LO Answers

Structure and Function (S&F)

Introduce/discuss different types of bone healing

Primary intention - Primary intention (also called primary bone healing) occurs when the bone ends are closely aligned and stabilized, such as after surgical fixation (e.g., with plates and screws). It involves minimal to no callus formation, as the bone heals through direct remodelling.

In primary bone healing, osteoclasts resorb old bone, and osteoblasts follow to deposit new bone. This process occurs through "cutting cones," where small tunnels are made through the bone, allowing direct deposition of new bone.

Secondary intention - Secondary intention (secondary bone healing) happens when the bone fragments are not perfectly aligned, and there is a small gap between them. It is the more common type of bone healing in fractures treated conservatively without surgical intervention.

This process involves several stages:

Inflammation: Haematoma forms at the fracture site, attracting inflammatory cells.

Soft Callus Formation: Cartilage forms, bridging the fracture gap.

Hard Callus Formation: The cartilage is replaced by woven bone.

Remodelling: The woven bone is eventually replaced by stronger lamellar bone over time.

Introduce the four stages of healing

1. Hematoma Formation (Inflammatory Phase)

Timeframe: First few hours to days after the fracture.

Description: When a bone fractures, blood vessels in the bone and surrounding tissues are damaged, leading to a hematoma (blood clot) at the fracture site. This clot forms the initial scaffold for healing and releases inflammatory signals, attracting immune cells, fibroblasts, and other healing factors.

Purpose: The inflammatory cells help to clean up debris, and blood clotting begins the repair process.

2. Fibrocartilaginous Callus Formation (Soft Callus Phase)

Timeframe: Begins within the first few days and lasts about 2 to 3 weeks.

Description: Cells called chondroblasts (cartilage-forming cells) and fibroblasts infiltrate the fracture site, and the hematoma is replaced by a soft fibrocartilaginous callus. This soft callus bridges the gap between the broken bone ends but is still weak and cannot support weight.

Revascularisation also occurs where new blood vessels begin to grow into the area, restoring blood supply to the damaged bone tissue, which is essential for the delivery of oxygen, nutrients and healing factors.

Purpose: Acts as a temporary structure to hold the bone together, stabilizing the fracture.

3. Bony Callus Formation (Hard Callus Phase)

Timeframe: Begins around 2 to 3 weeks after the fracture and can last for several months.

Description: Osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) begin to replace the soft callus with a hard bony callus made of woven bone. This woven bone is less organized and weaker than normal bone but provides more stability to the fracture site.

Purpose: Strengthens the fractured area with bone tissue, preparing for further remodelling.

4. Bone Remodelling

Timeframe: Starts around 3 to 4 weeks after the injury and can last months to years.

Description: The woven bone is gradually replaced by more organized, strong lamellar bone. Osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells) break down the woven bone, and osteoblasts rebuild it as stronger lamellar bone. The bone is restored to its original shape, structure, and strength through this remodelling process.

Purpose: Final stage where the bone regains its normal strength and shape, adapting to the mechanical stress placed on it.

Revascularisation - Revascularization is crucial to nourish the healing tissue, while the soft callus acts as a temporary bridge between the bone fragments.

This involves the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and the repair of damaged ones, ensuring that the healing tissue receives adequate oxygen, nutrients, and immune cells necessary for recovery and regeneration. In bone healing, effective revascularization is critical as it supports the survival and function of osteogenic cells (cells responsible for bone formation) and the removal of waste products, facilitating proper and efficient bone repair.

Difference between trauma induced and surgery induced

Trauma-Induced Bone Healing

Cause: Results from accidental injuries such as falls, sports injuries, or car accidents.

Healing Environment: Often involves irregular, displaced fractures with varying degrees of soft tissue damage.

Healing Process: Typically follows secondary intention, characterized by more significant callus formation as the body naturally stabilizes and repairs the fracture without surgical intervention.

Challenges: Healing can be complicated by factors like infection, poor alignment, and extensive soft tissue damage.

Surgery-Induced Bone Healing

Cause: Results from planned surgical procedures such as osteotomies, dental implants, or fracture fixation.

Healing Environment: Controlled and optimized conditions with precise alignment and stabilization of bone segments using surgical tools and implants.

Healing Process: Often follows primary intention, with minimal callus formation due to direct bone healing and rigid stabilization provided by surgical fixation devices.

Advantages: Reduced healing time and complications due to the controlled environment and precise alignment achieved through surgery.

Revisit/outline pain pathways

Peripheral Pathway:

Nociceptors Activation: Nociceptors in dental tissues (e.g., dentin, pulp) detect noxious stimuli.

Afferent Nerve Fibers: Pain signals are transmitted through the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), specifically via its branches (ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular).

Central Pathway:

Spinal Trigeminal Nucleus: Pain signals from the trigeminal nerve synapse in the spinal trigeminal nucleus located in the brainstem.

Ascending Pathways: Second-order neurons cross to the opposite side of the brainstem and ascend to the thalamus via the trigeminothalamic tract.

Thalamus to Cortex: Third-order neurons project from the thalamus to the somatosensory cortex, where pain is consciously perceived and processed.

Descending Modulation:

Brainstem Modulation: Descending pathways from the brainstem (e.g., periaqueductal grey, raphe nuclei) release inhibitory neurotransmitters (endorphins, serotonin, norepinephrine) to modulate pain at the spinal cord level.

Local Anaesthetics: In dental practice, local anaesthetics (e.g., lidocaine) are often used to block the peripheral transmission of pain signals by inhibiting sodium channels in nerve fibres.

ABPIP

Anatomy (including dental anatomy)

Composition of blood

Plasma: ~55%

Red Blood Cells: ~45% (of which, about 99% of formed elements)

White Blood Cells and Platelets: Less than 1% (of which, white blood cells are about 1% of formed elements)

Biochemistry

Clotting factors

1. Factor I: Fibrinogen

Function: Fibrinogen is converted to fibrin, which forms the mesh that stabilizes the blood clot. Fibrin is the final structural component of the clot.

2. Factor II: Prothrombin

Function: Prothrombin is converted to thrombin, a key enzyme that converts fibrinogen into fibrin and activates several other clotting factors (e.g., Factor V, Factor VIII, and Factor XIII).

3. Factor III: Tissue Factor (TF) or Thromboplastin

Function: Tissue factor is a transmembrane protein that initiates the extrinsic pathway of coagulation by binding to and activating Factor VII.

4. Factor IV: Calcium ions (Ca²⁺)

Function: Calcium is a cofactor required for various steps of the coagulation cascade, including the activation of Factor IX, Factor X, and the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin.

5. Factor V: Proaccelerin or Labile Factor

Function: Factor V works as a cofactor for Factor Xa in the prothrombinase complex, which converts prothrombin to thrombin.

6. Factor VII: Proconvertin or Stable Factor

Function: Factor VII, when bound to tissue factor (Factor III), activates Factor X in the extrinsic pathway. It also contributes to the activation of Factor IX.

7. Factor VIII: Anti-haemophilic Factor A

Function: Factor VIII works as a cofactor for Factor IX in the tenase complex, which activates Factor X in the intrinsic pathway.

8. Factor IX: Christmas Factor or Anti-haemophilic Factor B

Function: Factor IX is activated by Factor XIa or by the Factor VIIa-Tissue Factor complex. It, along with Factor VIII, activates Factor X in the intrinsic pathway.

9. Factor X: Stuart-Prower Factor

Function: Factor X is a key enzyme in the common pathway. Once activated, it forms the prothrombinase complex with Factor V, which converts prothrombin to thrombin.

10. Factor XI: Plasma Thromboplastin Antecedent (PTA)

Function: Factor XI is part of the intrinsic pathway and is activated by Factor XIIa. It, in turn, activates Factor IX.

11. Factor XII: Hageman Factor

Function: Factor XII initiates the intrinsic pathway by activating Factor XI. It also plays a role in fibrinolysis (clot breakdown) and inflammation.

12. Factor XIII: Fibrin-Stabilizing Factor

Function: Factor XIII is activated by thrombin and cross-links fibrin molecules to stabilize the fibrin mesh, strengthening the blood clot.

Additional Components:

Prekallikrein: Works with Factor XII in the intrinsic pathway and also plays a role in inflammation and fibrinolysis.

High-Molecular-Weight Kininogen (HMWK): Acts as a cofactor with Factor XII and prekallikrein, participating in the intrinsic pathway and inflammation.

Clotting cascade

The coagulation cascade is a complex series of biochemical events that lead to blood clotting and the formation of a stable blood clot to prevent excessive bleeding after injury. It involves a sequence of enzymatic reactions and the activation of clotting factors. The cascade is divided into three main pathways:

1. Intrinsic Pathway

Trigger: Activated by damage to the blood vessel or exposure of blood to collagen and other subendothelial substances.

Process:

Factor XII is activated to Factor XIIa.

Factor XI is activated to Factor XIa.

Factor IX is activated to Factor IXa.

Factor IXa forms a complex with Factor VIIIa and calcium ions, leading to the activation of Factor X to Factor Xa.

Role: Amplifies the clotting process and is responsible for most of the thrombin generation in vivo.

2. Extrinsic Pathway

Trigger: Initiated by external trauma or injury that exposes tissue factor (TF) from damaged tissues.

Process:

Tissue Factor (TF) binds with Factor VII to form the TF-VIIa complex.

This complex activates Factor X to Factor Xa.

Role: Provides a rapid response to blood vessel injury and initiates clotting.

3. Common Pathway

Process:

Factor Xa combines with Factor Va (prothrombinase complex) and calcium ions to convert Prothrombin (Factor II) into Thrombin (Factor IIa).

Thrombin then converts Fibrinogen (Factor I) into Fibrin.

Fibrin strands form a mesh that stabilizes the clot.

Thrombin also activates Factor XIII to Factor XIIIa, which cross-links the fibrin strands to stabilize and strengthen the clot.

Regulation and Fibrinolysis

Regulation: To prevent excessive clotting, the cascade is regulated by various inhibitors like antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S.

Fibrinolysis: After healing, the clot is removed by fibrinolysis, where plasminogen is activated to plasmin, which digests fibrin and dissolves the clot.

Physiology

Platelet plug

Vascular Injury:

When a blood vessel is injured, the underlying collagen and other subendothelial structures are exposed to the blood flow.

Platelet Adhesion:

Platelet Activation: Platelets in the bloodstream adhere to the exposed collagen and other matrix proteins at the site of injury. This adhesion is facilitated by von Willebrand factor (vWF), which acts as a bridge between platelets and collagen.

Platelet Receptors: Platelets have receptors (e.g., GPIa/IIa and GPIb/IX/V) that bind to these matrix proteins.

Platelet Activation:

Release Reaction: Upon adhesion, platelets become activated and release various substances stored in their granules, including ADP, thromboxane A2 (TXA2), and serotonin. These substances further activate nearby platelets and attract more platelets to the site.

Shape Change: Activated platelets undergo a shape change from smooth discs to spiky, irregular forms, which helps them aggregate more effectively.

Platelet Aggregation:

Formation of the Plug: Activated platelets stick to each other through fibrinogen bridges that bind to platelet surface receptors (e.g., GPIIb/IIIa). This creates a growing cluster of platelets that forms the platelet plug.

Temporary Seal: The platelet plug acts as a temporary seal to minimize blood loss until the more stable fibrin clot can form.

Haemostasis

Haemostasis is the process that stops bleeding and maintains blood in a fluid state within the blood vessels. It involves a series of complex physiological processes that work together to form a clot and prevent blood loss following injury. Haemostasis occurs in three main phases: vascular spasm, platelet plug formation, and coagulation (clotting), followed by clot retraction and fibrinolysis. Each phase involves a distinct set of physiological mechanisms.

1. Vascular Spasm (Vasoconstriction)

Description: When a blood vessel is damaged, the immediate response is vasoconstriction, or narrowing of the blood vessel. This limits blood flow to the area and minimizes blood loss.

Mechanism: The smooth muscle in the blood vessel wall contracts due to local signals, such as:

Neural reflexes triggered by pain receptors.

Endothelin, a potent vasoconstrictor released by endothelial cells.

Serotonin and thromboxane A2 released by activated platelets.

Purpose: This rapid, short-term response reduces blood loss until other haemostatic mechanisms are activated.

2. Platelet Plug Formation (Primary Haemostasis)

Description: Platelets adhere to the site of injury and form a temporary "plug" to block blood loss. This is the first cellular response in haemostasis.

Steps:

Platelet Adhesion:

Von Willebrand factor (vWF), released by damaged endothelial cells, binds to the exposed collagen at the injury site.

Platelets adhere to this complex through their glycoprotein receptors (e.g., GP Ib), anchoring them to the injury.

Platelet Activation:

Once adhered, platelets change shape, releasing granules containing substances like ADP, serotonin, and thromboxane A2. These chemicals amplify the platelet response by recruiting more platelets to the injury.

Platelet Aggregation:

Platelets aggregate, or stick together, through binding of fibrinogen to the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors, forming a platelet plug.

Purpose: The platelet plug provides an initial seal to the injured vessel but is temporary and needs reinforcement from the coagulation cascade.

3. Coagulation (Secondary Haemostasis)

Description: The platelet plug is strengthened by a stable fibrin clot through the activation of the coagulation cascade. This involves a series of clotting factors that lead to the formation of fibrin.

Pathways:

Intrinsic Pathway: Activated by damage inside the vessel, involving clotting factors XII, XI, IX, and VIII.

Extrinsic Pathway: Triggered by external trauma, involving tissue factor (Factor III) and Factor VII.

Common Pathway: Both pathways converge on Factor X, which, together with Factor V, forms the prothrombinase complex. This complex converts prothrombin (Factor II) to thrombin.

Thrombin's Role:

Converts fibrinogen (Factor I) into fibrin, which forms the structural meshwork of the clot.

Activates Factor XIII, which stabilizes the fibrin clot by cross-linking fibrin fibres.

Purpose: To stabilize the platelet plug with a durable fibrin mesh that effectively seals the vessel.

4. Clot Retraction and Wound Healing

Clot Retraction: After the clot forms, platelets contract (using actin and myosin), pulling the edges of the wound together, reducing the size of the clot and injury.

Wound Healing: Platelets release growth factors (e.g., PDGF) that stimulate tissue repair, promoting the healing process.

5. Fibrinolysis (Clot Breakdown)

Description: Once the vessel is repaired, the clot is no longer needed, so it is broken down through fibrinolysis.

Mechanism:

Plasminogen, an inactive protein incorporated into the clot, is converted to plasmin by tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase.

Plasmin breaks down fibrin into fibrin degradation products (FDPs), dissolving the clot.

Purpose: To remove the clot and restore normal blood flow once healing is complete, preventing unnecessary blockage of the vessel.

Regulation of Haemostasis:

Haemostasis is tightly regulated to prevent excessive clotting or bleeding. Key regulators include:

Antithrombin III, which inhibits thrombin and other clotting factors.

Protein C and Protein S, which degrade activated Factors V and VIII.

Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor (TFPI), which inhibits the extrinsic pathway.

Immunology

Different types of immune cells

White Blood Cells (Leukocytes)

A. Granulocytes

Neutrophils:

Function: First responders to bacterial infections; phagocytize and digest pathogens.

Characteristics: Multi-lobed nucleus and granules in the cytoplasm.

Eosinophils:

Function: Combat parasitic infections and play a role in allergic reactions.

Characteristics: Bi-lobed nucleus and large granules that stain with eosin.

Basophils:

Function: Release histamine and heparin during allergic reactions and inflammation.

Characteristics: Bi-lobed nucleus with large granules that stain with basic dyes.

B. Agranulocytes

Lymphocytes:

Function: Key players in adaptive immunity, including recognizing and responding to specific pathogens.

Types:

T Cells: Mature in the thymus and include:

Helper T Cells (CD4+): Assist other immune cells and orchestrate the immune response.

Cytotoxic T Cells (CD8+): Destroy infected or cancerous cells.

Regulatory T Cells: Maintain immune tolerance and prevent autoimmune reactions.

B Cells: Mature in the bone marrow and produce antibodies (immunoglobulins) that neutralize pathogens.

Natural Killer (NK) Cells: Target and kill virus-infected cells and tumour cells without prior sensitization.

Monocytes:

Function: Differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells in tissues; phagocytize pathogens and dead cells, and present antigens to T cells.

Characteristics: Large cells with a kidney-shaped nucleus.

C. Dendritic Cells

Function: Act as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that capture and present antigens to T cells, initiating the adaptive immune response.

Characteristics: Possess long, branch-like projections that enhance their ability to capture antigens.

2. Other Immune Cells

Mast Cells: Located in tissues; release histamine and other mediators during allergic responses and inflammation.

Erythrocytes (Red Blood Cells): While not immune cells, they play a role in transporting oxygen and facilitating immune responses through interactions with immune cells.

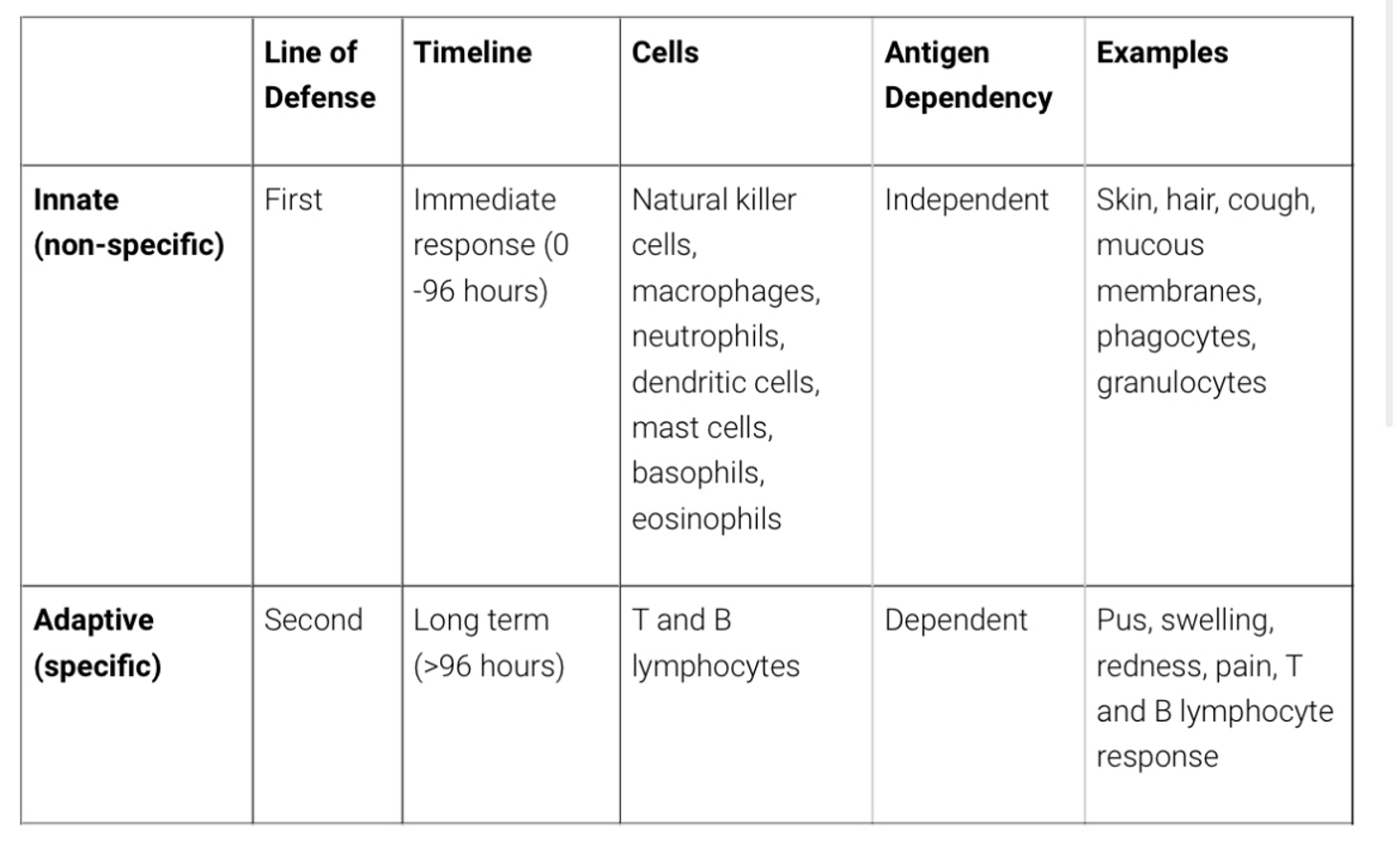

Revisit innate vs acquired immune response

Pathology

Blood cancers

1. Leukaemia

Overview:

Affects the blood and bone marrow, characterized by the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells.

Can be acute (rapid onset) or chronic (slow progression).

Types:

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL): Affects lymphoid cells and progresses quickly. Common in children.

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML): Affects myeloid cells and progresses quickly. More common in adults.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL): Affects lymphoid cells and progresses slowly. Common in older adults.

Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML): Affects myeloid cells and progresses slowly. Associated with a specific genetic abnormality known as the Philadelphia chromosome.

2. Lymphoma

Overview:

Affects the lymphatic system, which is part of the immune system.

Involves abnormal proliferation of lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell.

Types:

Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL): Characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. Often begins in lymph nodes and can spread to other organs.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL): Includes a diverse group of lymphomas that can arise from B cells, T cells, or NK cells. More common than Hodgkin lymphoma.

3. Myeloma (Multiple Myeloma)

Overview:

Affects plasma cells, which are a type of B cell responsible for producing antibodies.

Leads to the accumulation of abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow, disrupting normal blood cell production.

Symptoms:

Bone pain and fractures due to bone damage.

Anaemia, infections, and kidney problems due to the overproduction of abnormal proteins.

Blood diseases

1. Anaemias

Overview:

Characterized by a deficiency in the number or quality of red blood cells or haemoglobin.

Types:

Iron-Deficiency Anaemia: Caused by a lack of iron, leading to insufficient haemoglobin production.

Vitamin Deficiency Anaemias: Due to deficiencies in vitamins B12 or folate.

Haemolytic Anaemia: Caused by the premature destruction of red blood cells.

Aplastic Anaemia: A rare condition where the bone marrow fails to produce enough blood cells.

Sickle Cell Anaemia: A genetic disorder where red blood cells are shaped abnormally, leading to blockages in blood flow.

Thalassemia: A genetic disorder affecting haemoglobin production.

2. White Blood Cell Disorders

Overview:

Affect the body’s ability to fight infections.

Types:

Leukaemia: A group of cancers involving abnormal white blood cell production.

Lymphoma: Cancer of the lymphatic system.

Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Disorders caused by poorly formed or dysfunctional blood cells.

Neutropenia: Low levels of neutrophils, increasing infection risk.

3. Platelet Disorders

Overview:

Affect blood clotting mechanisms.

Types:

Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, leading to increased bleeding risk.

Thrombocythemia: High platelet count, causing clot formation.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): Abnormal clotting and bleeding simultaneously.

Haemophilia: A genetic disorder where blood doesn’t clot normally due to lack of clotting factors (e.g., Haemophilia A and B).

4. Bone Marrow Disorders

Overview:

Affect the production of blood cells.

Types:

Multiple Myeloma: Cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow.

Myeloproliferative Disorders: Overproduction of blood cells (e.g., Polycythaemia vera, Essential thrombocythemia).

Aplastic Anaemia: Failure of the bone marrow to produce sufficient blood cells.

5. Clotting Disorders

Overview:

Affect the blood's ability to clot properly.

Types:

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Formation of clots in deep veins, usually in the legs.

Pulmonary Embolism: Clot travels to the lungs, causing a blockage.

Von Willebrand Disease: A genetic disorder caused by a deficiency of von Willebrand factor, affecting platelet function.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome: An autoimmune disorder causing excessive clotting.

6. Blood Infections

Overview:

Infections that can affect the blood.

Types:

Sepsis: A life-threatening response to infection that can cause systemic inflammation and blood clots.

Bacteraemia: Presence of bacteria in the blood, which can lead to sepsis.

Viremia: Presence of viruses in the blood.

Oral Biology, Disease & Management (OBD&M)

Introduce aspects of Implants

Bone grafts - A bone graft is a surgical procedure where bone material is transplanted to repair or replace bone defects. This can involve using bone from the patient's own body (autograft), from a donor (allograft), or synthetic/biological substitutes.

Types of Bone Grafts:

Autograft: Bone harvested from the patient's own body (e.g., iliac crest).

Allograft: Bone taken from a donor, typically from a bone bank.

Xenograft: Bone derived from an animal source (e.g., bovine).

Synthetic Grafts: Includes materials such as hydroxyapatite or bioactive glass.

Bone graft healing

Inflammation: After implantation, immune cells clear damaged tissue and prepare the area for new growth.

Osteoconduction: The graft acts as a scaffold for new bone growth, allowing cells to migrate and form new bone.

Osteoinduction: Growth factors within the graft stimulate the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into bone-forming osteoblasts.

Osteogenesis: The process where new bone is formed by osteoblasts, particularly when the graft contains live bone cells (in the case of autografts).

Main types of implants/techniques

1.Endosteal Implants

Screw-type: These are the most common type of endosteal implants and are shaped like screws.

Cylinder-type: These implants are smooth and cylindrical.

Blade-type: These implants are flat and have a blade-like shape.

2. Subperiosteal Implants

On the bone: These implants are placed on top of the jawbone but under the gum tissue. They consist of a metal frame that fits onto the jawbone.

3. Zygomatic Implants

Anchored in the cheekbone: These implants are longer and used in cases where there is insufficient bone in the upper jaw. They are anchored in the zygomatic bone (cheekbone).

4. All-on-4 Implants

Full arch prosthesis: This technique involves placing four implants in the jaw to support a full arch of teeth. It is often used for patients who are missing most or all of their teeth.

Pt suitability for implants

Medical history

Systemic Health Conditions

Diabetes: Uncontrolled diabetes can impair healing and increase the risk of infection. Well-managed diabetes may not be a contraindication.

Cardiovascular Diseases: Conditions like hypertension or a history of heart attacks require careful management and consultation with a cardiologist.

Osteoporosis: This condition affects bone density and may complicate implant placement and integration.

Autoimmune Disorders: Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus can affect healing and increase the risk of implant failure.

Cancer: Patients who have undergone radiation therapy in the head and neck region may have compromised bone quality and blood supply.

2. Medications

Bisphosphonates: These drugs, used to treat osteoporosis and other bone diseases, can affect bone healing and increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Anticoagulants: Blood thinners like warfarin or aspirin may increase the risk of bleeding during and after surgery.

Immunosuppressants: Used in organ transplant patients or for autoimmune diseases, these drugs can impair healing and increase infection risk.

3. Lifestyle Factors

Smoking: Significantly increases the risk of implant failure due to impaired blood flow and healing capacity.

Alcohol Consumption: Excessive alcohol use can negatively affect healing and bone metabolism.

Poor Oral Hygiene: Essential for the success of dental implants. Patients must commit to maintaining excellent oral hygiene.

4. Previous Dental and Surgical History

Periodontal Disease: History of gum disease can affect the condition of the jawbone and gums, impacting implant success.

Previous Implant Failures: A history of failed implants may indicate underlying issues that need to be addressed.

Bone Grafting: Previous bone grafting procedures may be necessary if there is insufficient bone to support the implant.

5. Age and Developmental Factors

Age: While there is no upper age limit, younger patients must have completed jaw growth before receiving implants.

Developmental Conditions: Congenital conditions affecting the jaw and teeth may require specialized treatment planning.

6. Allergies and Sensitivities

Metal Allergies: Some patients may have allergies to titanium or other metals used in implants. Alternatives like zirconia implants can be considered.

Implant guidelines

Eligibility criteria for NHS

The likelihood of you receiving NHS-funded dental implants increases when:

You have missing or malformed teeth due to a genetic or inherited condition, such as congenitally missing teeth.

You have lost your teeth due to cancer or other conditions, where your teeth have to be extracted during your course of treatment.

You are experiencing tooth loss and are unsuitable for dentures.

Whether you have lost your teeth due to trauma, or other conditions, guidelines state that all conventional tooth replacement options must be explored first and deemed unsuccessful.

Stages of implant placement

Initial Consultation and Assessment

Medical and Dental History: Review of the patient's medical history, medications, and lifestyle factors.

Clinical Examination: Thorough oral examination to assess the condition of the teeth, gums, and jawbone.

Diagnostic Imaging: X-rays, CT scans, or 3D imaging to evaluate bone quality, bone density, and the exact location for implant placement.

Treatment Planning: Development of a customized treatment plan, including the type and number of implants needed and any additional procedures like bone grafting.

2. Preparatory Procedures (if necessary)

Tooth Extraction: Removal of any damaged or decayed teeth that need to be replaced with implants.

Bone Grafting: If there is insufficient bone to support the implant, bone grafting may be required to augment the jawbone.

Sinus Lift: In the upper jaw, a sinus lift may be necessary if the sinuses are too close to the jawbone.

3. Implant Placement Surgery

Anaesthesia: Local anaesthesia, sedation, or general anaesthesia is administered to ensure comfort during the procedure.

Incision and Drilling: An incision is made in the gum tissue to expose the jawbone. A hole is drilled into the bone to create space for the implant.

Implant Insertion: The dental implant, typically made of titanium or zirconia, is inserted into the drilled hole.

Suturing: The gum tissue is stitched closed over the implant. In some cases, a healing cap is placed on the implant to keep it exposed during the healing process.

4. Osseointegration (Healing Period)

Bone Integration: The implant integrates with the jawbone in a process called osseointegration, which typically takes 3-6 months.

Healing Monitoring: Regular check-ups to monitor the healing process and ensure the implant is properly integrating with the bone.

5. Abutment Placement

Second Surgery: After osseointegration, a minor surgical procedure is performed to expose the implant and attach an abutment (a connector post) to it.

Gum Healing: The gum tissue is allowed to heal around the abutment, which usually takes a few weeks.

6. Prosthetic Attachment

Impression Taking: An impression of the mouth is taken to create a custom crown, bridge, or denture that will be attached to the abutment.

Crown Fabrication: The dental prosthesis is custom-made in a dental lab to match the patient's natural teeth.

Crown Attachment: The final crown, bridge, or denture is attached to the abutment, completing the implant process.

7. Follow-Up and Maintenance

Regular Check-Ups: Scheduled follow-up appointments to ensure the implant is functioning properly and to address any issues.

Oral Hygiene Maintenance: Patient education on maintaining good oral hygiene to ensure the longevity of the implant.

Healing times between stages/appointments

Tooth extraction: 4 to 12 weeks.

Bone grafting: 3 to 6 months.

Implant osseointegration: 3 to 6 months.

Healing after abutment placement: 2 to 3 weeks.

Timings for different implants placement I.e. implant retained denture or implant crown

An Implant-Retained Denture (Overdenture) typically takes 4-9 months - 3-6 months for initial placement and 2-4 weeks healing period for the denture fitting.

A Single Implant with a Crown generally takes 4-12 months - 4-12 week healing period after extraction, 3-6 months after implant placement for osseointegration and 2-3 weeks for gum tissue healing after crown placement.

Multiple Implants with Bridges ranges from 4-12 months with similar stages of healing of single implants.

All-on-4 typically takes 4-6 months - 3-6 months of healing once the implants have fully osseointegrated.

Revisit extractions

Factors that affect healing

Smoking - Smoking reduces blood flow to the gums and bone, impairs the immune response, and interferes with oxygen supply. This can delay wound healing and increase the risk of infection or implant failure.

OH - Poor oral hygiene can lead to bacterial buildup, increasing the risk of post-extraction infections like alveolar osteitis (dry socket) and gum disease, which can impair healing.

Medical history

Pts who have had radiotherapy to head and neck region - Radiotherapy can damage blood vessels and soft tissues in the area, leading to osteoradionecrosis (bone death) and poor healing of the jawbone after an extraction.

Bisphosphonates - These medications, used to treat osteoporosis and certain cancers, can impair bone healing and increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) after extractions or implant placement. Bone turnover and regeneration are reduced.

NOACs & DOACs - These medications thin the blood, increasing the risk of bleeding after extraction. Careful management of anticoagulant therapy is necessary to avoid excessive bleeding.

INR for warfarin pts - For patients on warfarin, it’s important to monitor the International Normalized Ratio (INR), which measures blood clotting time. A high INR indicates a higher risk of post-extraction bleeding complications.

Diabetes - Uncontrolled diabetes impairs the immune system and reduces blood flow, slowing down wound healing and increasing the risk of infection. It can also affect the success of bone integration in dental implants.

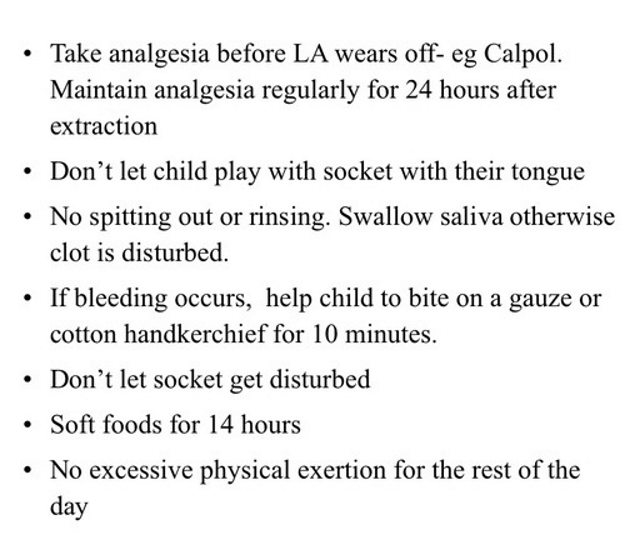

Post-op and pre-op instructions

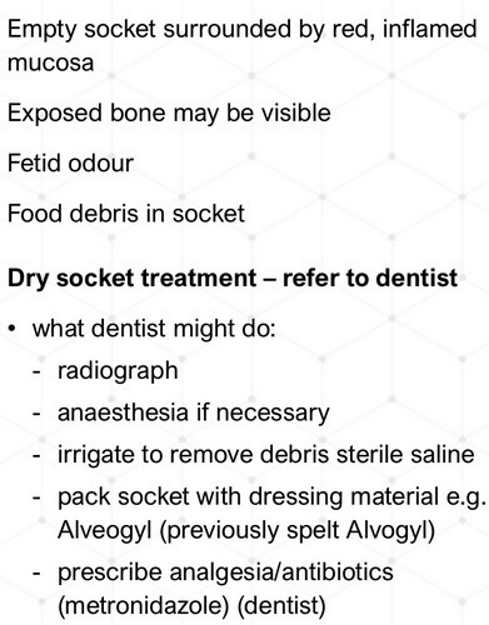

Management of dry socket

Define haematoma - A haematoma is a localized collection of blood outside the blood vessels, usually in liquid form within the tissue. It is typically caused by an injury or trauma that damages the blood vessels, allowing blood to seep out into the surrounding tissues. Haematomas can occur in any part of the body and vary in severity depending on their size, location, and the extent of the bleeding.

Define ecchymosis - refers to a large, flat, and irregularly shaped area of discoloration on the skin caused by bleeding underneath. It is a type of bruise that results from the extravasation (leakage) of blood from broken blood vessels into the surrounding tissues.

What to look for with wound healing

Exudate - Exudate is the fluid that leaks out of blood vessels into nearby tissues and is a natural part of the wound healing process. It helps to keep the wound moist, provides essential nutrients for tissue repair, and assists in the removal of dead tissue and bacteria. The appearance and amount of exudate can vary depending on the stage of wound healing and the presence of any complications.

Clear (Serous) - Normal part of the healing process, especially in the early stages of wound healing. It indicates that the body is protecting and cleaning the wound.

Red (Sanguineous) - Typically seen immediately after injury or surgery. It suggests active bleeding but is usually normal in small amounts.

Pink (Serosanguineous) - Normal during healing. It usually occurs when the wound is starting to heal but still has minor bleeding.

Coloured (Fibrinous) - A sign of infection. Purulent exudate contains white blood cells, dead tissue, and bacteria. This may indicate the presence of bacteria or infection in the wound and should be evaluated by a healthcare provider.

Cloudy (Purulent) - Suggests severe or advanced inflammation. It contains fibrinogen which can form a fibrous clot.

Sutures

Indications for suturing

Wounds with significant tissue separation: This includes lacerations, incisions, and deep cuts.

Preventing infection: Sutures can help close the wound and reduce the risk of pathogens entering.

Promoting proper healing: By bringing the edges of the wound together, sutures help ensure that the wound heals properly.

Minimizing scarring: Properly placed sutures can reduce the formation of excessive scar tissue.

Different suturing materials

Suturing materials can be classified into two main categories:

Absorbable Sutures: These are broken down by the body over time and do not need to be removed. Common types include:

Catgut: Made from animal intestines, though less commonly used now.

Polyglactin (Vicryl): Synthetic and used for many types of soft tissue repairs.

Polyglycolic acid: Another synthetic option that is gradually absorbed by the body.

Non-Absorbable Sutures: These need to be removed after a certain period. Types include:

Silk: A traditional material, but less commonly used due to potential for infection.

Nylon: Strong and used for skin closure.

Polypropylene (Prolene): A strong synthetic material, often used in surgeries requiring long-term support.

Complications of suturing

Inflammation - Can occur due to the body's reaction to the foreign material of the sutures or improper suturing technique. Symptoms include redness, warmth, and swelling at the wound site. Proper placement of sutures, using absorbable materials if appropriate, and maintaining good oral hygiene can help minimize inflammation.

Infection - An infection can develop if bacteria enter the wound. Symptoms include increased pain, redness, swelling, and possibly discharge or fever. Ensure the area is as clean as possible before suturing. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be used in some cases. Patients should follow good oral hygiene practices, including gentle brushing and possibly using an antiseptic mouthwash. Monitoring for signs of infection and prompt treatment with antibiotics if needed are crucial.

Development of scar tissue - All wounds result in some degree of scarring, but improper suturing or excessive tension can lead to hypertrophic scarring or keloids, which are raised and sometimes itchy. Proper suture technique, using appropriate materials, and avoiding unnecessary tension on the sutures can help minimize scarring. For significant scarring, options such as laser therapy or surgical revision may be considered.

Outline/revisit Dentine Hypersensitivity

Types: The place of occurrence of hypersensitivity include: cervical, root, dentine and cemental.

Causes: Arises when tubules found within the dentine become exposed, most commonly caused by gingival recession or enamel wear. This includes dental decay, periodontal disease, trauma or attrition/abrasion.

Signs and Symptoms: Sharp/brief pain of the affected teeth when consuming hot or cold beverages or food, pain when breathing in cold air, pain when consuming sweet or acidic food/drinks. Patients may also experience pain when brushing their teeth or flossing.

Test and Diagnosis: It is diagnosed by taking a thorough medical history and examination of the teeth and gums. Individuals may be asked about dental history, including past diagnosis of gum disease, current oral hygiene habits and medications. During the physical examination, the professional may look for signs of gum recession, tooth decay, tooth erosion and other conditions that may cause hypersensitivity.

Treatment: It depends on the severity of the disease but treatments include:

Desensitising toothpaste to help manage the sensitivity and pain symptoms

Fluoride gel can help improve oral hygiene that may be causing these symptoms

Toothpaste containing calcium sodium phosphosilicate has been shown to relieve dentine hypersensitivity

OHI to improve oral hygiene and reduce the risk of tooth decay and gum disease.

Prognosis: It is often treatable with changes to a person's oral hygiene regimen. Once treatment has taken place, this should be maintained with good oral hygiene and there is no reason why sensitivity should reoccur. With gum recession, this cannot be reversed, but treatment is available to rebuild this or maintain the hypersensitivity in other ways.

Introduce different types of periodontal surgery

Pure muco-gingival

Purpose: This type of surgery focuses on correcting defects in the soft tissue of the gums. It primarily addresses issues related to the attachment of the gingiva to the underlying tissues.

Common Procedures:

Gingival Graft: Involves transplanting tissue from one area of the mouth to another to cover exposed roots or to increase gingival thickness.

Frenectomy: Removal of the frenulum (the fold of tissue connecting the lips or tongue to the gums) if it is causing problems with gum tissue attachment.

Osseous surgery

Purpose: This type of surgery is aimed at correcting defects in the bone supporting the teeth. It is often used to treat periodontitis and improve the bone structure around teeth.

Common Procedures:

Bone Reshaping: Removal of bone to create a smoother surface and improve the contour of the alveolar bone.

Osteoplasty and Osteoectomy: Procedures to contour and reshape the bone to eliminate pockets and promote better adaptation of gum tissue.

Bone Grafting: Replacement of missing bone with graft material to support dental implants or improve bone structure.

Soft tissue plastic surgery

Purpose: Aims to enhance the aesthetic appearance of the gums and improve the functionality of the soft tissues.

Common Procedures:

Gingival Recession Coverage: Techniques like connective tissue grafts to cover exposed root surfaces and reduce sensitivity.

Coronally Advanced Flap: Flap of gum tissue is moved to cover the exposed root.

Free Gingival Graft: Involves taking a graft from the palate and placing it on the recipient site to increase gum tissue volume.

Guided regenerative

Purpose: To regenerate lost periodontal tissues, including bone, cementum, and periodontal ligament, often after the removal of disease or defects.

Common Procedures:

Guided Tissue Regeneration (GTR): Uses barrier membranes to direct the growth of new bone and periodontal tissues. This prevents the rapid growth of epithelial cells into the defect area, allowing more time for bone regeneration.

Bone Grafting: Combined with GTR, bone grafts are used to support new bone formation in the defect areas.

Resective gingival surgery

Purpose: Involves the removal of excess or diseased gum tissue to improve the health and appearance of the gums.

Common Procedures:

Gingivectomy: Removal of inflamed or overgrown gum tissue to reduce pocket depths and improve access for cleaning.

Gingivoplasty: Reshaping the gum tissue to create a more natural contour and address gingival overgrowth.

Public Health (PH)

Implants on NHS

Indications e.g. childhood trauma

In the UK, dental implants are generally considered a private treatment and are rarely available on the NHS. However, in exceptional cases, implants may be provided through the NHS, especially when there is a clinical necessity. When provided on the NHS, they typically fall under Band 3 treatments, which costs around £306.80 in England (2024 pricing). This fee covers all the necessary work, including consultations, surgery, and follow-up care. However, if implants are not available on the NHS, the cost for private treatment can range from £2,000 to £3,000 per implant, depending on various factors such as complexity and location.

Justifications/Indications for Dental Implants on the NHS:

Implants on the NHS are considered when there is a clear medical, functional, or psychological need rather than purely for aesthetic reasons. Common indications include:

1. Trauma

Childhood Trauma: Children who have suffered significant dental trauma resulting in tooth loss (e.g., due to accidents or injuries) may be eligible for implants. Early loss of teeth can affect jaw development and alignment, making implants necessary.

Severe Facial Trauma in Adults: Individuals who experience severe facial or dental trauma leading to the loss of multiple teeth might also qualify for implants on the NHS.

2. Congenital Conditions

Hypodontia: Patients born with congenitally missing teeth (a condition known as hypodontia) may be eligible for implants to restore function and appearance.

Cleft Lip and Palate: Patients with cleft lip or palate may require implants as part of their reconstructive dental treatment.

3. Oral Cancer

Individuals who have lost teeth as a result of oral cancer surgery or cancer treatments may receive implants to help restore function, especially if the cancer has affected their ability to chew or speak.

4. Severe Bone or Dental Disease

Periodontal Disease: In some rare cases, patients with advanced periodontal (gum) disease may qualify for implants if their teeth are no longer salvageable and other options (such as dentures) are unsuitable.

Osteonecrosis or Other Bone Conditions: Patients with certain bone conditions that result in tooth loss may be considered for implants if it improves their quality of life.

5. Other Functional Needs

Difficulty with Dentures: Some patients, particularly those with extreme difficulty wearing traditional dentures due to anatomical or medical reasons (e.g., patients who experience severe gag reflex or have severely resorbed jawbones), may qualify for implants to support more functional prosthetics.

Facial Disfigurement: If tooth loss leads to significant disfigurement and the use of other prosthetics such as bridges or dentures is not possible, dental implants might be provided to improve appearance and quality of life.

Exclusions:

Dental implants are not typically available on the NHS for cosmetic reasons, such as replacing teeth for aesthetic purposes in cases of non-traumatic loss or minor functional deficits. Additionally, patients with smoking habits, uncontrolled diabetes, or severe gum disease that affects the success of implant surgery may be less likely to receive NHS-funded implants.

Data Interpretation (DI)

Epidemiology of dry socket

The global incidence of dry socket is estimated to range from 1% to 5% for routine tooth extractions.

For lower third molar (wisdom tooth) extractions globally, the incidence rises significantly to between 10% and 30%, particularly in cases of difficult or surgical extractions.

Tooth Location: Mandibular (lower jaw) teeth, especially the third molars, have a higher risk of dry socket compared to maxillary (upper jaw) teeth.

Smoking: Smokers are at a significantly higher risk of developing dry socket, with studies suggesting a 2-4 times higher incidence.

Oral Contraceptives: Female patients taking oral contraceptives may be more prone to dry socket due to the effect of oestrogen on blood clotting.

Surgical Complexity: Complex extractions, especially those involving bone removal, are associated with higher rates of dry socket.

In the UK, dry socket occurs approximately 2-5% of all tooth extractions

The incidence in the UK increases to between 10-15%, especially for mandibular third molars.

Age: Dry socket is more common in patients aged 20 to 40 years, particularly in those undergoing wisdom tooth extractions.

See communication and presentation section.

Complex Sentence Structures: The original text contains long, complex sentences that may be difficult for readers to follow. For instance, the first sentence is over 50 words long and includes multiple clauses. Such sentences can overwhelm readers, particularly those who may not be experts in the field.

Alternative Strategy: Break longer sentences into shorter, more digestible parts to improve clarity. Each key point should have its own sentence.

Lack of Clear Flow and Transitions: The text jumps between different concepts, such as comparing one-stage and two-stage procedures, and the description of the blood clot formation, without clear transitions between ideas.

Alternative Strategy: Use clear transition words (e.g., "In contrast," "Furthermore," "Additionally") to guide readers through the flow of information.

Redundant Phrasing: Some ideas are repeated unnecessarily, making the text more difficult to read. For example, the phrase "healing abutment or a provisional prosthesis" is redundant when it can be simplified.

Alternative Strategy: Eliminate redundant phrases or combine them more succinctly.

Jargon Without Explanation: Terms like "first intention healing" and A"peri-implant epithelium" are used without context or explanation. While they may be familiar to experts, these terms can alienate readers unfamiliar with the specific vocabulary.

Alternative Strategy: Define technical terms upon their first use or provide more context to help non-specialists understand.

Inconsistent Time References: The text jumps between describing different stages of healing in terms of days and weeks without a consistent time framework, which could confuse readers.

Alternative Strategy: Present a clear, consistent timeline for healing, referencing specific intervals in either days or weeks throughout.

Imprecise Descriptions: Certain descriptions, such as "the connective tissue aspect of the flap at the abutment-flap interface," are vague and unclear. It's not immediately obvious what is meant by "connective tissue aspect."

Alternative Strategy: Be more precise in describing what is happening to the tissues, using clearer language.

Human Behaviours and Communications (HB&C)

Benefits of telephone review vs. Face to face

Benefits of Telephone Reviews

Convenience:

Patients can receive follow-up care without the need to travel to the clinic, saving time and effort, particularly for those who live far away or have mobility issues.

It also eliminates the need for scheduling around work, school, or family obligations.

Cost-Effectiveness:

No travel costs or time away from work, and it saves clinic resources (chair time, staff, etc.).

Telephone reviews are often quicker, reducing costs for the healthcare provider as well.

Reduced Anxiety:

For some patients, avoiding a dental clinic setting can reduce anxiety, especially if they associate it with discomfort or fear.

Speaking on the phone can be less intimidating, allowing for a more relaxed conversation about post-operative concerns.

Access to Care:

Telephone reviews can help ensure patients who might otherwise skip follow-ups (due to distance, transportation, or health limitations) still receive important aftercare.

It's particularly useful during situations where in-person visits are limited, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic or for immunocompromised individuals.

Monitoring Simple Cases:

For routine, uncomplicated extractions where healing is expected to proceed normally, a telephone review may be sufficient to assess symptoms like pain, swelling, and healing progress.

Patients can report their condition and ask questions, allowing the dentist to provide reassurance or advice without requiring a physical visit.

Efficiency for Healthcare Providers:

Telephone reviews can streamline follow-up care, allowing clinicians to handle more follow-ups in a shorter amount of time, especially for cases that do not require in-person assessments.

Benefits of Face-to-Face Follow-Ups

Direct Clinical Examination:

The dentist can physically examine the extraction site for signs of complications like infection, dry socket, or poor healing, which cannot be done via telephone.

Visual assessment allows for a more thorough evaluation of the patient’s healing progress and any potential issues.

Immediate Treatment:

In the event of complications (e.g., dry socket, infection), face-to-face follow-ups allow the dentist to provide immediate intervention, such as applying a medicated dressing or prescribing antibiotics.

The dentist can also adjust any temporary prosthetics or provide cleaning if needed.

Better Communication:

Face-to-face interaction allows for more nuanced communication. Non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions and body language, can give the dentist more insight into the patient's condition or discomfort level.

Patients may feel more comfortable discussing their concerns in person, and dentists can offer more detailed explanations.

Comprehensive Care:

Dentists can perform a full oral examination, potentially identifying other issues not related to the extraction that might benefit from attention (e.g., decay, gum disease).

Post-extraction care like suture removal or additional cleaning is more efficiently handled in person.

When to Choose Each Approach

Telephone Review: Ideal for straightforward extractions with no complications, where the patient can self-report symptoms like pain, swelling, and healing progress. It works well for patients who are recovering as expected and simply need reassurance or advice.

Face-to-Face Follow-Up: Recommended when complications are suspected, such as prolonged pain, excessive swelling, signs of infection, or dry socket. Also necessary when the dentist needs to perform an in-person procedure like removing sutures or adjusting prosthetics.

Proper post-operative care

A. Immediate Care (First 24-48 Hours)

Bleeding Control:

Bite on Gauze: Patients should bite down gently on a piece of gauze to control bleeding. Keep the gauze in place for 30–60 minutes, changing it as needed.

Avoid Spitting and Rinsing: To allow the blood clot to form properly, patients should avoid spitting, rinsing, or using straws for at least 24 hours.

Pain Management:

Use of Analgesics: Patients should use over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or paracetamol as recommended by their dentist. In more complex cases, prescription pain medication may be necessary.

Ice Pack Application: Apply an ice pack to the face near the surgical site for the first 24 hours to reduce swelling and pain (15 minutes on, 15 minutes off).

Diet:

Soft Food Diet: Encourage patients to consume soft, non-chewy foods for the first few days (e.g., yogurt, soup, mashed potatoes). Hot or spicy foods should be avoided as they can irritate the site.

Avoid Smoking and Alcohol: Both can interfere with healing and increase the risk of dry socket or infection.

Oral Hygiene:

Gentle Cleaning: Patients should maintain oral hygiene by brushing away from the surgical area and avoiding direct contact with the site for the first 24 hours.

Saline Rinse: After 24-48 hours, warm saline rinses (saltwater) can be used gently to keep the area clean.

Individualisation of care

Tailored to Patient Needs:

Medical Conditions: Post-op care may need to be adjusted for patients with diabetes, immunosuppression, or other systemic conditions that can impact healing.

Lifestyle Considerations: Smokers, for example, may be at higher risk of complications such as dry socket or poor healing, so extra precautions should be recommended, such as smoking cessation or nicotine replacement.

Type of Surgery: More complex surgeries, such as bone grafting or multi-stage implants, may require more extensive post-operative care and a longer recovery period.

Communication: It's important to provide clear, personalized instructions based on the patient’s surgical procedure and risk factors. A written set of instructions tailored to the individual should be provided to reinforce verbal advice.

Correct times for suture removal

Standard Timing: Sutures are typically removed between 7 and 14 days after the procedure, depending on the surgery and the patient's healing progress.

Non-Resorbable Sutures: These need to be manually removed by the dentist or surgeon, generally around 7-10 days post-surgery.

Resorbable Sutures: These dissolve on their own, usually within 10-21 days, though timing can vary based on the type of material used.

Factors Influencing Timing:

Type of Surgery: In dental implant procedures or more complex surgeries, the timing for suture removal may extend beyond the usual period.

Healing Progress: If healing is delayed or complications such as infection are present, suture removal may need to be postponed.

Awareness of features of healing

A. Normal Healing Process

First 24-48 Hours: Formation of a blood clot at the surgical site, mild to moderate swelling, and manageable pain.

3-7 Days: The soft tissues begin to repair, and swelling should subside. Pain should significantly reduce, though some tenderness may remain.

2 Weeks: Full epithelialization of soft tissues is usually achieved, and swelling should have completely resolved. The surgical site should appear less inflamed.

Bone Healing (Implant Surgery): In the case of dental implants, the osseointegration process (where the bone fuses with the implant) can take several months (typically 3-6 months).

B. Signs of Healing Problems

Dry Socket: Characterized by severe pain 3-5 days post-extraction, often radiating to the ear, accompanied by an empty socket where the blood clot has dislodged.

Infection: Signs include increased swelling, warmth, redness, pus discharge, persistent pain, and fever. Patients should be advised to seek immediate care if these symptoms occur.

Delayed Healing: If healing appears stalled or the surgical site remains inflamed after 2 weeks, further evaluation is necessary.

Bone Graft/Implant Issues: In the case of implant surgery, mobility of the implant or persistent pain may indicate failure to integrate, necessitating follow-up.

Importance of patient compliance following extractions/surgery

1. Preventing Complications

A. Dry Socket (Alveolar Osteitis)

Cause of Dry Socket: One of the most common complications after tooth extraction is dry socket, where the blood clot protecting the extraction site is dislodged or dissolves prematurely. This can happen if the patient fails to follow instructions to avoid vigorous rinsing, using straws, smoking, or spitting.

Patient Compliance: Proper adherence to instructions helps maintain the blood clot, reducing the risk of dry socket and the severe pain that accompanies it.

B. Infection Control

Increased Risk: Poor post-operative hygiene or failure to take prescribed antibiotics can increase the risk of infection at the surgical site.

Compliance Benefits: Following advice on maintaining oral hygiene (e.g., gentle saline rinses) and taking medications as prescribed helps prevent infections, which can lead to delayed healing, further surgeries, or more severe systemic issues.

2. Optimizing Healing and Recovery

A. Protection of the Surgical Site

Healing Process: Actions such as biting on gauze to stop bleeding, eating soft foods, and avoiding excessive pressure or physical trauma to the area are critical for proper healing. If patients do not follow dietary restrictions or engage in strenuous activities, the surgical site may reopen or be damaged.

Outcome: Compliance ensures optimal healing, reducing pain and speeding up recovery time.

B. Proper Wound Care

Guidance: Patients are instructed to gently clean around the wound and avoid certain activities like smoking or consuming hot foods. Failing to follow these instructions can result in prolonged bleeding, swelling, or even tissue necrosis.

Enhanced Recovery: Proper compliance with wound care prevents unnecessary irritation and promotes faster healing of both soft tissue and bone.

3. Ensuring the Success of Surgical Procedures

A. Dental Implants

Osseointegration Process: For dental implants, the healing process involves osseointegration, where the bone fuses with the implant. This process can be negatively impacted by smoking, poor oral hygiene, or excessive pressure on the implant area.

Patient Compliance: Adherence to post-op care, including avoiding chewing on the implant area and maintaining strict oral hygiene, is essential to avoid implant failure.

B. Bone Grafting and Augmentation

Graft Stability: For patients undergoing bone grafting, stability of the graft site is critical for integration. Poor compliance (e.g., failure to follow dietary restrictions or smoking cessation advice) can lead to graft failure, compromising the success of future treatments such as dental implants.

Improved Outcomes: Following aftercare instructions increases the likelihood of successful bone healing, ensuring future procedures like implants or prosthetics can proceed without issues.

4. Managing Pain and Discomfort

A. Pain Relief

Medications: Pain can be effectively managed with prescribed or over-the-counter analgesics. However, non-compliance (e.g., missing doses or improper medication use) can lead to unnecessary discomfort.

Adherence Benefits: Following pain management protocols ensures that patients remain comfortable during recovery, reducing stress and promoting faster healing.

B. Minimizing Swelling and Bruising

Cold Compresses: Instructions to apply ice packs reduce post-operative swelling and bruising. Ignoring this advice can lead to increased inflammation, pain, and delayed recovery.

Compliance: By following the recommended steps, patients can reduce swelling, improve comfort, and promote faster tissue repair.

5. Long-Term Oral Health and Success

A. Prevention of Future Problems

Hygiene: Patients are often instructed to maintain oral hygiene after surgery to prevent plaque buildup and infection around the extraction site or implant. Failure to comply can lead to long-term oral health issues such as gum disease or tooth decay.

Long-Term Success: Good compliance contributes to the overall health of the mouth, ensuring successful healing and reducing the likelihood of further dental issues.

6. Psychological and Emotional Well-being

A. Reducing Anxiety

Clarity of Instructions: Patients who comply with post-operative instructions often experience less anxiety because they are more likely to recover smoothly without complications.

Peace of Mind: Knowing that they are following proper care guidelines can give patients a sense of control and reduce their concerns about potential problems.

Professionalism and Personal Development and Wellbeing. (P&PDW)

Revisit SoP

Who can place implants?

General Dentists

Basic Implant Procedures: General dentists can place dental implants if they have received adequate post-graduate training in implantology. However, the complexity of the cases they handle may be limited based on their level of experience.

Training Requirements: Dentists need to undergo specific training programs (often including hands-on workshops) in dental implant placement. Courses approved by dental boards or accreditation bodies are usually required.

Specialists

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons: These specialists have extensive training in surgeries involving the jaw and facial structures, including complex dental implant placement.

Periodontists: Specialists in the treatment of gum diseases and the surrounding structures of the teeth. Periodontists often place implants, especially when periodontal health is critical for implant success.

Prosthodontists: Dentists specializing in the restoration and replacement of teeth. While they primarily focus on the design of prosthetics, many prosthodontists are trained in placing implants.

What qualifications are needed to be able to do implants and perio-surgery?

Implants:

General Dentists: Basic training in implant placement may be offered through short courses, but for more advanced procedures, an MSc in Implant Dentistry or equivalent certification is recommended.

Specialists: Oral surgeons, periodontists, and prosthodontists usually undergo additional years of training that include implant procedures during their specialist education programs.

Periodontal Surgery:

Periodontists: Dentists who complete a specialty training program in periodontics are qualified to perform advanced periodontal surgery, including gum grafts, osseous surgery, and guided tissue regeneration.

Training Pathway:

Dental School: Basic surgical skills are taught during dental school.

Specialist Periodontology Training: Additional 3-4 years of full-time specialist training after obtaining a dental degree, often culminating in a Master's degree or specialty certificate.

Certifications: Accredited periodontics programs ensure that specialists are qualified to perform both surgical and non-surgical periodontal treatments.

Who can place sutures?

Dentists:

General Dentists: Any dentist who performs oral surgery or dental extractions is qualified to place sutures as part of their basic dental education.

Specialists: Oral surgeons, periodontists, prosthodontists, and general dentists who perform surgical procedures regularly place sutures in more complex cases, such as implant surgery, bone grafting, or periodontal surgery.

Dental Hygienists and Therapists:

In some jurisdictions, dental hygienists or therapists with additional training may be allowed to place sutures. This is usually regulated by local laws and depends on their expanded scope of practice.

Who can remove sutures?

Dentists:

General Dentists and Specialists: All dentists are qualified to remove sutures as part of routine follow-up care after surgical procedures.

Dental Hygienists and Therapists:

In many places, dental hygienists or dental therapists can also remove sutures under the dentist's direction, particularly in the context of periodontal maintenance or post-surgical care.

Dental Nurses:

In some regions, dental nurses or dental assistants with advanced training are allowed to remove sutures, especially under the supervision of a dentist or specialist. However, this depends on the regulatory framework and country-specific dental practice laws.