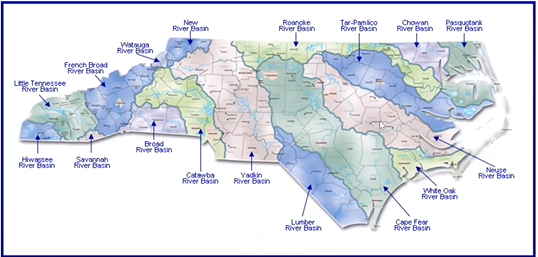

Geography: adjacent to brown or blackwater rivers, with periodic flooding

Closed canopy

Understory variable but uneven-aged, can be shrubby

Herb layer may or may not be rich

Species composition

Brownwater rivers

higher diversity; nutrient-rich sediment

Oaks dominant

Also green ash, sweetgum, American elm, musclewood

Blackwater rivers

Quercus laurifolia and Pinus taeda dominant

Understory: Magnolia virginiana, Persea palustris, Cyrilla racemiflora

Environmental factors

Brownwater rivers (also called redwater rivers)—originate in the Piedmont or Mountains, contain sediment

Blackwater rivers: originate in the Coastal Plain, lack sediment, but high in tannins—acidic, dark, and clear

Which type has a greater diversity of species? → Brownwater (blackwater is acidic and lacks sediment)

Wet and low-lying

Fires are not a factor (too wet to burn)

important habitat for birds like prothonotary warbler

Notice, also, that the species in brownwater Bottomland Hardwoods are common species of the Piedmont, and (not surprisingly), blackwater Bottomland Hardwoods have species that are more restricted to the Coastal Plain.

Disturbance regime

logged extensively for valuable timber

hurricanes

Threats

Habitat loss

conversion to agriculture

timber harvest

development

Invasive species

emerald ash borer