Chapter 9: Islamic Art

Key Notes

- Time Period: 630 C.E. to the Present

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Islamic art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

- In the Islamic period, scientific and mathematical experimentation was prioritized.

- Islamic art incorporates text.

- Islamic artists created ceramics and metalwork that are particularly well-regarded.

- Islamic textiles include silk and wool used for tapestries and carpets.

- Islamic manuscripts are written on paper, cloth, or vellum.

- Islamic art favors a two-dimensional approach to painting, emphasizing geometric designs and organic forms.

- Cultural interactios

- There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

- There is a great influence of Roman, Early Medieval, and Byzantine art on Islamic art.

- Islamic art has a strong calligraphic tradition.

- Even though Islamic art is produced over a wide geographic area, it has a number of shared similarities and characteristics.

- There is a strong pilgrimage tradition in Islam.

- Audience, functions and patron

- Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

- Architecture is mostly religious.

- Often great works of Islamic art were created for royal and wealthy patrons.

- Theories and Interpretations

- The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

- Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

- Islamic art created for religious purposes is not figural.

- Mosque architecture contains no figural imagery, but it does have geometric, calligraphic, and organic decoration.

- In a secular context, Islamic art is sometimes figural especially in manuscript painting.

Historical Background

- The Prophet Muhammad’s powerful religious message resonated deeply with Arabs in the seventh century, and so by the end of the Umayyad Dynasty in 750 C.E., North Africa, the Middle East and parts of Spain, India, and Central Asia were converted to Islam or were under the control of Islamic dynasties.

- Muhammad (570?–632): The Prophet whose revelations and teachings form the foundation of Islam

- The Islamic world expanded under the Abbasid Caliphate, which ruled a vast empire from their capital in Baghdad.

- After the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258, the Islamic world split into two great cultural divisions:

- the East, consisting of South and Central Asia, Iran, and Turkey; and

- the West, which included the Near East and the Arabic peninsula, North Africa, parts of Sicily and Spain.

- Islam exists in two principal divisions, Shiite and Sunni, each based on a differing claim of leadership after Muhammad’s death.

- Qur’an: the Islamic sacred text, dictated to the Prophet Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel

Patronage and Artistic Life

- One of the most popular art forms in the Islamic world is calligraphy, which is based upon the Arabic script and varies in form depending on the period and region of its production.

- It is considered to be the highest art form in the Islamic world as it is used to transmit the texts revealed from God to Muhammad.

- Calligraphy: decorative or beautiful handwriting

- Calligraphers therefore were the most respected Islamic artists.

- By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, writing examples are signed or attributed to specific calligraphers.

- Even royalty dabbled in calligraphy, raising the art form to new heights.

- Apprenticeships were exacting, making students master everything including the manufacture of ink and the correct posture for sitting while writing.

Islamic Painting and Sculpture

- Islamic art features three types of patterns—arabesques, calligraphy, and tessellation— used on everything from great monuments to simple earthenware plates; sometimes all three are used on the same item.

- Arabesque: a flowing, intricate, and symmetrical pattern deriving from floral motifs

- Favorite arabesque motifs include acanthus and split leaves, scrolling vines, spirals, wheels, and zigzags.

- Calligraphy is highly specialized, and comes in a number of recognized scripts, including Kufic.

- The Arabic alphabet has 28 letters from 17 different shapes, and is written from right to left.

- Arabic numerals, however, are written left to right as they are in the West.

- Kufic: a highly ornamental Islamic script

- Kufic is highly distinguished, and has been reserved for official texts, indeed has been the traditional, but not the only, script for the Qur’an.

- Tessellations, or the repetition of geometric designs, demonstrate the Islamic belief that there is unity in multiplicity.

- Tessellation: decoration using polygonal shapes with no gaps

- Their use can be found on objects as disparate as open metalwork and stone decorations.

- Perforated ornamental stone screens, called jali, were a particular Islamic specialty.

- Jali: perforated ornamental stone screens in Islamic art

- All of these designs, no matter how complicated, were achieved with only a straightedge and a compass.

- Islamic mathematicians were thinkers of the highest order; geometric elements reinforced their idea that the universe is based on logic and a clear design.

- Patterns seem to radiate from a central point, although any point can be thought of as the start.

- These patterns are not designed to fit a frame, rather to repeat until they reach the edge, and then by inference go beyond that.

- Islamic textiles, carpets in particular, are especially treasured.

- Mosques have elaborate prayer rugs with the mihrab motif to provide a clean and comfortable place to kneel.

- Royal carpets typically had hundreds of knots per square inch. In tribal villages, women knotted or flat-weaved smaller carpets.

➼ Pyxis of al-Mughir

Details

- From Umayyad

- 968, ivory

- Found in Louvre, Paris

- Pyxis: a small cylinder-shaped container with a detachable lid used to contain cosmetics or jewelry

Form

- Horror vacui.

- Vegetal and geometric motifs. Material

- Intricately carved container made from elephant ivory.

Function

- Container for expensive aromatics, sometimes also used to hold jewels, gems, or seals.

- Gift for the caliph’s younger son.

Content: Four polylobed medallion scenes showing pleasure activities of the royal court: hunting, falconry, sports, music.

Context

- Calligraphic inscription in Arabic names the owner, asks for Allah’s blessings, and includes the date of the pyxis.

- From Muslim Spain.

Image

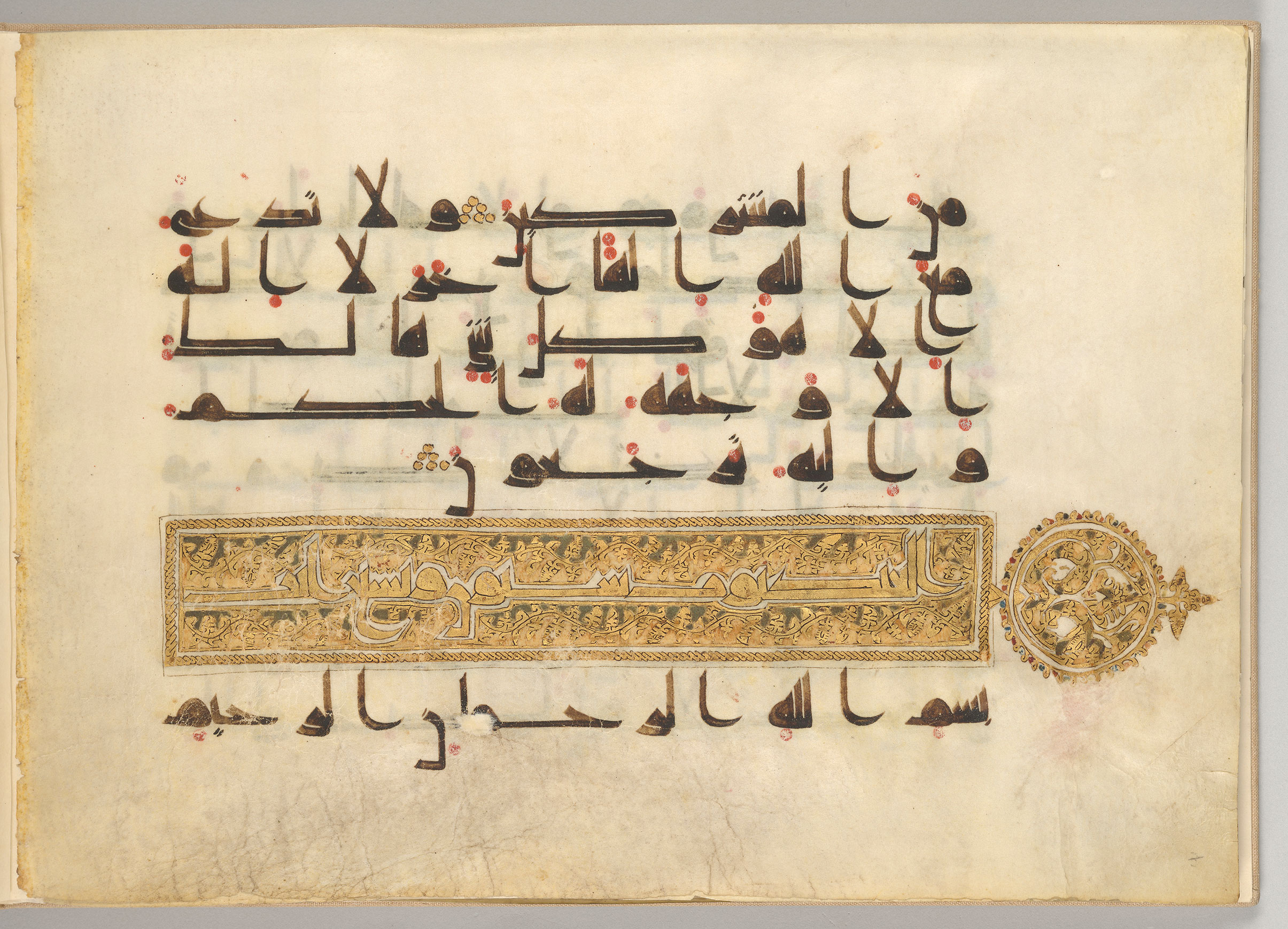

➼ Folio from a Qur’an, Arab

Details

- North Africa or Near East, Abbasid

- 8th–9th century

- Made of ink, color, and gold on parchment

- Found in Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Form

- The title of each chapter is scripted in gold.

- Script is rigidly aligned in strong horizontal letters well-spaced apart in brown ink.

- Kufic script; strong uprights and long horizontals.

- Great clarity of text is important because several readers read a book at once, some at a distance.

- Arabic reads right to left.

- Consonants are scripted, vowels are indicated by dots or markings around the other letters.

- The diacritical markings of short diagonal lines and red dots indicate vocalizations.

- Pyramids of six gold discs mark the ends of ayat (verses).

Function: The Qur’an is the Muslim holy book.

Context

- Qur’ans were compiled and codified in the mid-seventh century; however, the earliest surviving Qur’an is from the ninth century.

- Calligraphy is greatly prized in Qur’anic texts; elaborate divine words needed the best artists.

- Illustrated is the heading of sura 29 (al-’Ankabūt, or “The Spider”) in gold.

- The text indicates that those who believe in protectors other than Allah are like spiders who build flimsy homes.

Image

➼ Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)

Details

- Designed by Muhammad ibn al-Zain

- 1320–1340

- Maid of brass inlaid with gold and silver

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Function

- Original use is for ceremonial hand washing; perhaps a banqueting piece.

- Later use is for baptisms for the French royal family; coats-of-arms originally on the work were reworked with French fleur-de-lys.

Content

- Signed by the artist six times.

- Hunting scenes alternate with battle scenes along the side of the bowl.

- Mamluk hunters and Mongol enemies.

- Bottom of bowl decorated with fish, eels, crabs, frogs, and crocodiles.

Patronage

- There is no patron or date identifying the work, although some scholars feel that the basin is connected to the amir Salar (d. 1310), whose image may be prominently depicted on one of the roundels.

- In that regard, it may have been a gift from Salar to a sultan.

Image

➼ The Ardabil Carpet

Details

- Designed by Maqsud of Kashan

- 1539–1540

- Made of silk and wool

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Function

- Prayer carpet used at a pilgrimage site of a Sufi saint.

- Huge carpet, one of a matching pair, from the funerary mosque of Shayik Safial-Din; probably made when the shrine was enlarged.

- The companion carpet is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Materials

- Wool carpet, woven by ten people, probably men; although women also did weaving in this period.

- The importance of the location and the size of the project indicate that men were entrusted with its execution.

Technique: Wool pile of 5,300 knots per 10 cm. sq.; allows for great detail.

Content

- Medallion in center of carpet may represent the inside of a dome with 16 pendants.

- Mosque lamps hang from two of the pendants; because one lamp is smaller than the other, the larger lamp is placed farther away so that it appears the same size as the smaller; some suggest that this is a deliberate flaw to reflect that God alone is perfect.

- Corner squinches also have pendants completing the feeling of looking into a dome.

- Inscription says, “Except for thy threshold, there is no refuge for me in all the world.

- Except for this door there is no resting-place for my head.

- The work of the slave of the portal, Masqud Kashani,” and the date, 946, in the Muslim calendar.

- The word “slave” in the inscription has been variously interpreted, but generally it is agreed that he was not a slave in the literal sense, but someone who was charged with executing the carpet.

Context: World’s oldest dated carpet.

Image

Persian Manuscripts

- The Mongolian rulers who conquered Iran in 1258 introduced exotic Chinese painting to the Iranian court in the late Middle Ages.

- Persian manuscript paintings (miniatures) gave a visual image to a literary plot, rendering a more enjoyable and easier-to-understand text

- Centuries after the Mongols, Chinese elements remain in figures' Asiatic appearance, Chinese rocks and clouds, and dragons and chrysanthemums. Persian miniatures influenced Mughal manuscripts.

- Many Persian manuscripts depict figures in a shadowless world, usually richly dressed and decorated.

- Persian artists admire intricate details and multicolored geometric patterns.

- Space is divided into a series of flat planes.

- Words are often written with precision in spaces reserved for them on the page, emphasizing the marriage of text and calligraphy.

- The viewer's perspective changes as they look directly at some figures and down at the floor and carpets.

- Artists depict lavishly ornamented architectural settings with crowded compositions of doll-like figures in bright colors.

➼ Bahram Gur Fights the Karg

Details

- Folio from the Great Il-Khanid Shahnama, Islamic; Persian

- c. 1330–1340

- Made of ink and opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper

- Found in Harvard University Art Gallery, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Shahnama, or The Book of Kings: a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Firdawsi between c. 977 and 1010 c.e.; the national epic of Iran

Form

- Large painted surface area; calligraphy on the top and bottom frame the image.

- Areas of flat color.

- Spatial recession indicated by the overlapping planes.

- Atmospheric perspective seen in the light-bluish background.

Content

- Bahram Gur was an ancient Iranian king from the Sassanian dynasty.

- He represents the ideal king; wears a crown and a golden halo.

- Mongol artists of Persia sought to link themselves to great ancient Persian heroes shown as Mongol horsemen.

- A karg is a kind of unicorn or horned wolf he fought during his trip to India.

- Cross-cultural influences are Bahram Gur wears a garment of European fabric; Chinese landscape conventions can be seen in the background; these aspects connect the painting with trade along the Silk Road.

Context

- Its lavish production suggests it was commissioned by a high-ranking Ilkhanid court official and produced at the court scriptorium as a chronicle of great Persian kings.

- A high point of Persian manuscripts; very lavish.

- The original story by Firdawsi was written around 1010.

- Folio from the text called the Great Ilkhanid Shahnama, or the Book of Kings, a Persian epic.

- Originally one of 280 folios by several different artists; 57 pages survive.

Image

➼ The Court of Gayumars

Details

- Created by Sultan Muhammad

- From the Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama

- 1522–1525

- Made of ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

- Found in Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, Canada

Form

- Large painted surface area; calligraphy diminished.

- Harmony between man and landscape.

- Minute details do not overwhelm the harmony of the scene.

- Very richly and decoratively painted with vibrant colors.

- Minute scale suggest the use of fine brushes, perhaps of squirrel hairs.

Content

- This excerpt shows the first king of Iran, Gayumars, enthroned before his community, ruling from a mountaintop.

- During his reign, men learned how to prepare food and prepare leopard skins as clothing; wild animals are shown as meek and submissive.

- On left, his son Siyamak; on right, his grandson Hushang.

- His court appears in a semicircle below him; court attire includes the wearing of leopard skins.

- The angel Surush tells Gayumars that his son will be murdered by the Black Div, son of the demon Ahriman; his death will be avenged by Hushang, who will rescue the Iranian throne.

Context

- Persian manuscript.

- The original story by Firdawsi was written around 1010.

- Folio from the text called the Great Ilkhanid Shahnama or the Book of Kings, a Persian epic.

- Produced for the Safavid ruler of Iran, Shah Tahmasp I, who saw himself as part of a proud tradition of Persian kings.

- Whole book contains 258 illustrated pages.

Image

Islamic Architecture

- The qiblah, or direction, to Mecca is marked by the mihrab an empty niche, which directs the worshipper’s attention.

- Qibla: the direction toward Mecca which Muslims face in prayer

- Mecca, Medina: Islamic holy cities; Mecca is the birthplace of Muhammad and the city all Muslims turn to in prayer; Medina is where Muhammad was first accepted as the Prophet, and where his tomb is located

- To remind the faithful of the times to pray, great minarets are constructed in every corner of the Muslim world, from which the call to prayer is recited to the faithful.

- Minaret: a tall, slender column used to call people to prayer

- Minarets are composed of a base, a tall shaft with an internal staircase, and a gallery from which muezzins call people to prayer. Galleries are often covered with canopies to protect the occupants from the weather.

- Muezzin: an Islamic official who calls people to prayer traditionally from a minaret

- Mosques come in many varieties. The most common designs are either the hypostyle halls like the Great Mosque at Córdoba (eighth–tenth centuries) or the unified open interior as the Mosque of Selim II.

- Hypostyle: a hall that has a roof supported by a dense thicket of columns

- The focus of all prayer is the mihrab, which points the direction to Mecca.

- Mihrab: a central niche in a mosque, which indicates the direction to Mecca

- The Mosque of Selim II has a unified central core with a brilliant dome surmounting a centrally organized ground plan.

- Works like this were inspired by Byzantine architecture.

- The domes of mosques and tombs employ squinches, which in Islamic hands can be made to form an elaborate orchestration of suspended facets called muqarnas.

- Muqarna: a honeycomb-like decoration often applied in Islamic buildings to domes, niches, capitals, or vaults. The surface resembles intricate stalactites

- In Iran mosques evolved around a centrally placed courtyard. Each side features a half-dome open at one end called an iwan.

- Iwan: a rectangular vaulted space in a Muslim building that is walled on three sides and open on the fourth

- Great Mosque in Isfahan, Iran is an example.

- Madrasa: a Muslim school or university often attached to a mosque

- Mausoleum: a building, usually large, that contains tombs

- Minbar: a pulpit from which sermons are given

- Mosque: a Muslim house of worship

- Squinch: the polygonal base of a dome that makes a transition from the round dome to a flat wall

- Voussoirs (pronounced “vōō-swar”): a wedge-shaped stone that forms the curved part of an arch; the central voussoir is called a keystone

➼ The Kaaba

Details

- Islamic and Pre-Islamic monument

- Rededicated by Muhammad in 631–632

- Multiple renovations; granite masonry, covered with silk curtain, and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread

- Found in Mecca, Saudi Arabia

Function

- Mecca is the spiritual center of Islam; this is the most sacred site in Islam.

- A large mosque surrounds the Kaaba.

- Destination for those making the hajj, or spiritual pilgrimage, to Mecca.

- Hajj: an Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca that is required of devout Muslims as one of the five pillars of Islam

- Pilgrims circumambulate the Kaaba counterclockwise seven times.

Materials

- The Kaaba is made of granite; the floor is made of marble and limestone.

- The Kaaba is covered by textiles; the cloth is called the Kiswa and is changed annually.

Context

- Kaaba means cube in Arabic; the Kaaba is cube-like in shape.

- Kaaba said to have been built by Ibrahim (Abraham, in the Western tradition) and Ishamel for God

- Existing structure encases the black stone in the eastern corner, the only part of the original structure by Ibrahim that survives.

- Has been repaired and reconstructed many times since Muhammad’s time.

Image

➼ Dome of the Rock

Details

- Islamic, Umayyad

- 691–692,

- With multiple renovations, stone masonry and wood roof decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome

- Found in Jerusalem

Form

- Domed wooden octagon.

- Influenced by centrally planned buildings

- Columns are spolia taken from Roman monuments.

Function

- Pilgrimage site for the faithful.

- Not a mosque; its original function has been debated.

Context

- This building houses several sacred sites:

- The place where Adam was born.

- The site in which Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac.

- The place where Muhammad ascended to heaven (as described in the Qu’ran).

- The place where the Temple of Jerusalem was located.

- Meant to rival the Christian church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, although it was inspired by its domed rotunda.

- Arabic calligraphy on the mosaic decoration urges Muslims to embrace Allah as the one God and indicates that the Christian notion of the Trinity is an aspect of polytheism.

- Oldest surviving Qur’an verses; first use of Qur’an verses in architecture; one of the oldest Muslim buildings.

- Erected by Abd al-Malik, caliph of the Umayyad Dynasty.

Images

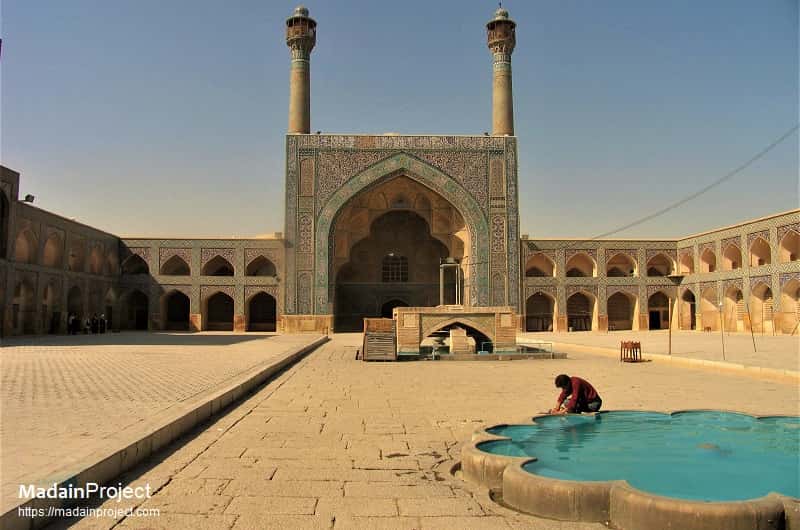

➼ Great Mosque (Masjid-e Jameh)

Details

- Islamic; Persian; Seljuk, Il-Khanid, Timurid, and Safavid Dynasties

- c. 700 additions and restorations in the 14th, 18th, and 20th centuries

- Made of tone, brick, wood, plaster, ceramic tile

- Found in Isfahan, Iran

Form

- Large central rectangular courtyard surrounded by a two-story arcade.

- Typical of Muslim architecture is to have one large arch flanked by two stories of smaller arches

- The qibla iwan is the largest and most decorative; its size indicates the direction to Mecca.

- Southern iwan is an entry for a private space used by the sultan and his retinue; its dome is adorned by decorative tiles; this contains the main mihrab of the mosque.

- Muqarnes: an ornamental and intricate vaulting placed on the underside of arches.

- Elaborately decorated mihrab on the interior points the direction to Mecca; the elaborateness reflects the fact that this is the holiest section of the shrine.

Function

- Muslim mosque.

- Each side of the courtyard, or sahn, has a centrally placed iwan; may be the first mosque to have this feature.

- Sahn: a courtyard in Islamic architecture

- Iwans have different roles, reflecting their size and ornamentation.

Context

- Iwan originally seen in palace architecture; used here for the first time to emphasize the sanctuary.

- This mosque is nestled in an urban center; many gates give access.

- The mosque’s outside walls share support with other buildings.

Images

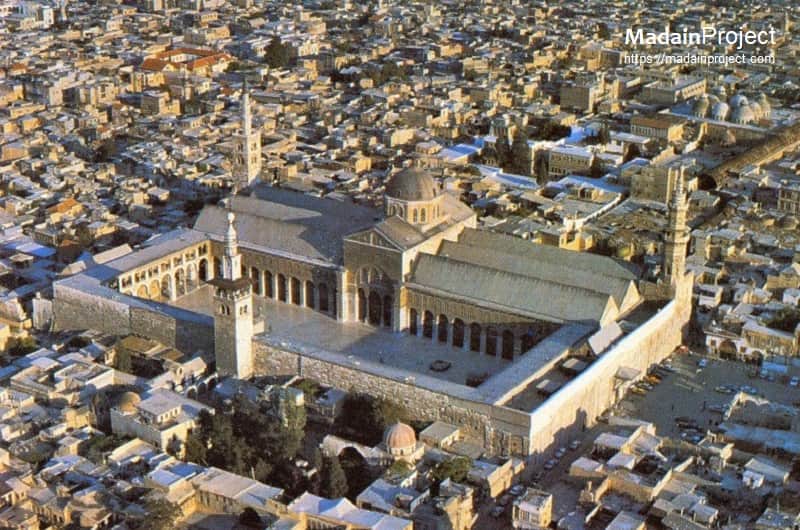

➼ Great Mosque (Umayyad Dynasty)

Details

- Umayyad Dynasty

- 785-786, 8th–10th centuries

- Made of stone masonry

- Foudn in Córdoba, Spain

Form

- Double-arched columns, brilliantly articulated in alternating bands of color.

- Light and airy interior.

- Horseshoe-shaped arches derived from the Visigoths of Spain.

- Hypostyle mosque: no central focus, no congregational worship.

- Elaborately carved doorways signal principle entrances into the mosque and contrast with unadorned walls that otherwise flank the mosque.

Function: Muslim mosque.

History

- The site was originally a Roman temple dedicated to Janus, then a Visigothic church, and then the mosque was built.

- Columns are spolia from ancient Roman structures.

- After a Christian reconquest, the center of the mosque was used for a church.

- Original wooden ceiling replaced by vaulting after Spanish reconquest.

Context

- Complex dome with elaborate squinches was built over the mihrab; it was inspired by Byzantine architecture.

- Horseshoe-shaped arches were inspired by Visigothic buildings in Spain.

- Relatively short columns made ceilings low; doubling of arches enhances interior space, perhaps influenced by the Roman aqueduct in Mérida, Spain.

- Kufic calligraphy on walls and vaults.

- Original patron: Abl al Rahman.

Images

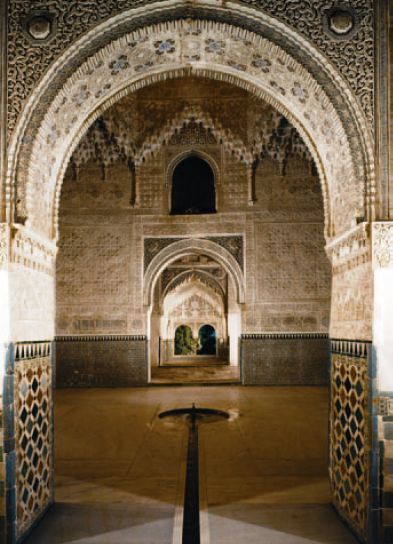

➼ Alhambra

Details

- Nasrid Dynasty

- 1354–1391

- Made of whitewashed adobe stucco, wood, tile, paint, and gilding

- Found in Granada, Spain

Form

- Light, airy interiors; fortress-like exterior.

- Contains palaces, gardens, water pools, fountains, courtyards.

- Small, low-bubbling fountains in each room contribute to cool temperatures in the summer.

- Inspired by the Charbagh gardens from Persia.

- Charbagh: a rectangular garden in the Persian tradition that is based on the four gardens of Paradise mentioned in the Qur’an

Function

- Palace of the Nasrid sultans of southern Spain.

- The Alcazaba (Arab for fortress) is the oldest section and is visible from the exterior.

- The Alcazaba is a double-walled fortress of solid and vaulted towers containing barracks, cisterns, baths, houses, storerooms, and a dungeon.

Context: Built on a hill overlooking the city of Granada.

Image

➼ Court of the Lions

Form

- Thin columns support heavy roofs; a feeling of weightlessness.

- Intricately patterned and sculpted ceilings and walls.

- Central fountain supported by 12 protective lions; animal imagery permitted in secular monuments.

- Parts of the walls are chiseled through to create vibrant light patterns within.

Context

- Built by Muhammad V between 1370 and 1391.

- Palaces follow the tradition of western Islamic palace design: rooms arranged symmetrically around rectangular courtyards.

- The courtyard is divided into four parts, each symbolizing one of the four parts of the world.

- Each part of the world is therefore irrigated by a water channel that symbolizes the four rivers of Paradise.

- The courtyard is an architectural symbol of Paradise combining its gardens, water, and columns in a unified expression.

Image

➼ Hall of the Sisters

Form

- Sixteen small windows are placed at the top of hall; light dissolves into a honeycomb of stalactites hanging from the ceiling.

- Five thousand muqarnas, carved in stucco onto the ceiling, refract light.

- Abstract patterns, abstraction of forms.

- Highly sophisticated and refined interior.

Context

- Perhaps used as a music room or for receptions.

- The hall is so named because of two big twin marble flagstones placed on the floor.

- In between these flagstones is a small fountain and a short canal from which water flows to the Court of the Lions.

- The hall was built by order of Mohammed V.

Image

➼ Mosque of Selim II

Details

- By Mimar Sinan

- 1568–1575

- Made of brick and stone,

- Found in Edirne, Turkey

Form

- Extremely thin soaring minarets.

- Abundant window space makes for a brilliantly lit interior.

- Octagonal interior, with eight pillars resting on a square set of piers.

- Squinches decorated with muqarnas transition the round dome to the huge piers below.

- Smaller half-domes in the corners support the main dome and transition the space to a square ground plan.

- Decorative display of Iznik mosaic and tile work.

Function: Mosque part of a complex, including a hospital, school, and library.

Context

- Inspired by Hagia Sophia, but a centrally planned building.

- Open airy interior contrasts with conventional mosques that have partitioned interiors.

- Sinan was chief court architect for the Ottoman emperor Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566).

Images

➼ Taj Mahal

- Details

- c. 1632–1653

- Made of stone masonry and marble with inlay of precious and semi-precious stones, garden

- Found in Uttar Pradesh, Agra, India

- Form

- Symmetrical harmony of design.

- Typical Islamic feature of one large central arch flanked by two smaller arches

- Square plan with chamfered corners.

- Onion-shaped dome rises gracefully from the façade.

- Small kiosks around dome lessen severity.

- Intricate floral and geometric inlays of colored stone.

- Minarets act like a picture frame, directing the eye of the viewer and sheltering the monument.

- Texts from the Qu’ran cover surface.

- Motifs of flowering plants, carved into the walls of the structure, may have been inspired by engravings in European herbals.

- Function: Built as the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan’s wife; the shah was interred next to her after his death.

- Context

- Translated to mean “crown palace.”

- Named for Mumtaz Mahal, deceased wife of Shah Jahan, who died while giving birth to her 14th child.

- Part of a larger ensemble of buildings.

- Grounds represent a vast funerary garden, the gardens found in heaven in the Islamic tradition.

- Taj Mahal reflected in the Charbagh garden

- Different from other Mongol buildings in its extensive use of white marble, which was generally reserved for interior spaces; white marble contrasts with the red sandstone of the flanking buildings.

- Influence of Hindi texts in which white is seen as a symbol of purity for priests and red for warriors; the Taj Mahal is white marble but the surrounding buildings are red sandstone.

- Theory

- May have been built to salute the grandeur of the Shah Jahan and his royal kingdom, as much as to honor his wife’s memory.

- Alternate theory suggests that this is a symbolic representation of a Divine Throne on the Day of Judgment.

Images