social psychology; week 9; aggression

defining aggre ssion in social psychology

behaviour resulting in person injury or destruction of property (Bandura, 1973)

behaviour intended to harm another of the same species (Schere, Abeles & Fischer, 1975)

behaviour directed towards the goal of harming or injuring another living being who is motivated to avoid such treatment (Baron, 1977)

intentional infliction of harm on others (Baron & Byrne, 2000)

behaviour directed towards another carried out with the proximate intent to cause harm (Anderson & Bushman, 2002)

behaviour that is intended to harm others in some way (Baron & Branscombe, 2012)

Studying aggression

researchers measure aggression differently:

analogues of behaviour

bobo dolls (Bandura, Ross & Ross, 1963)

pressing a button to deliver a (fake) shock (Buss, 1961)

signals of intention

asking pp about situations and how willingly they’d be aggressive in those situations

expression of willingness to behave aggressively

ratings

self-report, report by others (teachers/ parents)

observation

indirect

non-physical, relational / psychological aggression

studying aggression - critical appraisal

analogues of behaviour

is this generalisable to real life settings?

signals of intention

intentions does not always translate to behaviour

ratings

social desirability bias

observation- interpret behaviour in line with prior expectations/ hypotheses

indirect

may inflate the prevalence of aggression if comparing to direct/ physical measures of aggression

Theoretical approaches

biological

psychodynamic

evolutionary

biosocial

frustration and aggression

excitation transfer

social

social learning theory

Biological approaches: psychodynamic

we have an unconscious drive known as ‘thanatos’ (death instinct)

over time this instinct builds up creating pressure which we cannot control and makes us do something aggressive

we deal with this tension by redirecting it to other activities = catharsis

how do you engage in catharsis?

Biological approaches: Evolutionary

aggressive behaviour is used to ensure genetic survival:

aggression thus must be linked to living long enough to procreate (can be seen when comparing against animal behaviour)

males fighting other males for mating rights, hunting for food, protecting territory or resources

mothers behave aggressively to protect their offspring

among humans → obtain social and economic advantage to improve survival rate of their children

critical evaluation of biological approaches

do appeal and resonate with the idea that violence is part of human nature

supported when comparing to animal behaviour

unknowable and immeasurable - instincts cannot be measures

supported by observational studies only, so cannot establish causality

evolutionary tendencies develop over thousands of years- difficult to measure in lab

humans behave aggressively outside of situations when we need to defend ourselves. children

aggression toward sour own relatives

biosocial approaches: frustration and aggression

based on the catharsis hypothesis

considers frustration as an antecedent to aggression

frustration = individual is prevented from achieving a goal by some external factor

aggression is a cathartic release of the build-up of frustration

cannot always challenge the direct source of aggression

sublimination- using aggression in acceptable activities such as sport

displacement- directing aggression onto something or someone else

Critical evaluation

provides useful opportunities for intervention to target

Marcus-Newhall et al (2000) meta-analysis of 49 studies of displaced aggression. Participants who were provoked but inable to retaliate directly against the source of frustration were significantly more likely to lash out at an innocent party unprovoked (displacement)

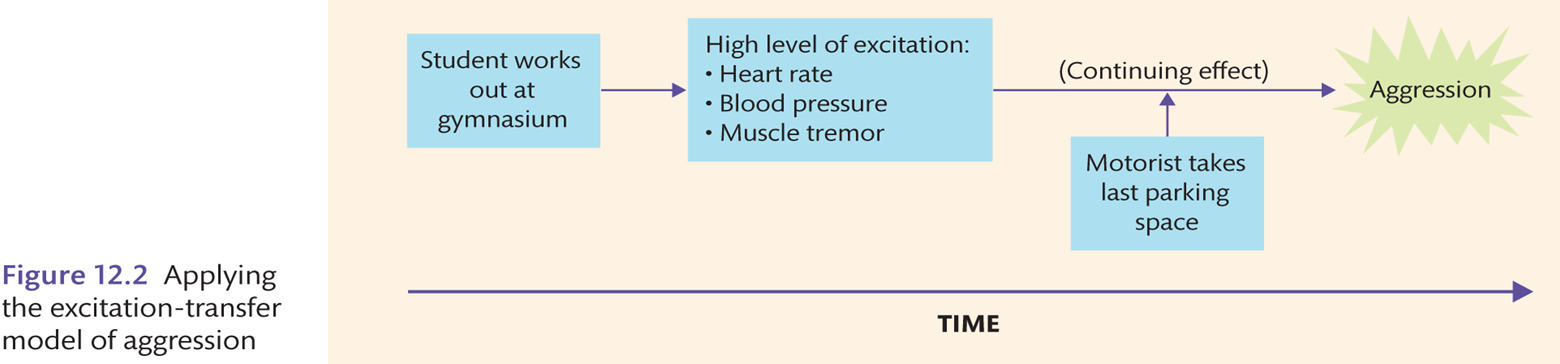

Biosocial approaches: excitation transfer

people experience physiological arousal in different contexts

arousal in one context can carry over to other situations and may increase likelihood of aggressive behaviour

requires three conditions:

1st stimuli produces arousal/ excitement

2nd stimuli occurs before the complete decay of arousal from the first stimulus

there is a misattribution of excitation to the 2nd stimulus

social approaches: social learning theory

aggression can be learnt

directly (operant conditioning)

e.g. child rewarded for an aggressive act will repeat the behaviour

indirectly (observation learning and vicarious reinforcement)

e.g. watching role models carry out aggressive behaviours and observing the consequence of the aggressive acts- whether the role model is rewarded or punished for them

if aggressive behaviour is rewarded, they learn it is socially acceptable

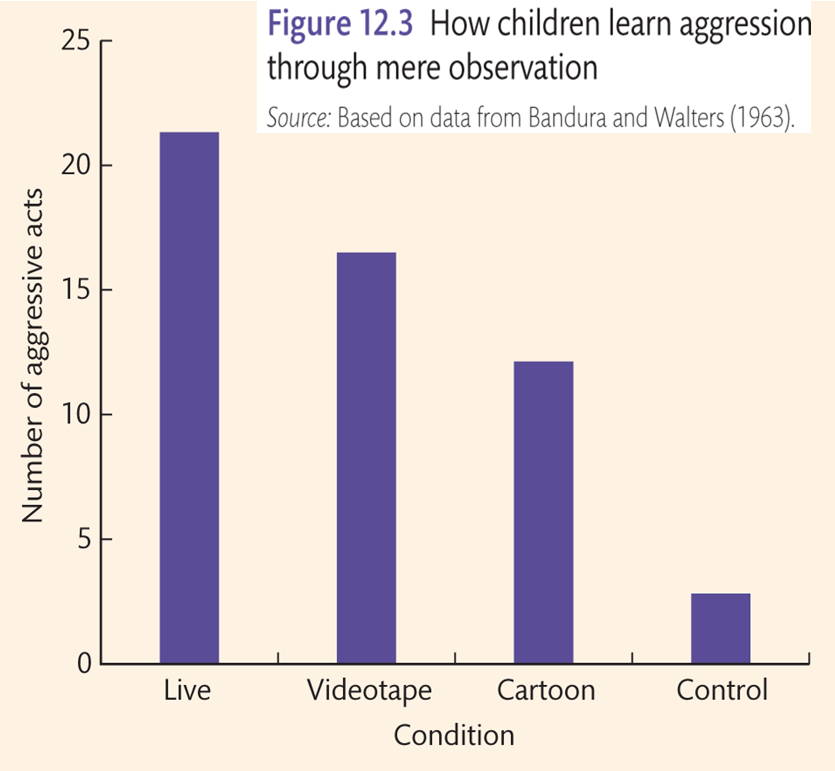

Study: Bandura and Walters (1963)

Nursery school children observe adult attack a ‘bobo doll’ when upset

in person

videotaped

cartoon

control- saw nothing

children exposed to an adult displaying aggressive behaviour demonstrated increase number of aggressive behaviours when alone

strongest effect for live observation

Critical evaluation

account for how children learn aggression form others around them, as well as through media

empirical support from many studies, but many are in labs

aggressive role model does not meant there is aggressive behaviour

does not include individual differences

effect of violent media on aggressive behaviour is not consistently replicated

Personal factors: sex and gender

may engage in aggressive behaviour more frequently than women (Eagly & Steffen, 1986)

but is this due to differences in hormones such as testosterone or differences in socialisation

there is individual variation in testosterone levels across genders, and testosterone only has a weak positive relationship with aggression (Book et al., 2001)

we learn gender appropriate behaviours (Eagly & Steffen, 1986)

physical aggression socially unacceptable for women

indirect (relational) forms of aggression may be more socially acceptable for women

this would predict that men and women would differ not in the amount but the type of aggressive behaviours displayed

Personal factors: gender

Denson et al., 2018

literature review of aggressive behaviour in women

overall, women are more likely to engage in indirect forms of aggressive behaviours

on lab studies: women are physically less aggressive compared to men

gender differences in aggression may be due to socialisation

Personal factors: personality

Barlett & Anderson, 2012:

big five personality traits and aggression

agreeableness:

negatively associated with aggression both directly and indirectly via aggressive attitudes and emotions

Neuroticism:

positive association with physical aggression both directly and indirectly via aggressive emotions

conclusions supported in a recent meta-analysis (Hyatt et al., 2019)

personal factors: attachment

attachment security (Ogivile et al., 2014)

meta-analysis of 30 studies that included an overall total of 2798 offenders, examines the relationship between attachment security and offending

offenders were less secure in their attachment than controls

insecure attachment was strongly associated with all types of criminality

BUT excluded studies involving juvenile and female offenders

attachment is also not always measured in the same way

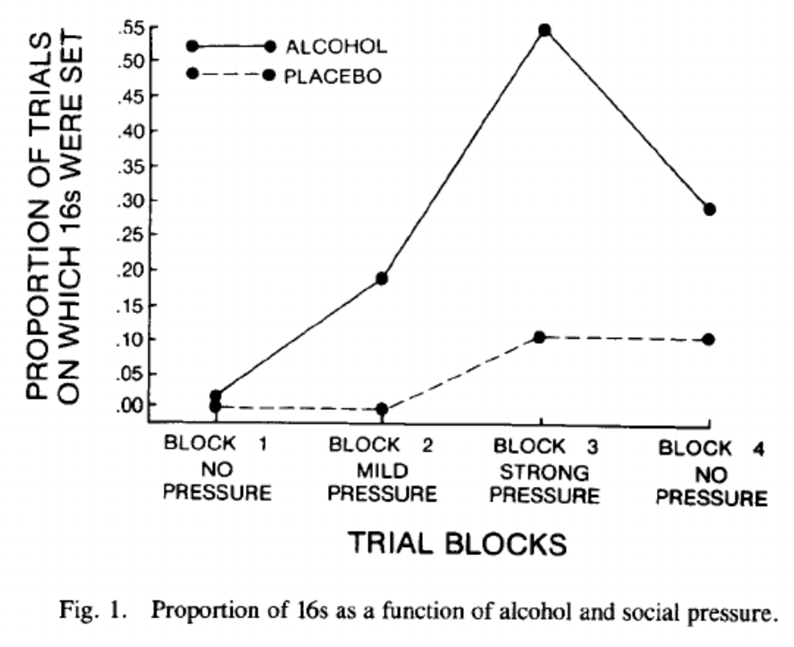

Situational factors: alcohol

alcohol present in 68% of incidents of physical aggression

Bushman & Cooper (1990) meta-analysis of experimental studies: alcohol consumptions increased aggressive behaviour in men

direct effects:

compromises cortical control and increases activity in more primitive brain areas- impairment in cognitive function, decision making

physiological arousal - in line with excitation transfer model

indirect effects:

placebo effect- expectations of receiving alcohol (in fact placebo) increased aggressive behaviour (Begue et al., 2009)

priming effect - activating thoughts of alcohol increased aggressive behaviour

Study: Taylor and Sears (1988)

assigned 18 male pps to alcohol vs placebo condition

Competitive task with another ppt involving reaction time

Loser received electric shock from opponent each time

Shock level “supposedly” set by the ppt delivering the shock (but actually kept constantly low by experimenter)

A confederate applied social pressure to the ppt, sometimes encouraging them to increase the shock level (max = level 16)

Those in the alcohol group were more susceptible to this pressure

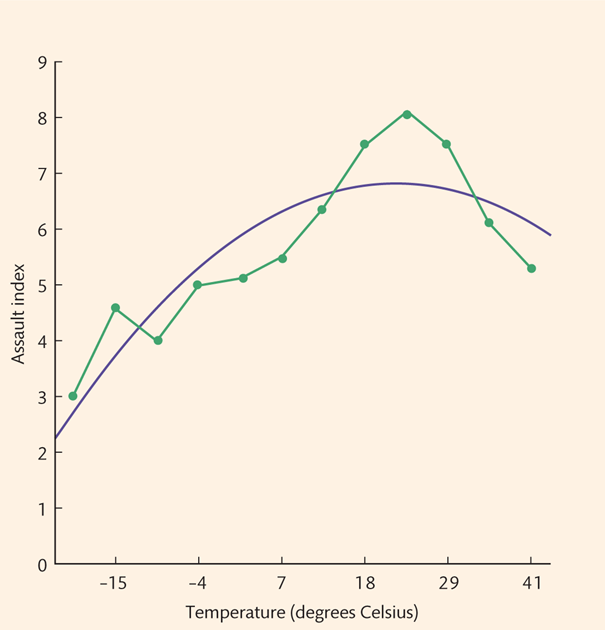

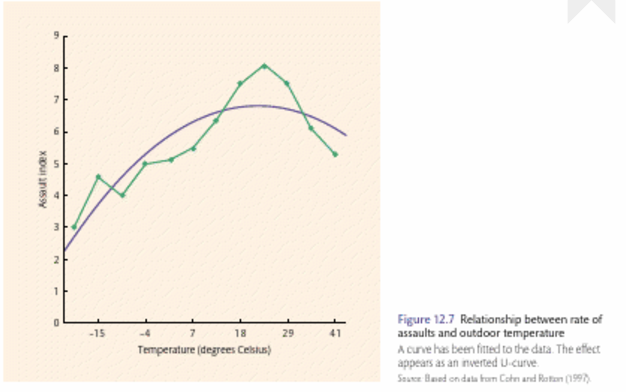

Situational factors: Heat

heat and aggression are linked - ‘hot-headed’, ‘blood boiling’

Cohn & Rotton (1997)

asssessed links between ambient temperature and assaults

increased ambient temperature is associated with increases in aggression

but the effect is not linear: it can be too hot to have the energy for aggression

effects stronger in the evening

potential interaction between heat and alcohol consumption

situational factors: crowding

population density linked to crime rates

increases stress, irritation, frustration and physiological arousal (Lawrence & Andrews, 2004)

anonymity in crowds

disinhibition- when the usual social forces that restrain us from acting anti-socially are reduced in some way

‘deindividuation’- feeling unidentifiable among many others means we think we are unlikely to face consequences

football hooliganism, riots, online bullying

Societal factors: disadvantaged groups

socially disadvantaged groups may engage in aggression if they believe

they are unjustly disadvantaged and they cannot improve their disadvantaged position

rates of homocide and non-lethal violence is higher among young, urban, poor and ethnic minority males- likely due to a mix of social and ecological factors

relative deprivation- discontent coupled with feeling that chances of improving conditions through legitimate means is minimal

vandalism, assault, burglary, riots or violent protests

social influences: violent media

Easy access to sanitised versions of aggression/ violence in the media has been argued to desensitise viewers

TV/film often depicts aggressors as unpunished heroes

Social learning theory argues that viewers will copy such reinforced acts, whereas the catharsis hypothesis argues it will release tension and reduce aggression

Black and Bevan (1992) viewing a violent film increases aggression scores compared to watching a non-violent film (priming effect)

Greitmeyer & Mugge 2014: Meta-analysis of 98 studies suggested that violent video games increase aggression

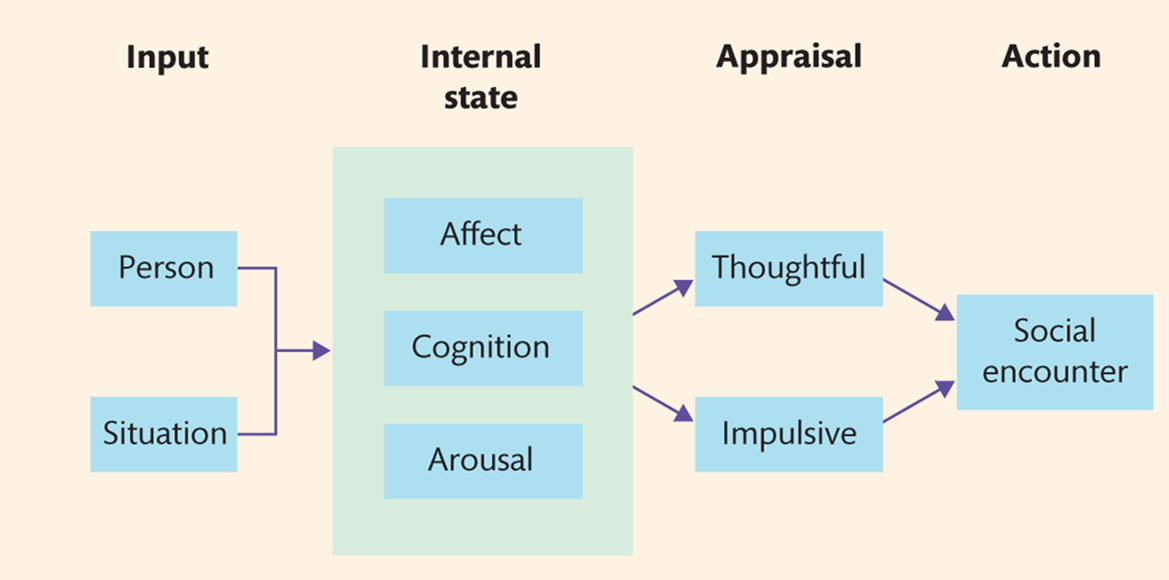

General Aggression Model (GAM)

Fundamental idea is the interplay between personal and situational variables

Which influence 3 internal states: cognition, affect, arousal

Affecting our appraisal/decision processes

Which influence aggressive outcomes

Applied in many contexts e.g. effect of media on violence (Anderson & Bushman, 2018), domestic violence (Warburton & Anderson, 2018),

Used to inform interventions to reduce aggression and violence

1. Person and situation factors increase or decrease the likelihood of aggression through their influence on internal state variables (i.e., cognition, affect, and arousal)

2. Person/situational variables can affect our moods/emotions, aggressive thoughts, and arousal which affect our appraisals and therefore alter the likelihood of aggression

3. Internal states influence appraisal of the situation. E.g. if a person is emotional, highly aroused, has aggressive thoughts , negative impulsive appraisals—including a goal, plan to harm the perpetrator—are more likely. The behavioural script that was activated during the appraisal is then enacted leading to the social encounter

Explaining temperature effects:

Measured hostile affect, hostile cognition, perceived arousal, and physiological arousal with 107 undergraduates who played video games while room temperature was controlled

Increasing temperature resulted in increased hostile affect, hostile cognition, and physiological arousal

Therefore, hot temperatures increase aggressive tendencies by 3 separate routes (internal states)

Excitation transfer processes may then increase the likelihood of biased (hostile) appraisals of ambiguous social events, resulting in increased likelihood of aggression

Institutionalised aggression

Institutions are places where there are strict rules that give little choice to members of that institution.

E.g. prisons, schools.

Institutional aggression refers to aggressive behaviours adopted by members of an institution; e.g. prisoners may form gangs that commit violence against other inmates/staff.

About 25% of prisoners are victimized by violence each year while 4–5% experience sexual violence and 1–2% are raped (Modvig, 2014)

Approximately 30% of all students annually experience some type of aggression at school (UNESCO, 2018)

Causes of institutionalised aggression

dispositional factors

•Personalities of the institution’s members – Importation model (Irwin and Cressey, 1962)

E.g. gender, personality, attachment, past experience

situational factors

Situation in which the members find themselves – Deprivation model (Sykes, 1958)

E.g. crowding, uncomfortable temperature, loss of freedom

linked to general aggression model and frustration-aggression hypothesis

Intimate partner violence

“any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” (WHO, 2002)

30% of women globally aged 15 and older have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence (Devries et al. 2013)

Female perpetrated IPV occurs more in societies that are modern, secular, and liberal (Archer, 2006)

likely reflecting changes in traditional gender roles/norms (societal influences)

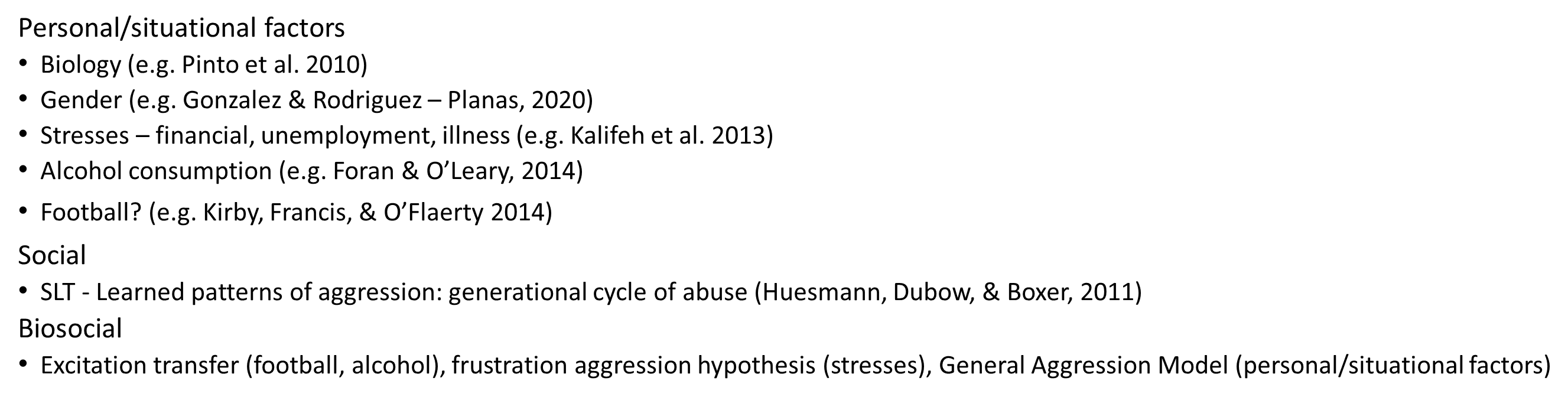

causes of IPV

Personal/situational factors

Biology (e.g. Pinto et al. 2010)

Gender (e.g. Gonzalez & Rodriguez – Planas, 2020)

Stresses – financial, unemployment, illness (e.g. Kalifeh et al. 2013)

Alcohol consumption (e.g. Foran & O’Leary, 2014)

Football? (e.g. Kirby, Francis, & O’Flaerty 2014)

Social

SLT - Learned patterns of aggression: generational cycle of abuse (Huesmann, Dubow, & Boxer, 2011)

Biosocial

Excitation transfer (football, alcohol), frustration aggression hypothesis (stresses), General Aggression Model (personal/situational factors)

Reading: chapter 12, pg 468-511

If aggression is omnipresent, is it an inescapable part of human nature?

Some scholars (e.g. Ardrey, 1961) claim that aggression is a basic human instinct, an innate fixed action pattern that we share with other species. If aggression has a genetic foundation, then presumably its expression is inevitable. Other scholars paint a less gloomy picture, arguing that even if aggressive tendencies are a part of our behavioural repertoire, it may be possible to control and possibly prevent the expression of the tendency as actual behaviour.

measuring aggression

scientists are likely to use definitions that correspond to their values thus the behaviours studies can differ from one researcher to the next

even though the chosen and agreed definition is not decided, researchers have developed operational definitions so they can manipulate and measure aggression in empirical research. However, different researchers have used different operationalisations, which include:

analogues of behaviour:

punching an inflated plastic doll (bandura, ross and ross)

pressing a button to deliver an electric shock to someone else (Russ)

signal of intention:

verbal expression of willingness to use violence in an experimental laboratory setting

Rating by self or others

written self-report by instituitionalised teenage boys about their prior aggressive behaviours

pencil-and-paper ratings by teachers and classmates of a child’s levle of aggressivenes

indirect aggression

relational aggression- damaging a person’s peer relationships or spreading rumours

Analogues

the first of these aggression measures is analoguesm which have been developed to enable researchers to conduct ethical research on aggression- it is difficult to justify an actual physical assault in an experimental setting

can we generalise findings from analogue measures of aggression to a larger population in real-life settings?

For example, what is the external validity of the aggression (electric shock) machine developed by Arnold Buss (1961), which is similar to the apparatus used by Stanley Milgram (1963) in his studies of obedience? In a test of this device, prisoners with histories of violence administered higher levels of shock to a confederate. Similarly, there is a parallel between the laboratory and real life regarding effects on aggression of alcohol, high temperatures, direct provocation and violence in the media.

Theoretical perspectives

Biological explanations

ethology

a branch of biology devoted to the study of instincts or fixed action patterns. among all members or a species when living in their natural environment

they stress the functional aspects of aggression, recognising the potential or instinct for aggression may be innate, whilst also noting that aggressive behaviour is elicited by specific stimuli in the environment; known as releasers

Lorenz invoked evolutionary principles to propose that aggression has survival value. An animal is considerably more aggressive towards other members of its species, which functions to distribute the individuals and/or family units in such a way as to make the most efficient use of available resources, such as sexual selection and mating, food and territory.

intraspecies aggression may not even result in actual violence, as one animal will display instinctual threat gestures that are recognised by the other animal, which can then depart the scene – ‘the Rottweiler growls so the Chihuahua runs’. Even if fighting does break out, it is unlikely to result in death, since the losing animal can display instinctual appeasement gestures that divert the victor from actually killing

Over time, in animals such as monkeys that live in colonies, appeasement gestures can help to establish dominance hierarchies or pecking orders. Thus, there is an innate urge to aggress, but its expression is conditional on appropriate stimulation by environmental releasers.

Lorenz (1966) extended the argument to humans, who he believed also inherited a fighting instinct . However, its survival value for humans is less clear than is the case for other animals. This is largely because humans lack well-developed killing appendages, such as large teeth or claws, so that clearly recognisable appeasement gestures seem not to have evolved

The implications of ethology

once we start being violent, we do not seem to know when to stop

in order to kill, we generally need to resort to weapons

Frustration-aggression hypothesis

It derived from the work of a group of psychologists at Yale University in the 1930s, and it has been used to explain prejudice. The anthropologist John Dollard and his psychologist colleagues proposed that aggression was always caused by some kind of frustrating event or situation; conversely, frustration invariably led to aggression. This reasoning has been applied to the effects of job loss on violence and the role of social and economic deprivation in ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the Kurds in Iraq and of non-Serbs in Bosnia. We might also speculate that terrorism is at least partly fuelled by chronic and acute frustration over the ineffectiveness of other mechanisms to achieve socio-economic and cultural goals – people are unlikely to become suicide bombers unless all other channels of goal achievement have proved ineffective. Frustration– aggression theory had considerable appeal, inasmuch as it was decidedly different from the Freudian approach. One major flaw is the theory’s loose definition of ‘frustration’ and the difficulty in predicting which kinds of frustrating circumstance may lead to aggression.

Imitation

Gabriel Tarde (1890), for example, devoted a whole book, Les lois de l’imitation , to the subject and boldly asserted that ‘Society is imitation’. What is unique in social learning theory is the proposition that the behaviour to be imitated must be seen to be rewarding in some way, and that some models, such as parents, siblings and peers, are more appropriate for the child than others. The learning sequence of aggression can be extended beyond direct interactions between people to include media images, such as on television. It can also explain how adults learn in later life. According to Bandura, whether a person is aggressive in a particular situation depends on:

a person’s previous experiences of others’ aggressive behaviour

how successful aggressive behaviour has been in the past

the current likelihood that an aggressive person will be either rewarded or punished

Bandura’s studies used a variety of experimental settings to show that children quite readily mimic the aggressive acts of others. Adults in particular make potent models, no doubt because children perceive their elders as responsible and authoritative figures. Early findings pointed to a clear modelling effect when the adult was seen acting aggressively in a live setting. Even more disturbingly, this capacity to behave aggressively was also found when children saw the adult model acting violently on television.

A theoretical approach: A blend of SLT with the learning of a particular kind of cognitive schema- the script

Children learn rules of conduct from those around them, so that aggression becomes internalised. A situation is recognised as frustrating or threatening: for example, a human target is identified, and a learnt routine of aggressive behaviour is enacted. Once established in childhood, an aggressive sequence is persistent. Research on age trends for murder and manslaughter in the United States shows that this form of aggression quickly peaks among 15to 25-year-olds and then declines systematically

What effect does spanking have on the social development of children?

From social learning theory, you might predict that children will learn that striking another is not punished, at least if the aggressor is more powerful! In a two-year longitudinal study of children and their parents, Murray Straus and his colleagues recorded how often a child was spanked (none to three or more times) each week. Across a two-year period, they found an almost linear relationship over time between the rate of spanking and the level of antisocial behaviour. What is more, children who were not spanked at all showed less antisocial behaviour after two years.

Another study, by Brian Boutwell and his colleagues, was able to disentangle environmental and genetic factors (Boutwell, Franklin, Barnes, & Beaver, 2011). Boutwell and colleagues’ data were drawn from a large-scale US longitudinal study of children born in 2001 that included twins (about 1,300 fraternal and 250 identical), which allows one to estimate a genetic impact on behaviour. The results pointed to a genetic susceptibility to long-term antisocial behaviour that was more marked in children who were spanked. This effect was negligible in girls.

Personality:

The tendency to aggress develops early in life and becomes a relatively stable behaviour pattern that can be linked to a tendency to attribute hostile intentions to others (Graham, Hudley, & Williams, 1992). Evaluation of people’s aggressiveness is an important part of some psychological tests and clinical assessments (Sundberg, 1977):

for example, in determining the likelihood of reoffending among violent offenders (Mullen, 1984). It is unlikely that some people are ‘naturally’ more aggressive than others; however, it is true that some of us can be more aggressive than others because of our age, gender, culture and life experiences. Violent offenders tend to have low self-esteem and poor frustration tolerance. However, narcissistic people who have inflated self-esteem and a sense of entitlement seem to be particularly prone to aggression (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998). Social workers often recognise children who have been exposed to above-average levels of violence, particularly in their homes, as being ‘high risk’ and in need of primary intervention.

A meta-analysis of 27 studies and 2,646 participants reveals that criminality is associated with having an insecure attachment style (Ogilvie, Newman, Todd, & Peck, 2014). Offenders were much more likely than non-offenders to have a childhood history of insecure attachment, and that this applied to all types of criminality.

Type A personality

Research has identified a behaviour pattern called Type A personality (Matthews, 1982). Type A people are overactive and excessively competitive in their encounters with others, and may be more aggressive towards those perceived to be competing with them on an important task (Carver & Glass, 1978). They are also prone to coronary heart disease. Type A people prefer to work alone rather than with others when they are under stress, probably to avoid exposure to incompetence in others and to feel in control of the situation. Type A behaviour can be socially destructive in a number of ways.

For example, Type A personalities have been reported to be more prone to abuse children and, in managerial roles in organisations, have been found to experience more conflict with peers and subordinates, but not their own supervisors (Baron, 1989).

hormones

Brian Gladue (1991) reported higher levels of overt aggression in males than in females. Moreover, this sex difference applied equally to heterosexual and homosexual males when compared with females – biology (male/female) rather than gender orientation was the main contributing variable.

In a second study, Gladue and his colleagues measured testosterone levels through saliva tests in their male participants and also assessed whether they were Type A or Type B personalities. The levels of shock administered to an opponent in an experimental setting were higher when the male was either higher in testosterone or a Type A personality, or both. Overall, there is a small correlation of 0.14 between elevated testosterone (in both males and females) and aggression – if it was causal, testosterone would explain 2% of variation in aggression. However, a correlation between levels of testosterone and aggression does not establish causality.

Causality could operate in the opposite direction. A more convincing link between the two was pinpointed by two studies in The Netherlands. Transsexuals who were treated with sex hormones as part of their gender reassignment showed increased or decreased proneness to aggression according to whether the direction of change was female to male or male to female. Although reviews of both animal and human studies confirm a link between testosterone and aggression, they also implicate other hormones – norepinephrine (noradrenaline), dopamine and serotonin The larger picture concerning the role of hormones is complex for several reasons: (a) studies vary in focusing on aggression induced by fear, stress and anger, as well as on instrumental aggression; (b) the hormones involved may be correlates of rather than causes of aggression; and (c) an environmental trigger is usually required to activate both a hormonal response and the expression of aggressive behaviour.

catharsis

An instrumental reason for aggression is catharsis. We aggress as an outlet or release for pent-up emotion – the cathartic hypothesis . Although associated with Freud, the idea can be traced back to Aristotle and ancient Greek tragedy: by acting out their emotions, people can purify their feelings. The idea has popular appeal. Perhaps ‘letting off steam’ from frustration can restore equanimity.

In Japan, some companies have already followed this principle, providing a special room with a toy replica of the boss upon which employees can relieve their tensions by ‘bashing the boss!’ (Middlebrook, 1980).

However, questions about the efficacy of the catharsis hypothesis have been around for many years, and more recent experimental research has gone further to outright reject the argument that cathartic behaviour can reduce subsequent aggression. Bushman, Baumeister and Stack (1999) found that those who hit a punching bag, believing that it reduced stress, were more likely later to punish someone who had transgressed against them.

Craig Anderson and his colleagues reported five experiments that demonstrated the effects of songs with violent lyrics on both aggressive feelings and thoughts. Students listened to rock songs that were either violent or nonviolent, and then rated pairs of words for their semantic similarity. The word meanings were either clearly aggressive (e.g. blood, butcher, choke, gun ) or ambiguously aggressive (e.g. alley, bottle, rock, stick ). The word pairs were aggressive– ambiguous, aggressive– aggressive, or ambiguous– ambiguous (the latter two pairings being controls).

Disinhibition, deindividuation and dehumanisation

Leon Mann (1981) explored deindividuation in a particular context relating to collective aggression , the ‘baiting crowd’. The typical situation involves a person threatening to jump from a high building, a crowd gathers below, and some begin to chant ‘jump, jump’. In one dramatic case in New York in 1938, thousands of people waited at ground level, some for eleven hours, until a man jumped to his death from a seventeenth-floor hotel ledge. Mann analysed twenty-one cases of suicides reported in newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s. He found that in ten out of the twenty-one cases where there had been a crowd watching, baiting had occurred. In comparing crowds that bait with those that do not, he found that baiting was more likely to occur at night and when the crowd was large (more than 300 people), and that the crowd was typically a long way from the victim, usually at ground level.

These conditions are likely to deindividuate people. The longer the crowd waited, the more likely they would bait, perhaps egged on by irritability and frustration. In a study in Israel, Naomi Struch and Shalom Schwartz (1989) investigated aggression among non-Orthodox Jews towards highly Orthodox Jews, measured in terms of strong opposition to Orthodox institutions. They found two contributing factors: a perception of intergroup conflict of interests, and a tendency to regard Orthodox Jews as ‘inhuman’.

Situational variables: crowding

Crowding that leads to fighting has long been recognised in a variety of animal species (e.g. Calhoun, 1962). For humans, crowding is a subjective state and is characterised by feeling that one’s personal space has been encroached. There is a distinction between invasion of personal space and a high level of population density but in practical terms there is also an overlap. Urbanisation acquires more people to share a limited amount of space, with elevated stress and potentially antisocial consequences

In a study conducted in Toronto, Wendy Regoeczi (2003) noted that population density as a gross measure can contribute to the overall level of crime in an area. However, variables crucial to a state of crowding are more finely grained – household density (persons per house) and neighbourhood density (detached housing versus high-rise housing). Her results showed that density on both measures correlated positively with self-reported feelings of aggression and also of withdrawal from interacting with strangers

In a prison context, Claire Lawrence and Kathryn Andrew (2004) confirmed a consistent finding in studies of the penal environment. Feeling crowded made it more likely that events in a UK prison were perceived as aggressive and the protagonists as more hostile and malevolent. In an acute psychiatric unit in New Zealand, Bradley Ng and his colleagues found that ‘crowding’ (inferred from higher ward occupancy rates) was associated with a higher number of violent incidents and increased verbal aggression

situational variables- sports events

Sports events can be associated with spectator violence. Since the early 1970s, European, but particularly English, football has become strongly associated with hooliganism – to such an extent, for example, that the violence of some English fans in Belgium associated with Euro 2000 undoubtedly contributed to England’s failure to be chosen to host the World Cup in 2006. England was made to wait a little longer! Popular hysteria has characterised ‘soccer hooliganism’ in terms of the stereotyped images of football fans on the rampage

sports riots aren’t just a part of European sports and has been recorded in 6 continents.

It is tempting to explain spectator violence purely in terms of deindividuation in a crowd setting, but a study of football hooliganism by Peter Marsh and his colleagues suggested another contributing cause. Violence by fans is often orchestrated far away from the stadium and long before a given match. What might appear to be a motley crowd of supporters on match day can actually comprise several groups of fans with differing status. By participating in ritualised aggression over a period of time, a faithful follower can be ‘promoted’ into a higher-status group and can continue to pursue a ‘career structure’. Rival fans who follow their group’s rules carefully can avoid real physical harm to themselves or others. Organised football hooliganism is a kind of staged production rather than an uncontrollable mob

Football hooliganism can also be understood in more societal terms. For example, Patrick Murphy and his colleagues described how football arose in Britain as a working-class sport. By the 1950s, a working-class value of masculine aggression was associated with the game. Attempts by a government (seen as middle class) to control this aspect of the sport would enhance class solidarity and encourage increased violence that generalises beyond matches (Murphy, Williams, & Dunning, 1990). This account is societal and involves intergroup relations and the subcultural legitimation of aggression. Finally, hooliganism can be viewed in intergroup terms: in particular, the way hooligans behave towards the police and vice versa

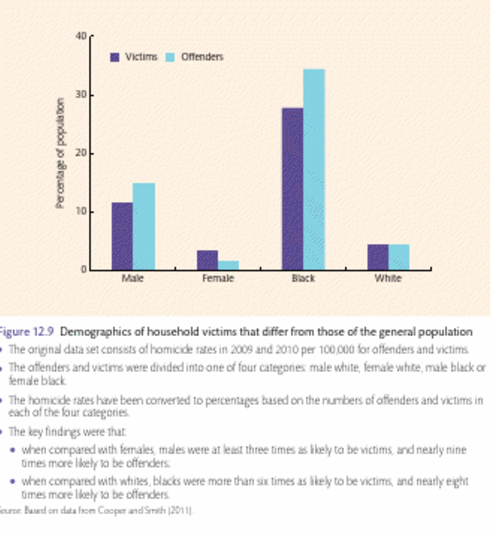

criminality and demographics

Stereotypes based on gender most often depict men as being more aggressive than women. It is possible that as gender roles in Western societies are re-orientated, women’s inhibitions against violence will diminish – emancipation may be criminogenic. The redefinition of male and female roles (also see Chapter 14) in most Western societies in recent decades is correlated with a rise in alcohol and drug abuse among women. The return of women to the workforce has coincided with widespread unemployment, a further trigger for increased offences against persons (and property). Although criminal violence is still more prevalent among men than women, the rate of violent offending, in particular murder, has increased more rapidly among women. We include race (or ethnicity) because of accumulating relevant data (see Figure 12.9 for an American study by Cooper and Smith (2011), who included both offenders and victims in their analyses).

Some societies or groups in society subscribe to a culture of honour that places a unique emphasis on upholding and defending the reputation and person of oneself and one’s family; in particular, it is of utmost importance for men to maintain reputations for being competent providers and strong protectors. In such cultures men are particularly prone to detecting personal slights, insults and threats and to reacting aggressively to them. Osterman and Brown (2011) even found that violence towards self, in the form of suicide, was elevated, particularly among rural whites, in US states characterised by a culture of honour. Joseph Vandello, Dov Cohen and their colleagues have extensively studied the impact of a culture of honour on domestic violence. Regions that place a value on violence to restore honour include some Mediterranean countries, the Middle East and Arab countries, Central and South America, and the southern United States. This research, comparing Brazilian and US honour culture participants with northern US participants, and comparing peoples in the Americas generally, reached three conclusions:

female infidelity damages a man’s reputation, particularly in honour cultures

a man’s reputation can be partly restored by exacting retribution

cultural values of female loyalty and sacrifice on one hand and male honour on the other, validate about is a relationship. The same values reward a woman who ‘soldiers on’ in the face of violence

Attitudes towards honour killings of women who had ‘dishonoured’ their family in Amman, Jordan, were the focus of a large-scale study by criminologists Manuel Eisner and Lana Ghuneim (2013). They found that adolescents whose world views were collectivist and patriarchal were more accepting of honour killings. Among both males and females, approval of honour killings was stronger among adolescents from poorer and less-educated families with a traditional background, and who showed moral disengagement that inured them to violence. In addition, approval was strongest among males who had a history of harsh paternal discipline and placed a premium on a norm of female chastity. Eisner and Ghuneim (2013) were disappointed that: ‘Within a country that is considered to be modern by Middle Eastern standards this represents a high proportion of young people who have at least some supportive attitudes to honor killing’ (p. 413). Outside honour cultures, aggression against women is generally not a matter to display publicly. In patriarchal cultures, men and boys are proud of male-directed violence but ashamed of femaledirected aggression (Hilton, Harris, & Rice, 2000). Interpersonal violence occurs in most societies, but some societies actively practise a lifestyle of non-aggression. There may be as many as twenty-five societies with a world view based on cooperation rather than competition (Bonta, 1997). Such communities are Culture of honour A culture that endorses male violence as a way of addressing threats to social reputation or economic position.

subcultures of violence:

Many societies include minority subgroups in which violence is legitimised as a lifestyle – they represent a subculture of violence (Toch, 1969). The norms of such groups reflect an approval of aggression, and there are both rewards for violence and sanctions for non-compliance. In urban settings, these groups are often labelled and self-styled as gangs, and the importance of violence is reflected in their appearance and behaviour (Alleyne & Wood, 2010). In his book Political Violence: The Behavioral Process, Harold Nieburg (1969) painted a graphic picture of the traditional initiation rite for the Sicilian Mafia. After a long lead-up period of observation, the new Mafia member would attend a candlelit meeting of other members and be led to a table showing the image of a saint, an emblem of high religious significance. Blood taken from his right hand would be sprinkled on the saint, and he would swear an oath of allegiance binding him to the brotherhood. In a short time, he would then prove himself worthy by executing a suitable person selected by the Mafia

Subculture of violence- machismo

prove himself worthy by executing a suitable person selected by the Mafia. Machismo plays a key role in encouraging a subculture of violence among boys and young men. This is evident in Latin American families (Ingoldsby, 1991). It is also evident in another Latin culture, Italy, where aggression is encouraged in adolescent boys from traditional villages in the belief that it shows sexual prowess and shapes a dominant male in the household (Tomada & Schneider, 1997). One consequence of this is that there is more male bullying in Italian schools than in England, Spain, Norway or Japan

A cognitive analysis

Neo-associationist analysis- includes the idea that merely thinking about an act can faciltiate its performance. Real or fictional images of violence that are presented to an audience can translate later in antisocial acts.

Berkowitz argued that memory can be viewed as a collection of networks, each consisting of nodes. A node can include substantive elements of thoughts and feelings, connected through associative pathways. When a thought comes into focus, its activation radiates out from that particular node via the associative pathways to other nodes, which in turn can lead to a priming effect. Consequently, if you have been watching a movie depicting a violent gang ‘rumble’, other semantically related thoughts can be primed, such as punching, kicking and shooting a gun . This process can be mostly automatic, without much conscious thinking involved. Similarly, feelings associated with aggression, such as some components of the emotion of anger, or of other related emotions may likewise be activated. The outcome is an overall increase in the probability that an aggressive act will follow. Such action could be of a generalised nature, or it may be similar to what was specifically portrayed in the media – in which case, it could be a ‘copy-cat crime’

Weapons effect

The weapons effect is a phenomenon that can be accounted for by a neo-associationist approach. Berkowitz asked the question, ‘Does the finger pull the trigger or the trigger pull the finger?’ (Berkowitz & LePage, 1967). If weapons suggest aggressive images not associated with most other stimuli, a person’s range of attention is curtailed. In a priming experiment by Craig Anderson and his colleagues, participants first viewed either pictures of guns or scenes of nature (Anderson, Anderson, & Deuser, 1996). They were then presented with words printed in different colours that had either aggressive or neutral connotations. Their task was to report the colours of the words. Their response speed was slowest in the condition where pictures of weapons preceded aggressive words. We should not infer from this that weapons always invite violent associations. A gun, for example, might be associated with sport rather than being a destructive weapon (Berkowitz, 1993) – hence the more specific term ‘weapons effect’. However, there is overwhelming evidence that availability or ownership of guns is significantly correlated with a country’s suicide and homicide rates (Stroebe, 2014). Huesmann and his colleagues argue that long-term adverse effects of exposure to media violence are likely based on extensive observational learning in the case of children, accompanied by the acquisition of aggressive scripts , whereas short-term effects among adults and children are more likely based on priming. For example, Sarah Coyne and her colleagues used a priming technique to study female college students’ responses to three kinds of content in video scenes: physical aggression, relational aggression or no aggression. The content of both physical aggression and relational

aggression primed later aggressive thoughts, making them more accessible in memory.

Rape myths

Philipp Sussenbach and his colleagues give examples of beliefs that typify rape myth acceptance (RMA): ‘A lot of women lead a man on and then they cry rape’ and ‘Many women secretly desire to be raped’. Here are some of their findings based on an RMA scale: ● ● ● In a correlational study of German residents (Sussenbach & Bohner, 2011), those who scored high on RMA also scored high on Right Wing Authoritarianism (see Chapter 10 ). In an experimental study of eye movement responses to a supposed police photograph of a rape scene (Sussenbach, Bohner, & Eyssel, 2012), participants who scored high on RMA more quickly attended to rape-consistent cues, i.e. two wine glasses and a bottle. In an experimental study using a mock jury, high RMA scorers were more lenient in sentencing when irrelevant rape myth-consistent information to the case was presented. This suggested that rape myth acceptance is a cognitive schema that acts as a bias towards blaming the victim, even when there is lack of certainty about the facts

Erotica and aggression

Research indicates that any effect of erotica on aggression depends on the kind of erotica viewed.

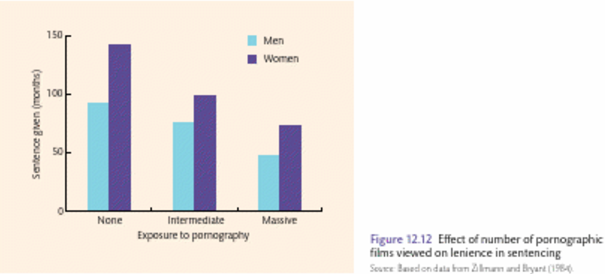

For example, viewing pictures of attractive nudes (mild erotica) has a distracting effect (such pictures reduce aggression when compared with neutral pictures) (Baron, 1979; Ramirez, Bryant, & Zillmann, 1983), whereas viewing images of explicit lovemaking (highly erotic) can increase aggression. Sexually arousing non-violent erotica could lead to aggression because of excitation-transfer. However, excitation-transfer includes the experience of a later frustrating event, which acts as a trigger to aggress. In short, there has not been a convincing demonstration of a direct link between erotica per se and aggression. In a more dramatic demonstration, Zillmann and Bryant (1984) exposed participants to a massive amount of violent pornography and then had them actively irritated by a confederate. Participants became more callous about what they had seen: they viewed rape more tolerantly and became more lenient about prison sentences that they would recommend.

However, the experimental design involves a later provoking event, so this outcome could be an instance of excitation transfer. Schema Cognitive structure that represents knowledge about a concept or type of stimulus, including its attributes and the relations among those attributes.

association between pornography and sexual offending

Michael Seto and his colleagues suggest that people who are already predisposed to sexually offend are the most likely to be affected by pornography exposure as well as to show the strongest consequences.

When violence is mixed with sex in films, there is, at the very least, evidence of male desensitisation to aggression against women – callous and demeaning attitudes. A meta-analysis by Paik and Comstock (1994) found that sexually violent TV programmes were linked to later aggression, and this was most clearly evident in male aggression against women. Daniel Linz and his colleagues reported that when women were depicted enjoying violent pornography, men were later more willing to aggress against women – although, interestingly, not against men. Perhaps just as telling are other consequences of such material: it can perpetuate the myth that women actually enjoy sexual violence. It has been demonstrated that portrayals of women apparently enjoying such acts reinforce rape myths and weaken social and cognitive restraints against violence towards women. Zillmann and Bryant (1984) pointed out that the cumulative effect of exposure to violent pornography trivialises rape by portraying women as ‘hyperpromiscuous and socially irresponsible’.

A feminist perspective emphasises two concerns about continual exposure of men to media depicting violence and/or sexually explicit material involving women

exposure to violence will cause men to become callous or desensitised to violence against female victims

exposure to pornography will contribute to the development of negative attitudes towards women

Objection theory

women’s life experiences and gender socialisation routinely include experiences of sexual objectification

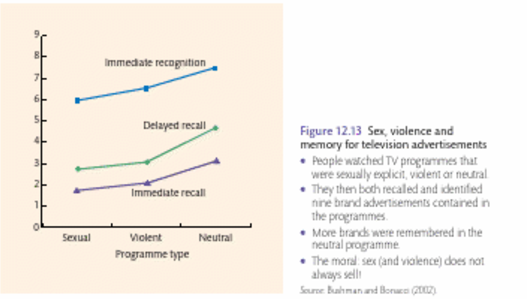

Brad Bushman and Angelica Bonacci (2002) studied more than 300 young to middleaged people who watched one of three television programmes, each containing nine brand advertisements. The programme themes were sexually explicit, violent or neutral. Later, the participants tried to recall the brands and to identify them from photographs.

The sex difference in intimate partner violence arises for a number of reasons

evolutionary perspective: human fear is an adaptive human emotional response to threat that reduces exposure to physical danger. For females, there is a higher level of fear in the face of direct aggression

biological perspective: oxytocin is a hormone that regulates several reproductive and maternal behaviours, including child birth. When released in responding to danger, it mediates the reduction of stress associated with fear

intimate partner violence: the release of oxytocin is more pronounced in the presence of an intimate partner. If threat is involved, the higher level of oxytocin associated with the partner reduces the stress experiences and increases the likelihood of female aggression

cultural norms: women in western culture often equal or exceed men in their level of aggression. Norms that govern the expression of aggression vary across cultures and provide another causal path for sex differences in aggression to emerge.

Gender asymmetry

Richard Harris and Cynthia Cook (1994) investigated students’ responses to three scenarios: a husband battering his wife, a wife battering her husband and a gay man battering his male partner, each in response to verbal provocation. The first scenario, a husband battering his wife, was rated as more violent than the other two scenarios. Further, ‘victim blaming’ – an example of belief in a just world – was attributed most often to a gay victim, who was also judged most likely to leave the relationship. It seems that the one act takes on a different meaning according to the gender of the aggressor and the victim.

DcKeseredy (2006) and Claire Renzetti (2006) agree in deciding that both gender and ethnic asymmetries underlie partner abuse:

most sexual assaults in heterosexual relationships are committed by men

much of women’s use of violence is in self-defence against their partners assault

men and women in different ethnic groups ‘do gender’ differently, including variations in perceptions of when it is appropriate to use violence

what factors influence why people hurt those closest to them?

Learnt patterns of aggression: imitated from parents and significant others, together with low competence in responding non-aggressively; there is a generational cycle of child abuse (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980), and the chronic repetition of violence in some families has been identified as an abuse syndrome

The proximity of family members, which makes them more likely to be sources of annoyance or frustration, and targets when these feelings are generated externally;

Stresses , especially financial difficulties, unemployment and illnesses (including postnatal depression; see Searle, 1987); this partly accounts for domestic violence being much more common in poorer families;

The division of power in traditional nuclear families, favouring the man, which makes it easier for less democratic styles of interaction to predominate (Claes & Rosenthal, 1990);

High alcohol consumption, which is a common correlate of male abuse of a spouse

Reducing aggression

Hong and Espelage (2012) reviewed studies and meta-analyses of research on school bullying and peer victimisation, to conclude that the impact of anti-bullying programs has been low, and that punitive tactics (e.g. corporal punishment and suspension) have proved ineffective. They suggest that a more effective approach would be multipronged. This would involve modifying the behaviour of both bullies and their victims and of non-involved bystanders, addressing classroom and school climate, and reaching out to the family, community, and wider society.

Regarding attitudes towards women that promote aggression, there are direct educational opportunities that can be used. For example, media studies courses can help develop critical skills that evaluate whether and how women are demeaned, and in what way we might undermine rape myths

Laws can also play a role in reducing aggression or its effects. Take gun ownership laws in the United States as an example. You now know something of the weapons effect. Consider this irony: guns and ammunition may be kept in the home to confer protection. The same guns are overwhelmingly used to kill a family member or an intimate acquaintance, particularly in homes with a history of drug use and physical violence

Mass violence such as genocide and war is a different matter. There is room for the introduction of peace studies into the formal education system. Peace education is more than an anti-war campaign: it has broadened to cover all aspects of peaceful relationships and coexistence. By teaching young children how to build and maintain self-esteem without being aggressive, it is hoped that there will be a long-term impact that will expand into all areas of people’s lives