Study Guide | Module 2.7 [Forgetting] | AP Psych Unit 2

happy studying!

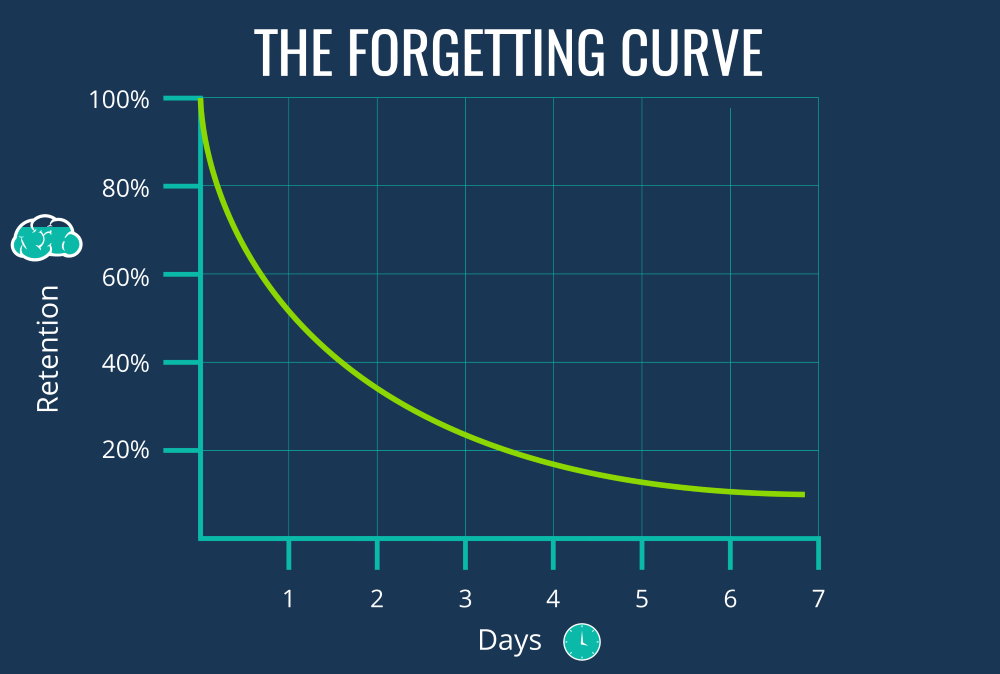

Forgetting Curve

The forgetting curve is a theory proposed by psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus that demonstrates the decline of memory retention over time. The curve shows that after learning something new, we forget the majority of the information rapidly in the first few hours or days. However, after this initial drop, the rate of forgetting slows down, and what is retained in memory stabilizes over time. The curve suggests that most forgetting happens soon after the information is learned and that repeated review or rehearsal can help retain information for longer periods.

Example 1: After studying for a test, you might forget a lot of the material within the first 24 hours, but the information you remember after that point will be easier to retain with further study.

Example 2: If you learn a new phone number but forget most of it within a few days, the bits of the number you retain are likely to stay in your memory longer with periodic rehearsal.

The forgetting curve emphasizes the natural process of memory decay, showing that without reinforcement or review, our memories tend to fade over time. It also highlights the importance of repetition in improving long-term memory retention.

Encoding Failure

Occurs when information does not get stored in memory because we fail to pay enough attention or process it deeply enough. For information to be stored in long-term memory, it must first be encoded—meaning it must be converted into a format that can be saved. If this step is skipped or insufficient, we may forget the information later, even though it was initially perceived.

Example 1: You meet someone new and are introduced to them by name, but you’re distracted and not really paying attention. Later, when you try to recall their name, you can’t remember it. This is because the name wasn’t properly encoded into your memory due to lack of attention.

Example 2: You walk past a familiar object every day, like a clock in your house, but you never really focus on it. When asked about the details of the clock, like its design or color, you may not be able to recall them. The information about the clock wasn’t deeply processed or encoded because you didn’t actively think about it.

In both examples, the information didn’t get fully processed or encoded, so it wasn’t stored in memory, leading to forgetting. Encoding failure shows how our brains filter out irrelevant or unimportant details, leading to gaps in what we remember.

Proactive Interference

Refers to the disruption of the recall of new information due to previously learned information. Essentially, older memories or behaviors can "get in the way" of remembering new information. This type of memory interference shows how prior learning can continue to affect how we encode or retrieve new experiences or details.

Example 1: If you recently learned your teacher’s married name, but you continue to call her by her maiden name, the memory of her old name interferes with your ability to remember and use her new name.

Example 2: If you’ve always driven a certain route to school and then try a new route, your habit of using the old route may make it difficult to remember or follow the new one initially.

Proactive interference demonstrates how established memories can sometimes hinder our ability to adapt to new information and memories, making it harder to recall new details when they conflict with old ones.

Retroactive Interference

Occurs when newer information disrupts the ability to recall older information. In this case, more recent memories interfere with the retrieval of previously learned memories, making it harder to remember things from the past. This type of interference happens when the new information "overwrites" or competes with older memories, particularly when they are similar.

Example 1: After moving to a new house, you might struggle to recall your old address because the new address has replaced it in your memory, interfering with the recall of the previous one.

Example 2: If you start using a new phone number, you might have trouble remembering your old number, as the new one interferes with your ability to retrieve the old one.

Retroactive interference shows how new learning can disrupt older memories, making it challenging to recall past experiences or information once new details are learned and stored in the brain.

Retrieval Failure

Happens when we cannot access information that is stored in our memory. Even though the memory is there, we cannot find it at the moment. This can occur when we lack the proper retrieval cues, when other memories interfere, or when the memory is not strong enough to be easily retrieved.

Example 1: You’ve studied for a test, but when you’re taking it, you can’t recall key terms even though you studied them. The memory is there, but you just can’t find it because the right cues aren’t available during the test.

Example 2: You try to recall the name of a movie you watched last year. You know the plot and actors, but the name doesn’t come to you. The memory exists in your brain, but you can’t access it without the right cue or context.

Retrieval failure illustrates how sometimes, despite having information stored in memory, we may not be able to retrieve it without the right triggers or conditions.

Tip-of-the-Tongue Phenomenon

Occurs when you feel like you know a word or piece of information, but you cannot quite recall it. You know it's in your memory, but it’s temporarily inaccessible. This feeling of "almost remembering" is often accompanied by a sense of frustration as your brain tries to retrieve the word or memory. This phenomenon shows how our memory retrieval can sometimes be blocked, even when the information is right there.

Example 1: You’re talking to someone and suddenly can’t remember a word you use frequently, like the name of a book or movie. You can picture the word, but it just won’t come to you, even though you know you know it.

Example 2: You’re trying to recall the name of a person you met at a party, and even though you know it’s on the tip of your tongue, you can’t remember it no matter how hard you try.

The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon occurs when the memory is stored in your brain but you cannot access it because the correct retrieval cues aren’t available, or the memory is temporarily blocked. This experience is common and reflects the sometimes complex nature of memory retrieval.

Motivated Forgetting / Repression (Psychodynamic)

Motivated forgetting, also known as repression, is a concept from psychodynamic theory, which suggests that people may forget or block memories of painful or traumatic events in order to protect themselves from emotional distress. These memories are not deliberately forgotten, but rather pushed out of conscious awareness because they are too overwhelming or anxiety-inducing to face. According to Sigmund Freud, repression helps individuals cope with memories that may be too threatening or difficult to confront.

Example 1: A person who experienced a traumatic accident in childhood might repress the memory of the event. As a result, they may not consciously remember the event, though it may still influence their behavior or emotions without their awareness.

Example 2: A person who was emotionally abused as a child may repress the painful memories of that abuse. Over time, the memories may be so deeply buried that they no longer consciously remember the abuse, even though it could affect their adult relationships and emotional responses.

Motivated forgetting/repression shows how the mind can shield itself from memories that would cause too much psychological harm, though these repressed memories might still impact behavior unconsciously.

Anterograde Amnesia

A type of memory loss where an individual is unable to form new memories after experiencing brain injury or trauma. While they can still recall memories from before the incident, their ability to create new long-term memories is impaired. This condition occurs when the brain's ability to encode and store new information is disrupted, often due to damage to areas like the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory formation.

Example 1: A person with anterograde amnesia might meet someone new and forget their name shortly afterward. They may not be able to remember the interaction later, even though they were fully aware of it at the time.

Example 2: A person who suffers from anterograde amnesia after a head injury may remember their childhood and important past events but cannot retain new information, such as what happened the previous day or who visited them in the hospital.

Anterograde amnesia illustrates how specific areas of the brain are responsible for different aspects of memory. It highlights how the brain's ability to store new experiences can be disrupted while older memories remain intact, showing the complex and specialized nature of memory systems.

Retrograde Amnesia

The inability to recall memories from before a specific event, such as a traumatic brain injury or accident. The memories that are lost typically include information from a period leading up to the event, while the ability to form new memories after the event is often unaffected. This type of amnesia is thought to result from damage to areas of the brain involved in memory storage, like the hippocampus or the cortical areas related to long-term memory.

Example 1: After a person experiences a head injury from a fall, they may forget events from the past few years, including important dates, people they met, or specific experiences, but they can still remember childhood memories or form new ones going forward.

Example 2: Someone who suffers retrograde amnesia after a traumatic event may forget their wedding day, but they can still recall memories from their childhood and begin making new memories post-accident.

Retrograde amnesia demonstrates how memories can be lost from the past while the brain’s ability to create new memories can remain intact. It highlights the differences between memory systems involved in recalling past events versus encoding new experiences.

Infantile Amnesia

The inability to recall events from early childhood, typically before the age of 3 or 4. This is believed to occur because the brain structures involved in long-term memory storage, such as the hippocampus, are not fully developed during this period. Additionally, language skills, which play a key role in encoding and recalling memories, are still emerging during infancy, making it harder to create lasting memories from this stage of life.

Example 1: A person may not be able to recall their first words or memories of their early family interactions, as their language skills and memory systems were not fully developed at the time.

Example 2: A child’s inability to remember early experiences, like their first trip to the zoo, may be linked to the immature state of their brain and lack of a developed language system to process and store such memories.

Infantile amnesia illustrates the critical role of brain development and language acquisition in memory formation, emphasizing how both the brain's maturation and language skills are necessary for retaining and recalling early experiences.

Source Amnesia

Occurs when an individual is able to remember the information itself but cannot recall the context in which they learned it, such as the time, place, or person that provided the information. This type of memory error reflects a disconnect between the content of the memory and the source of that information. Source amnesia can happen when the brain fails to properly encode or store contextual details while focusing on the factual content.

Example 1: You might clearly remember a historical fact but cannot recall whether you learned it in school, from a friend, or through media.

Example 2: You remember a joke you heard but are unable to recall who told it to you or when you heard it, even though you can still retell the joke itself.

Source amnesia highlights how the brain can separate the factual content of memories from the details about their origins, showing that memory is not always perfect in recalling both information and its context.

Misinformation Effect

Occurs when misleading or incorrect information influences or distorts a person's memory of an event. This phenomenon shows how memory is not always accurate and can be shaped by external factors, such as suggestion or the introduction of false details. The misinformation effect is a key concept in understanding the malleability of memory, especially in situations where individuals may be exposed to incorrect or suggestive information after the original event.

Example 1: If a witness to a crime is asked leading questions about a suspect's appearance, they may later recall the details of the suspect differently than they originally remembered due to the influence of the misleading questions.

Example 2: After hearing news reports about a robbery that mention a red car, you might later falsely remember seeing a red car at the scene, even if it was never there.

The misinformation effect illustrates the vulnerability of human memory, showing how external influences can change or create false memories, leading individuals to recall events inaccurately.

Constructive Memory

Constructive memory refers to the process by which our brain actively constructs or "builds" memories by filling in missing details based on prior knowledge, expectations, and suggestions. This process can lead to the creation of false or distorted memories, as the brain blends real experiences with imagined or external information. While this ability helps us make sense of incomplete information, it also makes our memories less reliable and subject to inaccuracies.

Example 1: After repeatedly hearing about a family vacation, you may come to "remember" details of the trip, even if they never actually happened, simply because you've heard the story many times.

Example 2: You might recall a conversation you had with a friend, but over time, your memory of the conversation could include details that were actually part of a different conversation, blending memories together.

Constructive memory highlights how memory is not a perfect recording of past events but is an active process of reconstruction. This can make memories subject to distortion, leading to the creation of false or modified recollections.

Memory Consolidation

The process through which short-term memories are stabilized and converted into long-term memories. This transformation occurs through neural activity and repeated rehearsal, which strengthen the connections between neurons in the brain. Consolidation is essential for making memories more durable and accessible over time. It is particularly active during sleep, when the brain replays and solidifies new information.

Example 1: When you study for an exam and review the material multiple times, the information gradually becomes more firmly stored in your long-term memory, making it easier to recall on test day.

Example 2: After learning a new skill, such as riding a bike, memory consolidation helps "solidify" the learning experience, making it something you can recall and perform without consciously thinking about each step.

Memory consolidation demonstrates how active and ongoing processes in the brain help us store and maintain memories for the long term, emphasizing the importance of repetition and sleep in the retention of new information.

Imagination Inflation

Occurs when a person vividly imagines an event, which can lead them to believe it actually happened, even if it did not. This phenomenon highlights how mental imagery can distort memory and cause individuals to mistakenly recall imagined events as real. The process occurs because when we vividly imagine something, the brain often does not distinguish between actual experiences and imagined ones, leading to a blending of memory and imagination.

Example 1: After repeatedly imagining a scenario in which you met a famous person, you may later recall the event as a real memory, even though it only occurred in your imagination.

Example 2: A person may falsely "remember" a family vacation they never took simply by vividly imagining the trip over time or hearing about it from others.

Imagination inflation demonstrates the malleability of memory and how the act of mentally rehearsing or imagining an event can alter a person's memory, potentially leading to the creation of false memories.