Syllabus Summary

Students investigate:

Survey

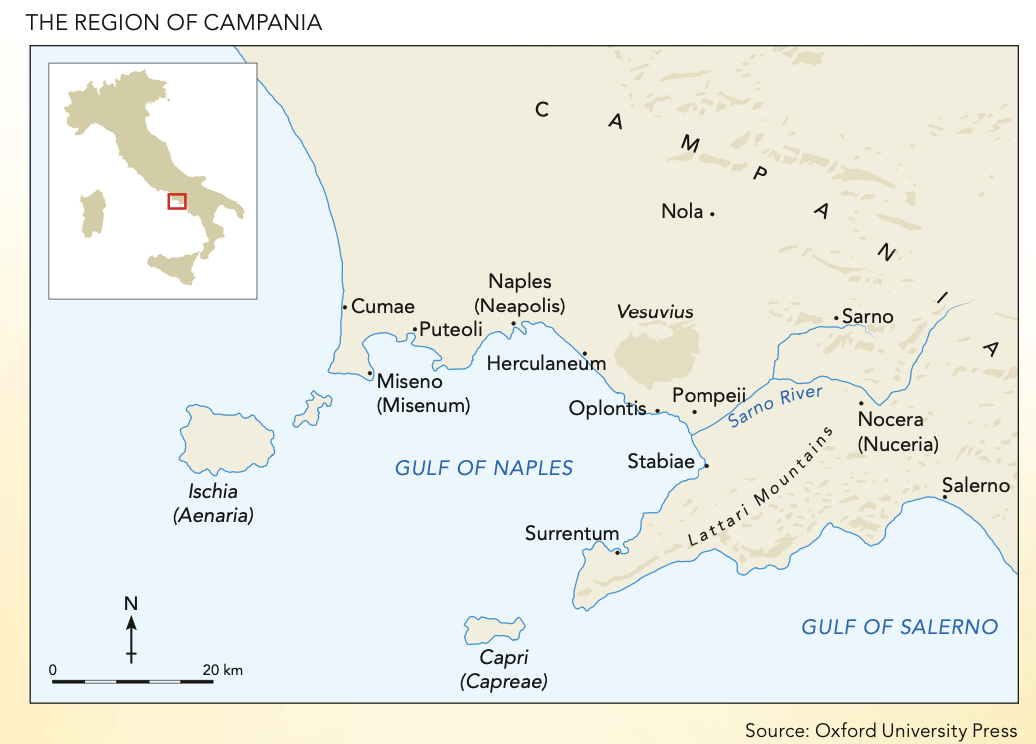

● The geographical setting and natural features of Campania

Pompeii was built on a volcanic plateau covering an are of over 66 hectares. This plateau was located between the Sarno River in the south and the fertile slopes of Mount of Vesuvius to the north. Pompeii was strategically important because it lay on the only route linking north and south, and connected the seaside area with the fertile agricultural region of the inland.

● The eruption of AD 79 and its impact on Pompeii and Herculaneum

Mount Vesuvius had not erupted in living memory, so when the top of the mountain exploded on 24 August AD 79, no one realised that it was the beginning of a disaster of catastrophic proportions. The statistics are sobering:

- A cloud of volcanic gas, ash and stones rose to heights of up to 30km

- Molten rock and pumice ejected at a rate of 1.5 million tonnes per second

- The thermal energy released was 100 000 times greater than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima

- Possibly thousands of people died

- The settlements of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae were completely buried

The people of Pompeii and Herculaneum apparently did not connect earthquakes and tremors with volcanic activity from Vesuvius. On 5 February AD 62, a violent earthquake severely damaged both cities. A subsequent earthquake was recorded in AD 64 by the Roman writers Suetonius and Tacitus. Another warning sign was that the water supply had been interrupted in Pompeii by seismic activity.

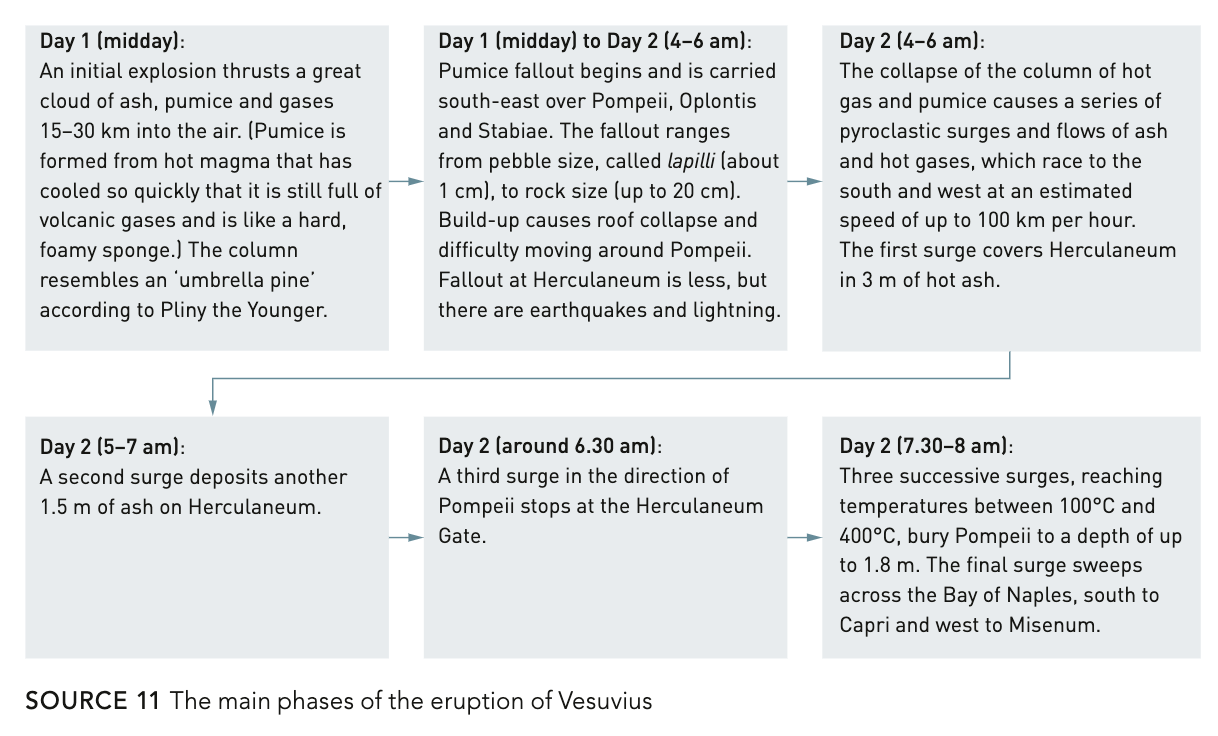

Phases in the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79

Vulcanologists have made a close study of Mount Vesuvius, including detailed stratigraphic analysis, and have established the main phases of the eruption as it occurred in AD 79.

The destruction of Herculaneum

Herculaneum lay directly under Mount Vesuvius, only 7km from its peak, and was situated between two streams that flowed down the slopes of the mountain. It suffered a different, more horrific, fate than Pompeii. Because Herculaneum was upwind of the fallout, the pumice fall in the first few hours was moderately light. However, in the next and most destructive phase of the eruption, Herculaneum bore the full brunt of the succession of pyroclastic surges. The first surge, arriving no more than 5 minutes after the collapse of the eruption column, dumped 3 metres of hot ash on the town. The following five surges and flows destroyed buildings and carbonised timber and other organic matter. In the final phase, the city was buried up to 23 metres deep and the coastline was extended by about 400 metres.

What happened at Pompeii?

The distance that Pompeii had from Mount Vesuvius meant they escaped the first two surges. The fourth surge, reaching temperatures of up to 400°C, which may have accompanied by toxic gases, penetrated the whole town. Two more surges destroyed most of the structures that were still above the pumice layer. The amount of ash deposited varied from about 1.8 metres in the north, to about 60 centimetres in the south.

Date of eruption contested

The traditional date of the eruption is 24 August AD 79. This is based on an 11th-century summary of the work of Cassius Dio, a Roman writer in the 3rd century AD. Recently, debate has arised as some scholars have been favouring autumn for the eruption rather than the summer of that year.

Arguments in favour of a summer date include:

the discovery of the leaves of deciduous trees

evidence of summer-flowering herbs found at Villa A at Oplontis

evidence of summer-ripening broad beans found at the House of the Chaste Lovers at Pompeii

the fact that the last batch of garum from Pompeii was made with a type of fish that was plentiful in July (i.e. summer)

Arguments in favour of an autumn date include:

discovery of late autumn-ripening fruits such as pomegranates

Epigraphic evidence points to this happening no earlier than September of that year. According to this evidence, the eruption of Vesuvius is most likely to have taken place in the autumn of AD 79, that is, later the same year.

How did people die at Pompeii and Herculaneum?

People died from thermal shock (a large and rapid change in temperature that can have dangerous effects on living organisms) and fulminant shock (a cause of death associated with intense heat).

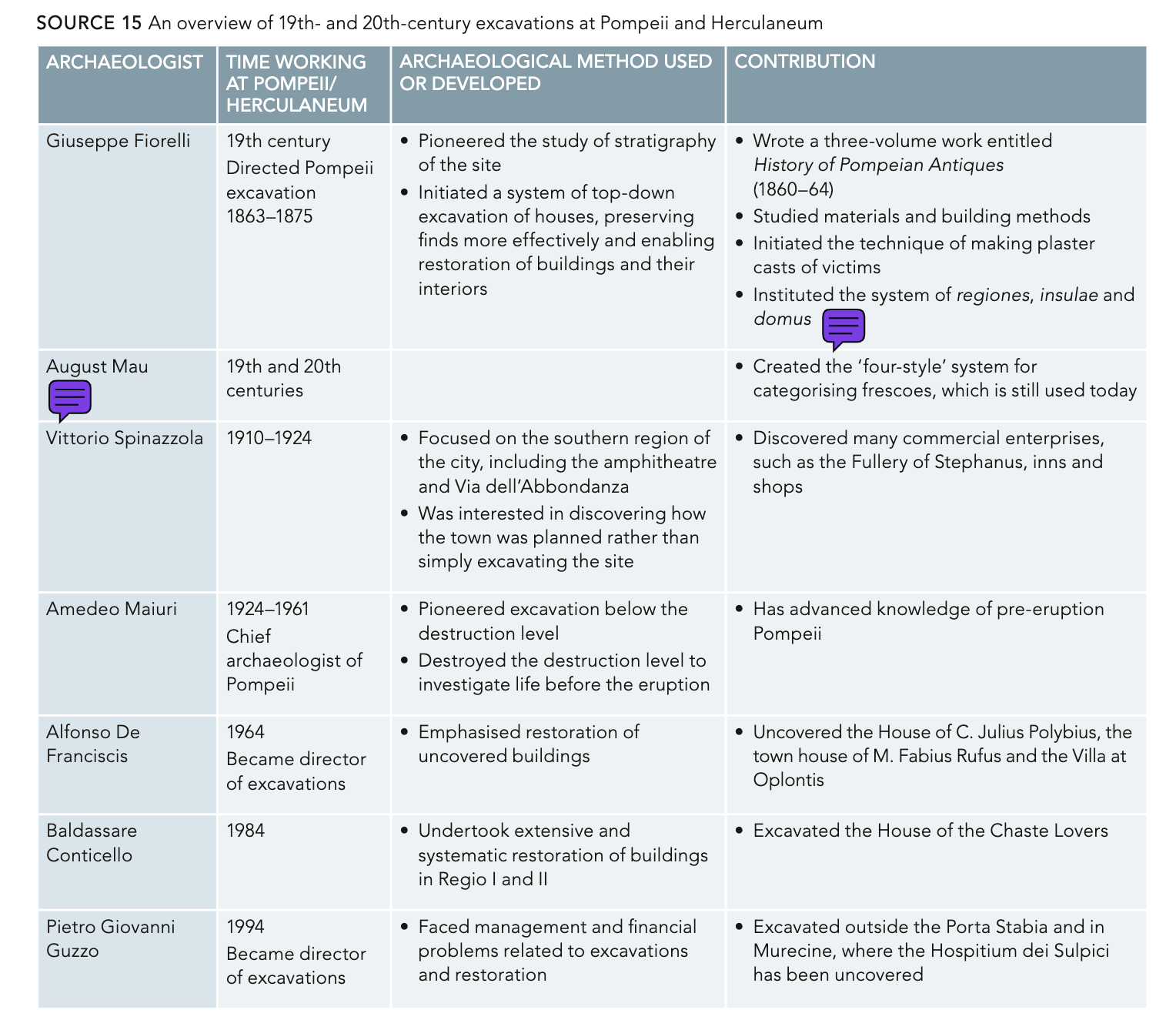

● Early discoveries and the changing nature of excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries

● Representations of Pompeii and Herculaneum over time

Pliny the Younger’s written account is the first known representation that provides us with our most detailed primary evidence:

From 18th century onwards, European artists have produced engravings and paintings that portray elements of his account.

eg. Karl Briullov’s 1830 masterpiece, The Last Days of Pompeii, which was famous in its day, depicting the terrified inhabitants cowering beneath a sky filled with fire and smoke, or trying to rescue those crushed by falling masonry. Painting can now be seen in the Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Pompeii has been depicted many times in television and film productions.

eg. The 2014 film Pompeii, directed by Paul W.S. Anderson

Focus of Study

Investigating and interpreting the sources for Pompeii and Herculaneum

● the evidence provided by the range of sources, including site layout, streetscapes, public and private buildings, ancient writers, official inscriptions, graffiti, wall paintings, statues, mosaics, human, animal and plant remains from Pompeii and Herculaneum, as relevant for:

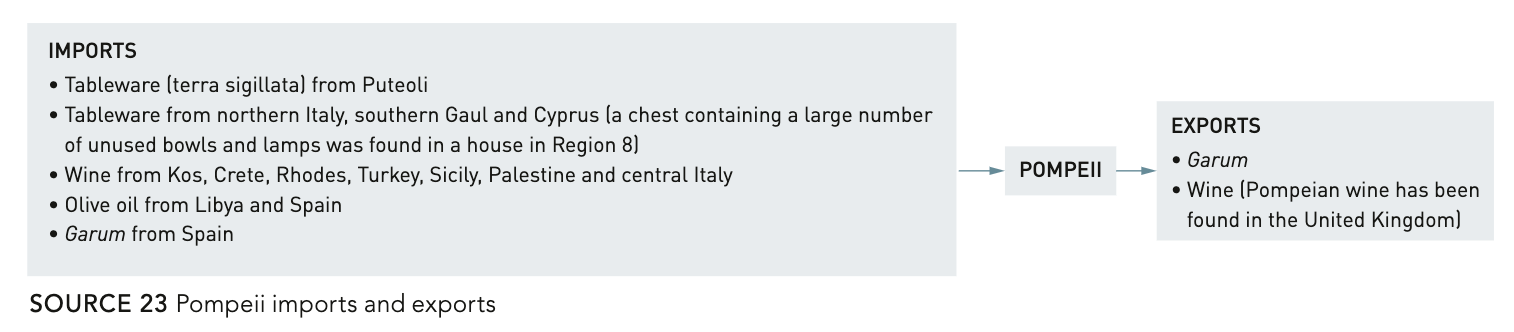

– the economy: role of the forum, trade, commerce, industries, occupations

Role of the forum:

Centre of public life in Pompeii, the town centre.

Trade:

Commerce:

Shops: Numerous shops were located in the front rooms of houses along main roads. Limited material remains complicate the identification of goods sold.

Identifiable shops include:

Mason’s Shop: Identified by a wall painting of masons’ tools; owner was Diogenes.

Carpenter’s Shop: Identified by a wall painting of carpenters’ tools.

Bronze Manufacturing Shop: Excavated in 2016; featured a staircase and furnace, suggesting it produced bronze objects. Four skeletons were found here, indicating people were trapped during the eruption.

Markets: Played a vital role in commerce, with specific markets like the macellum and holitorium mentioned. Not all markets had permanent locations; temporary stalls were set up by vendors selling:

Shoes, cloth, metal vessels, fruits, and vegetables, often near the Forum or amphitheatre for refreshments.

Bars and Inns: Numerous thermopolia (bars) were located on main roads and gates. Dolia (large terracotta pots) in counters likely stored dried food (nuts, grains, dried fruits, vegetables) rather than food and drink, as previously thought. Notable establishments include:

Asellina's Bar: Nearly complete thermopolium.

Inns: Found near Nuceria Gate and Forum, consisting of courtyards and upper-floor rooms, though many remain unidentified due to lack of evidence.

Industries:

Industry played an important role in the economics of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Agriculture, wine and olive oil production were predominant. Another industry at Pompeii was cloth manufacture. Urine as a source of ammonia was used as a part of the process and the fullers left large jars outside their establishments where people could make deposits that were then used in the bleaching process (e.g. the Fullery of Stephanus). Tanners, goldsmiths and silversmiths and dye-makers also used urine in their work.

Occupations:

Pompeii had a large community of artisans that included artists, metalworkers, potters and glassblowers. There were tradesmen, wealthy merchants, manufacturers and service industries employing bakers, innkeepers, bath attendants and brothel keepers. Artwork o depicted putti, or cupids, engages in the various crafts and occupations of the townspeople. In some Pompeian houses, the peristyle operated as a manufacturing workshop. For example, in the house of M. Terentius Eudoxus, there was a weaving workshop, run by male and female slaves.

– the social structure: men, women, freedmen, slaves (in order)

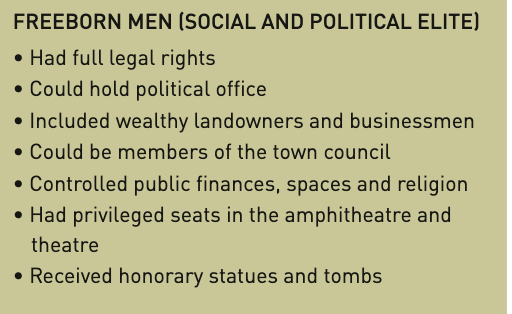

Freeborn Men (men who were born not as slaves):

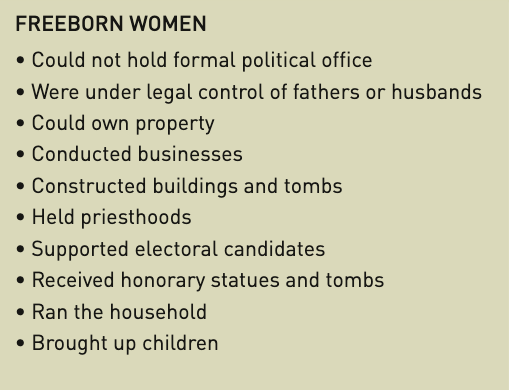

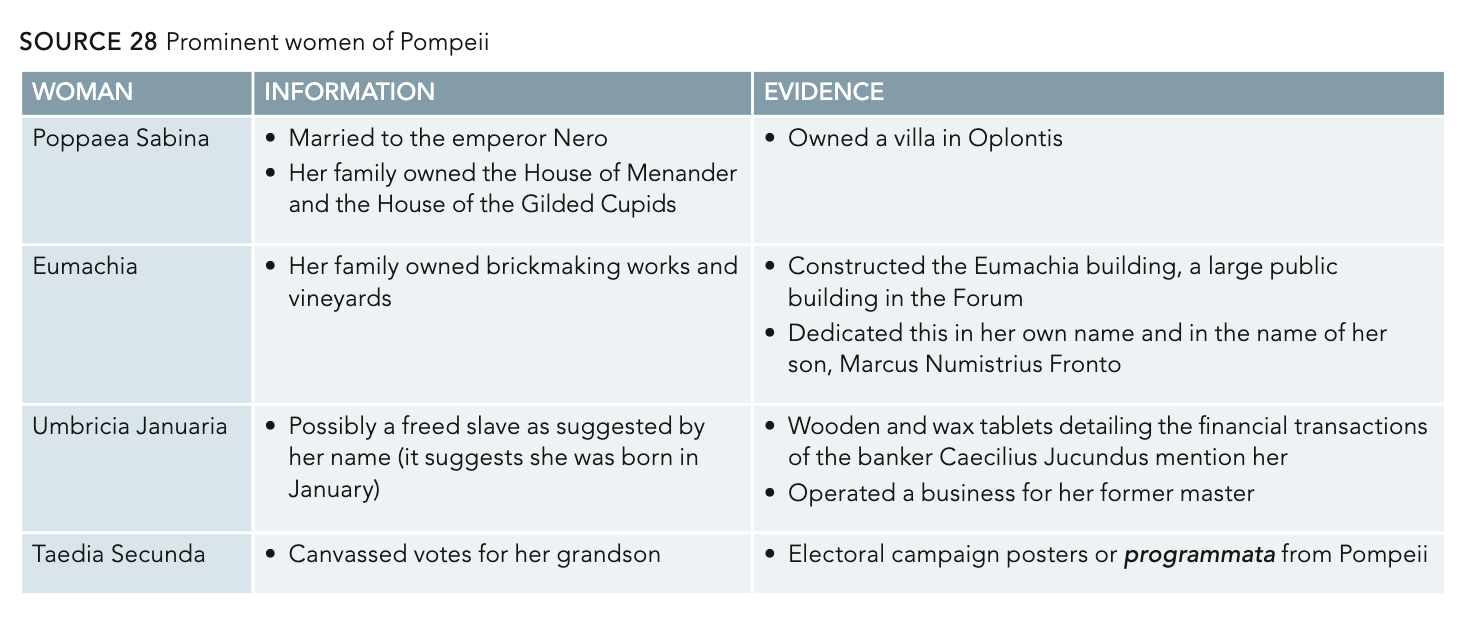

Freeborn Women (women who were born not as slaves):

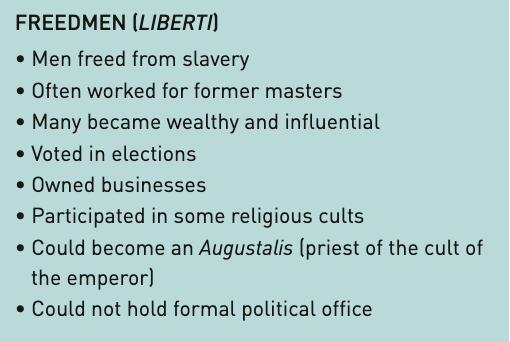

Freedmen (men who were once slaves but were freed):

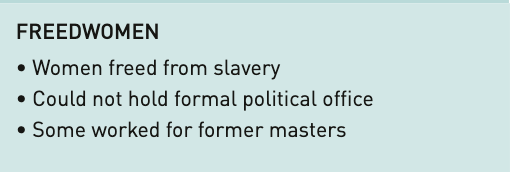

Freedwomen (women who were once slaves but were freed):

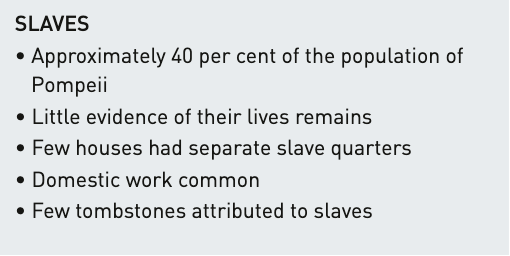

Slaves:

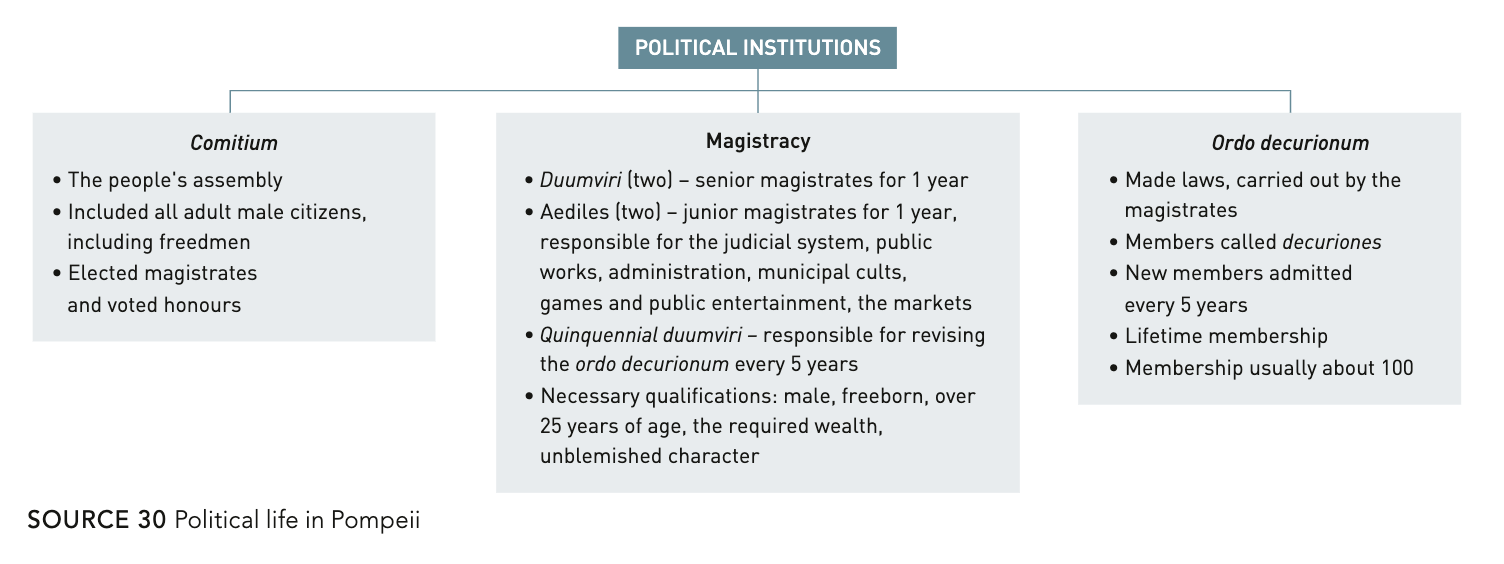

– local political life: decuriones, magistrates, comitium

– everyday life: housing, food and dining, clothing, health, baths, water supply, sanitation, leisure activities

Housing:

Four main styles of housing have been identified in Pompeii and Herculaneum;

the domus or atrium house (e.g. House of Menander)

usually single-storeyed

the atrium-peristyle house (e.g. House of the Vettii)

centrepiece of wealthy homes, gave access to the dining rooms and living rooms

insulae or apartment/lodging houses (e.g. House of the Trellis)

consisted of multi-storeyed apartments or tenements

villas (e.g. Villa of the Mysteries)

large, luxurious, multi-roomed dwellings located on the outskirts of Pompeii and Herculaneum owned by the wealthy citizens of Rome

Food and Dining:

Clothing

Most evidence of clothing in Pompeii and Herculaneum comes from artistic representations; archaeological evidence is minimal.

High-ranking individuals, such as Marcus Nonius Balbus, are depicted wearing togas, though they were not worn all the time due to their heaviness and difficulty in wearing.

The toga was primarily a formal garment, seen in frescoes during religious processions.

Men of rank and the equestrian class commonly wore knee-length, belted tunics, with the width of purple stripes indicating rank.

Working men and slaves wore similar tunics made of coarser, darker wool, often pulled higher over their belts for ease of movement.

Women of rank wore stolas, long, sleeveless tunics worn on top of another tunic, symbolising marriage and respect for tradition.

The stola was accentuated by the palla, a cloak worn over the head when outdoors.

Health:

Main evidence for the health of residents of Pompeii and Herculaneum comes from human remains studied by Dr. Estelle Lazer from Sydney University.

Examination includes around 300 skulls, indicating people were generally well nourished.

Average height: 167 cm for men and 155 cm for women.

Tooth wear and decay likely caused by particles from basalt grindstones used in flour production.

Evidence of hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI), a thickening of the frontal bone normally seen in post-menopausal women, affecting about 12% of the female population.

Common diseases include tuberculosis and malaria, with higher death rates in wealthier areas due to mosquito breeding grounds in garden water features.

Investigation of remains from a group attempting to escape the eruption revealed that 1 in 5 were infected with brucellosis (Malta fever), linked to contaminated milk products.

Surgical instruments found in Pompeii, indicating medical practices, but remains suggest fractures often healed without reset.

Baths:

Pompeii

Four main public baths: Forum Baths, the Stabian Baths, the Central Baths and the Amphitheatre Baths.

Stabian Baths: oldest and largest baths in Pompeii from as early as the 4th century BC (had earliest known hypocaust —> installed in 1st century BC). Excavations began in the 1850s, revealing that looters had raided these baths in the years following the AD 79 eruption.

At the time baths were decorated with fine Fourth-Style frescoes, multicoloured stucco bas reliefs, mosaic floors and marble fittings. The earthquake of AD 62 severely damages these baths and some areas were not in use at the time of the eruption.

Herculaneum

Two bathing complexes: Forum Baths and the Suburban Baths.

Forum Baths: built between 30 and 10 BC and follow the standard Roman design of baths.

Suburban Baths: located outside the town walls, near the sea. It is in a very good state of preservation, but difficult to excavate due to the dense volcanic rock and the lowered table. Damage has been done not only by eruption, but also by tunnellers in the early days of excavation.

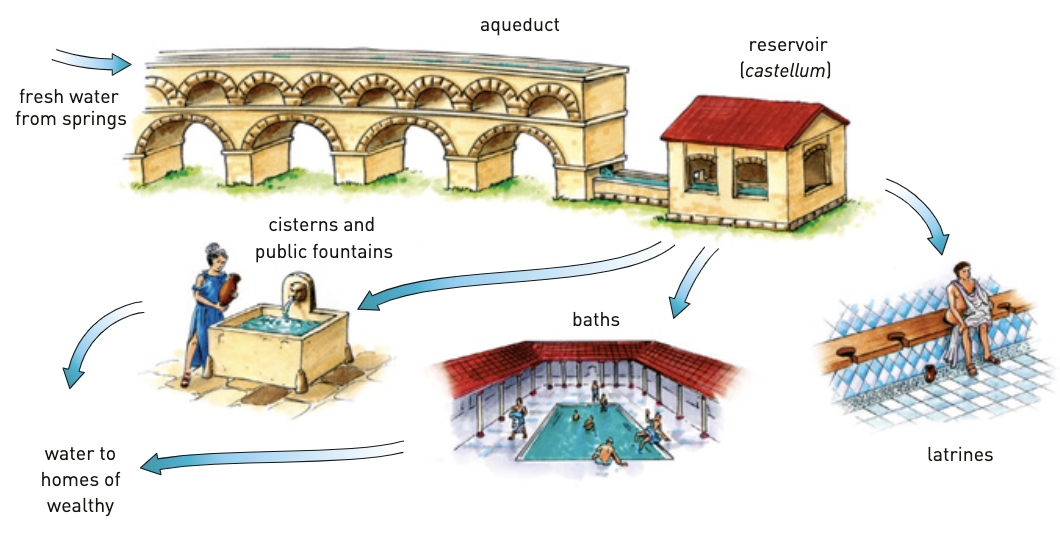

Water Supply:

At the time of Augustus, the imperial aqueduct at Misenum had a branch built to supply Pompeii (Serinum aqueduct). Water from this channel flowed into a main tank or water tower (castellum aquae) near the Vesuvian Gate. From the castellum, it was siphoned off into three main pipes that fed different areas of the city. The sloping terrain aided the water pressure that dispersed the water to various tanks all over Pompeii. Fourteen of these secondary tanks have been uncovered. Many private homes in Pompeii were connected directly to this source of fresh, running water.

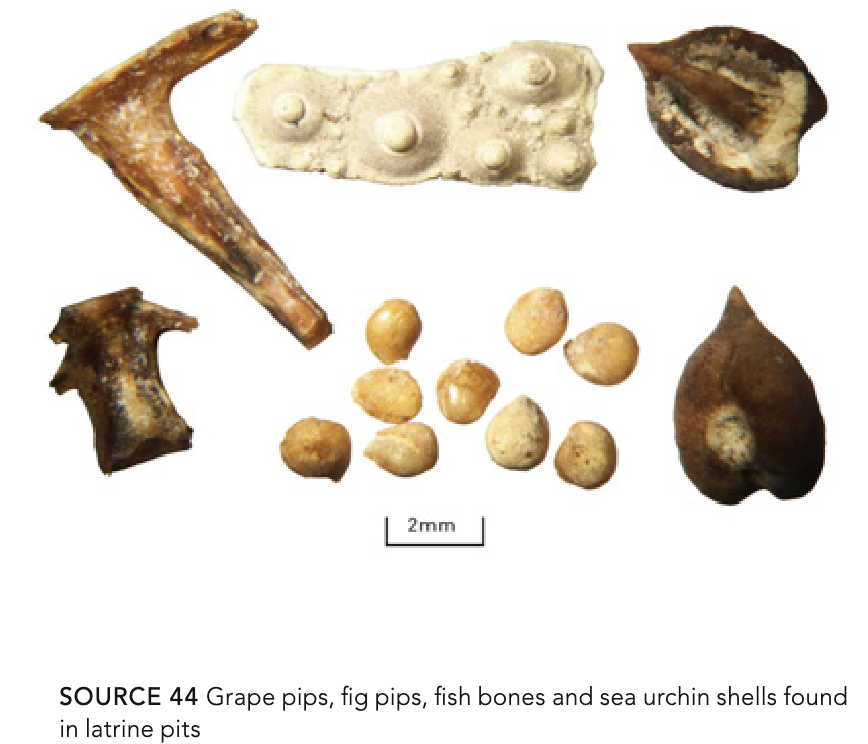

Sanitation:

Pompeii was noisy, dirty, smelly and generally unhygienic, with rubbish in the streets. Like most Roman towns, it had public latrines.

Seating for 20 people has been found in the north-west corner of the Forum at Pompeii. There was no toilet paper, only a sponge on a stick. Latrines were also located at the baths and the palaestra.

Some private homes in Pompeii and Herculaneum, such as the House of the Painted Capitals, had latrines. These were often near the kitchen area and were flushed by hand or connected to the house’s water supply from the aqueduct. The wast was drained away to cesspits underneath the roadway or to the sewerage system.

Private toilets were usually only for one or two people; however houses in Herculaneum catered for up to 6 users.

Leisure Activities:

Theatres:

Pompeii had two theatres: the Large Theatre and the smaller Odeion.

The Large Theatre: constructed on the Greek model with semicircular, tiered seating that had a capacity of up to 5000. Building dates to the 2nd century BC, with additions made during the reign of Augustus by Marcus Holconius Rufus, a local official.

The Odeion: a covered structure of smaller capacity. The seating was arranged and decorated according to social status. Because it was roofed, the acoustics were good and well suited for the poetry readings and concerts that were held there (same as Large Theatre).

Herculaneum: the theatre was a freestanding structure of 19 rows of tiered seating with a seating capacity of about 2000. The well-known local identity Marcus Nonius Balbus is commemorated in inscriptions and statues along with statues of gods and imperial and local figures.

Several different types of entertainment, including plays, farces and pantomimes, were held at the theatres at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The palaestra:

Gladiatorial Games:

The Amphitheatre:

Other leisure activities:

– religion: household gods, temples, foreign cults and religions, tombs

1.9 + 1.12 + 1.13

– the influence of Greek and Egyptian cultures: art and architecture

1.14

Reconstructing and conserving the past

● changing interpretations: impact of new research and technologies

1.15

● issues of conservation and reconstruction: Italian and international contributions and responsibilities

1.16

● ethical issues: excavation and conservation, study and display of human remains

1.17

● value and impact of tourism: problems and solutions

1.18