Dealing with offending behavior: Custodial sentencing

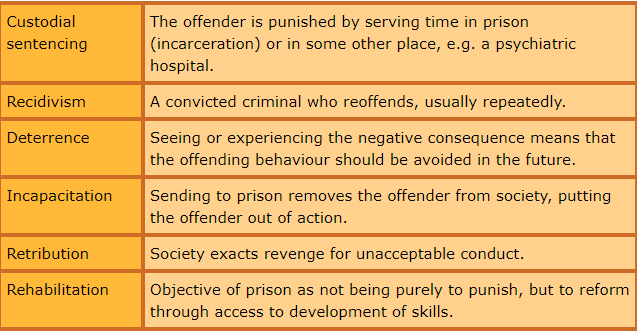

Key terms

Custodial sentencing - A judicial sentence determined by a court, where the offender is punished by serving time in prison (incarceration) or in some other closed therapeutic and/or educational institution such as psychiatric hospital.

Recidivism - Reoffending, a tendency to relapse into a previous condition or mode of behavior; in the context of crime, a convicted criminal who reoffends, usually repeatedly.

Custodial sentencing

The aims of custodial sentencing

Custodial sentencing - involves a convicted offender spending time in prison or another closed institution such as a young offender’s institute or psychiatric hospital, there are 4 main reasons for doing this.

1 - Deterrence

The unpleasant prison experience is designed to put off the individual (or society at large) from engaging in offending behavior. Deterrence works on two levels

General deterrence - aims to send a broad message to members of a given society that crime will not be tolerated.

Individual deterrence - should prevent the individual from repeating the same crime in light of their experience. In other words, this view is based on the behaviorist idea of conditioning through punishment.

2 - Incapacitation

The offender is taken out of society to prevent them reoffending as a means of protecting the public. The need for incapacitation is likely to depend upon the severity of the offence and the nature of the offender. For instance, individuals in society will require more protecting from a serial murderer or rapist than an elderly person who refuses to pay for their council tax.

3 - Retribution

Society is enacting revenge for the crime by making the offender suffer, and the level of suffering should be proportionate to the seriousness of the crime. This is based on the biblical notion of an ‘eye for eye’, that the offender should in some way pay for their actions. Many people see prison as the best possible option in this sense and alternative to prison are often criticized as soft options.

4 - Habilitation

In contrast, many commentators would see the main objective of prison as not being purely to punish, but to reform. Upon release, offender should leave prison better adjusted and ready to take place back in society. Prison should provide opportunities to develop skills and training or to access treatment programmes for drug addiction, as well as give the offenders the chance to reflect on their crime.

The psychological effects of custodial sentencing

Stress and depression

Suicide rates are considerably higher in prison than in the general population, as are incidents of self-mutilation and self-harm. The stress of the prison experience also increases the risk of psychological disturbance following release.

Institutionalization

Having adapted to the norms and the routines of prison life, inmates may become so accustomed to these that they are no longer able to function on the outside.

Prisonisation

This refers to the way in which prisoners are socialized into adopting as ‘inmate code’. Behaviour that may be considered unacceptable in the outside world may be encouraged and rewarded inside the walls of the intuition.

The problem of recidivism

Recidivism - refers to reoffending.

Statistics produced by the Ministry of Justice in 2013 suggest that 57% of UK offenders will reoffend within a year of release. In 2017, 14 prisons recorded reoffending rates of over 70%. Although statistics vary according to type of offence, the UK and US both have some of the highest rates of recidivism in the world. This is stark contrast to Norway where reoffending rates are the lowest in Europe and and less than half of those in the UK. Penal institutions are much more open in Norway and there is much greater emphasis placed on rehabilitation and skills development than there is in the UK. However, many commentators are very critical of the Norwegian model labelling it a soft opening that does not sufficiently punish its inmates.

Evaluation

Evidence supports psychological effects

Curt Bartol (1995) has suggested that for many offenders, imprisonment can be ‘brutal, demeaning and generally devastating.’ In the last 20 years, suicide rates among offenders have tended to be around 15 times higher than those in the general population. Most at risk are young single men during the first 24 hours of confinement. A recent study conducted by the Prison Reform Trust (2014) found that 25% of women and 15% of men in prison reported symptoms indicative of psychosis. It would seem that the oppressive prison regime may trigger psychological disorders in those that are vulnerable. This suggests that custodial sentencing is not effective in rehabilitating the individual, particularly those who are psychologically vulnerable.

Individual differences

Although time in prison may be psychologically challenging for many, it cannot be assumed that all offenders will react in the same way. Different prisons have different regimes, so there are likely to be wide variations in experience. In addition, the length of sentence, the reason for incarceration and previous experience of prison may all be important mitigating factors. Finally, many of those convicted may have had pre-existing psychological and emotional difficulties at the time they were convicted (and this may explain their offending behaviour in the first place)

Therefore it is difficult to make general conclusions that apply to every prisoner and every prison.

Opportunities for training and treatment

The rehabilitation model is based on the argument that offenders may become better people during their time in prison, and their improved character means they are able to lead a crime-free life when they come back to society. Many prisoners access education and training whilst in prison increasing the possibility they will find employment upon release. Also, treatment programmes such as anger management schemes and social skills training may give offenders insight into their behaviour, reducing the likelihood of recidivism.

This suggest prison may be a worthwhile experience assuming offenders are able to asses these programmes, however many prisons may lack the resources to provide these resources and even when they can, evidence to support the long-term benefits of such schemes is not conclusive.

Universities for crime

Alongside the legitimate skills that offenders may acquire during prison, they may also undergo learning crime within the prison from more experienced offenders, this may undermine attempts of rehabilitate prisoners, making reoffending more likely.

This supports the differential association theory of crime. Differential association theory proposes that through interaction with others, individuals learn the values, attitudes, techniques, and motives for criminal behaviour. Sutherland argues that if the number of pro-criminal attitudes the person comes to acquire outweighs the number of anti-criminal attitudes, they will go on to offend. Sutherland’s theory can also account for why so many convicts released from prison go on to reoffend. It is reasonable to assume that whilst ‘inside’, inmates will learn specific techniques of offending from other, more experienced criminals that they may be eager to put into practice upon their release.

Alternatives to custodial sentencing

Judge Geoffrey Davies and co Autor Raymond (2000) in a review of custodial sentencing, concluded that government ministers often exaggerate the benefits of prison in a bid to appear tough on crime. The review suggested that prison does little to deter others or rehabilitate offenders, such as community service and restorative justice, have been proposed which mean family contacts and perhaps employment can be maintained.

One of the aims of restorative justice is about the offender changing the way they view their behaviour, requiring them to apologise their actions and pay reparation, for example through repairing the damage done or paying compensation. This is likely to have a big impact on recidivism whereas incarceration does not really deal with the root problem.

Restorative justice may also reduce recidivism rates, as they do not learn from other criminals in prison.

Restorative justice has the advantage criminals can remain in the community so can uphold jobs and family relationships, which they could not do in prison. This may therefore be suitable for first-time offenders or non-violent offenders that are not a threat to the public.

However, it may not be suitable for all types of crime, e.g. for rape and murder, where criminals may be a danger to the public.

The community may not feel that the criminal has been punished and may feel it is not a sufficient deterrent.