Bio112 Exam 1 Study Guide

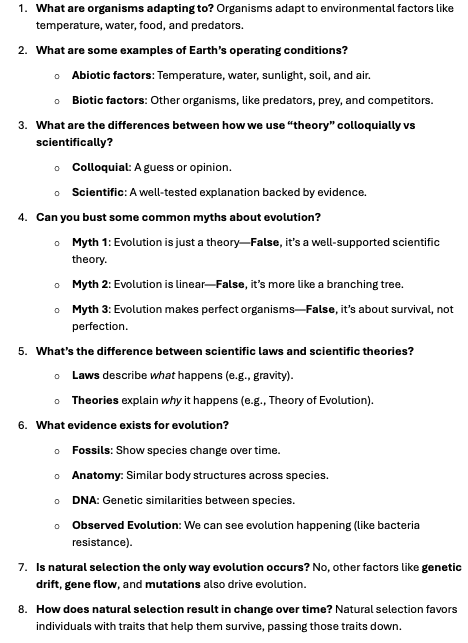

What are organisms adapting to? Organisms adapt to environmental factors like temperature, water, food, and predators.

What are some examples of Earth’s operating conditions?

Abiotic factors: Temperature, water, sunlight, soil, and air.

Biotic factors: Other organisms, like predators, prey, and competitors.

What are the differences between how we use “theory” colloquially vs scientifically?

Colloquial: A guess or opinion.

Scientific: A well-tested explanation backed by evidence.

Can you bust some common myths about evolution?

Myth 1: Evolution is just a theory—False, it’s a well-supported scientific theory.

Myth 2: Evolution is linear—False, it’s more like a branching tree.

Myth 3: Evolution makes perfect organisms—False, it’s about survival, not perfection.

What’s the difference between scientific laws and scientific theories?

Laws describe what happens (e.g., gravity).

Theories explain why it happens (e.g., Theory of Evolution).

What evidence exists for evolution?

Fossils: Show species change over time.

Anatomy: Similar body structures across species.

DNA: Genetic similarities between species.

Observed Evolution: We can see evolution happening (like bacteria resistance).

Is natural selection the only way evolution occurs? No, other factors like genetic drift, gene flow, and mutations also drive evolution.

How does natural selection result in change over time? Natural selection favors individuals with traits that help them survive, passing those traits down.

What is the raw material within populations that natural selection works with? Genetic variation (differences in genes within a population).

What is evolving (smallest unit)? Populations evolve, not individual organisms.

How quickly does evolution occur? It can happen quickly (in bacteria) or slowly (in large animals), depending on factors like mutation rates and environmental changes.

What factors affect and constrain the speed of evolutionary change?

Mutation rates

Population size

Environmental pressures

Generation time

Do you think it’s likely humans will evolve a third arm? Why or why not? Unlikely. Evolution requires specific genetic changes that give an advantage. A third arm isn’t needed for survival.

What factors limit evolutionary change?

Genetic constraints: Some traits are harder to evolve.

Environmental stability: Little change means no evolutionary pressure.

Small population sizes: Can lose beneficial traits due to genetic drift.

Can you give an example of a fitness trade-off?

A bird with larger beaks may be better at eating hard seeds but less agile, making it more vulnerable to predators.

Can an organism ever be perfectly adapted? No, organisms are always adapting to changing environments, and trade-offs exist.

Are all traits adaptive? No, some traits may be neutral or even harmful (e.g., harmful mutations).

Distinguish between directional, diversifying, and stabilizing selection.

Directional: Favors one extreme trait (e.g., bigger beaks).

Diversifying/Disruptive: Favors both extremes (e.g., small and large beaks).

Stabilizing: Favors the middle trait (e.g., medium-sized beaks).

Give examples of intra- and inter-sexual selection and how they cause sexual dimorphism.

Intra-sexual: Males fighting for mates (e.g., deer antlers).

Inter-sexual: Females choosing mates based on traits (e.g., peacock feathers).

Which aspects of evolutionary change are random? Which are not?

Random: Mutations, genetic drift.

Not random: Natural selection, gene flow.

Distinguish between genetic drift and gene flow.

Genetic drift: Random changes in allele frequencies (especially in small populations).

Gene flow: Movement of genes between populations.

Distinguish between a genetic bottleneck and the founder effect.

Genetic bottleneck: A sharp reduction in population size, leading to loss of genetic variation.

Founder effect: When a small group of individuals establishes a new population with limited genetic variation.

How might the founder effect create opportunities for adaptive radiation? Small groups can quickly adapt to different environments, leading to many new species.

Would isolation of a large or small population size be more likely to result in speciation? Small populationsare more likely to experience genetic changes leading to speciation due to genetic drift and limited gene flow.

Would higher gene flow between populations increase or decrease the likelihood of speciation? Decrease. More gene flow reduces differences between populations, making speciation less likely.

What parameters must be occurring if a population (or alleles) is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium?

No mutation

Random mating

No natural selection

Large population size

No gene flow

Compare and contrast allopatric and sympatric speciation.

Allopatric: Speciation due to physical separation (e.g., mountains).

Sympatric: Speciation without physical barriers (e.g., different mating habits).

When is the biological species concept better than the morphological species concept? The biological species concept works best when it’s hard to tell species apart by shape but they don’t interbreed (e.g., cryptic species).

What keeps closely related species separate? Prezygotic barriers (before fertilization) like mating season differences, and postzygotic barriers (after fertilization) like hybrid sterility.

30. · Phylogenetic tree: A diagram showing the evolutionary relationships between different species based on common ancestors.

31. · Population: A group of individuals of the same species living in the same area and interbreeding.

32. · Transition species: Fossils or organisms that show intermediate characteristics between two groups, showing evolutionary change (e.g., Archaeopteryx, between dinosaurs and birds).

33. · Vestigial (rudimentary) traits: Features that have lost their original function through evolution (e.g., human tailbone, whale pelvis).

34. · Homologous structures: Similar structures in different species due to common ancestry (e.g., human arm, bat wing, whale flipper).

35. · Analogous structures: Similar structures in different species due to similar functions, not common ancestry (e.g., wings of a bird and a butterfly).

36. · Biogeography: The study of how species are distributed across different geographical regions and how this relates to evolutionary history.

37. · Developmental homology: Similarities in the embryonic development of different species due to shared ancestry (e.g., all vertebrate embryos having gill slits).

38. · Structural homology: Similarities in body structures due to shared ancestry (e.g., the similar bone structure in vertebrate limbs).

39. · Adaptation: A trait that increases an organism’s chance of survival and reproduction in a particular environment.

40. · Allele: Different forms of a gene found at the same location on a chromosome (e.g., an allele for blue eyes vs. brown eyes).

41. · Mutation: A random change in DNA that can introduce new genetic variation.

42. · Variation: Differences in traits (such as color, size, etc.) within a population.

43. · Gene pool: The total collection of genes and alleles present in a population.

44. · Natural selection: The process where organisms with traits that better suit their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce.

45. · Fitness: An organism’s ability to survive and reproduce in its environment.

46. · Fitness trade-off: A situation where a beneficial trait in one area may come at a cost in another area (e.g., large size for better survival, but slower speed).

47. · Directional selection: A type of natural selection where one extreme trait is favored (e.g., bigger beaks in birds).

48. · Stabilizing selection: A type of natural selection that favors the average trait, reducing variation (e.g., average birth weight in humans).

49. · Disruptive/diversifying selection: A type of natural selection that favors both extremes of a trait and can lead to two distinct phenotypes (e.g., small and large beaks in birds, but not medium-sized).

50. · Sexual selection: A type of natural selection where traits increase an individual's chances of mating (e.g., peacock’s colorful feathers).

51. · Sexual dimorphism: Differences in appearance between males and females of the same species due to sexual selection (e.g., size differences between male and female lions).

52. · Genetic drift: Random changes in allele frequencies in a population, often having a larger effect in small populations.

53. · Gene flow: The movement of alleles between populations through migration, which can increase genetic diversity.

54. · Genetic bottleneck: A sharp reduction in a population's size, leading to a loss of genetic diversity.

55. · Founder effect: When a small group of individuals starts a new population, the gene pool is limited to the genetic diversity of the founders.

56. · Genotype: The genetic makeup of an individual organism (e.g., the alleles it carries).

57. · Phenotype: The physical or observable traits of an organism, which are influenced by its genotype and environment.

58. · Allele frequency: The proportion of a particular allele in a population's gene pool.

59. · Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium: A model that predicts allele frequencies will remain constant if no evolutionary forces (like natural selection, mutation, etc.) act on a population.

60. · Biological species: A species defined by the ability of individuals to interbreed and produce fertile offspring.

61. · Morphological species: A species defined by physical characteristics, often used when reproductive isolation is unclear.

62. · Prezygotic isolation: Barriers that prevent mating or fertilization from occurring, such as differences in mating behavior or timing.

63. · Postzygotic isolation: Barriers that occur after fertilization, such as hybrid inviability, sterility, or breakdown.

64. · Hybrid: The offspring of two different species or varieties.

65. · Hybrid inviability: When hybrid offspring do not survive to maturity due to genetic incompatibility.

66. · Hybrid sterility: When hybrid offspring are born but cannot reproduce (e.g., mules, which are hybrids of horses and donkeys).

67. · Hybrid breakdown: When the offspring of hybrids are fertile but their descendants suffer from genetic problems.

68. · Allopatric speciation: Speciation that occurs when a population is geographically separated, leading to reproductive isolation and new species.

69. · Sympatric speciation: Speciation that occurs without geographic isolation, often due to behavioral, ecological, or genetic factors.

70. · Autopolyploidy: A form of speciation where an organism has more than two sets of chromosomes from the same species, often leading to reproductive isolation.

71. · Allopolyploidy: A form of speciation where an organism has multiple sets of chromosomes from different species, resulting in hybrid offspring that can reproduce.

ch18 Evolution is the process of adaptation through mutation which allows more desirable characteristics to pass to the next generation. Over time, organisms evolve more characteristics that are beneficial to their survival. For living organisms to adapt and change to environmental pressures, genetic variation must be present. With genetic variation, individuals have differences in form and function that allow some to survive certain conditions better than others. These organisms pass their favorable traits to their offspring. Eventually, environments change, and what was once a desirable, advantageous trait may become an undesirable trait and organisms may further evolve. Evolution may be convergent with similar traits evolving in multiple species or divergent with diverse traits evolving in multiple species that came from a common ancestor. We can observe evidence of evolution by means of DNA code and the fossil record, and also by the existence of homologous and vestigial structures. 18.2 Formation of New Species Speciation occurs along two main pathways: geographic separation (allopatric speciation) and through mechanisms that occur within a shared habitat (sympatric speciation). Both pathways isolate a population reproductively in some form. Mechanisms of reproductive isolation act as barriers between closely related species, enabling them to diverge and exist as genetically independent species. Prezygotic barriers block reproduction prior to formation of a zygote; whereas, postzygotic barriers block reproduction after fertilization occurs. For a new species to develop, something must introduce a reproductive barrier. Sympatric speciation can occur through errors in meiosis that form gametes with extra chromosomes (polyploidy). Autopolyploidy occurs within a single species; whereas, allopolyploidy occurs between closely related species. 18.3 Reconnection and Speciation Rates Speciation is not a precise division: overlap between closely related species can occur in areas called hybrid zones. Organisms reproduce with other similar organisms. The fitness of these hybrid offspring can affect the two species' evolutionary path. Scientists propose two models for the rate of speciation: one model illustrates how a species can change slowly over time. The other model demonstrates how change can occur quickly from a parent generation to a new species. Both models continue to follow natural selection patterns.

Evolution (Ch 18)

Evolution: Process of adaptation through mutation, where desirable characteristics are passed to the next generation, increasing survival chances.

Genetic variation: Crucial for evolution, providing differences in traits (form and function) that help some individuals survive better under certain conditions.

Beneficial traits: These traits get passed on to offspring, improving the survival of the population over time.

Environmental change: What is beneficial today may become a disadvantage later, prompting further evolution.

Convergent evolution: Similar traits evolve in different species (e.g., wings in birds and bats).

Divergent evolution: Different traits evolve in species from a common ancestor (e.g., different beak shapes in Darwin's finches).

Evidence for evolution:

DNA code: Similarities in DNA between species.

Fossil record: Shows gradual changes over time.

Homologous structures: Similar structures in different species from a common ancestor.

Vestigial structures: Remnants of features that no longer serve a function (e.g., human tailbone).

Formation of New Species

Speciation: The formation of new species, occurring via two pathways:

Allopatric speciation: Geographic separation isolates populations, leading to speciation.

Sympatric speciation: Speciation within the same habitat, often due to reproductive barriers.

Reproductive isolation: Mechanisms that prevent interbreeding between populations, leading to speciation:

Prezygotic barriers: Block reproduction before fertilization (e.g., different mating behaviors or timing).

Postzygotic barriers: Block reproduction after fertilization (e.g., hybrid inviability, hybrid sterility).

Polyploidy (mechanism of sympatric speciation):

Autopolyploidy: Extra chromosomes within a single species.

Allopolyploidy: Extra chromosomes between closely related species.

Reconnection and Speciation Rates

Hybrid zones: Areas where closely related species overlap and interbreed, producing hybrids.

Hybrid offspring: Their fitness can influence the evolutionary paths of the parent species.

Speciation rates:

Gradual model: Species evolve slowly over time.

Punctuated model: Rapid changes from a parent generation to a new species, followed by long periods of little change.

Both models follow natural selection patterns and contribute to the diversity of life.

Review Questions Answers

4. Which scientific concept did Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace independently discover?

b. natural selection

5. Which of the following situations will lead to natural selection?

d. all of the above

(All situations involve a selective advantage or disadvantage leading to natural selection.)

6. Which description is an example of a phenotype?

d. both a and c

(A duck’s blue beak and cheetahs living solitary lives are both phenotypic traits.)

7. Which situation is most likely an example of convergent evolution?

d. all of the above

(Squid, worms, bats, and birds all evolved similar traits, like eyes or wings, but from different evolutionary paths.)

8. Which situation would most likely lead to allopatric speciation?

a. Flood causes the formation of a new lake.

(This creates geographic isolation between populations.)

9. What is the main difference between dispersal and vicariance?

b. One involves the movement of the organism, and the other involves a change in the environment.

(Dispersal: movement of organisms; Vicariance: environmental changes cause separation.)

10. Which variable increases the likelihood of allopatric speciation taking place more quickly?

b. longer distance between divided groups

(Greater distance increases isolation, speeding up speciation.)

11. What is the main difference between autopolyploid and allopolyploid?

c. the source of the extra chromosomes

(Autopolyploidy: extra chromosomes within the same species; Allopolyploidy: extra chromosomes from different species.)

12. Which reproductive combination produces hybrids?

c. when members of closely related species reproduce

13. Which condition is the basis for a species to be reproductively isolated from other members?

c. It does not exchange genetic information with other species.

(Reproductive isolation prevents gene flow between species.)

14. Which situation is not an example of a prezygotic barrier?

d. Two species of insects produce infertile offspring.

(This is postzygotic because it involves hybrid viability.)

15. Which term is used to describe the continued divergence of species based on the low fitness of hybrid offspring?

a. reinforcement

(Reinforcement increases reproductive isolation and divergence between species.)

16. Which components of speciation would be least likely to be a part of punctuated equilibrium?

c. ongoing gene flow among all individuals

(Punctuated equilibrium involves rapid changes, not continuous gene flow.)

17. If a person scatters a handful of garden pea plant seeds in one area, how would natural selection work in this situation?

Natural selection might favor plants with traits that help them survive in the specific environment (e.g., drought-resistant traits).

18. Why do scientists consider vestigial structures evidence for evolution?

Vestigial structures are remnants of traits that had a function in an ancestor but are no longer needed, showing evolutionary change.

19. How does the scientific meaning of “theory” differ from the common vernacular meaning?

In science, a theory is a well-supported explanation based on evidence, whereas, in everyday language, it’s just a guess or hypothesis.

20. Explain why the statement that a monkey is more evolved than a mouse is incorrect.

Evolution does not have a "goal" or direction. Monkeys and mice have evolved to be well-suited to their environments, not "more evolved."

21. Why do island chains provide ideal conditions for adaptive radiation to occur?

Isolated environments with varied habitats allow species to adapt to different ecological niches, leading to adaptive radiation.

22. Two species of fish had recently undergone sympatric speciation. The males of each species had a different coloring through which the females could identify and choose a partner from her own species. After some time, pollution made the lake so cloudy that it was hard for females to distinguish colors. What might take place in this situation?

Reproductive isolation may break down, leading to hybridization or fusion of the two species over time.

23. Why can polyploidy individuals lead to speciation fairly quickly?

Polyploidy can cause reproductive isolation because polyploid individuals can’t successfully mate with the original population, quickly forming a new species.

24. What do both rate of speciation models have in common?

Both models follow natural selection and involve changes in populations over time, either gradually or quickly.

25. Describe a situation where hybrid reproduction would cause two species to fuse into one.

If hybrids between two species have high fitness and can reproduce successfully, over time, gene flow could increase and the species might merge into one. This is fusion

Chapter Summary: Population Evolution & Genetics

19.1 Population Evolution

Modern Synthesis: Combines the work of Darwin, Wallace, and Mendel with population genetics. It explains the evolution of populations and species, from small-scale genetic changes to large-scale changes over geological time.

Tracking Evolution: Scientists track allele frequencies in populations over time. If allele frequencies change between generations, the population is evolving and is not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

19.2 Population Genetics

Phenotypic Variation: Variations in traits come from genetic and environmental factors. Only genetic differences are inherited and can be subject to natural selection.

Natural Selection: Favors alleles that provide beneficial traits and selects against deleterious traits.

Genetic Drift: Random changes in allele frequencies due to chance. Some individuals leave more offspring than others.

Gene Flow: When individuals join or leave a population, allele frequencies can change.

Mutations: New variations arise when mutations occur in an individual’s DNA, contributing to genetic diversity.

Non-random Mating: If individuals do not mate randomly, allele frequencies can change (e.g., assortative mating).

19.3 Adaptive Evolution

Adaptive Evolution: Natural selection leads to adaptive evolution by increasing the frequency of beneficial traits and reducing harmful traits.

Fitness: Natural selection favors individuals with higher fitness (better survival and reproduction).

Types of Selection:

Stabilizing Selection: Favors the average phenotype, reducing variation in the population.

Directional Selection: Shifts the population's traits toward one extreme (e.g., larger or smaller size) as environmental conditions change.

Diversifying (Disruptive) Selection: Favors two or more distinct phenotypes, increasing genetic variance.

Frequency-Dependent Selection: Selection favors common (positive frequency-dependent) or rare (negative frequency-dependent) traits.

Sexual Selection: Occurs when one sex has more variance in reproductive success. It can lead to sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females in traits like size, color, etc

Chapter Summary: Organizing Life on Earth & Phylogenetic Relationships

20.1 Organizing Life on Earth

Phylogeny: The evolutionary history of a group of organisms. Each organism shares relatedness with others, and scientists map these evolutionary pathways.

Taxonomy: Historically, organisms were classified in a taxonomic classification system. However, phylogenetic trees are now more commonly used to illustrate evolutionary relationships, showing how species are related over time.

20.2 Determining Evolutionary Relationships

Building Phylogenetic Trees: To build accurate phylogenetic trees, scientists collect data on morphological (form) and molecular (genetic) characteristics.

Homologous vs. Analogous Traits:

Homologies: Traits or genes that are similar due to shared evolutionary ancestry.

Analogies: Traits that appear similar but evolved independently due to similar environmental pressures.

Cladistics: A method used to organize evolutionary events and trace evolutionary relationships.

Maximum Parsimony: The principle that the simplest explanation, with the fewest evolutionary steps, is the most likely. In other words, the most likely evolutionary path is the one that requires the least divergence.

20.3 Perspectives on the Phylogenetic Tree

Phylogenetic Tree: The classic “tree of life” model shows how species are related. It is commonly used by scientists to represent evolutionary relationships.

Revised Models: New discoveries like Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) and genome fusion suggest that the model of evolution might need revision. Some scientists propose that the tree could be represented as a web or ring, indicating more complex evolutionary pathways.