Week 9 PSY10007 - Lecture and Module Video - Health, Stress, and Coping

Concise Version

Health Psychology: Definition and Importance

Health psychology is a relatively new field that emerged due to changes in prevalent illnesses.

Mid-century: infectious diseases (tuberculosis, flu) were the main causes of illness and death.

Lifestyle changes, education, and vaccinations helped manage these diseases.

Now: chronic diseases (diabetes, heart disease) are the major health concerns, heavily linked to psychological well-being.

Health psychologists study how people get and maintain health, why people become ill, and how the healthcare system and environment impact health.

Life Expectancy:

Australia: Males - 79 years, Females - 84 years (average).

Indigenous populations have a significantly lower life expectancy.

Health psychologists collaborate with medical professionals (nurses, physicians) and public health officers.

Activities include:

Educating individuals on staying healthy.

Highlighting warning signs of diseases and promoting self-examinations.

Studying the role of stress on physical health and illness.

Supporting people with chronic diseases and their families.

Understanding Stress

Stress: internal processes that occur as we adjust to events or situations.

Stress is a normal part of life and can be motivating.

Excessive stress can negatively impact health.

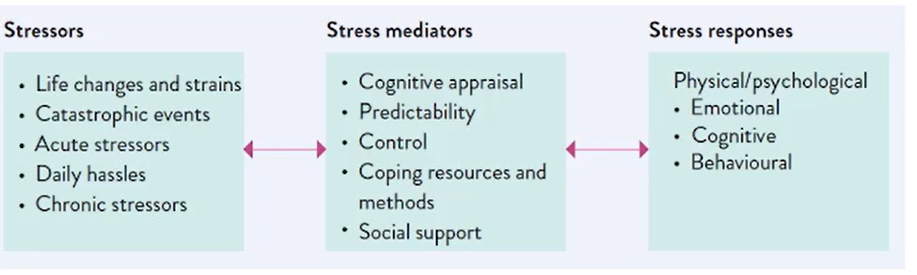

Key constructs involved in stress:

Stressor: The situation or event causing stress.

Stress Mediator: Variables influencing the experience of stress.

Stress Response: The outcome (emotional, behavioral, cognitive, physical).

Example: Going to a new event:

Positive appraisal: optimistic attitude, lower stress response.

Negative appraisal: pessimistic attitude, higher stress response.

Stressors

Stressors don't have to be catastrophic events.

Types of stressors:

Catastrophic events.

Life changes (changing jobs, moving).

Chronic problems (chronic health condition).

Acute problems (fight with a friend).

Daily hassles (traffic).

Accumulated daily hassles can significantly impact health.

Scales to measure stressors:

Social Readjustment Rating Scale: assigns scores to stressors; high scores correlate with higher rates of mental health issues.

Life Experiences Survey: measures life events and cognitive appraisal (optimism vs. pessimism).

Considers other mediators like coping skills and perceived control.

Physical Responses to Stress

Brain perceives danger, releasing chemicals to prepare for fight or flight.

Fight or flight reaction: rapid breathing, increased heartbeat, sweating, shakiness.

Body returns to equilibrium after the danger passes.

Prolonged stress can have long-term physical and psychological consequences.

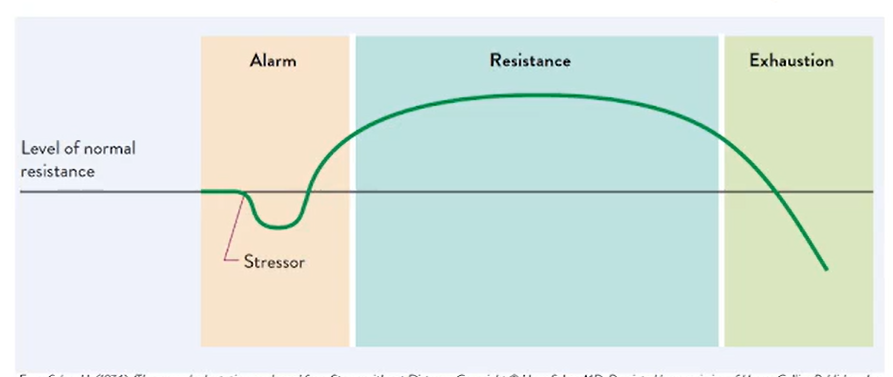

General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) Model: explains what happens when the body doesn't recover quickly from stress.

Alarm Stage: initial response, fight or flight.

Resistance Stage: body appears to cope, but is still working hard.

Exhaustion Stage: burnout, physiological health issues, weakened immune system.

Criticism of GAS: Model doesn't consider appraisal of the situation.

Emotional Responses to Stress

Emotional responses: anger, sadness, fear.

Emotions should return to equilibrium after the stressor is removed.

Prolonged stress or multiple stressors can prevent emotional recovery, leading to:

Irritability.

Anxiety.

Sadness.

Can lead to psychological disorders: anxiety disorder, PTSD, major depressive disorder.

Cognitive Responses to Stress

Stress can impair cognitive abilities: clear thinking, memory, information processing.

Rumination: dwelling on negative thoughts.

Catastrophizing: thinking about worst-case scenarios.

Over-arousal impacts problem-solving ability and attention.

Reliance on mental sets: considering only options that have worked in the past.

Functional fixedness: using objects only for their intended purpose.

Behavioral Responses to Stress

Physical signs: tiredness, strained facial expressions, shaky voice, tremors, jumpiness.

Potentially dangerous behaviors:

Alcohol abuse.

Overeating.

Poor sleep patterns.

Self-harm.

Suicide attempts.

These behaviors are more likely with long-lasting or multiple stressful events.

Therapy focuses on developing adaptive coping strategies.

Stress Mediators

Influence the stress response to a stressor.

Types of stress mediators:

Perception of the event: viewing as catastrophic vs. a challenge.

Predictability: being able to predict the outcome reduces stress.

Perception of control: feeling in control reduces stress.

Coping: problem-focused vs. emotion-focused.

Social support.

Personality: optimism vs. pessimism.

Gender: women use social support more; men have stronger physiological reactions.

Promoting Healthy Behavior

Targeting behaviors that impact physical and psychological health (smoking, unsafe sex).

Addressing obesity through healthy eating and exercise.

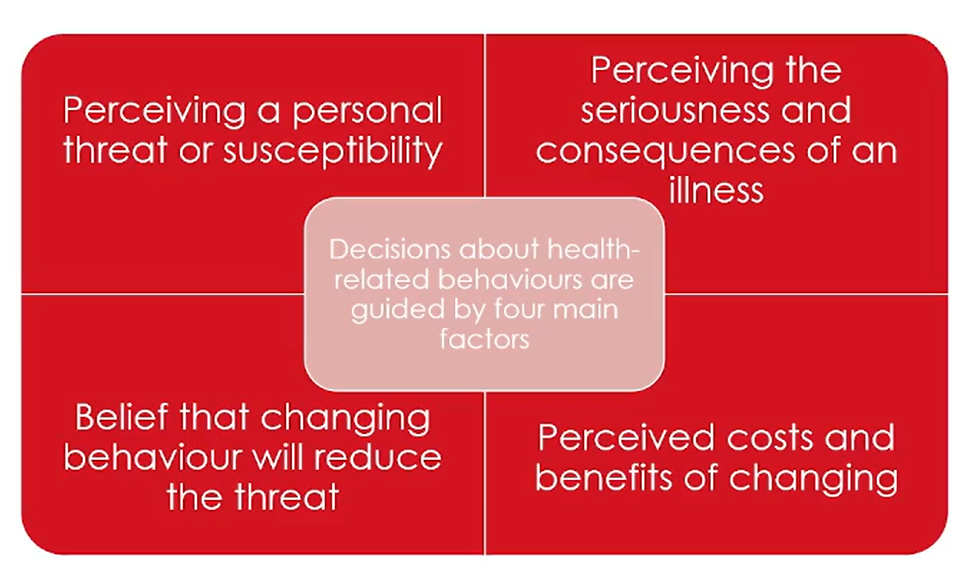

Cognitive Approaches to Health Psychology

Focus on complex thought patterns influencing health-related decisions.

Rosenstock's Health Belief Model: decisions guided by four factors:

Perceived personal threat or susceptibility.

Perceived seriousness and consequences of an illness.

Belief that changing behavior will reduce the threat.

Perceived costs and benefits of changing.

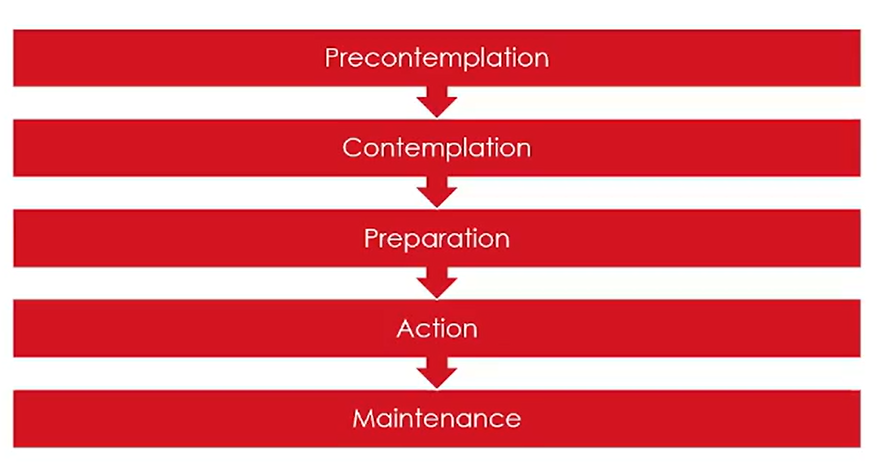

Stages of Readiness Model

Considers readiness to change.

Pre-contemplation: no perceived problem, no intention to change.

Contemplation: aware of the problem, thinking about change.

Preparation: intends to change, making plans.

Action: actively engaging in change.

Maintenance: healthy behavior continues for at least six months.

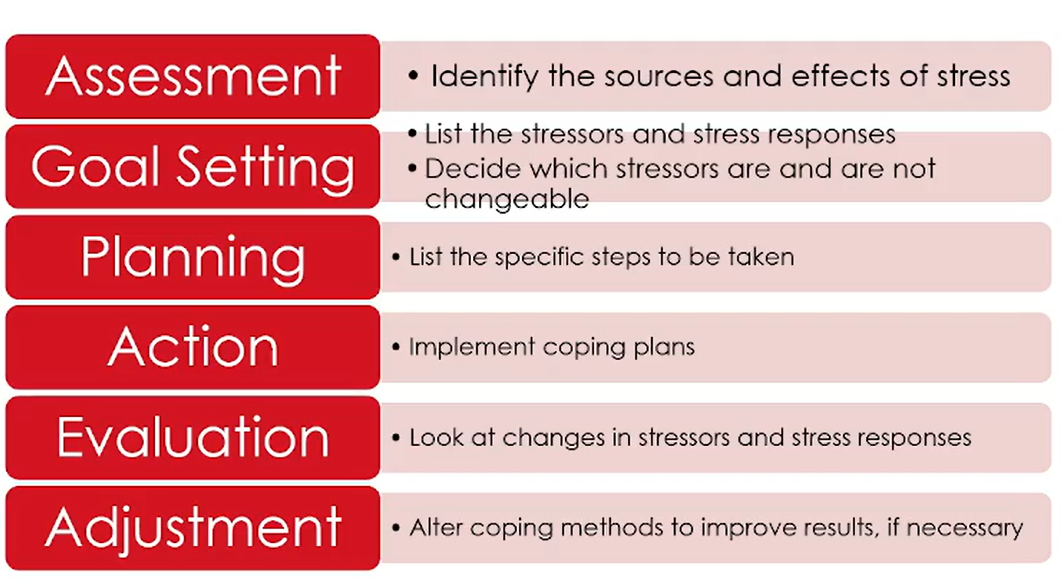

Developing Coping Strategies

Coping strategies mediate the relationship between stressors and stress responses.

Assessment: identify stressors and stress responses.

Goal setting: determine which stressors are changeable.

Planning: list specific steps to introduce coping strategies.

Action: implement the plan.

Evaluation: assess changes in stressors and stress responses.

Adjustments: modify coping strategies as needed.

Cognitive Restructuring

Addresses catastrophic thinking and maladaptive thoughts.

Similar to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Involves changing the way individuals view situations to reduce cognitive stress responses.

Emotional Coping Strategies

Finding social support: seeking support, joining communities.

Social support can positively impact the immune system.

Behavioral Coping Strategies

Changing behaviors to reduce the impact of stressors.

Example: time management to improve morning routine.

Behavioral changes can impact cognitive appraisal of situations.

Physical Coping Strategies

Can be adaptive or maladaptive.

Maladaptive: using drugs and alcohol.

Adaptive: meditation, yoga, exercise, healthy eating, taking breaks, relaxation.

Brain Changes due to Stress

HPA Axis and Cortisol:

Begins with the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis (HPA axis).

Cortisol is released impacting memory.

Amygdala Changes:

The amygdala experiences increased activity.

Hippocampus Deterioration:

Deterioration of electric signals in the hippocampus.

Hippocampus and Stress Control:

Weakening control of stress and memories.

Brain shrinkage:

The brain actually shrinks in size due to loss of synaptic connections.

DNA level and Stress

Epigenetic changes affect receptor development and how genes are expressed.

Reversing Stress Effects

Exercise:

Lowers stress.

Increases hippocampus size.

Improves memory.

Meditation:Improves memory.

Detailed Version

Health Psychology: Definition and Importance

Health psychology is a relatively new and evolving field that emerged in response to significant changes in the patterns of prevalent illnesses and overall healthcare needs. It represents a multidisciplinary approach to health and wellness.

Mid-century (20th Century): The primary causes of illness and death were largely attributed to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, influenza, and pneumonia. These conditions often had acute onsets and were effectively managed through public health interventions and medical advancements.

Due to lifestyle changes, widespread education, and the introduction of effective vaccinations, infectious diseases became less of a threat. These advancements dramatically reduced mortality rates associated with these illnesses.

Present Day: Chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, cancer) have become the major health concerns in developed nations. These conditions are often linked to lifestyle factors and psychological well-being, necessitating a more holistic approach to healthcare.

Health psychologists investigate the psychological, behavioral, and cultural factors that contribute to both physical health and illness. Their studies encompass how individuals maintain health, why they become ill, and the impact of the healthcare system and broader environment on overall health.

Life Expectancy:

Australia: Males typically live around 79 years, while females average 84 years. These figures reflect advanced healthcare and living standards.

Indigenous populations experience a significantly lower life expectancy due to factors such as socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, and cultural determinants of health.

Health psychologists work in collaboration with a wide range of medical professionals, including nurses, physicians, and public health officers, to deliver comprehensive care.

Their activities include:

Educating individuals on strategies for staying healthy, such as adopting healthy diets, engaging in regular exercise, and managing stress effectively.

Highlighting the warning signs and symptoms of diseases and promoting self-examinations (e.g., breast and testicular self-exams) to facilitate early detection.

Studying the role of stress on physical health and illness, exploring how chronic stress can lead to conditions such as cardiovascular disease and immune system dysfunction.

Providing support to individuals with chronic diseases and their families, helping them manage the psychological and emotional challenges associated with long-term illness.

Understanding Stress

Stress: A complex set of internal, psychological, and physiological processes that occur as we adjust to events or situations that disrupt, or threaten to disrupt, our equilibrium.

Stress is a normal and adaptive part of life. It can serve as a motivating factor, prompting individuals to take action and improve their circumstances.

However, excessive or prolonged stress can have detrimental effects on physical and mental health, leading to various health problems.

Key constructs involved in stress:

Stressor: Any event, situation, or demand that causes stress. Stressors can range from minor daily hassles to major life events.

Stress Mediator: Variables that influence the experience of stress, such as coping mechanisms, social support, and individual perceptions of control.

Stress Response: The multifaceted outcome of stress, encompassing emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physical reactions.

Example: Consider the stress associated with attending a new social event:

Positive appraisal: If an individual approaches the event with an optimistic attitude and views it as an opportunity for social interaction, they are likely to experience a lower stress response.

Negative appraisal: Conversely, if an individual approaches the event with a pessimistic attitude and anticipates negative social interactions, they are likely to experience a higher stress response.

Stressors

Stressors are not limited to catastrophic events; they encompass a wide range of experiences and situations that can provoke stress responses.

Types of stressors:

Catastrophic events: These are sudden, unexpected, and overwhelming events such as natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or serious accidents.

Life changes: Major life transitions (e.g., changing jobs, moving to a new city, getting married or divorced) can be significant sources of stress.

Chronic problems: Persistent and ongoing issues (e.g., chronic health condition, financial difficulties, strained relationships) can create long-term stress.

Acute problems: Short-term, but significant challenges (e.g., a fight with a friend, a deadline at work) can trigger acute stress responses.

Daily hassles: Minor irritations and frustrations encountered in daily life (e.g., traffic jams, computer glitches, long lines at the grocery store) can accumulate and contribute to overall stress levels.

Accumulated daily hassles can have a surprisingly significant impact on health. The constant, low-level stress they induce can wear down the body's defenses and increase vulnerability to illness.

Scales to measure stressors:

Social Readjustment Rating Scale: This scale assigns numerical scores to various life stressors. Higher scores are correlated with an increased risk of mental health issues and physical illness.

Life Experiences Survey: This tool measures both life events and cognitive appraisal, assessing the extent to which individuals perceive events as either optimistic or pessimistic. It considers the individual's subjective experience of stress.

Considers other mediators like coping skills and perceived control: In addition to measuring stressors, these scales often take into account mediators such as coping skills and an individual's perceived sense of control, which can significantly influence the stress response.

Physical Responses to Stress

When the brain perceives danger or threat, it initiates a cascade of physiological changes designed to prepare the body for fight or flight.

Fight or flight reaction: This acute stress response involves rapid breathing, increased heartbeat, sweating, and shakiness as the body prepares to confront or flee from the perceived threat.

The body returns to a state of equilibrium (homeostasis) after the danger passes, and physiological arousal subsides.

Prolonged stress can have long-term physical and psychological consequences. Chronic activation of the stress response can lead to conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, anxiety disorders, and depression.

General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) Model: This model, proposed by Hans Selye, explains the body's response to chronic stress when it doesn't recover quickly from the initial stressor.

Alarm Stage: The initial response to stress, characterized by activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the release of stress hormones like adrenaline. This is the fight or flight response.

Resistance Stage: If the stressor persists, the body enters the resistance stage, during which it appears to cope with the stress. However, the body is still working hard to maintain equilibrium, and resources are being depleted.

Exhaustion Stage: Prolonged stress can eventually lead to the exhaustion stage, characterized by burnout, physiological health issues, and a weakened immune system. This stage can increase vulnerability to illness.

Criticism of GAS: The model has been criticized for not adequately considering the individual's appraisal of the situation. The subjective interpretation of a stressor can significantly influence the stress response.

Emotional Responses to Stress

Common emotional responses to stress include anger, sadness, and fear. These emotions serve as signals that something is amiss and prompt us to take action.

Emotions should ideally return to a baseline state of equilibrium once the stressor is removed or resolved. This emotional recovery is essential for maintaining mental well-being.

Prolonged stress or the accumulation of multiple stressors can prevent emotional recovery, leading to enduring negative emotional states such as:

Irritability: Increased sensitivity to minor annoyances and a tendency to react with frustration or anger.

Anxiety: Excessive worry, apprehension, and nervousness, often accompanied by physical symptoms like restlessness and muscle tension.

Sadness: Feelings of unhappiness, dejection, and hopelessness, which can persist even in the absence of a clear trigger.

Chronic emotional dysregulation can lead to the development of psychological disorders, including anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depressive disorder.

Cognitive Responses to Stress

Stress can significantly impair various cognitive abilities, affecting clear thinking, memory, and efficient information processing.

Rumination: This involves dwelling excessively on negative thoughts, replaying past events, and focusing on what went wrong, which can exacerbate stress and anxiety.

Catastrophizing: This cognitive distortion involves thinking about worst-case scenarios and exaggerating the potential negative consequences of events, leading to heightened anxiety and distress.

Over-arousal resulting from stress compromises problem-solving ability and impairs attention, making it difficult to concentrate and make sound decisions.

Reliance on mental sets: Stress can lead individuals to consider only options that have worked in the past, even if they are not appropriate for the current situation, limiting creativity and flexibility.

Functional fixedness: This cognitive bias involves using objects only for their intended purpose, hindering innovative problem-solving by preventing individuals from seeing alternative uses for items.

Behavioral Responses to Stress

Behavioral responses to stress can manifest in various physical signs, including tiredness, strained facial expressions, a shaky voice, tremors, and jumpiness.

Potentially dangerous behaviors that may arise as coping mechanisms during periods of stress include:

Alcohol abuse: Turning to alcohol as a way to numb emotions or escape from stress, which can lead to addiction and related health problems.

Overeating: Consuming excessive amounts of food, often high in sugar and fat, as a means of emotional comfort, leading to weight gain and related health issues.

Poor sleep patterns: Experiencing difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting restful sleep, which can exacerbate stress and impair cognitive function.

Self-harm: Engaging in behaviors such as cutting or burning oneself as a way to cope with intense emotional pain or distress.

Suicide attempts: In severe cases of stress and emotional distress, individuals may attempt to end their lives.

These behaviors are more likely to occur in response to long-lasting or multiple stressful events that overwhelm an individual's coping resources.

Psychotherapy often focuses on developing adaptive coping strategies to help individuals manage stress in healthy ways, reducing reliance on maladaptive behaviors.

Stress Mediators

Stress mediators are factors that influence the individual's stress response to a stressor, either amplifying or attenuating the impact of stress.

Types of stress mediators:

Perception of the event: The way an individual perceives a stressor can significantly impact their stress response. Viewing an event as catastrophic versus a challenge can lead to different emotional and behavioral outcomes.

Predictability: Being able to predict the occurrence and nature of a stressor can reduce stress levels. Uncertainty about what to expect can heighten anxiety.

Perception of control: Feeling in control of a situation or having the ability to influence its outcome reduces stress. Lack of control can lead to feelings of helplessness.

Coping: The coping strategies an individual employs to manage stress can either exacerbate or alleviate its impact. Problem-focused coping involves addressing the stressor directly, while emotion-focused coping involves managing the emotional response to stress.

Social support: Having a strong social network and supportive relationships can buffer the effects of stress. Social support provides emotional comfort, practical assistance, and a sense of belonging.

Personality: Personality traits such as optimism versus pessimism can influence stress responses. Optimists tend to cope more effectively with stress than pessimists.

Gender: Research suggests that women tend to use social support more often as a coping mechanism, while men may exhibit stronger physiological reactions to stress.

Promoting Healthy Behavior

Health psychology plays a crucial role in targeting behaviors that have a significant impact on both physical and psychological health, such as smoking, unsafe sex practices, and sedentary lifestyles.

Addressing obesity through promoting healthy eating habits and regular exercise is another important focus of health psychology interventions.

Cognitive Approaches to Health Psychology

Cognitive approaches in health psychology emphasize the role of complex thought patterns and cognitive processes in influencing health-related decisions and behaviors.

Rosenstock's Health Belief Model: This model proposes that health-related decisions are guided by four key factors:

Perceived personal threat or susceptibility: An individual's belief about their risk of developing a particular health problem.

Perceived seriousness and consequences of an illness: An individual's perception of the severity of a health problem and its potential impact on their life.

Belief that changing behavior will reduce the threat: An individual's belief that adopting a healthier behavior will effectively reduce their risk or mitigate the severity of a health problem.

Perceived costs and benefits of changing: An individual's assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of changing their behavior, weighing the perceived costs against the potential benefits.

Stages of Readiness Model

The Stages of Readiness Model, also known as the Transtheoretical Model, considers an individual's readiness to change their behavior, recognizing that change is a process that occurs in stages.

Pre-contemplation: In this stage, an individual is not aware of having a problem and has no intention to change their behavior. They may be in denial or lack information about the risks of their current behavior.

Contemplation: In the contemplation stage, an individual becomes aware of the problem and starts thinking about making a change. However, they are not yet ready to take action and may be weighing the pros and cons of changing.

Preparation: In the preparation stage, an individual intends to change their behavior and is actively making plans to do so. They may be gathering information, seeking support, and setting goals.

Action: During the action stage, an individual is actively engaging in the new, healthier behavior. This stage requires significant effort and commitment.

Maintenance: In the maintenance stage, the healthy behavior has been sustained for at least six months, and the individual is working to prevent relapse. This stage requires ongoing vigilance and support.

Developing Coping Strategies

Coping strategies play a critical role in mediating the relationship between stressors and stress responses, influencing how individuals manage and adapt to stressful situations.

The process of developing effective coping strategies typically involves the following steps:

Assessment: Begin by identifying the specific stressors an individual is facing and their typical stress responses (emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physical).

Goal setting: Determine which stressors are changeable and realistic to target with coping strategies. Focus on addressing stressors that are within the individual's control.

Planning: Develop a detailed plan that outlines specific steps to be taken to introduce and implement coping strategies. Break down the plan into manageable tasks.

Action: Actively implement the coping strategies outlined in the plan. Put the strategies into practice in real-life situations.

Evaluation: Regularly assess the changes in stressors and stress responses. Determine whether the coping strategies are effective in reducing stress and improving well-being.

Adjustments: Modify coping strategies as needed based on the evaluation. Adapt the strategies to fit the individual's unique needs and circumstances.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring is a therapeutic technique used to address catastrophic thinking and maladaptive thoughts that contribute to stress and anxiety.

This approach is similar to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which aims to modify thought patterns and behaviors to improve mental health.

Cognitive restructuring involves changing the way individuals view situations to reduce cognitive stress responses. It helps individuals challenge and replace negative thoughts with more realistic and adaptive ones.

Emotional Coping Strategies

Emotional coping strategies focus on managing and regulating the emotional responses to stress.

Finding social support is a key emotional coping strategy. This involves seeking emotional support from friends, family, or support groups and joining communities where individuals can share their experiences and feelings.

Research has shown that social support can have a positive impact on the immune system, enhancing its ability to fight off illness and disease.

Behavioral Coping Strategies

Behavioral coping strategies involve changing behaviors to reduce the impact of stressors on daily life.

For example, implementing effective time management techniques can improve one's morning routine, reducing stress and increasing productivity.

Behavioral changes can also have a positive impact on cognitive appraisal of situations, leading to a more optimistic and resilient mindset.

Physical Coping Strategies

Physical coping strategies involve using physical activities and practices to manage stress and promote relaxation.

It's important to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive physical coping strategies. Maladaptive strategies, such as using drugs and alcohol, can have detrimental effects on health.

Adaptive physical coping strategies include:

Meditation: Practicing mindfulness and meditation to calm the mind and reduce stress.

Yoga: Engaging in yoga to improve flexibility, reduce muscle tension, and promote relaxation.

Exercise: Regular physical exercise to release endorphins and improve mood.

Healthy eating: Consuming a balanced and nutritious diet to support physical and mental well-being.

Taking breaks: Incorporating regular breaks into the day to rest and recharge.

Relaxation techniques: Practicing relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and visualization.

Brain Changes due to Stress

Prolonged exposure to stress can induce several changes in the brain, affecting its structure and function.

HPA Axis and Cortisol:

The stress response begins with the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

This leads to the release of cortisol, a stress hormone that can impact memory and cognitive function when levels are chronically elevated.

Amygdala Changes:

The amygdala, which is involved in processing emotions like fear and anxiety, experiences increased activity under chronic stress.

Hippocampus Deterioration:

Chronic stress can lead to deterioration of electric signals in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory and learning.

Hippocampus and Stress Control:

Weakening control of stress and memories occurs due to impaired function in the hippocampus, making it harder to regulate stress responses.

Brain shrinkage:

The brain can actually shrink in size due to the loss of synaptic connections as a result of chronic stress, impacting cognitive abilities.

DNA level and Stress

Stress can induce epigenetic changes that affect receptor development and how genes are expressed, influencing an individual's vulnerability to stress-related disorders.

Reversing Stress Effects

The good news is that many of the adverse effects of stress on the brain can be reversed through various interventions.

Exercise:

Regular physical exercise helps lower stress levels.

It also increases the size of the hippocampus, promoting neurogenesis and improving memory.

Meditation:

Meditation

Images