Chapter 5 Notes: Membranes (Page-by-Page)

Page 1

Chapter 5 – Membranes: The Interface Between Cells and Their Environment

Chapter Outline:

1. Membrane structure

2. Fluidity of membranes

3. Overview of membrane transport

4. Proteins that carry out membrane transport

5. Intercellular channels

6. Exocytosis and endocytosis

7. Cell junctions

Page 2

5.1 Membrane Structure

Section 5.1 Learning Outcomes

1) Describe the fluid-mosaic model of membrane structure and identify common membrane components in a figure

2) Give examples of the functions of biological membranes

3) Describe and identify different types of membrane proteins

Page 3

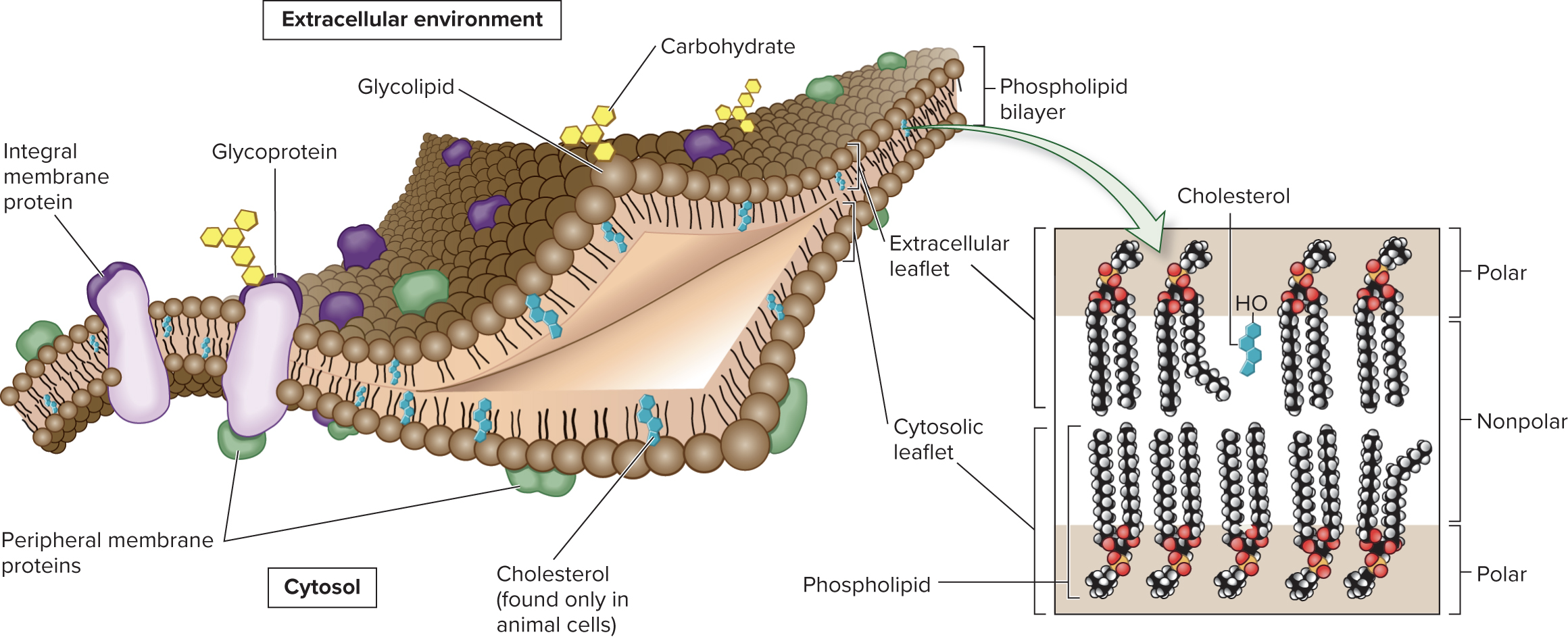

5.1 Membrane Structure

The 2 primary structural components of membranes are phospholipids and proteins; membranes perform many functions

Carbohydrates may be attached to membrane lipids and proteins, forming glycolipids and glycoproteins

Page 4

5.1 Membrane Structure Biological Membranes Are a Mosaic of Lipids, Proteins, and Carbohydrates

The phospholipid bilayer is the framework of the membrane

Phospholipids are amphipathic molecules; hydrophobic “tails” face in and hydrophilic “heads” face out

The two leaflets (halves of bilayer) are asymmetrical, with different amounts of each component

Ex: glycolipids are primarily found in the extracellular leaflet

Page 5

5.1 Membrane Structure Biological Membranes Are a Mosaic of Lipids, Proteins, and Carbohydrates

The fluid-mosaic model describes the membrane as a mosaic of lipid, protein, and carbohydrate molecules where the lipids and proteins can move relative to each other within the membrane

Page 6

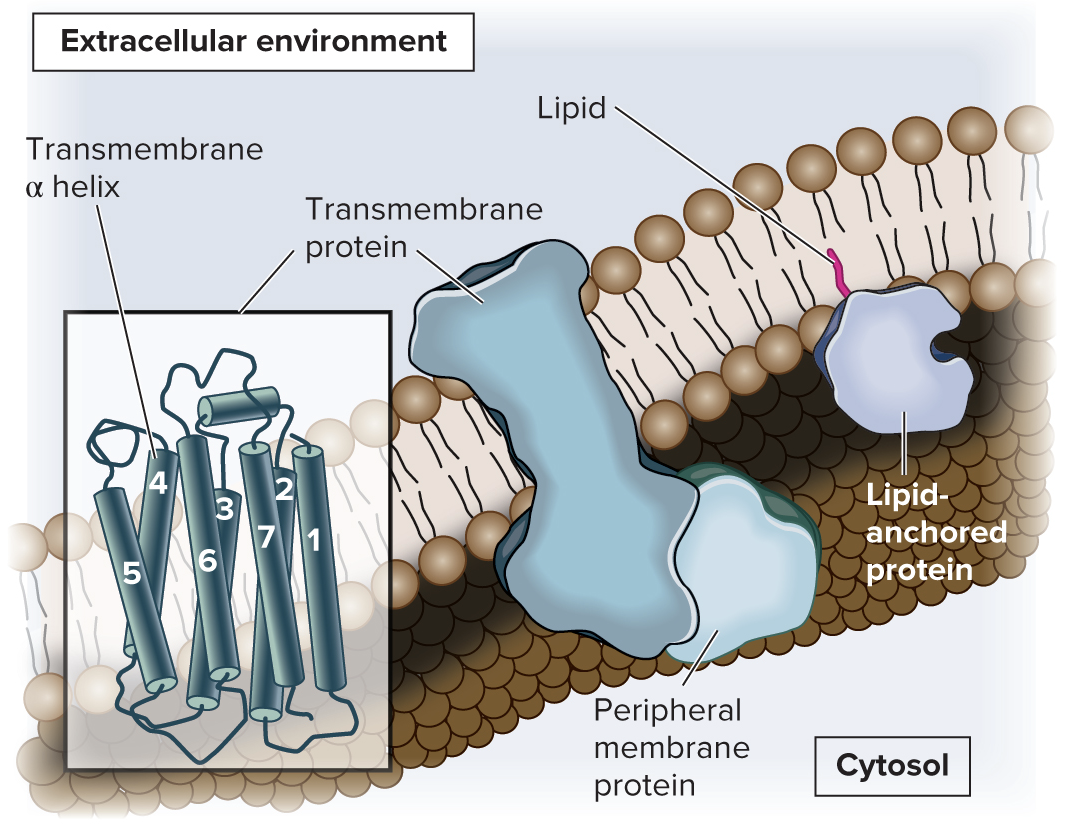

5.1 Membrane Structure Proteins Associate with Membranes in Three Ways

Although the phospholipid bilayer is the structural core, proteins carry out many important membrane functions

Proteins are categorized based on their association with the membrane (transmembrane, lipid-anchored, or peripheral proteins)

Transmembrane proteins span both leaflets of the membrane

In lipid-anchored proteins, an amino acid of the protein is covalently attached to a lipid

Peripheral membrane proteins are noncovalently bound to regions of other proteins or to the polar portions of phospholipids

Both transmembrane and lipid-anchored proteins are integral membrane proteins (have a portion that is integrated into the hydrophobic region of the membrane)

Page 7

5.2 Fluidity of Membranes

Section 5.2 Learning Outcomes

1) Describe the fluidity of membranes

2) Predict how fluidity will be affected by changes in lipid composition

3) Analyze the results of experiments indicating that certain membrane proteins can diffuse laterally within the membrane

Page 8

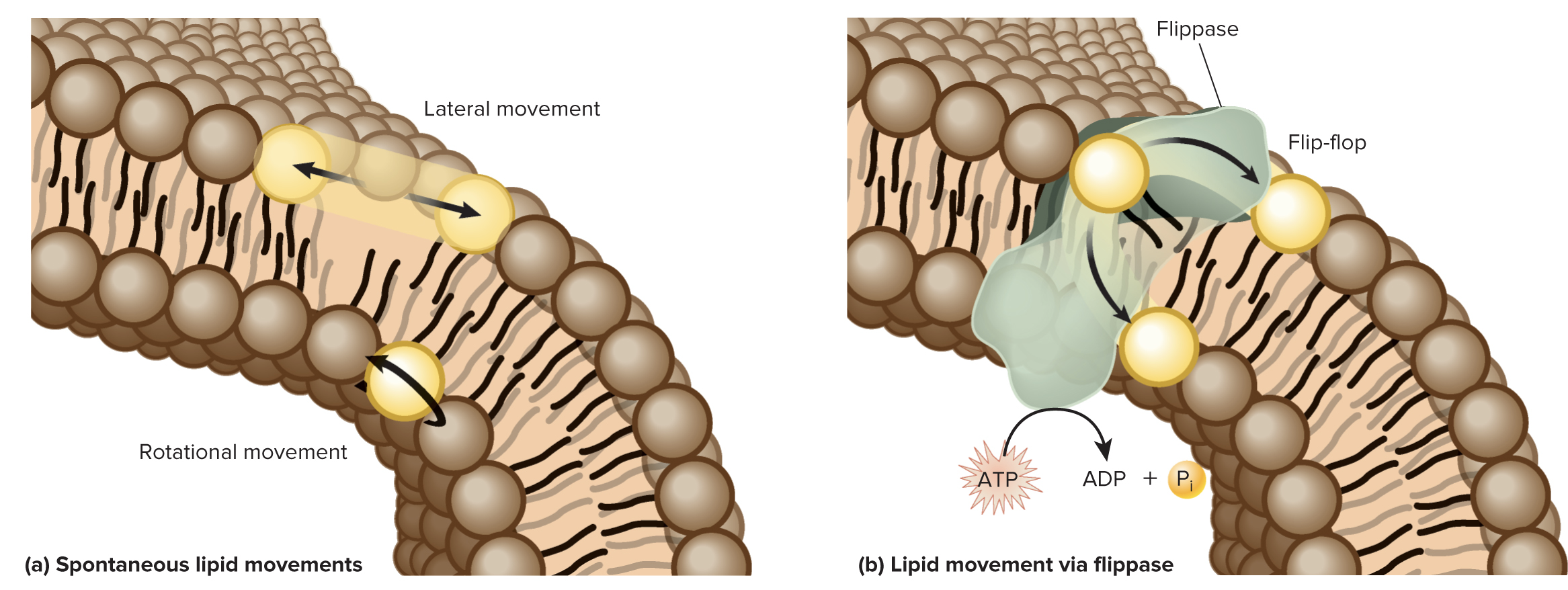

5.2 Fluidity of Membranes Membranes Are Semifluid

Membranes are not solid, rigid structures; rather membranes are semifluid as lipids and proteins can move in 2 dimensions (within the plane of the membrane)

A lipid can move the length of a bacterial cell in about 1 sec and move the length of an animal cell in 10-20 sec

“Flip-flop” of lipids between leaflets requires energy input and the action of a flippase enzyme.

Some lipids strongly associate with each other, forming lipid rafts that can anchor certain proteins

Page 9

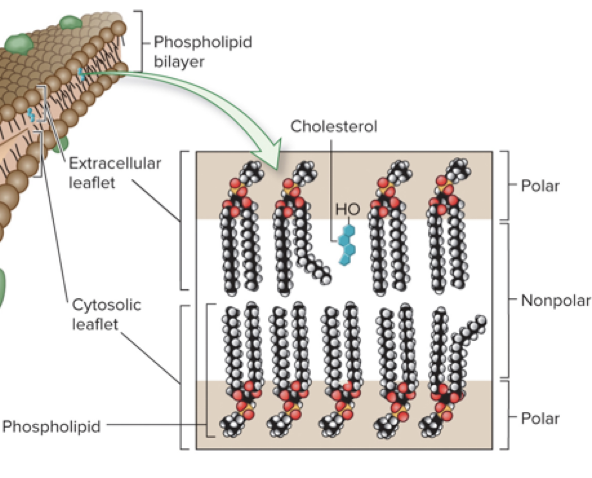

5.2 Fluidity of Membranes Lipid Composition Affects Membrane Fluidity

The biochemical properties of phospholipids affect fluidity

Length of the nonpolar tails (tails range from 14 to 24 carbons)

Shorter tails are less likely to interact → more fluid membrane

Presence of double bonds

A double bond puts a kink in the lipid tail, making it harder for neighboring tails to interact and making the bilayer more fluid

Presence of cholesterol (in animal cells)

Cholesterol tends to stabilize membranes

Effects vary depending on temperature

Page 10

5.2 Fluidity of Membranes Many Transmembrane Proteins Can Rotate and Move Laterally, but Some Are Restricted in Their Movement

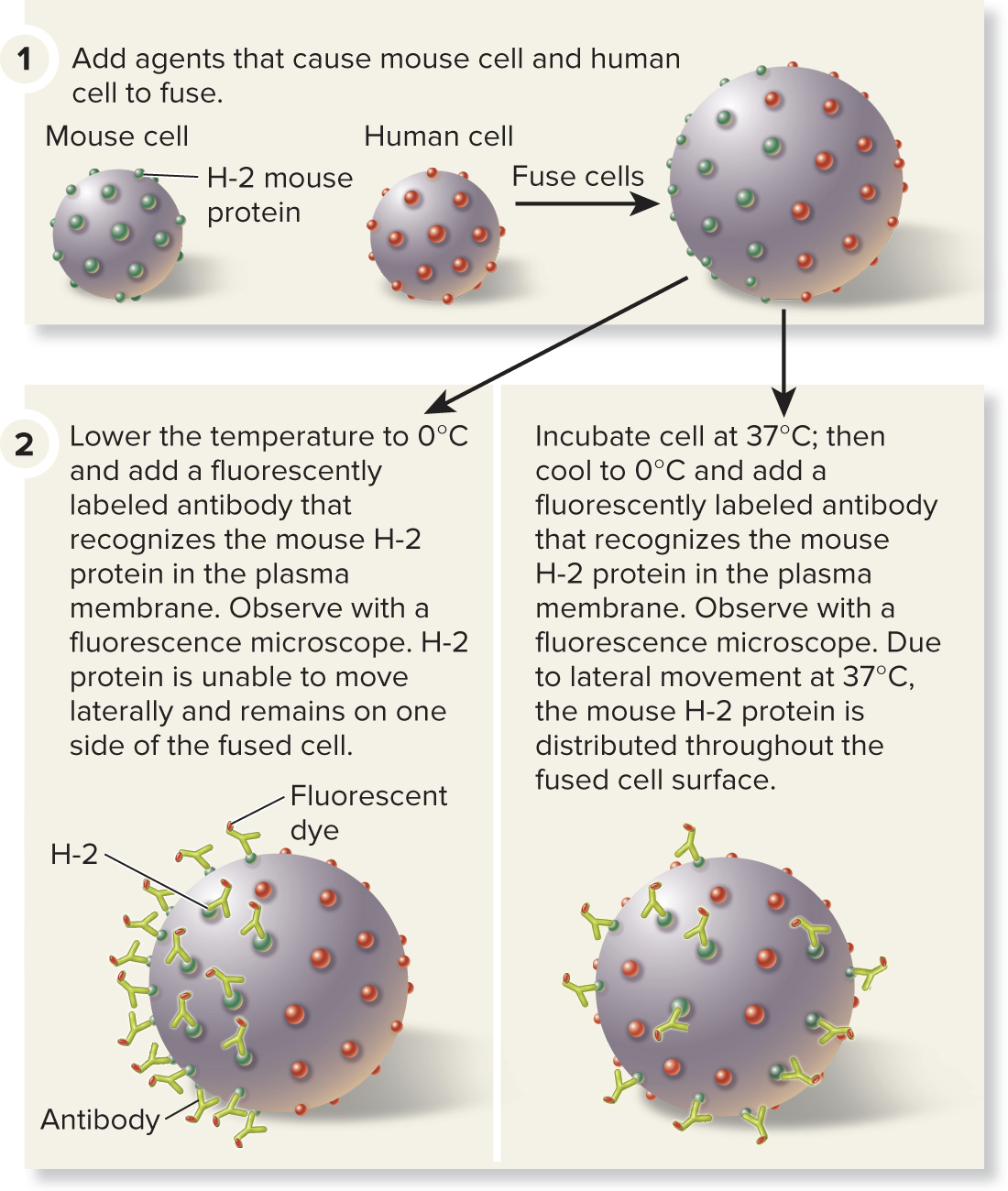

An experiment conducted in 1970 verified the lateral movement of transmembrane proteins:

Mouse and human cells were fused

Temperature treatment: 0°C (Freezing Point) or 37°C (Normal Body Temp.)

Mouse membrane protein H-2 fluorescently labeled

Cells at 0°C → label stays on mouse side

Cells at 37°C → label moves over entire fused cell

Page 11

5.2 Fluidity of Membranes Many Transmembrane Proteins Can Rotate and Move Laterally, but Some Are Restricted in Their Movement

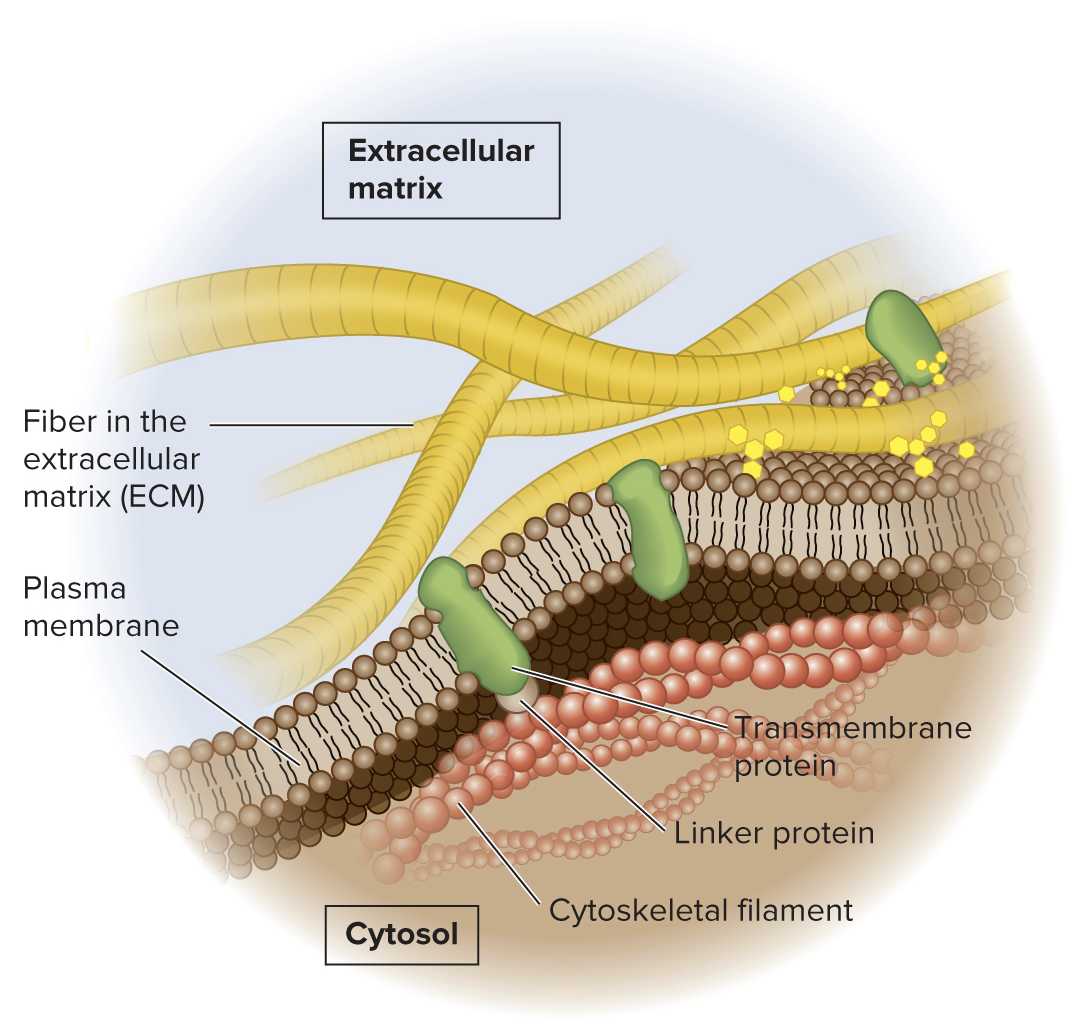

Depending on cell type, 10 to 70% of membrane proteins may be restricted in their movement

Integral membrane proteins may be bound to components of the cytoskeleton, which restricts the proteins from moving laterally

Membrane proteins may also be attached to molecules that are outside the cell, such as components of the ECM.

Page 12

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Section 5.3 Learning Outcomes

1) Compare and contrast simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, passive transport, and active transport

2) Explain the process of osmosis and how it affects cell structure

3) Predict the direction of water movement in response to a solute gradient

4) Sketch examples of simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, active transport, and osmosis

Page 13

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport

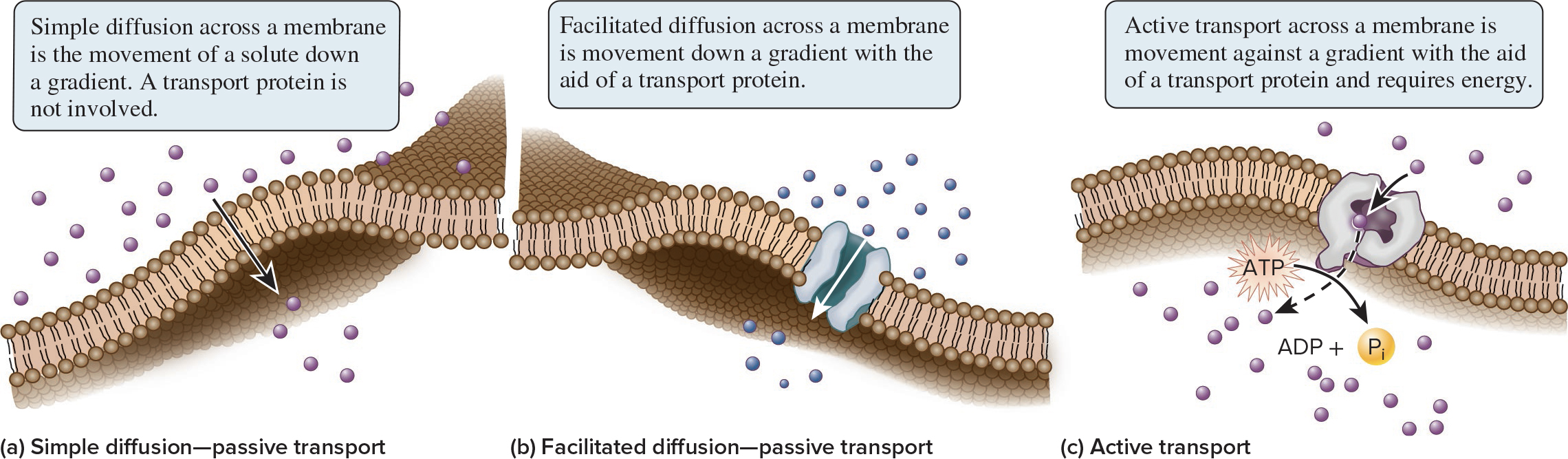

Membrane transport is a key function of membranes

The plasma membrane is selectively permeable, it allows the passage of some ions and molecules but not others

This ensures that essential molecules enter, metabolic intermediates remain, and waste products exit the cell

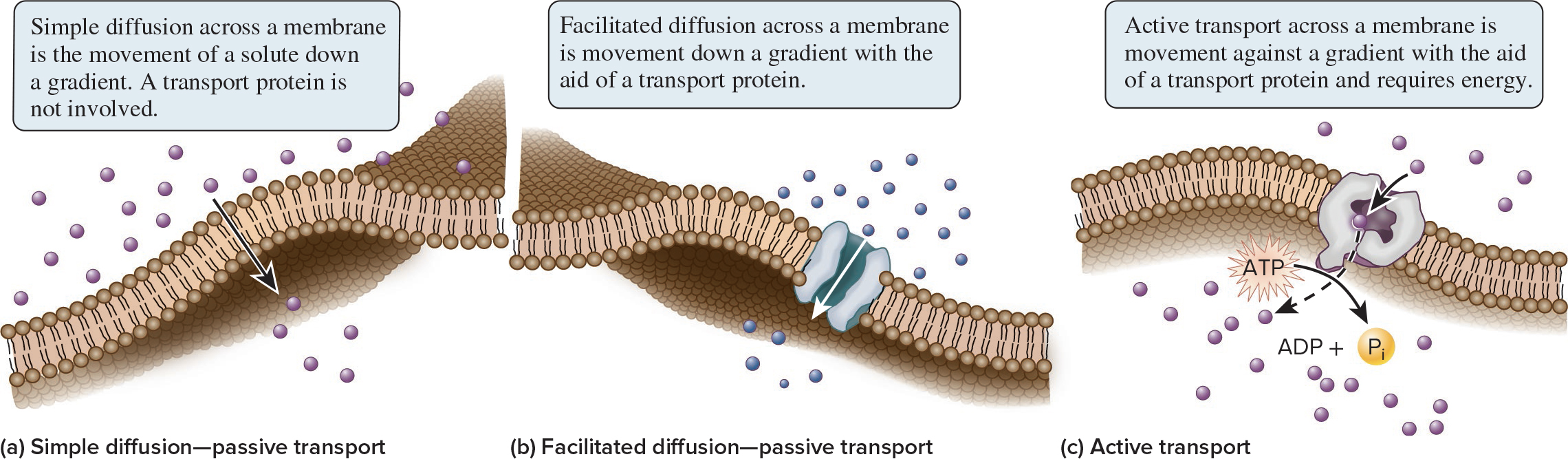

Substances can cross the membrane in 3 general ways: simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, or active transport

Passive transport does not require an input of energy whereas active transport does require energy

Page 14

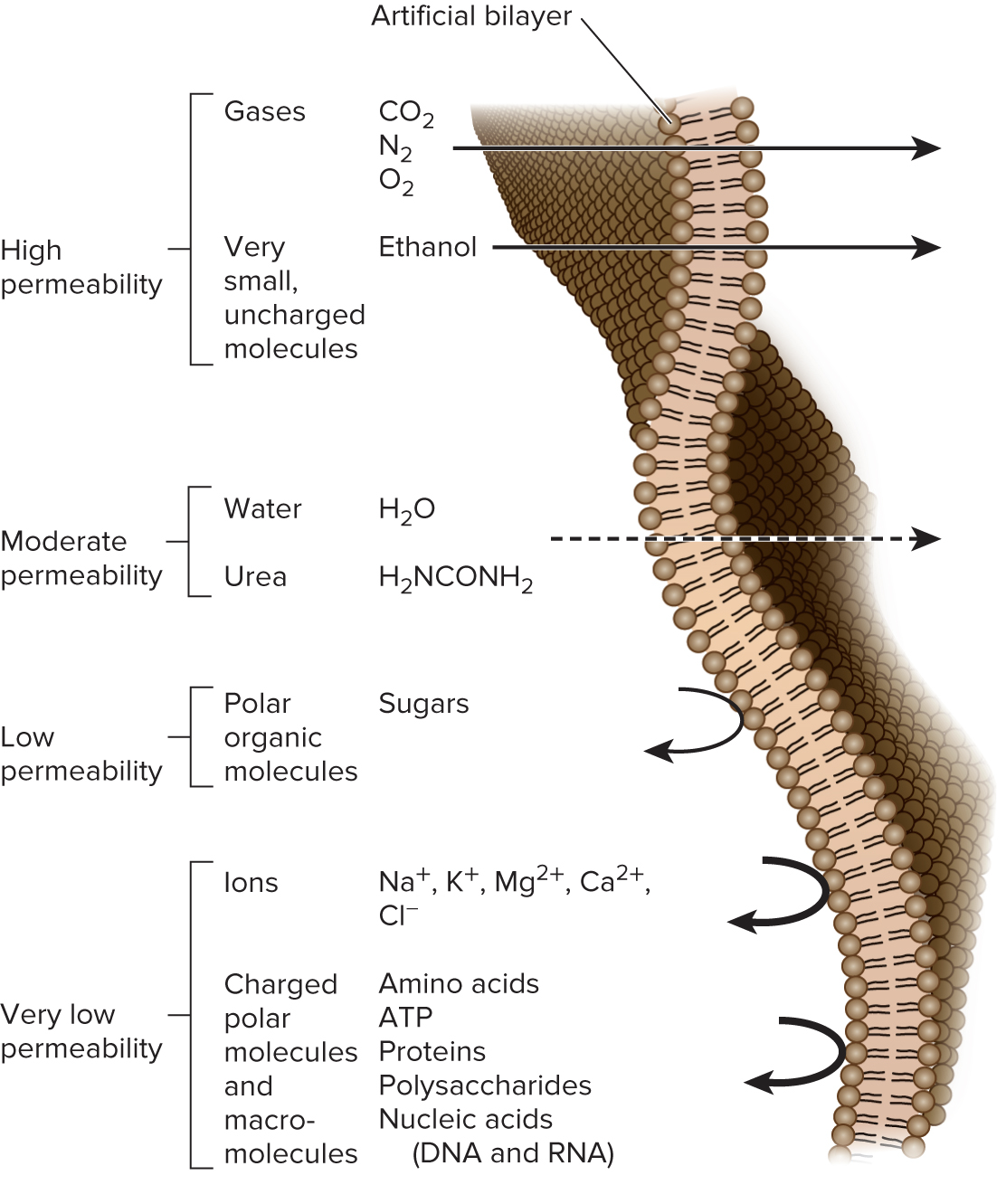

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport The Phospholipid Bilayer Is a Barrier to the Simple Diffusion of Hydrophilic Solutes

The phospholipid bilayer is a barrier to hydrophilic molecules and ions due to its hydrophobic interior

The ability of solutes to cross the bilayer by simple diffusion depends on:

Size → small molecules diffuse faster than large

Polarity → nonpolar molecules diffuse faster than polar

Charge → noncharged molecules diffuse faster than charged

Page 15

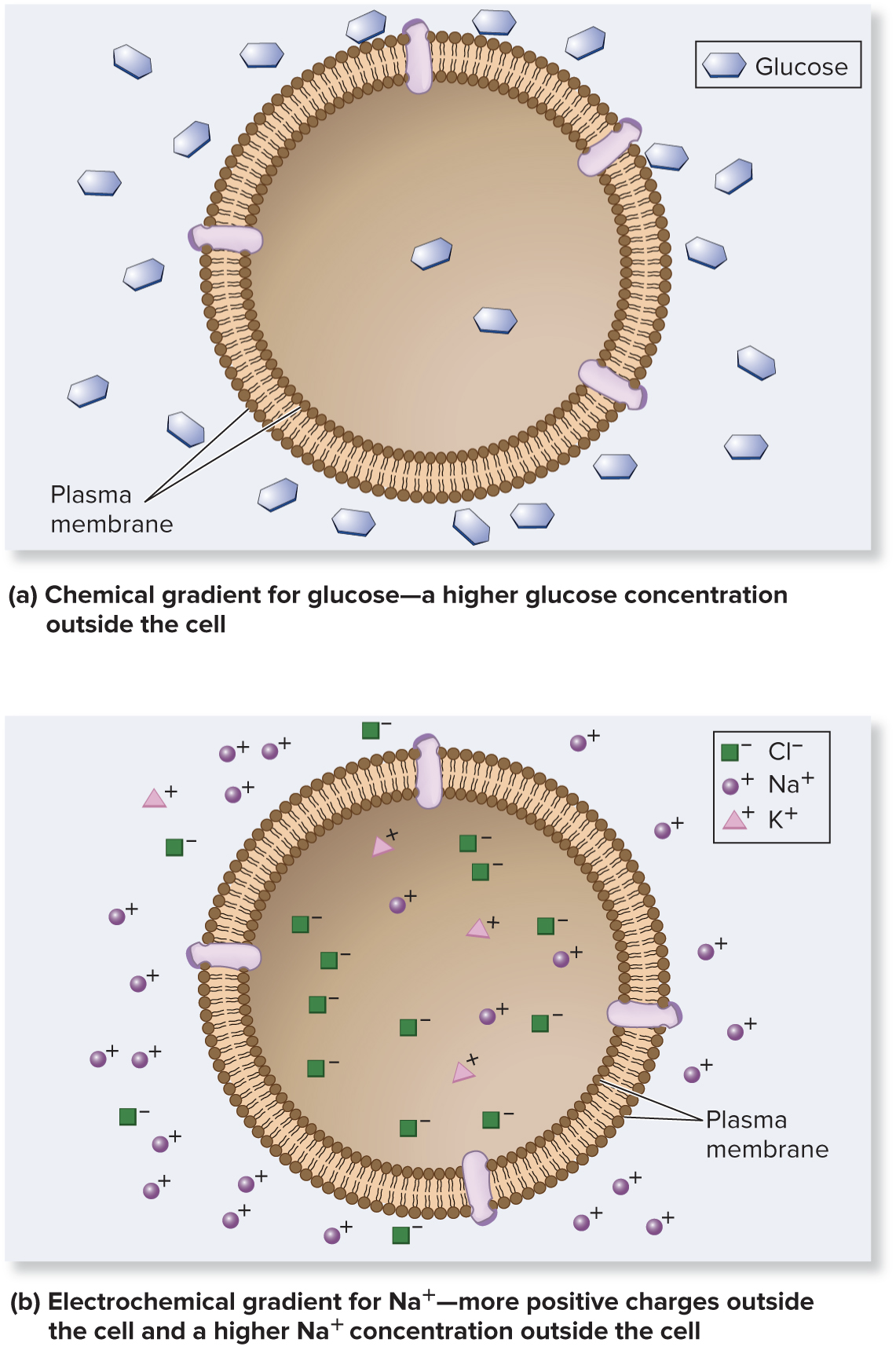

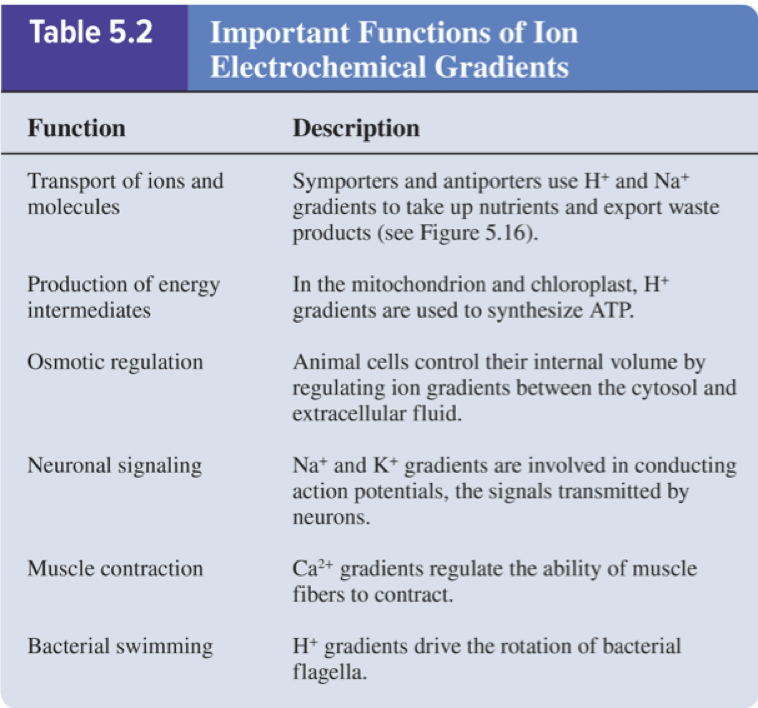

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Cells Maintain Gradients Across Their Membranes

Living cells maintain a relatively constant internal environment that is different from their external environment

A transmembrane gradient (concentration gradient) is present when the concentration of a solute is higher on one side of a membrane than the other

An electrochemical gradient is a dual gradient with both electrical and chemical components

Ion gradients

Page 16

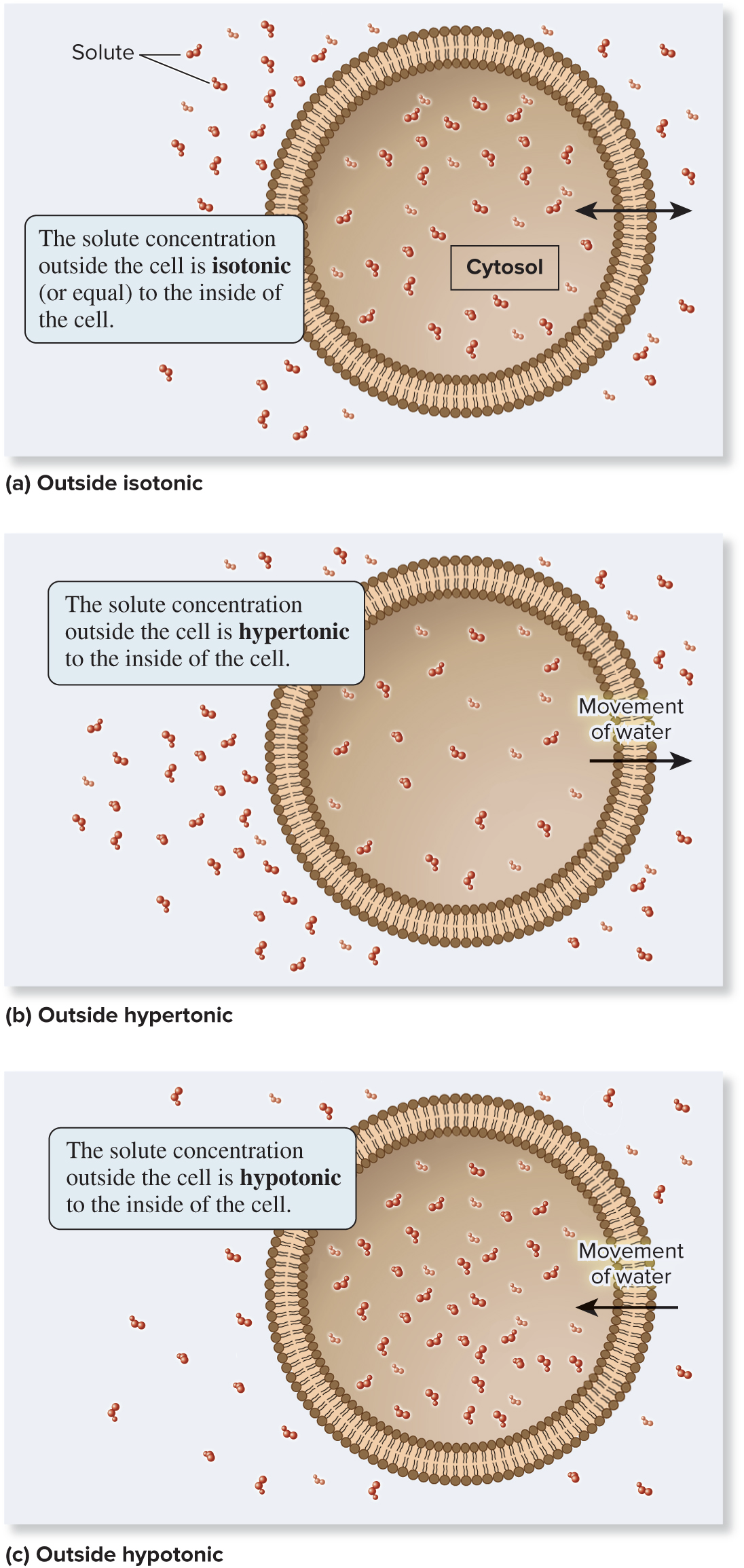

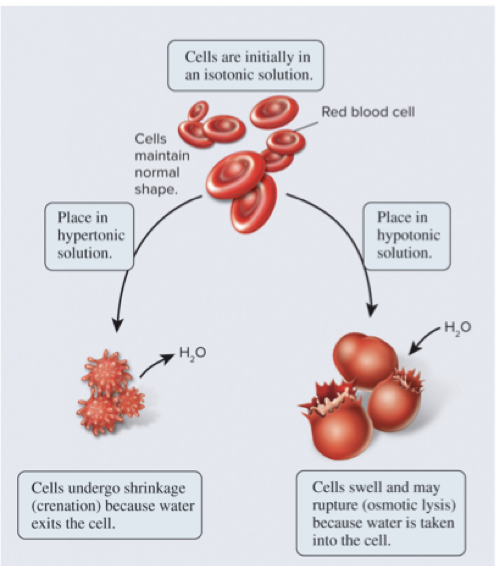

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Osmosis Is the Movement of Water Across a Membrane to Balance Solute Concentrations

Solute gradients affect the movement of water across membranes

There are 3 options for how solutions on opposite sides of a membrane relate to each other:

Isotonic (same solute concentration)

Hypertonic (more solute)

Hypotonic (less solute)

Typically, the solution outside the cell is compared to the solution inside the cell

Page 17

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Osmosis Is the Movement of Water Across a Membrane to Balance Solute Concentrations

There is an inverse relationship between solute concentration and water concentration

More solute → less free water

Less solute → more free water

Osmosis is the diffusion of water across a membrane

Water moves, from high to low, down its gradient: area of more water → area of less water which corresponds to hypotonic (less solute) → hypertonic (more solute)

Page 18

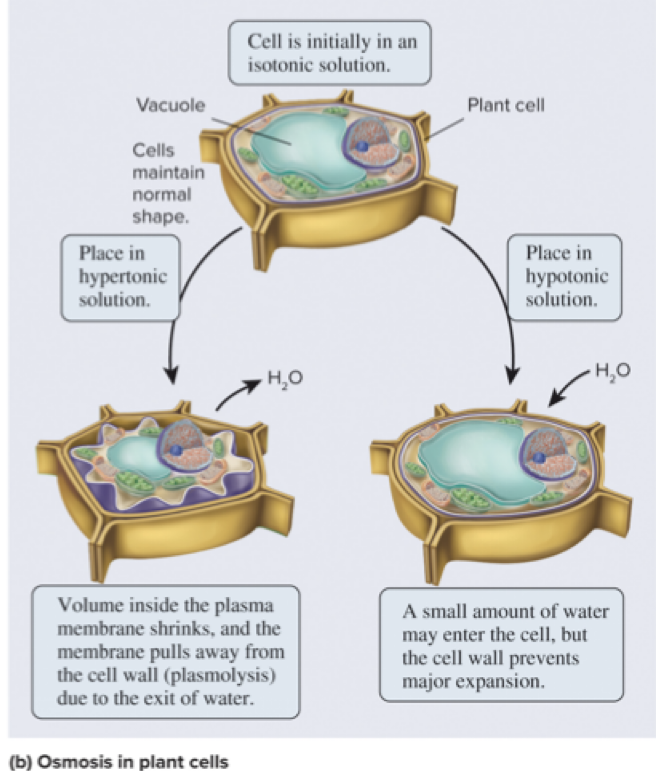

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Osmosis Is the Movement of Water Across a Membrane to Balance Solute Concentrations

How does osmosis affect cells with a rigid cell wall? bacteria, fungi, algae, plants

If the extracellular fluid is hypotonic, a plant cell will take up a small amount of water, but the cell wall prevents osmotic lysis

If the extracellular fluid is hypertonic, water will exit the cell

Page 19

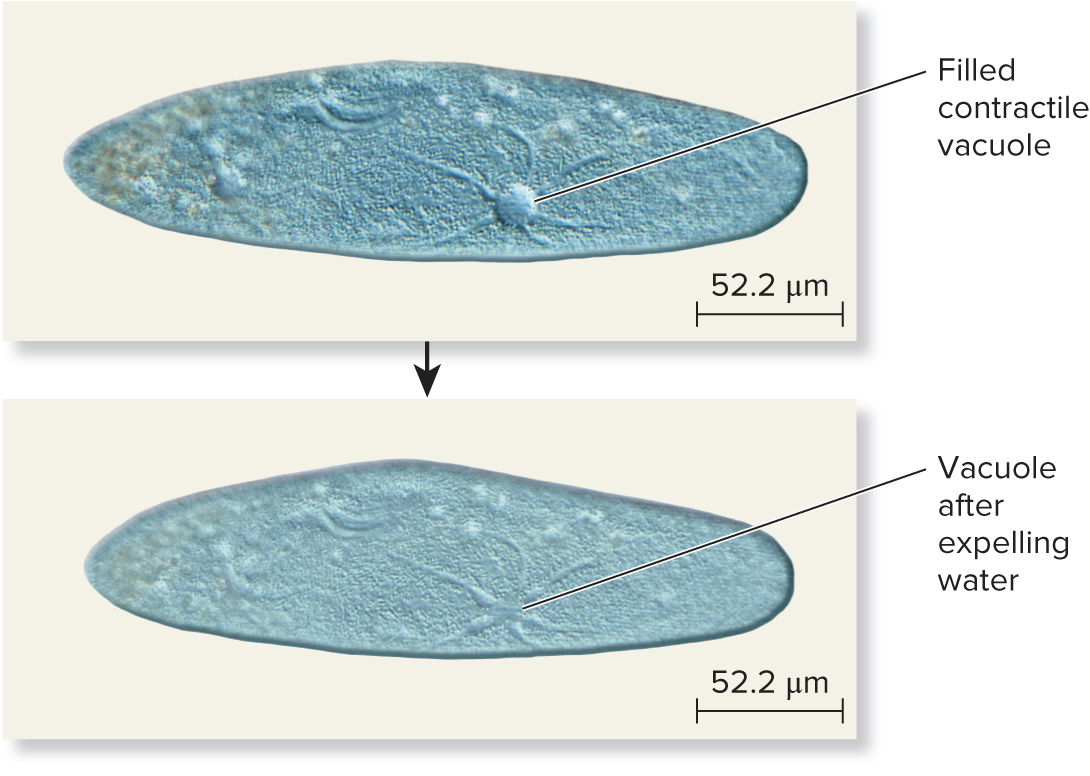

5.3 Overview of Membrane Transport Osmosis Is the Movement of Water Across a Membrane to Balance Solute Concentrations

Some freshwater microorganisms (ex: paramecium depicted below) live in extremely hypotonic environments

Water consistently moves into the cell by osmosis

Excess water is collected in a contractile vacuole and periodically expelled back to the environment

Page 20

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Section 5.4 Learning Outcomes

1) Outline the structural and functional differences between channels and transporters

2) Compare and contrast uniporters, symporters, and antiporters and sketch an example of each

3) Explain the concepts of primary and secondary active transport and sketch an example of each

4) Describe the structure and function of pumps

Page 21

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport

Transport proteins are transmembrane proteins that provide a passageway for the movement of ions and hydrophilic molecules across membranes

Two classes based on transport protein structure:

Channels

Transporters

Page 22

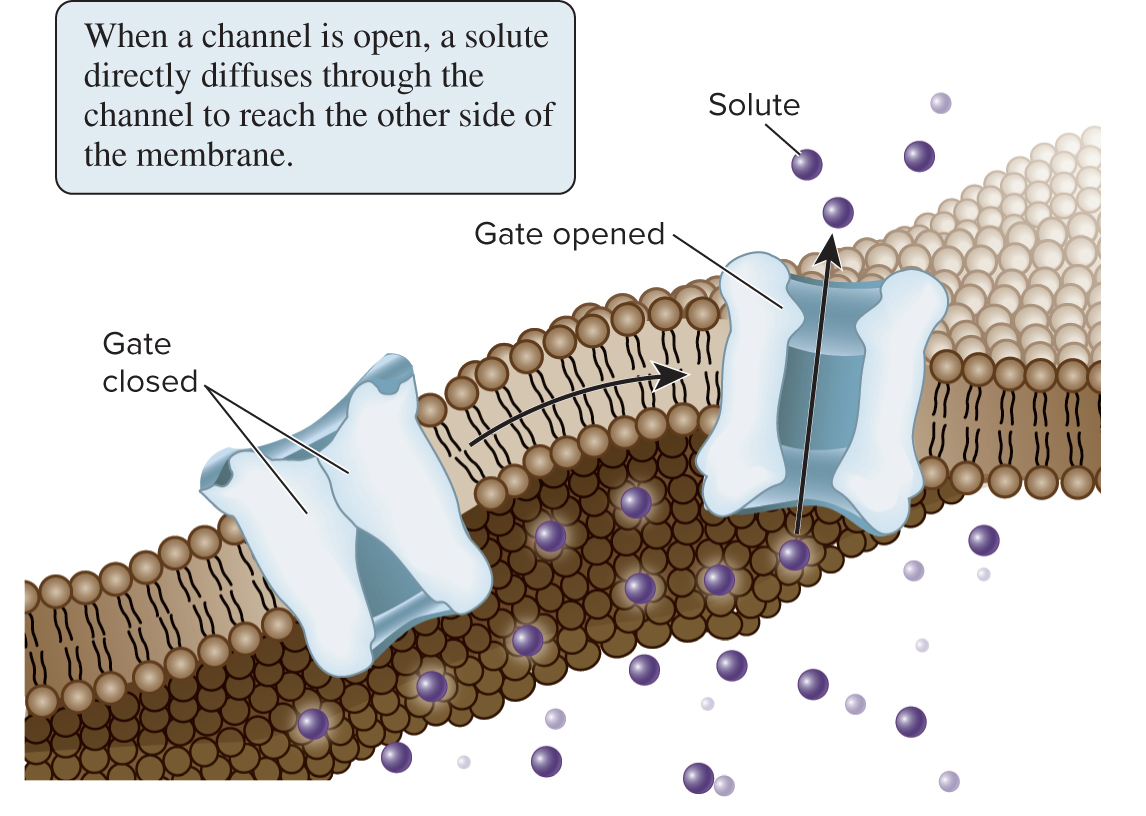

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Channels Provide Open Passageways for Solute Movement

Channels provide an open passageway that can facilitate the diffusion of hydrophilic molecules or ions

Most channels are gated, meaning they transition between open and closed states based on regulatory signals

Ex: some channels are regulated through interactions with other small molecules like hormones or neurotransmitters

In contrast to transporters, channels do not have a specific binding site (pocket) for their solutes

Page 23

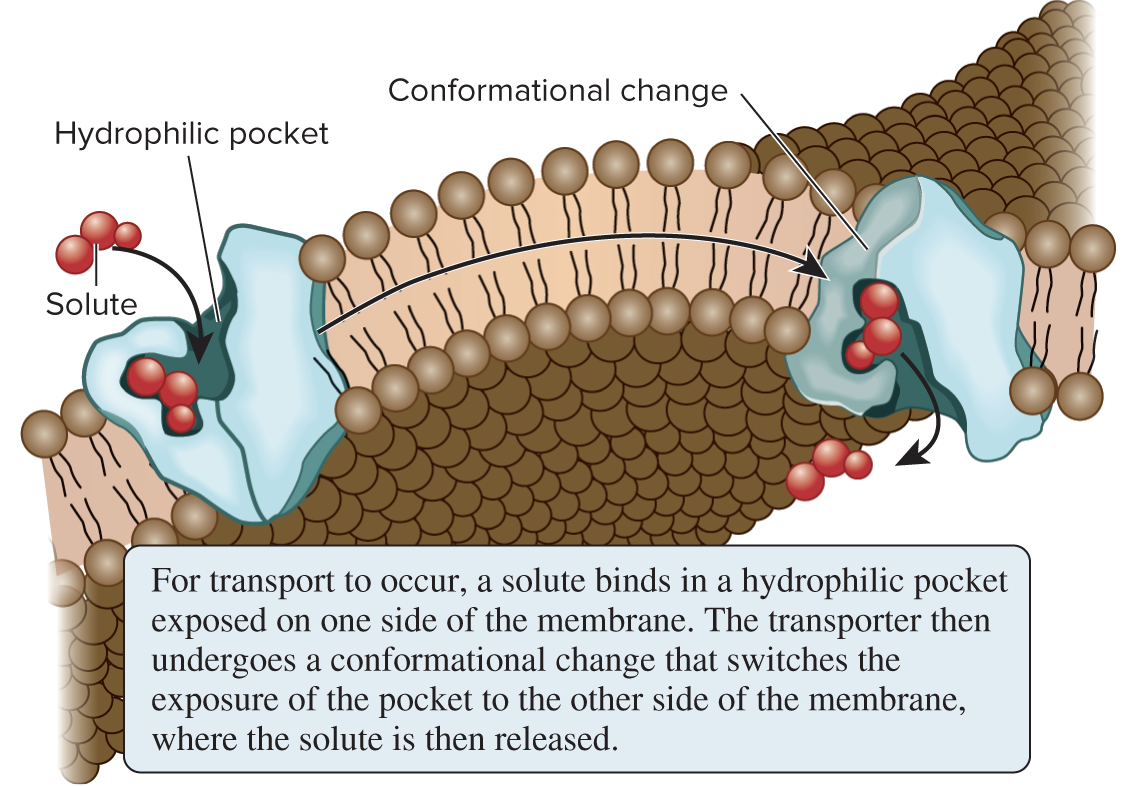

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Transporters Bind Their Solutes and Undergo Conformational Changes

Transporters (aka carriers) bind their solutes in a hydrophilic pocket and undergo a conformational change that switches the exposure of the pocket from one side of the membrane to the other

Transporters provide the principal pathway for uptake of organic molecules, such as sugars, amino acids, and nucleotides; they are also involved in expelling various waste materials out of cells

Page 24

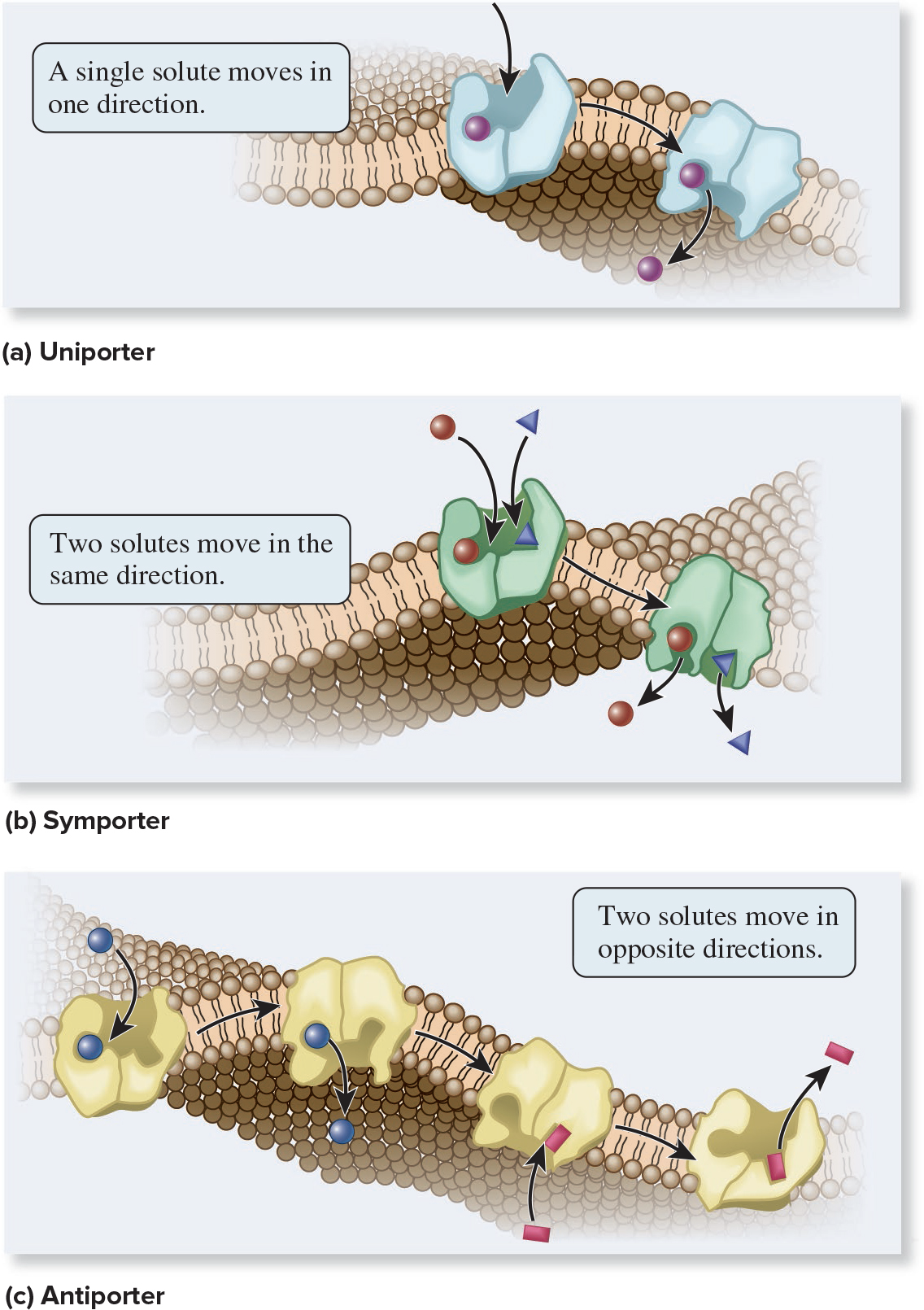

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Transporters Bind Their Solutes and Undergo Conformational Changes

Transporters are named according to the number of solutes they bind and the direction in which they transport those solutes:

Uniporter

Symporter

Antiporter

Page 25

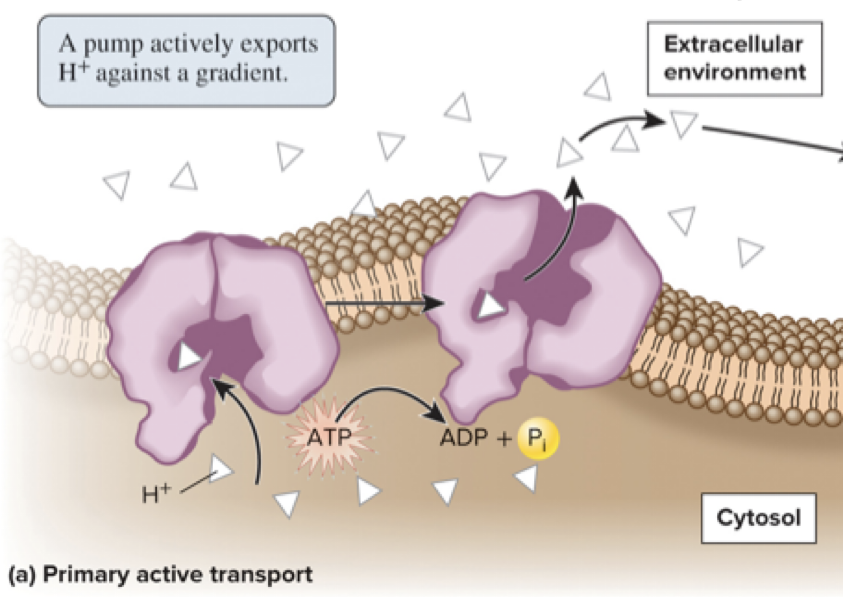

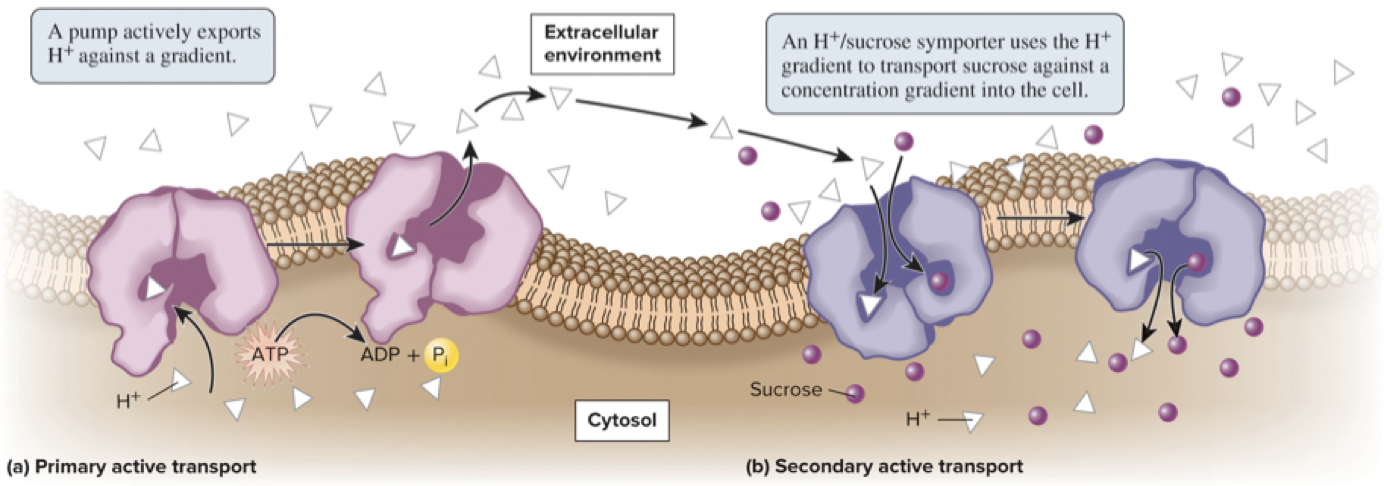

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Active Transport Is the Movement of Solutes Against a Gradient

Active transport is the movement of a solute across a membrane against its gradient (from lower to higher concentration area)

Energetically unfavorable and requires the input of energy

There are 2 general types: primary and secondary active transport

Primary active transport directly uses energy (typically released from ATP hydrolysis) to transport a solute against its gradient

Page 26

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport Active Transport Is the Movement of Solutes Against a Gradient

Secondary active transport involves the use of energy stored in a pre-existing gradient to drive the active transport of another solute

Ex: the H+/sucrose symporter depicted below uses the energy of the H+ gradient to move sucrose against its gradient

H+ is used by many symporters in bacteria, fungi, algae, and plant cells whereas Na+ use is prevalent in animal cells

Page 27

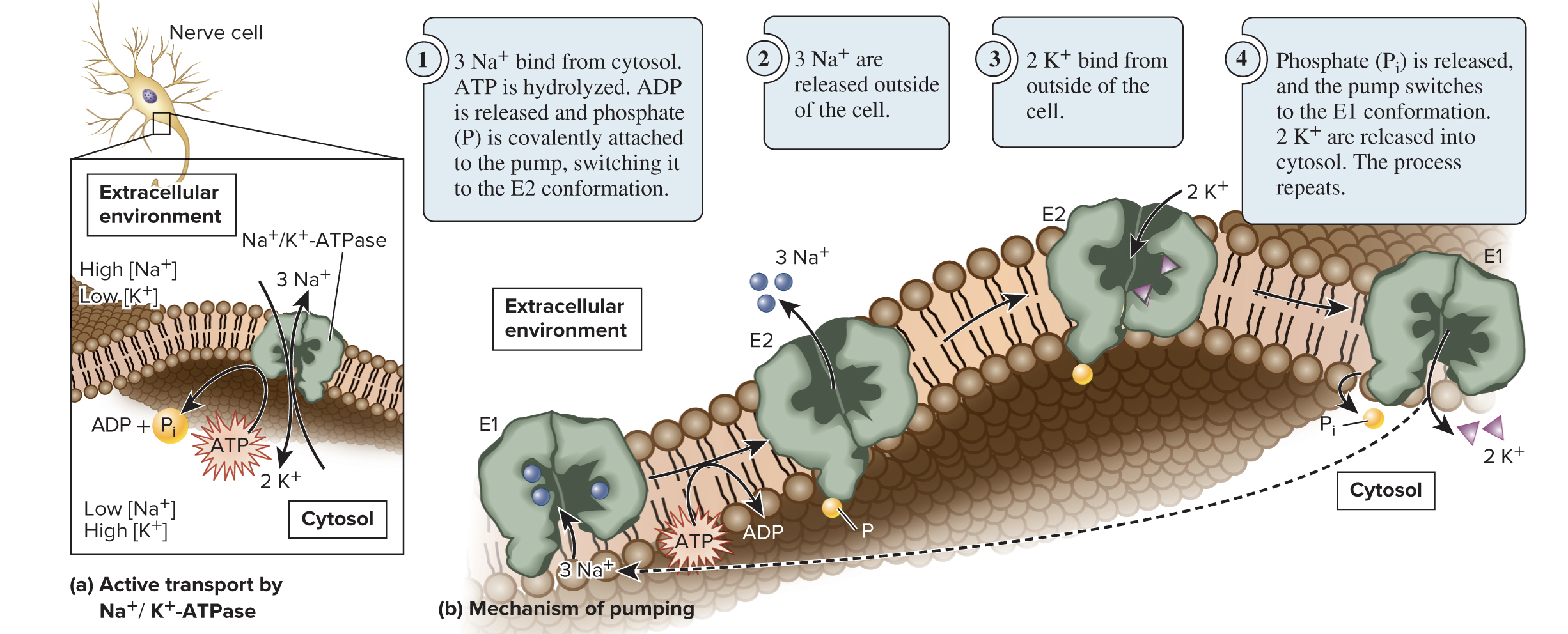

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport ATP-Driven Ion Pumps Generate Ion Electrochemical Gradients

The Na+/K+-ATPase is an antiporter that actively transports Na+ and K+ against their gradients using the energy from ATP hydrolysis

3 Na+ are exported for every 2 K+ imported into a cell

The transporter alternates between 2 confirmations: E1 (binding sites are accessible from the cytosol) and E2 (binding sites are accessible from the extracellular environment)

Page 28

5.4 Proteins That Carry Out Membrane Transport ATP-Driven Ion Pumps Generate Ion Electrochemical Gradients

Cells have many different types of ion pumps in their membranes

Ion pumps maintain ion gradients that drive many important cellular processes:

Cells invest a tremendous amount of their energy (up to 70%) into ion pumping

Page 29

5.5 Intercellular Channels Section 5.5 Learning Outcomes

1) Compare and contrast the structure and function of gap junctions and plasmodesmata

Page 30

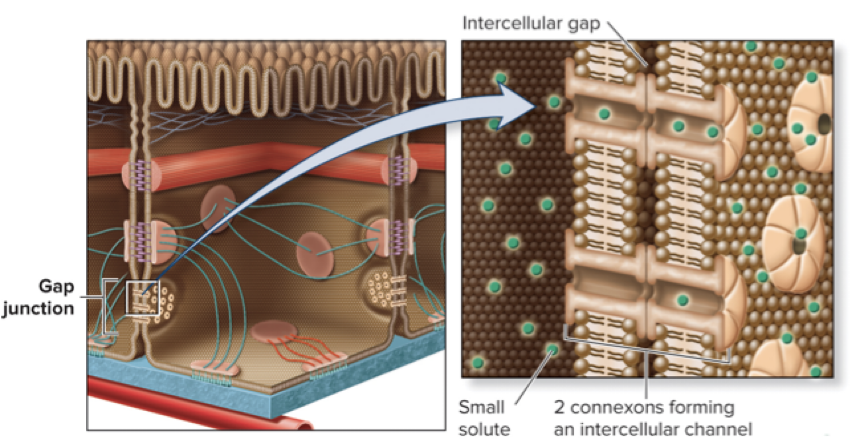

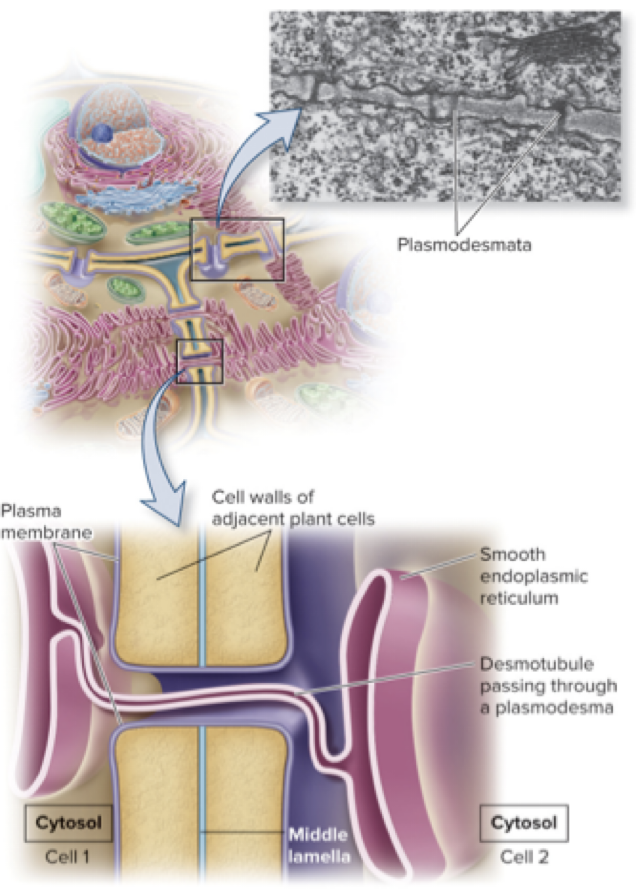

5.5 Intercellular Channels

In addition to the channels and transporters previously discussed, the cells of multicellular organisms may also have intercellular channels that allow direct movement of substances between adjacent cells

Gap junctions can connect animal cells

Plasmodesmata can connect plant cells

Page 31

5.5 Intercellular Channels Gap Junctions Between Animal Cells Provide Passageways for Intercellular Transport

Gap junctions are abundant in tissues where cells need to communicate with each other (ex: cardiac muscle)

Six membrane proteins called connexins assemble to form a connexon; connexons of adjacent cells align to form a channel

A cluster of many connexons is a gap junction

Gap junctions allow the passage of ions and small molecules (amino acids, sugars, and signaling molecules)

Larger substances like RNA, proteins, or polysaccharides cannot pass

Page 32

5.5 Intercellular Channels Plasmodesmata Are Channels Connecting the Cytoplasm of Adjacent Plant Cells

Compared to gap junctions, plasmodesmata are similar in function but different in structure

The plasma membrane of one cell is continuous with the plasma membrane of an adjacent cell, forming a pore that permits diffusion of small molecules between cells

A desmotubule connects the smooth ER membranes of adjacent cells

The size of the opening can vary for plasmodesmata (closed, open, and dilated states)

Page 33

5.6 Exocytosis and Endocytosis Section 5.6 Learning Outcomes

1) Describe the steps in exocytosis and endocytosis

2) Compare and contrast 3 types of endocytosis

3) Identify the processes of exocytosis, receptor- mediated endocytosis, pinocytosis, and phagocytosis in a figure

Page 34

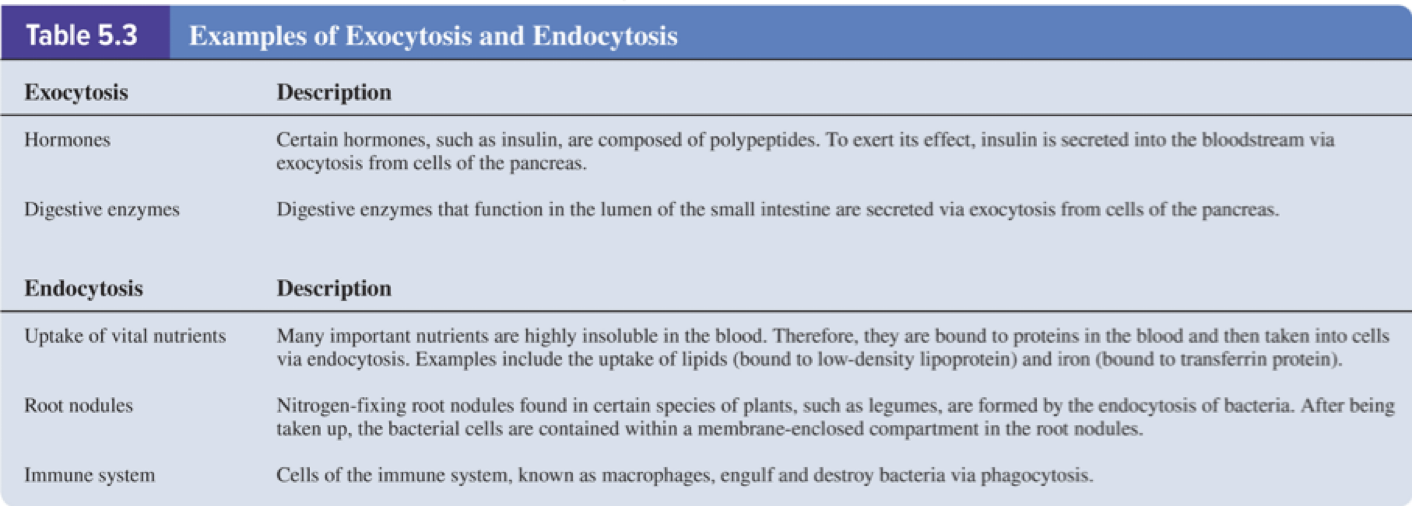

5.6 Exocytosis and Endocytosis

Endocytosis and exocytosis are mechanisms of vesicular transport that move large material into or out of cells

Page 35

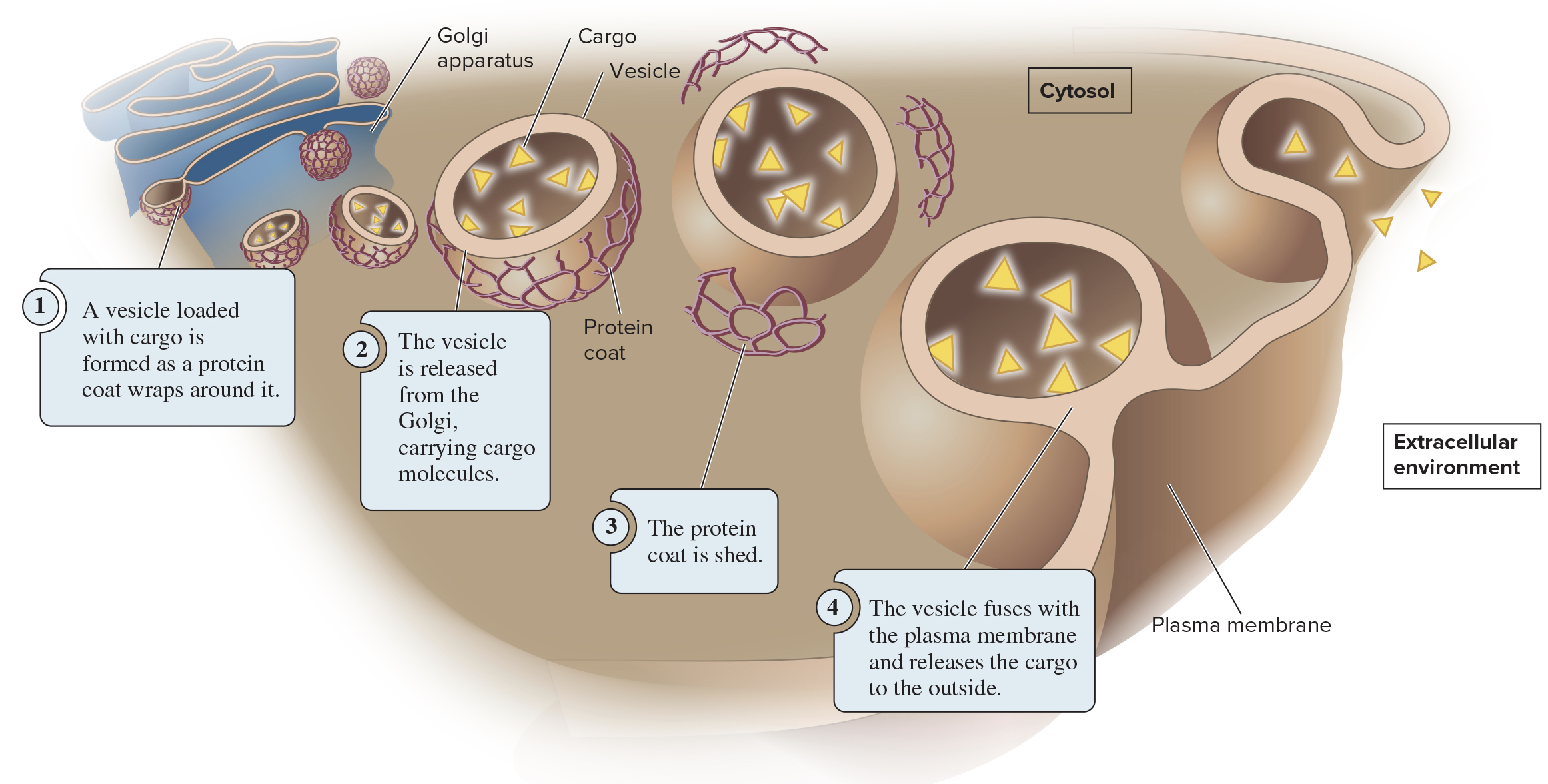

5.6 Exocytosis and Endocytosis

During exocytosis, materials inside the cell are packaged into vesicles and excreted to the extracellular environment

These vesicles are usually derived from the Golgi

Page 36

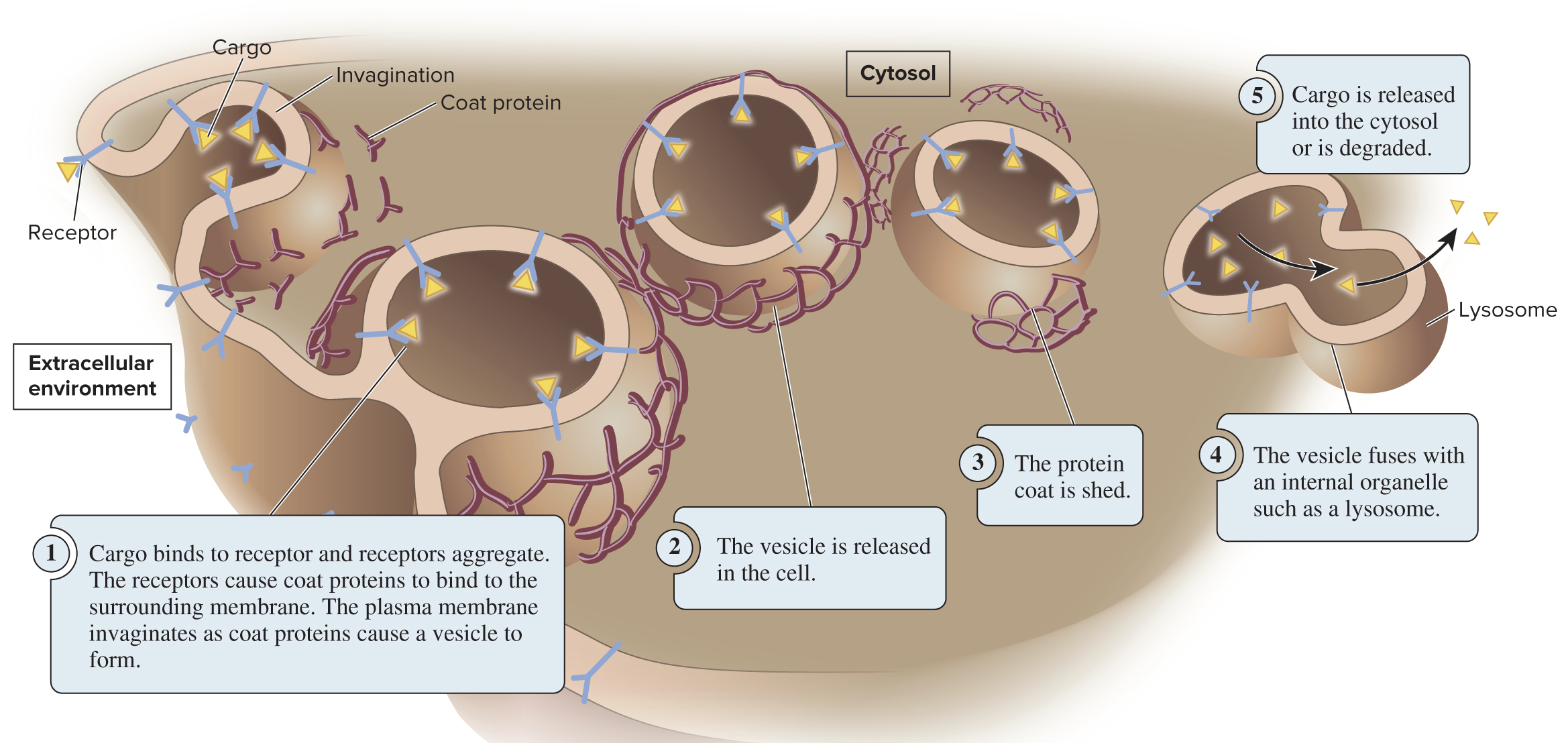

5.6 Exocytosis and Endocytosis

During endocytosis, the plasma membrane invaginates (folds inward) to form a vesicle that brings substances into the cell

Three types of endocytosis:

Receptor-mediated endocytosis (depicted below) uses receptor proteins to bring in specific cargo

Pinocytosis primarily brings in fluid, allowing cells to sample the extracellular environment

Phagocytosis involves bringing in very large particles (ex: a bacterial cell); only some cells are phagocytes

Page 37

5.7 Cell Junctions Section 5.7 Learning Outcomes

1) Outline the structure and function of anchoring junctions and tight junctions

Page 38

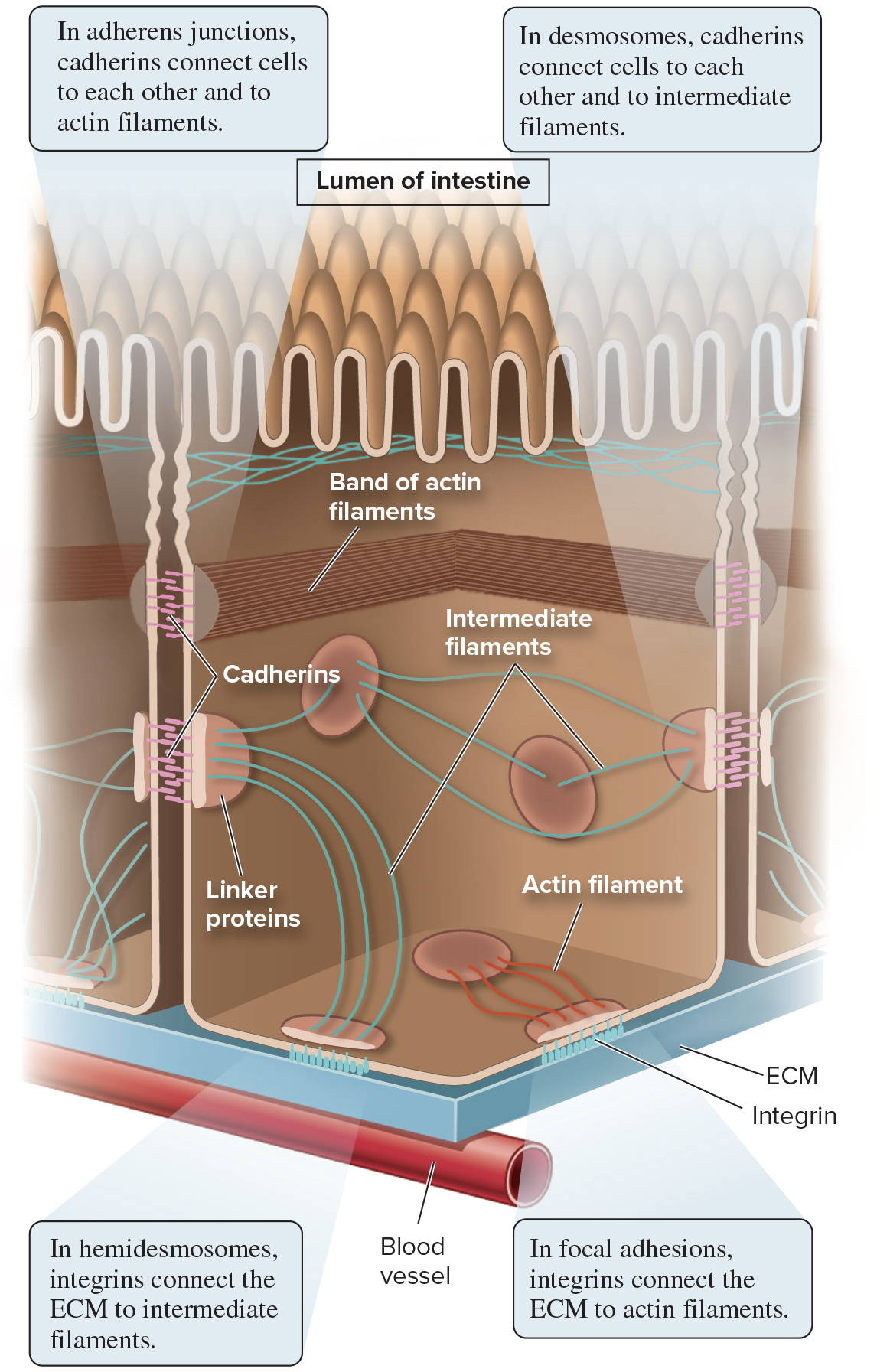

5.7 Cell Junctions Anchoring Junctions Link Animal Cells to Each Other and to the Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

Animals are multicellular; to become multicellular, cells must be linked together

Gap junctions (and plasmodesmata) allow movement of solutes and signals between cells; other junctions physically adhere cells to each other and to the ECM

Anchoring junctions link cells to each other and to the ECM

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are integral membrane proteins that participate in forming these junctions

Cadherins and integrins are 2 types of CAMs

Anchoring junctions are grouped into 4 main categories: adherens junctions, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and focal adhesions

Page 39

5.7 Cell Junctions Anchoring Junctions Link Animal Cells to Each Other and to the Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

Types of anchoring junctions:

Adherens junctions connect cells to each other, use cadherins, and bind actin filaments

Desmosomes connect cells to each other, use cadherins, and bind intermediate filaments

Hemidesmosomes connect cells to the ECM, use integrins, and bind intermediate filaments

Focal adhesions connect cells to the ECM, use integrins, and bind actin

Page 40

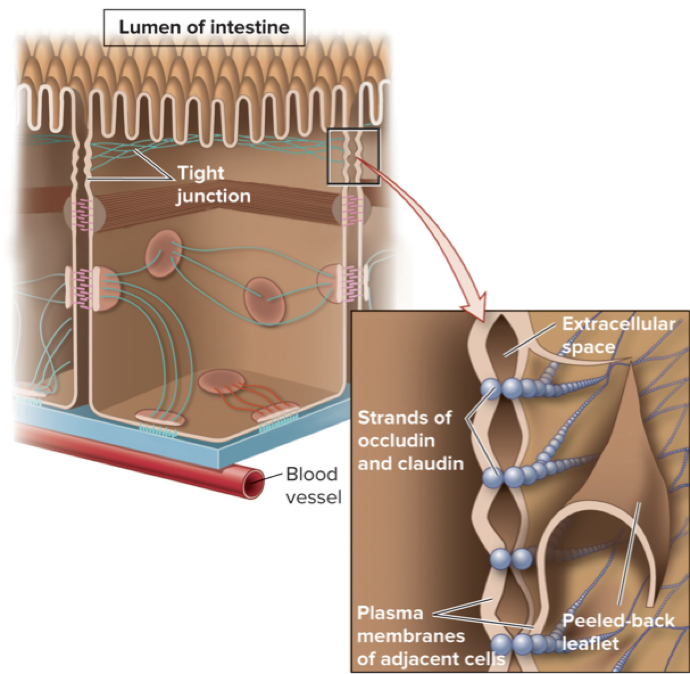

5.7 Cell Junctions Tight Junctions Prevent the Leakage of Materials Across Animal Cell Layers

Tight junctions form a tight seal between cells and prevent material from leaking between adjacent cells

Occludin and claudin are integral membrane proteins used to form tight junctions

Along intestinal lumen, tight junctions:

Prevent leakage of lumen contents into the blood

Help organize different protein transporters on the apical and basal surfaces

Prevent microbes from entering the body

Page 41

Chapter 5 Summary

5.1 Membrane structure

Biological membranes are a mosaic of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates

Proteins associate with membranes in three ways (transmembrane, lipid-anchored, and peripheral)

5.2 Fluidity of membranes

Membranes are semifluid

Lipid composition affects membrane fluidity

Many transmembrane proteins can rotate and move laterally, but some are restricted in their movement

5.3 Overview of membrane transport

The phospholipid bilayer is a barrier to the simple diffusion of hydrophilic solutes

Cells maintain gradients across their membranes

Osmosis is the movement of water across a membrane to balance solute concentrations

Page 42

Chapter 5 Summary (continued)

5.4 Proteins that carry out membrane transport

Channels provide open passageways for solute movement

Transporters bind their solutes and undergo conformational changes

Active transport is the movement of solutes against a gradient

ATP-driven ion pumps generate ion electrochemical gradients

5.5 Intercellular channels

Gap junctions between animal cells provide passageways for intercellular transport

Plasmodesmata are channels connecting the cytoplasm of adjacent plant cells

5.6 Exocytosis and endocytosis

Vesicles are used to transport large molecules and particles during endocytosis and exocytosis

Page 43

Chapter 5 Summary (closing)

5.7 Cell junctions

Anchoring junctions (adherens junctions, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and focal adhesions) link animal cells to each other and to the extracellular matrix

Tight junctions prevent the leakage of materials across animal cell layers

Key conceptual connections and implications

The membrane is a dynamic, heterogeneous, selectively permeable barrier essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis

Transport proteins enable selective movement of ions and molecules, shaping gradients that power many cellular processes

Intercellular channels and junctions coordinate tissue-level function, communication, and structural integrity

Equations and numerical references to remember:

Na+/K+-ATPase stoichiometry: 3\,\mathrm{Na^+}{out} \text{ exported} \; \text{for} \; 2\,\mathrm{K^+}{in} \; \text{imported} \text{ per ATP hydrolysis}.

Secondary active transport concept: the energy of a pre-existing ion gradient drives import of another solute, e.g., \Delta G{gradient} + \Delta G{transport} < 0 for coupled transport (illustrated by H^+ gradient driving sucrose uptake via an H^+/sucrose symporter).

Practical applications and real-world relevance

Ion pumps account for a large portion of cellular energy expenditure (up to ~70%) and are central to processes like nerve signaling and muscle contraction

Electrochemical gradients power nutrient uptake, neurotransmitter reuptake, and secondary transport in various organisms

Tight junctions and adherent junctions contribute to organ function (intestine sealing, barrier formation) and tissue integrity

Ethical/philosophical/practical implications

Understanding membrane transport helps explain pharmacokinetics and drug design (how drugs cross membranes or are expelled by pumps)

Dysfunction in membranes or transport proteins can lead to diseases (e.g., ion pump defects, impaired gap junction communication)