10-11

chp 10 recovery

Recovery

Recovery is an ongoing process of movement toward improvement in health and quality of life. Can have set backs

Recovery is supported by

1. Health: Overcoming or managing one’s disease as well as living in a physically and emotionally healthy way

2. Home: A stable and safe place to live

3. Purpose: Meaningful daily activities, such as a job, school, volunteerism, family caretaking, or creative endeavors, and the independence, income, and resources to participate in society

4. Community: Relationships and social networks that provide support, friendship, love, and hope

for mental illness and SUD → clinical treatment medications, faith-based approaches, peer support, family support, self-care, and other approaches.

six recovery processes:

connectedness, hope, optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment.

Empowerment means that individuals take primary control over decisions about their own care whenever possible.

SAMHSA recovery model

■ Recovery emerges from hope: The belief that recovery is real that people can and do overcome the internal and external challenges, barriers, and obstacles that confront them.

Hope is internalized and can be fostered by peers, families, providers, allies, and others.

Hope is the catalyst of the recovery process.

■ Recovery is person-driven: Self-determination and self-direction

optimize their autonomy and independence by leading, controlling, and exercising choice over the services and supports that assist their recovery and resilience.

In so doing, they are empowered and provided the resources to make informed decisions, initiate recovery, build on their strengths, and gain or regain control over their lives.

■ Recovery occurs via many pathways: Individuals are unique

Recovery pathways are highly personalized.

They may include professional clinical treatment, use of medications, support from families and in schools, faith-based approaches, peer support, and other approaches.

Recovery is nonlinear, characterized by continual growth and improved functioning that may involve setbacks.

setbacks are natural →resilience

Abstinence is the safest approach for those with substance use disorders.

In some cases, recovery pathways can be enabled by creating a supportive environment. This is especially true for children, who may not have the legal or developmental capacity to set their own course.

■ Recovery is holistic: whole life, including mind, body, spirit, and community.

addresses self-care practices, family, housing, employment, education, clinical treatment for mental disorders and substance use disorders, services and supports, primary health care, dental care, complementary and alternative services, faith, spirituality, creativity, social networks, transportation, and community participation.

■ Recovery is supported by peers and allies: Mutual support and mutual aid groups, including the sharing of experiential knowledge and skills, as well as social learning.

Peers provide each other with a vital sense of belonging, supportive relationships, valued roles, and community. + helping others and giving back to the community, individuals also help themselves.

especially in 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

peer support specialists: facilitate peer-operated supports and services may be trained and/or certified in supportive skills; all participants share the experience of lived experience with mental illness and, as such, can provide a unique perspective for support and trust in ongoing relationships.

Professionals provide clinical treatment and other services that support individuals in their chosen recovery paths.

Peer supports for families are very important for children with behavioral health problems and can also play a supportive role for youth in recovery.

■ Recovery is supported through relationship and social networks: the presence and involvement of people who believe in the person’s ability to recover; who offer hope, support, and encouragement; and who also suggest strategies and resources for change.

leave unhealthy roles → new roles (e.g., partner, caregiver, friend, student, employee) = greater sense of belonging, personhood, empowerment, autonomy, social inclusion, and community participation.

■ Recovery is culturally based and influenced: Services should be culturally grounded, attuned, sensitive, congruent, and competent as well as personalized to meet each individual’s unique needs.

SAMHSA (2017) stresses that mental health and substance addiction services must not only respect and actively address the cultural and linguistic needs of diverse populations but should also reduce disparities in access to care.

■ Recovery is supported by addressing trauma: ~ with alcohol and drug use, mental health problems, and related issues.

Services and supports should be trauma-informed to foster safety (physical and emotional) and trust as well as promote choice, empowerment, and collaboration.

■ Recovery involves individual, family, and community strengths and responsibilities: Individuals, families, and communities have strengths and resources that serve as a foundation for recovery.

individuals have a personal responsibility for their own self-care and journeys of recovery + should be supported in speaking for themselves.

social responsibility and should have the ability to join with peers to speak collectively about their strengths, needs, desires, and aspirations.

Families and significant others have responsibilities to support their loved ones.

Communities have responsibilities to provide opportunities and resources to address discrimination and to foster social inclusion and recovery.

■ Recovery is based on respect: Community systems, social acceptance, and appreciation of people’s lived experience with mental illness and substance use problems—including protecting their rights and eliminating discrimination.

There is a need to acknowledge that taking steps toward recovery may require great courage.

Self-acceptance, developing a positive and meaningful sense of identity, and regaining belief in oneself are particularly important.

Patient centered models:

traditional goal for a patient has been described as “Patient will comply with prescribed medication regime.”

patient-centered recovery model stated as, “Patient will discuss preferences, advantages, and disadvantages of psychotropic medication in the management of his or her illness.”

Tidal Model

power of metaphor to engage with the person in distress.

The metaphor of water is used to describe how individuals in distress can become emotionally, physically, and spiritually shipwrecked

person-centered approach → individual’s personal story

10 Tidal Commitments:

1. Value the voice:

“The person’s story represents the beginning and endpoint of the helping encounter, embracing not only an account of the person’s distress, but also the hope for its resolution” (p. 95).

actively listen to the person’s story and to help the person record the story in their own words.

2. Respect the language: “The language of the story—complete with its unusual grammar and personal metaphors—is the ideal medium for illuminating the way to recovery.

Practitioner competencies include helping individuals express in their own language their understanding of personal experiences through use of stories, anecdotes, and metaphors.

3. Develop genuine curiosity: to better understand the storyteller and the story.

Practitioner competencies include showing interest in the person’s story, asking for clarification of certain points, and assisting the person to unfold the story at their own pace.

4. Become the apprentice: Individual are the experts on their life stories, and they must be the leader in deciding what needs to be done.

learning something if open minded + eager to learn like na apprentice

Practitioner competencies include developing a plan of care for the individual, based on expressed needs or wishes, and helping the individual identify specific problems and ways to address them.

5. Use the available toolkit:

what has worked and what might work.

Practitioner competencies include helping individuals identify what efforts may be successful in relation to solving identified problems AND which persons in the individual’s life may be able to provide assistance.

6. Craft the step beyond: “Any ‘first step’ is a crucial step, revealing the power of change and potentially pointing towards the ultimate goal of recovery” (p. 96).

Practitioner competencies include helping individuals determine what kind of change would represent a step toward recovery and what they need to do to take that first step toward that goal.

7. Give the gift of time: Change happens when the individual and practitioner spend quality time in a therapeutic relationship.

Practitioner competencies include acknowledging (and helping the individual understand) the importance of time dedicated to addressing the needs of the individual and the planning and implementing of care.

8. Reveal personal wisdom: People often do not realize their own personal wisdom, strengths, and abilities, so that it might be used to sustain the person throughout the voyage of recovery.

Practitioner competencies include helping individuals to identify personal strengths and weaknesses and to develop self-confidence in their ability to help themselves.

9. Know that change is constant:

Professional competencies include helping individuals develop awareness of the changes that are occurring and how they have influenced these changes.

10. Be transparent: helping the person understand exactly what is being done and why

Professional competencies include ensuring that individuals are aware of the significance of all interventions and that they receive copies of all documents related to the plan of care

Wellness recovery Action Plan

storing information (e.g., a notebook, computer, or tape recorder) + possibly a friend, health-care provider, or other supporter to give assistance and feedback

Steps:

develop wellness toolbox that were used in the past to relieve s/s

daily maintenance list: 3 parts:

description how they feel when experiencing wellness

use tool box as reference, make list of things they have to do each day for maintenance (realistic)

have list of things they have to do

triggers: 2 parts

list events that would cause distress

use tools from wellness to plan what you would do when that happens

early warning signs: 2 parts:

identify subtle signs

anxiety, forgetfulness, lack of motivation, avoiding others or isolating, increased irritability, increase in smoking, using substances, or feeling worthless and inadequate

develop plan to respond to early signs

things are getting worse: 2 parts

list the things that indicate that situation is getting worse (s/s produce great discomfort but can still take action)

irrational responses, h/a, not eating/ sleeping, social isolation, SUB/ smoking, paranoia, hallucinations

plan what to do to combat these s/s with specific instructions

call HCP, get social support, prevent self-harm, do everything on check list, use more tools

crisis planning: for caregivers since pt cannot take take of themselves

get info on what the pt is like when well → identify s/s for crisis

get pt’s supporters contact info

identify pt’s preferences regarding tx, health hx,

find acceptable facilities incase prefered does not work

extensive description of what supporters have to do in case of crisis

make list of indicators that support is no loner required

crisis plan is to be sign with presence of 2 witnesses

psychological recovery model

does not emphasize the absence of symptoms but focuses on individuals’ self-determination in the course of their recovery process.

■ Hope: Finding and maintaining hope that recovery can occur

■ Responsibility: Taking responsibility for one’s life and well-being

■ Self and identity: Renewing the sense of self and building a positive identity

■ Meaning and purpose: Finding purpose and meaning in life

Steps:

moratorium: despair and confusion

hopelessness

feels with no control

don’t knwo who they are as a person → lost sense that they are valuable

mental illness challenges fundamental beliefs → loss of meaning and life

awareness: realizes possibility of recovery exists

dawn of hope that can come from others (close or inspired, or faith/spirituality)

develops awareness that need to take back control of life

realizes they are themselves independent of their own mental illness

personal comprehension of their illness

preparation resolve to beginning of recovery

hope from internal and external sources helps create goals. Identify strengths and weakness, information, seek support system

takes responsibility by learning about illness and taking care of their own ADL

willing to take risks to reestablish themselves → new identity

living according to values gives meaning to their life

rebuilding: necessary steps to work towards goal

hope: increase hope and encourage own pace recovery. inc hope with each success

actively takes control of life and manages s/s

enhances new self seperated from illness

with identity and realistic goals → new meaning

growth

skills nurtured and feels optimism and hope for rewarding future

confidence in managing s/s and resilient to relapses

strong positive sense of self

more profound sense of meaning. educates others about their expiriences

Nursing process and recovery models

assessment

tidal: explores pt story, records, identifies problems, strengths and weaknesses

wrap: develop wellness toolbox, identifies strength and weaknesses, nurse provides assistance + feedback

psychological: pt is hopeless, powerless, seeks to understand illness → nurse offers hope → pt gains awareness

interventions

tidal: analysis tools that worked in the past and that might work in future

makes realistic goals and decide what to do as 1st step

give positive feedback for changes made and encourages max independence but offers assistance if needed

wrap: daily maintenance list, triggers, plan for early, worsening, and crisis s/s

psych: identifies strengths/ weaknesses, starts recovery and learns how to manage s/s, set goals, and encourage meaning of life

outcome

tidal: pt knows change is ongoing, feels empowered to manage own self,

wrap: pt develops self-managing skills + hope for brighter future

psych: pt develops self identity separated from illness, maintains commitment to recovery despite setbacks, has sense of hope

basically:

tidal is about pt’s story and empowering to manage self despite constant changes (person-centered)

WRAP is like planning crisis prevention with wellness tools

psychological is when pt is in crisis and nurse gives and helps the patient develop hope, self-respect, identity, and meaning of life

chp 11 suicide prevention

Suicide is not a diagnosis or a disorder; it is a behavior. Specifically, it is the act of taking one’s own life

population of higher risk:

native americans

LGBTQ

veterans

people in justice or child welfare

complex interaction of mental illness, SUD, painful liss, exposure to violence, social isolation

myths vs facts:

suicide happens w/o warning vs suicidal give definite clues about intentions (may be ignored by others)

cannot stop suicidal people vs ambivalent with feelins of dying and living

once suicidal, always suicidal vs. may fluctuate (if provided resources may stop, but more attempts = more likely)

improve after depression means no more suicide vs suicide occurs there due to more energy

it is inherited vs no it is not. mental illnesses are and if it has been witnessed by a close member = may inc risk

all suicidal people of mentally ill vs wrong

suicidal attempts are manipulative/ attention seeking vs this should be approached with act in mind. can be a cry for help

overdose of drugs is higher suicide vs gunshot

it is impulsive vs not it is not, it is often planned, imagined, and contemplated

young children (5-12) are not suicidal vs can be

risk:

divorced men, or widowed

more women attempt but men often succeed

women overdose, men use arms

women are more likely to seek help

age: rates increase with men

2nd lead cause for adolescent

starting to notice in younger children

religion: more protective of acts and not ideation

financial strain and unemployment

mental illness, (traumatic brain injury, sleep disorders, and HIV/AIDS)

LGBTQ

bullying

American Indian and non-Hispanic whites

occupation:

health care, dentists,

law enforcers, lawyers

artists

insurance agents

theories

psychological

anger turned inward: self hatred

hopelessness

hx of aggression and violence more in suicide attempts not ideation

shame and humiliation

sociological

Durkheim: the more individuals felt out of society = more suicide

egoistic: feels separated from mainstream society

altruistic: excessively integrated. For the good of the society

anomic: due to changes in individual’s life

Interpersonal: Durkheim + from suicide ideation → attempts is a process

low connects + feeling like a burden inc ideation → expose them selves to repeated pain or violence = makes them less fearful from attempts

3-step theory: impulsivity inc when made previous attempts

pain + hopelessness = inc ideation

connected prevents suicide ideation to become attempts, but if exceed connectiveness = inc action

attempt with strong ideation is made if one has the capacity to do so

biological

genetics: varieties of gene for tryptophan hydroxylase (~ enzyme for synthesis of 5-TH; so if low= low 5-TH = anxiety+ depression)

variation of prefrontal cortex

neurochemical: weak predictors but inc risk if altered levels of 5-TH, GABA, dopamin, CRH

strong: cytokines, low level of fish oils

nursing process

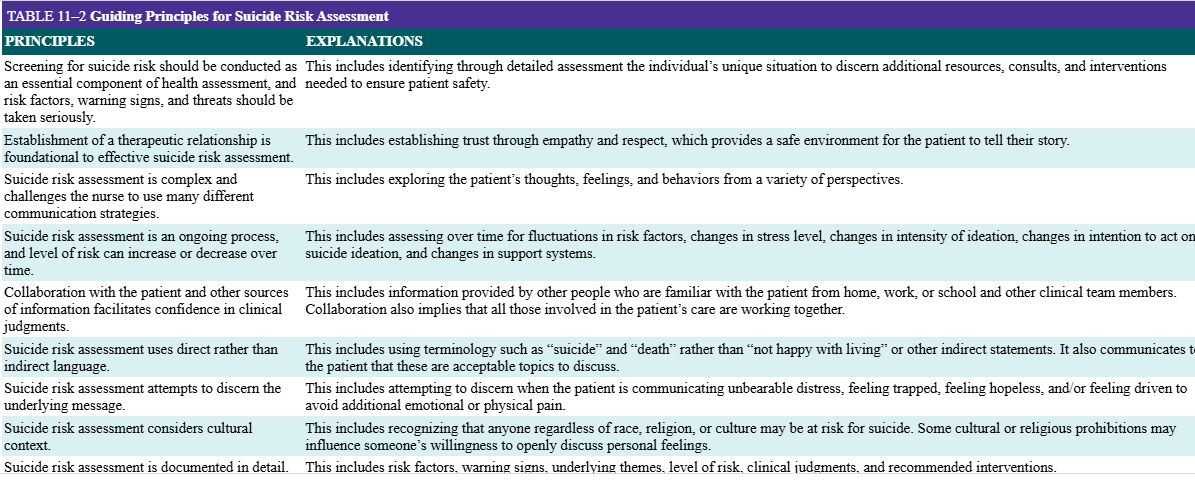

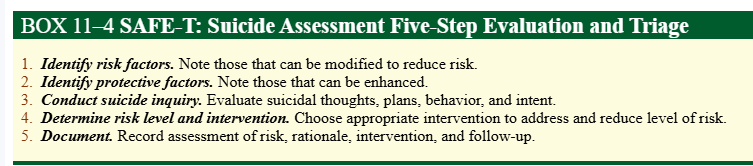

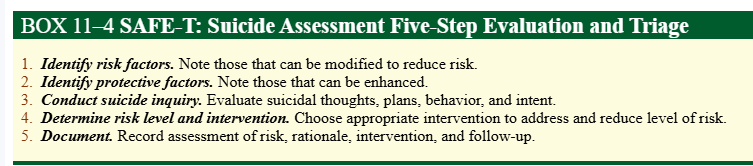

assessment: ideas (thoughts), plans (intentions), and attempts (behavior)

suicidal self-injury vs nonsuicidal self-injury (method to release emotions but to also communicate severity of distress

Protective factors vs suicide:

Resilient temperament

Social competency

Skills in problem-solving, coping, and conflict resolution

Perception of social support from adults and peers

Positive expectations, optimism for the future; identification of future goals

Connectedness to family, school, community

Presence and involvement of caring adults (for adolescents)

Integration in social networks

Cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and encourage preservation of life

Access to quality social services and clinical health care for mental, physical, and substance use disorders

Support through ongoing medical and mental health-care relationships

Restricted access to highly lethal means of suicide

Major depression and bipolar are more likely. SUD, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, substance use disorders, anorexia nervosa, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and borderline and antisocial personality disorders. Chronic and terminal physical illnesses

behavioral clues: giving away prized possessions, getting finacial affairs in order, writing suicide notes, sudden shift of mood

verbal clues: direct / indirect

suicide-specific rumination: Asking how frequently the patient is thinking about suicide ideas, intentions, and plans helps to discern this level of risk

lethality

interpersonal support system

medical. psych, family hx

coping strategies

analysis of suicidal crisis:

■ The precipitating stressor: Life stresses accompanied by an increase in emotional disturbance include the loss of a loved person either by death or by divorce, problems in major relationships, changes in roles, or serious physical illness.

■ Relevant history: Has the individual experienced multiple failures or rejections that might increase their vulnerability for a dysfunctional response to the current situation?

■ Life-stage issues: The ability to tolerate losses and disappointments is often compromised if the individual is also struggling with the developmental tasks associated with different life stages (e.g., adolescence, midlife, old age).

Presenting s/s: IS PATH WARM

Ideation: Has suicide ideas that are current and active, especially with an identified plan

Substance abuse: Has current and/or excessive use of alcohol or other mood-altering drugs

———

Purposelessness: Expresses thoughts that there is no reason to continue living

Anger: Expresses uncontrolled anger or feelings of rage

Trapped: Expresses the belief that there is no way out of the current situation

Hopelessness: Expresses lack of hope and perceives little chance of positive change

———

Withdrawal: Expresses desire to withdraw from others or has begun withdrawing

Anxiety: Expresses anxiety, agitation, and/or changes in sleep patterns

Recklessness: Engages in reckless or risky activities with little thought of consequences

Mood: Expresses dramatic mood shifts

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

directly stating about their suicidal intent (stated intent) but also the amount of thinking, planning, and behaviors associated with suicide ideation (reflected intent) and the suicide intent that is withheld from the nurse (withheld intent).

CASE: Chronological Assessment of Suicide events

Normalizing communicates that the patient is not the only one who experiences suicidal ideation.

Example: “Sometimes when people are in a lot of emotional pain, they have thoughts of killing themselves. Have you had any thoughts like that?”

■ Asking about behavioral events rather than the patient’s opinions may elicit more concrete information. (more objective)

Example: “What did you do when you had those thoughts?” “How many pills did you take?” “What happened next?”

■ Gentle assumptions encourage further discussion by assuming there is more to tell.

Example: “What other times have you attempted suicide?”

■ Denial of the specific is helpful when a patient generally denies suicidal ideation. This strategy encourages more in-depth thought and response by asking questions that might trigger memories of specific events.

Example: After the patient denies suicidal ideation in response to a general question, the nurse asks more specifically, “Have you ever had thoughts of overdosing?” “Have you ever had thoughts about shooting yourself?”

■ Chronologically exploring the presenting suicide event, recent suicide events, past suicide events, and finally the immediate suicide events can broaden the nurse’s understanding of the patient’s immediate suicidal intent in the context of their behavior over time.

Example: Ask the patient about the event that precipitated this episode of care: “Tell me about the event that led you to be hospitalized,” and then ask about any other recent events: “When was the last time you attempted suicide prior to this event? Tell me more about that event” (as well as their history of suicidal behavioral over time). Finally, explore immediately current ideation and intent: “Tell me about your level of risk right now. Current ideas? Intensity? Intentions?”

nursing dx

■ Risk for suicide related to feelings of hopelessness and desperation

■ Hopelessness related to absence of support systems and perception of worthlessness

■ Ineffective coping related to extreme stress, crisis, feeling trapped, poorly developed coping skills

interventions for outpatient setting

■ The person should have immediate access to support systems since after hospital discharge is a high-risk period→ stay with family or hospitalization

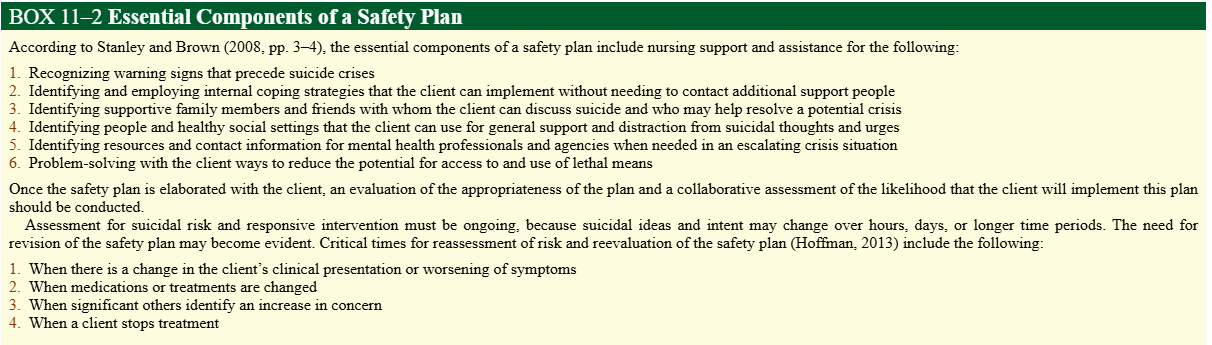

■ A detailed safety plan. This intervention explores with clients what they will do to stay safe if there is a repeat or increase in suicidal thoughts or urges.

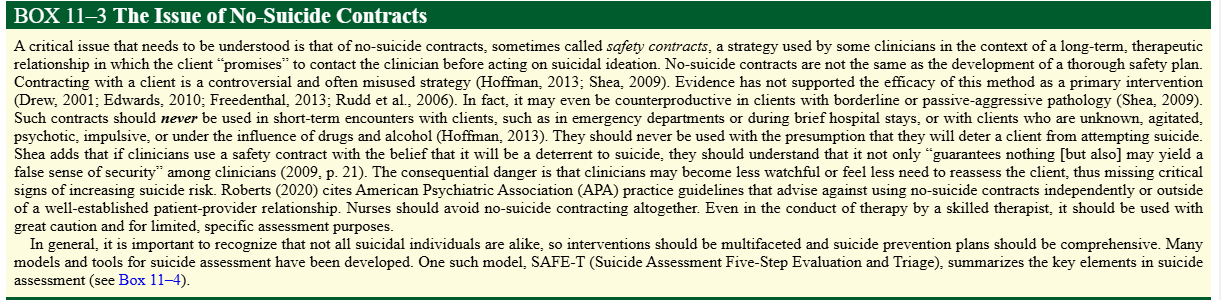

■ A safety plan is NOT no-suicide contract.

■ Enlist the help of family to ensure that the home environment is safe from dangerous items + give emergency contact

■ Appointments may need to be scheduled daily or every other day at first until the immediate suicidal crisis has subsided.

■ Establish rapport and promote a trusting relationship. It is important for the suicide counselor to become a key person in the client’s support system at this time. Accept the client’s feelings in a nonjudgmental manner.

■ Discuss the current crisis situation in the client’s life. Use the problem-solving approach. Offer alternatives to suicide while at the same time empathizing with the client’s pain that led to viewing suicide as an option (Jobes, 2012). An example of this kind of communication might be:

“I understand how this emotional pain you’ve been experiencing led you to consider suicide, but I’d like to explore with you some alternative ways to decrease your pain and to identify some reasons for continuing to live.”

■ Help the client identify areas that are within their control and those that are not. Discuss feelings associated with these control issues. It is important for the client to feel some control over their life situation in order to perceive a measure of self-worth.

■ Initially a prescription is written for a small number of pills to minimize the risk of intentional overdose (potentially fatal consequences are a particular concern with tricyclic antidepressant overdose).

■ Psychological interventions that have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing suicidal behavior include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), cognitive behavior therapy, and CAMS

interventions for friends and family

■ Take any hint of suicide seriously.

■ Do not keep secrets. If a suicidal person says, “Promise you won’t tell anyone,” do not make that promise. Suicidal individuals are ambivalent about dying, and suicidal behavior is a cry for help. It is that ambivalence that leads the person to confide to you the suicidal thoughts. Get help for the person and for you. The national hotline 1-800-SUICIDE is available 24 hours a day.

■ Be a good listener. Let them know you are there for them and are willing to help them seek professional help.

■ Many people find it awkward to put into words how another person’s life is important for their own well-being, but it is important to stress that the person’s life is important to you and to others. Emphasize in specific terms the ways in which the person’s suicide would be devastating to you and to others.

■ Express concern for individuals who express thoughts about suicide. veiled comments or comments that sound as if they are joking, or people may be withdrawn and reluctant to discuss what they are thinking → acknowledge the pain and feelings of hopelessness, and encourage individuals to talk to someone else if they do not feel comfortable talking with you.

■ Familiarize yourself with suicide intervention resources, such as mental health centers and suicide hotlines.

■ Ensure that access to firearms or other means of self-harm is restricted.

■ Communicate caring and commitment to provide support. Fleener (n.d.) offers the following suggestions for interacting with people who are suicidal:

■ Acknowledge and accept their feelings and be an active listener.

■ Try to give them hope and remind them that what they are feeling is temporary.

■ Stay with them. Do not leave them alone. Go to where they are, if necessary.

■ Show love and encouragement. Hold them, hug them, touch them. Allow them to cry and express anger.

■ Help the person seek professional help.

■ Remove any items from the home with which the person may harm themselves.

■ If there are children present, try to remove them from the home. Perhaps friends or relatives can assist by taking the children to their home. This type of situation can be extremely traumatic for children.

■ DO NOT judge suicidal people, show anger toward them, provoke guilt in them, discount their feelings, or tell them to “snap out of it.” This is a very real and serious situation to suicidal individuals. They are in real pain. They feel the situation is hopeless and that there is no other way to resolve it aside from taking their own life.

Intervention With Families and Friends of Suicide Victims

Macnab (1993) identified the following symptoms that may be evident in family and friends after the suicide of a loved one:

■ A sense of guilt and responsibility

■ Anger, resentment, and rage that can never find its “object”

■ A heightened sense of emotionality, helplessness, failure, and despair

■ A recurring self-searching: “If only I had done something,” “If only I had not done something,” “If only …”

■ A sense of confusion and search for an explanation: “Why did this happen?” “What does it mean?” “What could have stopped it?” “What will people think?”

■ A sense of inner injury; family feels wounded; does not know how they will ever get over it and get on with life

■ A severe strain placed on relationships; a sense of impatience, irritability, and anger possible between family members

■ A heightened feeling of vulnerability to illness and disease possible with this added burden of emotional stress

■ Encourage the survivors to talk to each other about the suicide and respond to each other’s viewpoints and reconstructing of events. Share memories.

■ Be aware of any blaming or scapegoating of specific family members. Discuss how each person fits into the family situation, both before and after the suicide.

■ Listen to feelings of guilt and self-persecution. Gently move the individuals toward the reality of the situation.

■ Encourage the family members to discuss individual relationships with the lost loved one. Focus on both positive and negative aspects of the relationships. Gradually, point out the irrationality of any idealized concepts of the deceased person. The family must be able to recognize both positive and negative aspects about the person before grief work can be resolved. No two people grieve in the same way. It may appear that some family members are “getting over” their grief faster than others. All family members must be educated that if this occurs, it is not because those family members “care less”—it is just that they “grieve differently.” Variables that enter into this phenomenon include individual past experiences, personal relationship with the deceased person, and individual temperament and coping abilities.

■ Recognize how the suicide has caused disorganization in family coping. Reassess interpersonal relationships in the context of the event. Discuss coping strategies that have been successful in times of stress in the past, and work to reestablish these strategies within the family. Identify new adaptive coping strategies that can be incorporated.