Chapter 30: Fiscal Policy, Deficits, and Debt

Fiscal policy - Deliberate changes in government spending and tax collections designed to achieve full employment, control inflation, and encourage economic growth

Fiscal policy + the AD-AS model

- Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) - A group of three economists appointed by the president to provide expertise and assistance on economic matters

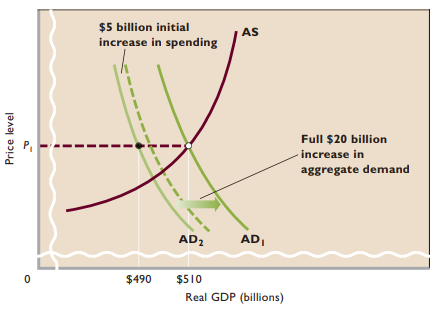

- Expansionary fiscal policy - Used to stimulate the economy during a recession

- (1) increase government spending, (2) reduce taxes, or (3) use some combination of the two

- Budget deficit - Government spending in excess of tax revenues

- Other things equal, a sufficient increase in government spending will shift an economy’s aggregate demand curve to the right

- The government could reduce taxes to shift the aggregate demand curve rightward

- The government may combine spending increases and tax cuts to produce the desired initial increase in spending and the eventual increase in aggregate demand and real GDP

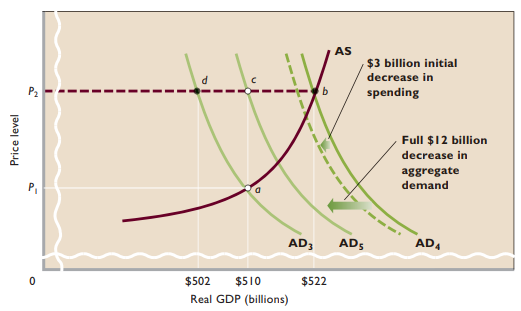

- Contractionary fiscal policy - Used to control demand-pull inflation

- Without a government response, the inflationary GDP gap will cause further inflation

- (1) decrease government spending, (2) raise taxes, or (3) use some combination of those two policies

- Budget surplus - Tax revenues in excess of government spending

- Reduced government spending shifts the aggregate demand curve leftward to control demand-pull inflation

- The government can use tax increases to reduce consumption spending

- The government may choose to combine spending decreases and tax increases in order to reduce aggregate demand and check inflation

Policy options

- Government spending vs. taxes

- No matter the policy, discretionary fiscal policy designed to stabilize the economy can be associated with either an expanding government or a contracting government

Built-in stability

- To some degree, government tax revenues change automatically over the course of the business cycle and in ways that stabilize the economy

- Virtually any tax will yield more tax revenue as GDP rises

- Transfer payments (or “negative taxes”) behave in the opposite way from tax revenues

- Built-in stabilizer - Anything that increases the government’s budget deficit (or reduces its budget surplus) during a recession and increases its budget surplus (or reduces its budget deficit) during an expansion without requiring explicit action by policymakers

- The size of the automatic budget deficits or surpluses—and therefore built-in stability—depends on the responsiveness of tax revenues to changes in GDP

- Progressive tax system - The average tax rate rises with GDP

- Proportional tax system - The average tax rate remains constant as GDP rises

- Regressive tax system - The average tax rate falls as GDP rises

Evaluating fiscal policy

- Must adjust deficits and surpluses to eliminate automatic changes in tax revenues and also compare the sizes of the adjusted budget deficits and surpluses to the level of potential GDP

- Standardized budget - Full employment budget; used to adjust actual Federal budget deficits and surpluses to account for the changes in tax revenues that happen automatically whenever GDP changes

- Cyclical deficit - A by-product of the economy’s slide into recession

Recent US fiscal policy

- Standardized deficits generally smaller than actual deficits

- Actual deficits include cyclical deficits, whereas the standardized deficits do not

Budget deficits + projections

- Subject to large and frequent changes, as government alters its fiscal policy and GDP growth accelerates or slows

Problems, criticisms, and complications

- Problems of timing

- Recognition lag - Time between the beginning of recession or inflation and the certain awareness that it is actually happening

- Administrative lag - Significant lag between the time the need for fiscal action is recognized and the time action is taken

- Operational lag - Lag between the time fiscal action is taken and the time that action affects output, employment, or the price level

- Political considerations

- Incorrectly using fiscal policy for self-gain + political purposes

- Political business cycles - Politicians stimulating the economy before their re-election and then using contractionary fiscal policy to dampen the excessive aggregate demand that they caused with their pre-election stimulus

- Future policy reversals

- Fiscal policy may fail to achieve its intended objectives if households expect future reversals of policy

- State + local fiscal policies usually worsen rather than correct recession + inflation

- Crowding out effect - An expansionary fiscal policy (deficit spending) may increase the interest rate and reduce investment spending, thereby weakening or canceling the stimulus of the expansionary policy

Public debt - Total accumulation of the deficits (minus the surpluses) the Federal government has incurred through time

- US securities - Financial instruments issued by the Federal government to borrow money to finance expenditures that exceed tax revenues

- A wealthy, highly productive nation can incur and carry a large public debt more easily than a poor nation can

- The primary burden of the debt is the annual interest charge accruing on the bonds sold to finance the debt

False concerns of whether or not a large public debt would bankrupt the US

- Bankruptcy - The large U.S. public debt does not threaten to bankrupt the Federal government, leaving it unable to meet its financial obligations

- Refinancing the debt - The government refinances the debt by selling new bonds and using the proceeds to pay holders of the maturing bonds

- Taxation - A tax increase is a government option for gaining sufficient revenue to pay interest and principal on the public debt

- Burdening future generations

Substantive issues relating to the public debt

- Highly uneven income distribution - Because the overall Federal tax system is only slightly progressive, payment of interest on the public debt mildly increases income inequality

- External public debt - In return for the benefits derived from the borrowed funds, the United States transfers goods and services to foreign lenders

- Public investments - Part of the government spending enabled by the public debt is for public investment outlays (for example, highways, mass transit systems, and electric power facilities) and “human capital” (for example, investments in education, job training, and health)