CHAPTER 2: THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

EXAM 1 STUDY GUIDE:

Terms: physiological ecology, population, community, ecosystem ecology, biosphere, macroclimate, maritime vs. continental climate, rain shadow, albedo.

1. Differentiate between a population, a community, an ecosystem, and the biosphere. What kinds of questions do ecologists ask at each level?

2. How does the global distribution of insolation affect temperature? Air circulation and upwellings? Rainfall? Be able to explain the processes. Likely that a number of questions will come from these topics.

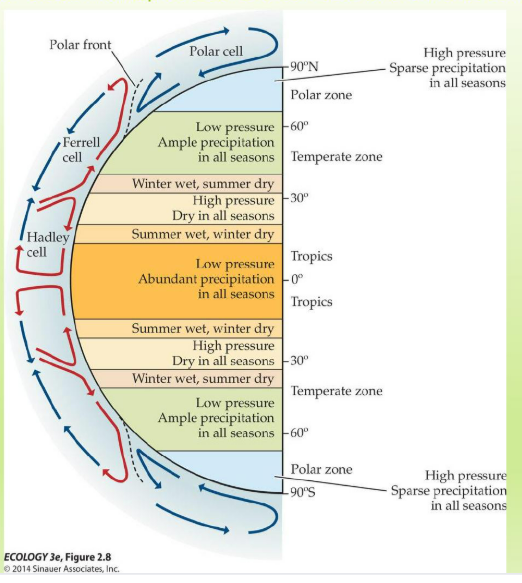

3. At what latitudes would you expect to see rain forests? Deserts? What do ocean circulation patterns have to do with climate?

4. How do mountains, large bodies of water, forests, and seasonal changes affect regional macroclimates?

5. Be able to explain why deserts, grasslands and temperate forests are limited to certain regions in the United States.

6. What is El Nino? How does it affect the climate of the Americas? How have long term variation in angle of inclination and the Earth’s orbit affected our climate? (Milankovitch cycles)

7. What is albedo? How does it impact temperature? How does deforestation impact albedo?

8. Explain the Milankovitch cycles and how they can affect global climate.

Chapter 2:

Understand cause and consequences of uneven heating of earth’s surface

Temperature, precipitation, winds

Understand regional factors that impact climate

mountains, currents, forests, maritime climate

Understand long-term climate variation

El Nino, orbit, sunspots

Why does climate vary?

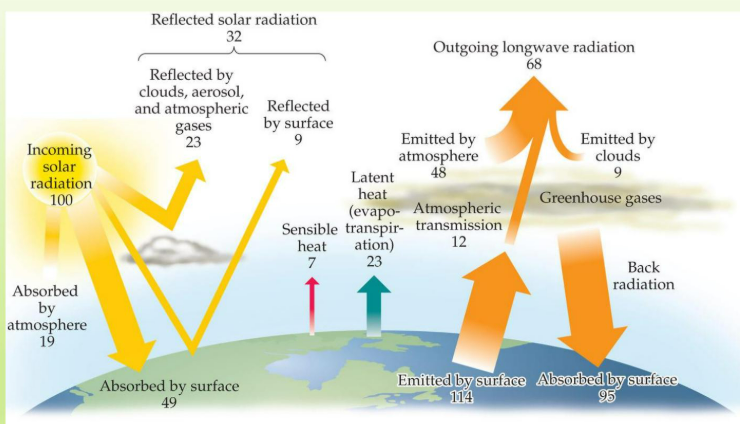

Earth’s Radiation Balance

Earth’s surface releases more energy than it receives

Evapotranspiration: (ex: reason you sweat)

Global Macroclimate:

INSOLATION(solar energy/ area) decreases towards poles because of greater depth of atmosphere, greater angle of incidence

Ex: Warm Equator Cool Poles

Average temperature drops, variation increases towards poles

Latitudinal Differences in Solar Radiation at Earth’s Surface lead to distinct climatic zones, impacting biodiversity and ecosystems as well as human activities across these regions.

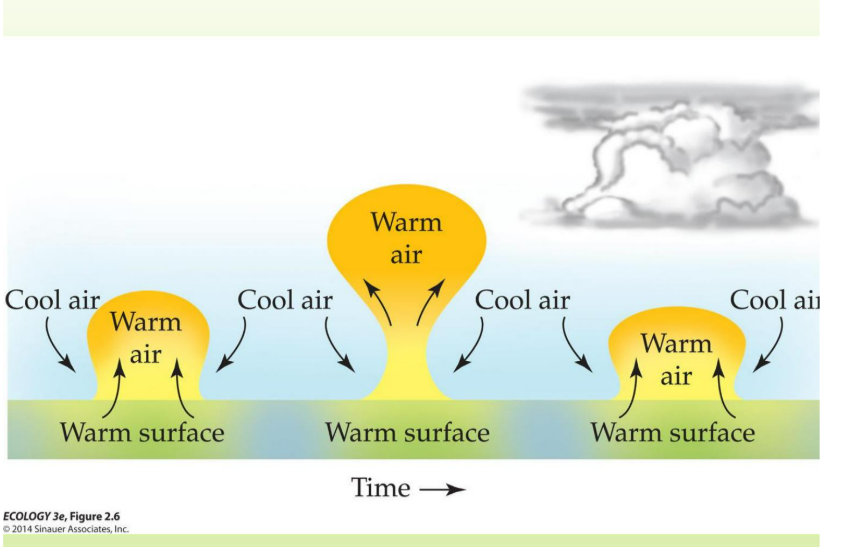

Surface heating and Uplift of Air (fig 2.6)

Way to understand: Warm air pushed up/ Cold air is pushing

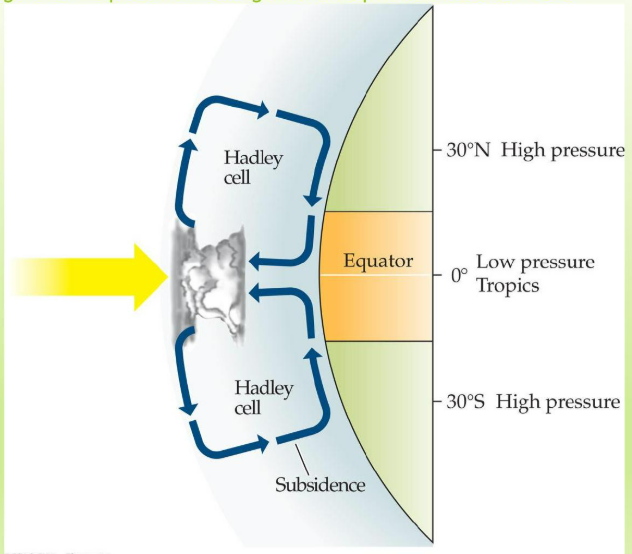

Equatorial Heating and Atmospheric Circulation Cells (fig 2.7)

Global Atmospheric Circulation Cells and Climate Zones

Influence on Global Wind Patterns

Coriolis Effect: This phenomenon results from the Earth's rotation, causing moving air and water to turn and twist rather than travel in straight lines, significantly impacting global wind patterns and ocean currents.

Regional Macroclimate

Currents and Deserts

Fig 2.16: Average Annual Terrestrial Precipitation

Fig 2.12: Upwelling of Coastal Waters

Ex: San Francisco Bay area. Nutrient rich region, and brings a lot of sea life/diversity into this environment

Fig 2.11: Global Ocean Currents

Ocean currents rotate clockwise in N-Hemisphere, so winds coming in off cool waters create deserts on western side of continents

This also affects the distribution of marine organisms

Rain Shadows

Review Fig 2.6: Surface Heating and Uplift of Air

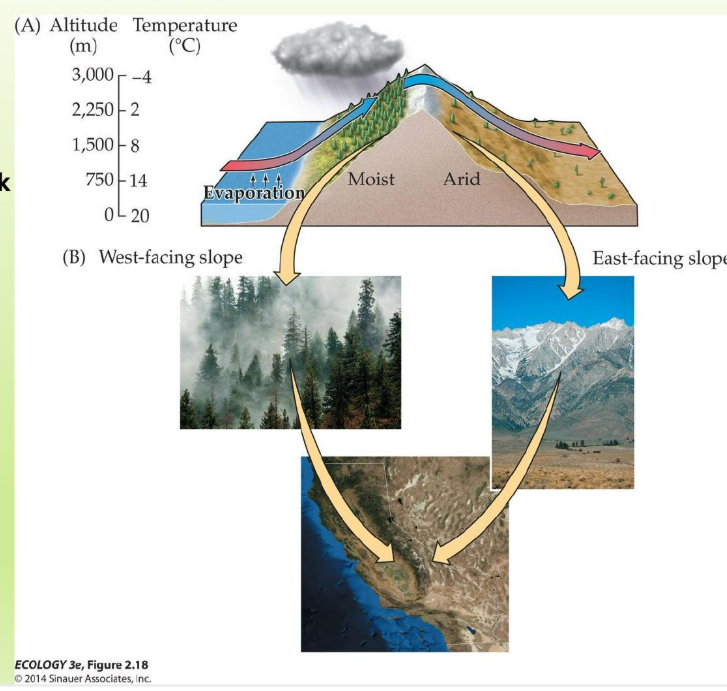

Fig 2.18: The Rain-Shadow Effect

Mountains block clouds, cause leeward rain shadows

Maritime Climates

Water has a higher specific heat capacity

Fig 2.17: Monthly Mean Temperatures in a Continental and Maritime Climate

An area within a continent is going to have wider temperature swings because the land heats up and cools down faster than water, leading to more extreme variations in climate.

Forests

Fig 2.19: The Effects of deforestation Illustrate the Influence of Vegetation on Climate

Forests cause a cooler wetter climate

Albedo: The reflectivity of Earth's surface, which is influenced by the type of vegetation present in forests.

Vegetated: areas tend to have lower albedo values, resulting in increased absorption of solar energy and consequently affecting local temperatures.

Deforested: areas typically exhibit higher albedo values, leading to greater reflectivity and a potential rise in local temperatures due to reduced solar energy absorption.

SUMMARY- US MACROCLIMATE:

Rain forest in NW- precipitation occurs in winter ( warm ocean air dumps moisture), few deciduous trees

Deciduous: trees are adapted to seasonal changes, shedding their leaves in autumn to conserve water during the colder months.

Deserts in SW (ocean air picks up moisture)

Rain shadow east of Rockies creates temperature grasslands (short to tall grass prairie as move eastward)

Eastern Seaboard has maritime climate

Longer Term Variation in Macroclimate

Most Frequent:

Axis of inclination changes seasonally (23 N in summer, 23 S in winter)

Fig 2.21 Wet and Dry Seasons and the ITCZ

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) shifts with the sun's position, leading to distinct wet and dry seasons in tropical regions.

Sun passes over equator twice a year

Temperature continents heat up and rain in summer

El Nino (fig 2.23)

El Nino is a longer term (9 months every 2-7 years) E—W oscillation, creating wet climate in the Western Americas and drought in ASIA

La Nina is the counterpart to El Nino, characterized by cooler ocean temperatures in the central Pacific, which often results in wetter conditions in Asia and drier conditions in the Western Americas.

Changes in orbit

Other long term climate factors

Sunspots

Maunder minimum

11 year Cycle

Fig 2.24 Long Term Record of Global Temperature

Earth’s temperature varies over longer time intervals due to changes in orbit, inclination of axis

Fig 2.25 The Most Recent Glaciation of the Northern Hemisphere

Ex: ‘Doggerland’: A land bridge that once connected Great Britain to continental Europe, significant for understanding prehistoric human migration patterns.

Least Frequent

Milankovitch Cycles: Periodic changes in Earth's axial tilt, eccentricity, and precession that influence long-term climate patterns, playing a crucial role in the timing of glacial and interglacial periods. This happens every 100,000 years, resulting in variations that can significantly impact global temperatures and sea levels.

Orientation of Celestial Bodies: The positioning and movements of stars and planets in relation to Earth, affecting navigation, seasonal changes, and the development of various cultural and scientific practices throughout history. This happens every 41,000 years, which significantly impacts climate and environmental conditions on Earth.